United Kingdom home front during World War II

| WW2 Britain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 September 1939 – 8 May 1945 | |||

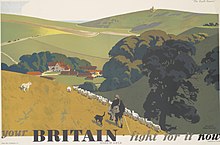

One of a series of posters by Frank Newbould, intended to arouse patriotic feelings for an idealised pastoral Britain. | |||

| Monarch(s) | George VI | ||

| Leader(s) | |||

Chronology

| |||

| Periods in English history |

|---|

| Timeline |

The United Kingdom home front during World War II covers the political, social and economic history during 1939–1945.

The war was expensive and financed through high taxes, selling off assets, and accepting large amounts of Lend Lease from the US and Canada. The US provided $30 billion in munitions, while Canada also contributed aid. American and Canadian aid did not have to be repaid, but there were also American loans that were repaid.[1]

Britain's total mobilisation during this period proved successful in winning the war by maintaining strong public support. The media dubbed it a "people's war," which caught on and signified the popular demand for planning and an expanded welfare state.[2][3] By 1945, the Post-war consensus emerged, delivering a welfare state.[4] The Royal family played major symbolic roles during the war. They refused to leave London during the Blitz and visited troops, munition factories, dockyards, and hospitals all over the country.[5]

The British relied successfully on voluntary labour. Munitions production rose dramatically while maintaining high quality. Food production was emphasised to free shipping for munitions. Farmers increased the area under cultivation from 12 million to 18 million acres (from about 50,000 to 75,000 km2), and the farm labour force expanded by a fifth, thanks to the Women's Land Army.[6]

Politics

[edit]Planning the welfare state

[edit]The common experience of wartime hardships created a new consensus for a post-war welfare state, including universal social security, a free national health service, improved secondary education, expanded housing, and family allowances.[7][8][9] The success of the wartime government in providing new services, such as hospitals and school lunches, and the prevailing egalitarian spirit contributed to widespread support for an enlarged welfare state, supported by all major parties. Welfare conditions, particularly regarding food, improved during the war as the government imposed rationing and subsidised food prices. However, housing conditions worsened due to bombing, and clothing was in short supply. Equality increased dramatically as incomes declined sharply for the wealthy and white-collar workers due to soaring taxes, while blue-collar workers benefited from rationing and price controls.[10]

People demanded an expansion of the welfare state as a reward for their wartime sacrifices. The Labour Party took the initiative, but the Conservatives led the Education Act of 1944, which made major improvements in secondary schools in England and Wales.[11] Historians consider it a "triumph for progressive reform," and it became a core element of the Post-war consensus supported by all major parties.[12]

William Beveridge of the Liberal Party declared war on the five "giant evils" of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness. He recommended systematising and universalising various income maintenance services. Unemployment and sickness benefits were to be universal, with new benefits for maternity. The old-age pension system would be revised and expanded, requiring retirement. A full-scale National Health Service would provide free medical care for everyone. All major parties endorsed these principles, largely put into effect when peace returned.[13]

Planning for postwar housing began in 1941. Conservatives argued that wider ownership of property would give people a real economic stake in society. After 1945, expanding ownership became the signature Conservative issue, while Labour still deprecated private ownership.[14] All parties wanted to stimulate the construction industry. The consensus policy was that local authorities would lead during the transitional period, but in the longer run, most new building would be left to the private sector. Local government would concentrate on slum clearance and provision for the least well off. Financial stringencies in the late 1940s postponed the ideal plan into the 1950s.[15][16]

Economics

[edit]

The scale of mobilisation for war is best measured by the proportion of GDP devoted to the war effort, which was 7.4% in 1938, 15.3% in 1939, 43.8% in 1940, 52.7% in 1941, 55.3% in 1943 (peaked figure) and 53.4% in 1944.[17] The wartime net losses in British national wealth amounted to 18.6% (£4.595 billion) of the pre-war wealth (£24.68 billion), at 1938 prices.[18]

Finance

[edit]In six years of war, there was a net inflow of £10 billion. Of this £1.1 billion came from the sale of investments; £3.5 billion was made up of new borrowing, of which £2.7 billion was contributed by the Empire's Sterling Area.[19] Canada made C$3 billion in gifts and loans on easy terms. Above all came the American money, and loans and Lend Lease grants of £5.4 billion. This funded heavy purchases of munitions, food, oil, machinery and raw materials. There was no charge for Lend Lease supplies delivered during the war. There was a charge for supplies delivered after September 2, 1945. Britain's borrowing from India and other countries measured by "sterling balances" amounted to £3.4 billion in 1945. Britain treated this as a long-term loan with no interest and no specified repayment date. The British treasury was nearly empty by 1945.[20]

When the war began Britain imposed exchange controls. The British Government used its gold reserves and dollar reserves to pay for munitions, oil, raw materials and machinery, mostly from the U.S. By the third quarter of 1940 the volume of British exports was down 37% compared to 1935. Although the British Government had committed itself to nearly $10,000 million of orders from America, Britain's gold and dollar reserves were near exhaustion. The Roosevelt Administration was committed to large-scale economic support of Britain and in March 1941 began Lend-Lease, whereby America would give Britain supplies totalling $31.4 billion which did not have to be repaid.[21]

The government and the public opinion in the early months were preoccupied with inflationary dangers.[22] In the end the government did a reasonable job in lowering the rising cost of living index.[22]

Industry

[edit]

When war broke out in 1939, Great Britain, as an island nation, was dependent on goods imported by sea for many of its supplies. The days of significant air cargo traffic had yet to arrive but would have been equally vulnerable to enemy attack. Although the term was not used in those days, there was an immediate recourse to recycling to conserve scarce resources. Garden railings were removed for their scrap metal and aluminium kitchen saucepans were collected for their potential in the aircraft industry. Whilst there may have been undue optimism of some of the benefits, nevertheless, the whole population was involved in a practical way in contributing to the war effort.[23]

