Orthodox Peronism

Orthodox Peronism Peronismo Ortodoxo | |

|---|---|

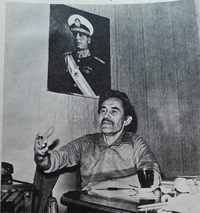

José Ignacio Rucci was the most important orthodox traditional sindicalist. | |

| Leader | Isabel Perón José López Rega (until July 9, 1975) José Ignacio Rucci Ítalo Lúder Juan Domingo Perón Norma Kennedy Jorge Osinde |

| Founded | 1965 |

| Succeeded by | Peronist Renovation |

| Membership | Justicialist Party |

| Ideology | Peronism[1] Third Position[2] Syndicalism[3] Corporatism[4] Revisionist nationalism[5] Conservatism[6] Faction that governed: Right-wing peronism[7] Right-wing populism[8] Neoliberalism[A] Authoritarianism[9][10] Homophobia[11][12] Antisemitism[13] Anti-communism[14] Anti-synarchism[15] Anti-capitalism[16] Anti-Marxism[17] Fascism[18][19][20][21] Falangism[22][21] Nazism[21] Rosism[23] |

| Political position | Faction that governed: Far-right[24][2][25] Factions: Centre[26][27][28][25] |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Regional affiliation | Propaganda Due |

^ A: The orthodox peronist economic management in the government of Isabel Perón, was labeled as neoliberal.[29] | |

Orthodox Peronism, Peronist Orthodoxy, National Justicialism,[30] or right-wing peronism for some specialists,[31] is a faction within Peronism, a political movement in Argentina that adheres to the ideology and legacy of Juan Perón. Orthodox Peronists are staunch supporters of Perón and his original policies, and they reject any association with Marxism or any other left-wing ideologies. Some of them are aligned with far-right elements.[32] Orthodox Peronism also refers to the Peronist trade union faction that split from the “62 organizations" and that opposed the “legalists", who were more moderate and pragmatic. They were also known as “the hardliners", “the 62 standing with Perón" and they maintained an orthodox and verticalist stance, in accordance with the Peronist doctrine.[33] Orthodox Peronism has been in several conflicts with the Tendencia Revolucionaria (opposite current in the Peronist movement), for example during the Ezeiza massacre.

Origin of the denomination

[edit]The term "orthodox Peronism" emerged during the Peronist resistance following the 1955 coup, a period when historical revisionism took hold, deepening the connection between Peronism and nationalism. While the Peronist government had some ties with nationalists, it had not embraced a revisionist historical view, and the nationalists did not play a dominant role in government policy. It was only after 1955, amidst the context of resistance and under the influence of nationalist thought, that orthodox Peronism began to take shape. This marked a dual process: Peronism began adapting to nationalist ideals, while nationalists reappropriated and redefined key elements of Perón’s original discourse.

This convergence was fraught with tensions. The most intransigent and uncompromising sectors of Peronism emerged during this time, rejecting any form of negotiation with the government. These groups distanced themselves from the more conciliatory tendencies that arose within Peronism in the 1960s, including the neoperonist and vandorist factions. When referring to the traditional orthodox current, it is important to recognize a coalition of unions and organizations that, despite their loyalty to Peronist verticality, initially opposed leaders like Rodolfo Ponce and right-wing unionism. Many of these union leaders gained their influence during the labor conflicts of the early 1960s, such as the "Plan de Huerta Grande" and the "Plan de Lucha" in 1964. This orthodox faction was largely represented by the Secretaries of the AEC (Ezequiel Crisol) and the UOM (Albertano Quiroga), supported by unions with large memberships, though they wielded limited political influence at the time.

Peronism underwent a profound transformation during the campaign "Luche y Vuelve", which culminated in Perón's return to power in 1973. Tensions between the union sectors and the Peronist left, which had backed Cámpora’s government, escalated when Perón took office. The far-left faction of Peronism represented by the Montoneros entered a conflict with the Peronist trade unions, which forced Perón to give concessions to labour bureucracy and act against the left-wing Peronists, given the threat of trade unions turning against Perón.[34] According to Ronaldo Munck, Perón did not differ from Tendencia Revolucionaria in terms of economic ideology, but rather mass mobilisation: "The purely anti-imperialist and anti-oligarchic political programme of the Montoneros ("national socialism") was not incompatible with Peron's economic project of "national reconstruction", but their power of mass mobilisation was."[35] The traditional Peronist sectors—union orthodoxy and right-wing Peronists—formed a verticalist alliance that established a new Peronist orthodoxy. This group sought to marginalize and suppress the left-wing faction of the movement, which held onto its revolutionary ideals.

