Jagiellońska Street, Bydgoszcz

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: organization and formatting. (April 2024) |

| Bydgoszcz | |

|---|---|

First buildings on the southern side | |

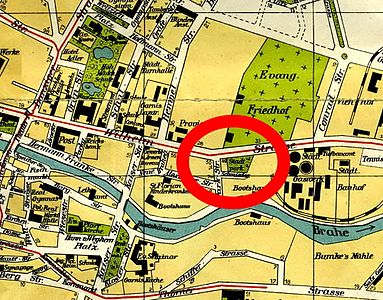

Jagiellońska Street underlined in red | |

| Native name | Ulica Jagiellońska w Bydgoszczy (Polish) |

| Former name(s) | Weg von Pohl[nische] Vordon - Der Weg von Vordon - Wilhelmstraße - Hermann-Göringstraße - Generalissimusa Stalina |

| Namesake | Jagiellonian Kings of Poland |

| Owner | City of Bydgoszcz |

| Length | 2.2 km (1.4 mi) |

| Location | Bydgoszcz, Poland |

Jagiellońska Street is a historic street in the centre of Bydgoszcz in Poland.

Location

[edit]

The street is located in the heart of Bydgoszcz. It stretches on an east-west axis, from Fordon roundabout to the intersection with Gdańska Street. It is approximately 2.2 km long. Jagiellońska Street joins the Old Town and Downtown district of Bydgoszcz.

History

[edit]The Jagiellońska Street is on the path of a medieval communication route between Bydgoszcz castle and Fordon on the Vistula river: since the mid-13th century, the only permanent crossing of the Brda river was the bridge of Bydgoszcz Old Town where customs duties were collected. This road was leaving the town from the "Gdansk Gate" and was running eastward following the northern side of the Brda river. In Fordon, it was possible to cross the Vistula river to get to Chełmno Land or follow northeast along the Lower Vistula valley towards Swiecie and Gdańsk.

The course of the road, coinciding with the current street, is visible on the oldest known plan of Bydgoszcz, by Swedish Count Erik Dahlbergh in 1657.[1] In the 17th–18th century, the road was connected with the farming cities and villages located in the east: Grodztwo, Bartodzieje, Zimna Woda, Bartodzieje Małe and Fordonek.

In 1867, the village of Grodztwo was incorporated into Bydgoszcz territory, pushing further east the limit of the town (in the area of today's Oginski Street). Another extension of the borders occurred in 1920, reaching current city borders: the ancient medieval path is now covered by Jagiellońska and Fordonska streets course.[2] During the interwar period, Jagiellońska Street ended on Maximilian Piotrowski Street, the eastern remaining path being called "Promenade street".

The development of Jagiellońska Street as an important and chic area started in the 1830s, with the construction of grand edifices like the building by Prussian administrative authorities of the Regional Office (Polish: Budynek Urzędu Wojewódzkiego). Later on, Grodztwo section gradually became an official area, with administrative, educational and cultural activities. In 1840, the axis so far called "road to Fordon" (German: Der Weg von Vordon) was named Wilhelmstrasse in honor of the King Frederick William IV of Prussia. In 1870-1872, the construction of a new steel bridge on the Brda river, the Bernardyńska Street was created, joining Jagiellońska and the river.

In the second half of the 19th century a number of official buildings have been erected along the street, such as:

- The military hospital (1850–1852), now the building of the University of Medicine UMK in Bydgoszcz;

- The Reichsbank building (1863–1864), now local seat of the National Bank of Poland (NBP);

- The municipal School for Boys, German: Bürgerschule (1872), now an administrative building of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship;

- The Civic School for Girls, German: Städtische mitlere Töchterschule (1875–1878), now the School of Fine Arts in Bydgoszcz;

- The Main Post Office building (1896–1899).

At the same period, on the eastern limit of Bydgoszcz, hence in the vicinity of Jagiellońska Street, other urban edifices have been erected:

- The gas workplant (1860);

- The city slaughterhouse (1893).

Some buildings have been designed by famous architects of their time, like Bydgoszcz-born Józef Święcicki or Heinrich Seeling from Berlin.

After World War II, the increasing traffic along the axis has required to enlarge the street. Between 1969 and 1973, prolonging this avenue led to the creation of Fordońska street to the east, improving traffic conditions in this area of Bydgoszcz. In 1974, the completion of the streets modernization also allowed Jagiellońska and Focha streets to have a dual carriageway with a middle track for trams, in addition Jagiellonska roundabout was built with an underground passage for pedestrians.[3]

In 2013 the University Bridge was built, crossing over Jagiellońska Street and the Brda river on a north-south axis.

Naming

[edit]Jagiellońska Street bore the following names:[4]

- 1797 - Weg von Pohl Vordon

- 1800 - Der Weg von Vordon

- 1840–1920 - Wilhelmstraße

- 1920–1939 - Jagiellońska Street

- 1939–1945 - Hermann-Göringstraße

- 1945–1949 - Jagiellońska Street

- 1950–1956 - Generalissimo Stalin

- From 1956 - Jagiellońska Street

Means of communication

[edit]First tram tracks on Jagiellońska Street was built in 1901, at the creation of the third electric tram line (line "C" blue), from Wilczak to Skrzetusko. In 1904, the line was extended eastward to Bartodzieje, as the longest tram line (5.4 km) in the city.[5] Between 1972 and 1974, in connection with the expansion of Jagiellońska Street, the single-track line was converted into a two-way one.[6]

Currently on the street run the following tram lines:

- From Focha Street to Jagiellońska roundabout, Nr.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8;

- From Jagiellońska Street to Fordońska Street, Nr. 2, 3, 4 and 8.

Architecture

[edit]Jagiellońska Street is one of the most important and most representative streets of Bydgoszcz. Buildings standing in the Old Town section of the street, from Gdańska Street to Jagiellońska roundabout, date back to the Prussian era. Main historical buildings from this period include the building of the Regional Office, the Main Post Office, the National Bank of Poland seat in Bydgoszcz.

The Church of the Poor Clares displays Gothic and Renaissance features.

The eastern section (from Jagiellońska roundabout to Fordon) possesses less historic buildings and more international style buildings from 1945 and after. The most numerous buildings represent the end of 19th-beginning of 20th century and the modern period.

Main places and buildings

[edit]Poor Clares' Church, at 2 Gdańska Street, corner with Jagiellońska Street

[edit]Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship heritage list, Nr.601229 Reg.A/209 (31 March 1931)[7]

1582–1602 & 1618–1645

The oldest building in Gdańska Street, it has been used as a warehouse and a fire station during Prussian times.

-

View from Theatre square

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

View from Gdańska Street

Drukarnia shopping mall, at 1

[edit]2007, by JSK Architects

At this location was one of the biggest printhouse in Poland.

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

Main entry on Gdańska Street

Savoy Building, at 2, corner with Theatre square

[edit]1913

Modernism, by Rudolf Kern

This tenement stands at the corner of Jagiellońska Street and Theatre Square. From 1789 to 1800, on the place were a storehouse and stable. In 1853, a new building was erected, which survived until 1912. In that year a new edifice was built by Rudolf Kern, following a design of architect Heinrich Gross: the client was Otto Pfefferkorn, owner of a successful furniture factory[8] and a tenement in Gdanska street. Minor works have been performed in 1922-1923. In 1940, arcades designed by Jan Kossowski have been added at ground level at the request of the Nazi authorities: the project comprised also the opposite building with the same features.

