The Maiden in the Tower

| The Maiden in the Tower | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Jean Sibelius | |

The composer (c. 1895) | |

| Native name | Jungfrun i tornet |

| Catalogue | JS 101 |

| Text | Libretto by Rafael Hertzberg |

| Language | Swedish |

| Composed | 1896 (withdrawn 1896) |

| Publisher | Hansen (1983)[1] |

| Duration | 35.5 mins.[2] |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 7 November 1896[3] |

| Location | Helsinki, Grand Duchy of Finland |

| Conductor | Jean Sibelius |

| Performers | Helsinki Philharmonic Society |

The Maiden in the Tower (in Swedish: Jungfrun i tornet; in Finnish: Neito tornissa; occasionally translated to English as The Maid in the Tower),[4] JS 101, is an opera ("dramatized Finnish ballad")[a] in one act—comprising an overture and eight scenes—written in 1896 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. The piece was a collaboration with the Finnish author Rafael Hertzberg, the Swedish-language libretto of whom tells a "simple tale of chivalry" that may nonetheless have had allegorical ambitions: the Bailiff (Imperial Russia) abducts and imprisons the Maiden (the Grand Duchy of Finland); although she endures hardship, she remains true to herself and is freed subsequently (Finland's independence) by her Lover (Finnish nationalists) and the Chatelaine of the castle (social reformers).

The opera premiered on 7 November 1896 at a lottery soirée to benefit the Helsinki Philharmonic Society, which Sibelius conducted, and its music school; the Finnish baritone Abraham Ojanperä and the Finnish soprano Ida Flodin sang the roles of the Bailiff and the Maiden, respectively. Although the critics praised Sibelius's music, they thought it was wasted on Hertzberg's lifeless libretto. After three performances, Sibelius withdrew the opera, saying he wanted to revise it. He never did, and with one exception (in 1900, he conducted a 12-minute concert overture that incorporated material from five of the opera's numbers),[b] he suppressed the work. (In 1914, for example, he quashed the Finnish soprano Aino Ackté's plans for a revival in Mikkeli.) The Maiden in the Tower would not receive its next complete performance until 28 January 1981, when Sibelius's son-in-law Jussi Jalas and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra resurrected it for a radio concert.

In the intervening decades, The Maiden in the Tower has entered neither the Finnish nor the international repertories, and its significance is therefore primarily as a historical curiosity: Sibelius's lone opera.[5] Accordingly, it has been recorded only a few times, with Neeme Järvi and the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra having made the world premiere studio recording in 1983. A typical performance lasts about 36 minutes.

History

[edit]Composition

[edit]On 25 April 1896 Sibelius promised the Finnish mezzo-soprano Emmy Achté that he would write a one-act stage work[6] for a lottery soirée to benefit Robert Kajanus's Helsinki Philharmonic Society and music school.[7] It was a curious moment in his career for Sibelius to agree to an opera-like project: since August 1894, he had labored to convert his abandoned, Finnish-language grand opera The Building of the Boat (Veneen luominen) into the tone poems The Wood Nymph (Skogsrået, Op. 15) and the four-movement The Lemminkäinen Suite (Op. 22); their respective premieres on 17 April 1895 and 13 April 1896 were the culmination of his metamorphosis from Wagner acolyte to "tone painter" in the tradition of Liszt.[8][9] But Sibelius probably thought the lottery soirée was a good cause, and moreover, a critical tool of the Finnish resistance. The musicologist and Sibelius biographer Glenda Dawn Goss describes these evenings as follows:

The faintly distasteful act of giving money to gamble for prizes was masked by the elaborate spectacle ... which proved to be an ideal device for raising money in support of national causes and ... promoting social cohesion and Finnish identity in a guise that the imperial censors would approve ... These entertainments ... with music, drama, dancing, drinking, and eating mingled with the fund-raising ... [comprised] lavish tableaux vivants in which key events from Finland's myths, landscapes, and history were colorfully dramatized ... Choruses, orchestras, and other musicians were brought to sing, play dance music, and perform new works, which the country's composers were prevailed upon to compose ... The very spectacle was enough to take one's breath away.[10]

Achté had earlier contracted the Finnish author Rafael Hertzberg to serve as librettist.[6] Although little is known about Hertzberg's writing process,[11] he produced a Swedish-language libretto based on a popular,[12] traditional Karelian,[13] Finnish-language folk ballad, Neitsyt kammiossa (In a Maiden's Bower),[14] which he described as "the oldest known Finnish drama—or rather an opera, because everything is sung".[15][c] Sibelius began composing in August, and met Hertzberg on 24 September—a month that found Sibelius overworked, as he had taken on teaching responsibilities at the Imperial Alexander's University of Finland following the retirement of Richard Faltin.[17] According to Achté, by the time rehearsals began a fortnight before the premiere, Sibelius had not yet finished the finale: "I constantly have to ... give him a very necessary reminder that we can't guess what his music is; we need the notes on the page".[18]

Premiere

[edit]Sibelius met his deadline, and The Maiden in the Tower premiered on 7 November 1896[d] at a sold-out concert [20] in the ballroom of the Helsinki Society Hall.[21] Ironically given Sibelius's repudiation of Wagner, the soirée began with the Helsinki Philharmonic Society—in the stands and directed by Kajanus—playing the march from the overture to Tannhäuser.[20] Afterwards, Sibelius assumed conducting duties, with the twenty-person orchestra[16] now positioned in the pit and, for dramatic effect, the amateur chorus behind the stage.[22] The four soloists, who sang before a "striking" backdrop of a towered castle to the right of a springtime birch forest,[20] were: the soprano Ida Flodin as the Maiden, the baritone Abraham Ojanperä as the Bailiff, the tenor E. Eklund as the Lover,[e] and Achté as the Chatelaine. At the end of the opera, the audience cheered Sibelius and the soloists to several curtain calls;[20] the evening continued with the lottery as well as additional tableaux.[f] The Maiden in the Tower was repeated on 9 and 16 November—the former for the benefit of the orchestra and music school, while the latter raised funds for Sibelius.[24]