Orthodox Peronism from this point onward came to represent the factions that, in the name of verticalism, opposed any alignment with Marxism or the Peronist left. Those loyal to Perón and his wife, Isabel Martínez de Perón, began to identify themselves as orthodox Peronists, defending the "Peronist homeland" against the "socialist homeland" advocated by the left-wing Revolutionary Tendency. During Raúl Lastiri’s interim presidency and after Perón’s death, this new orthodox coalition used both institutional and extralegal means to push out and marginalize the left-wing heterodoxy, which included leftist Peronists and their aligned governors and officials. This led to increased political violence within the Peronist movement, further aggravated by armed guerrilla activities, marking one of the most violent periods in Argentina’s history.[32][23]

Ideology

[edit]Until 1973

[edit]Initially, orthodox Peronism encompassed those Peronist sectors that followed the Peronist ideals to the letter and opposed the neo-Peronist sectors of the time, as Perón expressed in his speeches:

“We have, yes, an ideology and a doctrine within which we are developing. Some are on the right of that ideology and others are on the left, but they are in the ideology. Those on the right protest because these on the left are, and those on the left protest because those on the right are, and I don’t know which of the two is right in the protest. But that is something that does not interest me."(english) [“Tenemos, sí, una ideología y una doctrina dentro de la cual nos vamos desarrollando. Algunos están a la derecha de esa ideología y otros están a la izquierda, pero están en la ideología. Los de la derecha protestan porque estos de la izquierda están, y los de la izquierda protestan porque están los de la derecha, y yo no sé cuál de los dos tiene razón en la protesta. Pero esa es una cosa que a mí no me interesa."] (spanish)

— Juan Domingo Perón, 8 de setiembre de 1973

It was mainly organized under the orthodox union leadership. This traditional orthodoxy was part of the National Transference Table.

Since 1973

[edit]With the return of Perón, Orthodox Peronism mainly advocated its total adherence to the governments of Perón and Isabel Perón, highlighting that the twenty Peronist truths were relevant and nothing else (emphasizing it to the tendency); the opposition to the revolutionary youth sectors of Peronism and the "Homeland Socialist", considered alien to the movement; and the reaffirmation of the Third Position distancing itself from both United States and the Soviet Union.[2][36] Orthodox Peronism positioned itself as the opposite of the left-wing Revolutionary Peronism, objecting to the ideas of armed struggle and Marxist elements of revolutionary Peronism.[37]

Perón himself did not consider right-wing Peronists as "orthodox" or the most loyal faction; up to 1973, Perón supported the left-wing "special formations" of Peronism and denigrated several men who would later claim the label of Orthodox Peronism. Juan Luis Besoky writes that in fact many Orthodox Peronists were either newcomers to the Peronist movement, or were reluctant to follow Perón's directives, contrary to their label.[37] Even following Perón's conflict with the Montoneros between 1973 and 1974, he did not desire to abandon the Peronist left and sought to restore his trust in his last speech from June 1974, where he denounced "the oligarchy and the pressures exerted by imperialism upon his government", considered an implication that he was being manipulated by the Peronist right.[38]

The term of right-wing peronism is included within the parameter of the orthodoxy, but not only, since the term could denote old Justicialists or centrists/centre-rightists who simply wanted to distance themselves from the postulates of the tendency. The distinction of the orthodox organizations of "far right" obeys to that these last ones assumed the fight against the Marxist advance within the Peronist movement through the armed violence, with a marked antisemitic, anticommunist and antisynarchist bias.[2][39]

Fascism was also a qualification that various groups were pointed out, such as the Nationalist Liberation Alliance and the Tacuara Nationalist Movement, although both of their leaders Isabel Perón and José López Rega ("the wizard") showed tuning for fascism or falangism.[40][41][42] Perón was seen performing the roman salute characteristic of the movements akin to fascism.[43] And López Rega was part of the Masonic lodge Propaganda Due, led by the fascist Licio Gelli, and he collaborated whit fascist peronist groups.[44] Economically both showed neoliberal profiles and appointed as minister of economy Celestino Rodrigo, who applied an ultra-liberal economic program vulgarly known as "Rodrigazo".[45][46]