David Edgerton has emphasised the success story in producing munitions at home and using the Empire and the U.S. to build a very large high quality stock of weapons.[24] Industrial production was reoriented toward munitions, and output soared. In steel, for example, the Materials Committee of the government tried to balance the needs of civilian departments and the War Department, but strategic considerations received precedence over any other need.[25] Highest priority went to aircraft production as the RAF was under continuous heavy German pressure. The government decided to concentrate on only five types of aircraft in order to optimise output. They received extraordinary priority. Covering the supply of materials and equipment and even made it possible to divert from other types the necessary parts, equipment, materials and manufacturing resources. Labour was moved from other aircraft work to factories engaged on the specified types. Cost was not an object. The delivery of new fighters rose from 256 in April to 467 in September 1940—more than enough to cover the losses—and Fighter Command emerged triumphantly from the Battle of Britain in October with more aircraft than it had possessed at the beginning.[26] Starting in 1941 the U.S. provided munitions through Lend lease that totalled $15.5 billion[27]

Rural economies

[edit]Before the war Britain imported 70% of its food. Home agricultural production increased 35% during the war. In terms of calories, domestic output nearly doubled. Together with imports and rationing, this meant the British were well-fed, they ate less meat (down 36% by 1943) and more wheat (up 81%) and potatoes (up 96%).[28][29] Farmers increased the number of acres under cultivation from 12,000,000 to 18,000,000 (from about 50,000 to 75,000 km2), and the farm labour force was expanded by a fifth, thanks especially to the Women's Land Army.[30] Farm women had expanded duties, with the young men absent at war. They were helped by prisoners of war from Italy and Germany. The Women's Land Army recruited tens of thousands of young women from urban areas for paid labour on farms that needed them, at about 30 shillings a week. Wages for available male farmworkers trebled during the war to £3 a week.[31]

One new speciality was harvesting timber, for which the government set up the Women's Timber Corps, a branch of the Women's Land Army that operated 1942-46.[32]

For city and urban residents, the government promoted Victory Gardens that grew vegetables, fruits, and herbs. About 1.4 million allotments were made; they took some of the pressure off the food rationing system and boosted civilian morale.[33] Franklin Ginn peels away complex layers of meaning beyond growing some food. Participants were not randomly digging; they were promoting self-sufficiency, imposing control over the domestic sphere, and exhibiting patriotism in working for the common good of winning the war. There were sharply different gender roles and class experiences; gardening had been a favourite elite hobby and the upper-class women helping out knew what they were doing. The much touted statistics of additional food production were designed to foster general confidence in the progress of the war, not just the progress of plants.[34]

Rationing

[edit]

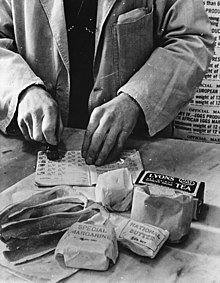

Rationing was designed to provide minimum standards of essential consumption for the entire population, to reduce waste, to reduce trans-Atlantic shipping usage (and so free up shipping for war materiel), and to make possible the production of more war supplies with less variety. The theme of equality of sacrifice was paramount.[35]

Just before the war began Britain was importing 20,000,000 long tons of food per year, including about 70% of its cheese and sugar, nearly 80% of fruits and about 70% of cereals and fats. The UK also imported more than half of its meat, and relied on imported feed to support its domestic meat production. The civilian population of the country was about 50 million.[36] It was one of the principal strategies of the Germans in the Battle of the Atlantic to attack shipping bound for Britain, restricting British industry and potentially starving the nation into submission.

To deal with sometimes extreme shortages, the Ministry of Food instituted a system of rationing. To buy most rationed items, each person had to register at chosen shops, and was provided with a ration book containing coupons that were only valid at that shop. The shopkeeper was provided with enough food for registered customers. Purchasers had to take ration books with them when shopping, so that the relevant coupon or coupons could be cancelled.[37]

Trade unions

[edit]Unions became well represented in the war cabinet after Winston Churchill came to power in May 1940. He appointed Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport and General Workers' Union, as the Minister of Labour and National Service Furthermore other Labour Party leaders shared power equally with Conservatives.[38] Trade unions gave strong cooperation to the war effort and at first strikes were minimized. Union membership grew by a third from 1938, to 8.2 million in 1943.[39]

According to historian Margaret Gowing, the mobilization of Britain's workforce to meet enormous wartime demands in munitions production came in three distinct phases. In the initial phase leading up to May 1940, efforts to mobilize manpower were largely ineffective and fell short of meeting the nation's escalating labour demands. The second phase (spring 1940 - mid-1943) witnessed a remarkably efficient organization and deployment of both men and women into essential roles across key industries and vital government services. This period marked the pinnacle of Britain's manpower mobilization capabilities..[40]

With victory in sight, from mid-1943 onward, Britain's capacity to sustain its war effort became increasingly constrained by the shortage of additional manpower reserves to draw upon. Strike activity now became a major concern. Although illegal, there were 1,800 strikes in 1943, costing 1.8 million working days. Coal strikes accounted for much of the inaction.[41] With millions of men in uniform, Britain had reached the limits of its available civilian workforce. Overall, the government grappled with the immense challenge of effectively marshaling its human resources to meet the unprecedented labour requirements imposed by a total war.[42][43]

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

[edit]Scotland

[edit]

The outbreak of the world war in 1939 temporarily arrested the ongoing decline in heavy industry, with the city's shipyards and heavy industries working. To slow arms production down, the Luftwaffe bombed the Clydeside. The worst was the Clydebank Blitz in March 1941 that left tens of thousands of people homeless. Destruction of housing caused by the war would leave a lasting legacy for decades later.[44]

Wales

[edit]Wales had been hard hit by deindustrialisation and high unemployment in the 1920s and 1930s. The war turned the economy around.[45] Because much of Wales was too distant for German bombers and it had a large pool of unemployed men immediately available for work, it suddenly became an attractive relocation destination for war industries and ordinance factories. The historic basic industries of coal and steel saw a very heavy new demand. The best coal seams had long been depleted. It was more and more expensive to get to the remaining coal, but coal was urgently needed, and shipping it in from North America would overburden the limited supply system.[46]