The address has housed for a long time the Alliance Française offices of Bydgoszcz. Today, the place is famous for the night club "Savoy" that occupies a whole floor.[9] In 1999, a commemorative plaque for Stanisław Niewitecki (1904-1969), a famous Polish numismatist who lived in Bydgoszcz.[10]

-

View from Jagiellońska-Gdańska Streets crossing

-

Elevation onto Jagiellońska St.

-

Detail of the roof

-

Plaque to Stanisław Niewitecki

Regional Office Building, at 3

[edit]Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship heritage list, Nr.601346-Reg.A/871 (29 October 1956 & 20 October 1959).[11]

1834–1836[12]

The oldest buildings of the Regional Office was built between 1834 and 1836 as the seat of a Prussian region (Polish: Rejencja), an administrative unit established in 1815 within the Grand Duchy of Posen. Before its construction, officials of the Netze District have been meeting in the 1778-building on the Old Market Square (now the Provincial and Municipal Public Library). The development of the institutions required a new administrative building.[13] The foundation stone of the building was laid on 8 June 1834. The construction was carried out in two years two years under the supervision of Carl Adler, advised by Karl Friedrich Schinkel working in Berlin. Construction manager was Friedrich Obuch, a Bydgoszcz regency councilor.[14]

In the years 1863–64, the building was extended by two small avant-corps on each side. In 1898–1900, the edifice was partially reconstructed and added four wing in the corners, under the supervision of Mr Busse, a national project building inspector.[15] Originally in the basement were located the housing and laundry services, the lithography facility and the fuel storage. On the ground floor were set bureaus, offices, the cadastre district department and the finance branch. On the first floor, in addition to the presidential salon, there were a reading room, a library and a conference room. School, tax and forestry departments were housed on the second floor and in the attic.[14] When Bydgoszcz joined back Polish territory in 1920, Prussian administration was liquidated, the now disused building housed, among others, the Regional Directorate of State Forests, the Accounting Chamber of Control of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs, the Regional Tax Office, the county School Inspectorate and the Inspectorate of Labour. In 1938, Bydgoszcz city became the capital of Pomeranian Voivodeship and the building housed its administrative services. During the Nazi occupation, German authorities reactivated Bydgoszcz "Rejencja" within the District of Gdańsk-West Prussia and used the edifice accordingly. After the liberation of Bydgoszcz in March 1945, the building was constantly the provincial seat of the Polish authorities. From 1945 to 1950, it housed the Bydgoszcz Voivodeship, between 1950 and 1975 the Provincial Bureau of National Council, from 1975 to 1998 the Provincial Office and the Local assembly of the Bydgoszcz Province. Since the administrative reform of 1999, it is the seat of Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship. In the 1960s, the construction was expanded with side-buildings, connected by a pedestrian covered bridge:[15]

- A Conference hall (1960–1963), built on the back of the historical building, on a design by architect Tadeusz Czarniawski,

- A building on Konarski street (1962-1965) by architect Jerzy Jerka,

- A 14-storey office building on the corner of Jagiellońska and Konarski streets (1966-1969) by architect Bronislaw Jablonki.[15]

The building was erected on the plan of an elongated rectangle, with four wings at the corners. The oldest, central body displays of Neoclassical characteristics, later avant-corps and wings present eclectic features.[15] The building has a symmetrical shape. It comprises a basement, two-storey with an attic covered with gable roofs. The front part main entrance is incorporated into a slight avant-corps. The ground floor is decorated with bossage, and the front elevation is crowned with an advanced profiled cornice, supported by a range of corbels.[16] The interior has preserved the original layout of the rooms. The staircase is to be noticed, with its openwork balustrade. In the north east wing, the ground floor still possess Tuscan marble columns from the time of construction.[14] Before the main edifice stands:

- A stone memorial (1998), commemorating March 1981 events in Bydgoszcz,

- Two ailanthus trees, over 250 cm diameter wide each, recognized as city's Natural monuments.[17]

-

The building in 1910

-

Main elevation

-

Back side view from Casimir the Great Park

-

Stone memorial

Emil Werckmeister tenement, at 4

[edit]End of 19th century[12]

Eclecticism in architecture, Neo-Mannerism, Neo-Baroque

The building was erected at the end of the 19th century on the site of demolished granaries where was housed since 1907 the winery "Werckmeister". Emil Werkmeister commissioned architect Heinrich Seeling from Berlin to realize the project.[18] In 1920, the building was purchased by Bydgoszcz's Municipal Savings Bank (Polish: Komunalną Kasę Oszczędności), which performed internal modernization works.[18] In 1938, the building was expanded with enlarged wings and outbuildings designed by Jan Kossowski, creating a single, closed bank complex.[18] Today, the ground floor houses the local seat of Millennium Bank while upper levels are privately owned.

The tenement presents eclectic forms, with Neo-Mannerism and Neo-Baroque elements.[16] It has a Mansard roof and an attic. In the corner with Pocztowa street stands a two-storey bay window topped by a tented roof onion with a finial.[16] Facades are decorated with rich architectural details like friezes between floors or cornices.[16] The bay window is adorned with a graphic solar motif, often used by Heinrich Seeling in his other projects.[18] The same motif is also visible in other parts of the facade (gables, friezes under the windows).

-

The building once completed ca. 1910

-

Facades onto Jagiellońska and Pocztowa St.

-

Detail of gable

-

Bay window with solar motif

-

Detail of the onion tented roof

Main Post office, at 6

[edit]Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship heritage list Nr.601347-Reg.A/749 (15 December 1971).[7]

1883–1899

Buildings stand on a plot delimitated by the following streets: Jagiellońska, Stary Port, Pocztowa and Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki in Bydgoszcz. They have been erected on the northern bank of the Brda river.

-

View from the river

-

Facade onto Jagiellońska St.

-

By night

National Bank of Poland (NBP) building, at 8

[edit]1863-1866[12]

The building at Jagiellońska street 8 houses the historic edifice of the National Bank of Poland in Bydgoszcz.

-

Reichbank building ca 1901

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

View from Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki street

Building at 9, corner with Konarskiego Street

[edit]1872[12]

The building was erected in 1872 on a design by architect von Müller[19] to house the civic school for boys (German: Bürgerschule). The school was located in the former Bydgoszcz's Carmelites monastery. It was an elite folk school, with a 9 years cycle, and pupils usually belonged to wealthy high society, rich enough to pay the high tuition fees.[20] In 1884, the Bügerschule moved to a building in Stanisław Konarski street, where is located today the Bydgoszcz School of Fine Arts.[4] In the 1990s, the building housed the Foreign Language Teacher Training College, which then moved to a building in Dworcowa Street. Since 2010, the seat of the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Centre for Education and Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Marshal's Office in Bydgoszcz are located there.

