Still life paintings by Vincent van Gogh (Paris)

This painting represents some of Van Gogh's early Paris still life, where he introduced brighter, contrasting color.

This is an example of Van Gogh's integration of brighter, contrasting colors and Impressionist brushstroke techniques.

Still life paintings by Vincent van Gogh (Paris) is the subject of many drawings, sketches and paintings by Vincent van Gogh in 1886 and 1887 after he moved to Montmartre in Paris from the Netherlands. While in Paris, Van Gogh transformed the subjects, color and techniques that he used in creating still life paintings.

He saw the work and met the founders and key artists of Impressionism, Pointillism and other movements and began incorporating what he learned into his work. Japanese art, ukiyo-e, and woodblock prints also influenced his approach to composition and painting.

There was a gradual change from the somber mood of his work in the Netherlands to a far more varied and expressive approach as he began introducing brighter color into his work. He painted many still life paintings of flowers, experimenting with color, light and techniques he learned from several different modern artists before moving on to other subjects.

By 1887, his work incorporated several elements of modern art as he began to approach his mature oeuvre. Excellent examples are the Pairs of Shoes paintings, where in the space of four paintings one can observe the difference between the first pair of boots made in 1886, similar to some of his earlier peasant paintings from Nuenen, to the painting made in 1887 that incorporates complementary, contrasting colors and use of light. Another example are the Blue Vases paintings made in 1887 that incorporate both color and technique improvements that result in uplifting, colorful paintings of flowers.

In the spring of 1887, Van Gogh left the city proper for a visit to Asnières with his friend Émile Bernard. While there his work was further transformed stylistically and through the use of bright, contrasting color and light. See his works from Asnières and Seine.

Background

[edit]Netherlands

[edit]From 1880 to 1885, Van Gogh began working as an artist in earnest. He was influenced not only by the great Dutch masters but also to a considerable extent by his cousin-in-law Anton Mauve a Dutch realist painter and a leading member of the Hague School.[1]

Van Gogh's palette consisted mainly of dark earth tones, particularly dark brown. His brother Theo, an art dealer, commented that his work was too somber to be marketable and encouraged him to explore modern art, particularly Impressionism for its bright, colorful paintings.[2]

-

A Girl in the Street, Two Coaches in the Background, 1882, Private collection (F13)

-

Still Life with Earthenware, Bottle and Clogs, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F63)

-

Head of a Peasant Woman with White Cap, 1885, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh (F140)

Modern art

[edit]In 1886, Van Gogh left the Netherlands and traveled to Paris to explore emerging artistic movements under the guidance and continued support of his brother Theo van Gogh, an art dealer.[1] Surprised that Vincent had come to Paris unannounced, and in opposition to their conversations about timing of his arrival, Vincent stayed in Theo's apartment on Rue Laval until a larger apartment could be acquired.[3] For four months, Van Gogh studied with Fernand Cormon, painting plaster casts, live nude models and props available at Cormon's studio. Cormon also encouraged open-air painting. There he met Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard, and Louis Anquetin.[4] Through Theo and artistic social circles he also met Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro,[5] Paul Signac, Georges Seurat,[6] and Paul Gauguin. Through the fellowship with these men, he was introduced to Impressionists, Symbolists, Pointillists, and Japanese art, Ukiyo-e, and woodcut prints.[1] In spite of his unusual demeanor, disheveled clothes and often time frightening manner, Paris was the one place where Van Gogh developed friendships with other artists. So much so that when Toulouse-Lautrec heard disparaging remarks against Van Gogh, he challenged the man to a duel.[7] Seeing and trading artwork with the Parisian avant-garde artists, Van Gogh understood what Theo had been trying to tell him for years about modern art.[8] He was able to experiment with each of the movements to develop his own style, becoming what some say is "one of the most important artists in modern art."[4]

Romanticism

[edit]Romanticism was an art and literature movement formed by people looking to escape the drab world. Its characteristics are paintings of "exotic lands" with grandiose feeling and intense color.[9] Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli developed a highly individual Romantic style of painting with richly colored, dappled, and textured painting and glazed surfaces.[10] Monticelli was a French painter of the generation preceding the Impressionists who was friends with Narcisse Diaz, a member of the Barbizon school, and the two often painted together in the Fontainebleau Forest. Vincent van Gogh, greatly admired his work after seeing it in Paris when he arrived there in 1886.[11] Van Gogh was influenced by the richness that he perceived in Monticelli's work.[12] In 1890, Van Gogh and his brother Theo were instrumental in publishing the first book about Monticelli.[13][14]

-

Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli, Still life with Sardines and Sea Urchins, 1880–1882, Dallas Museum of Art

Impressionism

[edit]The Impressionism movement was a change from traditional artistic techniques. With Impressionism the intention was to depict colors and images the way they are seen, not the way that artists were taught to paint them. Aspects of Impressionism include using gleaming spots of light, color in shadows, colors straight from the tube in dots or dashes, and dissolving firm outlines.[15]