Belfast

[edit]Belfast is a representative British city that has been well-studied by historians.[47][48] It was a key industrial city producing ships, tanks, aircraft, engineering works, arms, uniforms, parachutes and a host of other industrial goods. The unemployment that had been so persistent in the 1930s disappeared, and labour shortages appeared. There was a major munitions strike in 1944.[49] As a key industrial city, Belfast became a target for German bombing missions, but it was thinly defended; there were only 24 anti-aircraft guns in the city for example. The Northern Ireland government under Richard Dawson Bates (Minister for Home Affairs) had prepared too late, assuming that Belfast was far enough away to be safe. When Germany conquered France in Spring 1940 it gained closer airfields. The city's fire brigade was inadequate; there were no public air raid shelters as the Northern Ireland government was reluctant to spend money on them; and there were no searchlights in the city, which made shooting down enemy bombers all the more difficult. After seeing the Blitz in London in the autumn of 1940, the government began to build air raid shelters. In early 1941, the Luftwaffe flew reconnaissance missions that identified the docks and industrial areas to be targeted. Especially hard hit were the working class areas in the north and east of the city, where over 1000 were killed and hundreds were seriously injured. Many people left the city in fear of future attacks. The bombing revealed the terrible slum conditions. In May 1941, the Luftwaffe hit the docks and the Harland and Wolff shipyard, closing it for six months. Apart from the numbers of dead, the Belfast Blitz saw half of the city's houses destroyed. About £20 million worth of damage was caused. The Northern Ireland government was criticised heavily for its lack of preparation, and Northern Ireland's Prime Minister J. M. Andrews resigned. The bombing raids continued until the Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. From January 1942, United States soldiers began to arrive in Northern Ireland, in preparation for the Invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

Derry

[edit]With the outbreak of the Second World War and the start of the Battle of the Atlantic, the Admiralty decided to develop a large new naval base in Northern Ireland to serve as a base for convoy escorts, providing repair and refuelling facilities. Derry was selected as a prime location due to Londonderry Port being the UK's most westerly port, providing the fastest access into the Atlantic. The naval base, named HMS Ferret, was a shore establishment. It was given a ship's name as a stone frigate. After the end of the war, large numbers of captured German U-boats were surrendered to British forces on the Scottish and Irish coasts and were brought to Lisahally.

Civilian casualties

[edit]Figures produced by the Ministry of Home Security give a total of 60,595 civilians killed and 86,182 seriously wounded, directly due to enemy action.

| Year | Dead | Seriously injured |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 23,767 | 30,529 |

| 1941 | 20,885 | 21,841 |

| 1942 | 3,236 | 4,150 |

| 1943 | 2,372 | 3,450 |

| 1944 | 8,475 | 21,989 |

| 1945 | 1,860 | 4,223 |

Of these, 51,509 were killed by bombing, 8,398 by V-1 flying bombs or V-2 rockets, and 148 by artillery bombardment. These figures do not include 1,200 killed while on duty with the Home Guard, or 32,000 civilian merchant seamen lost at sea.[51] The total civilian deaths represent 0.1 percent of the United Kingdom population,[50] or about 15 percent of Britain's war dead.[51]

Society and culture

[edit]Evacuations

[edit]

Public opinion in the 1930s was horrified at this prospect of massive bombing of major cities. The government planned to evacuate schoolchildren and others to towns and rural areas where they would be safe. Operation Pied Piper began on 1 September 1939, and relocated more than 3.5 million children and teachers - about half from London. The average evacuee travelled about 40 miles, but some travelled longer distances. There was no bombing in 1939, so they soon returned home. After a German invasion was possible and the Blitz began in September 1940, there was a second major wave of evacuation in June 1940 from targeted cities. There were also small-scale evacuations of children to Canada. Many families relocated to safer areas on their own. The host families worked well with most children, however there was a minority from poor, undernourished, unhygienic and uncooperative environments who brought along a strong distrust of authority. The confrontation was an eye-opener to both sides, and played a role in convincing the British middle-class to support expanded welfare programs. For the first time it became clear that middle class and rich people needed help too - they were bombed out of their homes and schools as well. Sociologist Richard Titmuss argues, "Reports in 1939 about the condition of evacuated mothers and children aroused the conscience of the nation in the opening phase of the war." He states that the national government:

- assumed and developed a measure of direct concern for the health and well-being of the population which, by contrast with the role of Government in the nineteen-thirties, was little short of remarkable. No longer did concern rest on the belief that, in respect to many social needs, it was proper to intervene only to assist the poor and those who were unable to pay for services of one kind and another. Instead, it was increasingly regarded as a proper function or even obligation of Government to ward off distress and strain not only among the poor but almost all classes of society.[52]

Fear

[edit]

Historian Amy Bell interprets private diaries, psychologists' notes, and fiction written by Londoners during the war "to reveal the hidden landscapes of fear in a city at war." They feared loss of property, loss of their homes and those of family and friends, destruction of their churches and shops, and their own injury and death. Many saw London as a "potential canker in the heart of Imperial Britain," with British civilisation highly vulnerable to internal weaknesses stemming from an "enemy within," specifically, the cowardice among those who remained in London during the war. Worried Londoners often identified as especially susceptible to this weakness the working classes, Jews, and children.[53]

Education

[edit]The quality of elementary education in major cities declined because of poor leadership in handling crises, confusion and inconsistency in evacuation and school closings, the destruction of some buildings in air raids, and the military requisition of others. Students were emotionally upset by the bombings; there were endemic shortages of supplies and teachers. The Education Act 1944 had a major impact on improving secondary schools after 1945, but did little for elementary schools. A lesser level of disruption took place in smaller places that were not bombing targets.[54][55][56]

Religion

[edit]All the churches gave enthusiastic support for the war, using their facilities to assist the displaced and comfort the fearful. At the local level, established religion remained a vibrant force. Prayer and Sunday services helped many people handle the horrors and the unknowns of warfare. City people reflected on the reality of sudden death as they huddled in air raid shelters.[57] Some sang:

God is our refuge, be not afraid,

He will be with you all through the raid.[58]

They told each other how miracles were protecting Britain, pointing to the Miracle of Dunkirk, and how this church and that cathedral miraculously survived the blitz.

