The Roulin Family

| Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin (1841–1903) F432 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | early August, 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 81.2 cm × 65.3 cm (32.0 in × 25.7 in) |

| Location | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

The Roulin Family is a group of portrait paintings Vincent van Gogh executed in Arles in 1888 and 1889 of Joseph, his wife Augustine and their three children: Armand, Camille and Marcelle. This series is unique in many ways. Although Van Gogh loved to paint portraits, it was difficult for financial and other reasons for him to find models. So, finding an entire family that agreed to sit for paintings — in fact, for several sittings each — was a bounty.

Joseph Roulin became a particularly good, loyal and supporting friend to Van Gogh during his stay in Arles. To represent a man he truly admired was important to him. The family, with children ranging in age from four months to seventeen years, also gave him the opportunity to produce works of individuals in several different stages of life.

Rather than making photographic-like works, Van Gogh used his imagination, colours and themes artistically and creatively to evoke desired emotions from the audience.

Background

[edit]This series was made during one of Van Gogh's most prolific periods. The work allowed him to pull artistic learnings over the past several years towards the goal of expressing something meaningful as an artist.

Van Gogh moves to Arles

[edit]Van Gogh moved to Arles in southern France in 1888, where he produced some of his best work. His paintings represented different aspects of ordinary life, such as portraits of members of the Roulin family. The sunflower paintings, some of the most recognizable of Van Gogh's paintings, were created in this time. He worked continuously to keep up with his ideas for paintings. This is likely one of Van Gogh's happier periods of life. He is confident, clear-minded and seemingly content.[1]

In a letter to his brother, Theo, he wrote, "Painting as it is now, promises to become more subtle – more like music and less like sculpture – and above all, it promises colour." As a means of explanation, Vincent explains that being like music means being comforting.[1]

Portrait

[edit]Van Gogh, known for his landscapes, seemed to find painting portraits his greatest ambition.[2] He said of portrait studies, "the only thing in painting that excites me to the depths of my soul, and which makes me feel the infinite more than anything else."[3] Van Gogh wrote further of the meaning he wished to evoke: "in a picture I want to say something comforting as music is comforting. I want to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolize, and which we seek to communicate by the actual radiance and vibration of our colouring."[4]

As much as Van Gogh liked to paint portraits of people, there were few opportunities for him to pay or arrange for models for his work. He found a bounty in the work of the Roulin family, for which he made several images of each person. In exchange, Van Gogh gave the Roulins one painting for each family member.[5]

As the Roulin family was similar in size to Van Gogh's own, in his psychological approach Lubin suggested that Van Gogh may have adopted them as a substitute.[6]

Van Gogh painted the family of postman Joseph Roulin in the winter of 1888, every member more than once.[7] The family included Joseph Roulin, the postman; his wife, Augustine; and their three children. Van Gogh described the family as "really French, even if they look like Russians."[8] Over the course of just a few weeks, he painted Augustine and the children several times. The reason for multiple works was partly so that the Roulins could have a painting of each family member, so that with these pictures and others, their bedroom became a virtual "museum of modern art." The family's consent to modeling for van Gogh also gave him the opportunity to create more portraits, which was both meaningful and inspirational to van Gogh.[9]

Van Gogh used color for dramatic effect. Each family member's clothes are done in bold primary colours and van Gogh used contrasting colours in the background to intensify the impact of the work.[4]

Joseph

[edit]Joseph Roulin was born on 4 April 1841 in Lambesc. His wife, née Augustine-Alix Pellicot, was also from Lambesc; they married 31 August 1868.[10] Joseph, 47 years of age at the time of these paintings, was ten years his wife's senior. Theirs was a working class household.[11] Joseph worked at the railroad station as an entreposeur des postes. Van Gogh and Joseph Roulin met and became good friends and drinking companions. Van Gogh compared Roulin to Socrates on many occasions; while Roulin was not the most attractive man, van Gogh found him to be "such a good soul and so wise and so full of feeling and so trustful." Strictly by appearance, Roulin reminded van Gogh of Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky – the same broad forehead, broad nose, and shape of the beard.[11] Roulin saw van Gogh through the good and the most difficult times, corresponding with his brother, Theo following his rift with Gauguin and being at his side during and following the hospital stay in Arles.[12]

In the very first days of December 1888 Vincent told his brother Theo:

I have made portraits of a whole family, that of the postman whose head I had done previously – the man, his wife, the baby, the young boy, and the son of sixteen, all of them real characters and very French, though they look like Russians. Size 15 canvases. You know how I feel about this, how I feel in my element, and that it consoles me up to a certain point for not being a doctor. I hope to get on with this and to be able to get more careful posing, paid for by portraits. And if I manage to do this whole family better still, at least I shall have done something to my liking and something individual. Just now I am completely swamped with studies, studies, studies, and this will go on for quite a while – it makes such a mess that it breaks my heart, and yet it will provide me with some property when I'm forty.[13]

The size given (Toile de 15, c. 65 x 54 cm), the complete set can be identified:

Augustine

[edit]Augustine Roulin (née Augustine-Alix Pellicot) was born on 9 October 1851 in Lambesc and died on 5 April 1930.[10]

After her husband had posed for several works with van Gogh, Augustine sat for Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin in the Yellow House the two men shared. During the sitting, she kept her gaze on Gauguin, possibly for reassurance because, according to her daughter, she was not comfortable in the presence of van Gogh. She sat in the corner of the room for the evening sitting. The resulting paintings were quite different, as was typical of the sessions where the artists shared the same model. Gauguin's portrait included as background a picture he recently completed entitled Blue Trees. He painted Augustine in straightforward, literal way.[14]

In comparison, Van Gogh's work appeared more quickly executed and more thickly painted than that of Gauguin's painting. Van Gogh admired the work of Dutch master Frans Hals whose portraits display lively brushwork and the direct, spontaneous style of alla prima, or wet-on-wet . The yellow brushstrokes on the side of her head depict the gaslight. Instead of depicting the evening mood, he painted pots of sprouting bulbs. Van Gogh made a connection to her earthy nature by the depiction of germinating bulbs, essentially declaring her a "human tuber." Days after working on this painting Van Gogh began painting the remaining Roulin family members, including the four-month-old baby, Marcelle.[14]

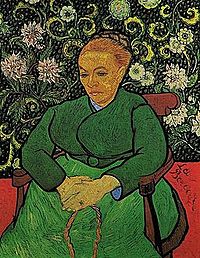

In addition to the mother-daughter works where Marcelle is visible, Van Gogh also created several La Berceuse [la bɛʁsøz] works where Augustine rocked her unseen cradle by a string.[15] Van Gogh labeled the group of work La Berceuse meaning "our lullaby or the woman rocking the cradle." The colour and setting were intended to set the scene of a lullaby, meant to give comfort to "lonely souls." Van Gogh imagined the painting in several types of settings, such as on an Icelandic fishing boat cabin walls—or the center piece to two Sunflower paintings.[10]

There is a fifth version of the painting at the Art Institute of Chicago.[16]

Armand

[edit]Armand Roulin, the eldest son, was born on 5 May 1871 in Lambesc, and died on 14 November 1945. He was 17 years of age when portrayed by Van Gogh.[17] Van Gogh's works depict a serious young man who at the time the paintings were made had left his parents' home, working as a blacksmith's apprentice.[18] The Museum Folkwang work depicts Armand in what are likely his best clothes: an elegant fedora, vivid yellow coat, black waistcoat and tie.[18][19] Armand's manner seems a bit sad, or perhaps bored by sitting.[19] His figure fills the picture plane giving the impression that he is a confident, masculine young man.[18]

The second work, with his body slightly turned aside and his eyes looking down, appears to be a sad young man.[18] Even the angle of the hat seems to indicate sadness. Both museum paintings were made on large canvas, 65 x 54 cm.[19]

Loving Vincent,[20] a movie based on the life of Vincent van Gogh, features Armand Roulin as the main character. In it, Roulin's asked by his father, Joseph, to deliver a letter to Vincent's brother, Theo van Gogh. The critically acclaimed film employed oil painters trained to paint like van Gogh. Their paintings were used in each frame of the movie, using stills of van Gogh's real paintings and basing Armand Roulin's character design on another of van Gogh's paintings. Many of van Gogh's portraits, like Portrait of Armand Roulin (1888), provided designs for the movie's characters.[21]

Camille

[edit]Camille Roulin, the middle child, was born in Lambesc in southern France, on 10 July 1877, and died on 4 June 1922.[10] When his portrait was painted, Camille was eleven years of age. The Van Gogh Museum painting[8] shows Camille's head and shoulders. Yellow brush strokes behind him are evocative of the sun.[19]