-

Édouard Manet, Carnations and Clematis in a Crystal Vase, 1883, Musée d'Orsay

-

Edgar Degas, Two Ironing Women, 1884, Musée d'Orsay

-

Claude Monet, Still-Life with Anemones, 1885

Neo-Impressionism

[edit]Van Gogh was influenced by Impressionists Edgar Degas and Claude Monet, but even more so by Neo-Impressionist Georges Seurat, partly because of the use of dots of contrasting colors to intensify the image, a technique called Pointillism. Van Gogh likened painting with constructing small, thoughtfully placed dashes of color to writing "words in a speech or a letter".[16]

-

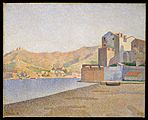

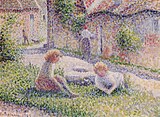

Camille Pissarro, Shepherdess with Returning Sheep, 1886, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art. One of Pissarro's first Pointillist paintings.

-

Camille Pissarro, Children on a Farm, 1887

Cloisonnism

[edit]Cloisonnism is a style of Post-Impressionist painting with bold and flat forms separated by dark contours. The term was coined by critic Edouard Dujardin on occasion of the Salon des Indépendants, in March 1888.[17] Artists Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, Paul Gauguin, Paul Sérusier, and others started painting in this style in the late 19th century. The name evokes the technique of cloisonné, where wires (cloisons or "compartments") are soldered to the body of the piece, filled with powdered glass, and then fired. Many of the same painters also described their works as Synthetism a closely related movement.[18]

-

Émile Bernard, Pardon at Pont-Aven, 1888

-

Émile Bernard, Portrait of a Boy in Hat, 1889, Musée d'Art et d'Industrie de Roubaix.

Post-Impressionism

[edit]Post-Impressionism is the term coined by the British artist and art critic Roger Fry in 1910 to describe the development of French art since Manet. Fry used the term when he organized the 1910 exhibition Manet and Post-Impressionism. Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations: they continued using vivid colours, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, but they were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, to distort form for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary colour.[19]

-

Paul Cézanne, Still life with Soup Tureen, 1884, Musée d'Orsay

-

Paul Gauguin, Seaside II, 1887

-

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh, 1887, Van Gogh Museum

Japanese ukiyo-e

[edit]Characteristic features of Ukiyo-e woodprints include their ordinary subject matter, the distinctive cropping of their compositions, bold and assertive outlines, absent or unusual perspective, flat regions of uniform colour, uniform lighting, absence of chiaroscuro, and their emphasis on decorative patterns.[20] One or more of these features can be found in numbers of Vincent's paintings from his Antwerp period onwards.[21][22] Van Gogh wrote, "If we study Japanese art, we see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophical and intelligent, who spends his time… studying a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him to draw every plant, and then the seasons, the wide aspects of the countryside, then animals, then the human figure… isn't it almost a true religion which these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves are flowers. And you cannot study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much gayer and happier."[23]

-

Utagawa Hiroshige, The Intertwined Catalpa Trees at Azuma Grove, c. 1856–58, Japanese Ukiyo-e, woodcut print

-

Utagawa Hiroshige, Evening Shower at Atake and the Great Bridge

-

Japonaiserie: Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), by Vincent van Gogh, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F372)

Color theory and technique

[edit]

One of the most transformational elements of Van Gogh's work during his period in Paris was his use of color. Van Gogh used complementary, contrasting colors to bring an intensity to his work. Two complementary colors of the same degree of vividness and brightness placed next to one another produce an intense reaction, called the "law of simultaneous contrast."[24]

From his days in the Netherlands Van Gogh became familiar with Delacroix's color theory and was fascinated by color.[25] While in Nuenen Van Gogh became familiar with Michel Eugène Chevreul's laws in weaving to maximize the intensity of colors through their contrast to adjacent colors.[26]

In Paris, Van Gogh eagerly studied Seurat's use of complementary colors. Excited to try out complementary studies, Van Gogh would divide a large canvas into several rectangular sections, trying out "all the colors of the rainbow."[25] There he was also exposed through his brother Theo to Adolphe Monticelli's still life work with flowers, which he admired. He saw Monticelli's use of color as an expansion of Delacroix's theories of color and contrast. He also admired the effect Monticelli created by heavy application of paint.[10]

In the still life series, particularly of flowers, Van Gogh experimented with color relationship, such as complementary, contrasting colors which are colors across from one another on the color wheel. A second color relationship, harmonious colors are colors adjacent to one another on the color wheel. He also used the trio of colors, where the relationship on the color wheel forms a triangle.