Not all churches survived the blitz, over 15,000 church buildings were damaged; the Methodists had 9000 churches, of which 800 were totally destroyed. Many laymen who had volunteered for church work before the war, now turned their attention to civil defence.[59]

The Church of England saw its role as the moral conscience of the state. George Bell, Bishop of Chichester and a few clergymen spoke out that the aerial bombing of German cities was immoral. They were grudgingly tolerated. Bishop Bell was chastised by fellow clergy members and passed over for promotion. The Archbishop of York replied, "it is a lesser evil to bomb the war-loving Germans than to sacrifice the lives of our fellow countrymen..., or to delay the delivery of many now held in slavery".[60][61] Diplomat Harold Nicolson was on the BBC Board when it discussed whether clergy should broadcast forgiveness of our enemies. He told the Board, "I prefer that to the clergy who seek to pretend that the bombing of Cologne was a Christian act. I wish the clergy would keep their mouths shut about the war. It is none of their business."[62]

Standards of morality in Britain changed dramatically after the world wars, in the direction of more personal freedom, especially in sexual matters. The Church of England and the Catholic Church tried to hold the line and stop the rapid trend toward divorce, while the Dissenters were coming to terms with the new reality of divorced members.[63]

While the Church of England was historically identified with the upper-classes, and with the rural gentry, Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple (1881 – 1944) was both a prolific theologian and a social activist, preaching Christian socialism and taking an active role in the Labour Party until 1921.[64] He advocated a broad and inclusive membership in the Church of England as a means of continuing and expanding the church's position as the established church. He became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1942, and the same year he published Christianity and Social Order. The best-seller attempted to marry faith and socialism—by "socialism" he meant a deep concern for the poor. The book helped solidify Anglican support for the emerging welfare state. Temple was troubled by the high degree of animosity inside, and between the leading religious groups in Britain. He promoted ecumenicism, working to establish better relationships with the Nonconformists, Jews and Catholics, managing in the process to overcome his anti-Catholic bias.[65][66]

Gambling

[edit]The experience of total war in 1939–1945 meant much less leisure time and highly restricted transportation. So attendance fell at gambling venues such as racetracks for horses and dogs. However the amount of betting stayed high. Anti-gambling organizations saw the national emergency as an opportunity to shut down many legitimate gambling activities, but the early successes in curtailing horse racing, dog racing and football—which were the main topics of gambling—were soon reversed as the government saw gambling as a necessary psychological outlet in a time of highly restricted leisure opportunities. This renewed opportunities such as 'unity' football pools and a larger number of illegal local bookmakers. For the first time there was heavy gambling on Irish horse races, which were not interrupted during the war. The government provided the extra petrol needed for the movement of racehorses and dogs.[67]

Women

[edit]Mobilisation

[edit]

Historians credit Britain with a highly successful record of mobilising the home front for the war effort, in terms of mobilising the greatest proportion of potential workers, maximising output, assigning the right skills to the right task, and maintaining the morale and spirit of the people.[68] Much of this success was due to the systematic planned mobilisation of women, as workers, soldiers and housewives, enforced after December 1941 by conscription.[69] The women supported the war effort, and made the rationing of consumer goods a success. In some ways, the government over-responded, evacuating too many children in the first days of the war, closing cinemas as frivolous then reopening them when the need for cheap entertainment was clear, sacrificing cats and dogs to save a little space on shipping pet food, only to discover an urgent need to keep the rats and mice under control.[70] In the balance between compulsion and volunteering, the British relied successfully on volunteering. The success of the government in providing new services, such as hospitals and school lunches, as well as egalitarian spirit, contributed to widespread support for an enlarged welfare state. Munitions production rose dramatically, and the quality remained high. Food production was emphasised, in large part to free shipping for munitions.[71]

Parents had much less time to supervise their children, and there were fears of juvenile delinquency, especially as older teenagers took jobs and emulated their older siblings in the service. The government responded by requiring all young people over 16 to register, and expanded the number of clubs and organisations available to them.[72]

Relationships with American GIs

[edit]

There were approximately 46,000 American GIs in Britain during the early 50s, largely based in East Anglia and Burtonwood, Lancashire.[73] During this period there were growing anxieties about female sexuality, and 'public concern became especially pronounced after the arrival of American troops during the summer and autumn of 1942'.[74] There was increased attention to the behaviour of young girls that would loiter around the army bases like Burtonwood and spend time with the American troops. Illegitimacy rates went up during the war years and there was great social concern about preserving the British national identity. However, this became more of an issue when these young women were involved in relationships with black American soldiers. Women were given the central role and criticised for their sexual impropriety when the soldier was white; however, when the relationship involved an African-American soldier, the blame and criticism was shifted to the man.[75] Women were portrayed as vulnerable to these men and there were social concerns about how "half-caste" babies 'threatened to blur the racial lineaments of British national identity.'[1]

Venessa Baird, born in April 1958 to a Liverpudlian mother and Black GI based at Burtonwood airfield,[76] is one of many mixed-race babies that came of the interracial relationships between British women and African-American troops during World War II. Baird's father did not know about her birth, and her mother's father was extremely disapproving, so Baird's mother and grandmother left Liverpool and went to Norwich.[77] Baird explains how there was a small and accepting community in Burtonwood and the women that had met African-American men at Burtonwood were good friends and formed a 'large extended family' with their mixed-race children.[78]

See also

[edit]- Feeding Britain in World War II

- Timeline of the United Kingdom home front during World War II

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

- London in World War II

- Ministry of Information (United Kingdom)

- History of the United Kingdom during the First World War

- United States home front during World War II

- Diplomatic history of World War II

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hughes, J. R. T. (1958). "Financing the British War Effort". Journal of Economic History. 18 (2): 193–199. doi:10.1017/S0022050700077718. JSTOR 2115103. S2CID 154148525.

