Lost works by Vincent van Gogh

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The events that befell the early paintings and drawings by Vincent van Gogh in the period prior to the posthumous recognition of Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890) as an innovative artist show how the appreciation of his legacy changed his reputation in a relatively short time.

A part of the work that remained with his family when he left the Netherlands must be considered lost, and the remaining early works of Vincent van Gogh tell an incomplete story. Van Gogh himself wrote that he had stored some 70 painted studies in the attic of his studio when he left The Hague, but only some 25 of these are now known.[1][2] Some of those involved in the early trade have been interviewed by journalists and art researchers, but the literature on Van Gogh relies and focuses largely on his known existing work.

To Breda

[edit]

The father of Vincent van Gogh, the Nuenen pastor Theo van Gogh, died unexpectedly on 26 March 1885. Vincent moved to Antwerp on November 27. In the following months his mother, Anna-Cornelia van Gogh-Carbentus, decided to move to a smaller home for her and her daughter Wil. They found an upper part of a house on the corner of the Nieuwe Ginnekenstraat and Wapenplein (nowadays Van Coothplein 33 A) in Breda and moved there on 30 March 1886 (coincidentally Vincent's 33rd birthday).[citation needed]

Vincent's mother had a part of the furniture, including Vincent's possessions, stored because the new house had insufficient space.[3] It ended up in a warehouse owned by a carpenter, Adrianus Schrauwen, living in the Ginnekenstraat. When the furniture and boxes were later retrieved, Vincent's sister Wil discovered traces of woodworm in the crates and it was decided to leave it with Schrauwen in the attic.[4]

"Rubbish" of Vincent

[edit]In the period from November 1885 until the end of February 1886, Vincent wrote from Antwerp to his brother Theo in Paris various letters about the upcoming move in March 1886 of his mother and sister. He wondered if he had to help with arrangements in Nuenen. Vincent went to Paris at the end of February 1886 and he did not help his family with packing. When the family moved, the things that Vincent had left behind when he went to Antwerp, including wood engravings and books, were stored in a carpenter's attic in Breda. The carpenter's name was Adrianus Schrauwen. In a letter from Arles to his sister Wil from June 1888 Vincent writes:[5]

- Speaking of rubbish... It is perhaps worth saving what is good among the rubbish which, as Theo says, is still in an attic somewhere in Breda. I dare not ask, however, and perhaps it is lost, so do not worry about it.

According to specialist researcher Jan Hulsker in his book Van Gogh door Van Gogh (1973) the word rubbish refers not to Vincent's own work, but to books and woodcuts, illustrations which he had taken from magazines and such. In a postscript of a letter in early August 1888, Vincent asks Wil to bring him some wood engravings and prints that had remained in Breda.[6]

Role of Schrauwen

[edit]This could mean that Vincent considered his work in the attic at Schrauwen lost. In any case, in 1888 Theo and Wil knew of belongings that had been left behind in Breda. In a letter from Vincent to Wil (end of October 1889) he says that Wil and her mother would move shortly thereafter to Leiden. The population register in Breda mentions that the move took place on November 2, 1889. On this basis, it is assumed that in the beginning of November 1889 his mother and Wil reclaimed their possessions from Schrauwen, but left Vincent's boxes because of the alleged woodworm.[4]

Stokvis writes in his Research about Vincent van Gogh in Brabant (Nasporingen omtrent Vincent van Gogh in Brabant, 1926) on page 27:

- At the request of the old Mrs Van Gogh one of the sisters Begemann (in Nuenen) had a part of what had been left behind in the studio, packed in boxes and sent to carpenter Schrauwen in Breda after the departure of the family.

Years later, Schrauwen considered himself the rightful owner of the boxes because nobody had ever picked them up, he broke them open, took the folders with drawings, sketches and watercolors, and used the wood for various other purposes.[4]

Role of Couvreur

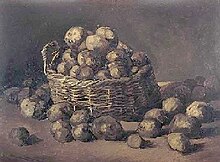

[edit]Seventeen years later, in 1903, Schrauwen invited a market merchant Mr. J.C. Couvreur to sell some belongings, such as a small can, a pot and other kitchen equipment. Couvreur offered 2.50 guilders and Schrauwen accepted on condition that he also take the rubbish which he had stored in his attic for so long. Couvreur agreed and stored the approximately sixty paintings, one hundred and fifty loose canvases, eighty pen drawings and between one hundred and two hundred chalk drawings in the basement of his house in the Stallingstraat in Breda.[4][7]

He spoke of this in an article in the newspaper De Telegraaf on 25 April 1938:

- So I had those things in the basement, higgledy-piggledy, my wife looked there every now and then, flipped through the drawings and saw many nude studies. She said to me: That I do not want to have in my house, it must go. I said: you can never know what those things may turn out to be worth, but my wife said: those things go out the door or I go out the door. In such a case, things go out the door. So I went into my basement one day, picked up all drawings that were somewhat offensive, put them in a big bag and when that bag was full, I brought it to the paper factory of Tilburg to be ground to paper; I've had a few dimes for it. [citation needed]