The critics penned mixed reviews, skewering Hertzberg's libretto but mostly complimenting Sibelius's music. Hufvudstadsbladet printed an unsigned review that found the opera had a "genuinely Sibelian mood" and "virtuoso instrumentation", especially for the woodwinds.[23] In Nya Pressen, 'Felicien' wrote that the "beautiful" music was "interesting ... and finely orchestrated", if "wasted" on such an underwhelming story.[20] In the same paper, Karl Flodin faulted Hertzberg's "uncomplicated" libretto as "too naive to captivate", but praised Sibelius's "glowing ... peculiar" music for having transformed the opera into an "outstanding work of domestic musical art". In particular, Flodin described Scene 1 as "poignant", with vocal writing for the Bailiff that "breathes insistent, hot longing" and for the Maiden that shows "disgust and trembling fear". He also enjoyed Scene 3's "utterly captivating" and "master[fully] paint[ed]" spring music, as well the "tender, erotic mood" of Scene 5's duet for the Maiden and the Lover; nevertheless, the Overture was "rather long" and the Maiden's prayer was "probably too drawn out", given that the balcony limited Ida Flodin's acting.[24]

In Päivälehti, Oskar Merikanto echoed Flodin: Hertzberg's libretto was "monotonous" and lacking in action, and Sibelius's music—though "masterful[ly]" orchestrated—exacerbated this "dull[ness]" with "interludes that were too long ... [leaving] the stage completely empty". Nevertheless, he found the arias for the Maiden and for the Lover "very successful and beautiful", although each could have benefited from concision. "It is natural that the first attempt is not always the best, and so it is here," Merikanto concluded. "[But] may [Sibelius] soon follow this work with a new, bigger opera in Finnish soon!"[25][g] Uusi Suometar ran an anonymous column that also noted The Maiden in the Tower's "Finnish stamp", before proclaiming its "pan-Europeanness", which the reviewer thought would be to the work's "great advantage ... because it has the opportunity to become a sensation even beyond our borders". However, like Merikanto, Uusi Suometar hoped that Sibelius would write a Finnish opera next.[26] Finally, in terms of the four soloists, all critics wrote glowingly of their singing (if not always their acting), although there was a sense that the production was under-rehearsed.[26][25]

Withdrawal and suppression

[edit]Sibelius withdrew The Maiden in the Tower after three performances, claiming that he wanted to revise the score.[27][28] As a result, several near-term productions of the opera had to be abandoned, the first of which was a probable performance at the Royal Swedish Opera at the end of 1896 or beginning of 1897.[6] Second, at the behest of Achté, Sibelius and the vocalists had agreed to mount The Maiden in the Tower for the Mikkeli (S:t Michel)[h] Song Festival in the summer of 1897.[27] This too was cancelled, as Sibelius had not yet finished his revisions—indeed, there is no evidence he ever began reworking the piece.[29] Additionally, Hertzberg was unavailable to overhaul his libretto, having died on 5 December 1896.[30] In a sketchbook, Sibelius jotted a sad waltz in F minor below the inscription: "Now Rafael is dead".[31]

Sibelius's thoughts returned to The Maiden in the Tower on several occasions. In 1900, he arranged a 12-minute concert overture that incorporated material from five of the opera's nine numbers and conducted it twice in Turku (Åbo)[h] in early April. A few years later, in June 1905 and October 1906, the Finnish writer Jalmari Finne—who was then director of the Viipuri (Vyborg)[h] rural theatre—wrote to Sibelius with a two-part plan to program The Maiden in the Tower: first for 1907, Scene 3 as a stand-alone piece at the Viipuri Song Festival; and second for February 1908, the entire opera. Finne would translate the libretto into Finnish. Sibelius agreed to the proposal, but for unknown reasons Finne's efforts never came to fruition.[32]

Sibelius had not given up on The Maiden in the Tower, however. First, his diary from the beginning of 1910, lists the opera—and parenthetically singles out the chorus's spring music from Scene 3—under the title "Old Pieces to be Revised".[33] Second, Sibelius's opus list from August 1911 places the overture to The Maiden in the Tower next to Kullervo (Op. 7, 1892) and connects the two with the inscription "reworkable". Sibelius may have considered uniting them into one piece, with the opera's concert overture from 1900 joining Kullervo's Movements II–V.[34] Yet, Sibelius never overhauled any part of the opera—as he put it later in life, "The maiden may remain in her tower".[28] When Emmy's daughter, the soprano Aino Ackté, wrote to him in November 1913 requesting to program The Maiden in the Tower in Finnish for the 1914 Mikkeli Song Festival,[i] Sibelius refused to budge: "With all my soul, I would like to be at your service ... But—it is absolutely impossible! ...The text!! As for the music, it should be reworked. But, I'm sorry, there is no time for that".[35]

Posthumous revival

[edit]Twenty-three years after Sibelius's death, The Maiden in the Tower received its twentieth-century premiere on 28 January 1981, when the composer's son-in-law Jussi Jalas conducted the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra at Finlandia Hall;[36] the four soloists were: MariAnn Häggander as the Maiden, Jorma Hynninen as the Bailiff, Peter Lindroos as the Lover, and Pia-Gunn Anckar as the Chatelaine.[36] The opera, performed as a concert item rather than staged, was broadcast live over Finnish radio.[36] According to Jalas, a proper historical contextualization of The Maiden in the Tower was important to Sibelius: he instructed that it should only be performed if accompanied by a presentation recounting its background, a wish that the musicologist and Sibelius biographer Erik Tawaststjerna's lecture—printed in the program and given by him over the radio—fulfilled.[37][36] Moreover, to resurrect the opera, Jalas commissioned new fair copies of the score, using Sibelius's autograph manuscript and the original orchestral parts by copyist Ernst Röllig.[13] In 1983, Edition Wilhelm Hansen published Jalas's sheet music; an updated edition arrived in 2014.[13]

