Lake Hiawatha, New Jersey

Lake Hiawatha, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

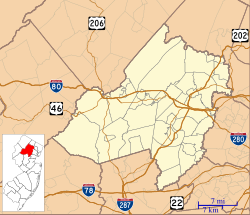

Location in Morris County Location in New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 40°52′57″N 74°22′54″W / 40.88250°N 74.38167°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Morris |

| Township | Parsippany-Troy Hills |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.11 sq mi (2.88 km2) |

| • Land | 1.10 sq mi (2.86 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) |

| Elevation | 253 ft (77 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 10,194 |

| • Density | 9,233.70/sq mi (3,565.89/km2) |

| ZIP Code | 07034 |

| FIPS code | 34-37680[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0877634[4] |

Lake Hiawatha is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP)[5] located within Parsippany–Troy Hills Township in Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[6] The U.S. Postal Service serves the community as ZIP Code 07034. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,194.[2]

Lake Hiawatha was named after Hiawatha, a 16th-century Native American leader and peacemaker, as evident by plaques on the gazebo on Beverwyck Road, the name of its park, and in the name and emblem of its fire department. However, its name was likely inspired by the popularity of The Song of Hiawatha, an 1855 poem by Longfellow which has little to no correlation with the historical figure of Hiawatha.

History

[edit]Pre-colonial history

[edit]Lake Hiawatha is part of the Lenapehoking, the traditional territory of the Munsee subtribe of the Lenape tribe. Lenape tribes inhabited the lands for thousands of years prior to European arrival.

Beverwyck plantation

[edit]Beverwyck Road is the central road that divides downtown Lake Hiawatha, containing the majority of its small businesses,[7] and leads to U.S. Route 46.[8] The road was named for the 2,000-acre (810 ha) Beverwyck plantation, a slave plantation which was in operation from the 1730s to the early 1800s.[9] The estate's owners included William Kelly, Abraham Lott, and Lucas Von Beverhoudt. It was also called "Beaverwyck", "Beaverwick", and the "Red Barracks".[10]

In 1768, a newspaper advertisement for the property mentioned a "Negro House" which was constructed to house over 20 enslaved workers, including a blacksmith, a shoemaker, and a mason.[10][11] In 1780, Von Beverhoudt posted a newspaper notice providing a description to re-capture "Jack", a "runaway slave"; this notice is on file at the Morristown National Historical Park.[10]

Phebe Ann Jacobs (1785–1850) was "born a slave" on the Beverwyck plantation.[12] As a child, she was "given to"[12] Maria Malleville, the daughter of President Wheelock of Dartmouth College. In 1820, Maria Malleville married President Allen of Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. Jacobs remained with the family until the death of Maria Allen, from which time she chose to live alone. For the last years of her life, she was free in Maine, laundering clothes for students of Bowdoin. Mrs. T. C. Upham, the wife of a theology professor at Bowdoin, met Jacobs and wrote the biography of her life. Jacobs died in Brunswick, February 28, 1850.[12] In 1850, Upham published the biography titled Narrative of Phebe Ann Jacobs in London.[12] The book demonstrated Jacobs's lifelong devotion to Christianity. The biography served as inspiration for author Harriet Beecher Stowe as she wrote her 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin.[13]

During the Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1783, Beverwyck Road was known as "Washington's Trail",[7] and was often traversed by French and Continental armies en route to Morristown.[8]

Visitors entertained at the Beverwyck plantation include George Washington, Nathaniel Greene, and the Marquis de Lafayette.[9]

Addition of lake

[edit]In the 1920s, developers began building the community, focusing on summer houses. By 1932, the built environment was complete and houses were settled. North Beverwyck Road, Dacotah Avenue and Nokomis Avenue were the only streets available.[14]

The lake was completed in 1935. Developers redirected the Rockaway River into a lake and used the shoreline to construct summer houses and a meeting house for its country club. The lake was meant as the center of summer activity, consisting of an artificial beach with white sand, a pavilion, a playground, and an area for barbecues.[14]

