LGBT history in Italy

Appearance

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

This article is about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) history in Italy.

BCE

[edit]

- 5th millennium BC - Examples of homosexual eroticism in Upper Paleolithic or Mesolithic European art in Sicily. In Addaura incision is a group of people dancing around two men, both with erections, possibly indicating a homoerotic ritual.[1][2]

- 530 BC – One of the earliest examples of Etruscan art on homosexuality, found in 1892 in the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia. The painting, situated in what has been called the Tomb of the Bulls (Italian: Tomba dei Tori), depicts on the right a bull with a man's face (Acheloos) and an erect phallus that is aggressively approaching two men having sexual intercourse. On the left, another bull is turned around, as though indifferent, in front of men and women having sexual intercourse. The women are consistently depicted in light tones, while the men are brown. Under the frieze is Achilles (on the left) waylaying Troilus. This representation is the only one in archaic Tarquinian parietal painting representing a scene derived from Greek mythology; it used the legend about the bisexuality of Achilles to demonstrate that, among the Greeks, same-sex love was a common and ordinary fact. This shows how, even then, homosexuality could be a worthwhile topic in the conflict between populations. Below is the tree of life, full of leaves, linked by the sash of life with the skeletal tree of death, with the black festoon of death hanging from a branch. The onomastic inscription in the centre of the upper frieze names he who probably was the owner of the tomb: Aranth Suprianas.

- 470 BC – An important example is the "Tomb of the Diver" in Paestum, in particular the painted scene of the Symposium.

600 BC – 1 BC

[edit]- 509 BC – The Roman Republic is founded. Homosexuality, as in Greece, is widespread and legalized throughout the Roman heyday, from the Republic to the Empire (see Homosexuality in ancient Rome).

- 149 BC – The Lex Scantinia, a Roman law, regulates homosexuality for the first time on record. According to the law, homosexuality should be denied between freeborn adult males and for the youth of noble families not to participate in male prostitution. It is also probable that such a law was meant to prevent the possibility of a noble-born man becoming subject to sodomy by a slave.[3]

1st century BC

[edit]- 100 BC – 100 AD – Found in the Terme suburbane of Pompei is the only representation of a lesbian scene surviving from the Roman era, and also a fresco of triple intercourse between men.

- 80 BC – Julius Caesar allegedly has a love affair with king Nicomedes IV of Bithynia.[4]

- 57 BC – 54 BC – Catullus writes the Carmina, including love poems to Giovenzio, boasting of sexual prowess with youth and including violent invective against passive sodomites.

- 42 BC – 39 BC – Virgil writes the Eclogæ vel Bucolica, with many references to homosexual love and relationship.

- 27 BC – The Roman Empire begins with the reign of Augustus. The first recorded same-sex marriages occur during this period.[5]

- 26, 25, and 18 BC – Tibullus writes the Carmina, with references to homosexuality.

Romans, like Greeks, tolerated love and sex among men. Two Roman Emperors publicly married men, some had gay lovers themselves, and homosexual prostitution was taxed. However, like the Greeks, passivity and effeminacy were not tolerated, and an adult male freeborn Roman could lose his citizen status if caught performing fellatio or being penetrated.[6]

AD 1 – 599

[edit]1st century CE

[edit]

- 8 – Female same-sex desire is described as something strange and unnatural in Ovid's Metamorphoses, in the tale of Iphis and Ianthe."So, birds mate, and among all animals, not one female is attacked by lust for a female. I wish I were not one!" says Iphis of her desire for Ianthe.[7]

- 54 – Nero becomes Emperor of Rome. Nero married two men in legal ceremonies, Pythagoras and Sporus.[8]

- 86-93 – The Roman poet Martial satirizes lesbians and his own mystification about lesbianism in his Epigrams. "Only the Sphinx could interpret this riddle right: that where there is no man, there is adultery."[7]

