Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis

| Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis | |

|---|---|

Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis at the Verdun Memorial, Fleury-devant-Douaumont, France | |

| Type | Medium trench mortar |

| Place of origin | France |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1915–1916 |

| Used by | France Kingdom of Italy |

| Wars | World War I |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Commandant du Génie Duchêne Général de Brigade Jean Dumézil |

| Designed | 1914-1915 |

| Manufacturer | Manufacture d'armes de Saint-Étienne |

| No. built | 1,700 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 181 kg (399 lb) |

| Length | 550 mm (1 ft 10 in) |

| Crew | 5 |

| Shell | Separate loading bagged charge and projectile |

| Shell weight | 16 kg (35 lb) |

| Calibre | 58.3 mm (2.3 in) (barrel only) |

| Recoil | None |

| Elevation | +45° to +80° |

| Traverse | 60° |

| Rate of fire | 1 rpm |

| Muzzle velocity | 65–73 m/s (210–240 ft/s) |

| Maximum firing range | 450 m (490 yd) at +45° |

| Filling | Melinite |

| Filling weight | 6 kg (13 lb) |

Detonation mechanism | Contact fuze[1] |

The Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis sometimes referred to as Lance Torpilles was an early French medium trench mortar. It was used by both the French Army and Italian Army during the First World War.

Background

[edit]The majority of military planners before the First World War were wedded to the concept of fighting an offensive war of rapid maneuver which before mechanization meant a focus on cavalry and light horse artillery firing shrapnel shells at formations of troops in the open. The problem facing the combatants was that their light field guns were designed for direct fire and only had limited angles of elevation and weren't capable of providing the high-angle indirect fire needed to deal with enemy troops in dug-in positions.[2]

The simple expedient was to elevate the guns by having them fire from pits but the size and weight of the guns were excessive and pack animals couldn't move the guns in the trenches or across the shell-pocked quagmire of no man's land. What the theorists hadn't foreseen was that land mines, trenches, barbed wire, and machine guns would rob them of mobility and as the Western Front stagnated into trench warfare the light field guns that the combatants went to war with began to show their limitations.[2]

Often defenders would wait out a preparatory artillery bombardment in reinforced dugouts and once the bombardment had lifted they would man their trenches and machine-gun nests in anticipation of an enemy attack across no man's land. Barbed wire was often used to channel attackers away from vulnerable areas of the defender's trenches and funnel attackers into predefined kill zones where overlapping fields of machine-gun fire could be brought to bear or to hold attackers at a safe distance to call in defensive artillery fire. The machine-gun nests could be constructed of sandbags, timber, corrugated metal, and concrete with overhead protection. For infantry advancing across no man's land, all they may see is a small horizontal opening at waist level, with just the top of the gun shield showing. Attacking infantry would have to close on these positions while under fire and destroy them with rifle fire, grenades, and flamethrowers.[3]

The problem for the French Army was they lacked light, portable, simple, and inexpensive firepower that could be brought with them to overcome enemy machine gun nests and wire entanglements. Early on they experimented with crossbows, catapults, and slingshots to propel hand grenades with limited success. Unlike the Germans the French lacked portable mortars like the 7.58 cm Minenwerfer, 17 cm mittlerer Minenwerfer or 25 cm schwere Minenwerfer. The mortars that the French did have the Obusier de 155 mm C modèle 1881 and Mortier de 220 mm modèle 1880 were siege artillery designed to arm France's forts that were much heavier than their opponents and not designed to be mobile.[4]

History

[edit]In 1914, Major Duchêne of the Engineers (of the 33rd Corps belonging to X Army) began experimenting with a simple improvised tube mortar made from discarded Canon de 75 mle 1897 cases at the end of a pole. He found he was able to build a simple high-explosive fragmentation projectile that could be used as an anti-personnel weapon and to clear barbed wire entanglements. On November 7, 1914, Commander Duchêne was sent to the Bourges pyrotechnics school by order of General Joseph Joffre to develop a mortar under the direction of General Dumézil, inspector of artillery studies and testing.[5]