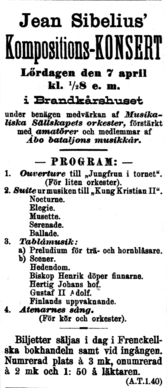

In 2019, the musicologist and conductor Tuomas Hannikainen deciphered the markings Sibelius had written in blue pencil over the opera's original sheet music.[38] Collectively, they constituted a hidden concert overture lasting about 12 minutes.[39][b] Sibelius arranged the piece in 1900 for concerts in Turku. He conducted the Turku Musical Society for its premiere at the Fire Brigade Hall on 7 April;[40] also on the program was the five-movement King Christian II Suite (Op. 27), excerpts from the Music for the Press Celebrations Days (JS 137), and The Song of the Athenians (Op. 31/3).[41][j] The next day, Sibelius repeated this program at the Old Academy Building.[41] Finally, on 10 April at the Fire Brigade Hall, José Eibenschütz conducted a third performance of the Concert Overture.[13] The critical reviews were brief but positive. Uusi Aura and Åbo Underrättelser observed that the Concert Overture was received with, respectively, "great pleasure"[40] and "sympathetic applause".[41] Åbo Tidning wrote that the Overture numbered among "Sibelius’s minor works" despite its "originality and richness of ... invention".[13]

Before Hannikainen's research, scholars had assumed that Sibelius had conducted in Turku the opera's original overture, despite the fact that it would have made an ineffective concert piece due to its short duration and inconclusive ending.[38] In 2019, Fennica Gehrman published as the Concert Overture, reconstructed and edited by Hannikainen. The piece received its world premiere on 23 May 2021, with Hannikainen conducting the chamber orchestra Avanti! at the Finnish House of Nobility.[39] Structurally, the piece incorporates elements from five of the opera's nine numbers, ordered as follows: the Overture (bars 1–238 in the Concert Overture), Scene 4 (bars 239–349), Scene 6 (bars 350–443), Scene 7 (bars 444–500), and Scene 8 (bars 501–639). Of these five numbers, all but Scene 4 are taken from the opera almost in their entirety.[47] While the scoring of the Concert Overture is identical to the opera, the vocal lines are absent—except in their essential moments, when they are replaced with instruments.[38]

Structure and roles

[edit]The Maiden in the Tower is in one act, comprising an overture and eight scenes. It features four vocal soloists, two arias, and three duets. A typical performance lasts about 36 minutes.

| Roles[48] | Appearances[48] | Voice type[48] | Premiere cast (7 November 1896)[20] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in English | in Swedish | |||

| The Maiden | Jungfrun | Scenes 1–3, 5, 8 | soprano | Ida Flodin |

| The Chatelaine | Slottsfrun | Scenes 7–8 | contralto[k] | Emmy Achté |

| The Lover | Älskaren | Scenes 4–8 | tenor | E. Eklund[e] |

| The Bailiff | Fogden | Scenes 1, 6–8 | baritone | Abraham Ojanperä |

| Chorus [peasants, servants] | Kören | Scenes 3, 7–8 | mixed choir | local amateurs |

- Overture: Allegro molto†

- Scene 1: Allegro molto. A duet for the Maiden and the Bailiff that ends with the first orchestral interlude.[49]

- Scene 2: Molto sostenuto. The Maiden's aria "Sancta Maria, mild och nåderik" ("Holy Mary, gracious and mild").[50][l]

- Scene 3: Allegro. Ends with the second orchestral interlude.[12]

- Scene 4: Allegro moderato† The Lover's aria "Ack, när jag ser hennes drag" ("Ah, when I see her face").[51]

- Scene 5: Largamente. A duet for the Maiden and the Lover.[52]

- Scene 6: Allegro molto† A duet for the Lover and the Bailiff.[27]

- Scene 7: Meno mosso†

- Scene 8: [Meno mosso]†

† Included, all or in part, in the concert overture Sibelius arranged in 1900.[53]

Synopsis

[edit]The Maiden in the Tower is a rescue opera[12] that tells a "simple tale of chivalry".[54] In Scene 1, the curtain rises to find the beautiful Maiden picking flowers along the seashore; in the background is a castle with a tower.[20] The Bailiff, emerging from the birch forest, comes upon her and professes his love: "sweetest virgin, thou my shining star". When his pleas do not persuade the Maiden, he seeks to seduce her with material riches. This proposal she also rebuffs, and so the Bailiff determines to take her as his bride by force; powerless, the maiden collapses into the arms of the "cowardly villain".[55] After a first orchestral interlude, Scene 2 finds the Maiden imprisoned in the castle. She kneels in prayer from the tower balcony,[20] and asks the Virgin Mary to protect her ("Sancta Maria, mild och nåderik").[56] In Scene 3, the Maiden overhears peasants singing about the change of season: "Now in forest the winds of spring are sighing ... winter's darkened skies flee the gaze of the sun". To her relief, she discerns her father's voice and believes her rescue is imminent. But the peasants disown her, believing that she has propositioned herself "for gold and gloss".[57]

After a second orchestral interlude, Scene 4 finds the Maiden's true love, a freeborn peasant[20] singing an aria in which he dreamily proclaims his desires ("Ack, när jag ser hennes drag"), although he wonders why she has been delayed from their rendezvous.[58] In Scene 5, the Lover overhears the Maiden lamenting her misfortune; he is shocked to find her in the Bailiff's possession: "How can I explain it that she is with the bailiff, she so pure and spotless"? From the balcony, she assures him of her faithfulness, exclaiming: "I love thee; by force the bailiff holds me captive, innocent I am!"; he promises to free her.[59] In Scene 6, the Lover accuses the Bailiff of wrongdoing, to which the imperious lawman responds with threats of reprisal: "And if thou wouldst defy me yet, let castle-dungeon thy repentance bring".[60] A duel is averted when, in Scene 7, the Chatelaine of the castle enters and demands the belligerents sheath their swords.[m] She heeds not the Bailiff's complaint, and grants the Maiden her freedom: "Here force was used against defenseless woman, whose innocence and virtue I know well. Set her free!"[62] In Scene 8, the Chatelaine's servants apprehend the Bailiff, and the Maiden and the Lover embrace. Amid the rejoicing, the Chatelaine affirms her dedication to justice: "Ever yet my wish has been defense of innocence, defense of right".[63]

