LGBTQ rights in Azerbaijan

LGBTQ rights in Azerbaijan | |

|---|---|

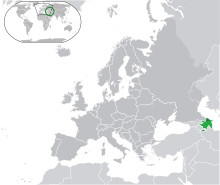

Location of Azerbaijan (green) | |

| Status | Legal since 2000[1] |

| Gender identity | No |

| Military | No |

| Discrimination protections | No |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No recognition of same-sex relationships |

| Adoption | No |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Azerbaijan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Azerbaijan since 1 September 2000.[2] Nonetheless, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity are not banned in the country and same-sex marriage is not recognized.

Homosexuality remains a taboo subject in the Azerbaijani society, as each year since 2015, ILGA-Europe has ranked Azerbaijan as the worst state (49 out of 49) in Europe for LGBTQIA+ rights protection, citing "a near total absence of legal protection" for LGBTQIA+ individuals.[3] In September 2017, reports emerged that at least 100 members of Baku's LGBTQIA+ community were arrested, ostensibly as part of a crackdown on prostitution. Activists reported that these detainees were subject to beatings, interrogation, forced medical examinations and blackmail.[4][5][6]

LGBTQIA+ people face high rates of violence, harassment and discrimination.[7]

History and legality of same-sex sexual activity

[edit]After declaring independence from the Russian Empire in 1918, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic did not have laws against homosexuality. When Azerbaijan became a part of the Soviet Union in 1920, it was subject to rarely enforced Soviet laws criminalizing the practice of sex between men. Despite Vladimir Lenin having decriminalized homosexuality in Soviet Russia (inexplicitly; the Tsarist legal system was abolished, thus decriminalising sodomy), sexual intercourse between men (incorrectly termed pederasty in the laws, rather than the technically accurate term sodomy) became a criminal offence in 1923 in the Azerbaijan SSR,[8] punishable by up to five years in prison for consenting adults, or up to eight years if it involved force or threat.[9][10]

Azerbaijan regained its independence in 1991, and in 2000 repealed the Soviet-era anti-sodomy law.[11] A special edition of Azerbaijan, the official newspaper of the National Assembly, published on 28 May 2000, reported that the National Assembly had approved a new criminal code, and that President Heydar Aliyev had signed a decree making it law beginning on 1 September 2000. Repeal of Article 121 was a requirement for Azerbaijan to join the Council of Europe,[12] which Azerbaijan did on 25 January 2001.[13]

The age of consent is now equal for both heterosexual and homosexual sex, at 16 years of age.[2]

Azerbaijan's anti-LGBTQIA+ discrimination has stirred controversy in relation to international events hosted by Azerbaijan, with critics arguing that Azerbaijan should not be allowed to host international events due to its discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people.[14]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

[edit]Same-sex couples are not legally recognised.[14] Same-sex marriage and civil unions are not recognized or performed.[15]

Adoption and family planning

[edit]Same-sex couples are not allowed to adopt children in Azerbaijan.[14]

Military service

[edit]Azerbaijan implements mandatory military conscription for all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 35 to enlist in the military. There is no specific law that prohibits lesbians, gays and bisexuals from serving in the Azerbaijani military, however they could be unfit to serve under the Articles 18/b and 17/b of the Regulation on Military Medical Examinations. Article 18, paragraph b of the Regulation on Military Medical Examinations, states a person is considered unfit or partially unfit for military service on the basis of personality disorders. In addition to Article 18/b, LGBTQIA+ enlistees are also categorized under Article 17/b, which indicates reactive psychoses and neurotic disorders.[16]

Gender identity and expression

[edit]Azerbaijan possesses no legislation enabling transgender people to legally change their gender on official documents. However, transgender people are allowed to change their name so that it matches their gender identity.[15]

Blood donation

[edit]It is unknown if men who have sex with men are permitted to donate blood. By law, no groups are excluded from blood donation apart from HIV/AIDS infected persons.[15]

Living conditions

[edit]

Azerbaijan is largely a secular country with one of the least practicing majority-Muslim populations.[17] The reason behind homophobia is mostly due to the lack of knowledge about it, as well as due to the "old traditions".[18] Families of homosexuals often cannot come to terms with the latter's sexuality, especially in rural areas. Coming out often results in violence or ostracism by the family patriarchs or forced heterosexual marriage.[19][20]