Balls of yarn

[edit]To help him choose colors for his studies, Van Gogh collected strands of different shades of yarn to experiment with color combinations. He rolled selected strands together into balls in combinations matching specific paintings, such as the yellow and ocher combinations found in Still Life with Quince Pears and Lemons (F383). The box and his sample balls of yarn have survived and are held by the Van Gogh Museum.[27]

Still life

[edit]

Soon after Van Gogh arrived in Paris, he began painting still lifes with the goal of experimenting with contrasting colors. He wrote to a friend in England that his goal was to create "intense coloration, not gray harmony."[28]

His started with still lifes of flowers. At first his still lifes maintained the subdued tones that he used in the Netherlands. The more he became immersed in his painting, he continually added brighter colors to his work until he was using colors directly from the tube. Then he moved on to other subjects from everyday life that reflect his use of vivid colors and a free brushstroke.[29]

Van Gogh courted Agostina Segatori, the owner of the Café du Tambourin on the boulevard de Clichy, for a period of time and gave her paintings of flowers, "which would last for ever".[30]

The energy that Van Gogh put into his Still Life paintings is representative of his habit for "working systematically, concentrating on a theme until he had exhausted it."[31]

Flowers

[edit]Flowers were the subject of many of Van Gogh's paintings in Paris, due in great part to his regard for flowers. Knowing Van Gogh's interest in making still life paintings of flowers, friends and acquaintances in Paris sent bouquets of flowers weekly for his paintings.[32] He also purchased inexpensive bouquets himself, choosing flowers in a variety of types and colors for his paintings.[33] Many of his still life paintings of flowers reflect a sense of overabundance of European still lifes, where blossoms fill the canvas, blooms spill out of the vase or stems of flowers teeter on the edge of the vase.[34]

Van Gogh carefully studied the art of floral arranging, the works of Dutch masters, Japanese woodcut prints and Impressionist still life arrangements to master his paintings of flowers.[35] Expressing his enthusiasm for the subject and the number of paintings he completed in Paris, Van Gogh wrote to his sister Wil, "I painted almost nothing but flowers so I could get used to colors other than grey - pink, soft or bright green, light blue, violet, yellow, glorious red."[36] His expertise in color, composition, texture and placement may have made an impression on Constance Spry, a noted floral arranger who created guidelines for flower arranging as an art form. She learned a great deal about "structure, style, form, balance, harmony and rhythm" from studying the paintings by great masters of flowers.[35]

The longer he was in Paris, the more he had an Asian aesthetic for flowers. As he said to his brother Theo: "You will see that by making a habit of looking at Japanese pictures you will come to love to make up bouquets and do things with flowers all the more."[32]

Van Gogh had an agreement with the Agostina Segatori proprietress of Café du Tambourin, an establishment that catered to Montmartre artists, for meals in exchange for a few paintings each week. Soon the walls of the café were full of floral still life paintings.[37]

Carnations

[edit]

-

Vase with Carnations, 1886, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands (F220)

-

Vase with White and Red Carnations, 1886, Private collection (F236)

-

Vase with Carnations, 1886, Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan (F243)

-

Vase with Carnations and Zinnias, 1886, Private collection (F259)

-

Vase with Red and White Carnation on a Yellow Background, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F327)

-

Vase of carnations and other flowers, 1886, Private collection (F596)

Chrysanthemums

[edit]Chrysanthemums, often depicted in Japanese woodcut prints, were painted by Impressionists primarily in floral arrangements. The most desired chrysanthemum was an autumn-blooming variety from Japan.[38]

-

Ginger Jar Filled with Chrysanthemums, 1885, Private Collection (F198)

-

Bowl with Chrysanthemums, 1886, Private Collection (F217)

-

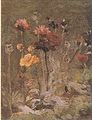

Chrysanthemums and Wild Flowers in a Vase, 1887, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (F588)

Fritillaries

[edit]Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase (F213) reflects the influences of Neo-Impressionist Paul Signac. The background is painted with Pointillist brushwork. The painting was made with complementary, contrasting colors of blue and orange. Van Gogh was not a purist; he varied the shades of contrasting colors and chose subjects that he enjoyed, such as painting still lifes. Fritillary is a bulb that flowers in the spring with between three and ten flowers for each bulb. Imperial fritillaries, with an orange-red flower, were grown in French and Dutch gardens at the end of the 19th century.[30]

-

Fritillaries, 1886, Location unknown (F214)

-

Fritillaries in a Copper Vase, 1887, Musée d'Orsay, Paris (F213)

Gladiola

[edit]

The Gladiolus, plural Gladioli, was one of Van Gogh's favorite flower. He especially enjoyed how they opened up like a fan after having been placed in a vase.[39] Because of their height, Van Gogh liked to use Gladioli to create triangular-structured compositions,[35] such as Vase with Gladioli and Carnation (F237) or an inverted triangle as in Vase with Gladioli and China Asters (F248a).