Music

[edit]The Maiden in the Tower is scored for soprano, contralto,[k] tenor, baritone, mixed choir, flute (doubling piccolo), oboe, 2 clarinets (in B♭ and A), bassoon, 2 horns (in F), trumpet (in F), trombone, strings, bass drum, tambourine, triangle, and cymbals.[64] Relative to his other orchestral works, the forces Sibelius requires for The Maiden in the Tower are modest: only the clarinet and the horn is doubled, and he makes do with neither expansive percussion nor a large string section. The scoring thus gives the piece the feel of chamber music,[65] and in its sonority, it is reminiscent of Karelia (JS 115) from 1893; for example, the overture recalls the Intermezzo from the Karelia Suite (Op. 11).[66] Coloristically, the opera's idiom is relatively cheerful for Sibelius,[13] who is known for his darker textures and melancholy sound—although, Karl Flodin still discerned the composer's "distinctive basso continuo".[24]

Stylistically, commentators have detected echoes of Gounod's "erotic lyricism",[20] as well as Puccini's Italian verismo and "vocally grateful" bel canto in Scenes 2 and 4.[69] As for Wagner, Sibelius purposefully eschewed the techniques of the German master,[70] his use of Wagnerian harmonies in Scene 4's love duet notwithstanding.[27] First, Sibelius does not use recitatives; rather the work is entirely lyrical and melodic.[70] Second, although Sibelius gives themes to the Maiden (see first music example), the Bailiff, and the Lover (see second music example), he does not use Wagnerian leitmotif technique in the traditional sense, because these themes are not developed—either musically or psychologically—upon their returns.[70]

Finally, The Maiden in the Tower's small scale, in terms of both duration and instrumentation, is the antithesis of Wagnerian opera.[73] Instead, Sibelius may have taken as his model Pietro Mascagni's one-act opera Cavalleria rusticana (1890), the melodic, compact, and passionate nature of which had impressed him when he heard it performed in Vienna during the spring of 1891. According to Tawaststjerna, however, the Sibelius opera nevertheless "has greater symphonic unity" than its famous Italian counterpart.[50]

Context and analysis

[edit]

The plot as allegory

[edit]Several commentators have discerned within the plot of The Maiden in the Tower a possible allegory for the period's Russo-Finnish relations. This is part due to Sibelius's role in the 1890s as an artist at the center of the nationalist cause in Finland: he not only married into an aristocratic family identified with the Finnish resistance,[74] but also he joined the Päivälehti circle of liberal artists and writers.[75] "Opera was an obvious choice for giving wings to the spirit of national aspirations," Goss writes, "[And] the theme of an innocent maid cruelly incarcerated against her will offered the perfect subtext to the Finnish minded, who had been personifying their beloved country as 'the Maid of Finland' since 1890".[21] Read from this perspective, the story transforms: the Bailiff (Imperial Russia) abducts and imprisons the Maiden (the Grand Duchy of Finland); although she endures hardship, she remains true to herself and is freed subsequently (Finland's struggle for independence) by her Lover (Finnish nationalists)[76] and the Chatelaine (social reformers).[77][n] It is unclear, however, whether the simplicity of Hertzberg's libretto is evidence for or against an allegorical interpretation: while the music author Christopher Webber argues that the decision by Sibelius and Hertzberg to use "generic, nameless characters" indicates that they were more interested in political messaging than good storytelling.[77] The Sibelius biographer Andrew Barnett concedes Sibelius may have found the libretto too shallow to support a deeper meaning.[76][o]

Opera and Finland's language strife

[edit]From the 1870s to the 1890s, the politics of Finland featured a struggle between the Svecomans and the Fennomans. Whereas the former sought to preserve the privileged position of the Swedish language, the latter desired to promote Finnish as a means of inventing a distinctive national identity.[80][81] One goal of the Fennomans was to develop vernacular opera, which they believed to be symbolic of nationhood; to do so, they would need a permanent company with an opera house and a Finnish-language repertoire at its disposal.[82] Swedish-speaking Helsinki already had a permanent theatre company housed at the Swedish Theatre, and thanks to Fredrik Pacius, two notable, Swedish-language operas: King Charles's Hunt (Kung Karls jakt, 1852) and The Princess of Cyprus (Princessan af Cypern, 1860).[83][84][p] Success was hard-won: in 1872, the Fennoman Kaarlo Bergbom founded the Finnish Theatre Company, and a year later it named its singing branch the Finnish Opera Company. This was a small group that, without an opera house as residence, toured the country performing the foreign repertoire translated into Finnish. However, the Fennomans still remained without an opera written to a Finnish libretto, and in 1879 the Finnish Opera Company folded due to financial difficulties.[86]

Acting as a catalyst, in 1891 the Finnish Literature Society organized a competition that provided domestic composers with the following brief: submit before the end of 1896 a Finnish-language opera about Finland's history or mythology; the winning composer and librettist receive 2000 and 400 markka, respectively.[87] Sibelius had seemed an obvious candidate to inaugurate a new vernacular era, as he had become a favorite of the Fennomans with his Finnish-language masterpiece Kullervo, a setting of The Kalevala for soloists, male choir, and orchestra.[88] The competition was the impulse for The Building of the Boat, the 1893–1894 project in which Sibelius had aspired to write a mythological, Finnish-language Gesamtkunstwerk on the subject of Väinämöinen. But Sibelius abandoned this opera due to self-doubt and artistic evolution.[8] In the end, the Society received no submissions,[89] and when Sibelius finally emerged with his first opera, it was 1896's The Maiden in the Tower to a Swedish libretto. In its reviews, the Finnish-language press asked for Sibelius's next opera to be in the vernacular.[26][25][90][g]