On the sidewalk grows a ginkgo identified as natural landmark of Bydgoszcz.[21]

The building boasts historicism features, with a predominant Neoclassical architecture form. It has a "L" shape, with a prominent avant-corps in the middle of its frontage, with two storey, an attic and a basement. The entrance double portal is topped with a triangular pediment and a tympanum in which is placed a circular ornament. The facade is divided by horizontal cornices and a wide frieze on its top. The ground floor is decorated with bossage.[16]

-

The building ca. 1915

-

Today, view from Jagiellońska street

-

Zoom on the portal

-

The avant-corps and its pediment

Building at 10

[edit]1862–1866[12]

This house from the 2nd half of the 19th century houses since the beginning of the 20th century the Bydgoszcz Chamber of Craft (Polish: Izba Rzemiosła), before it moved to Piotrowskiego street. Today it gathers crafts from the whole Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship. The building also houses the local seat of Polish Weigh and Measure office.

The edifice has undergone serious architectural changes after World War II and the restorations that followed: loss of facades balconies and eclipse of the gable and roof pilasters. In 2003, a frontage renovation brought back Art nouveau colorful floral ornaments.

-

"Izba Rzemiosła" in 1938 with original facade

-

Current view from Jagiellońska street

-

Floral ornament paintings of the frontage

-

Adorned portal

UKW building at 11

[edit]1946, by Jan Kossowski[22]

The edifice was designed by local architect Jan Kossowski.[22]

It houses the following departments of the Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz (Polish: Uniwersytet Kazimierza Wielkiego w Bydgoszczy-UKW):

- Faculty of Humanities;

- Institute of Polish Philology and Cultural Studies.

-

View from the street

City Hotel at 6 3 Maja street

[edit]1992

A 4-star hotel, equipped in particular with conference and banquet rooms, a restaurant, a bar, a casino and a hairdressing salon.[23]

-

View from 3 Maja street

Building at 12

[edit]1877[12]

The house at then Wilhelm Straße 59, was a renting tenement owned by the famous Blumwe family. Wilhelm and Karl Blumwe had a factory at today's Nakielska 53. They also had their own villa built on Gdańska Street, at Nr.50.

The building shows nice architectural details

- On the ground floor, a delicate double wrought iron gate and plastered corbels overhanging the street;

- A grand bay window strats on the first floor, flanked by windows capped by decorating masks;

- All over the upper floors, friezes and plastered ornaments teem on the facade surface, with vegetal motifs.

The top ogee gable is equally decorated.

-

main elevation

-

Facade detail

-

Western elevation

-

Gates detail

Medical College Buildings, at Nr.13/15

[edit]1850–1852

The building was erected between 1850 and 1852, as Bromberg hospital garrison. It was located then at the crossroads of Wilhelmstrasse and Hempelstrasse. The latter was marked with a wall of brick, whereas the former had a fence with iron wrought bars with a gate and a wicket.[24] The main building, U-shaped, was a monumental edifice of brick facades, with a three-storey body, flanked by 2 avant-corps in its corners: they were higher than the facade and topped with battlements, like medieval towers. Originally the building had a symmetrical facade along a two-storey avant-corps topped with battlements, where was located the main entrance,[24] and three extra barracks for the sick. Additional elements were built regularly until 1910:

- In the back of the lot in 1881 an outbuilding was constructed;

- In 1890–91, a new western edifice part housed hospital administration and direction;

- In 1910, a new, ground-floor morgue was built.[24]

In 1919, with the re-birth of the Polish state, municipal authorities took over the hospital from the Prussian forces. The size of Bydgoszcz garrison and the proximity with the fighting area of Polish–Soviet War increased significantly the activity of the institution: in 1920, under the command of Poznań General District, the medical capacity of the institution reached the maximum amount of 1,140 beds.[24] After the conflict, the number of hospitalized patients steadily decreased: 320 beds (1922), 300 beds (1923) and 200 beds (1924–25).[24] In 1928, Toruń military authorities decided to stop the activity of the hospital, which had only 100 beds left, keeping only the District Hospital in Toruń. In this way, Bydgoszcz remained without Military medical Department till 1939.[24]

During Nazi occupation, the building was used as a German military hospital.[24]

After the liberation of Bydgoszcz, from 26 January to 10 February 1945, hospital buildings accommodated a Mobile Field Surgical Hospital of the Polish Army. In 1948, a huge renovation occurred, including the expansion of the main building and the demolition of five minor edifices. The renovated complex housed the Provincial Council of Polish Communist Party[24] till the end of the communist era.

In 1990, the edifice became the property of the Regional Treasure Department:[24] at that time, several buildings passed under the ownership of the Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, which located here offices of the rector, two deaneries, college administrators, some classrooms, a cafeteria and an additional dormitory.[25] Around 2000, with Tax and Revenue office leaving the premises, the whole building fell under the responsibility of the University.

From the former buildings of the garrison hospital, only the U-shaped footprint is left. It was initially constructed in the style of historicism, using forms of Neo-Romanesque. Its appearance resembled a fortress, but these stylistic features have been lost during the complex reconstruction carried out in 1947-1948,[24] which also wiped away the avant-corps, changed the size and shape of the windows, added a fourth floor and extended the gable to the whole edifice.

-

Garrison Hospital in 1865, with its original features

-

Current view of N.13/15 from Jagiellońska street

-

N13/15 from Jagiellońska roundabout

Bank Pocztowy Building, at 17

[edit]1968

The building was constructed on a design of architect Henry Micuły. In the vicinity stood buildings from 1817: a Prussian warehouse for spare parts and the arsenal, destroyed by an explosion.[26] Since 1990, it houses the national seat of "Bank Pocztowy", whose shareholders are the Polish Post (75%) and PKO BP (25%).

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

View by night

1991–1992

The building houses Bydgoszcz branch of "Bank Handlowy in Warsaw, now Citibank. It was designed by Kurt Roessling from Steckel & Roggel Baugesselschaft company.[27]

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

View from Jagiellońska roundabout

Youth Palace, at 27

[edit]1970–1974

Palace of Youth construction is an initiative of the civil society of Bydgoszcz in 1969. At the time the project was called Social Committee for the Construction Youth Culture, Technology and Sport (Polish: Społeczny Komitet Budowy Młodzieżowego Domu Kultury, Techniki i Sportu).[28] Architects were Z. Lipski, J. Sadowski and J. Wujek, supported by Engineer Bernard Majchrzak.[15] The construction began on 20 July 1969,.[29] and lasted 6 years: alongside building companies, young people ad pupils also participated to the project reusing bricks coming from on- site ruined 19th century Prussian warehouse Offices. The 6000 m2 facility was officially inaugurated on 22 July 1974.,[28] its first director being Dorothy Kempka.[29] The complex took the name of "Youth palace-Jan Krasicki" ((in Polish)Pałac Młodzieży im. Janka Krasickiego), a youth activist and member of the Polish Workers' Party (1919-1943), from 1977 to 1990. In 2009, the building has undergone a refreshing of its facade. In 2015, discussions started to plan a major renovation of the facility.[30] In mid-2019, thermomodernization works of the building were completed: outside facades were completely insulated and gained a new aesthetic look in shades of white and gray and a 18-KW photovoltaic installation was set up on the roof.[31]