-

Vase with Red Gladioli, 1886, Private collection (F248)

-

Vase with Gladioli and China Asters, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F248a)

-

Vase with Red Gladioli, 1886, Musée Jenisch, Vevey, Switzerland (F248b)

-

Vase with Gladioli and Carnations, 1886, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (F237)

-

Vase with Gladioli and Carnations, 1886, Private collection (F242)

Poppies

[edit]Vase with Red Poppies (F279) is another illustration of how Van Gogh used red and green primary, complementary colors to make both colors appear more intense, set before a blue background. He paints pink in the unopened buds and sienna in the table.[40]

-

Vase with Red Poppies, 1886, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford (F279)

-

Poppy Flowers also Vase with Viscaria, 1886, Stolen August 2010 from Mohammed Mahmoud Khalil palace, Cairo (F324a)

-

Vase with Cornflowers and Poppies, 1887, Private collection (F324)

Roses

[edit]Van Gogh's paintings of rose, or any flowers, are evocative of his quote, "Ah, what portraits could be made from nature with photography and painting."[41]

-

Glass with Roses, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F218)

-

Bowl with Peonies and Roses, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F249)

-

White Vase with Roses and Other Flowers, 1886, Private collection (F258)

-

Still life with meadow flowers and roses, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Sunflowers

[edit]Two Cut Sunflowers (F375) is one of a sequence of four paintings that Van Gogh made in the summer of 1887. The first (Van Gogh Museum, F377) was a preparatory sketch. Paul Gauguin had the second and third Two Cut Sunflower paintings (F375, F376) and hung them proudly in his Paris apartment above his bed. In the mid-1890s he sold them to fund his trip to the South Seas. The image of the four sunflowers was made on a large canvas.[42]

-

Two Cut Sunflowers, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F377)

-

Two Cut Sunflowers, 1887, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (F375)

-

Two Cut Sunflowers, 1887, Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland (F376)

-

Four Sunflowers Gone to Seed, 1887, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F452)

Zinnias

[edit]Vase with Zinnias and Geraniums (F241) reflects the influence of Adolphe Monticelli (1824–1886) in its vivid color and impasto paint. Van Gogh admired, and later collected, Monticelli's work.[43] Van Gogh had been introduced by his brother Theo to Monticelli's still life work with flowers in Paris. He admired Monticelli's use of color as an expansion of Delacroix's theories of color and contrast. Secondly he admired the effect Monticelli created by heavy application of paint called "impasto". It was partially Monticelli, from Marseilles, who inspired Van Gogh's southerly move to Provence in 1888. He felt such kinship for the man, and desire to emulate his style, that he wrote in a letter to his sister Wil that he felt as if he were "Monticelli's son or his brother."[10] The first owner in the provenance of this painting is "C.M. van Gogh Gallery, Amsterdam, the Netherlands", which was owned by Van Gogh's uncle and an art dealer, Cornelius Marinus van Gogh (1824–1908).[43]

Bowl with Zinnias and Other Flowers (F251), painted within days of Vase with Zinnias and Geraniums (F241), is evidence of Van Gogh's transition to a lighter color palette. Picking up elements of Impressionism Van Gogh painted with a more vigorous brushstroke, with thick application of paint, called "impasto" which created a three-dimensional relief.[32][44]

-

Vase with Zinnias and Geraniums, 1886, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada (F241)

-

Bowl with Zinnias and Other Flowers also Vase with Zinnias and Other Flowers, 1886, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada (F251)

-

Vase with Zinnias, 1886, Kreeger Museum, Washington D.C. (F252)

Other flowers

[edit]Unable to pay for models to pose for portraits, Van Gogh threw himself heartily into painting still lifes of flowers, "red poppies, blue corn flowers and myosotis, white and red roses, yellow chrysanthemums."[45]

Vase with Autumn Asters (F234) is one example of the many still lifes that Van Gogh painted after he arrived in Paris. As he said to a friend, he wished for his paintings to take on intense colors, rather than the grey tones.[28] In this arrangement Van Gogh plays with harmonizing colors: rose, pink, red and brown.[46]

Basket of pansies (F244) is an example of Van Gogh's experimentation with contrasting colors. In this case the contrasting pair are purple and yellow.[47] He also used the contrasting red in the tambourine and green in the background for the painting, also known as Tambourine with Pansies. Van Gogh found pansies an example of natural color theory.[33]

Vase with Hollyhocks (F235) was painted in the summer in contrasting shades of red and green. Van Gogh believed that he could express the season of the year by the colors that he used in his work. He experimented in this painting with creating an image that was nearly one-dimensional. The decorative jug used in this painting also appears in Van Gogh's Vase with Autumn Asters (F234).[33] Hollyhocks, native to China and Japan, were favored by Impressionists "for their spire-like growth, deeply-lobed green leaves and their satiny, cup-shaped flowers that hug the upper flower stem."[38]

-

Still Life with a Bouquet of Daisies, 1886, Philadelphia Museum of Art (F197)

-

Glass with Hellebores, 1886, Private collection (F199)

-

Vase with Autumn Asters also Vase with Asters and Phlox, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F234)