- 98 – Trajan, one of the most beloved of Roman emperors, begins his reign. Trajan was well known for his homosexuality and fondness for young males. This was used to advantage by the king of Edessa, Abgar VII, who, after incurring the anger of Trajan for some misdeed, sent his handsome young son to make his apologies, thereby obtaining pardon.[9]

2nd century

[edit]- 165 – Christian martyr Giustino writes: "We have learned that is an evil thing to show newborns, since we see that almost everyone, not only the girls but boys too, are forced into prostitution".[10]

3rd century

[edit]- 218 – The emperor Elagabalus's reign begins. At different times, Elagabalus marries five women and a man named Zoticus, an athlete from Smyrna, in a lavish public ceremony at Rome;[11] but the Syrian's most stable relationship is with the chariot driver Hierocles, and Cassius Dio says Elagabalus delighted in being called Hierocles' mistress, wife, and queen.[12] The emperor wears makeup and wigs, prefers to be called a lady and not a lord, and offers vast sums to any physician who can provide him with a vagina;[12][13] for this reason, the emperor is seen by some writers as an early transgender figure and one of the first on record as seeking sex reassignment surgery.[12][13][14][15]

- 244–249 – Emperor Philip the Arab tries and fails to outlaw homosexual prostitution.[6]

4th century

[edit]- 342 – The first law against pretended same-sex marriage was promulgated by the Christian emperors Constantius II and Constans.[16]

- 390 – In the year 390, the Christian emperors Valentinian II, Theodosius I and Arcadius declared homosexual sex to be illegal and those who were guilty of it were condemned to be burned alive in front of the public.[17]

5th century

[edit]- 498 – In spite of the laws against gay sex, the Christian emperors continued to collect taxes on male prostitutes until the reign of Anastasius I, who finally abolishes the tax in favor of sampling of the best men.[18]

6th century

[edit]- 529 – The Christian emperor Justinian I (527–565) makes homosexuals a scapegoat for problems such as "famines, earthquakes, and pestilences."[19] The Justinian code is the first time active as well as passive homosexuals are punished; prominent religious leaders are castrated, tortured, dragged through the streets, and executed. This code shapes the status of homosexuals in Europe for the next several hundred years, until the Napoleonic Era.[20]

1000–1599

[edit]- 1051 – Peter Damian writes the treatise Liber Gomorrhianus, in which he argues for stricter punishments for clerics failing their duty against "vices of nature."[21]

- 1140 – The Italian Monk Gratian compiles his work Decretum Gratiani, in which he argues that male homosexual acts are the worst of all the sexual sins because they involve using the male member in an unnatural way.[6]

- 1179 – The Third Lateran Council of Rome issues a decree for the excommunication of male homosexuals.

13th century

[edit]- 1232 – Pope Gregory IX starts the Inquisition in the Italian city-states. Some cities called for banishment and/or amputation as punishments for 1st- and 2nd-offending sodomites and burning for the 3rd or habitual offenders.[citation needed]

- 1250–1300 – Homosexual activity radically passes from being completely legal in the most of Europe to incurring the death penalty in most European states.[22]

- 1265 – Thomas Aquinas argues that sodomy is second only to murder in the ranking of sins.[6]

- 1287 – Niger de Pulis is burned at the stake in Parma (then part of the Holy Roman Empire), becoming the first person in modern-day Italy to be executed for sodomy.[23]

14th century

[edit]

- 1321 – Dante's Inferno places male homosexuals in the Seventh Circle.

- 1345 – Guido da Pisa writes a commentary on Divine Commedia, in which an illustration depicts Dante, Virgil, and homosexuals.