In the Palace of Youth, particular attention has been paid from the beginning to the standard of its equipment and the selection of experienced staff. This characterics has led to the rapid development of various forms of work with young people.[28] From the first days on, the Palace established a number of laboratories and specialized sections (art, technics, sport, science, clubs), explaining the success of the institution: during its first year (1974-1975), it welcomed 2800 young participants in 3 departments (Song and Dance, Sports and Mass Event). In the following years, within the five departments, 4000 children took part to the activities.[29] Regularly, the sections are redefined to be in line with the interests of the young audience.[28] In the 1970s, the Palace became the coordinating point of youth events in Bydgoszcz Voivodeship.[28] In 1977 the facility organized and housed the first international festival Bydgoszcz Musical Impressions (Polish: Bydgoskie Impresje Muzyczne), with teams from the Eastern Bloc, France and Sweden. Soon this event has found a permanent place in the calendar of Festivals in Bydgoszcz, while the Youth Palace received numerous awards, diplomas and awards for it.[28] "Bydgoszcz Musical Impressions" is still active today.[32]

Since its inception the Youth Palace operates in the building at Jagiellońska Street 27. The area of the building is 7600 m2 distributed among three floors with the following equipments:

- A theater hall seating 260;

- A coffee bar with 100 seats;

- A gymnastics hall;

- An indoor swimming pool;

- A dance training hall;

- A laboratory of foreign languages;

- Several lecture rooms and laboratories (painting, photography, embroidery and sewing, theatre, vocal, radio and television etc.);

- Clubrooms.[29]

Since 1974, the institution manages a Watersport Club "Copernicus" located on the Brda river[28] and since 2006 a Rowing Club[33]

Before the building is growing a catalpa tree, with a circumference of 135 cm, recognized as Bydgoszcz Natural Monuments.[34]

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

View from Ludowy Park

-

Frontage inscription

Ludowy Park

[edit]1953

The park is located between the streets Jagiellońska, Piotrowskiego and Markwarta. It was named in memoriam of Wincenty Witos. Ludowy Park ("People's Park") was founded at the place of an ancient cemetery,[35] dating back to 1778, when the first Protestants established in the city.

After Bydgoszcz's liberation in 1945, the old cemetery was closed and transferred to the Lutheran cemetery in Zaświat Street.[36] Once the cemetery liquidated, a city park, named "People's Park" (Polish: Ludowy park), was set up on the very place, using part of the remaining elements of the gone necropolis. In 2020, during the renovation of the park, it was estimated that 80,000 bodies are still buried beneath the park.[37]

-

View of a walkway

-

Monument to Wincenty Witos

-

Playground

Franz Bauer Tenement, at 30

[edit]Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship heritage list, Nr.601348 Reg.A/853/1-2 (27 December 1995).[7]

1895–1896, by Józef Święcicki[38]

The tenement was built for a restaurateur, Franz Bauer,[39] who had his activity there (then "49 Wilhemstrasse") until 1910, when he sold it to Rober Neuman,[40] another restaurateur. After 1920, there were two eatery commerces, run by Andrzej Walicki: "Bagatela" and "Pod Hallerem".[41]

During the German occupation, a club for soldiers was established there, and after the war Julian, Andrzej's son, managed a restaurant bar called "Parkowy", which was taken over by state owned company "Bydgoskie Zakłady Gastronomiczne" (Polish: Bydgoszcz Gastronomy Establishments). After the fall of communism, the building returned to the hands of Walicki's family in the 1990s.[41] In 1994, an asian restaurant, "Rong Vang", opened and is still operative today at this address.[42]

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

View of the opposite corner

-

Main facade

-

Detail of the facade

Park "Władysław II Jagiełło"

[edit]0,5 ha

1844

The park is delimited by streets Jagiellońska and Uroczą, and by the Brda river to the south. Its current area is only 50x100m, reduced by the presence of a post war building of the Polish Federation of Engineering Associations (Polish: Naczelna Organizacja Techniczna NOT). The park was founded in 1844, with an area of 0.7 ha. Its original name was "Town Park" (German: Stadt Park).[35] The main entrance was from Jagiellońska street, and comprised a garden with a large lawn adjacent to the Brda river. In the early 20th century, the park was separated from the river by low buildings.[35]

A general reconstruction took place in 1929-1930 when the park was renamed after Władysław II Jagiełło: a granite fence and a rose flowered trellis were built along Jagiellońska street, a second entrance was created on Uroczą street.[35] The main attraction of the area was a large fountain with a paddling pool. In 1939, the foliage on Jagiellońska street was so dense that one could not see the center of the park from the street.[35] Just before the outbreak of World War II, 45 species of trees and shrubs were growing in the park.[35] On 16 February 1974, in the southern part of the area was built the Bydgoszcz House of Technology or Dom Technika NOT (Polish: Naczelna Organizacji Techniczny, Polish Federation of Technics), by architect Stefan Klajbor,[43] and in the eastern part, from 1973 to 1975, have been erected offices.[44] The remaining plot is used as a square, in the middle of which was a fountain, which served as an open pool: today it is a flowered area. Sculptures also adorns the garden.[45]

-

1914 Map of Bromberg with the "Stadt Park" in front of the Lutheran cemetery (Evang. Friedhof)

-

The park and "NOT" building from the street

-

View of one of "NOT" building

-

Park Władysław II Jagiełło Bydgoszcz

-

Building "Dom Technika NOT"

-

Advertising for "Dom Technika" in 1994

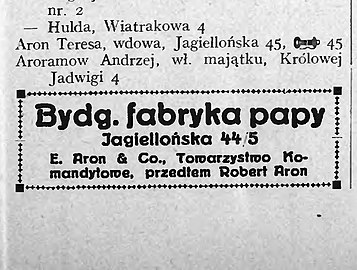

Robert Aron Tenement, at 36

[edit]Built in 1893–1894,[12] by architect Józef Święcicki

This residential building was completed for Robert Aron, a merchant and manufacturer who started in 1889 a business in the production and sale of tar roofing materials.[46] At the time, the address was "Wilhemstrasse 45".[47] Aron's factory employed at the end of the 19th century up to 40 workers and occupied the entire plot between the street and the Brda river.[46] The plant has been active till the start of World War II.[48]

The building has a mansard roof, and initially housed two 7-room apartments.[38]

In 2017, on the left façade of the building has been realized a mural entitled "Kazimierz". Created by Bartosz Bujanowski, it is based on a legend depicting King Casimir the Great meeting a beautiful huntress called Bydgoszcza.[49] This work is a part of an ensemble of more than 20 pieces scattered in Bydgoszcz streets.

-

Side view from Jagiellońska street

-

Main frontage

-

Advertising for Aron's Shop, 1925

-

Mural "Kazimierz"

Gasworks building, at 42

[edit]1859

City gasworks building was built between 1859 and 1860 in Bydgoszcz. In 2003, it became part of the Polska Spółka Gazownictwa (Pomeranian Gas Company).

