Canon de 370 modèle 75/79 Glissement

| Canon de 370 modèle 75/79 Glissement | |

|---|---|

A mle 1877/79 captured from the Germans. | |

| Type | Railway gun |

| Place of origin | France |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1918–1945 |

| Used by | |

| Wars | World War I World War II |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Schneider |

| Designed | 1917 |

| Manufacturer | Schneider |

| Produced | 1918-1919 |

| No. built | 6 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 250 t (250 long tons; 280 short tons) |

| Length | 33.2 m (109 ft) |

| Barrel length | 10.36 m (34 ft) L/28[1] |

| Shell | Separate loading bagged charge and projectile |

| Shell weight | 700 kg (1,500 lb) |

| Caliber | 370 mm (15 in)[1] |

| Breech | Interrupted screw breech |

| Recoil | Sliding recoil mount |

| Carriage | Two eight-axle articulated rail bogies. |

| Elevation | +3° to +40° |

| Traverse | None[1] |

| Rate of fire | 1 round every four minutes |

| Muzzle velocity | 745 m/s (2,440 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 23 km (14 mi) at +40°[1] |

The Canon de 370 modèle 75/79 Glissement was a French Railway gun designed during World War I but produced too late to see action during the war. The six guns built were held in reserve between the wars and were not mobilized by France during World War II.

History

[edit]Although the majority of combatants had heavy field artillery prior to the outbreak of the First World War, none had adequate numbers of heavy guns in service, nor had they foreseen the growing importance of heavy artillery once the Western Front stagnated and trench warfare set in. Since aircraft of the period were not yet capable of carrying large diameter bombs the burden of delivering heavy firepower fell on the artillery. Two sources of heavy artillery suitable for conversion to field use were surplus coastal defense guns and naval guns.[1]

However, a paradox faced artillery designers of the time; while large caliber naval guns were common, large caliber land weapons were not due to their weight, complexity, and lack of mobility. Large caliber field guns often required extensive site preparation because the guns had to be broken down into multiple loads light enough to be towed by a horse team or the few traction engines of the time and then reassembled before use. Building a new gun could address the problem of disassembling, transporting and reassembling a large gun, but it did not necessarily address how to convert existing heavy weapons to make them more mobile. Rail transport proved to be the most practical solution because the problems of heavy weight, lack of mobility and reduced setup time were addressed.[1]

Design

[edit]The mle 75/79 started life as Canon de 370 modèle 1875/1879 naval guns which were the primary armament of the two Amiral Baudin-class ironclads of the French Navy. The guns were typical built-up guns of the period with several layers of steel reinforcing hoops. The guns used an interrupted screw breech and fired separate loading bagged charges and projectiles. To load the gun barrel was lowered and a shell was brought forward by an elevated hoist on the rear of the carriage.[2]

The guns consisted of a large rectangular steel base, which was suspended on two eight-axle articulated rail bogies manufactured by Schneider. The number of axles was determined by the weight limit for European railways of 17 tonnes per axle.[1] The carriage was similar to that used by the contemporary Obusier de 520 modèle 1916 produced by Schneider. Since the carriage did not have a traversing mechanism it was aimed by drawing the guns across a section of curved track. Once in firing position, a section of rail bed was reinforced with wood and iron beams to support the weight of the gun. Five steel beams under the center of the carriage were then lowered to lay across the tracks and the carriage was jacked up to take weight off the bogies and anchor the gun in place. There were another two beams located between the quadruple bogies on each end of the carriage.[2] When the gun fired the entire carriage recoiled a few feet and was stopped by the friction of the beams on the tracks. The carriage was then lowered onto its axles and was either pushed back into place with a shunting locomotive or a windlass mounted on the front of the carriage pulled the carriage back into position. This cheap, simple and effective system came to characterize Schneider's railway guns during the later war years and is known as the Glissement system.[2]

Comparison to other French heavyweight guns

[edit]- Unlike the earlier Obusier de 370 modèle 1915 and Obusier de 400 Modèle 1915/1916 the barrels for the mle 75/79 were not shortened or bored out to 370 mm (15 in).

- The mle 75/79 were classified as cannons rather than howitzers so their maximum elevation of +40° gave their projectiles a different trajectory.

- The mle 75/79 had higher muzzle velocity 745 m/s (2,440 ft/s) and greater range 23 km (14 mi) than either of the previous two howitzers mentioned.

- Due to the greater weight of the mle 75/79 250 t (250 long tons; 280 short tons), its carriage was longer and more elaborate than previous railway guns. In order to distribute this weight, there were more axles and the bogies were articulated to reduce stress on the tracks.

- The ammunition hoists, shell rammers, and elevation controls were all electrically powered and according to Railway Artillery, vols. I and II they may have not been reliable enough to withstand the stress of firing.[2]

World War I

[edit]The six guns were delivered too late to participate in the First World War and remained in reserve between the wars.

World War II

[edit]At the outbreak of the Second World War the six guns remained in reserve and were not mobilized. The Germans assigned the designation 37cm H(E) 714(f) but what use they made of them is unknown.

Gallery

[edit]-

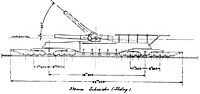

A mle 1875-1879, on Schneider sliding railway mounting.

-

French railway guns captured after the Fall of France.

-

A mle 1875/79 captured from the Germans.

-

A mle 1875/79 with a damaged barrel captured from the Germans.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Hogg, Ian (2004). Allied artillery of World War One. Ramsbury: Crowood. pp. 129–134 & 218. ISBN 1861267126. OCLC 56655115.

- ^ a b c d Miller, H. W., LTC, USA (1921). Railway Artillery, vols. I and II. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 108–109.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)