- 1347 – Rolandino Roncaglia is put on trial for homosexuality, an event that caused a sensation in Italy. He confessed he "had not ever had sexual intercourses neither with his wife nor with any other woman because he didn't ever feel any carnal appetite, nor could he ever have an erection of his virile member". After his wife died of plague, Rolandino started to prostitute himself, wearing female dresses because "since he has a female look, voice and movements – although he hasn't the female orifice but has a male member and testicles – many persons considered him to be a woman because of his appearance".[24]

15th century

[edit]- 1476 – Florentine court records of 1476 show that Leonardo da Vinci and three other young men were charged with sodomy, and acquitted.[25] During the 15th century, Florence has a reputation abroad as "the capital of the sodomites" and the majority of men in the city are "at least once during their lifetimes officially incriminated for engaging in homosexual relations", according to historian Michael Rocke.[26]

16th century

[edit]

- 1512 – Renowned Sienese painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi is nicknamed Il Sodoma ('The Sodomite') because of his homosexual activities. Bacci embraces the name and writes verses about it.[27]

- 1532 – Holy Roman Empire makes sodomy punishable by death.[6]

- 1541 – Writer and noblewoman Laudomia Forteguerri publishes a series of love poems dedicated to her friend Margaret of Austria.[28] Maddelena Campiglia is another 16th century female poet who explores the love between women in the 1580s.[29]

- 1500s – Same-sex desire between women is mentioned in several late 16th century romantic comedies of Italian Renaissance theater, usually in the context of one or more characters secretly cross-dressing as the opposite sex. "I am not the first person who has loved a woman", says "the female Cesare" in the play Alessandro. "Histories, ancient and modern, are full of accounts which have reinforced this fire that consumes me".[30]

- 1578 – A community of men who performed same-sex marriages with one another is discovered in San Giovanni in Porta Latina basilica in Rome. Eight men are hanged and their bodies burned as a result. A later episode of same sex marriage involving clergymen is discovered in Naples.[31]

17th century

[edit]- 1620s – Lesbian nun Benedetta Carlini, the abbess of the Convent of the Mother of God in Pescia, shares her cell with Sister Bartolomea. When the two nuns make love, Sister Benedetta experiences mystical visions and angelic possession. The ecclesiastic forces of the Counter-Reformation investigate her mystical experiences and, upon discovering her lesbian sexuality, strip her of her position as abbess and hold her under guard for the remainder of her life.

18th century

[edit]- 1755 – Gay art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann comes to Rome and spends the rest of his life in Italy, where he earns the admiration of his intellectual contemporaries such as Goethe and Herder for his masterful studies of ancient Roman art, replete with loving descriptions of the homoeroticism found therein.[32]

- 1771 – A monk is burned at the stake in the Republic of Venice, becoming the last person in modern-day Italy to be executed for sodomy.[33] (A later execution took place 1782 in Palermo, but the executed would be posthumously pardoned.[34])

- 1797 – Giacomo Casanova writes in Histoire de ma vie about an ambassador, M. de Mocenigo and his lover, Manucci.[35]

19th century

[edit]

- 1805 – The Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Naples, and the other French client states in Europe adopt the Napoleonic Code, under which homosexuality was not a crime. Upon the end of Napoleon and Joachim Murat's reigns and the restoration of preceding monarchies in 1815, the Napoleonic code was gradually abolished and homosexuality again became a crime.[36]

- 1819 – Poetic improviser Tommaso Sgricci, after enormous theatrical successes throughout Europe, arrives in Rome to be crowned poet laureate, but his award is withdrawn at the last moment, and he is expelled from the Papal States, allegedly because of his scandalous homosexual lifestyle.[37]

- 1852 – Lesbian actress Charlotte Cushman moves to Rome with writer Matilda Hays and helps to foster there a group of independent expatriate female artists, writers and sculptors, many of whom are lesbians or bisexuals. The group, dubbed The White Marmorean Flock by Henry James, included sculptors Edmonia Lewis, Emma Stebbins, Harriet Hosmer and Anne Whitney.[38]

- 1859 – Kingdom of Sardinia's articles 420–425 of the penal code promulgated by Victor Emmanuel II, which punished homosexual acts between men (although not women).

- 1860 – Crossdressing warrior Giuseppa Bolognara Calcagno's action of heroism against the Bourbon cavalry earned her the Silver Medal of Military Valor.

- 1860 – Italy unified, resulting in sodomy laws of Sardinia being spread to the rest of the state except for the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, taking into account the "particular characteristics of those that lived in the south".

