Northern front, East Africa, 1940

| Northern front, East Africa, 1940 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of East African Campaign (World War II) | |||||||

Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana) 1940 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William Platt | Luigi Frusci | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Sudan Defence Force Northern Rhodesia Regiment | Comando Forze Armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana | ||||||

Operations on the Northern front, East Africa, 1940 in the Second World War, were conducted by the British in Sudan and the Armed Forces Command of Italian East Africa (Comando Forze Armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana) in Eritrea and Ethiopia. On 1 June 1940, Amedeo, Duke of Aosta the Viceroy and Governor-General of the Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI, Italian East Africa), commander in chief of the Armed Forces Command of the Royal Italian Army (Regio Esercito) and General of the Air Force (Generale d'Armata Aerea), had about 290,476 local and metropolitan troops (including naval and air force personnel) and by 1 August, mobilisation had increased the number to 371,053 troops. General Archibald Wavell, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of Middle East Command, had about 86,000 troops at his disposal for Libya, Iraq, Syria, Iran and East Africa. About 36,000 troops were in Egypt and 27,500 men were training in Palestine.

Hostilities began soon after the Italian declaration of war on 10 June 1940. On the Sudan–Eritrea and Sudan–Ethiopia borders, the Italian army captured Kassala, on 4 July, then Gallabat; Karora was occupied unopposed and Kurmuk taken on 7 July. The possibility of an Italian advance on Khartoum led the British to adopt a delaying strategy but apart from some local advances, the Italians fortified Kassala and Gallabat and made no offensive move. In August the Italians invaded British Somaliland and the British made a slow retreat to the coast then embarked for Aden, at some cost to the reputation of Wavell with the Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The British reversed their recognition of the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936) in favour of Haile Selassie, the deposed emperor. Mission 101 and Gideon Force were based in Sudan to conduct sabotage and subversion in the western Ethiopian province of Gojjam. After an abortive counter-attack at Gallabat in November, the British conducted patrols and raids against the Italians with Gazelle Force in the Mareb River/Gash River delta north of Kassala and bluffed their opponents into believing that the British had much larger forces in eastern Sudan.

The British blockade of the AOI made Aosta reluctant to deplete stocks of fuel, ammunition and spare parts after the invasion of British Somaliland was complete. With expectations that the Germans would defeat Britain before the end of 1940 and with the need to wait for the Italian invasion of Egypt (9–16 September 1940) to succeed before invading Sudan, the Italians in the AOI waited on events. British policy was to ensure the safety of shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden and operations in East Africa were given second priority after Egypt. With reinforcements arriving from India and troops from Egypt due after Operation Compass, the British planned to invade Eritrea from Sudan on 9 February 1941. The British were forestalled by a sudden Italian retreat from Kassala on 18 January and Platt was ordered to mount a vigorous pursuit. The British invaded Eritrea and defeated the Italians at the Battle of Agordat (26–31 January 1941) which began the conquest of Eritrea; Selassie returned to Ethiopia on 20 January.

Background

[edit]Africa Orientale Italiana

[edit]

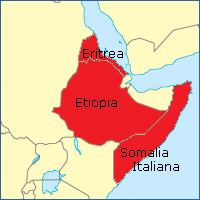

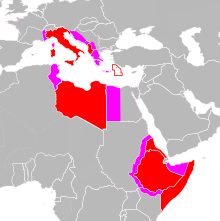

On 9 May 1936, the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, proclaimed Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI Italian East Africa), formed from the colonies of Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia, which had been occupied after the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936). Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, was appointed the Viceroy and Governor-General of the AOI in November 1937, with headquarters in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. On 1 June 1940, as the commander in chief of Comando Forze Armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East African Armed Forces Command) and Generale d'Armata Aerea (General of the Air Force), Aosta had about 290,476 local and metropolitan troops (including naval and air force personnel) in the AOI. (By 1 August, mobilisation had increased the number to 371,053 troops.)[1]

On 31 March 1940, Mussolini had laid down a defensive strategy against Kenya, a policy of limited offensives against Kassala and Gedaref (now Al Qadarif) in Sudan and a bigger offensive against French Somaliland to protect Eritrea. Naval forces based at Massawa were to take the offensive and the Regia Aeronautica would provide air support for the ground and naval operations.[2] On 10 June, Mussolini declared war on Britain and France, which made Egypt vulnerable to the forces in Italian Libya (Libia Italiana, part of Africa Settentrionale Italiana (ASI) and those in the AOI a menace to the British and French colonies in East Africa. Italian belligerence led to the closure of the Mediterranean to Allied merchant ships and endangered British supply routes along the coast of East Africa, the Gulf of Aden, Red Sea and the Suez Canal.[3][a]