- ^ Mark Donnelly, Britain in the Second World War (1999) is a short survey

- ^ Angus Calder, The people's war: Britain, 1939–1945 (1969)

- ^ Brian Harrison, "The rise, fall and rise of political consensus in Britain since 1940." History 84.274 (1999): 301-324. online

- ^ Alfred F. Havighurst, Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century (1962) ch 9

- ^ Calder, The People's War: Britain, 1939–45 (1969) pp. 276–83, 411–30

- ^ Richard Titmuss, Essays on 'the welfare state (1958), pp. 75-87.

- ^ Paul Addison, The Road to 1945, pp 13-14, 239.

- ^ John Bew, Clement Attlee (2017), pp 267-68. 294-95.

- ^ Sidney Pollard, The development of the British economy 1914–1950 (1962 and later editions) pp 339–48

- ^ F. M. Leventhal, Twentieth-Century Britain: an Encyclopedia (1995) pp 74–75, 251-52, 830

- ^ Kevin Jefferys, "R. A. Butler, the Board of Education and the 1944 Education Act," History (1984) 69#227 pp 415–431.

- ^ Brian Abel‐Smith, "The Beveridge report: Its origins and outcomes." International Social Security Review (1992) 45#1‐2 pp 5–16. doi:10.1111/j.1468-246X.1992.tb00900.x

- ^ Harriet Jones, "'This is magnificent!': 300,000 houses a year and the Tory revival after 1945." Contemporary British History 14#1 (2000): 99-121.

- ^ Peter Malpass, "Wartime planning for post-war housing in Britain: the Whitehall debate, 1941-5." Planning Perspectives 18#2 (2003): 177-196.

- ^ Peter Malpass, "Fifty years of British housing policy: Leaving or leading the welfare state?." International Journal of Housing Policy 4#2 (2004): 209-227.

- ^ Broadberry, Stephen; Howlett, Peter (1998). "The United Kingdom: 'Victory at all costs'". In Harrison, Michael (ed.). The economics of World War II: Six great powers in international comparison (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 47, 72.

- ^ Broadberry, Stephen; Howlett, Peter (1998). "The United Kingdom: 'Victory at all costs'". In Harrison, Michael (ed.). The economics of World War II: Six great powers in international comparison (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 69.

- ^ Michael Geyer and Adam Tooz, eds.e (2015). The Cambridge History of the Second World War: Volume 3, Total War: Economy, Society and Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9781316298800.

- ^ Marcelo de Paiva Abreu, "India as a creditor: sterling balances, 1940-1953." (Department of Economics, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, 2015) online

- ^ Walter Yust, ed. Ten Eventful years (1947) 2:859

- ^ a b Hancock, W. K.; Gowing, M. M. (1949). British War Economy. p. 154, 168.

- ^ "BBC - WW2 People's War - Supporting the War Effort - Recycling and Saving".

- ^ David Edgerton, Warfare State: Britain, 1920–1970 (Cambridge UP, 2005).

- ^ Peter Howlett, "Resource allocation in wartime Britain: The case of steel, 1939-45," Journal of Contemporary History, (July 1994) 29#3 pp 523-44

- ^ Postan (1952), Chapter 4.

- ^ Hancock, British War Economy online p 353

- ^ Roger Chickering; et al. (2005). A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1937-1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780521834322.

- ^ Hancock (1949) p 550.

- ^ Calder, The People's War (1969) pp 411–30

- ^ Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant (2013). Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. University of Pittsburgh Pre. p. 106. ISBN 9780822944256.

- ^ Emma Vickers, "'The Forgotten Army of the Woods': The Women's Timber Corps during the Second World War" Agricultural History Review (2011) 59#1 101-112.

- ^ Gowdy-Wygant, Cultivating Victory pp 131-64.

- ^ Franklin Ginn, "Dig for victory! New histories of wartime gardening in Britain." Journal of Historical Geography 38#3 (2012): 294-305.

- ^ Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina (2002), Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls and Consumption, 1939–1955

- ^ Macrory, Ian (2010). Annual Abstract of Statistics (PDF) (2010 ed.). Office for National Statistics.

- ^ Calder, People's War pp 380-86.

- ^ Alan Bullock, The Life and Times of Ernest Bevin: volume two: Minister of Labour, 1940-1945 (1967), pp.1-17.

- ^ Calder, The People's War (1969) p. 394.

- ^ Margaret Gowing, "The organisation of manpower in Britain during the Second World War." Journal of Contemporary History 7.1 (1972): 147-167.

- ^ Keith Gildart, "Coal strikes on the home front: miners' militancy and socialist politics in the second world war." Twentieth Century British History 20.2 (2009): 121-151.

- ^ Gowing, "The organisation of manpower in Britain during the Second World War."

- ^ Denis Barnes, and Eileen Reid, "A new relationship: trade unions in the Second World War." in Trade Unions in British Politics ed. by Ben Pimlott and Chris Cook, (2nd ed. 1991) pp.137–155 (1982).

- ^ Ian Johnston, Ships for a Nation: John Brown & Company, Clydebank (2000).

- ^ D.W. Howell and C. <gwmw class="ginger-module-highlighter-mistake-type-1" id="gwmw-15612959063790447011684">Baber</gwmw>. "Wales." in F.M.L. Thompson, ed., The Cambridge social history of Britain 1750 – 1950 (1990), 1:310.

- ^ D. A. Thomas, "War and the Economy: The South Wales Experience" in C. <gwmw class="ginger-module-highlighter-mistake-type-1" id="gwmw-15612959066022485668733">Baber</gwmw> and L.J. Williams, eds., Modern South Wales: Essays in Economic History (U of Wales Press, 1986) pp 251-77.