Orthodoxy organizations

[edit]In the seventies, there were several terrorist organizations that adhered to this Peronism. Among the main groups of Orthodox Peronism include the Orthodox Peronist Youth, with Adrián Curi as executive secretary; Concentration of the Peronist Youth, with Martín Salas as organization secretary; Peronist Union Youth, which has Claudio Mazota in t.he union secretariat; the Iron Guard, the Falangist National University Concentration; the Peronist Youth of the Argentine Republic, National Student Front, which had Víctor Lorefice as press and finance secretary, and the neo-Nazi and Antisemite organization the Tacuara Nationalist Movement is also part of this movement. The Alianza Anticomunista Argentina (AAA) also Is included, although it is not yet clear if it is its own political organization, a mere death squad, or a confederation of right-wing groups.[47] Other minor groups such as the Comando Rucci are also part of this denomination.[48]

Present

[edit]Currently the term orthodox Peronism, is still used although sometimes it is not used with historical rigor. It is used to describe groups such as the Popular Dignity party[49] (currently the Federal Republican Encounter),[50] the Second Republic Project,[51] the Popular Party,[52] the Principles and Values Party,[53][54][55] Unite for Freedom and Dignity[56] (successor of People's Countryside Party and Movement for Dignity and Independence[57]), Federal Patriot Front[58] (previously known as New Triumph Party, Alternativa Social and Bandera Vecinal), parts of Youth and Dignity Left Movement[59][60] and Federal Commitment.[61] Orthodox Peronism currently has its place in federal peronism, and is also characterized by rejecting the left wing of Peronism, Kirchnerism. Also some important current leaders of Peronism such as Alberto Rodriguez Saa, are classified within orthodox Justicialism.[62] FPF leader Alejandro Biondini meanwhile rejects both Kirchnerism and Menemism.[63]

References

[edit]- ^ It is part of the Peronist Movement.

- ^ a b c d Besoky, Juan Luis. Loyal and Orthodox, the Peronist right. A coalition against revolutionary? (in Spanish). Argentina. pp. https://www.ungs.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Besoki.pdf.

- ^ Bonavena, Pablo Augusto (UBA / UNLP). (2007). La ofensiva de Perón y la ortodoxia sindical contra los gobernadores de la Tendencia: notas sobre los casos de San Luis y Catamarca. XI Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Universidad de Tucumán, San Miguel de Tucumán.

- ^ Gerchunoff, Pablo; Llach, Lucas (2003). El ciclo de la ilusión y el desencanto: un siglo de políticas económicas argentinas (in Spanish). Ariel. ISBN 9789509122796. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2010). "La revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición: órgano de expresión de la extrema derecha". Conflicto Social (in Spanish). 3 (3): 7–28. ISSN 1852-2262. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

"Será a través de la consolidación del revisionismo histórico luego del ’55 que se irán tejiendo vínculos cada vez más sólidos entre el peronismo y el nacionalismo. Si bien ya existía alguna relación con el gobierno peronista, sabemos que éste nunca fue revisionista en su lectura de la historia y que incluso la presencia de nacionalistas en el gobierno distó de ser hegemónica. Será recién a partir del ’55 en el marco de la resistencia y a través del nacionalismo histórico que podremos ver la conformación de manera muy embrionaria de un peronismo ortodoxo." - ^ Alonso, Dalmiro (2012). "Ideología y violencia organizada en la Argentina en los años de la Guerra Fría". repositoriosdigitales.mincyt.gob.ar. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

"Para definir al peronismo ortodoxo, se parte del conglomerado de agrupaciones y tendencias que, ya sea teniendo su origen en el propio movimiento peronista o fuera de él, construyeron a partir de su experiencia social una concepción de la ideología peronista rescatando, alimentando y potenciando los rasgos más conservadores de la misma." - ^ "PROVINCIAL CONFLICTS BETWEEN THE TREND AND ORTHODOXY. La Rioja, a case study". www.google.com. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

«It was another significant expression that designated all those actors located in the so-called Peronist right; but that, ultimately, went beyond it since it could also include the centrist or moderate sectors of Peronism. It was neither more nor less than his quintessential opponent: the Peronist Orthodoxy.» - ^ Carta politica (in Spanish). Sociedad Anonima Editora Sarmiento. June 1974. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Ollier, María Matilde (2005). Golpe o revolución: la violencia legitimada, Argentina, 1966-1973 (in Spanish). EDUNTREF, Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero. ISBN 978-987-1172-08-5.