There were rumours of an LGBTQIA+ parade being organized in time for the Eurovision Song Contest 2012, which was hosted by Azerbaijan. This caused disagreement in society due to homophobic views, but it did gain support from Azerbaijani human rights activists.[21] The contest's presence in Azerbaijan also caused diplomatic tensions with neighbouring Iran. Iranian clerics Ayatollah Mohammad Mojtahed Shabestari and Ayatollah Ja'far Sobhani condemned Azerbaijan for "anti-Islamic behaviour", claiming that Azerbaijan was going to host a gay parade.[22] This led to protests in front of the Iranian embassy in Baku, where protesters carried slogans mocking the Iranian leaders. Ali Hasanov, head of the public and political issues department in the Azerbaijani President's administration, said that gay parade claims were untrue, and warned Iran not to meddle in Azerbaijan's internal affairs.[23] In response, Iran recalled its ambassador from Baku,[24] while Azerbaijan demanded a formal apology from Iran for its statements in connection with Baku's hosting of the Eurovision Song Contest,[25] and later also recalled its ambassador from Tehran.[26]

LGBTQIA+ people have gained more visibility in recent years, through various interviews, social media posts and films. For Pride Month in 2019, several Azerbaijani celebrities shared social media posts supporting LGBTQIA+ rights, including singer Röya, stylist Anar Aghakishiyev and 2011 Eurovision winner Eldar Gasimov.[27]

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Azerbaijan since 1 September 2000.[2] Nonetheless, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity is not banned in the country and same-sex marriage is not recognized.

Society

[edit]

As in most other post-Soviet era countries, Azerbaijan remains a place where homosexuality is an issue surrounded by confusion. There is hardly any objective or correct information on the psychological, sociological and legal aspects of homosexuality in Azerbaijan, with the result that the majority of the society simply does not know what homosexuality is.[5][18][28]

"Coming out" as a gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender person is therefore rare, and individual LGBT people are afraid of the consequences. Thus many lead double lives, with some feeling deeply ashamed about being gay.[20] Those who are financially independent and living in Baku are able to lead a safe life as an LGBTQIA+ person, as long as they "practice" their homosexuality in their private sphere. There is a small LGBT movement, with three organizations advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights and protection.[29]

Although homosexual acts between consenting male adults are officially decriminalized, reports about police abuses against gays, mainly male prostitutes, have persisted. While complaining of the violence against them, the victims preferred to remain anonymous fearing retaliation on the part of the police.[5] In 2019, in A v. Azerbaijan, the European Court of Human Rights called out the state for its 2017 raids in which over 80 LGBT people were detained, many tortured and abused by police.[30]

In April 2019, Elina Hajiyeva, a 14-year-old girl from Baku, attempted suicide once more due to homophobic bullying at her school. Although her mother had reported the bullying to the principal, Sevinj Abbasova, neither she nor other teachers took any action against it. After the attempted suicide, the principal kept Hajiyeva in her office for an hour during which she attempted to have the half-conscious Hajiyeva admit to suicidal tendencies and place the blame on family difficulties rather than on bullying issues at the school. She did not call an ambulance or allow others to do so.[31] Hajiyeva died in hospital two days later. The school director, deputy director and school psychologist were dismissed from office. Only the principal was prosecuted on account of negligence resulting in death, and leaving someone in danger. On 24 October 2019, the principal was sentenced by the Sabail District Court of Baku to 2 years and 2.5 months of restriction of liberty, which means movement surveillance,[32] only requiring her to be home at 9:00 PM.[33] She was also ordered to pay 18,500 AZN ($10,882) of monetary compensation to the parents.[34]

The case sparked a nationwide social media campaign against bullying. 2011 Eurovision winner Nigar Jamal posted a video on Instagram addressed to President Ilham Aliyev asking government officials to take action. The Ministry of Education launched an action plan against bullying on 13 May, envisaging a number of tasks to ensure a "healthy environment in general education institutions", to improve school and family relations and to protect students from abuse. A hotline was also established.[35]

In May 2019, Azerbaijan Airlines fired three employees for releasing personal information of a transgender passenger on social media, including a picture of her passport.[36] In June 2019, five transgender women were physically assaulted by a group of 15 men in Mardakan. Four of the attackers were arrested.[37] In September 2019, a young gay man was beaten, raped and expelled from his village of Yolçubəyli because of his sexuality. He reported the violence to police. Photos of his rape surfaced online.[38]

Media

[edit]The first news website for LGBTQIA+ people in Azerbaijan was launched by Ruslan Balukhin on 25 May 2011: gay.az.