In January 1935, a fire destroyed a home on Wenonah Avenue in Lake Hiawatha. As a response, six men founded the volunteer-based Lake Hiawatha Fire Department in a basement. Their first meeting was held at the clubhouse in February. The town could only afford three backpacks of galvanized fire pumps (a.k.a. "Indian pumps"). The new department's goal was to raise funds for the purchase of more substantial firefighting equipment. Several fundraisers were held in 1935. First, the fire department hosted a professional boxing match that cost 50¢ for general admission and 75¢ for ringside. In 1935, the firefighters organized and performed a minstrel show fundraiser,[14] a type of stage performance based on racist Black caricatures. Circa 1935, minstrel shows were predominantly amateur theater, continuing to perform slavery-focused musical skits of the Antebellum era, circa 1850s.[15] An audience of 414 attended the show; donations and ticket sales provided enough money for the purchase of the first fire engine.[14] In August 1935, the fire department purchased their first fire engine, a 1913 American LaFrance.[14]

In 1948, Benjamin J. Kline donated the funds required to create the Lake Hiawatha Public Library.[16]

By the 1960s, the lake had dried up and the cabins were rebuilt into year-round homes.[17]

Geology

[edit]The area was created when a chain of volcanic islands collided with the North American plate. The islands went over the North American plate and created the highlands of New Jersey. Then around 450 million years ago, a small continent collided with proto North America and created folding and faulting in western New Jersey and the southern Appalachians. When the African plate separated from North America, this created an aborted rift system or half-graben. The land lowered between the Ramapo fault in western Parsippany–Troy Hills and the fault that was west of Paterson.

The Wisconsin Glacier covered the area from 21,000 to 13,000 BC. When the glacier melted due to climate change, Lake Passaic was formed, covering all of what is now Lake Hiawatha. Lake Passaic slowly drained, and much of the area is swamps or low-lying meadows such as Troy Meadows. The Rockaway River flows over the Ramapo fault in Boonton and then flows along the northwestern edge of Lake Hiawatha. In this area, there are swamps near the river or in the area.

Geography

[edit]Lake Hiawatha is in eastern Morris County, in the northeastern part of Parsippany–Troy Hills Township. It is bordered to the south by the Parsippany CDP and to the northeast by Montville Township, including part of the community of Pine Brook. It is 3 miles (5 km) southeast of Boonton, 9 miles (14 km) northeast of Morristown, the Morris county seat, and 17 miles (27 km) northwest of Newark. Interstate 287 passes 3 miles (5 km) west of the community, and Interstate 80 passes 2 miles (3 km) to the south.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Lake Hiawatha CDP has a total area of 1.11 square miles (2.87 km2), of which 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2), or 0.81%, are water.[1] The Rockaway River forms the eastern edge of the community and flows southeast to join the Passaic River, part of the watershed of Newark Bay.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 10,194 | — | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 10,194. The Census' American Community Survey estimated 4,158 households, and 2,540 families in Lake Hiawatha as of the period 2018-2022. During that time period, the racial makeup of the community was an estimated 51.6% white, 3.8% black or African-American, 0.3% Native American, 32.9% Asian, 0% Pacific Islander, and 9.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 9.9% of the population.[18]

Among the Asian population, largest ancestry groups were Indian, 2,422 (24%), followed by Chinese, 266 (2.6%), and Filipinos, 255 (2.5%). [19] Among Hispanics and Latinos, the largest ancestry groups were Colombian, 193 (1.9%), followed by Chilean, 171 (1.7%), and Dominican, 147 (1.5%).[20]

Notable people

[edit]People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Lake Hiawatha include:

- Hector A. Cafferata Jr. (1929–2016), United States Marine awarded the Medal of Honor for his service at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War[21]