Mediterranean and Middle East

[edit]In mid-1939, General Archibald Wavell was appointed General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of the new Middle East Command, over the Mediterranean and Middle East theatres.[4] Wavell had about 86,000 troops at his disposal for Libya, Iraq, Syria, Iran and East Africa, of which about 9,000 were in Sudan, 8,500 in Kenya, 1,475 in British Somaliland and 2,500 in Aden.[5][6] From 1938, Major-General William Platt had been the al-qa'id al-'amm (the Kaid, Commandant) of the Sudan Defence Force with responsibility for the defence of Sudan, which had a 1,000 mi (1,600 km) frontier with Ethiopia.[7] On 19 May 1940, the British discovered through signals intelligence that the Italian forces in the AOI had been ordered secretly to mobilise.[8] Before the declaration of war, the British detected increases in the number of Italian troops on the Sudan border and assumed that if the Italians attacked Sudan, the objectives would be the capital Khartoum, 300 mi (480 km) to the west of the Eritrean frontier, Atbara, the junction of railways to Khartoum, 200 mi (320 km) from the border and Port Sudan, the only decent port and which had the only heavy engineering workshops in the country. The ground was arid and had no all-weather roads but in the dry weather before the monsoon in June or July, the ground was motorable nearly everywhere.[7]

Ultra

[edit]The Italians in the AOI had replaced their ciphers by November 1940 but by the end of the month, the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) in England and the Cipher Bureau Middle East (CBME) in Cairo had broken the Regio Esercito and Regia Aeronautica replacement codes. Sufficient low-grade ciphers had been broken to reveal the Italian order of battle and the supply situation, by the time that the British offensive began on 19 January 1941. Italian dependence on wireless communication, using frequencies on which it was easy for the British to eavesdrop, led to a flood of information from the daily report from the Viceroy to the operational plans of the Regia Aeronautica and Regio Esercito.[9] On occasion, British commanders had messages before the recipients and it was reported later by the Deputy Director Military Intelligence in Cairo, that

...he could not believe that any army commander in the field had [ever] been better served by his intelligence....

— DDMI (ME)[9]

Prelude

[edit]Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

[edit]

In 1940, the British had three infantry battalions in Sudan and the SDF, which had 4,500 men in 21 companies, the best-equipped being Motor Machine-Gun companies, with light machine-guns mounted in vans, lorries and a few locally made armoured cars; the Sudan Horse was converting to a 3.7-inch mountain howitzer battery.[10][b] Platt held Khartoum with 2nd Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, the 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment at Atbara and the 1st Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment at Gebeit and Port Sudan. The SDF garrisoned the frontier with the provincial police and a motley group of irregular scouts, to watch, harass and delay the Italians.[11]

Should the Italians invade, the units would converge against the attackers, exploit distance, the inadequate roads, and supply difficulties, to impede their advance. The Royal Air Force (RAF) had three bomber squadrons, K Flight, 112 Squadron, with six Gladiator fighters at Port Sudan and 430 Flight, 47 Squadron for army co-operation. The aircraft were convenient for Port Sudan and the Red Sea but far from Kassala and Gedaref. In August, 203 Group RAF was formed at Khartoum, to guard the eastern end of the Takoradi air route from the Gold Coast (Ghana), with 1 (Fighter) Squadron, South African Air Force (SAAF), equipped with Gladiators.[11]

Kassala

[edit]In 1940, Kassala was a provincial town of around 25,000 inhabitants, about 20 mi (32 km) from the frontier on the Mareb River/Gash River and the Sudan Railway which looped eastwards towards the border with Ethiopia. The river rose in Eritrea and flowed, full of silt, for about three months each year, which created extremely fertile land for cotton growing; the crop being exported from the railway station outside Kassala. The Italian Via Imperiale ran from Asmara, the capital of Eritrea; after the Italians dammed the river at Tessenei to create a rival cotton growing industry and extended the road from Asmara to the Eritrea–Sudan border to transport the cotton crop, the road became an obvious route for an offensive in either direction. In July, the British found that Italian troops were assembling near Tessenei about 12 mi (19 km) inside the Eritrean border. The British planned to attack on 3 July but a wireless failure led to a postponement.[12]