- ^ Acuña, Marcelo Luis (1995). Alfonsín y el poder económico: el fracaso de la concertación y los pactos corporativos entre 1983 y 1989 (in Spanish). Corregidor. ISBN 978-950-05-0852-0.

- ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2023). ""Vivir como machos en un mundo de maricones". Representaciones de lo masculino y lo femenino en la derecha peronista (1943-1975)". Avances del Cesor (in Spanish). 20 (29). doi:10.35305/ac.v20i29.1885.

- ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2016). "La derecha también ríe. El humor gráfico en la revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición". Revista Tempo e Argumento (in Spanish). 8 (18): 291–316. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

"Le suman a algunos gestos y ropas de mujer para tildarlos de homosexuales [Ilustración 4] y de drogadictos [Ilustración 5]." - ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2010). "La revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición: órgano de expresión de la extrema derecha". Conflicto Social (in Spanish). 3 (3): 7–28. ISSN 1852-2262. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

"Sin embargo, no todas las teorías conspirativas son antisemitas. También entre los responsables de la conspiración figuran el capitalismo salvaje, el individualismo acérrimo y el comunismo, entre otros." - ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2010). "La revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición: órgano de expresión de la extrema derecha". Conflicto Social (in Spanish). 3 (3): 7–28. ISSN 1852-2262. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

"Sin embargo, no todas las teorías conspirativas son antisemitas. También entre los responsables de la conspiración figuran el capitalismo salvaje, el individualismo acérrimo y el comunismo, entre otros." - ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2010). "La revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición: órgano de expresión de la extrema derecha". Conflicto Social (in Spanish). 3 (3): 7–28. ISSN 1852-2262. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

"Sin embargo, no todas las teorías conspirativas son antisemitas. También entre los responsables de la conspiración figuran el capitalismo salvaje, el individualismo acérrimo y el comunismo, entre otros. Dentro de las visiones conspirativas se destaca la figura de la “sinarquía"." - ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2010). "La revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición: órgano de expresión de la extrema derecha". Conflicto Social (in Spanish). 3 (3): 7–28. ISSN 1852-2262. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

"Sin embargo, no todas las teorías conspirativas son antisemitas. También entre los responsables de la conspiración figuran el capitalismo salvaje, el individualismo acérrimo y el comunismo, entre otros. Dentro de las visiones conspirativas se destaca la figura de la “sinarquía"." - ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (24 May 2013). "La derecha peronista en perspectiva". Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. Nouveaux Mondes Mondes Nouveaux – Novo Mundo Mundos Novos – New World New Worlds (in Spanish). doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.65374. hdl:11336/4140. ISSN 1626-0252. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

"…hasta llegar a las expresiones más furibundamente antimarxistas y antisemitas de la extrema derecha." - ^ Manero, Edgardo (2022). "El movimiento carapintada en Argentina. Las fijaciones estratégicas como condicionantes del proyecto político, rémoras de la Guerra Fría". In Frédérique Langue; María Laura Reali (eds.). Las ideologías de la nación. Memorias, conflictos y resiliencias en las Américas. Prohistoria Ediciones. pp. 141–176. ISBN 978-987-809-040-5. hal-03916621.

- ^ El Porteño (in Spanish). Artemúltiple S.A. 1985.

- ^ "Rodolfo Walsh, a palabra definitiva: Escritura e militância" (Rodolfo Walsh). Consultado el 29 de marzo de 2023.«Las escenas del alboroto de las masas en la mira de la voluntad fascista de estas alas del peronismo ortodoxo.»

- ^ a b c Berlochi, Ezequiel (2 July 2018). "El entramado represivo durante el tercer peronismo (1973-1976).: Entre el sentido común y las nuevas aproximaciones analíticas". Perspectivas Revista de Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish). 3 (5): 98–111. doi:10.35305/prcs.v0i5.216. ISSN 2525-1112.

- ^ Zicarelli, Álvaro (1 June 2022). Cómo derrotar al neoprogresismo: Una batalla política (in Spanish). SUDAMERICANA. ISBN 978-950-07-6727-9.

- ^ a b Ladeuix, Juan I. Perón o Muerte en la Aldea: Las formas de la violencia política en espacios locales del interior bonaerense. 1973-1976 (PhD thesis). Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata.

- ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (2010). "La revista El Caudillo de la Tercera Posición: órgano de expresión de la extrema derecha". Conflicto Social (in Spanish). 3 (3): 7–28. ISSN 1852-2262.

- ^ a b Besoky, Juan Luis (2012). An approach to the Peronist right 1973–1976 (in Spanish). pp. http://redesperonismo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/015.pdf.

- ^ Alonso, Dalmiro (2012). "Ideología y violencia organizada en la Argentina en los años de la Guerra Fría". repositoriosdigitales.mincyt.gob.ar. Retrieved 9 December 2023.«Finalmente, en julio de 1975, se produjo la principal escisión en el seno del peronismo antizquierdista que opuso a la derecha moderada que controlaba las 62 organizaciones de la C.G.T. a los ultraderechistas dirigidos por López Rega.»

- ^ "PROVINCIAL CONFLICTS BETWEEN THE TREND AND ORTHODOXY. La Rioja, a case study". www.google.com. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

It was another significant expression that designated all those actors located in the so-called Peronist right; but that, ultimately, went beyond it since it could also include the centrist or moderate sectors of Peronism. It was neither more nor less than his quintessential opponent: the Peronist Orthodoxy. - ^ Besoky, Juan Luis. Loyal and Orthodox, the Peronist right. A coalition against revolutionary? (in Spanish). Argentina. pp. https://www.ungs.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Besoki.pdf.

Not all the Peronist organizations that were critical of the left can be encompassed within the right, such as the case of Guardia de Hierro, which later became the Unique Organization for Generational Transfer (OUTG). Taking into account the work carried out on this organization by Tarruella (2005), Anchou and Bartoletti (2008) and Cucchetti (2010), among others, it would be pertinent to place it in the political center, at a more or less equidistant distance (depending on the moment) from the right and left of Peronism. In this case it would be more appropriate to locate them within the field of orthodox Peronism but not of the right. - ^ Corigliano, Francisco (2007). "Colapso estatal y política exterior: el caso de la Argentina (des)gobernada por Isabel Perón (1974-1976)". Revista SAAP: Sociedad Argentina de Análisis Político (in Spanish). 3 (1): 55–79.

- ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (5 January 2018). "Los muchachos peronistas antijudíos. A propósito del antisemitismo en el movimiento peronista". Trabajos y Comunicaciones (in Spanish) (47): e057. doi:10.24215/23468971e057. hdl:11336/86568. ISSN 2346-8971.

- ^ Murri, Lourdes. "La "Depuración" en las Universidades: Prácticas Y Discursos De la Derecha Peronista en la escala nacional y local (1974–1976)". Incihusa–Conicet.

- ^ a b Besoky, Juan Luis (24 May 2013). "La derecha peronista en perspectiva". Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. Nouveaux Mondes Mondes Nouveaux – Novo Mundo Mundos Novos – New World New Worlds (in Spanish). doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.65374. hdl:11336/4140. ISSN 1626-0252.

- ^ Schmucler, Héctor; Malecki, Sebastián; Gordillo, Mónica (13 March 2018). El obrerismo de pasado y presente: Documento para un dossier no publicado sobre (in Spanish). Eduvim. p. 214. ISBN 978-987-699-213-8.

- ^ James, Daniel (1988). Resistance and integration: Peronism and the Argentine working class, 1946-1976. Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–244. ISBN 0-521-46682-2.

- ^ Munck, Ronaldo (April 1979). "The Crisis of Late Peronism and the Working Class 1973-1976". Bulletin of the Society for Latin American Studies (30). Society for Latin American Studies (SLAS): 10–32.

- ^ Alonso, Dalmiro (2012). "Ideología y violencia organizada en la Argentina en los años de la Guerra Fría". repositoriosdigitales.mincyt.gob.ar. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b Besoky, Juan Luis (2016). "La derecha peronista: Prácticas políticas y representaciones (1943-1976)" (PDF). Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de La Plata: 22.

- ^ Munck, Ronaldo; Falcón, Ricardo [in Spanish]; Galitelli, Bernardo (1987). Argentina: From Anarchism to Peronism: Workers, Unions and Politics, 1855-1985. Zed Books. p. 192. ISBN 9780862325701.

