History of Italian culture (1700s)

| Art of Italy |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Centennial divisions |

| Important art museums |

| Important art festivals |

| Major works |

|

| Italian artists |

| Italian art schools |

| Art movements |

| Other topics |

The 1700s refers to a period in Italian history and culture which occurred during the 18th century (1700–1799): the Settecento.[1] The Settecento saw the transition from Late Baroque to Neoclassicism: great artists of this period include Vanvitelli, Canaletto and Canova, as well as the composer Vivaldi and the writer Goldoni.

Characteristics

[edit]The Settecento is a word today commonly used to describe this period Italy.

The first decades of the Settecento saw the ultimate end of the Renaissance movement in Italy, and the last development of the Counter-Reformation and Baroque era, and also the beginning of the Italian Enlightenment.

In the 18th century, the political and socio-cultural condition of Italy began to improve, under Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, and his successors. These princes were influenced by philosophers, who in their turn felt the influence of a general movement of ideas at large in many parts of Europe, sometimes called the Enlightenment. All this led to a cultural revival in the 18th century's second half: the Age of Reason and Reform.

Politically Italy suffered mainly because of the crisis of the Republic of Venice, but in the last years of Settecento Napoleon Bonaparte brought the French Revolution ideals to Italy and created in 1797 the first unitarian state in the peninsula since the early Middle Ages: the Cisalpine Republic, that in 1804 became the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy.

Architecture

[edit]The 18th century saw the capital of Europe's architectural world transferred from Rome to Paris. The Italian Rococo, which flourished in Rome from the 1720s onward, was profoundly influenced by the ideas of Borromini. Notable architects active in Rome were Francesco de Sanctis (Spanish Steps, 1723) and Filippo Raguzzini (Piazza Sant'Ignazio, 1727), while about the Sicilian Baroque, notable architects were Giovanni Battista Vaccarini, Andrea Palma.

Luigi Vanvitelli was among the most prominent architects of Italy during this century, he built the Palace of Caserta at the request of Charles VII of Naples and worked on many other palaces and buildings like the Royal Palace of Naples the Royal Palace of Milan and the Basilica of Santissima Annunziata Maggiore.

-

Caserta Palace

-

Palazzina di caccia of Stupinigi

-

Basilica of Superga

-

Royal Villa of Monza

-

The Trevi fountain in Rome

Sculpture

[edit]In the 18th century much sculpture continued on Baroque lines: the Trevi Fountain was only completed in 1762 after 30 years. Rococo style was better suited to smaller works, and arguably found its ideal sculptural form in early European porcelain, and interior decorative schemes in wood or plaster.

Music

[edit]Antonio Vivaldi was the most important composer in Italy at the end of the Baroque period. He wrote more than 400 concertos for various instruments, especially for the violin. The scores of 21 operas, including his first and last, are still intact. His best known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons.

Johann Sebastian Bach was deeply influenced by Vivaldi's concertos and arias (recalled in his St John Passion, St Matthew Passion, and cantatas). Bach transcribed six of Vivaldi's concerti for solo keyboard, three for organ, and one for four harpsichords, strings, and basso continuo based upon the concerto for four violins, two violas, cello, and basso continuo.

Literature

[edit]Carlo Goldoni (1707-1793) was the most important Italian literate of the Settecento. He produced over 150 comedies. Giambattista Vico and Lodovico Muratori were the most notable Italian historians of this century, while the leading figure of the literary revival in poetry was Giuseppe Parini.

Count Vittorio Alfieri (1749-1803) was an Italian dramatist and poet, considered the "founder of Italian tragedy."[2] Alfieri is often indicated as one of the precursors of the Romanticism in Europe.

Philosophy

[edit]

Italy was affected during the Settecento by the "enlightenment", a movement which was a consequence of the Renaissance and changed the road of Italian philosophy.[3] Followers of the group often met to discuss in private salons and coffeehouses, notably in the cities of Milan, Rome and Venice.

Cities with important universities such as Padua, Bologna and Naples, however, also remained great centres of scholarship and the intellect, with several philosophers such as Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) (who is widely regarded as being the founder of modern Italian philosophy)[4] and Antonio Genovesi.[3] Italian society also dramatically changed during the Italian Enlightenment. The church's power was significantly reduced, and it was a period of great thought and invention, with scientists such as Alessandro Volta and Luigi Galvani discovering new things and greatly contributing to Western science.[3]

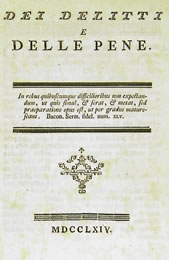

Cesare Beccaria was also one of the greatest Italian Enlightenment writers, who was famous for his masterpiece Of Crimes and Punishments (1764), which was later translated into 22 languages.[3] In it, Beccaria put forth some of the first modern arguments against the death penalty. His treatise was also the first full work of penology, advocating reform of the criminal law system. The book was the first full-scale work to tackle criminal reform and to suggest that criminal justice should conform to rational principles.

As a consequence in Italy, the first pre-unitarian state to abolish the death penalty was the Grand Duchy of Tuscany as of November 30, 1786, under the reign of Pietro Leopoldo, later Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II. So Tuscany was the first civil state in the world to do away with torture and capital punishment. In 2000, Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on 30 November to commemorate the event. The event is commemorated on this day by 300 cities around the world celebrating Cities for Life Day.

See also

[edit]- Italian Enlightenment

- Italian Rococo art

- Italian Rococo interior design

- Cities for Life Day

- Duecento – the 13th century in Italian culture

- Trecento – the 14th century in Italian culture

- Quattrocento – the 15th century in Italian culture

- Cinquecento – the 16th century in Italian culture

- Seicento – the 17th century in Italian culture

- Ottocento – the 19th century in Italian culture

References

[edit]- ^ "Italiano - Il Settecento ~ Il secolo dei Lumi - Tesina di S. Pelligra". www.wikisicily.com.

- ^ Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

- ^ a b c d "The Enlightenment throughout Europe". history-world.org. Archived from the original on 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "History of Philosophy 70". maritain.nd.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2013-10-13.