At Kassala, the British had No. 5 Motor Machine-Gun Company, No. 6 Mounted Infantry Company of the Eastern Arab Corps, a mounted infantry company of the Western Arab Corps from Darfur 1,000 mi (1,600 km) away and the local police.[12] (No. 3 Motor Machine-Gun Company from Butana arrived at noon on 4 July.) After hostilities began on 10 June, the Regia Aeronautica flew reconnaissance sorties over Sudan and bombed Kassala, Port Sudan, Atbara, Kurmuk and Gedaref. Small arms were the only defence against air attack and civilian morale suffered but the bombing caused no military damage. The SDF patrolled frequently and raided across the Sudan–Ethiopia border around Kassala and Gallabat, causing some casualties and taking several prisoners. The Italian forces in the AOI remained passive in June but during July prepared to attack Karora, Kassala, Gallabat and Kurmuk.[11]

Italian preparations

[edit]

Before the Italian declaration of war, Mussolini intended a defensive strategy in the AOI, with tactical offensives to protect Eritrea by attacking French Somaliland (Djibouti) and conducting limited attacks on Sudan.[2] The Italian army in the AOI had one metropolitan division, the equivalent of two more European divisions, all short of heavy weapons and transport and seven understrength colonial divisions.[13]

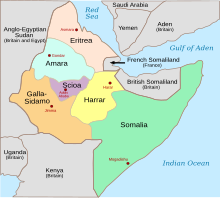

The army was organised in four commands, the Northern Sector in the vicinity of Asmara, Eritrea (Lieutenant-General Luigi Frusci, Comando Truppe dell'Eritrea of the Regio corpo truppe coloniali d'Eritrea, Governor of the Eritrea Governorate and Amhara Governorate), the Southern Sector in the Galla-Sidamo Governorate (General Pietro Gazzera), the Eastern Sector on the border with French Somaliland and British Somaliland (General Guglielmo Nasi) and the Giuba Sector (Lieutenant-General Carlo De Simone) covering southern Somalia near Kismayo, Italian Somaliland.[14]

The Regia Aeronautica had 325 aircraft in the AOI, 142 of which were in reserve (not all operational) with little prospect of more supplies of fuel, ammunition and spare parts.[2] A force was concentrated near the Sudan border for an attack on Kassala, comprising two colonial brigades, four squadrons of cavalry, approximately 24 light tanks, medium tanks and armoured cars and ten batteries of artillery.[15]

Operations

[edit]Capture of Kassala

[edit]

The attack on Kassala was led by Frusci and Major-General Vincenzo Tessitori with Italian and colonial forces comprising about 6,500 men in three columns, Gulsa east, Gulsa west, equipped with trucks and Central, with support from the Regia Aeronautica and some cavalry squadrons acting as vanguards.[16] At 3:00 a.m. on 4 July 1940, the three columns, about 19–22 mi (31–36 km) apart, started their attack on Kassala. The cavalry, led by Lieutenant Francesco Santasilia, bypassed Mount Kasala and Mount Mocram and launched the first attack.[17]

Kassala was held by less than 500 men of the SDF and local police, who remained under cover during a twelve-hour bombardment by the Regia Aeronautica and then emerged. The defenders knocked out six Italian tanks and inflicted considerable casualties on the attackers. At 1:00 p.m., Italian cavalry entered Kassala and the defenders withdrew to Butana Bridge, having lost one man killed, three wounded and 26 missing, some of whom rejoined their units.[18] Italian casualties were 43 dead and 114 men wounded.[16] Gazzera occupied the fort of Gallabat the same day and Kurmuk in Sudan. Gallabat was placed under the command of Colonel Castagnola and fortified.[19]

At Kassala, the 12th Colonial Brigade built anti-tank defences, machine-gun posts and strongpoints. The Italians were disappointed to find no strong anti-British sentiment among the Sudanese population. During the Italian attack at Kassala a battalion of Italian colonial troops and a banda (pl. irregulars) attacked Gallabat and forced No. 3 Company, Eastern Arab Corps to retire. Karora was occupied unopposed when the Sudanese police were ordered to withdraw and at Kurmuk on 7 July, another colonial battalion and a band supported by artillery and aircraft, overcame a force of 60 Sudanese police after a short engagement.[20]