- ^ "PROVINCIAL CONFLICTS BETWEEN THE TREND AND ORTHODOXY. La Rioja, a case study". www.google.com. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

It was another significant expression that designated all those actors located in the so-called Peronist right; but that, ultimately, went beyond it since it could also include the centrist or moderate sectors of Peronism. It was neither more nor less than his quintessential opponent: the Peronist Orthodoxy. - ^ Lapolla, Alberto Jorge (2004). Kronos: La esperanza rota, 1972-1974 (in Spanish). De la campana. ISBN 978-987-9125-54-0.

- ^ M, Pedro N. Miranda (1989). Terrorismo de estado: testimonio del horror en Chile y Argentina (in Spanish). Editorial Sextante.

- ^ Rock, David (2001). La derecha argentina: nacionalistas, neoliberales, militares y clericales (in Spanish). Javier Vergara. ISBN 978-950-15-2175-7.

- ^ "María Estela Martínez, 'Isabelita Perón'". El País (in Spanish). 14 January 2007. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ McSherry, J. Patrice (2009). Los estados depredadores: la Operación Cóndor y la guerra encubierta en América Latina (in Spanish). Lom Ediciones. ISBN 978-956-00-0062-0.

- ^ Corigliano, Francisco (2007). "Colapso estatal y política exterior: el caso de la Argentina (des)gobernada por Isabel Perón (1974-1976)". Revista SAAP: Sociedad Argentina de Análisis Político (in Spanish). 3 (1): 55–79.

- ^ LPO. "¿Rodrigazo o 2001?: Debaten los límites del ajuste económico". www.lapoliticaonline.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Alonso, Dalmiro (2012). "Ideología y violencia organizada en la Argentina en los años de la Guerra Fría". repositoriosdigitales.mincyt.gob.ar. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Besoky, Juan Luis (5 November 2013). Adiós juventud... Juan Domingo Perón y el fin de la tendencia revolucionaria. VII Jornadas de Sociología de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata (in Spanish). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación: National University of La Plata.

- ^ Bron, Florencia (6 August 2020). "Olaizola: "Cúneo no es desestabilizador; somos peronistas ortodoxos y hay cosas que no nos gustan"". DIARIO ACTUALIDAD (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Milei aspira tropa y le complica la construcción bonaerense a Pichetto". LetraP (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Guadagno, Facundo. El partido político Segunda República y Ricardo Lirio: Una mirada antropólogica sobre un nuevo nacionalismo argentino (in Spanish).

- ^ Jorquera, Miguel (15 June 2017). "Desde la izquierda hasta Biondini | Más de diez alianzas se presentarán en la provincia de Buenos Aires". PAGINA12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ pergamino.ciudad.7. "Pablo Lucidi: "Somos un grupo de vecinos con los valores ortodoxos del peronismo"". PERGAMINO CIUDAD (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Daniel Tunoni: "Dentro del peronismo ortodoxo, soy el único candidato a intendente en Mar del Plata"" (in European Spanish). 29 June 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Hugo Moyano terminó apoyando a Guillermo Moreno para presidente". www.memo.com.ar (in Spanish). 25 June 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Milei intenta revivir la alianza de Menem y Alsogaray". Nuevos Papeles (in Spanish). 10 April 2023. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023.

- ^ "José Bonacci: "Yo no sé si el pueblo sigue a Milei por su prédica liberal"". 30 May 2022.

- ^ "El peronismo a la orden del dia en las elecciones". politicaaldia.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Dante Kaplanski (12 August 2023). "Trans, escritores, nacionalistas, liberales y piqueteros: quién es quién entre los candidatos a presidente menos conocidos".

- ^ "El peronismo a la orden del dia en las elecciones". politicaaldia.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ Ostiguy, Pierre; Schneider, Aaron (May 2016). "The Politics of Incorporation: Party Systems, Political Leaders and the State in Argentina and Brazil". Researchgate. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3019.0969.

- ^ ABDO, GERARDO DAVID OMAR (13 November 2014). "Peronismo Federal: ambicion y despretigio hechos fuerza politica". Monografias.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Alejandro Biondini en Bahía: "Como decía Perón, soy un león herbívoro"". La Nueva (in Spanish). 2 September 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- Anti-communism in Argentina

- Counterterrorism in Argentina

- Conservatism in Argentina

- Dirty War

- Fascism in Argentina

- History of Argentina (1973–1976)

- National Reorganization Process

- Paramilitary organisations based in Argentina

- Peronism

- Political movements in Argentina

- Political repression in Argentina

- Terrorism in Argentina