People's Army of Vietnam

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

| Vietnam People's Army | |

|---|---|

| Quân đội nhân dân Việt Nam | |

Emblem | |

"Determined to win" military flag | |

| Motto | Quyết thắng ("Determined to win") |

| Founded | 22 December 1944 |

| Current form | July 7, 1976 (formal unification of the NVA and the LASV)[1] |

| Service branches |

|

| Headquarters | Ministry of National Defence, Number 7 Nguyễn Tri Phương road, Điện Biên Ba Đình, Hà Nội |

| Website | Official website |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Secretary of the Central Military Commission | |

| Minister of National Defence | |

| Chief of the General Staff | |

| Director of the General Department of Political Affairs | |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 18–25 years old (18–27 for those who attend colleges or universities) |

| Conscription | 2 year 7 month |

| Active personnel | 600,000[3] (ranked 7th) |

| Reserve personnel | 5,000,000[3] |

| Expenditure | |

| Budget | US$ 7.8 billion (2023)[4] |

| Percent of GDP | ~1.6% (2023; projected)[4] |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers |

|

| Foreign suppliers | Historical: |

| Related articles | |

| History | Military history of Vietnam

List of engagements

|

| Ranks | Military ranks of Vietnam |

The People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), officially the Vietnam People's Army (VPA;[11] Vietnamese: Quân đội nhân dân Việt Nam, lit. 'Military of and for the people of Vietnam'[12]), also recognized as the Vietnamese Army (Vietnamese: Quân đội Việt Nam, lit. 'Military of Vietnam'), the People's Army (Vietnamese: Quân đội Nhân dân) or colloquially the Troops (Bộ đội), is the national military force of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the armed wing of the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). The PAVN is the backbone component of the Vietnam People's Armed Forces and includes: Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, Border Guard and Coast Guard. Vietnam does not have a separate and formally-structured Ground Force or Army service. Instead, all ground troops, army corps, military districts and special forces are designated under the umbrella term combined arms (Vietnamese: binh chủng hợp thành) and are belonged to the Ministry of National Defence, directly under the command of the CPV Central Military Commission, the Minister of National Defence, and the General Staff of the Vietnam People's Army. The military flag of the PAVN is the National flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam defaced with the motto Quyết thắng (Determination to win) added in yellow at the top left (or by the side of the flagpole).

During the French Indochina War (1946–1954), the PAVN was often referred to as the Việt Minh. In the context of the Vietnam War (1955–1975), the army was referred to by its opposition forces as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA; Vietnamese: Quân đội Bắc Việt), serving as the military force of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. This allowed writers, the U.S. military, and the general public, to distinguish northern communists from the southern communists, called Viet Cong (VC), or more formally the National Liberation Front. However, both groups ultimately worked under the same command structure. The Viet Cong had its own military forces called the Liberation Army of South Vietnam (LASV). It was practically considered a branch of the PAVN by the North Vietnamese.[13] In 1976, following the political reunification of Vietnam, LASV was officially disbanded and merged into the so-called NVA to form the existing incarnation of PAVN, serving as the national military of the unified state of Socialist Republic of Vietnam.[14]

History

Before 1945

The first historical record of Vietnamese military history dates back to the era of Hồng Bàng, the first recorded state in ancient Vietnam to have assembled military force. Since then, military plays a crucial role in developing Vietnamese history due to its turbulent history of wars against China, Champa, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand.

The Southern expansion of Vietnam resulted in the destruction of Champa as an independent nation to a level that it did not exist anymore; total destruction of Luang Prabang; the decline of Cambodia which resulted in Vietnam's annexation of Mekong Delta and wars against Siam. In most of its history, the Royal Vietnamese Armed Forces was often regarded to be one of the most professional, battle-hardened and heavily trained armies in Southeast Asia as well as Asia in a large extent.