The Italian attacks had gained a valuable entry point to Sudan at Kassala, made it more difficult for the British to support the indigenous resistance in Gojjam by capturing Gallabat and the loss of Kurmuk prompted some of the locals to resort to banditry. Local Sudanese opinion was impressed by the Italian successes but the population of Kassala continued to support the British and supplied valuable information during the occupation. The SDF continued to operate close to Kassala and on 5 July, a company of the 2nd Warwick arrived at Gedaref to act as a reserve for the SDF. The British discovered that rumours of the arrival of the Warwick had reached the Italians in greatly magnified form and Platt decided to bluff the Italians into believing that there were far greater forces on the Sudan border. An Italian map captured on 25 July showed around 20,000 British and Sudanese troops in Kassala province. The 5th Indian Infantry Division was ordered to Port Sudan on 2 August.[20]

Gazelle Force

[edit]In September 1940, the 5th Indian Infantry Division (Major-General Lewis Heath) began to arrive in Sudan; Platt held back the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier John Marriott) around Port Sudan and the rest, with attachments from the SDF, was ordered to prevent an Italian advance on Khartoum, from Goz Regeb on the Atbara River to Gallabat, a front of about 200 mi (320 km). Gazelle Force (Colonel Frank Messervy), based on Skinner's Horse, No. 1 Motor Machine-Gun Group of the SDF and a varying amount of field and horse artillery, was assembled near Kassala to probe forwards, to harass the Italians and keep them off-balance to make an impression of a much larger force and encourage a defensive mentality. By using the term Five instead of 5th in all communications, the British managed to persuade Italian military intelligence that five Indian divisions occupied the 5th Indian Division area. In November, after the failed British attack at Gallabat, Gazelle Force operated from the Gash river delta against Italian advanced posts around Kassala on the Ethiopian plateau, to the extent that Aosta ordered Frusci, the commander of the Northern Sector to challenge the British raiders. Two Italian battalions conducted desultory operations against Gazelle Force 30 mi (48 km) north of Kassala for about two weeks, then withdrew.[21]

In Rome, General Ugo Cavallero, the new Chief of the Defence Staff (Capo di Stato Maggiore Generale, had urged the abandonment of plans to invade Sudan and to concentrate on the defence of the AOI.[22] From early January, signs appeared that the Italians were reducing the number of troops on the Sudan frontier and a withdrawal from Kassala seemed possible.[23] News of the Italian disaster in Operation Compass in Egypt, hit-and-run attacks by Gazelle Force and the activities of Mission 101 in Ethiopia, led Frusci to become apprehensive about the northern route to Kassala. On 31 December, the troops on the northern flank withdrew behind Sabdaret, with patrols forward at Serobatib and Adardet and a mobile column in Sabdaret for contingencies. Frusci was ordered to retire from Kassala and Metemma to the passes from Agordat to Gondar but objected on grounds of prestige and proclaimed that the imminent British attack would be scattered. On 17 January, the 12th Colonial Brigade withdrew from Kassala and Tessenei to the triangle formed by the northern and southern roads from Kassala at Keru, Giamal Biscia and Aicota.[24]

British Somaliland, 1940

[edit]

In 1940, British Somaliland was garrisoned by 631 members of the Somaliland Camel Corps (SCC) and a small party of police at Berbera armed only with small-arms and anti-tank rifles with 29 motor vehicles, 122 horses and 244 camels but by mid-July, reinforcements of two infantry battalions had arrived.[25] The British hoped that the effort of invading British Somaliland would act as a deterrent and that the French in Djibouti would be a more tempting target. The defeat in France in 1940 and the French armistices with Germany and Italy left the British in Somaliland isolated. On 3 August 1940, the Italians invaded with two colonial brigades, four cavalry squadrons, 24 M11/39 medium tanks and L3/35 tankettes, several armoured cars, 21 howitzer batteries, pack artillery and air support.[26]