- 1887 – Zanardelli Code of Giuseppe Zanardelli removes all references to the stigmatization of homosexual people across the entire territory of Italy.

- 1889 – In Italy, homosexuality is legalised in the new Penal Code (effective 1890).[39]

20th century

[edit]

- 1919 – Sibilla Aleramo publishes a fictionalized account of her lesbian relationship with writer Cordula "Lina" Poletti in her novel Il Passagio.[40]

- 1930–1945 – Benito Mussolini's Fascist government institutes the Rocco Code, which does not cover homosexuality. The government punishes male homosexual behaviour with administrative punishment, such as public admonition and confinement; gays were persecuted in the later years of the regime.[41] Under the Italian Social Republic of 1943–45, there was an attempt to criminalise homosexuality; however, the law was never implemented and the Rocco Code survived the Mussolini government.[42]

- 1968 – After a controversial trial, writer and artist Aldo Braibanti is sentenced to nine years in prison for brainwashing (Italian: plagio) his younger male lover and another man. His lover undergoes shock treatments (conversion therapy) during 15 months in a mental institution.[43]

- 1972 – Activist Mariasilvia Spolato became the first woman in Italy to come out in a public square as a lesbian, losing her teaching license as a result. In 1971, Spolato was also a founder of Fuori!, the first homosexual organization in Italy.[44]

- 1972 – First LGBTQ public protest as activists from Fuori! demonstrate against the categorization of homosexuality as a 'sexual deviance' at the International Congress of Sexology in Sanremo.[45]

- 1974 – First gay club opened in Florence[46]

- 1979 – The first Italian Gay Pride Parade takes place in Pisa with about 500 people, as a protest against homophobic violence.[47]

- 1980 – The first nucleus of what later became Arcigay was formed in Palermo on December 9, 1980 as ARCI Gay. It is later renamed Arcigay, which becomes one of Italy's most prominent LGBT rights organizations.

- 1998 – A lesbian couple is registered by city officials in Pisa as 'a family' in their list of common-law marriages, causing condemnation by the Vatican.[48]

21st century

[edit]2000–2004

[edit]- 2002 – Franco Grillini introduces legislation that would modify article III of the Italian Constitution to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.[49][50] It is not successful.

- 2003 – Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment is illegal throughout the whole country, in conformity with European Union directives.

- 2004 – Tuscany becomes the first Italian region to ban discrimination against homosexuals[51] in the areas of employment, education, public services, and accommodations. Silvio Berlusconi's government challenges the new law in court, asserting that only the central government had the right to pass such a law. The Constitutional Court overturns the provisions regarding accommodations (with respect to private homes and religious institutions), but otherwise upholds most of the legislation.[52] Afterwards, the regions of Liguria (November 2009),[53] Marche (February 2010),[54] Sicily (March 2015),[55][56] Piedmont (June 2016),[57] Umbria (April 2017),[58][59][60] Emilia-Romagna (July 2019)[61][62] and Campania (August 2020)[63] enact similar measures.

2005–2009

[edit]

- 2004 – A police officer is reportedly fired for cross-dressing in public while off duty.[64]

- 2006 – The first transgender MP is Vladimir Luxuria, elected as a representative of the Communist Refoundation Party. While she is not reelected, she goes on to be the winner of a popular reality television show called L'Isola dei Famosi.[65]

- 2006 – Grillini again introduces a proposal to expand anti-discrimination laws, this time adding gender identity as well as sexual orientation.[50] It receives less support than the previous one had.

- 2007 – On 8 February the government led by Romano Prodi introduces a bill[66] which would grant rights in areas of labour law, inheritance, taxation and health care to same-sex and opposite-sex unregistered partnerships. The bill is never made a priority of the legislature and is eventually dropped when a new Parliament is elected after the Prodi government loses a confidence vote.