Establishment

The PAVN was first conceived in September 1944 at the first Revolutionary Party Military Conference as the Propaganda Unit of the Liberation Army (alternatively translated as the Vietnam Propaganda Liberation Army, Việt Nam Tuyên truyền Giải phóng Quân) to educate, recruit and mobilise the Vietnamese to create a main force to drive the French colonial and Japanese occupiers from Vietnam.[15][16] Under the guidelines of Hồ Chí Minh, Võ Nguyên Giáp was given the task of establishing the brigades and the Propaganda Unit of the Liberation Army came into existence on 22 December 1944. The first formation was made up of thirty-one men and three women, armed with two revolvers, seventeen rifles, one light machine gun, and fourteen breech-loading flintlocks.[17] It fought the PAVN's first ever engagement at the Battles of Khai Phat and Na Ngan against French soldiers in late 1944. The United States' OSS agents, led by Archimedes Patti – who was sometimes referred as the first instructor of the PAVN due to his role - had provided ammunitions as well as logistic intelligence and equipment. They also helped train these soldiers, who formed the backbone of the Vietnamese military to successfully fight the Japanese and other opponents. For instance, the PAVN's July 19, 1945 attack at Tam Dao internment camp in Tonkin saw 500 soldiers kill fifty Japanese soldiers and officials, freeing French civilian captives and escorting them to the Chinese border. The PAVN also fought the Japanese 21st Division in Thai Nguyen that year, and regularly raided rice storehouses to alleviate an ongoing famine.[18]

There was another separate communist army called the National Salvation Army (Cứu quốc quân) which was founded and commanded by Chu Văn Tấn on 23/2/1941.

On 15/5/1945 the Propaganda Liberation Army merged with the National Salvation Army into the Vietnam Liberation Army (Việt Nam Giải phóng Quân) on 15 May 1945.[19] The Democratic Republic of Vietnam was proclaimed in Hanoi by Ho Chi Minh and Vietminh on 2 September 1945. Then in September, the army was renamed the Vietnam National Defence Force (Việt Nam Vệ quốc Đoàn).[20][19] At this point, it had about 1,000 soldiers.[19] On 22 May 1946, the army was called the National Army of Vietnam (Quân đội Quốc gia Việt Nam, not to be confused with the opposite Vietnamese National Army of the France-associated State of Vietnam which had a synonymous English name and exactly the same Vietnamese name). Lastly, in 1950, it officially became the People's Army of Vietnam (or Vietnam People's Army, Quân đội Nhân dân Việt Nam).[16]

Võ Nguyên Giáp went on to become the first full general of the PAVN on 28 May 1948, and famous for leading the PAVN in victory over French forces at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954 and being in overall command against U.S. backed South Vietnam at the Liberation of Saigon on 30 April 1975.

French Indochina War

On 7 January 1947, its first regiment, the 102nd 'Capital' Regiment, was created for operations around Hanoi.[21] Over the next two years, the first division, the 308th Division, later well known as the Pioneer Division, was formed from the 88th Tu Vu Regiment and the 102nd Capital Regiment. By late 1950 the 308th Division had a full three infantry regiments, when it was supplemented by the 36th Regiment. At that time, the 308th Division was also backed by the 11th Battalion that later became the main force of the 312th Division. In late 1951, after launching three campaigns against three French strongpoints in the Red River Delta, the PAVN refocused on building up its ground forces further, with five new divisions, each of 10–15,000 men, created: the 304th Glory Division at Thanh Hóa, the 312th Victory Division in Vinh Phuc, the 316th Bong Lau Division in the northwest border region, the 320th Delta Division in the north Red River Delta, the 325th Binh Tri Thien Division in Binh Tri Thien province. Also in 1951, the first artillery Division, the 351st Division was formed, and later, before Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, for the first time in history, it was equipped with 24 captured 105mm US howitzers supplied by the Chinese People's Liberation Army. The first six divisions (308th, 304th, 312th, 316th, 320th, 325th) became known as the original PAVN 'Steel and Iron' divisions. In 1954, four of these divisions (the 308th, 304th, 312nd, 316th, supported by the 351st Division's captured US howitzers) defeated the French Union forces at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, ending 83 years of French rule in Indochina.

The French Foreign Legion had been deployed to combat the Vietnamese insurgency during the First Indochina War. However, some of the legionnaires, such as Stefan Kubiak, deserted after witnessing torture of Vietnamese peasants at the hands of French troops and began fighting for the Việt Minh, volunteering to join the PAVN.[22][23][24]

Vietnam War

Soon after the 1954 Geneva Accords, the 330th and 338th Divisions were formed by southern Viet Minh members who had moved north in conformity with that agreement, and by 1955, six more divisions were formed: the 328th, 332nd and 350th in the north of the North Vietnam, the 305th and the 324th near the DMZ, and the 335 Division of soldiers repatriated from Laos. In 1957, the theatres of the war with the French were reorganised as the first five military regions, and in the next two years, several divisions were reduced to brigade size to meet the manpower requirements of collective farms.

By 1958, it was becoming increasingly clear that the South Vietnamese government was solidifying its position as an independent republic under Ngô Đình Diệm, who staunchly opposed the terms of the Geneva Accords, which required a national referendum on unification of north and south Vietnam under a single national government. North Vietnam prepared to settle the issue of unification by force.

