Długa Street, Bydgoszcz

| Bydgoszcz | |

|---|---|

View of the street | |

Location of Długa Street in Bydgoszcz | |

| Native name | Ulica Długa w Bydgoszczy (Polish) |

| Part of | Bydgoszcz Old town district |

| Namesake | Long ("Długa") street |

| Owner | City of Bydgoszcz |

| Length | 650 m (2,130 ft) |

| Location | Bydgoszcz, |

Długa Street is the longest street of Old Town district in Bydgoszcz and the most important historically. It stands next to Gdańska Street and Dworcowa Street as one of the most important avenues of downtown Bydgoszcz.[1]

Location

[edit]The street is located in the heart of the Old Town. It extends approximately on an east–west axis, from the Zbożowy Rynek ("grain market") near southern tip of Bernardyńska Street to Wool Market square (Polish: Wełniany Rynek). It is approximately 650 metres (2,130 ft) long.

Naming

[edit]The street in its long history has borne the following names:[2]

- 16th century – first half of the 18th century, "Platea Longa"

- 1774–1800, Lange Gasse

- 1800–1816, Langestraße

- 1840–1920, Friedrichstraße

- 1872–1920, for the eastern part, Kornmarktstraße

- 1920–1939, Długa street

- 1920–1931, for the former Kornmarktstraße section, Szpitalna

- 1939–1945, Friedrichstraße

- From 1945, Długa street.

History

[edit]Period before the First Partition

[edit]Długa street was laid out in the middle of the 14th century, at the time of the creation of the chartered city of Bydgoszcz. Until the beginning of the 19th century, it was the longest and the busiest street in the city, connecting two city gates : the Kujawska Gate to the east and the Poznan Gate to the west.[3] The street was flanked by two parallel running axis: Pod Blankami street on the south and Zaułek street on the north. Both streets were designed to carry supplies for horses in local stables.[4] The first residential buildings in Długa Street were made of wood, according to the wattle and daub technique. Brick houses appeared no earlier than 15th century.[4] The first written mention of Długa Street dates back to the middle of 16th: in the years 1559–1561, it was known as "Longa platea" or "Longa platea Civili" (Latin for "long civilian street"). In these sources, the numerous references are made to brick buildings, homes, dwellings, empty squares and breweries located in the street. Preserved entries from the 16th to the 17th century bear witness of a lively environment. Around 1619–1622, mention is made of 18 brick houses standing on the street. The owner of one of them was a city bailiff. Habitations along the street were housing many craftsmen, such as shoemakers, tailors, masons, locksmiths, as well as representatives of the nobility.

Archaeological studies in the Old Town of Bydgoszcz could not determine exactly where are located today the old basements from the 16th and 17th centuries,[4] most of them dating back to the end of the 18th century, and the oldest being from 1623. However, 2008 archaeological excavations have allowed identification of 16th-century brick remains at Długa 52, and basement from the end of the 17th century at 9 Długa. Many of the cellars searched have been built between the 18th and the 19th centuries[4]

In the first half of the 16th century, a wooden city water supply for the citizens have been built in Długa street. Archaeological discoveries revealed the entire length of the street timber water pipe extending 0.6 to 1.5 m deep.[5]

One of the most interesting discoveries associated with the history of Długa Street happened in March 2004. In the process of the demolition of the building at Nr.9, a decorative wooden ceiling from 1730 has been exposed. It bore the initials of the landlord, "Maciej Rychlicki", councilor and bailiff of the city: ceiling beams are now exposed in the restaurant Browar Pub now occupying the premises.[4]

The oldest buildings front of Długa Street have been destroyed, mainly in the end of the 18th century and the turn of the 19th century.[4]

Period of the Prussian occupation

[edit]The passage of Bydgoszcz under the authority of Kingdom of Prussia in 1772 marked a new step in the history of Długa Street, especially in its architectural appearance. According to a survey for a map of the Bromberg realized in 1774, 45 of the 95 properties in the street renamed Friedrichstrasse were at that time newly built up.