- 2007 – An ad showing a baby wearing a wristband label that says "homosexual" causes controversy. The ads are part of a regional government campaign to combat anti-gay discrimination.[67]

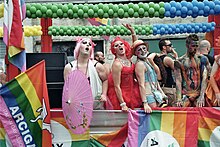

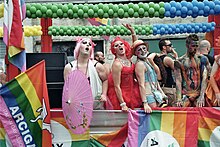

2010-07-02 Arcigay float at Gay Pride Rome, 2010 - 2008 – Danilo Giuffrida is awarded 100,000 euros compensation after having been ordered to re-take his driving test by the Italian Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport due to his sexuality; the judge says that the Ministry of Transport is in clear breach of anti-discrimination laws.[68]

- 2009 – The Italian Chamber of Deputies shelves a proposal against homophobic hate-crimes, that would have allowed increased sentences for violence against homosexuals, approving the preliminary questions moved by Union of the Centre and supported by Lega Nord and The People of Freedom[69] (although 9 deputies, politically aligned with the President of the Chamber Gianfranco Fini, voted against it).[70] The deputy Paola Binetti, who belongs to Democratic Party, voted against the party guidelines.[71]

2010–present

[edit]- 2016 – Italy approves same-sex civil unions [72]

- 2018 – A lesbian couple's baby, conceived with in vitro fertilisation, is allowed to register their son with city officials after the couple was initially told to lie about how the baby was conceived, because IVF was only recognized for heterosexual couples.[73]

- 2020 – On 19 November, the Gay Party is officially presented as the first Italian political group dedicated especially to the defense of the rights of the LGBT population.[74]

- 2021 – The Italian Parliament passes an infrastracture bill containing a provision which makes advertisements with homophobic or transphobic messages illegal to expose on streets or on vehicles. The new law comes into force on 10 November.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Penczak, Christopher (2003). Gay Witchcraft: Empowering the Tribe. York Beach: Red Wheel/Weiser. p. 11. ISBN 1-57863-281-1. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

They encircle two other bird-masked men, both with erect penises. Parallel lines connect the neck to the buttocks and ankles and the penis of one man to the buttocks of another. Thought by most scholars to be a sacrificial rite in which the parallel lines represent bindings, other interpreters see this as a homoerotic initiatory rite, with the lines possibly representing male energy, or even ejaculation.

- ^ "Timeline of more History". Archived from the original on 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ^ Sergio Musitelli, Maurizio Bossi, Remigio Allegri, Storia dei costumi sessuali in occidente dalla preistoria ai giorni nostri, Rusconi, Milano 1999, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Suetonius, Julius 2–3; Plutarch, Caesar 2–3; Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.20

- ^ Martial attests to same-sex marriages between men during the early Roman Empire, although these had no legal status; see Martial, Epigrams 1.24, 12.42

- ^ a b c d e (Fone, 2000)

- ^ a b McElduff, Siobhan. Unroman Romans: Same Sex Desire, Women. British Columbia: University of British Columbia. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Storia Nerone: quello che non leggi sui libri di storia

- ^ Dio Cassius, Epitome of Book 68.6.4; 68.21.2–6.21.3

- ^ Apologia I, 27, UTA, RANKE-HEINEMANN, Eunuchi per il regno dei cieli, Rizzoli 1990, p. 66.

- ^ Augustan History, Life of Elagabalus 10

- ^ a b c Varner, Eric (2008). "Transcending Gender: Assimilation, Identity, and Roman Imperial Portraits". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volume. 7. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press: 200–201. ISSN 1940-0977. JSTOR 40379354. OCLC 263448435.

Elagabalus is also alleged to have appeared as Venus and to have depilated his entire body. ... Dio recounts an exchange between Elagabalus and the well-endowed Aurelius Zoticus: when Zoticus addressed the emperor as 'my lord,' Elagabalus responded, 'Don't call me lord, I am a lady.' Dio concludes his anecdote by having Elagabalus asking his physicians to give him the equivalent of a woman's vagina by means of a surgical incision.