The SCC skirmished with the advancing Italians as the main British force slowly retired. On 11 August, Major-General Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen took command as reinforcements increased the British garrison to five battalions with about 4,500 British and Commonwealth troops, 75 per cent being African infantry and Somali irregulars.[27] The main British defensive position was at the Tug Argan Gap, which commanded the road to Berbera and on 11 August, the Battle of Tug Argan began.[28] By 14 August, the British were close to being cut off and with only one battalion left in reserve and next day, Godwin-Austen received permission to withdraw from the colony. By on 18 August, most of the British and local troops had been evacuated to Aden and the Italians entered Berbera on the evening of 19 August.[29] The British had 38 fatal casualties and 222 wounded; the Italians suffered 2,052 casualties and consumed irreplaceable resources.[30] Churchill criticised Wavell for abandoning the colony but Wavell called Godwin-Austen's retirement a textbook withdrawal in the face of superior numbers.[31]

Capture of Gallabat

[edit]

Gallabat fort lay in Sudan about 200 mi (320 km) south of Kassala opposite Metemma over the Ethiopian border beyond the Boundary Khor, a dry riverbed with steep banks covered by long grass. British orders forbade firing across the frontier if war was declared but the platoon in Gallabat heard over the wireless that it had begun and fired 13,000 rounds from a ridge overlooking Metemma.[32][c] Both places were surrounded by field fortifications and Gallabat was held by a colonial infantry battalion. Metemma had two colonial battalions and a band formation, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Castagnola. The 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, a field artillery regiment, B Squadron, 6th RTR with six Cruiser tanks and six Light Tank Mk VI, attacked Gallabat on 6 November at 5:30 a.m.[33]

An RAF contingent of six Wellesley bombers and nine Gladiator fighters were thought sufficient to overcome the 17 Italian fighters and 32 bombers believed to be in range.[33] The infantry assembled 1–2 mi (1.6–3.2 km) from Gallabat, whose garrison was unaware that an attack was coming, until the RAF bombed the fort and put the wireless out of action. The field artillery began a simultaneous bombardment, changed target after an hour and bombarded Metemma. The night previous, the 4th Battalion, 10th Baluch Regiment occupied a hill overlooking the fort as a flank guard. The troops on the hill covered the advance at 6:40 a.m. of the 3rd Royal Garwhal Rifles followed by the tanks. The Indians reached Gallabat and fought hand-to-hand with "Granatieri di Savoia" Division and some Eritrean troops in the fort.[34]

At 8:00 a.m. the 25th and 77th Colonial battalions counter-attacked and were repulsed but three British tanks were knocked out by mines and six by mechanical failures caused by the rocky ground.[34] The defenders at Boundary Khor were dug in behind fields of barbed wire and Castagnola contacted Gondar for air support. Italian bombers and fighters attacked all day, shot down seven Gladiators for a loss of five Fiat CR-42 fighters and destroyed the lorry carrying spare parts for the tanks. The ground was too hard and rocky to dig trenches and when Italian bombers made their biggest attack, the infantry had no cover. An ammunition lorry was set on fire by burning grass and the sound was taken to be an Italian counter-attack from behind; when a platoon advanced towards the sound with fixed bayonets, some troops thought that they were retreating.[35]

Part of the 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment at the fort broke and ran, carrying some of the Gahrwalis with them. Many of the British fugitives mounted their transport and drove off, spreading the panic and some of the runaways reached Doka before being stopped.[34] (The battalion was eventually replaced by the 2nd Highland Light Infantry and fought in Syria and Iraq.)[34] The Italian bombers returned next morning and that evening, Slim ordered a withdrawal from Gallabat Ridge 3 mi (4.8 km) westwards to less exposed ground. Sappers from the 21st Field Company remained behind to demolish the remaining buildings and stores in the fort. The artillery bombarded Gallabat and Metemma and set off Italian ammunition dumps. British casualties since 6 November were 42 men killed and 125 wounded.[36] The Italian 27th Colonial Battalion was thought to have been destroyed with 600 killed or wounded.[37]