-

View of Jagiellońska street complex beginning of 20th century

-

Administrative building - View from Jagiellońska street

-

By night

City Slaughterhouse, at 41/47

[edit]Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship heritage list, Nr.601351-Reg.A/505/1-6 (23 April 1998).[7]

1890–1910, by Carl Meyer[50]

The plant was opened on 3 July 1890,[51] designed by architect Carl Meyer.[52] It was located in the former eastern outskirts of the city, near the Gasworks plot. Both companies have been using the 1892 rail track section, which ran along today's Oginski street. The complex comprises four historic buildings. First one (Nr.47) was established in 1893, another in 1897: they comprised administrative and residential buildings, two slaughterhouse halls, a pig house, a firehouse, an intestinal treatment plant, a market place, a butcher's chamber, a water tower, a boiler room, a cold room, a slaughterhouse for sick animals, and a stable.[52] An extension of the complex occurred in 1909 and 1910, including among others, a cash register, rooms for accounting, a room for the vet department, an apartment for the porter and a 6-room apartment for the Slaughterhouse Director.[52] The ensemble was part of the municipal slaughterhouse and meat trade in Bydgoszcz, together with the factory itself.[16] In 1894, a 2 ha plot around the slaughterhouse was established as a trade centre.[4]

In 1920, the company passed into Polish hands, and grew in size: in 1928, company "Bacon Export SA" was established in Gniezno, in 1929-1930, a new bacon processing factory gas been built on site, along Piotrkowski street. The slaughterhouse produced for the local market and also exported abroad.[53] Its best seller to United Kingdom during interwar period was bacon.[54] In 1938, the author J. D. Salinger worked at the slaughterhouse to learn about the meat-importing business.[55]

In 1939, the plant was confiscated and run by the German army, its name was changed to Meat Products Factory "Nawag". The factory company produced bacon, sausages and canned food for the Wehrmacht.[56]

In the years 1945-1949, factories took back their name as city slaughterhouse, subordinated to the control of Warsaw. In the 1960s, the first serious post-war investments for modernization have been realized.[28] After a period of greatest prosperity in 60s and 70s, the slaughterhouse was hit by the economic crisis.[15] In addition, in 1991, Bydgoszcz plants lost their authorization to export to European Union and United States. The need of a construction of a new modernized facility was acute, leading the way to the selling of Jagiellońska street plot in 2006. The product of the bargain provided to build from scratch a new plant at Przemysłowa street (a plot belonging to the former Bydgoszcz Gasworks),[57] but paradoxically, this investment appeared to be hazardous, and financial problems ended with the bankruptcy of the "Bydgoszcz Meat Company" in 2008, after 118 years of operation.[58] In 2009, producers and former supplier established the "Bydgoskie Meat Factory" Company and resumed production in the facility at Przemysłowa street.[59] The same year, the plant became member of the group DROBEX.[59]

One of the most interesting edifice is the former catering and administration building at Nr.47. It is rectangular, brick-laid building, with two-storey, attic and basement. It has a four-storey tower clock in its south-east corner. Frontages are decorated with brick cornices and friezes with arcades. The south elevation displays a terrace with an openwork balustrade. The other three buildings are administrative and residential edifices.[16] When the plot was sold in 2006, the processing factory was demolished to give place to the shopping center Focus Mall. The four historic administrative buildings have been preserved and restored.

-

Slaughterhouse complex on a 1914 Bydgoszcz map

-

View of the main building from Jagiellońska street

-

By night

-

Administrative building - the tower clock

-

Main building, the shopping center "Focus mall" in the background

Focus Mall, at 39/47

[edit]2007-2008

The shopping center "Focus Mall" was opened on 23 April 2008 on the site of the demolished meat processing factory of "Bydgoskie Meat Plant", sold in 2006. It was, at its opening, the biggest mall in Bydgoszcz and in Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, one of the largest in Poland. It houses 150 shops and service points, and a 13 screen multiplex theatre (run by Cinema City Poland). The center has surface of 90 000 m2, including 41 0000 m2 of GLA.[60] It has also a two-level parking for 1 200 cars.

-

Entrance with historic abattoir buildings on the left

-

View of the main car entrance from Jagiellońska street

-

By night

1973-1975

Erected partly on the former area of Bydgoszcz Gasplant, the station covers an area of 5 hectares stretching from Jagiellońska street to the Brda river.[61] On another part of the plot used to stand Weynerowski's sawmill till the German occupation.[62] The recent University Bridge (2013) overhangs the premises.

-

View of PKS building from Jagiellońska street

-

Opposite view

-

Bird eye view from University bridge

Tenements at 51/57

[edit]1900 (Nr.51) 1908 (Nr.53) 1910 (Nr.55) Beginning 20th century (Nr.57)[12]

Early Modern architecture[63]

These townhouses, standing near the intersection with Oginski street, have been built in the first decade of the 20th century. This area was out of the city limits at that time: the suburb was called "Schröttersdorf" and the street "Promenadenstrasse".[64] The first landlords of the ensemble were:

- Fritz Altmann at Promenadenstrasse 1 (51 Jagiellońska)

- Mr Schrödter, a butcher, at Promenadenstrasse 2 (53 Jagiellońska)

- Mr Shring, a secretary in the railway company at Promenadenstrasse 3 (55 Jagiellońska)

- Bernhard Pommerening at Promenadenstrasse 5 (57 Jagiellońska).[64]

The building displays early modernist style, as one can find also at 107 Jagiellońska street or 5 Libelta street.[65]

In 2020, on the occasion of the 25th birthday of the popular cookie "(Wafle) Familijne" (English: Family Wafers) produced by the confectionery factory "Jutrzenka" in Bydgoszcz, a mural was created at the corner with Ogiński streets. The work called Familijne has been designed by Karol Banach.[66] It is a part of an ensemble of more than 20 pieces scattered within Bydgoszcz.

-

Frontages from Jagiellońska street

-

Opposite view from Jagiellońska street

-

Facade at 51

-

Mural Familijne at 51

-

Facade at 57

-

Adorne gate at 53

Tenement at 60

[edit]1910[12]

Early Modern architecture[67]

The plot was initially located outside of Bydgoszcz limits, in the suburban city of Schröttersdorf.[64]

The building displays early modernist style, with some original features such as the rounded wrought iron balconies, the large triangular facade pediment[67] and the overwhelming presence of vertical lines that confers to the edifice a look of a Greek temple. It was renovated in early 2020.[67]

-

Main facade on the street

-

Detail of the balconies

Antoni Jaworski Villa at 61

[edit]1930s by Antoni Jaworski

Jaworski was running a building company co-owned with architect Bronisław Jankowski, using concrete, a new material available at the time. This firm had won prosperous contracts in the sea side city of Gdynia.[68] After the Second World War, the building housed a public library and apartments.[69] After its refurbishing, the villa houses since 2017 the following municipal offices:

- Office for Health and Social Policy (Polish: Zdrowia i Polityki Społecznej Urzędu Miasta Bydgoszczy);[70]

- Integrated Territorial Investments office (Polish: Biuro Zintegrowanych Inwestycji Terytorialnych BTOF).[71]

Jaworski replicated the modern streamline-Art Deco style he used on his works in Gdynia. The front door is adorned with a circular porthole-like window, and the balustrades surrounding the terrace and balconies recall bridge boat railings.[68] Thanks to its large windows, the villa is flooded with a lot of light. Interiors are a real showcase of the skill sets of Jaworski's company, made of high-quality wood and ceramics: the main hall is paneled up to the ceiling with a colored geometric pattern on the floor and a swinging door with crystal-cut panes leads to the stairs equipped with a solid handrail.[69]

-

View from Jagiellonska street

-

Rear view ca 1929

Antoni Weynerowski Villa at 62, corner with Krakowska street

[edit]Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship heritage list, Nr.760205 Reg.A/1588 (10 May 2011).[7]

1907-1908

At the time of its erection, the villa was located out of the city limits, in the suburb of Schröttersdorf, on Promenaden Straße. After 1920 and the re-creation of the Polish state, the expansion of Bydgoszcz subsumed these neighbouring cities; villa's address was then Ulica Promenada 41, then Ulica Promenada 10,[48] when the city gave up the Prussian street numeration. Its first landlord, Antoni Weynerowski, was a successful manager of a large shoe factory, Leo.[72]

In the late 1920s, the landlord was Zefiryn Rzymkowski, a merchant.[73]

The villa, refurbished in 2014,[74] features superb architectural details: vegetal volutes as cartouches, crying figures on top of pilasters and a corner balcony.