- ^ a b Tess deCarlo, Trans History (ISBN 1387846353), page 32

- ^ Godbout, Louis (2004). "Elagabalus" (PDF). GLBTQ: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Chicago: glbtq, Inc. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ Benjamin, Harry; Green, Richard (1966). The Transsexual Phenomenon, Appendix C: Transsexualism: Mythological, Historical, and Cross-Cultural Aspects. New York: The Julian Press, Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ Theodosian Code 9.7.3: "When a man 'marries' in the manner of woman, a 'woman' about to offer himself to men what does he wish (Cum vir nubit in femina, femina viros proiectura, quid capiat), when sex has lost all its significance; when the crime is one which it is not profitable to know; when Venus is changed to another form; when love is sought and not found? We order the statutes to arise, the laws to be armed with an avenging sword, that those infamous persons who are now, or who hereafter may be, guilty may be subjected to exquisite punishment." This is denunciation of these pretended marriages which had no legal force

- ^ (Theodosian Code 9.7.6): All persons who have the shameful custom of condemning a man's body, acting the part of a woman's to the sufferance of alien sex (for they appear not to be different from women), shall expiate a crime of this kind in avenging flames in the sight of the people.

- ^ Evagrius Ecclesiastical History 3.39

- ^ Justinian Novels 77, 144

- ^ Crompton, Louis (2004). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780674030060. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ PETRI DAMIANI Liber gomorrhianus, ad Leonem IX Rom. Pon. in Patrologiae Cursus completus...accurante J.P., MIGNE, series secunda, tomus CXLV, col. 161; CANOSA, Romano, Storia di una grande paura La sodomia a Firenze e a Venezia nel quattrocento, Feltrinelli, Milano 1991, pp.13–14

- ^ John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality (1980) p. 293.

- ^ Elliott, Dyan (2020-11-27). The Corrupter of Boys: Sodomy, Scandal, and the Medieval Clergy. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9748-5.

- ^ storia completa qui Archived 2015-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ della Chiesa, Angela Ottino (1967). The Complete Paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. p. 83.

- ^ Armstrong, George (November 2, 1997). "Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "Il Sodoma". Encyclopædia Britannica..

- ^ Eisenbichler, Konrad. "Laudomia Forteguerri: Constructions of a Woman." The Sword and the Pen: Women, Politics, and Poetry in Sixteenth-century Siena. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2012. 101-64.

- ^ Mutini, Claudio. "Campiglia, Magdalena". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Giannetti, Laura (2010). "Female-Female Desire in Italian Renaissance Comedy". Renaissance Drama. 36–37: 99–125. doi:10.1086/rd.36_37.41917455. JSTOR 41917455. S2CID 191373362. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Marcocci, Giuseppe (Summer 2015). "Is This Love? Same Sex Marriages in Renaissance Rome". Historical Reflections. 41 (2): 37–52. JSTOR 24720593. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Kuzniar, Alice A. (1996). Alice A. Kuzniar (ed.). Outing Goethe and His Age. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 9–16. ISBN 0804726140. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Dynes, Wayne R.; Donaldson, Stephen (1992). History of Homosexuality in Europe and America. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0550-7.

- ^ Tartamella, Enzo (2003). Rapito d'improvvisa libidine. Storia della morale, della fede e dell'eros nella Sicilia del Settecento (in Italian). Trapani: Maroda. p. 190.

- ^ Casanova, Jacques (1894). The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova. Arthur Machen. Privately Printed.

- ^ Benadusi, Lorenzo, et al. “Chapter 5.” Homosexuality in Italian Literature, Society, and Culture, 1789-1919, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017, pp. 115–119.