Scholars have offered several explanations for the seeming conundrum that is The Maiden in the Tower's Swedish-language libretto. First, Hertzberg's selection as librettist probably guaranteed a story in Swedish; he was known not only for his Swedish-language historical novels and translations of Finnish folklore (including The Kalevala and excerpts from The Kanteletar),[66] but also for his longtime association with the Swedish-language press.[31][q] Second, Sibelius also was more comfortable with Swedish, his mother tongue.[92] For example, while composing Kullervo in 1891, his letters to his then-fiancée Aino Järnefelt detailed how difficult and unnatural he found the task of setting a Finnish text.[93][r] Third, there was little market for Finnish opera.[73] Domestically, the Finnish Opera Company remained disbanded and Helsinki was still without an opera house.[95][s] Internationally, Sibelius—as a composer who desired an international reputation—probably recognized that a Finnish-language opera would have little appeal in Germany, "the land of musical milk and honey".[92] Finally, the question may be misplaced. The lottery soirées were seen as a time for the nation, however internally divided over language, to unify against a common foe: Imperial Russia. As such, the evenings brought the feuding sides together under one roof and offered bilingual programming.[96] Indeed, not only was Sibelius's The Maiden in the Tower balanced during its premiere with the performance of a Finnish-language version of Bonsoir, Monsieur Pantalon!, an 1851 opéra comique by the Belgian composer Albert Grisar,[23] but afterwards, Yrjö Weilin was selected to translate Hertzberg's libretto into Finnish.[97][t]

Later opinions of Sibelius's music

[edit]Most commentators have viewed Sibelius's music positively. Hannikainen describes The Maiden in the Tower as an "early masterwork ... in spite of some weaknesses",[98] while the music critic David Hurwitz calls it a "slender but typically appealing effort ... [with] vocal writing throughout [that] is effective and confident".[99] The music journalist Vesa Sirén writes favorably that "the orchestration is skillful, the melodies are memorable, and there is enough dramatic fire in the setting".[18] Tawaststjerna argues that "Sibelius shows ... considerable talent for musical drama"; in particular, he cites the Maiden's part as "anticipat[ing his] 'great' solo songs", such as Autumn Evening (Höstkväll; Op. 38/1, 1904), On the Veranda by the Sea (På verandan vid havet; Op. 38/2, 1903), and Jubal (Op. 35/1, 1908).[50] "Considering that it is a first attempt," he continues, "The Maiden in the Tower has moments of unmistakable effectiveness ... as in the symphonies, Sibelius shows his command of musical movement and his capacity to build up a convincingly realized climax".[100]

Conversely, the musicologist and Sibelius biographer Cecil Gray posits that Sibelius's heart wasn't in The Maiden in the Tower: as a commissioned work, it lacks "any inner prompting or inclination ... it [is] completely negligible".[101] Similarly, the musicologist and Sibelius biographer Robert Layton writes that "deep inside him Sibelius must have recognized the truth that his was not an operatic talent ... [The Maiden in the Tower lacks] a sense of mastery ... it must be admitted that this is neither good opera nor good Sibelius". Nevertheless, Layton acknowledges the Maiden's prayer in Scene 2 and the chorus's spring music in Scene 3 are, respectively, "undoubtedly impressive" and "captivating and haunting".[102] Finally, the music critic Hannu-Ilari Lampila argues that, while The Maiden in the Tower "cannot be considered a masterpiece", it is nonetheless a "musically ... interesting" amalgam of "Sibelian national romanticism" and "frenetic accents of [Italian] verismo", especially the "earthy passions" of Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana.[103]

Reasons for post-1981 neglect

[edit]

Despite its resurrection in 1981, in the intervening decades Sibelius's opera has entered neither the Finnish or the international repertories, and performances have been rare.[104] The most common explanation for The Maiden in the Tower's neglect is the story's lack of appeal and the attendant risk of mounting a production.[18] Modern commentators have criticized Hertberg's libretto as "a lifeless concoction",[105] "bland",[106] "thinly-plotted",[18] "tarnished by naïveté",[102] and "startlingly silly ... its inanities on dreadful display from the opening lines".[21] While Tawaststjerna concedes that Hertzberg's libretto "as a whole is not without dramatically effective scenes",[12] he too registers a negative opinion, characterizing Hertzberg as a "mediocre author"[12] whose "simple" story was "embarrassingly awful... [an] operatic albatross that [Sibelius chose] to wear round his neck".[66]

Hannikainen posits a second explanation. He argues that The Maiden in the Tower has developed a poor reputation in part due to its "misleading" classification as an opera, because this label invites comparison with full-scale operas and thereby does Sibelius's small-scale work a disservice.[98] Evidence in support of this position includes: first, that Achté's letter asked Sibelius for a one-act stage work, not specifically an opera;[107] second, that the 1896 program advertised the piece as a "dramatized Finnish ballad";[108][a] third, that critics in 1896 struggled to categorize the new piece, describing it as an "opera", "operetta", "tableau", "ballad number", "short, opera-like composition", and "small, one-act play";[110] and fourth, that Sibelius—even if he had wanted—could not have written a full-scale opera, given the paltry orchestral and vocal resources at his disposal.[111][112] As such, The Maiden in the Tower might more fairly be categorized with and compared to Sibelius's other lottery music, such as 1893's Karelia or 1899's Press Celebrations Days.[113]

Discography

[edit]The Estonian-American conductor Neeme Järvi and the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra made the world premiere studio recording on 2 September 1983 for BIS Records.[114] In 2001, Paavo Järvi (Neeme's son) and the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra also recorded the opera. Critics have favored the more recent performance. In BBC Music Magazine, John Allison argues that, although The Maiden in the Tower "may not be top-drawer Sibelius", it nonetheless makes an "appreciable impact" in Paavo Järvi's "more compelling" interpretation.[115] Rob Barnett of MusicWeb International concurs, writing that "the music constantly intrigues and engages the listener"; the younger Järvi "makes this piece really sing", although the BIS recording benefits from the Finnish baritone Jorma Hynninen's "darker and huskier" vocal work as the Bailiff.[116] Critics have also praised Paavo Järvi's recording for the performance of the Norwegian soprano Solveig Kringelborn as the Maiden. For example, Allison writes that she "sings glowingly ... and is haunting in her prayer [Scene 2]",[115] while Andrew Achenbach of Gramophone applauds her for "cop[ing] valiantly with Sibelius's occasionally stratospheric demands ... [of] the heroine".[117] The table below lists all commercially available recordings of The Maiden in the Tower:[u]

| No. | Conductor | Orchestra | Bailiff | Maiden | Lover | Chatelaine | Choir | Rec.[v] | Time | Recording venue | Label | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neeme Järvi | Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra | Jorma Hynninen | MariAnn Häggander | Erland Hagegård | Tone Kruse | Gothenburg Concert Hall Choir | 1983 | 35:15 | Gothenburg Concert Hall | BIS | |

| 2 | Paavo Järvi | Estonian National Symphony Orchestra | Garry Magee | Solveig Kringleborn | Lars-Erik Jonsson | Lilli Paasikivi | Ellerhein Girls' Choir Estonian National Male Choir |