- Bobby Darin (1936–1973), singer, who purchased a house in Lake Hiawatha with income from his 1959 rock and roll single "Dream Lover"[22]

- Phebe Ann Jacobs (1785–1850), devout Congregationalist and free woman born on the Beverwyck plantation in Lake Hiawatha.[12] Her biography inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 abolitionist novel Uncle Tom's Cabin.[13]

- Al Krevis (born 1952), former American football player who played at offensive tackle in the NFL for the New York Jets and the Cincinnati Bengals[23]

- Garrett Reisman (born 1968), physics professor, former NASA astronaut aboard the International Space Station, author, and former SpaceX executive. He spent a combined 107 days in space and performed three space walks.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "2024 U.S. Gazetteer Files: New Jersey". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ a b QuickFacts Lake Hiawatha CDP, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 21, 2023.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed June 9, 2023.

- ^ "Lake Hiawatha". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ State of New Jersey Census Designated Places - BVP20 - Data as of January 1, 2020, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ Locality Search, State of New Jersey. Accessed June 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "Parsippany Mayor Announces $4 Million in Investments for North Beverwyck Road and Lake Hiawatha". Insider NJ. December 1, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Parsippany Not Quite the Same as Gen. Washington or Gov. Livingston Would Have Remembered It". Parsippany, NJ Patch. April 13, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "NJDEP-News Release 04/32 - DEP's Historic Preservation Office Names the Beverwyck Site to the New Jersey Register of Historic Places". www.nj.gov. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c National Park Service. "National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet". United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021.

- ^ "The New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, No. 855". March 21, 1768.

- ^ a b c d e "Mrs. T. C. Upham Narrative of Phebe Ann Jacobs". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Summary of Narrative of Phebe Ann Jacobs". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Cahill, Frank L. (May 18, 2015). "Lake Hiawatha Fire Department Holds Annual Boot Drive | Parsippany Focus". Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Blackface: the Sad History of Minstrel Shows". AMERICAN HERITAGE. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ A bronze plaque within the library reads "LAKE HIAWATHA PUBLIC LIBRARY - Donated by Benjamin J. Kline - 1948 - "

- ^ Fagan, David M. Zimmer, Dave Sheingold, Svetlana Shkolnikova and Matt. "Sorry, your New Jersey hometown may not be a town at all". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "QuickFacts: Lake Hiawatha CDP, New Jersey". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ "Census Reporter: Making Census Data Easy to Use". censusreporter.org. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "Grid View: Table B03001 - Census Reporter". censusreporter.org. Archived from the original on December 18, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "Ex-Morris vet's name to grace Florida school". Daily Record. February 25, 2005. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

Cafferata was born in New York City, but moved to Morris County with his family when he was 9 years old and lived in Lake Hiawatha and Montville. He graduated from Boonton High School in 1949, and was one of the first inductees to the school's Hall of Fame in 1996.

- ^ "The Small World Of Mr. Big", BobbyDarin.net. Accessed February 10, 2022. "Bobby Darin's been called the most conceited guy in show business. Is he really? C'mon along with us to a humble little cottage on Lake Hiawatha, New Jersey, and be the first to meet the real BD!"

- ^ Castellano, Dan. "Al Krevis Awaits NFL Call", Daily Record, January 5, 1975. Accessed March 28, 2023, via Newspapers.com. "And it was only six years ago that opposing high school coaches were waiting to meet Morris Catholic and its star two-way lineman who most thought was overrated and getting by on size alone.... And the highly articulate 22-year-old from Lake Hiawatha is certainly aware of his prowess."

- ^ "Campus Life: Penn; 'Tigers' Attacked, And Princeton Gets an Apology", The New York Times, November 12, 1989. Accessed February 10, 2022. "Penn officials found the heads with the help of the university's Interfraternity Council president, Garrett Reisman, a senior in Penn's management and technology program from Lake Hiawatha, N.J."