-

General view from the street

-

Facade on Krakowska street

-

Detail of the vegetal volutes

-

Detail of the masks flanking the windows

House at 63

[edit]1903[12]

This area was out of the city limits at that time: the suburb was then called Schröttersdorf and the street Promenaden straße.[71]

The building has a pediment which displays the coat of arms of the owner and the date of construction. One can mention the rich woodcarving detail of the entrance gate.

-

Frontage from Jagiellońska street

-

Detail of the pediment

-

Detail of the ornamented gate

Tenement at 64, corner with Krakowska Street

[edit]1930s[12]

Since the end of the 1890s, the tenement at then Promenadenstraße 51, was the property of Marie Fuhr, the widow of a painter.[64] After 1920, It moved to the hands of Edward Lelito, a merchant,[75] also owner of the tenement at today's Nr.1.

This large corner building impresses by its mass. Recently refurbished, one can notice the curved corner pediment, adorned with an ornamented frieze.

-

Elevation on Krakowska street

-

Corner top pediment

Franz Errelis tenement, at 69

[edit]Built in 1902-1903[12] by Józef Święcicki

The building was erected at the request of Franz Errelis, a railway official, according to the last design realizes by Bydgoszcz architect Święcicki. Its features differ totally from the traditional style he used in the past. The building has four floors, with one apartment per level.

-

Frontage from Jagiellońska street, Nr.69 on the left, Nr.71 on the right

-

View from Jagiellońska street, Nr.69 on the left

-

Facade of Nr.69

Bruno Sommerfeld factory, at 92

[edit]Source:[76]

ca 1910

The place was the piano production workshop of Bruno and Ernst Sommerfeld, from 1915 till the end of WII. The factory address was initially Promenaden straße 4.[77] The show room and selling point was located downtown at Śniadecki Street 2. Bruno Sommerfeld company thrived in the 1920s and 1930s, turning its owner into one of the wealthiest Germans citizen in Bydgoszcz. His piano factory was the largest in Poland between 1920 and 1939.[78]

-

Factory facade from the street

-

View of the main building

"Słoneczny Młyn" Hotel, at 96

[edit]1862[79]

The first reference of the mill dates back to 1862, but studies show that a mill facility was standing there earlier.[80] The building was erected by entrepreneurs Louis Wolfen and Meyer Fließ,[50] initially as a small steam mill with a capacity of approximately 1 ton per day. Its economic importance was then negligible. However, the location of the facility made it very convenient for transportation of grain and flour by waterways, via Brda river and the Bydgoszcz Canal. In 1892, the mill was bought by L. Berwald, and in 1899, it was in the hand of Willi and Moritz Baerwald.[52] They carried out a thorough upgrading and extended the building to its limits for the time: equipment comprised, among others, a new steam engine and a narrow-gauge railway to a bridge over the Brda river, where transportation barges were standing. "Baerwald mill" daily production, from 15 to 20 tons in the late 19th century, rose up to 30 tons in the early 20th century, with a workforce of 20 to 25 people. In 1916 was built the high five-storey granary tower, today's dominant architectural item of the complex.[52]

Bronisław Kentzer, who gave his name to the building, managed the mill from 1938 to 1939. Under his leadership, the production peaked up to 50 tons per day. In autumn 1939, he was murdered by the Nazis, probably in Fordon's Valley of Death. In 1940 the facility was taken over by German authorities. After World War II, the building was briefly in the hands of a Cooperative, "Społem" ("Together"), then led by Jan Kentzer. After 1948's nationalizations, the mill was managed by the State Cereal Plant in Bydgoszcz, using it to produce flour and other cereal products. Many significant structural changes occurred afterwards: in 1961, steam engine was replaced for an electric one, and in the 1970s, offices, workshops, sheds and garages were built on the site of the demolished boiler room . At the end of the 1990s, the mill reached a record production of 100 tons of grain a day. At the same period, the company was transformed into a Joint-stock company. This did not save the firm and, in 2003, the mill complex stopped production, the buildings being put up for sale.

The property was bought by Barbara Komorowska, co-owner of the "Bakoma" company. From 2007 to 2009, the edifice was entirely refurbished and turned into a stylish four-star hotel under the name Sunny Mill (Polish: Słoneczny Młyn). The old granaries were demolished and other buildings were restored and integrated into a single complex. On the river side stands a cafe, along the river promenade, where the Bydgoszcz Water Tram stops. "Słoneczny Młyn" offers 96 rooms, 5 meeting rooms and a spa area. The suite in the tower offers panoramic views on Bydgoszcz. The decor refers to characteristic details of the early 20th century: Art Nouveau and Art deco. Individual floors of the hotel reflect the atmosphere of the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn, winter.[81]

The main part of the mill building dates back to 1916, but the ensemble has experienced an important amount of transformations. It displays the architectural characteristics of early industrial buildings.

-

Kentzer's mill ca 1870

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

Riverside elevation

-

By night by the river

-

By night, river facade

-

By night, from Jagiellońska street

House at 107

[edit]ca 1900

Early Modern architecture[63]

The building is one of the last old house on Jagiellońska. At the time of its erection, the plot was located out of Bydgoszcz city limits, in the village of "Schröttersdorf", and the street bore the name of "Promenadenstrasse" or "Chausseestrasse". The edifice early modernist style, as one can find also at Jagiellońska street Nr.51/57 or 5 Libelta street[65]

-

View from Jagiellońska street

-

Frontage on Pestalozziego street

Pasamon complex, at 117

[edit]1924,[82] by Jan Kossowski

The firm Pasamon has been producing haberdashery woven ribbons and tapes since 1924.

The complex was realized in the late 1930s by Bydgoszcz architect Jan Kossowski: he designed the workshop area, but also the villa of the director.

-

Pasamon factory, 1938

-

Pasamon advertising, 1929

-

Entry gate of the plant on the street

-

View of 1930s factory buildings

References

[edit]- ^ Zyglewski, Zbigniew (1995). Dwa najstarsze plany Bydgoszczy z roku 1657. Bydgoszcz: Kronika Bydgoska XVI.

- ^ Licznerski, Alfons (1965). Rozwój terytorialny Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: Kronika Bydgoska II.

- ^ Michalski, Stanisław (1988). Bydgoszcz wczoraj i dziś. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe Warsaw-Poznań.