The Azerbaijani Constitution guarantees freedom of expression for everyone by all forms of expressions.[39] The Azerbaijan Press Council was founded in 2003. The council deals with complaints according to the Press Code of Conduct. It is unknown if the council has assessed complaints of harassment made by state-controlled media using homosexuality as a tool to harass and discredit critics of the government.[15]

The media in Azerbaijan has been criticized for spreading fear and hate towards queer people, with the use of discriminatory language and the portrayal of queer individuals in a negative light. Queer people face discrimination in various aspects of life, and the media often becomes a tool for propaganda and disinformation, with politicians and officials using it to influence the public's perception of queer individuals. Vahid Aliyev, a co-founder of the Minority Azerbaijan news webpage, has criticised the media for their unprofessional manners and their impact on shaping public opinion.[40]

Azerbaijan's human rights NGOs have been successful in raising awareness of the lives of Azeri LGBTQIA+ people.[41]

The first LGBTQIA+ online magazine Minority Magazine was founded by Samad Ismayilov in December 2015. The magazine covers education, entertainment and current issues about LGBT people. The magazine started functioning as an NGO from August 2017.[42]

Film

[edit]Samad Ismayilov, an LGBTQIA+ activist and the founder of Minority Magazine, made a documentary movie about a trans man from Azerbaijan named Sebastian. The film focuses on Sebastian's challenges, fears and dreams about the future. It was filmed in Ohio in the United States. The film made its debut in Baku on 25 November 2017, with the support of the Dutch embassy. About 80 people came to watch the movie and participate at LGBTQIA+ discussions after the film.[43]

Deniz Miray, who is trans rights activist and film critic, shot her "Bədənimə Günəş" in 2022 by talking about the challenges of LGBTQI+ individuals in Azerbaijan.[44]

Literature

[edit]In 2009, Ali Akbar wrote a scandalous book titled Artush and Zaur, which focused on homosexual love between an Armenian and Azerbaijani. According to Akbar, being an Armenian and being gay are major taboos in Azeri society.[45]

In 2014, Azerbaijani writer Orkhan Bahadirsoy published a novel about the love of two young men, It is a sin to love you.[46]

Suicide of Isa Shahmarli

[edit]In January 2014, Isa Shahmarli, the openly gay founder of AZAD LGBT, died of suicide by hanging himself with a rainbow flag. At the time of his death, Shahmarli was unemployed, in debt, and estranged from his family who considered him "ill".[47] Shahmarli left a note on Facebook blaming society for his death. He was discovered soon afterward by friends.[48]

Shahmarli's suicide sparked an increase in LGBTQIA+ activism in Azerbaijan. The day of his death was marked as LGBTQIA+ Pride Day and was honored in 2015 with the release of several videos.[49]

LGBTQI+ organizations

[edit]As of 2015, there are five known LGBT organizations in Azerbaijan:

- Gender and Development (Azerbaijani: Gender və Tərəqqi İctimai Birliyi), created in 2007 and carries out local projects in collaboration with the Ministry of Health.[19][28]

- Nafas LGBTI Azerbaijan Alliance (Azerbaijani: Nəfəs LGBTİ Azərbaycan Alyansı), established in 2012. It has implemented several projects, including part of an international survey and regularly holds talks with the EU Delegation to Azerbaijan and other European embassies regarding the difficulties of LGBT people and their situation in Azerbaijan.[50]

- AZAD LGBT, established in 2012 by Isa Shahmarli. AZAD concentrates on education and better media representation in Azerbaijan. In its first year, it ran several projects including organizing LGBT movie nights in the capital of Baku. These movie nights were attended by a local psychologist who participated in Q&As after the films.

In 2014, after Isa Shahmarli committed suicide, AZAD organized a series of photo and video projects.[49] In 2015, AZAD launched a website providing free online LGBT education tools.[51] - Q-Collective

- Gender Resource Center([1])(Azerbaijani: Gender Resurs Mərkəzi), established in 2020 is a queer-feminist platform.The centre was established in Azerbaijan in response to the problem of lack of safe space and resources for people of different genders and sexual orientations.

Other online campaigns or magazines also exist.