In May 1959, the first major steps to prepare infiltration routes into South Vietnam were taken; Group 559 was established, a logistical unit charged with establishing routes into the south via Laos and Cambodia, which later became famous as the Ho Chi Minh trail. At about the same time, Group 579 was created as its maritime counterpart to transport supplies into the South by sea. Most of the early infiltrators were members of the 338th Division, former southerners who had been settled at Xuan Mai from 1954 onwards.

Regular formations were sent to South Vietnam from 1965 onwards; the 325th Division's 101B Regiment and the 66th Regiment of the 304th Division met U.S. forces on a large scale, a first for the PAVN, at the Battle of Ia Drang in November 1965. The 308th Division's 88A Regiment, the 312th Division's 141A, 141B, 165A, 209A, the 316th Division's 174A, the 325th Division's 95A, 95B, the 320A Division also faced the U.S. forces which included the 1st Cavalry Division, the 101st Airborne Division, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the 4th Infantry Division, the 1st Infantry Division and the 25th Infantry Division. Many of those formations later became main forces of the 3rd Division (Yellow Star Division) in Binh Dinh (1965), the 5th Division (1966) of 7th Military Zone (Capital Tactical Area of ARVN), the 7th (created by 141st and 209th Regiments originated in the 312th Division in 1966) and 9th Divisions (first Division of National Liberation Front of Vietnam in 1965 in Mekong Delta), the 10th Dakto Division in Dakto – Central Highlands in 1972.

On 20 December 1960, anti-government forces in South Vietnam joined to form a united front called National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng Miền Nam Việt Nam) or simply known as the Vietcong in the United States. On 15 December 1961, the NLF established its own military called Liberation Army of South Vietnam (LASV) to fight against the American supported Army of the Republic of Vietnam. The LASV was controlled and equipped by the PAVN.

General Trần Văn Trà, one-time commander of the B2 Front (Saigon) HQ confirms that even though the PAVN and the LASV were confident in their ability to defeat the regular ARVN forces, U.S. intervention in Vietnam forced them to reconsider their operations. The decision was made to continue to pursue "main force" engagements even though "there were others in the South – they were not military people – who wanted to go back to guerrilla war," but the strategic aims were adjusted to meet the new reality.

We had to change our plan and make it different from when we fought the Saigon regime, because we now had to fight two adversaries — the United States and South Vietnam. We understood that the U.S. Army was superior to our own logistically, in weapons and in all things. So strategically we did not hope to defeat the U.S. Army completely. Our intentions were to fight a long time and cause heavy casualties to the United States, so the United States would see that the war was unwinnable and would leave.[25]

During the Vietnamese Lunar New Year Tết holiday starting on 30 January 1968, the PAVN/VC launched a general offensive in more than 60 cities and towns throughout south of Vietnam against the US Army and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), beginning with operations in the border region to try and draw US forces and ARVN troops out of the major cities. In coordinated attacks, the U.S Embassy in Saigon, Presidential Palace, Headquarters of the Joint General Staff and Republic of Vietnam Navy, TV and Radio Stations, Tan Son Nhat Air Base in Saigon were attacked by commando forces known as "đặc công". This offensive became known as the "Tet Offensive". The PAVN sustained heavy losses of its main forces in southern military zones. Some of its regular forces and command structure had to escape to Laos and Cambodia to avoid counterattacks from US forces and ARVN, while local guerrillas forces and political organisations in South Vietnam were exposed and had a hard time remaining within the Mekong Delta area due to the extensive use of the Phoenix Program.

Although the PAVN lost militarily to the US forces and ARVN in the south, the political impact of the war in the United States was strong.[26] Public demonstrations increased in ferocity and quantity after the Tet Offensive. During 1970, the 5th, 7th and 9th Divisions fought in Cambodia against U.S., ARVN, and Cambodian Khmer National Armed Forces but they had gained new allies: the Khmer Rouge and guerrilla fighters supporting deposed Prime Minister Sihanouk. In 1975 the PAVN were successful in aiding the Khmer Rouge in toppling Lon Nol's U.S.-backed regime, despite heavy US bombing.

After the withdrawal of most U.S. combat forces from Indochina because of the Vietnamization strategy, the PAVN launched the ill-fated Easter Offensive in 1972. Although successful at the beginning, the South Vietnamese repulsed the main assaults with U.S. air support. Still North Vietnam retained some South Vietnamese territory.