- ^ a b c Czachorowski, Antoni (1997). Atlas historyczny miast polskich. Tom II Kujawy. Zeszyt I Bydgoszcz. Toruń: Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika.

- ^ Rasmus, Hugo (1996). Od tramwaju konnego do elektrycznego. Bydgoszcz: Kronika Bydgoska XVII.

- ^ Boguta, Tadeusz (1964). Rozwój i aktualna problematyka komunikacji miejskiej w Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: Kronika Bydgoska II.

- ^ a b c d e POWIATOWY PROGRAM OPIEKI NAD ZABYTKAMI POWIATU BYDGOSKIEGO NA LATA 2013-2016. Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-pomorskie. 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Piękne, znane i zaniedbane". bydgoski.pl. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Savoy - We run the space". savoy.pl. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ zbyszekf60 (2007). "Pamięci Stanisława Niewiteckiego". polskaniezwykla.pl. polskaniezwykla. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Załącznik do uchwały Nr XXXIV/601/13. Sejmiku Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego. 20 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jasiakiewicz, Roman (24 April 2013). Uchwala NR XLI/875/13. Bydgoszcz: Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 86–87.

- ^ Janiszewska-Mincer, Barbara (1998). Bydgoszcz jako stolica regencji w latach 1815–1914. Bydgoszcz jako ośrodek administracyjny na przestrzeni wieków. Bydgoszcz: Prace Komisji Historii BTN t. XVI.

- ^ a b c "Urząd od 1836 roku". bydgoszcz.uw.gov.pl. Kujawsko-Pomorski Urząd Wojewódzki w Bydgoszczy. 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Umiński, Janusz (1996). Bydgoszcz. Przewodnik. Bydgoszcz: Regionalny Oddział PTTK "Szlak Brdy". p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e f g Parucka, Krystyna (2008). Zabytki Bydgoszczy – minikatalog. Bydgoszcz: "Tifen" Krystyna Parucka.

- ^ Kaja, Renata (1995). Bydgoskie pomniki przyrody. Bydgoszcz: Instytut Wydawniczy "Świadectwo". ISBN 83-85860-32-0.

- ^ a b c d Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria (1999). Bydgoskie realizacje Heinricha Seelinga - Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 4. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Derkowska-Kostkowska, Bogna (2007). Miejscy radcy budowlani w Bydgoszczy w latach 1871-1912. MATERIAŁY DO DZIEJOW KULTURY I SZTUKI BYDGOSZCZY I REGIONU Z.12. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia dokumentacji i popularyzacji zabytków wojewódzkiego ośrodka kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 11–22.

- ^ Biskup, Marian. Historia Bydgoszczy. Tom I. Do roku 1920. Bydgoszcz: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe Warsaw-Poznań 1991. p. 588. ISBN 83-01-06666-0.

- ^ Agnieszka Kołosowska, Leszek Woźniak (2014). Bydgoszcz Guide. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Tekst. p. 148. ISBN 978-83-917786-7-8.

- ^ a b Wisocka, Agnieszka (2003). Działalność architektoniczna Jana Kossowskiego w Bydgoszczy w latach 1923-1939. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia dokumentacji i popularyzacji zabytków wojewódzkiego ośrodka kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 79–98.

- ^ "City Hotel". city-hotel.pl. City Hotel. 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Janina-Janikowska, Danuta Beata (2003). Rola bydgoskiego szpitala wojskowego w systemie wojskowych zakładów leczniczych Okręgu Generalnego "Pomorze" i Okręgu Korpusu VIII. Bydgoszcz: Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 8.

- ^ Mackiewicz, Zygmunt (2004). Historia szkolnictwa wyższego w Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. p. 18. ISBN 83-917322-7-4.

- ^ Derenda, Jerzy (2006). Piękna stara Bydgoszcz – tom I z serii Bydgoszcz miasto na Kujawach. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Rogalski, Bogumił (1992). Przegląd współczesnej architektury publicznej i urbanistyki Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: Kronika Bydgoska XIV.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Michalski, Stanisław (1988). Bydgoszcz wczoraj i dziś 1945-1980. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe Warsaw-Poznań. ISBN 978-83-01-05465-6.

- ^ a b c d Woźniak, Wojciech (1974). Pałac naprawdę młodzieży. Bydgoszcz: Kronika Bydgoska.

- ^ Pluta, Joanna (28 January 2015). "Pałac Młodzieży w Bydgoszczy doczeka się remontu. A kiedy?". pomorska.pl. Gazeta Pomorska. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Fiałkowski, Szymon (4 September 2019). "Pałac Młodzieży jak nowy. Zakończyły się prace remontowe". metropoliabydgoska.pl. Enjoy!Media. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz Musical Impressions News". Bydgoszcz Musical Impressions. 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Pałac Młodzieży w Bydgoszczy". palac.bydgoszcz.pl. Pałac Młodzieży w Bydgoszczy. 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Kaja, Renata (1995). Bydgoskie pomniki przyrody. Bydgoszcz: Instytut Wydawniczy "Świadectwo". ISBN 83-85860-32-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Kuczma, Rajmund (1995). Zieleń w dawnej Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: Instytut Wydawniczy "Świadectwo".

- ^ Gliwiński, Eugeniusz (1996). Kontrowersje wokół nazwy parku im. W. Witosa. Bydgoszcz: Kalendarz Bydgoski.

- ^ "ZASKAKUJĄCE WYNIKI PRAC ARCHEOLOGICZNYCH". bydgoszczwbudowie.pl. Bydgoszcz w Budowie. 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ a b Materiały do Dziejów Kultury i Sztuki Bydgoszczy i Regionu. zeszyt 6., Derkowska-Kostkowska Bogna (2001). Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy (ed.). Józef Święcicki – szkic biografii bydgoskiego budowniczego, Materiały do Dziejów Kultury i Sztuki Bydgoszczy i Regionu, zeszyt 6 (in Polish). p. 45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1897. p. 64.

- ^ Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1910. p. 394.

- ^ a b Błażej Bembnista (7 November 2020). "Historie bydgoskich budynków #1: Kamienica przy Jagiellońskiej 30". metropoliabydgoska.pl. Enjoy Media. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Restauracja Orientalna Rong Vang". rongvang.com.pl. SequenceStudio. 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ JASKOWIAK, JERZY (1976). Śródmieście pólmilionowej Bydgoszczy Wejrzenie w przyszłość. Bydgoszcz: Kalendarz Bydgoski. p. 9.

- ^ key (16 February 2013). "Budynek NOT był szczytem techniki". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. bydgoszcz wyborcza. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Umiński, Janusz (1996). Bydgoszcz. Przewodnik. Bydgoszcz: Regionalny Oddział PTTK "Szlak Brdy".

- ^ a b "Architektura bydgoskich fabryk na winietach papierów firmowych". kpck.pl. Kujawsko-Pomorskie Centrum Kultury w Bydgoszczy. 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1895. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1895. p. 60.