The brigade patrolled to deny the fort to the Italians and on 9 November, two Baluch companies attacked, held the fort during the day and retired in the evening. During the night, an Italian counter-attack was repulsed by artillery-fire and next morning the British re-occupied the fort unopposed. Ambushes were laid and prevented Italian reinforcements from occupying the fort or the hills on the flanks, despite frequent bombing by the Regia Aeronautica.[35] The brigade re-occupied the ridge three days later but made no attack on Metemma.[38] The caravan routes into Ethiopia needed to supply the Arbegnoch ("Patriots", Ethiopian irregulars supported by the British) and by Gideon Force remained under Italian control. For two months, the 10th Indian Brigade and then the 9th Indian Brigade simulated a division, the slouch hats of The Garhwal Rifles being taken as a sign that an Australian division had arrived.[39] The brigades blazed communication trails eastwards 80 mi (130 km) from Gedaref and created dummy airfields and stores depots, to convince Italian military intelligence that the British offensive from Sudan would be towards Gondar in the south and that the attack at Kassala into Eritrea was a bluff.[40]

Aftermath

[edit]Analysis

[edit]

July was the height of the rainy season but they were unusually light and disrupted road travel far less than usual. The Italians made no attempt to exploit the victory at Kassala, apart from a short advance to Adardeb near the railway; Kurmuk was abandoned at the same time. The Italians might have believed that an advance would be too difficult or overestimated the size of the forces opposite them. The British to the north and west had time to plan their delaying campaign against an advance on Khartoum, Atbara or Port Sudan. When no attack came, parties from the Worcester and Essex reinforced the force outside Kassala which induced the Italians to retreat into the town and wait. The British issued an intelligence summary on 18 July, which described the huge advantage in numbers enjoyed by the Italians and the apparent absence of any intention decisively to use it. The attack on Kassala was called a raid and the other attacks a nuisance.[41]

The report concluded that the Italians were waiting on the conclusion of armistice talks with the Vichy regime in France before deciding on strategy. The British concluded that the small British and colonial contingents in East Africa had succeeded in defending the frontiers of the east African colonies, according to the strategy laid down by Wavell.[41] The British evacuation of Somaliland was announced on 20 August and Home Intelligence Reports showed that after a period of public apathy there was increasing criticism and doubts about the official excuses being made and scepticism that the reverse did not matter. After the occupation of the Channel Islands and apprehension over the course of the Battle of Britain the news added to public disquiet. While British press reports that the Italian forces in the AOI were a "...beleaguered army which must live on its reserves...." were the same as the Italian appreciation of the situation, this was not publicly known. A member of the public remarked that

We should have recognised the danger signals, first silence, then inadequate news, then hints that the place wasn't worth defending, then the successful strategic withdrawal.

— Anon, 20 August 1940[42]

Some senior British officials thought that defeat was inevitable and that it was a Pyrrhic victory for the Italians, who had used irreplaceable resources, increased the dispersion of the military forces in the AOI and lost the means to follow alternatives, which might have brought more success.[43]

The British had established the Italian order of battle and aspects of Italian strategic thinking but the Italians managed to keep their tactical moves secret. The Italian army changed its cyphers on the outbreak of war and the British took until November to break into the new cypher; a new Regia Aeronautica cypher was introduced in November but this was quickly broken. During the signals intelligence blackout, the British lacked knowledge of the Italian order of battle, equipment and readiness; fears grew that the Italians were preparing to invade Sudan and Kenya. When the British counter-offensives began in January 1941, documents captured by the British and the isolation of the Italians in East Africa made it impossible for them to change their cyphers for transmissions to Italy, created perfect conditions for "the cryptographers' war". Despite a lack of aircraft for reconnaissance and no network of spies in the AOI, the British in 1941 had a comprehensive view of the Italian supply situation and every Italian decision. Knowledge that the Italians were going to retire from Kassala, prompted the British to begin their invasion of the AOI on 19 January instead of 8 February, eavesdropping on Italian plans and assessments of the situation, often before the recipients had decoded the signals.[44]

While in London for discussions with Churchill, Wavell signalled to Cairo that the evacuation of British Somaliland had not been the cause of recriminations but after more details of the Battle of Tug Argan arrived in London, Churchill questioned why the British had retreated and if the Italian superiority was really overwhelming, why they had not exploited their advantage. Churchill complained that the defence of the Tug Argan Gap had been "precipitately discontinued" and that Godwin-Austen had exaggerated the number of British casualties. Churchill blamed the local commanders for failing adequately to conduct a fighting retreat. Wavell replied that high casualties were not a sign of good leadership; Churchill never forgave the slight and began to plan his dismissal. Aosta later wrote that the invasion plan depended on speed but supply difficulties, unexpectedly poor weather and rains blocked some roads, slowing the advance. During the delay caused by the British defence of Tug Argan, Aosta tried to send a force of 300 volunteers by aircraft to capture Berbera by coup de main but the scheme was cancelled, because the British remained in occupation of the only landing ground. The Italians had failed to exploit the opportunity and given the haphazard nature of the British evacuation and the lack of defences, the withdrawal might have prevented.[45]