Nearly two years after the full U.S. withdrawal from Indochina in accordance with the terms of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, the PAVN launched a Spring offensive aimed at overthrowing the South Vietnamese government and uniting Vietnam under communist rule. Without direct support of the U.S., and suffering from stresses caused by dwindling aid, the ARVN was ill-prepared to confront the highly motivated PAVN, and despite the on paper superiority of the ARVN, the PAVN quickly secured victory within two months and captured Saigon on 30 April 1975, ending the 20 year Vietnam war.

After national reunification, the LASV was officially merged into PAVN on 2 July 1976.

Sino-Vietnamese conflicts (1975–1991)

Towards the second half of the 20th century the armed forces of Vietnam would participate in organised incursions to protect its citizens and allies against aggressive military factions in the neighbouring Indochinese countries of Laos and Cambodia, and the defensive border wars with China.

- The PAVN had forces in Laos to secure the Ho Chi Minh trail and to militarily support the Pathet Lao. In 1975 the Pathet Lao and PAVN forces succeeded in toppling the Royal Laotian regime and installing a new, and pro-Hanoi government, the Lao People's Democratic Republic,[27] that rules Laos to this day.

- Parts of Sihanouk's neutral Cambodia were occupied by troops as well. A pro US coup led by Lon Nol in 1970 led to the foundation pro-US Khmer Republic state. This marked the beginning of the Cambodian Civil War. The PAVN aided Khmer Rouge forces in toppling Lon Nol's government in 1975. In 1978, along with the FUNSK Cambodian Salvation Front, the Vietnamese and Ex-Khmer Rouge forces succeeded in toppling Pol Pot's Democratic Kampuchea regime and installing a new government, the People's Republic of Kampuchea.[28]

- During the Sino-Vietnamese War and the Sino-Vietnamese conflicts (1979–1991), Vietnamese forces would conduct cross-border raids into Chinese territory to destroy artillery ammunition. This greatly contributed to the outcome of the Sino-Vietnamese War, as the Chinese forces ran out of ammunition already at an early stage and had to call in reinforcements.

- While occupying Cambodia, Vietnam launched several armed incursions into Thailand in pursuit of Cambodian guerrillas that had taken refuge on the Thai side of the border.

Modern deployment

The PAVN has been actively involved in Vietnam's workforce to develop the economy of Vietnam by co-ordinating national defence. It has regularly sent troops to aid with natural disasters such as flooding, landslides etc. The PAVN is also involved in such areas as industry, agriculture, forestry, fishery and telecommunications. The PAVN has numerous small firms which have become quite profitable in recent years. However, recent decrees have effectively prohibited the commercialisation of the military. Conscription is in place for theoretically every male, age 18 to 25 years old, with the exception of the disabled and men who attended universities right after high school.

International presence & operations

The Foreign Relations Department of the Ministry of National Defence organises international operations of the PAVN.

Apart from its occupation of half of the disputed Spratly Islands, which have been claimed as Vietnamese territory since the 17th century, Vietnam has not officially had forces stationed internationally since its withdrawal from Cambodia and Laos in early 1990.

Allegations of Vietnamese assistance for overseas leftist insurgencies

The effectiveness of the People's Army of Vietnam Special Operation Forces during the Vietnam War saw them instruct various other countries and Marxist rebel groups. From the 1970s to 1990s, they covertly provided training at the PAVN Sapper Training School in via Vietnamese sapper advisors assigned to the Cuban Army's Sapper School in Cuba, and, during the 1980s, by a secret Vietnamese sapper training team stationed in Nicaragua. In addition to training Cambodian, Laotian, Soviet, and Cuban military personnel, their publications revealed that among the foreign revolutionary forces that received training in sapper tactics, bomb-making, and the use of weapons and explosives, were members of the Marxist El Salvadoran FMLN (Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front), the Chilean MIR (Movement of the Revolutionary Left) fighting against the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet, as well as the Colombian FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) movement, a Marxist guerilla group.[29]

Allegations of Vietnamese intervention in Lao security crises

The Center for Public Policy Analysis and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as well as Laotian and Hmong human rights organisations, including the Lao Human Rights Council, Inc. and the United League for Democracy in Laos, Inc., have provided evidence that since the end of the Vietnam War, significant numbers of Vietnamese military and security forces continue to be sent to Laos, on a repeated basis, to quell and suppress Laotian political and religious dissident and opposition groups including the peaceful 1999 Lao Students for Democracy protest in Vientiane in 1999 and the Hmong rebellion.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]