2001 | 36:39 | Estonia Concert Hall | Virgin Classics |

Notes, references, and sources

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b The original Swedish is: "dramatiserad finsk ballad"; the original Finnish is: "dramatisoitu suomalainen ballaadi".[109]

- ^ a b The 12-minute Concert Overture is distinct from the overture of the opera, the duration of which is three minutes.

- ^ Hannikainen provides a slightly different name, Neito istuu kammiossa, for the folk ballad.[16]

- ^ Tawaststjerna misreports the date of the opera's premiere as 9 November 1896 in both his biography of Sibelius and his liner notes to 1983's BIS recording.[19][12]

- ^ a b Some sources incorrectly list the name of the tenor who originated the role of the Lover as "Engström". According to newspaper accounts, the vocalist was "E. Eklund".[20][23]

- ^ Also on the program was: Bonsoir, Monsieur Pantalon!, an 1851 opéra comique by the Belgian composer Albert Grisar (translated into Finnish); three special admission tableaux in the Sofia Room arranged by the Finnish artist Albert Edelfelt; and Salome's Dance ("Herodias dans" on the program), performed by Ingrid Silfverhjelm to Kaarlo Bergbom's "brilliant" choreography and Camille Saint-Saëns's Danse de la Gipsy from act 2 of the 1883 opera Henry VIII (Kajanus conducting).[23] This "spectacular" tableau stole the show and was twice encored.[22][20][23]

- ^ a b The first opera to a Finnish libretto belongs to Oskar Merikanto, who composed The Maiden of the North (Pohjan neiti) in 1898 in response to the Finnish Literature Society's second competition. Being the only submission, The Maiden of the North won by default; it remained unperformed until its premiere at the 1908 Vipurii Song Festival.[91]

- ^ a b c This article uses the Finnish name for municipalities in Finland; the Swedish name provided parenthetically.

- ^ Tawaststjerna notes a request by Ackté to revive The Maiden in the Tower at the Savonlinna Opera Festival, which she had founded in 1912.[27] However, he cites no sources and Hannikainen does not mention this event.

- ^ The Maiden in the Tower concert overture was a late substitute for The Swan of Tuonela. Hannikainen offers two reasons why Sibelius might have made the change. First, on 13 February 1900, Sibelius's third child, Kirsti (born 14 November 1898)[42] had died of typhus; her "death was a terrible blow to him ... his grief was so marked that he never spoke of her again".[43] Under such circumstances, Sibelius may have found The Swan of Tuonela's mournful music uncongenial.[44] Second, the period 1899–1900 found Sibelius returning to, and revising, his earlier works in anticipation of the Helsinki Philharmonic Society's Finnish music concert at the 1900 Paris Exposition, during which his music would feature. Sibelius might have resurrected The Maiden in the Tower for this purpose, with the Turku concerts providing him the opportunity to test its effectiveness as a concert item.[44] In the end, Sibelius was represented at the event by: Finlandia, the First Symphony, The Swan of Tuonela and its companion piece Lemminkäinen Returns, and the King Christian II Suite.[45][46]

- ^ a b Although The Maiden in the Tower is scored for a contralto soloist, a mezzo-soprano may substitute.

- ^ In 2001, the Finnish soprano Karita Mattila recorded the Maiden's aria as a stand-alone orchestral song for Warner Classics (8573 80243–2), with Sakari Oramo conducting the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

- ^ The Chatelaine is a dea ex machina.[12][61]

- ^ Hertzberg advocated for women's equality, and his views likely found expression in the Chatelaine's role.[78]

- ^ If The Maiden in the Tower is allegorical, then it would join other works by Sibelius that fit a similar theme: the melodrama Snöfrid (Op. 29, 1900) and the cantata The Captive Queen (Vapautettu kuningatar) (Op. 48, 1906).[79]

- ^ A third Swedish-language opera is The Junker's Guardian (Junkerns förmyndare), written in 1853 by the Finnish composer Axel Gabriel Ingelius. However, it was never performed and only partially survives. Finally, in 1887, Fredrik Pacius composed his final opera, Loreley (Die Loreley), to a German-language libretto.[85]

- ^ Hertzberg had been the editor, theatre and art critic, and literary reporter of Helsingfors Dagbladet from 1875 to 1889, and had also contributed to Finsk Tidskrift and Hufvudstadsbladet in the 1890s.[31][30]

- ^ Hannikainen disputes this explanation, arguing that Sibelius had made great strides with Finnish by 1896.[94]

- ^ Permanent, bilingual operatic activity would not begin until 1911 with the founding of the Domestic Opera.[95]

- ^ Weilin's translation never materialized, presumably because Sibelius withdrew the opera. In 1906, Sibelius gave Jalmari Finne permission to translate the libretto, but the plans fell through.[97]

- ^ Although Jussi Jalas never made a studio recording of The Maiden in the Tower, Voce Records released a pirated LP of his 28 January 1981 performance.[104] It last 37:18 minutes.

- ^ Refers to the year in which the performers recorded the work; this may not be the same as the year in which the recording was first released to the general public.

- ^ N. Järvi–BIS (CD–250) 1984

- ^ P. Järvi–Virgin (7243 5 45493 2 8) 2002

- References

- ^ Dahlström 2003, p. 560.

- ^ Dahlström 2003, pp. 556–559.

- ^ Dahlström 2003, p. 559.

- ^ Gray 1934, p. 92; Goss 2009, p. 231.