-

Vase with Hollyhocks, 1886, Kunsthaus Zürich (F235)

-

Vase with Myosotis and Peonies, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F243a)

-

Basket of Pansies on a Small Table, (Tambourine with Pansies), 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F244)

-

Vase of white carnations and roses and bottle, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F246)

-

Vase with cornflowers and poppies, peonies and chrysanthemums, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F278)

-

Vase with Asters, Salvia and Other Flowers, 1886, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague, Netherlands(F286)

-

Lilacs, 1887, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (286b)

-

Still Life with Scabiosa and Ranunculus, 1886, Private collection (F666)

Blue vase

[edit]

Vase with Daisies and Anemones (F323), also known as Flowers in a Blue Vase, was painted late in Van Gogh's stay in Paris. The vase holds a lively selection of daisies and anemones made with a range of colors. Dark red-brown is enlivened by shades of yellow, pink and white. He particularly works with the various shades of yellow, likely having selected colors for the combinations of color and shades that he wanted to portray. The vase is painted in a contrasting shade of blue. Techniques of Impressionism and Divisionism are reflected in his brushstrokes of the background, having used broken strokes and dots of color.[48]

-

Vase with Lilacs, Daisies and Anemones, 1887, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire (Geneva) (F322)

-

Flowers in a Blue Vase, 1887, Private collection (no F#, Add20)

Plants

[edit]Van Gogh preferred to select items from daily life to portray in his still life paintings. With Flowerpot with Chives (F337) Van Gogh used a thin brush to carefully create this painting of a pot of chives. Contrasting colors of red and orange against green are used in this work. The background is a pattern that Van Gogh used in other works,[49] such as Still life with Carafe and Lemons (F340).[50] From the time this painting was made in 1887 and forward, Van Gogh used colorful backgrounds for his still lifes and portraits.[49]

-

Geranium in a Flowerpot, 1886, Private collection (F201)

-

Coleus Plant in a Flowerpot, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F281)

-

Cineraria in a Flowerpot, 1886, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands (F282)

-

Flowerpot with Chives, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F337)

Bulbs

[edit]-

Still Life with a Basket of Crocuses, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F334)

-

Basket of Sprouting Bulbs, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F336)

Books

[edit]Still Life with French Novels and a Rose is a painting with a number of novels with bindings of contrasting colors: green against pink and red. The books are meant to represent seven Parisian novels Van Gogh owned,[51] that Van Gogh described as "a great source of light", regardless of the somber literature they contain. The dashes of lemon, pink, orange and green seem to bring life to the books, like the blossoming flower that[52] also adds a feeling that the paintings is made for a woman. In 1888 Van Gogh gave this painting and another to his sister, Wil for her birthday. The other painting was made in Arles and is titled Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book (F393).[51]

Still Life with Books (F335) was painted by Van Gogh on a lid of a Japanese tea box. The books are Naturalist novels: "Braves Gens" by Jean Richepin, "Au Bonheur Des Dames" by Émile Zola and "La Fille Elisa" by Edmond de Goncourt. Van Gogh, an avid reader, was particularly interested by French Naturalists. To his sister Wil, he once wrote "they paint life as we ourselves feel it, thereby fulfilling the need we have for people to tell us the truth."[53]

-

Still Life with Three Books, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F335)

-

Still Life with Piles of French Novels and a Glass with a Rose (Romans Parisiens), 1887, Private Collection, Switzerland (F359)

-

Still Life with Plaster Statuette, a Rose and Two Novels, 1887, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F360)

Pair of shoes

[edit]Van Gogh made Shoes (F255) from a pair of boots he purchased at a flea market. He wore the boots on an extended rainy walk to create the effect he wished for this painting, which may have been a tribute to the working man. The Van Gogh Museum speculates that they may also be symbolic for Van Gogh of his "difficult passage through life."[54] Of his walking through mud to make the shoes look more worn and dirty, Van Gogh was known to say "Dirty shoes and roses can both be good in the same way."[55]

Van Gogh's friend and fellow artist, John Russell, received Van Gogh's Three Pairs of Shoes (F332) in 1886. Russell had painted a portrait of Van Gogh that he dearly loved. In exchange for the portrait he had given Van Gogh, Russell selected Three Pairs of Shoes and a lithograph copy of Worn Out (Eternity's Gate) (F997) that Van Gogh made in 1882. Russell selected these works at a time when Van Gogh had begun to make more colorful work. Russell's selections indicate that he understood who Van Gogh was and the messages about the peasant or working man that he wished to convey through his work.[56]

-

Shoes, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F255)

-

A Pair of Shoes, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F331)

-

Three Pairs of Shoes, 1886, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge (F332)

-

A Pair of Boots, 1887, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland (F333)

Food and drink

[edit]