Rudolph Rummel has estimated that 100,000 Hmong perished in genocide between 1975 and 1980 in collaboration with PAVN.[41] For example, in late November 2009, shortly before the start of the 2009 Southeast Asian Games in Vientiane, the PAVN undertook a major troop surge in key rural and mountainous provinces in Laos where Lao and Hmong civilians and religious believers, including Christians, have sought sanctuary.[42][43]

Modern-era peacekeeping operations

In 2014, Vietnam had requested to join the United Nations peacekeeping force, which was later approved.[44] The first Vietnamese UN peacekeeping officers were sent to South Sudan, marked the first involvement of Vietnam into a United Nations' mission abroad.[44] Vietnamese peacekeepers were also sent to the Central African Republic.[45]

From 2022, Vietnam has deployed its first military engineer unit to the peacekeeping missions in Abyei.[46]

2023 Turkish-Syrian earthquake

As an effort to help Turkey overcome the consequences of the 2023 earthquake, PAVN has sent 76 servicemen of the Border Guard, Army Medic, and Engineering Corps (alongside personnel from Public Security) to participate in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief including search-and-rescue missions.[47]

This is the first time ever that Vietnam has officially deployed and engaged in an overseas search and rescue campaign.

Organisation

The Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces is the President of Vietnam, though this position is nominal and real power is assumed by the Central Military Commission of the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam. The secretary of Central Military Commission (usually the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam) is the de facto Commander and now is Nguyễn Phú Trọng.

The Minister of National Defence oversees operations of the Ministry of Defence, and the PAVN. He also oversees such agencies as the General Staff and the General Department of Logistics. However, military policy is ultimately directed by the Central Military Commission of the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam.

- Ministry of National Defence: is the lead organisation, highest command and management of the Vietnam People's Army.

- General Staff: is leading agency all levels of the Vietnam People's Army, command all of the armed forces, which functions to ensure combat readiness of the armed forces and manage all military activities in peace and war.

- General Political Department: is the agency in charge of Communist Party affairs – political work within PAVN, which operates under the direct leadership of the Secretariat of the Communist Party of Vietnam and the Central Military Party Committee.

- General Department of Defence Intelligence: is an intelligence agency of the Vietnamese government and military.

- General Department of Logistics: is the agency in charge to ensure logistical support to units of the People's Army.

- General Department of Technology: is the agency in charge to ensure equipped technical means of war for the army and each unit.

- General Department of Defence Industry (commercially branded as the Vietnam Defence Industry): is the agency responsible for the development of the Vietnamese national defense industry in support of the missions of the PAVN.

Service branches

The Vietnamese People's Army is subdivided into the following service branches:

- Vietnam People's Ground Force (unofficial)

(Lục quân Nhân dân Việt Nam)

- Vietnam People's Air Force

(Không quân Nhân dân Việt Nam)

- Vietnam People's Navy

(Hải quân Nhân dân Việt Nam)

- Vietnam Border Guard

(Bộ đội Biên phòng Việt Nam)

- Vietnam Coast Guard

(Cảnh sát biển Việt Nam)

- Cyberspace Operations Command

(Bộ Tư lệnh Tác chiến không gian mạng)

- President Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum Defence Force

(Bộ Tư lệnh Bảo vệ Lăng Chủ tịch Hồ Chí Minh)

The People's Army of Vietnam composes of the standing (or regular) forces and the reserve forces. The standing forces include the main forces and the local forces. During peacetime, the standing forces are minimised in number, and kept combat-ready by regular physical and weapons training, and stock maintenance.

Vietnam People's Ground Force

Within PAVN the Ground Force have not been established as a separate full Service Command, thus all of the ground troops, army corps, military districts and the specialised arms are under the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence, under the direct command of the General Staff, who serves as its de facto commander.

Arm badges

| Infantry | Armor - Tank | Artillery | Special Forces | Ammunition | Mechanized Infantry | Engineering | Medical | Signals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Transportation | Technical | Chemical | Ordnance | Intelligence | Military Court | Ensemble | Military Athletes | Military Musical Bands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military regions

The following military regions are under the direct control of the General Staff and the Ministry of Defence:

- Hanoi Capital City Special High Command (Bộ Tư lệnh Thủ đô Hà Nội): special command tasked for the defense of the Hanoi Capital Region. Headquarters: Hanoi

- 1st Military Region (Quân khu 1): responsible for the North East of Vietnam. Headquarters: Thái Nguyên

- 2nd Military Region (Quân khu 2): responsible for the North West of Vietnam. Headquarters: Việt Trì, Phú Thọ

- 3rd Military Region (Quân khu 3): responsible for the defense of the Red River Delta (except Hanoi Capital Region). Headquarters: Hai Phong