The basic specification was for a light, mobile, and inexpensive mortar which could fire a 10 kg (22 lb) projectile to a range of 200 m (220 yd) using a smokeless powder propellant charge. The requirement also specified a weapon that could be produced from non-strategic materials, using simple production methods and produced by companies not currently engaged in war work.[5]

The first 70 mortars were delivered in mid-January 1915 to troops in the Argonne region for testing. The tests were considered successful and General Joffre ordered another 110 mortars and the production of 4,000 projectiles a day. However, the tests revealed that the launcher was unstable and had a tendency to tip over when pulling on the firing lanyard. The launcher often fell over after being fired and had to be re-aimed between shots which limited its rate of fire. The troops also requested heavier projectiles with larger explosive charges to deal with enemy troops in dug-in positions and these factors led to the Mortier de 58 T N°1 being replaced in 1916.[5]

Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis and Mortier de 58 T N°2

[edit]To address deficiencies in the design of the Mortier de 58 T N°1 Major Duchêne continued to work on the design of two new mortars concurrently with completely different bases. Where the N°1 was tall, thin, and top-heavy the N°1 bis and N°2 launchers were short, had a broad footprint, and low center of gravity. The long launch tube wasn't needed to elevate the projectiles past the lip of the trench so a shorter and sturdier launch tube was used instead. Both designs were much more stable which led to a higher rate of fire because they didn't need as much setup time between shots. Their short and fat appearance earned them the nickname "little toads".[6]

The Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis were lighter than the Mortier de 58 T N°2 and weighed 181 kg (399 lb) and could fire the same projectiles as the Mortier de 58 T N°1 to 450 m (490 yd) at +45°. The mortar consisted of a square metal baseplate with four hoops at the corners that two wooden poles slid through so the crew to carry the assembled mortar. There was a short smoothbore barrel that sat on a circular metal swivel that could be adjusted for both traverse and elevation. Once traverse and elevation were set there were handles to lock the swivel in place. The 37–57 g (1–2 oz) propellant charge was then inserted in the muzzle and the projectile slid onto the end of the barrel. The mortar was fired by pulling on a lanyard which was attached to a friction igniter embedded in the propellant. However, the projectiles were considered too light and the Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis were in turn replaced by the Mortier de 58 T N°2. The advantage of the Mortier de 58 T N°2 was that it could fire new heavier projectiles of similar design to a greater range but it weighed 410 kg (900 lb) so it wasn't as mobile.[6]

Both the Mortier de 58 T N°2 and Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis were used by the Italian Army who gave the Mortier de 58 T N°2 the designation Bombarda da 58 A and the Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis was designated Bombarda da 58 B. Approximately 1,000 of both types were used by the Italian Army.[7]

Gallery

[edit]-

The earlier Mortier de 58 T n°1 near Vauquois, France, 1915

-

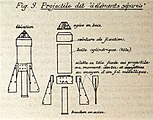

Diagram of the projectile

-

A loaded Mortier de 58 T n°1 bis

-

The Mortier de 58 T n°1 bis is to the left and the later Mortier de 58 T N°2 is to the right

-

A group of Allied officers. A three-finned Mortier de 58 T n°1 is to the left and a six-finned Mortier de 58 T n°2 is to the right.

References

[edit]- ^ "Mortier de 58 T N°1 bis". www.passioncompassion1418.com. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ a b Batchelor, John (1979). Land power. John H. Batchelor. New York: Exeter Books. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-89673-010-7. OCLC 5718938.

- ^ Batchelor, John (1979). Land power. John H. Batchelor. New York: Exeter Books. pp. 30–34. ISBN 0-89673-010-7. OCLC 5718938.

- ^ "Les Français à Verdun - 1916". www.lesfrancaisaverdun-1916.fr. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ a b c "Les mortiers de 58 de tranchée". artillerie.asso.fr. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ^ a b "Le Crapouillot". Batterie de l'Eperon - Frouard (in French). 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ Cappellano, Filippo (2005). I bombardieri del re : la storia e l'armamento del corpo dei bombardieri della grande guerra. Bruno Marcuzzo. Udine: P. Gaspari. p. 45. ISBN 88-7541-092-5. OCLC 62597980.