Aosta drew up plans to exploit the victory in Somaliland, including a scheme to invade Kenya with two columns, to rendezvous at Fort hall north of Nairobi, ready to capture the capital. Under the text Aosta wrote, "Extreme caution must be observed". In Eritrea, Tessitore had proposed to invade Sudan soon after the declaration of war and capture Khartoum and Atbara. On orders from Rome, Aosta based his strategy on events further north in Libya and Egypt. After the Italian invasion of Egypt, Aosta considered that an offensive move was dependent on being able to link with the forces of Italian Libya, which became impossible after the British expelled the Italians from Egypt in Operation Compass (9 December 1940 – 9 February 1941). Aosta liaised with Marshal Rodolfo Graziani in Libya but as Italian supplies of fuel in the AOI diminished, passive defence became the only realistic choice. In late 1940, Aosta was advised that the war in Europe would probably end in October and decided to wait on events.[46]

Casualties

[edit]At Kassala, the British lost one man killed, three wounded and 26 missing, some of whom rejoined their units.[18] the Italians suffered casualties of 43 dead and 114 men wounded.[16] During the invasion of British Somaliland, the British suffered casualties of 38 killed and 222 wounded, mostly troops of the Northern Rhodesia Regiment and the Camel Corps machine-gunners, along with some equipment that could not be embarked during the evacuation. The Italians suffered 2,052 casualties and expended irreplaceable fuel and ammunition. In the fighting at Gallabat from 6 November, the British suffered casualties of 42 men killed and 125 wounded. Italian losses were thought to be around 600 men.[47]

Subsequent operations

[edit]

After the British reverse at Gallabat in November, Wavell held a review of the situation in Cairo from 1 to 2 December. With Operation Compass imminent in Egypt, the British forces in east Africa were to provide help to the Patriots in Ethiopia and continue to pressure the Italians at Gallabat. Kassala was to be recaptured early in January 1941, to prevent an Italian invasion and the 4th Indian Division was to be transferred from Egypt to Sudan from the end of December. With the success of Compass, east Africa was made second priority after Egypt and it was intended to have defeated the Italian forces in Ethiopia by April. The Italian retirement from Kassala on 18 January 1941, suggested that the British victory in Egypt was affecting the situation in East Africa and that a bolder British strategy was justified. The British offensive from Sudan due on 9 February was brought forward to 19 January.[48]

Platt was ordered to mount a vigorous pursuit and fought the Battle of Agordat from 26 to 31 January 1941, leading to the capture of Agordat on 1 February and Barentu the next day. Haile Selassie, the deposed Emperor of Ethiopia, crossed into Ethiopia on 20 January and in February, the Frontier Battalion SDF, the 2nd Ethiopian Battalion and Nos 1 and 2 Operational Centres, were renamed Gideon Force. Lieutenant-Colonel Orde Wingate was ordered to capture Dangila and Bure, which had garrisons of a colonial brigade each and gain control of the road between Bure and Bahrdar Giorgis, to provide a base for Selassie. The Arbegnoch were to attack the main roads from Gondar and Addis Ababa and keep as many Italian troops back defending Addis Ababa as possible.[49]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Kingdom of Egypt remained neutral during the Second World War but the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 allowed the British to occupy Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[3]

- ^ The SDF comprised the Camel Corps, Eastern Arab Corps, Western Arab Corps and the Equatorial Corps.[10]

- ^ The party had conducted the first hostile act of the East African Campaign and after informing them that the act was against orders, the officer commanding had the event written off as training.[32]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 2, 93.

- ^ a b c Butler 1971, p. 298.

- ^ a b Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 6–7, 69.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 19, 93.

- ^ Dear 2005, p. 245.

- ^ Raugh 1993, p. 64.

- ^ a b Playfair et al. 1957, p. 168.

- ^ Hinsley 1979, p. 202.

- ^ a b Hinsley 1994, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Playfair et al. 1957, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b Stewart 2016, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Butler 1971, p. 297.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Raugh 1993, p. 72.

- ^ Del Boca 1986, p. 356.