- 4th Military Region (Quân khu 4): responsible for North Central Vietnam. Headquarters: Vinh, Nghệ An province

- 5th Military Region (Quân khu 5): responsible for South Central Vietnam including the Central Highlands and Southern Central coastal provinces. Headquarters: Da Nang

- 7th Military Region (Quân khu 7): responsible for Southeast Vietnam. Headquarters: Ho Chi Minh City

- 9th Military Region (Quân khu 9): responsible for the Mekong Delta. Headquarters: Cần Thơ

Main forces

| Vietnam People's Army |

|---|

|

| Ministry of National Defence |

| Command |

| General Staff |

| Services |

| Ranks and history |

The Main Force of the PAVN and its People's Ground Forces consists of combat ready troops, as well as support units such as educational institutions for logistics, officer training, and technical training. In 1991, Conboy et al. stated that the PAVN Ground Force had four 'Strategic Army Corps' in the early 1990s, numbering 1–4, from north to south.[48] 1st Corps, located in the Red River Delta region, consisted of the 308th (one of the six original 'Steel and Iron' divisions) and 312th Divisions, and the 309th Infantry Regiment. The other three corps, 2 SAC, 3 SAC, and 4 SAC, were further south, with 4th Corps, in Southern Vietnam, consisting of two former LASV divisions, the 7th and 9th.

From 2014 to 2016, the IISS Military Balance attributed the Vietnamese ground forces with an estimated 412,000 personnel. Formations, according to the IISS, include 8 military regions, 4 corps headquarters, 1 special forces airborne brigade, 6 armoured brigades and 3 armoured regiments, two mechanised infantry divisions, and 23 active infantry divisions plus another 9 reserve ones.

Combat support formations include 13 artillery brigades and one artillery regiment, 11 air defence brigades, 10 engineers brigades, 1 electronic warfare unit, 3 signals brigades and 2 signals regiment.

Combat service support formations include 9 economic construction divisions, 1 logistical regiment, 1 medical unit and 1 training regiment. Ross wrote in 1984 that economic construction division "are composed of regular troops that are fully trained and armed, and reportedly they are subordinate to their own directorate in the Ministry of Defense. They have specific military missions; however, they are also entrusted with economic tasks such as food production or construction work. They are composed partially of older veterans."[49] Ross also cited 1980s sources saying that economic construction divisions each had a strength of about 3,500.

In 2017, the listing was amended, with the addition of a single Short-range ballistic missile brigade. The ground forces according to the IISS, hold Scud-B/C SRBMs.[50]

First organised on 21 November 2023, the 12th Corps was created by merging all of the units from the former 1st Corps and the 2nd Corps. It is stationed in Tam Điệp District, Ninh Bình.[51][52]

3rd Corps – Binh đoàn Tây Nguyên (Corps of the Central Highlands):

First organised on 26 March 1975 during the Vietnam War, 3rd Corps had a major role in the Ho Chi Minh campaign and the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. Stationed in Pleiku, Gia Lai.

![]() 4th Corps – Binh đoàn Cửu Long

(Corps of the Mekong):

4th Corps – Binh đoàn Cửu Long

(Corps of the Mekong):

First organised 20 July 1974 during the Vietnam War, 4th Corps had a major role in the Ho Chi Minh campaign and the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. Stationed in Dĩ An, Bình Dương

Local forces

Local forces are an entity of the PAVN that, together with the militia and "self-defence forces", act on the local level in protection of people and local authorities. While the local forces are regular VPA forces, the people's militia consists of rural civilians, and the people's self-defence forces consist of civilians who live in urban areas and/or work in large groups, such as at construction sites or farms. The current number stands at 3–4 million reservists and militia personnel combined. They serve as force multipliers to the PAVN and Public Security during wartime and peacetime contingencies.

Vietnam People's Navy

Vietnam People's Air Force

Vietnam Border Guard

Vietnam Coast Guard

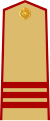

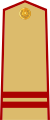

Ranks and insignia

Commissioned officer ranks

The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Đại tướng | Thượng tướng | Trung tướng | Thiếu tướng | Đại tá | Thượng tá | Trung tá | Thiếu tá | Đại úy | Thượng úy | Trung úy | Thiếu úy | |||||||||||||

Other ranks

The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thượng sĩ | Trung sĩ | Hạ sĩ | Binh nhất | Binh nhì | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Equipment

From the 1960s to 1975 the Soviet Union, along with some smaller Eastern Bloc countries, was the main supplier of military hardware to North Vietnam. After the latter's victory in the war, it remained the main supplier of equipment to Vietnam. The United States had been the primary supplier of equipment to South Vietnam; much of the equipment left by the U.S. Army and the ARVN came under control of the re-unified Vietnamese government. The PAVN captured large numbers of ARVN weapons on 30 April 1975 after Saigon was captured.