Glass of Absinthe and a Carafe (F339) was made by Van Gogh in a café. On the table sits a glass of absinthe, its green-yellow liquid lighter for window's sunlight and in contrast to the brown background. The painting catches a moment in the café from a patron's perspective, with a view of pedestrians walking on the street. Absinthe was popular to Van Gogh and other artists both as a drink, although toxic and in some cases deadly, and because of its unique color, it was also favored as a subject for paintings.[57]

Absinthe may have significantly contributed to Van Gogh's poor health. When he lived in Paris, absinthe was a popular drink among artists.[58] Paul Signac commented that Van Gogh drank steadily drinks of brandy following drinks of absinthe.[59] By the time Van Gogh left Paris he was in very poor health and known to say to a friend that drinking and smoking left him "seriously sick at heart and in body and nearly an alcoholic."[58] According to author Doris Lanier, author of "Absinthe the Cocaine of the Nineteenth Century": Many of Van Gogh's symptoms following his arrival in Paris are indicative of absinthe poisoning: stomach and nervous system problems, hallucinations and convulsions.[59]

-

Still Life with Apple, Meat, and Bread Rolls, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F219)

-

Still Life with Meat, Vegetables and Pottery, 1886, Private collection (F1670)

-

Still Life with Red Cabbages and Garlic, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F374)

-

Still life with bottle, two glasses, cheese and bread, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F253)

Fish or seafood

[edit]

Anecdotally, one cold Parisian day Van Gogh, dressed more like a cattle drover than an urban artist, peddled a painting of pink shrimp on pink paper to a shopkeeper who sold old ironworks and inexpensive oil paintings. Out of charity, the man gave the hungry Van Gogh five francs (less than a dollar). Out on the street, Van Gogh saw a prostitute who had recently escaped from Prison Saint-Lazare. With thoughts of the novel about a prostitute, "La Fille Elisa" by Edmond de Goncourt, Van Gogh gave her the five francs and quickly moved on his way.[60] The novel appears in Van Gogh's Still Life with Books (F335).[53]

-

Still Life with Bloaters also Smoked Herrings, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F203)

-

Still Life with Bloaters also Still Life: The Saurs Herrings, 1886, Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland (F283)

-

Still Life with Two Herrings, a Cloth and a Glass, 1886, Private collection (F1671)

-

Still Life with Bloaters and Garlic, 1887, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo (F283b)

Assorted fruit

[edit]In Van Gogh's first months in Paris, he stayed in his brother Theo's small apartment on Rue Laval. Vincent's behavior could be disruptive and unnerving to Theo and others. A friend of Theo's wrote of Vincent, "The man hasn't the slightest notion of social conditions. He is always quarreling with everybody. Consequently Theo has a lot of problem getting along with him." As means of calming himself, Vincent painted fall fruit in the autumn of 1886, which he imbues with seemingly "supernatural vitality and beauty." Multi-colored, contrasting colored brushstrokes radiate in a circle from the fruit with an "aura of electrical radiance."[61]

Van Gogh and Monet

Still Life with Apples, Pears, Lemons and Grapes (F382) was Van Gogh's opportunity to explore Blanc's recommendation about combining colors: "If one brings together sulfur (yellow) and garnet (dark red), which is its exact opposite, being equidistant from nasturtium (orange) and campanula (blue-mauve), the garnet and sulfur will excite one another, because they are each others' complementaries." In the background, Van Gogh used short brushstrokes of light blue and pink, giving the impression that the fruit is sitting in a basket. Van Gogh may have seen Claude Monet's Still Life with Apples and Grapes in Paris, but while the subject matter is roughly the same, the composition is not. Monet paints the fruit on a diagonally placed table to "anchor his composition in space."[62] Having removed any form of distraction, such as a table or background,[61] Van Gogh placed each piece of fruit by itself, creating a "semi-abstract, decorative effect."[62]

Still Life with Quinces and Lemons (F383) is a study in yellow. The painting, and even the frame, are in shades of yellow, ocher and brown. The painting also has highlights in pink, red, green and blue. A fine example of an Impressionist painting, Van Gogh dedicated the painting to his brother Theo for his guidance and introduction to modern art.[27] Over the yellow frame, Van Gogh painted criss-cross marks, evocative of Japanese calligraphy.[63] Adding a painted frame to a work of art was not unusual for painters of this time; Georges Seurat and Paul Signac also painted their frames. What is unusual is that the painted frame remained with the painting. In most cases the original frames were replaced over the years to suit its owner's taste.[27]

-

Still Life with Quinces, Lemons, Pears and Grapes, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F383)

-

Still Life with Quince Pears, 1887, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden, Germany (F602)

-

Still Life with Grapes, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F603)

Apples

[edit]The Netherlands (1885) to Paris (1887–88)

Basket of Apples (F99) was made in 1885 when Van Gogh experimented with Delacroix's color theory. To his brother Theo, Van Gogh wrote: "There is a certain pure bright red for the apples, then some greenish things. Now there are one or two apples in another color, in a kind of pink – to improve the whole. The pink is the broken color, created by mixing the first red and green mentioned. This is why there is a connection between the colors. Then I painted a second contrast, in the back- and foreground. One was given a neutral color by "breaking" blue with orange; the other the same neutral color, only this time changed by adding a little yellow."[64]