A very similar painting resides at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (F537).[22]

In The Schoolboy with Uniform Cap Camille seems to be staring off in space. His arm is over the back of a chair, mouth gaped open, possibly lost in thought. This was the larger of the two works made of Camille.[19]

Marcelle

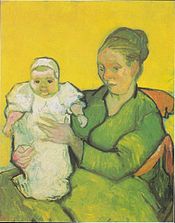

[edit]Marcelle Roulin, the youngest child (31 July 1888 – 22 February 1980) was four months old, when Van Gogh made her portraits.[10] She was painted three times by herself and twice on her mother’s lap.[7] The three works show the same head and shoulders image of Marcelle with her chubby cheeks and arms against a green background.[23]

When Johanna van Gogh, pregnant at the time, saw the painting, she wrote: "I like to imagine that ours will be just as strong, just as beautiful – and that his uncle will one day paint his portrait!"[7] A version titled Roulin's Baby resides at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[24]

In Philadelphia Museum of Art's Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle Augustine holds baby Marcelle who was born in July, 1888. The mother, relaxed and her face in a shadow, is passive. We can see by the size of Augustine's sloping shoulders, arm, and hands that she worked hard to take care of her family. For instance, there were no modern conveniences like washing machines. In a traditional pose of mothers and new babies, Augustine is holding her baby upright, supporting the baby's back by her right arm and steadying the baby's midsection with her left hand. Marcelle, whose face is directed outward, is more active and engages the audience. Van Gogh used heavy outlines in blue around the images of mother and baby.[4]

To symbolize the closeness of mother and baby, he used adjacent colours of the colour wheel, green, blue and yellow in this work. The vibrant yellow background creates a warm glow around mother and baby, like a very large halo. Of his use of colour, Van Gogh wrote: "instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use colour...to express myself more forcibly." The work contains varying brushstrokes, some straight, some turbulent – which allow us to see the movement of energy "like water in a rushing stream." Émile Bernard, Van Gogh's friend, was the initial owner of this painting in its provenance.[4]

See also

[edit]- List of works by Vincent van Gogh

- Portraits by Vincent van Gogh

- Paintings of Children (Van Gogh series)

Resources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Morton, M; Schmunk, P (2000). The Arts Entwined: Music and Painting in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 177–178. ISBN 0-8153-3156-8.

- ^ Cleveland Museum of Art (2007). Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-940717-89-3.

- ^ "La Mousmé". Postimpressionism. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2011Additional information about the painting is found in the audio clip.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c d "Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle". Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011Additional information in "Teacher Resources" and audio clip.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ Lubin, Stranger on the earth: A psychological biography of Vincent van Gogh, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1972. ISBN 0-03-091352-7, page 162.

- ^ a b c "Portrait of Marcelle Roulin, 1888". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Portrait of Camille Roulin, 1888". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ a b c d e Jiminez, J; Banham, J (2001). Dictionary of Artists' Models. Chicago: Dearborn Publishers. p. 469. ISBN 1-57958-233-8.

- ^ a b Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. pp. 200, 203–206. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ Silverman, D (2000). Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 318. ISBN 0-374-28243-9.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written c. 4 December 1888 in Arles". van Gogh, J (trans.). WebExhibits. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. pp. 196–190. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. Da Capo Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.

- ^ "Madame Roulin Rocking the Cradle (La Berceuse), 1889". Collection. The Art Institute of Chicago. 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Letters of Joseph Roulin to Vincent van Gogh, 22 May and 24 October 1889; see Van Crimpen, Han & Berends-Alberts, Monique: De brieven van Vincent van Gogh, SDU Uitgeverij, The Hague 1990, pp. 1878–79 (No. 779); 1957–58 (Nr. 816) – both letters, written in French, are hitherto only published in Dutch translation.

- ^ a b c d Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. University of California Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 9780520088498.

- ^ a b c d e Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ "Review: 'Loving Vincent' Paints van Gogh in His Own Images". The New York Times. 2017-09-21. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ^ internetowe, Odee – odee.pl / Strony. "Home". lovingvincent.com. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ^ "Portrait of Camille Roulin". Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ "Roulin's Baby". The Collection. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Pierre Michon, Vie de Joseph Roulin(fr)

- Van Gogh, paintings and drawings: a special loan exhibition, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on these paintings (see index)

- Portrait of Joseph Roulin 1888 (Van Gogh) - Video at Check123 - Video Encyclopedia