- ^ Brian Barton, "The Belfast Blitz: April–May 1941," History Ireland, (1997) 5#3 pp 52–57

- ^ Robson S. Davison, "The Belfast Blitz," Irish Sword: Journal of the Military History Society of Ireland, (1985) 16#63 pp 65–83

- ^ Boyd Black, "A Triumph of Voluntarism? Industrial Relations and Strikes in Northern Ireland in World War Two," Labour History Review (2005) 70#1 pp 5–25

- ^ a b "THE BOMBING OF BRITAIN 1940-1945 EXHIBITION" (PDF). humanities.exeter.ac.uk. University of Exeter, Centre for the Study of War, State and Society. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b Brayley, Martin (2012-07-20). The British Home Front 1939–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1841766614. (Introduction)

- ^ Richard Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy (1950), pages 506 and 507. online free

- ^ Amy Bell, "Landscapes of Fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945." Journal of British Studies 48.1 (2009): 153-175.

- ^ Eric Hopkins, "Elementary education in Birmingham during the Second World War." History of education 18#3 (1989): 243-255.

- ^ Emma Lautman, "Educating Children on the British Home Front, 1939-1945: Oral History, Memory and Personal Narratives." History of education researcher 95 (2015): 13-26.

- ^ Roy Lowe, "Education in England during the Second World War." in Roy Lowe, ed., Education and the Second World War: studies in schooling and social change (1992) pp 4-16.

- ^ Stephen Parker, Faith on the Home Front: Aspects of Church Life and Popular Religion in Birmingham 1939-1945 (2005).

- ^ Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-1945 (1969) p 480.

- ^ Calder, The People's War (1969) p 479

- ^ Chris Brown (2014). International Society, Global Polity: An Introduction to International Political Theory. p. 47. ISBN 9781473911284.

- ^ Andrew Chandler, "The Church of England and the obliteration bombing of Germany in the Second World War." English Historical Review 108#429 (1993): 920-946.

- ^ Calder, The People's War (1969) p 477

- ^ G. I. T. Machin, "Marriage and the Churches in the 1930s: Royal abdication and divorce reform, 1936–7." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 42#1 (1991): 68-81.

- ^ Adrian Hastings, "Temple, William (1881–1944)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/36454

- ^ Dianne Kirby, "Christian co-operation and the ecumenical ideal in the 1930s and 1940s." European Review of History 8#1 (2001): 37-60.

- ^ F. A. Iremonger, William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury: His Life and Letters (1948) pp 387-425. online Archived 2020-09-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mike Huggins, "Sports gambling during the Second World War: a British entertainment for critical times or a national evil?." International Journal of the History of Sport 32.5 (2015): 667-683.

- ^ Robin Havers, The Second World War: Europe, 1939–1943 (2002) Volume 4, p 75

- ^ Hancock, W.K. and Gowing, M.M. British War Economy (1949)

- ^ Arthur Marwick, Britain in the Century of Total War: Peace and Social Change, 1900–67 (1968), p. 258

- ^ Calder, The People's War: Britain, 1939–45 (1969) pp 276–83.

- ^ Marwick, Britain in the Century of Total War: Peace and Social Change, 1900–67 (1968), pp. 292–94, 258

- ^ "Black GIs in Britain". The Mixed Museum. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ Rose, Sonya O. (1997). "Girls and GIs: Race, Sex, and Diplomacy in Second World War Britain". The International History Review. 19 (1): 146–160. doi:10.1080/07075332.1997.9640780. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40108089.

- ^ Rose, Sonya O. (1997). "Girls and GIs: Race, Sex, and Diplomacy in Second World War Britain". The International History Review. 19 (1): 146–160. doi:10.1080/07075332.1997.9640780. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40108089.

- ^ "Black GIs in Britain". The Mixed Museum. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "Black GIs in Britain". The Mixed Museum. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "Black GIs in Britain". The Mixed Museum. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Addison, Paul. "The Impact of the Second World War," in Paul Addison and Harriet Jones, eds. A Companion to Contemporary Britain: 1939-2000 (2005) pp 3–22.

- Allport, Alan. Britain at Bay: The Epic Story of the Second World War, 1938–1941 (2020)

- Calder, Angus . The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969), highly influential survey; online review

- Field, Geoffrey G. (2011) Blood, Sweat, and Toil: Remaking the British Working Class, 1939-1945 DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199604111.001.0001 online

- Gardiner, Juliet. (2004) Wartime: Britain 1939–1945 782pp; comprehensive social history

- Levine, Joshua. The Secret History of the Blitz (2015).

- Marwick, Arthur. The Home Front: The British and the Second World War. (1976).

- Overy, Richard. Britain at War: From the Invasion of Poland to the Surrender of Japan: 1939–1945 (2011).

- Overy, Richard, ed. What Britain Has Done: September 1939 - 1945 a Selection of Outstanding Facts and Figures (2007)

- Taylor, A. J. P. English History 1914-1945 (1965) pp 439–601.

- Todman, David. Britain's War: 1937-1941 (vol 1, Oxford UP, 2016); 828pp; comprehensive coverage of home front, military, and diplomatic developments; Excerpt

Politics

[edit]- Addison, Paul. The road to 1945: British politics and the Second World War (1975; 2nd ed. 2011), a standard scholarly history of wartime politics.

- Addison, Paul. Churchill on the Home Front, 1900-1955 (1992) ch 10-11.

- Bew, John. Clement Attlee: The Man Who Made Modern Britain (2017).

- Brooke, Stephen. Labour's war: the Labour party during the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 1992)

- Crowcroft, Robert. "'Making a Reality of Collective Responsibility': The Lord President's Committee, Coalition and the British State at War, 1941–42." Contemporary British History 29.4 (2015): 539-562. online

- Fielding, S., P.Thompson and N. Tiratsoo, 'England Arise!': The Labour Party and Popular Politics in 1940s Britain (Manchester UP, 1995),

- Fielding, Steven. "What did 'the people' want?: the meaning of the 1945 general election." Historical Journal (1992) 35#3 pp: 623–639. 2639633 online

- Fry, Geoffrey K. "A Reconsideration of the British General Election of 1935 and the Electoral Revolution of 1945," History (1991) 76#246 pp 43–55.