-

Still Life with Basket of Apples (to Lucien Pissarro), 1887, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F378)

-

Still Life with Basket of Apples, 1887–88, Saint Louis Art Museum, St Louis, Missouri (F379)

Lemons

[edit]Still Life with Lemons on a Plate (F338) is one of the paintings that Enrica Crispino, author of "Van Gogh" uses to illustrate Van Gogh's progression in the use of light and movement from colors darkened with black to "pure color".[65]

Van Gogh made Still life with Carafe and Lemons (F340) quickly, with a very thin layer of paint that does not completely obscure the canvas. The carafe of water catches the reflection of the papered background. Complementary colors are used well in the painting, such as yellow lemons against its purple shadow. The green in the foreground contrasts with the red in the background. Van Gogh signed this still life, indicating that he was pleased with the result.[50]

-

Still Life with Lemons on a Plate, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F338)

-

Still Life with Decanter and Lemons on a Plate, 1887, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (F340)

How Van Gogh integrated modern art concepts

[edit]Impressionism

[edit]Van Gogh's work in still life reflects his emergence as an important practitioner of modern art, particularly integrating techniques of Impressionism. The table identifies key Impressionist techniques and examples of how Van Gogh used them in this series of still life paintings.

| Impressionist technique | Examples in Van Gogh's work |

|---|---|

| Short, thick strokes of paint are used to quickly capture the essence of the subject, rather than its details. The paint is often applied impasto. Wet paint is placed into wet paint without waiting for successive applications to dry, producing softer edges and an intermingling of colour. | Van Gogh integrated Pointillism techniques in Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase (F213).[30] Vase with Zinnias and Geraniums (F241) is an example of impasto application of paint.[44] |

| Colors are applied side by side with as little mixing as possible, creating a vibrant surface. The optical mixing of colours occurs in the eye of the viewer. | Still life with Carafe and Lemons (F340) is an example of how Van Gogh used complementary colors, side-by-side, such as yellow lemons against its purple shadow.[50] |

| Grays and dark tones are produced by mixing complementary colours. In pure Impressionism the use of black paint is avoided. | In making Vase with Autumn Asters (F234) Van Gogh began to use more intense colors, rather than somber grey tones of his early work.[28] |

| The play of natural light is emphasized. Close attention is paid to the reflection of colors from object to object. | In Still Life with Glass of Absinthe and a Carafe (F339) Van Gogh paints a glass of absinthe that is made lighter by sunlight from the cafe window.[57] |

Color relationships

[edit]Van Gogh experimented with each of the three color relationships:

| Color relationship | Examples in Van Gogh's work |

|---|---|

| Complementary, contrasting colors - colors across from one another on the color wheel | Two Cut Sunflowers (F375) is painted with the contrasting pair blue and yellow.[42] Vase of Peonies, 1886, Private collection (F666a) is an example of green against pink. |

| Harmonious colors - adjacent colors on the color wheel | In Vase with Autumn Asters (F234) experiments with harmonizing colors: rose, pink and red.[46] Still Life with Scabiosa and Ranunculus, 1886, Private collection (F666) also has pink and red flowers and the background has a set of harmonious green-brown shades. |

| Trio of colors - colors that form a triangle on the color wheel | Vase with Red Poppies (F279) is another illustration of how Van Gogh the trio of red, green and blue for a visually interesting combination of colors.[40] |

Light

[edit]Van Gogh experimented with use of light over his ten-year painting career. A trio of still lifes shows his developing style for managing light. At first he placed light subjects against a background, as in Still Life with Four Stone Bottles, Flask and White Cup (1884) Then he realized the effectiveness of using "pure colors, such as in Still Life with Lemons on a plate (1887) and even more so in Still Life: Drawing Board, Pipe, Onions and Sealing-Wax (1889)."[65]

-

Still Life with Four Stone Bottles, Flask and White Cup, 1884, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F50)

-

Still Life with Lemons on a plate, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F338)

-

Still Life: Drawing Board, Pipe, Onions and Sealing-Wax, January 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F604)

Later in 1887

[edit]

After he made most of the still life paintings, Van Gogh left the city in April 1887 for the tranquil Parisian suburb called Asnières[66] and to paint with his friends and Asnières residents Paul Signac and Émile Bernard.[67] Asnières is located beyond the city fortifications, along the banks of the Seine and the island of Grand Jatte. There he experimented with an even lighter, more colorful palette than used in his early Montmartre, Still Life and Dutch paintings[68] and more fully defined his unique brushstroke: one that was rapid with thickly painted strokes laid closely together.[69]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]For books, also see the bibliography using the author's last name and, if indicated, the year the book was published.