After clearing his basement of the bags with nude drawings, Couvreur wanted to get rid of the remaining pictures as well and he approached a Rotterdam paintings merchant, called De Winter, who thought it was worthless, according to Couvreur in an article on 18 February 1950 in the Breda newspaper De Stem. Couvreur also delivered some paintings to Frans Meeuwissen, the owner of the café at the corner of Ginnekenstraat and Stallingstraat, who sold them or gave them away to customers. If someone offered Couvreur a beer, he could have a Van Gogh.[citation needed]

Van Goghs for a dime

[edit]Couvreur was planning on selling the remaining canvases and drawings on the market, he tells in a Telegraaf newspaper article:

- I have stood on the market with a cart for thirty years. I pinned the drawings and paintings of Van Gogh on the cart and anyone could have one for ten cents. Sometimes I gave them to the children on the street to play with. One of those pieces I had to buy back later for seventy-five guilders. I was now gradually getting rid of the items in the basement.[citation needed]

According to his story one day on his way to the market in the Ginnekenstraat the tailor C. Mouwen approached him to buy some paintings. Couvreur sold him six canvases for ten cents each. Later in the day a maid of Mouwen came and asked if she could have another six for the same price.

- My wife says: now don't be silly, he does not do it for fun, those things are worth more that. You need to ask not one, but two dimes apiece. I said to the girl: thank Mr. Mouwen and tell him he can get six for two dimes apiece. The girl went away, came back and said that Mr. Mouwen would not go higher than 35 cents per piece. I quickly sold them for thirty-five cents per piece.[citation needed]

In a short time, the amounts went tenfold, and then again:

- Then one morning comes which I shall never forget. Coincidentally, I get a newspaper in my hands and I see that Van Gogh is a famous painter. Well, I thought, now I understand how that Mr. Mouwen could make me earn 25 cents on a painting! I spoke with him and we agreed that I would try to find the people to whom I had sold paintings for a dime and fifteen cents, and ask them to sell the pictures back. We have been busy with that for a while. For example, there was a farmer who had two pieces of me. I went to the man and said: can I have them back for a two and half guilders? And he gave them for 2.50 guilders. ... It was a strange story. To get them back I had to pay fifty, sixty, seventy guilders to the parents of the children to whom I had sold those paintings.[citation needed]

The majority of the retrieved works was bought by C. Mouwen, who loaned some fifty paintings for an exhibition with art dealer Oldenzeel in Rotterdam in January 1903 and sold 25 paintings at an auction on 3 May 1904, and an unknown number went to his cousin W. van Bakel, lecturer at the Royal Military Academy in Breda. Because the names of the buyers have not all been recorded, traces of early works by Van Gogh continued to get lost until the early 20th century.[citation needed]

Breda Museum's Lost and Found exhibition

[edit]Breda Museum hosted an exhibition called Vincent van Gogh: Lost and Found between November 2003 and February 2004. The show-piece of the exhibition was a painting Houses near the Hague, which the museum claimed had been authenticated by their experts as painted by Vincent on the basis of x-ray analysis. The painting had come from the so-called Marijnissen collection of Barend den Houter, a tax official at Breda. This collection had formerly been examined by experts in 1940 and declared unimportant, consisting of forgeries or work by little known contemporaries. However, Breda Museum said they had uncovered a connection between den Houter and Vincent's mother. The Van Gogh Museum said they were sceptical about the authenticity of the painting.[8][9][10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hulsker (1980) p. 54

- ^ "Letter 391: To Theo van Gogh. Hoogeveen, Friday, 28 September 1883". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 8.

I have more than 70 painted studies lying in The Hague ...

- ^ "Jo van Gogh-Bonger's Memoir of Vincent van Gogh". vggallery.com.

When in May his mother also left Nuenen, everything belonging to Vincent was packed in cases, left in the care of a carpenter in Breda and--forgotten! After several years the carpenter finally sold everything to a junk dealer.

- ^ a b c d Stockvis, Benno J. "Letter from Benno J. Stokvis to n/a Breda, 1926". WebExhibits.

- ^ "To Willemien van Gogh. Arles, between Saturday, 16 and Wednesday, 20 June 1888". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. note 9. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Sunday, 15 July 1888". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. note 12. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ Wilkie (2004) p. 247

- ^ "Alleged newly discovered van Gogh". Associated Press. 12 March 2003.

- ^ "Statement in response to questions raised by the exhibition 'Lost and Found' at the Breda's Museum". Van Gogh Museum. 18 November 2003.

- ^ Wilkie (2004) pp. 248-9

Literature

[edit]- Bram Huijser, Een kar vol Van Goghs en de handel daarin. In Kunstbeeld 1990, and Kunstkanaal.

- Ron Dirven en Kees Wouters (red.), Verloren vondsten. Breda's Museum, Breda (2003), a reconstruction of the history of early works by Van Gogh around Breda, with a chapter on the roots of the Hidde Nijland collection, which has formed the basis for the large collection of Van Goghs in the Dutch Kröller-Müller Museum.

- Benno Stokvis, Nasporingen omtrent Vincent van Gogh in Brabant, S.L. van Looy, Amsterdam (1926), covering Van Gogh in Brabant

- Mark Edo Tralbaut, Vincent van Gogh, Macmillan, Londen (1969)

- Hulsker, Jan. The Complete Van Gogh. Oxford: Phaidon, 1980. ISBN 0-7148-2028-8

- Wilkie, Ken. The Van Gogh File: The Myth and The Man. Souvenir Press 2004. ISBN 0 285 63691 X