Russia remains the largest arms-supplier for Vietnam; even after 1986, there were also increasing arms sales from other nations, notably from India, Turkey, Israel, Japan, South Korea, and France. In 2016, President Barack Obama announced the lifting of the lethal weapons embargo on Vietnam, which has increased Vietnamese military equipment choices from other countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and other Western countries, which could enable a faster modernization of the Vietnamese military. Since 2018, the United States has begun to provide warships for Vietnam Coast Guard as part of the military cooperation between two states, the first of these ships arrived in 2021.[54]

Despite Russia remaining Vietnam's largest weapon supplier, increasing cooperation with Israel has resulted in the development of Vietnamese weaponry with a strong mixture of Russian and Israeli weapons. For examples, the PKMS, GK1, and GK3 guns are three Vietnam-made indigenous guns modeled after the Galil ACE of Israel.[55] Many new Vietnamese weapons, armor, and equipment are also greatly influenced by Israeli military doctrines, due to Vietnam's long and problematic relations with most of its neighbors.[55]

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ "KỶ NIỆM 50 NĂM NGÀY THÀNH LẬP QUÂN GIẢI PHÓNG MIỀN NAM VIỆT NAM (15-2-1961 – 15-2-2011):Trang sử vàng của Quân Giải phóng miền Nam". Báo Đà Nẵng (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "Scope of operation, working measures and international cooperation of the Vietnam Coast Guard". National Defence Journal. Ministry of Defence (Vietnam).[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b International Institute for Strategic Studies (3 February 2014). The Military Balance 2014. London: Routledge. pp. 287–289. ISBN 9781857437225.

- ^ a b "Resolution no. 70/2022/QH15 of the National Assembly on the Distribution of Central Budget of 2023". National Assembly of Vietnam. 30 November 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "D&S 2019: Vietnam domestically upgrades T-54B tanks | Shephard". shephardmedia.com. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "Song Thu Corporation Launches Third Vietnam People's Navy Roro 5612 Landing Ship". 2 July 2020.

- ^ Kobus. "Vietnam to make unmanned aircraft". zimbio.com. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Defense mission works with Factory A32". en.qdnd.vn. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Wozniak, Jakub (20 October 2020). "Japan and Vietnam Reach Agreement on Arms Exports to Vietnam". Overt Defense.

- ^ "History – The Hmong". Cal.org. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Vietnam People's Army". Ministry of National Defence.

- ^ "Ho Chi Minh's thought on building the Army with "politics being taken as the roots" – significance and practical values". National Defence Journal. Ministry of Defence (Vietnam). Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

Ours is an army 'from the people, for the people, readily fighting and sacrificing for the independence of the Fatherland and nation, for the happiness of the people'

- ^ Military History Institute of Vietnam,(2002) Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975, translated by Merle L. Pribbenow. University Press of Kansas. p. 68. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- ^ Diệu Linh. "Quân giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam và những bài học lịch sử". VOV2 (in Vietnamese). Voice of Vietnam. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Leulliot, Nowfel. "Viet Minh". free.fr. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Vietnam People's Army, foundation and development". Viet Nam Ministry of National Defence. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Macdonald, Peter (1993). Giap: The Victor in Vietnam, pp. 32

- ^ Hanyok, Robert (1995). "Guerillas in the Mist: COMINT and the Formation and Evolution of the Viet Minh 1941-45". (p.107).

- ^ a b c "Early Days :The Development of the Viet Minh Military Machine". indochine54.free.fr. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "Cổng TTĐT Bộ Quốc phòng Việt Nam". mod.gov.vn.

- ^ Conboy, Bowra, and McCouaig, The NVA and Vietcong, Osprey Publishing, 1991, p.5

- ^ Hoàng Lam (29 April 2014). "Chuyện về người lính lê dương mang họ Bác Hồ". dantri.com.vn. Dân trí. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ Rodak, Wojciech (24 March 2017). "Ho Chi Toan. Jak polski dezerter został bohaterem ludowego Wietnamu". naszahistoria.pl. NaszaHistoria.pl. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ Schwarzgruber, Małgorzata (18 February 2015). "Ho Chi Toan - Polak w mundurze wietnamskiej armii". wiadomosci.wp.pl. Wirtualna Polska. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Interview with PAVN General Tran Van Tra". 12 June 2006. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "Political lessons – The Vietnam War and Its Impact". Americanforeignrelations.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Christopher Robbins, The Ravens: Pilots of the Secret War in Laos. Asia Books 2000.