- Gilbert, Bentley B. "Third Parties and Voters' Decisions: The Liberals and the General Election of 1945." Journal of British Studies (1972) 11(2) pp: 131–141. online

- Harrison, Brian. "The rise, fall and rise of political consensus in Britain since 1940." History 84.274 (1999): 301-324. online

- Jefferys, Kevin. "British politics and social policy during the Second World War." Historical Journal 30#1 (1987): 123-144. online

- Kandiah, Michael David. "The conservative party and the 1945 general election." (1995): 22–47.

- McCallum, R.B. and Alison Readman. The British general election of 1945 (1947) the standard political science study

- McCulloch, Gary. "Labour, the Left, and the British General Election of 1945." Journal of British Studies (1985) 24#4 pp: 465–489. online

- Pelling, Henry. "The 1945 general election reconsidered." Historical Journal (1980) 23(2) pp: 399-414. JSTOR: 2638675

- Smart, Nick. British strategy and politics during the phony war: before the balloon went up (Greenwood, 2003).

Economy, labour and war production

[edit]- Aldcroft, Derek H. British Economy: Years of Turmoil, 1920-51 v. 1 (1986) pp 164–200. online

- Barnes, Denis, and Eileen Reid. "A new relationship: trade unions in the Second World War." in Trade Unions in British Politics ed. by Ben Pimlott and Chris Cook, (2nd ed. 1991) pp.137–155 (1982)

- Barnett, Corelli. The Audit of War: The Illusion and Reality of Britain as a Great Nation. (Macmillan, 1986). online

- Bullock, Alan. The Life and Times of Ernest Bevin: volume two: Minister of Labour, 1940-1945 (1967) online

- Burridge, T.D. British Labour and Hitler's War (1976) online

- Edgerton, David. Britain's war machine: weapons, resources, and experts in the Second World War (Oxford UP, 2011).

- Edgerton, David. Warfare State: Britain, 1920–1970 (Cambridge UP, 2005)

- Gowing, Margaret. "The organisation of manpower in Britain during the Second World War." Journal of Contemporary History 7.1 (1972): 147-167

- Hammond, R. J. Food and agriculture in Britain, 1939–45: Aspects of wartime control (Stanford U.P. 1954); summary of his three volume official history entitled Food (1951–53)

- Hancock, W. Keith and Margaret M. Gowing. British War Economy (1949) British War Economy.

- Harrison, Mark, ed. The Economics of World War II (Cambridge UP, 1998).

- Hughes, J. R. T. "Financing the British War Effort," Journal of Economic History (1958) 18#2 pp. 193–199 in JSTOR

- Pollard, Sidney. The development of the British economy, 1914-1967 (2nd ed. 1969) pp 297–355; broad coverage of all major economic topics.

- Postan, Michael British War Production (1952) (official History of the Second World War). online.

- Roodhouse, Mark. Black Market Britain, 1939–1955 (Oxford UP, 2013)

- Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls & Consumption, 1939–1955 (2000) online

Localities and regions

[edit]- Beardon, James. The Spellmount Guide to London in the Second World War (2014)

- Broomfield, Stuart. Wales at War: The Experience of the Second World War in Wales (2011).

- Finlay, Richard J. Modern Scotland 1914-2000 (2006), pp 162–197.

- MacDonald, Catriona MM. "'Wersh the Wine O'Victorie': Writing Scotland's Second World War." Journal of Scottish Historical Studies 24#2 (2004): 105-112; finds many specialized studied but no overall history.

- Ollerenshaw, Philip. "War, industrial mobilisation and society in Northern Ireland, 1939–1945." Contemporary European History 16#2 (2007): 169-197.

- Short, Brian. The Battle of the Fields: Rural Community and Authority in Britain during the Second World War (2014).

- Thoms, David. War, Industry & Society: The Midlands, 1939-45 (HIA Book Collection). (1989). 197p.

- Woodward, Guy. Culture, Northern Ireland, and the Second World War (Oxford UP, 2015)

Society and culture

[edit]- Brivati, Brian, and Harriet Jones, ed. What Difference Did the War Make? The Impact of the Second World War on British Institutions and Culture. (Leicester UP; 1993).

- Crang, Jeremy A. The British Army and the People's War, 1939-1945 (Manchester UP, 2000) on the training of 3 million draftees

- Hayes, Nick, and Jeff Hill. 'Millions like us'?: British culture in the Second World War (1999)

- Hinton, James. The Mass Observers: A History, 1937-1949 (2013).

- Howell, Geraldine. Wartime fashion: from Haute Couture to homemade, 1939-1945 (A&C Black, 2013).

- Hubble, Nick. Mass-Observation and Everyday Life (Palgrave Macmillan. 2006).

- Jones, Helen (2006). British civilians in the front line: air raids, productivity and wartime culture, 1939-45. Manchester UP. ISBN 9780719072901.

- Lawson, Tom. God and War: The Church of England and armed conflict in the twentieth century (Routledge, 2016).

- MacKay, Marina. Modernism and World War II (Cambridge UP, 2007).

- McKibbin, Ross. Classes and Cultures: England 1918-1951 (2000) very wide-ranging social history.

- Parker, Stephen. Faith on the Home Front: Aspects of Church Life and Popular Religion in Birmingham, 1939-1945 (Peter Lang, 2006).

- Rose, Sonya O. Which People's War?: National Identity and Citizenship in Wartime Britain 1939-1945 (2003)

- Savage, Mike. "Changing social class identities in post-war Britain: Perspectives from mass-observation." Sociological Research Online 12#3 (2007): 1-13. online

- Smith, Harold L., ed. War and social change: British society in the Second World War (Manchester UP, 1986) online.