- ^ a b "Alfabetyczny spis mieszkańców miasta Bydgoszczy". Książka Adresowa Miasta Bydgoszczy : na rok 1933. Bydgoszcz. 1933. pp. 5, 70.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ""Kazimierz" Mural". visitbydgoszcz.pl. visitbydgoszcz. 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ a b Agnieszka Kołosowska, Leszek Woźniak (2014). Bydgoszcz Guide. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Tekst. p. 121. ISBN 978-83-917786-7-8.

- ^ wal (3 July 2013). "Miejska rzeźnia wyglądała niczym zamek". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. bydgoszcz wyborcza. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Koronowskie Stowarzyszenie Rozwoju Turystyki „Szczesliwa Dolina” (30 September 2013). Raport z inwentaryzacji i waloryzacji dziedzictwa przemyslowego Bydgoszczy na cele szlaku kulturowego. Bydgoszcz: SHIFT-X project. p. 43.

- ^ Biskup, Marian (1999). Historia Bydgoszczy. Tom II. Część pierwsza 1920-1939. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. p. 77. ISBN 83-901329-0-7.

- ^ "Bydgoskie Zakłady Mięsne". bydgoskiezm.pl. Bydgoskie Zakłady Mięsne. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ Salinger, Margaret (2000). Dream Catcher: A Memoir. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 0-671-04281-5.

- ^ Biskup, Marian (2004). Historia Bydgoszczy. Tom II. Część druga 1939-1945. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. p. 243. ISBN 83-921454-0-2.

- ^ Derenda, Jerzy (1999). Zakady Mięsne w Bydgoszczy. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: TOWARZYSTWO MIŁOŚNIKÓW MIASTA BYDGOSZCZY.

- ^ Myga, Maciej (15 July 2008). ""Byd-Meat" i "Kujawy" uda się uratować?". pomorska.pl. Gazeta Pomorska. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b Myga, Maciej (31 March 2009). "Bydgoskie Zakłady Mięsne wracają na rynek". pomorska.pl. Gazeta Pomorska. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Cichla, Aneta (6 October 2014). "Focus Mall Bydgoszcz zmienia właściciela". eurobuildcee.com. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Umiński, Janusz (1996). Bydgoszcz. Przewodnik. Bydgoszcz: Regionalny Oddział PTTK "Szlak Brdy".

- ^ Błażejewski, Krzysztof (2 November 2006). "Niemcy zabrali, PRL przywłaszczyła". nowosci.com.pl. Polska Press Sp. z o. o. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b bj. "Jest moda na modernizm. Oto bydgoskie budynki w tym stylu". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. bydgoszcz.wyborcza. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1911 auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1911. p. 219.

- ^ a b bj (29 September 2015). "Jest moda na modernizm. Oto bydgoskie budynki w tym stylu". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. bydgoszcz.wyborcza. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ ""FAMILIJNE" (FAMILY) WAFERS IN BYDGOSZCZ". visitbydgoszcz.pl. visitbydgoszcz. 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ a b c dss (28 January 2020). "Jest moda na modernizm. Oto bydgoskie budynki w tym stylu". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ a b Wysocka, Agnieszka (10 January 2016). "Wysocka odkrywa Bydgoszcz. Willa na Promenadzie". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ a b grzechotnik (2018). "Architektura dla opornych #3 - Willa na promenadzie w Bydgoszczy". steemit.com. steemit. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Nowa siedziba Biura ds. Zdrowia i Polityki Społecznej". bydgoszcz.pl. Miasto Bydgoszcz. 12 September 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ a b UAF (27 October 2020). "Estetyczne zmiany na ul. Jagiellońskiej". bydgoszcz.pl. Miasto Bydgoszcz. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Andrzejewski, Roman (2008). "LEO" od Weynerowskich. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ "Names". Adresy Miasta Bydgoszczy na rok 1926. Bydgoszcz: Leon Posłuszny. 1926. p. 305.

- ^ Lewińska, Aleksandra (23 February 2015). "Jagiellońska 62". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Właściciele domów". Adresy Miasta Bydgoszczy na rok 1922. Bydgoszcz: Leon Posłuszny. 1922. p. 355.

- ^ "Industrial heritage of Bydgoszcz". visitbydgoszcz.pl. Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji. 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Umiński, Janusz (2010). Fabryka pianin i fortepianów. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ "INSTYTUCJE Fabryka pianin i fortepianów B. Sommerfelda". Akademia Muzyczna w Bydgoszczy Muzyczne. Akademia Muzyczna w Bydgoszczy Muzyczne Archiwum Pomorza i Kujaw. 2013. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Kulesza, Maciej (4 March 2013). "Od firmy do hotelu. Historia młyna Kentzera". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. bydgoszcz wyborcza. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Jarocińska, Anna (2007). Stare młyny. Bydgoszcz: Kalendarz Bydgoski.

- ^ "Hotel Słoneczny Młyn". sloneczny.eu. Hotel Słoneczny Młyn. 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Fabryka pasmanterii, taśm i pasów "Pasamon"". visitbydgoszcz.pl. Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji. 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

External links

[edit]- Drukarnia shopping mall (in Polish)

- Savoy club in Bydgoszcz (in Polish)

- Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship office in Bydgoszcz

- Main Post office of Bydgoszcz (in Polish)

- Nicolaus Copernicus University Ludwik Rydygier Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz

- City Hotel at 6 (in Polish)

- Youth Palace (in Polish)

- Focus Mall shopping center

- Słoneczny Młyn Hotel

- Pasamon company (in Polish)

Bibliography

[edit]- Umiński, Janusz (1996). Bydgoszcz. Przewodnik (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Regionalny Oddział PTTK "Szlak Brdy".

- Winter, Piotr (1997). Dawne bydgoskie budynki pocztowe i z pocztą związane. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu, z. 2 (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 17–43.

- Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria (1999). Bydgoskie realizacje Heinricha Seelinga. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu, z. 4 (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 15–38.

- Parucka, Krystyna (2008). Zabytki Bydgoszczy: minikatalog (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: TIFEN" Krystyna Parucka. ISBN 9788392719106.

- Bręczewska-Kulesza Maria, Wysocka Agnieszka (2007). Historia i architektura gmachu NBP w Bydgoszczy. Kalendarz Bydgoski (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- Garbaczewski, Witold (2004). Narodowy Bank Polski Oddział Okręgowy w Bydgoszczy – historia i współczesność. Kalendarz Bydgoski (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- Michalski, Stanisław (1988). Bydgoszcz wczoraj i dziś 1945-1980 (in Polish). Warsaw-Poznań: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. ISBN 9788301054656.

- Pruss Zdzisław, Weber Alicja, Kuczma Rajmund (2004). Bydgoski leksykon muzyczny (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-Pomorskie Towarzystwo Kulturalne.

- Praca zbiorowa (1996). Bydgoska Gospodarka Komunalna. Bydgoszcz. ISBN 8385860371.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kaja Renata, Kuczma Rajmund (1995). Zieleń w dawnej Bydgoszczy (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Instytut Wydawniczy "Świadectwo". ISBN 8385860320.

- Fred, Jerzy (1981). Z tej mąki jemy chleb. Kalendarz Bydgoski (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 21–26.

- Derkowska-Kostkowska, Bogna (1998). Młyn na Szreterach. Kalendarz Bydgoski (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 245–248.

- Jarocińska, Anna (2007). Stare młyny. Kalendarz Bydgoski (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.