- ^ Grimley 2021, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Hannikainen 2020, p. viii.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 29.

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 141–143, 158–160.

- ^ Barnett 2007, pp. 83, 88, 94–95, 101–103.

- ^ Goss 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Hannikainen 2020, p. ix.

- ^ Goss 2009, pp. 231, 472.

- ^ Hannikainen 2020, pp. viii–ix.

- ^ a b Hannikainen 2020, p. i.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 184.

- ^ a b c d Sirén.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 189.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Nya Pressen, No. 305 1896, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Goss 2009, p. 231.

- ^ a b Goss 2009, p. 233.

- ^ a b c d e Hufvudstadsbladet, No. 305 1896, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Nya Pressen, No. 314 1896, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Päivälehti, No. 262 1896, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Uusi Suometar, No. 261 1896, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 6.

- ^ a b Barnett 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 59, 163.

- ^ a b Hufvudstadsbladet, No. 333 1896, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Hannikainen 2018, p. 32.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Hannikainen 2020, p. xii.

- ^ Hannikainen 2020, p. xi.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d Heikinheimo 1981, p. 18.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 167.

- ^ a b c Hannikainen 2020, p. x.

- ^ a b Avanti! 2021.

- ^ a b Uusi Aura, No. 82 1900, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Åbo Underrättelser, No. 96 1900, p. 2.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 224.

- ^ a b Hannikainen 2020, p. iv.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 225, 231.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 135.

- ^ Hannikainen 2020, pp. x–xii.

- ^ a b c Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 20–26.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 5.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 22.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Hannikainen 2020, pp. x–xi.

- ^ Barnett 2007, p. 108.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 20.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 24.

- ^ Webber 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 25.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Edition Wilhelm Hansen 1995.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 186.

- ^ Edition Wilhelm Hansen 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 186–188.

- ^ a b c Tawaststjerna 2008, p. 188.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Edition Wilhelm Hansen 1995, p. 101.

- ^ a b Hurwitz 2007, p. 173.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Barnett 2007, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Webber 2011, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Barnett 2007, pp. 139–140, 175–176.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Goss 2009, pp. 39, 117, 135–136, 144, 192.

- ^ Hautsalo 2015, pp. 181, 185.

- ^ Hautsalo 2015, p. 181.

- ^ Korhonen 2007, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Korhonen 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Hautsalo 2015, pp. 175, 182.

- ^ Päivälehti, No. 274 1891, p. 4.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 100, 102–103, 106.

- ^ Ketomäki 2017, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 118.

- ^ Ketomäki 2017, p. 269.

- ^ a b Goss 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 42, 72, 76.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 120.

- ^ a b Hautsalo 2015, p. 176.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 119, 121.

- ^ a b Hannikainen 2018, p. 119.

- ^ a b Hannikainen 2018, p. 11.

- ^ Hurwitz 2007, pp. 173, 175.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 187, 189.

- ^ Gray 1934, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Layton 1993, p. 125.

- ^ Lampila 1981, p. 47.

- ^ a b Hannikainen 2018, p. 20.

- ^ Viking 1993, p. 983.

- ^ Korhonen 2007, p. 44.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 11, 18.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, p. 18.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 144–144.

- ^ Goss 2009, pp. 192, 232.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Hannikainen 2018, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Tawaststjerna 1984, p. 27.

- ^ a b Allison 2012.

- ^ Barnett 2008.

- ^ Achenbach 2002.

- Sources

- Books

- Sibelius, Jean (1995) [1896]. The Jungfrun i Tornet [The Maiden in the Tower] (in Swedish and German). Edition Wilhelm Hansen. ISBN 9788759860830. HL.14017415.

- Barnett, Andrew (2007). Sibelius. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16397-1.

- Dahlström, Fabian [in Swedish] (2003). Jean Sibelius: Thematisch-bibliographisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke [Jean Sibelius: A Thematic Bibliographic Index of His Works] (in German). Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 3-7651-0333-0.

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (2009). Sibelius: A Composer's Life and the Awakening of Finland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-00547-8.

- Gray, Cecil (1934) [1931]. Sibelius (2nd ed.). London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 373927.

- Grimley, Daniel (2021). Jean Sibelius: Life, Music, Silence. Reaktion Books. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-78914-466-6. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Hannikainen, Tuomas [in Finnish] (2018). Neito tornissa: Sibelius näyttämöllä [The Maiden in the Tower: Sibelius on Stage] (D.Mus) (in Finnish). Helsinki: Sibelius Academy, the University of the Arts Helsinki. ISBN 978-9-523-29103-4.

- Hautsalo, Liisamaija (2015). "Strategic Nationalism Towards the Imagined Community: The Rise and Success Story of Finnish Opera". In Belina-Johnson, Anastasia; Scott, Derek (eds.). The Business of Opera. London: Routledge. pp. 191–210. ISBN 978-1-315-61426-7.

- Holden, Amanda; Kenyon, Nicholas; Walsh, Stephen, eds. (1993). The Viking Opera Guide. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-81292-7.

- Hurwitz, David (2007). Sibelius: The Orchestral Works—An Owner's Manual. (Unlocking the Masters Series, No. 12). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-574-67149-0.

- Ketomäki, Hannele (2017). "The Premiere of Pohjan neiti at the Vyborg Song Festival, 1908". In Kauppala, Anne; Broman-Kananen, Ulla-Britta; Hesselager, Jens (eds.). Tracing Operatic Performances in the Long Nineteenth Century: Practices, Performers, Peripheries. Helsinki: Sibelius Academy. pp. 269–288. ISBN 978-9-523-29090-7.

- Korhonen, Kimmo [in Finnish] (2007) [2003]. Inventing Finnish Music: Contemporary Composers from Medieval to Modern. Translated by Mäntyjärvi, Jaakko [in Finnish] (2nd ed.). Jyväskylä, Finland: Finnish Music Information Center (FIMIC) & Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. ISBN 978-9-525-07661-5.

- Layton, Robert (1993) [1965]. Sibelius. (The Master Musicians Series) (4th ed.). New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0028713222.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (2008) [1965/1967; trans. 1976]. Sibelius: Volume I, 1865–1905. Translated by Layton, Robert. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24772-1.