- Gay.az, the first information portal for LGBT people in Azerbaijan

- Love Is Love, an online photo campaign designed to provide support to the LGBT community in Azerbaijan.[52]

- Reng, in remembrance of Isa's birthday, including illustrated versions of several of Isa's writings

- Minority Magazine, which covers education, entertainment and current issues about LGBT people[42]

Human rights reports

[edit]2017 United States Department of State report

[edit]In 2017, the United States Department of State reported the following, concerning the status of LGBT rights in Azerbaijan:

- "The most significant human rights issues included unlawful or arbitrary killing; torture; harsh and sometimes life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest; lack of judicial independence; political prisoners; criminalization of libel; physical attacks on journalists, arbitrary interference with privacy; interference in the freedoms of expression, assembly, and association through intimidation, incarceration on questionable charges, and harsh physical abuse of selected activists, journalists, and secular and religious opposition figures, and blocking of websites; restrictions on freedom of movement for a growing number of journalists and activists; severe restrictions on political participation; and systemic government corruption; and police detention and torture, of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) individuals; and worst forms of child labor, which the government made minimal efforts to eliminate."[53]

- Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

"For example, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) individuals detained in September stated police threatened them with rape, and in some cases raped them with truncheons. Most did not publicize such threats."[53] - Acts of Violence, Discrimination, and Other Abuses Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

"Antidiscrimination laws exist but do not specifically cover lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) individuals.

In October media and human rights lawyers reported that since mid-September police had arrested and tortured 83 men presumed to be gay or bisexual as well as transgender women. Once in custody, police beat the detainees and subjected them to electric shocks to obtain bribes and information about other gay men (see section 1.c.). By 3 October, many of the detainees had been released, many after being sentenced to 20-45 days in jail, fined up to 200 manat ($117), or both. On 2 October, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Office of the Prosecutor General issued a joint statement that denied the arrests were based on gender identity or sexual orientation.

A local NGO reported there were numerous incidents of police brutality against individuals based on sexual orientation and noted that authorities did not investigate or punish those responsible. There were also reports of family-based violence against LGBTI individuals, hate speech against LGBTI persons, and hostile Facebook postings on personal online accounts. Activists reported that LGBTI individuals were regularly fired by employers if their sexual orientation/gender identity became known. One individual reported the military did not allow LGBTI individuals to serve and granted them deferment from conscription on the grounds of mental illness.

LGBTI individuals generally refused to file formal complaints of discrimination or mistreatment with law enforcement bodies due to fear of social stigma or retaliation. Activists reported police indifference to investigating crimes committed against members of the LGBTI community."[53] - Discrimination with Respect to Employment and Occupation

"Discrimination in employment and occupation also occurred with respect to sexual orientation. LGBTI individuals reported employers found other reasons to dismiss them because they could not legally dismiss someone because of their sexual orientation."[53]

Summary table

[edit]| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (16) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment only | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in education | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Hate crime laws include sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Single LGBT people allowed to adopt | |

| Conversion therapy banned | |

| Lesbians, gays and bisexuals allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood | |

| Homosexuality declassified as an illness |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ State-sponsored Homophobia A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults Archived 27 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "LGBT Rights in Azerbaijan | Equaldex". equaldex.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Rainbow Europe - Azerbaijan". ILGA. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Mass Arrests and Abuse of LGBT People in Azerbaijan". 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Walker, Shaun (28 September 2017). "Outcry as Azerbaijan police launch crackdown on LGBT community". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "Azerbaijan: Anti-Gay Crackdown". Human Rights Watch. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "MP'S CALLS FOR HATE WILL RESULT IN AN INCREASE OF HATE CRIMES IN AZERBAIJAN". Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Healey, Dan. "Masculine purity and 'Gentlemen's Mischief': Sexual Exchange and Prostitution between Russian Men, 1861–1941". Slavic Review. Vol. 60, No. 2 (Summer, 2001), p. 258.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Azerbaijan: Information on the Treatment of Homosexuals". Unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Russian S.F.S.R. (1966). Harold Joseph Berman (ed.). Soviet criminal law and procedure: the RSFSR codes (University of California original). Harvard University Press. p. 196. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Spartacus International Gay Guide, p. 1216. Bruno Gmunder Verlag, 2007.