- ^ a b c Wallace pp. 40, 69-70.

- ^ Tralbaut pp.123-160

- ^ Beaujean, 28

- ^ a b Beaujean, 27-28

- ^ Beaujean, 38

- ^ Beaujean, 31-32

- ^ Wallace, 40, 50-51

- ^ Wallace, 42

- ^ Munro, 216-217

- ^ a b c Silverman, 438

- ^ Van Gogh and Monticelli Exhibition Retrieved 24 May 2011

- ^ 1888 24 April, Letter to Theo

- ^ Turner, 314.

- ^ Bio Kunstmuseum Basel Retrieved 5 June 2011

- ^ Beaujean, 30

- ^ Beaujean, 31

- ^ Dujardin, Édouard: Aux XX et aux Indépendants: le Cloisonismé (sic!), Revue indépendante, Paris, March 1888, pp. 487-492

- ^ Hamilton, 105-106

- ^ Hamilton, 228-231

- ^ "Japonisme". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "The Japanese Print Collection". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "More Japan". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Fell (1997), 79

- ^ Fell (2005) p. 64

- ^ a b Wallace pp. 39, 75

- ^ Silverman, p. 140

- ^ a b c "Still Life with Quinces and Lemons". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Vase with Autumn Asters, 1886". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Still Lifes as Color Studies". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase". Works in Focus. Musee d'Orsay. 2006. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ Thomson, 46

- ^ a b c Mancoff, p. 32

- ^ a b c Mancoff, p. 29

- ^ Ross, 56.

- ^ a b c Fell (2001), 136

- ^ Mancoff, p. 26, 29

- ^ Fell (2005), 80

- ^ a b Fell (1997), 125.

- ^ Fell (2005), 136

- ^ a b Mancoff, p. 26.

- ^ Fell (1997), 44

- ^ a b "Sunflowers". Collection Database. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Vase with Zinnias and Geraniums". Collections. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Vase with Zinnias and Other Flowers". Collections. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Leeuw, PP342

- ^ a b Mancoff p. 37

- ^ "Basket of pansies, 1886". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ Mancoff p. 34

- ^ a b "Flowerpot with Chives, 1887". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Still life with Carafe and Lemons". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Wilhelmina van Gogh. Written 30 March 1888 in Arles". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Maurer, 59

- ^ a b "Still Life with Books". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "A Pair of Shoes, 1886". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ Beaujean, 35

- ^ Galbally, 135-137.

- ^ a b "Glass of Absinthe and a Carafe, 1887". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b Lanier, 80.

- ^ a b Lanier, 93.

- ^ Wallace, 76

- ^ a b Maurer, 58

- ^ a b Thomson, 47-48.

- ^ Thomson, 48

- ^ Thomson, 47

- ^ a b Crispino, PT 27

- ^ "Le restaurant de la Sirène à Asnières". 2006. Musee d'Orsay. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen p. 10

- ^ Galbally pp. 145–146

- ^ Beaujean, 32-33

General and cited references

[edit]- Balakian, A; Balakian, A.E. (2008). Symbolist movement in the literature of European languages. Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-963-05-3895-4.

- Beaujean, D (2000). Van Gogh: Life and Work. Cologne: Konemann. ISBN 3-8290-2938-1

- Crispino, E (2008). Van Gogh. Minneapolis: The Oliver Press.

- Fell, D (1997) [1994]. The Impressionist Garden. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 0-7112-1148-5.

- Fell, D (2001). Gogh's Gardens. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0233-3.

- Fell, D (2005) [2004]. Van Gogh's Women: Vincent's Love Affairs and Journey Into Madness. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1655-X.

- Galbally, A (2008). A remarkable friendship: Vincent van Gogh and John Peter Russell. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-85376-6.

- Hamilton, G (1993) [1967]. Painting and Sculpture in Europe: 1880-1940. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05649-4.

- Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.

- Lanier, D. (1995) Absinthe the Cocaine of the Nineteenth Century. Jefferson, NC: McFarlane. ISBN 0-7864-1967-9.

- Mancoff, D (2008). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.

- Maurer, N (1999) [1998]. The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Cranbury: Associated University Presses. p. 63. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- Munro, E (1974). The Encyclopedia of Art. New York: Golden Press.

- Ross, B (208). Venturing Upon Dizzy Heights: Lectures and Essays on Philosophy, Literature and the Arts. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Silverman, D (2000).Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-28243-9.

- Thomson, B. (2001) Van Gogh. New York: Harry N. Abrams with Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 0-8109-6738-3.

- Tralbaut, M (1981) [1969]. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London 1969 (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974 and Alpine Fine Art Collections, 1981. ISBN 0-933516-31-2.

- Turner, J. (2000). From Monet to Cézanne: late 19th-century French artists. Grove Art. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22971-2

- Van Gogh, V and Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H, Berends-Albert, M. ed. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books.

- Wallace, R. (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853–1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books.