- ^ David P. Chandler, A history of Cambodia, Westview Press; Allen & Unwin, Boulder, Sydney, 1992

- ^ Pribbenow, Merle. "Vietnam Trained Commando Forces in Southeast Asia and Latin America". Wilson Center.

- ^ Centre for Public Policy Analysis Archived 6 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, (CPPA),(30 August 2013), Washington, D.C.

- ^ The Hmong Rebellion in Laos: Victims of Totalitarianism or terrorists? Archived 14 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, by Gary Yia Lee, PhD

- ^ "Vietnamese soldiers attack Hmong in Laos". Factfinding.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Joint-Military Co-operation continues between Laos and Vietnam". Factfinding.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Combine Military Effort of Laos and Vietnam". Factfinding.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Vietnam, Laos: Military Offensive Launched At Hmong". Rushprnews.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Laos, Vietnam: Attacks Against Hmong Civilians Mount". cppa-dc.org/id41.html. 20 May 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Laos, Vietnam: New Campaign to Exterminate Hmong". Prlog.org. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "President Obama Urged To Address Laos, Hmong Crisis During Asia Trip, Student Protests in Vientiane". Pr-inside.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Hmong: Vietnam VPA, LPA Troops Attack Christians Villagers in Laos". Unpo.org. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Laos, Vietnam Peoples Army Unleashes Helicopter Gunship Attacks on Laotian and Hmong Civilians, Christian Believers". Nickihawj.blogspot.com. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Statistics of Democide Archived 4 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Rudolph Rummel

- ^ "Vietnam, Laos Crackdown: SEA Games Avoided By Overseas Lao, Hmong in Protest". Onlineprnews.com. 7 December 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Media-Newswire.com – Press Release Distribution (26 November 2009). "SEA Game Attacks: Vietnam, Laos Military Kill 23 Lao Hmong Christians on Thanksgiving". Media-newswire.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b "What's in Vietnam's New Peacekeeping Boost?".

- ^ "Seven more Vietnam military officers to join UN peacekeeping forces - VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ VNA (3 April 2022). "Preparations completed for Vietnam's first military engineer unit to a UN peacekeeping mission | Politics | Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus)". VietnamPlus. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Vietnam People's Army sends 76 servicemen to participate in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief in Turkey". People's Army Newspaper Online. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Modern Military of Vietnam". Defence Talk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Ross 1984, p. 17.

- ^ IISS Military Balance 2017, 338–9.

- ^ "Thành lập Quân đoàn 12, tiến lên hiện đại". Vietnamese Government. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ "Lãnh đạo Quân ủy Trung ương, Bộ Quốc phòng dự lễ công bố Quyết định thành lập Quân đoàn 12". People's Army Newspaper. Vietnam. 2 December 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Quy định quân hiệu, cấp hiệu, phù hiệu và lễ phục của Quân đội nhân dân Việt Nam". mod.gov.vn (in Vietnamese). Ministry of Defence (Vietnam). 26 August 2009. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Donates patrol vessel to boost Vietnam's maritime security | Indo-Pacific Defense Forum". 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Chế tuyệt tác vũ khí, Công nghiệp quốc phòng VN 'đứng trên vai người khổng lồ" Israel". soha.vn. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

References

- Conboy, Bowra, and McCouaig, 'The NVA and Vietcong', Osprey Publishing, 1991.

- Gabriel, Richard A. "Nonaligned, Third World, and Other Ground Armies: A Combat Assessment," Greenwood Press, 1983. Nonaligned, Third World, and Other Ground Armies: A Combat Assessment (further reading)

- Military History Institute of Vietnam,(2002) Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975, translated by Merle L. Pribbenow. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- Morris, Virginia and Hills, Clive. 'Ho Chi Minh's Blueprint for Revolution: In the Words of Vietnamese Strategists and Operatives', McFarland & Co Inc, 2018.

- Ross, Russell R. (1984). "Military Force Development in Vietnam: A Report" (PDF). Washington DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.

- Thayer, Carl A. (1997). "Force Modernization: The Case of the Vietnam People's Army". Contemporary Southeast Asia; Singapore. 19 (1).

- Tran, Doan Lam (2012). How the Vietnamese People's Army was Founded. Hanoi: World Publishers. ISBN 978-604-7705-13-9.