- ^ "SGRICCI, Tommaso". Enciclopedia Italiana (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- ^ Merrill, Lisa (July 2003). "Old-maids, Sister artists, and Aesthetes". Women's Writing. 10 (2): 367–383. doi:10.1080/09699080300200194. S2CID 161611637. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News Online. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Cenni, Alessandra (2015). "Poletti, Cordula". Treccani (in Italian). Rome, Italy: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ (in Italian) L’omosessualità in Italia Archived 2008-08-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "glbtq >> social sciences >> Italy". 2011-11-03. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ^ Turrini, Davide (April 9, 2014). "Aldo Bribanti, Morto L'Intelletuale condannato per aver 'plagiato' due ragazzi". Il Fatto Quotidiano. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ E' morta Mariasilvia Spolato prima italiana a dichiararsi omosessuale (in Italian)

- ^ Onuitalia (28 June 2021). "Italy Recalls Its Stonewall, Commits to Defend Equal Rights". OnuItalia.com. United Nations Italia. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Club Tabasco". Retrieved 2023-01-26 – via Tumblr.

- ^ Redazione. "Pisa 1979: la Stonewall Italiana, il primo gay pride". Gay Italia. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Lesbians Register Relationship". Off Our Backs, A Women's News Journal. 28 (9). October 1998. JSTOR 20836183. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Pedote, Paolo; Nicoletta Poidimani (2007). We will survive!: lesbiche, gay e trans in Italia. Mimesis Edizioni. p. 181. ISBN 9788884835673.

- ^ a b Borrillo, Daniel (2009). Omofobia. Storia e critica di un pregiudizio. Edizioni Dedalo. p. 155. ISBN 9788822055132.

- ^ Text of Legislation (in Italian) Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Text of Decision (in Italian) Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Articolo » Raccolta Normativa Regione Liguria". Regional Government of Liguria. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- ^ "Consiglio regionale delle Marche -". Regional Government of Marche. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- ^ "Approvata legge contro l'omofobia, risultato storico per la Sicilia". 6 March 2015.

- ^ Correnti, Giuseppe (5 March 2015). "Arcigay Palermo: "legge contro l'omofobia è un risultato storico"".

- ^ Legge regionale n. 5 del 23 marzo 2016 (Vigente dal 18/12/2018)

- ^ "Approvata legge regionale anti-omofobia - Umbria". ANSA.it. 4 April 2017.

- ^ "Approvata legge contro l'omotransfobia, dall'Umbria riparte la lotta alle discriminazioni". 4 April 2017.

- ^ "Dopo 10 anni una legge contro tutte le discriminazioni - Piemonteinforma". www.regione.piemonte.it. October 2019.

- ^ "Emilia-Romagna: approvata la legge contro l'omo-transfobia". Arcigay.it (in Italian). 30 July 2019. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- ^ "Legge Regionale Contro le DIcriminazioni e le Violenze Determinate dall'Orientamento Sesuale o Dall'Identità di Genere" [Regional Law Against Discrimination and Violence Motivated by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity] (in Italian). Regional Government of Emilia-Romagna. Retrieved 2021-10-30.

- ^ "Omotransfobia, la Regione Campania approva la legge. Arcigay: "Dalle Regioni un impulso al Parlamento"". Arcigay.it (in Italian). 6 August 2020. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- ^ "Cross-dressing Italian cop given the boot". UPI. 29 December 2006.

- ^ "Luxuria: "Ora la sinistra mi critica ma vado avanti"" (in Italian). il Giornale. 25 November 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ "Italy may recognise unwed couples". BBC News Online. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ "Gay newborn poster sparks row in Italy". Reuters. 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Italian wins gay driving ban case". BBC News. 13 July 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ "Camera affossa testo di legge su omofobia". Reuters (in Italian). 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ "Omofobia, testo bocciato alla Camera E nel Pd esplode il caso Binetti". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 13 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ "Omofobia, la Camera affossa il testo Caos nel Pd: riesplode il caso Binetti". La Stampa (in Italian). 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ Povoledo, Elisabetta (11 May 2016). "Italy Approves Same-Sex Civil Unions". The New York Times.

- ^ Jackman, Josh (April 23, 2018). "Lesbian Couple's IVF Baby Recognized For the First Time in Italy". The Pink News. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Arriva il primo Partito Gay per i diritti Lgbt: "Stanchi di delegare in questo momento d'emergenza"". Fanpage.it (in Italian). 19 November 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2021.