- ^ a b Maioli & Baudin 1974, p. 134; Stewart 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 170–171; Schreiber, Stegemann & Vogel 1995, p. 295.

- ^ a b Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Raugh 1993, pp. 172–174.

- ^ Mackenzie 1951, p. 42.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 397, 399.

- ^ Raugh 1993, pp. 172–174, 175; Mackenzie 1951, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Stewart 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Mackenzie 1951, p. 23; Playfair et al. 1957, p. 170.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Stewart 2016, p. 72.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 172–177.

- ^ Raugh 1993, p. 82.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, p. 178.

- ^ a b Stewart 2016, p. 58.

- ^ a b Playfair et al. 1957, p. 398.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie 1951, p. 33.

- ^ a b Brett-James 1951, ch 2.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, p. 399.

- ^ Stewart 2016, p. 115.

- ^ Mackenzie 1951, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Mackenzie 1951, p. 34.

- ^ Mackenzie 1951, p. 43.

- ^ a b Stewart 2016, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Stewart 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Stewart 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Hinsley 1979, pp. 380–381.

- ^ Stewart 2016, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Stewart 2016, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 178, 399; Raugh 1993, p. 82; Stewart 2016, p. 115.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 400.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1957, pp. 405–406; Raugh 1993, pp. 175, 177.

References

[edit]- Brett-James, Antony (1951). Ball of Fire – The Fifth Indian Division in the Second World War. Aldershot: Gale & Polden. OCLC 4275700.

- Butler, J. R. M. (1971) [1957]. Grand Strategy: September 1939 – June 1941. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II (2nd, rev. ed.). HMSO. ISBN 0-11630-095-7.

- Dear, I. C. B. (2005) [1995]. Foot, M. R. D. (ed.). Oxford Companion to World War II. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280670-3.

- Del Boca, Angelo (1986). Italiani in Africa Orientale: La caduta dell'Impero [Italians in East Africa: The Fall of the Empire] (in Italian). Vol. III. Roma-Bari: Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-2810-9.

- Hinsley, F. H.; et al. (1979). British Intelligence in the Second World War. Its influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War. Vol. I. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630933-4.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations (abridged edition). History of the Second World War (2nd rev. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic: September 1939 – March 1943 Defence. Vol. I. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 59637091.

- Maioli, G.; Baudin, J. (1974). Vita e morte del soldato italiano nella guerra senza fortuna: La strana guerra dei quindici giorni [Life and Death of Italian Soldiers in the War with no Luck: The Strange War of Fifteen Days]. Amici della storia. Vol. I. 18 volumes, 1973–1974. Ginevra: Ed. Ferni. OCLC 716194871.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (1957) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (4th ed.). HMSO. OCLC 494123451. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Raugh, H. E. (1993). Wavell in the Middle East, 1939–1941: A Study in Generalship (1st ed.). London: Brassey's UK. ISBN 978-0-08-040983-2.

- Schreiber, G.; Stegemann, B.; Vogel, D. (1995). Falla, P. S. (ed.). The Mediterranean, South-East Europe and North Africa, 1939–1941: From Italy's Declaration of non-Belligerence to the Entry of the United States into the War. Germany and the Second World War. Vol. III. Translated by McMurry, D. S.; Osers, E.; Willmot, L. (trans. Oxford University Press, London ed.). Freiburg im Breisgau: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt. ISBN 978-0-19-822884-4.

- Stewart, A. (2016). The First Victory: The Second World War and the East Africa Campaign (1st ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20855-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Mockler, A. (1987) [1984]. Haile Selassie's War (2nd. pbk. Grafton Books [Collins], London ed.). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-586-07204-7.

- Petacco, Arrigo (2003). Faccetta nera: storia della conquista dell'impero [Black Face: History of the Conquest of the Empire]. Le scie. Milano: Edizioni Mondadori. ISBN 978-8-80451-803-7.

External links

[edit]- Conflicts in 1940

- Conflicts in 1941

- Land battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Battles and operations of World War II involving Italy

- Eritrea–Sudan border

- Ethiopia–Sudan border

- East African campaign (World War II)

- Eritrea in World War II

- Ethiopia in World War II

- Military history of Sudan

- Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

- 1940 in Ethiopia

- 1941 in Ethiopia

- 1940s in Sudan

- 1940s in Eritrea