- Taylor, Matthew. "Sport and Civilian Morale in Second World War Britain." Journal of Contemporary History (2016): online

Propaganda, morale and media

[edit]- Balfour, Michael. Propaganda in War, 1939–1945: Organisations, Policies and Publics in Britain and Germany (2011).

- Beaven, Brad, and John Griffiths. "The blitz, civilian morale and the city: mass-observation and working-class culture in Britain, 1940–41." Urban History 26#1 (1999): 71-88.

- Fox, Jo. Film propaganda in Britain and Nazi Germany: World War II cinema (2007).

- Fox, Jo. "Careless Talk: Tensions within British Domestic Propaganda during the Second World War." Journal of British Studies 51#4 (2012): 936-966.

- Holman, Valerie. Print for Victory: Book Publishing in England 1939-45 (2008).

- Jones, Edgar, et al. "Civilian morale during the Second World War: Responses to air raids re-examined." Social History of Medicine 17.3 (2004): 463-479. online

- Littlewood, David. "Conscription in Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada during the Second World War," History Compass 18#4 (2020) online

- Lovell, Kristopher. "The 'Common Wealth Circus': Popular Politics and the Popular Press in Wartime Britain, 1941–1945." Media History 23#3-4 (2017): 427-450.

- Maartens, Brendan. "To Encourage, Inspire and Guide: National service, the people's war and the promotion of civil defence in interwar Britain, 1938–1939." Media History 21#3 (2015): 328-341.

- Mackay, Robert. Half the battle: civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War (Manchester UP), 2010.

- Mackenzie, S. Paul. British War Films, 1939-45 (A&C Black, 2001).

- McLaine, Ian. Ministry of Morale: Home Front Morale and the Ministry of Information in World War II (1979),

- Maguire, Lori. "'We Shall Fight': A Rhetorical Analysis of Churchill's Famous Speech." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 17#2 (2014): 255-286.

- Nicholas, Siân. The Echo of War: Home Front Propaganda and the Wartime BBC, 1939-1945 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1996).

- Toye, Richard. The Roar of the Lion: the untold story of Churchill's World War II speeches (Oxford UP, 2013).

Welfare state

[edit]- Lowe, Rodney. "The Second World War, consensus, and the foundation of the welfare state." Twentieth Century British History 1#2 (1990): 152-182.

- Page, Robert M. Revisiting the welfare state (McGraw-Hill Education (UK), 2007).

- Titmuss, Richard M. (1950) Problems of Social Policy. (Official History of the Second World War). London: HMSO. online free

Women and family

[edit]- Braybon, Gail, and Penny Summerfield. (1987) Out of the cage: women's experiences in two world wars

- Costello, John. Love, Sex, and War: Changing Values, 1939-1945 (1985)

- Gartner, Niko. Operation Pied Piper: the wartime evacuation of schoolchildren from London and Berlin 1938–46 (2012)

- Harris, Carol. Women at War 1939-1945: The Home Front. (2000) Thrupp: Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-7509-2536-1.

- Hinton, James. Women, social leadership, and the Second World War: Continuities of class (Oxford UP, 2002.

- Lant, Antonia Caroline. Blackout: Reinventing women for wartime British cinema (Princeton UP, 2014)

- Moshenska, Gabriel. "Spaces for Children: School Gas Chambers and Air Raid Shelters in Second World War Britain." in Reanimating Industrial Spaces: Conducting Memory Work in Post-industrial Societies 66 (2014): 125+.

- Noakes, Lucy. Women in the British Army: War and the Gentle Sex, 1907–1948 (Routledge, 2006).

- Summerfield, Penny. (1999) "What Women Learned from the Second World War," History of Education 18: 213–229;

Official histories

[edit]- Hammond, R.J. Food: Volume 1, Studies of Administration and Control online

- Hancock, W. K. and Gowing, M.M. British War Economy (1949) (official History of the Second World War). London: HMSO and Longmans, Green & Co. Available on line at: British War Economy.

- Hancock, W. K. Statistical Digest of the War (1951) (official History of the Second World War). London: HMSO and Longmans, Green & Co. Available on line at: Statistical Digest of the War.

Historiography and memory

[edit]- Chapman, James. "Re-presenting war: British television drama-documentary and the Second World War." European Journal of Cultural Studies 10.1 (2007): 13-33.

- Eley, Geoff. "Finding the People's War: Film, British Collective Memory, and World War II." The American Historical Review 106#3 (2001): 818-838. online

- Harris, Jose. "War and social history: Britain and the home front during the Second World War," Contemporary European History (1992) 1#1 pp 17–35.

- Smith, Malcolm. Britain and 1940: history, myth and popular memory (2014).

- Summerfield, Penny. (1998) "Research on Women in Britain in the Second World War: An Historiographical Essay," Cahiers d'Histoire du Temps Présent 4: 207–226.

- Twells, Alison. "'Went into raptures': reading emotion in the ordinary wartime diary, 1941–1946." Women's History Review 25.1 (2016): 143-160; shows how ordinary diaries can be used to move beyond cultural directives concerning appropriate female emotional expression to develop a greater understanding of the daily crafting of the modern self.

Primary sources

[edit]Central Statistical Office. Statistical digest of the war (1951) official homefront data, social and economic, as well as war production, 1939-1945. online; can be downloaded

- Addison, Jeremy A., Paul Addison, and Paul Crang, eds. Listening to Britain: Home Intelligence Reports on Britain's Finest Hour-May to September 1940 (2011).

- Boston, Anne and Jenny Hartley, eds. Wave Me Goodbye and Hearts Undefeated Omnibus (2003) 630pp; fiction and non-fiction written by women during the war.

- Calder, Angus, and Dorothy Sheridan, eds. Speak for yourself: a mass-observation anthology, 1937-1949 (1984), 229pp

- Garfield, Simon, ed. Private battles: our intimate diaries - how the war almost defeated us (2007) online free, from the Mas Observation collection

- Sheridan, Dorothy, ed. Wartime women: a mass-observation anthology, 1937-45 (2000) online free