- ^ "Council of Europe". Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Euro 2020: Uefa bans rainbow ads at two quarter-finals". BBC News. 2 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Ismayilzade, Asli (26 November 2021). "'Unfit for military service': How Azerbaijan stigmatizes LGBTQ+ military personnel". GlobalVoices. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ GALLUP WorldView Archived 6 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine - data accessed on 17 January 2009

- ^ a b "ILGA-Europe". Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b Western Media on Eurovision Archived 13 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Radio Liberty. 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Between Appearance and Reality in Baku: LGBT Rights in Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

The gay artist Babi Badalov describes to the BBC his family's reaction when they found out about his homosexuality. For years he had attempted to live according to traditional norms. He even got married, but because he could no longer endure this lifestyle, he applied for asylum in Great Britain. His claim was denied, however, as homosexuality is not a criminal offence in Azerbaijan. A campaign supporting him in Great Britain became known in his hometown in southern Azerbaijan near the Iranian border. His family considered this to be a dishonor. His brother swore that he would kill him and then himself, reported Badalov to the BBC. His sister encouraged him to leave Azerbaijan and never return. Badalov found asylum in France shortly thereafter. (see Eurovision 2012: Azerbaijan's gays not welcome at home by Dina Newman)

- ^ "News.Az - Gay parade in Baku: to be or not to be?". Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Antidze, Margarita (22 May 2012). "Iran's "gay" Eurovision jibes strain Azerbaijan ties". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Lomsadze, Girgoi (21 May 2012). "Azerbaijan: Pop Music vs. Islam". EurasiaNet.org. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Iran recalls envoy to Azerbaijan ahead of Eurovision". AFP. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Demands Apology From Iran Over Eurovision". Voice of America. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Recalls Ambassador To Iran". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Azerbaijani celebrities support Pride Month". minorityaze.org. June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ a b "DISCRIMINATION AND VIOLENCE AGAINST LESBIANS, BISEXUAL WOMEN AND TRANSGENDER PEOPLE IN AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Dennis van der Veur, Forced Out;LGBT people in Azerbaijan, report for ILGA, 2007

- ^ "A. Azerbaijan and 24 other applications". hudoc.echr.coe.int. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Elina Hajiyeva's Mother Calls on Court to Sentence Sevinj Abbasova to Heavy Punishment". Turan Information Agency. 18 October 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Medzhid, Faik (25 October 2019). "Family of schoolgirl who perished in Baku find sentence to teacher too soft". Caucasian Knot. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Geybullayeva, Arzu (1 January 2020). "Azerbaijan - 2019, year of make-up". Osservatorio balcani e caucauso transeuropa. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Baku school principal convicted in death of student – but isn't going to prison". Jam News. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "'Talk to me' - Azerbaijani Ministry of Education Launches Campaign Against Bullying". Jam News. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "An official statement from AZAL regarding the dissemination of a transgender individual document". minorityaze.org. 27 May 2019. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Attack on transgender people in Mardakan". minorityaze.org. 1 July 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Молодого гея из Сабирабада изнасиловали, а после изгнали из села". baku.ws (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Azerbaijan's media — spreading fear and hate of queer people". OC Media. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "LGBT activism in Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Azerbaijan's first LGBT magazine". Meydan.TV. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "SEBASTIAN | Samad Ismayilov". samadismailzadeh. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "- YouTube". YouTube.

- ^ "Armenian Gays Face Long Walk to Freedom". Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

- ^ "Gənc yazardan homoseksuallara dəstək". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Isa Shakhmarli, Azeri Gay Rights Activist, Allegedly Commits Suicide with a Rainbow Flag". The Huffington Post. 23 January 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "LGBT Leader Dies from Apparent Suicide, Hanging Himself with Rainbow Flag". The New Civil Rights Movement. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Declaration of Nefes LGBT Azerbaijan – 22nd January date as 'LGBT Pride Day in Azerbaijan'". IGLHRC: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Nəfəs LGBT Azərbaycan Aliyansı". Nəfəs LGBT Azərbaycan. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Tool Kit". AZAD. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Free LGBT says Love is Love". Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Azerbaijan 2017 Human Rights Report" (PDF). United States Department of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ NafasLGBTI (15 September 2024). "Yeni Tədris ili - Universitetlərin bərabərlik, müxtəliflik və inklüzivlik üzrə qaydaları". Xoş gördük! (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Minority Azerbaijan - Health Ministry of Azerbaijan About Homosexuality". minorityaze.org. Retrieved 10 January 2024.