- Wilker, Ulrich (2021). "In the Lab with Wagner: Jean Sibelius's Jungfrun i tornet (JS 101) as Experiment". In Kauppala, Anne; Knust, Martin (eds.). Wagner and the North. Helsinki: Sibelius Academy. pp. 377–391. ISBN 978-952-329-158-4.

- Liner notes

- Hannikainen, Tuomas, ed. (2020). "Esipuhe" [Preface]. Konserttialkusoitto [Concert Overture] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Fennica Gehrman. p. i–vii. ISMN 979-0-55011-734-1. KL 78.52.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1984). Jean Sibelius: The Maiden in the Tower, opera in one act / Karelia Suite, Op. 11 (CD booklet). Neemi Järvi & Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra. BIS. p. 4–6. CD–250. OCLC 21810287

- Webber, Christopher (2011). Ladies in High Places: Two Operatic Towers (Concert program). Buxton, England: Buxton Festival 2012. p. 1–5.

- Newspapers (by date)

- "Kilpapalkinto Suomalaista oopperaa varten" [Competition prize for a Finnish opera]. Päivälehti (in Finnish). No. 274. 25 November 1891. p. 4.

- "Lotteriet till förmån for Filharmoniska sällskapet" [The lottery in favor of the Philharmonic Society]. Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish). No. 305. 8 November 1896. p. 5.

- "Eiliset arpajaishuvil Filharmoonisen seura hyväksi" [Yesterday's raffle in favor of the Philharmonic Society]. Uusi Suometar (in Finnish). No. 261. 8 November 1896. p. 2.

- Felicien (8 November 1896). "Lotteriet för orkestern" [A lottery for the orchestra]. Nya Pressen (in Swedish). No. 305. p. 3.

- O. [Merikanto, Oskar] (9 November 1896). "Jean Sibeliuksen ooppera "Jungfrun i tornet"" [Jean Sibelius's opera "The Maiden in the Tower"]. Päivälehti (in Finnish). No. 262. p. 2.

- K. [Flodin, Karl] [in Finnish] (17 November 1896). "J. Sibelius Jungfrun i tornet" [J. Sibelius The Maiden in the Tower]. Nya Pressen (in Swedish). No. 314. p. 3.

- A. S. (6 December 1896). "Rafäel Hertzberg [död]" [Rafael Hertzberg [dead]]. Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish). No. 333. p. 6.

- "Jean Sibeliuksen säwellys-konsertti" [Jean Sibelius's composition concert]. Uusi Aura (in Finnish). No. 82. 8 April 1900. p. 3.

- "Jean Sibelius' kompositionskonsert" [Jean Sibelius's composition concert]. Åbo Underrättelser (in Swedish). No. 96. 8 April 1900. p. 2.

- Heikinheimo, Seppo [in Finnish] (28 January 1981). "Sibeliuksen ooppera vuodelta 1896 esiin" [Sibelius's opera from 1896 out in the open]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). p. 18.

- Lampila, Hannu-Ilari [in Finnish] (28 January 1981). "Sibeliuksen ainokainen ooppera ensiesitettiin arpajaisjuhlissa" [Sibelius's sole opera saw its premiere at a lottery draw event]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). p. 47.

- Websites

- "Avanti! conducted by Tuomas Hannikainen resurrects Sibelius work dormant for 120 years". avantimusic.fi. Avanti!. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- Achenbach, Andrew (2002). "The Maiden in the Tower makes its second and finest appearance on disc". erso.ee. Gramophone. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Allison, John (2012). "Sibelius: The Maiden in the Tower; Pelléas et Mélisande (incidental music); Valse triste". classical-music.com. BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Barnett, Rob (2008). "Sibelius: The Maiden in the Tower P. Järvi". musicweb-international.com. MusicWeb International. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Sirén, Vesa [in Finnish]. "Incidental music: Jungfrun i tornet (The Maiden in the Tower), one-act opera". sibelius.fi. Finnish Club of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

![{\new PianoStaff {<<\new Staff \relative c'{\set Staff.midiInstrument=#"string ensemble 1" \time 2/4 \tempo "Allegro molto" \clef treble ^"Violins" |(b16\p[gis'16)] 4~ 8-.|gis16[(bis,16]) 4~ 8-.|bis16[(gis'16)] 4~ 8-.|gis16[(cis,16]) 4~ 8-.|cis8[(e8)] 8-. ( 8-.)|4(b8) 8|4(cis8)[dis8]|cis2:16|2:16|} \new Staff \relative c'{\set Staff.midiInstrument=#"bassoon" \time 2/4 \clef bass ^"Bassoon" |e,,2~\p|2~|2~|4 r4|cis'8[(e8)] 8 8|4(b8) 8|4(cis8)[dis8]|cis2~|2|}>>}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/n/dnuc9f0b5pmvfn6lk6vxvm5nyj59jt6/dnuc9f0b.png)

![{\new Staff \relative c'{\set Staff.midiInstrument=#"flute" \numericTimeSignature \time 2/2 \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo "Allegro moderato" 4=150 \clef treble \key bes \major ^"Flute" |f'2(\ppp g4 d4|f2 d4 c4)|f2(g4 d4 f2.)|4~(2 g4 d4|f2 d4 c4|f4) 4(g4 d4|f2.) 4(|\break bes4 g4 f4 g4|f2.~<< { 4-.)|r1|r2 r4 \set Staff.midiInstrument=#"flute" \relative c'' {\transposition c' f4--}} \new CueVoice {\set Staff.midiInstrument=#"clarinet" \relative c'' {\transposition bes \once \override NoteColumn.force-hshift = #1.3 g'4^"Clarinet"(\ppp|c4 a4 g4 a4|g1)}}>>~\set Staff.midiInstrument=#"flute"|bes4(g4 f4 g4|a4) d,8^\markup {\italic "grazioso"} ([e8] d8[e8 d8 e8]|f4) d4(c4 f,4)|bes4(d4 g4 d4)|}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/x/4xz99m0nb2spvgem1j51wokct46cpk6/4xz99m0n.png)