Until 1820, the street remained one of the only city's main thoroughfares with Gdańska Street and Dworcowa Street. At the end of the 18th century, there were inns in Długa street, Hotel de Pologne and Hotel de Varsovie, both multi-storey buildings covered sloping roofs, built in the second half of the 18th century.[6]

In the 19th century, the following hotels were located in Friedrichstrasse:[6]

- "Rio's hotel" (then from 1932 Hotel Rio) at 31 Długa – 53 Friedrichstrasse, built in the late 18th century. Closed in 1939;

- "Hotel Garni" at 22 Długa – 29 E Friedrichstrasse, built in the early 19th century;

- "Hotel Lengning" at 37 Długa – 56 Friedrichstrasse, opened in 1882. Now Hotel Ratuszowy;

- "Hotel de Rome", at the junction of Długa street with Podwale Street and Kościelecki Square, built in the early 19th century. Closed in 1869.

Between 1815 and 1840, Prussian authorities started to demolish a number of derelict urban buildings, most of them from the 16th century. Among others, this operation removed:

- the Old Town Hall (now under the Main Square);

- St. Mary's Church (Carmelites), St. Stanislaus Church, Old St. Trinity Church and Old Holy Cross Church;

- fragments of the city walls;

- Kujawska Gate (1817) and Poznan Gate (1828) which were closing each end of Długa street.

Since the middle of the 19th century, Jews have settled in the middle section of the Street (from Jan Kazimierz street to Stefan Batory street). They had their shops and most of their habitation houses.[7] In 1834, a synagogue was built in Pod Blankami street, as well as a Jewish school building. In 1882, the old synagogue was extended to accommodate the rapid growing community. Alfred Cohn, of Jewish origin, who lived 19 years in a house at the corner with Jan Kazimierz wrote a book about his memories of the period around the turn of the 20th century in this street. This book accurately depicts shops and premises of the small Jewish quarter, in Długa street in the early 20th century, such as:[7]

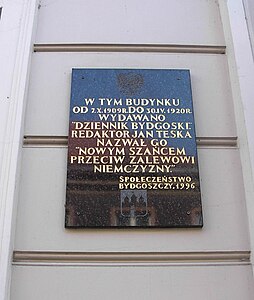

- the Seat of the local Polish newspaper "Dziennik Bydgoski" at 52 from 1908;

- Coffee shop Nachtigall, later Berend (till 1945);

- the seat of the Masonic lodge;

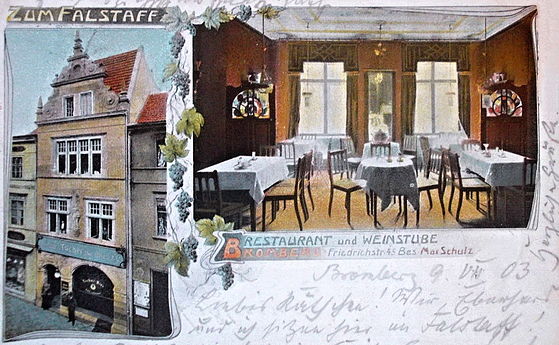

- Restaurant "Falstaf II" (1907);[8]

- Hotel Rio's;

- Hotel Lengning;

- Police station and seat of the Mayor of Bydgoszcz (Nr.41).

Since 1888, tram network -initially horsecars and from 1896 electrical powered- have run in the area.[7]

Between World War I and World War II

[edit]As Bydgoszcz returned to motherland's territory in 1920, the street took back its original Polish name "Długa" and in 1931, the renumbering of the street was carried out. It was also extended towards the east, to include the old Hospital street were has been standing St. Stanislaus Church and its hospice from 1583 to 1817.

The address book of Bydgoszcz registered in 1934 in Długa street 21 stores (e.g. good products, haberdashery, food, etc.). In addition, there were here 12 tailors, 11 warehouses, 7 shops for menswear, 6 furniture stores, 4 offices writing applications, 4 restaurants, 3 stores for stationery paper and a butcher.[9]

Period after 1945

[edit]By the mid-20th century, the street had a successful mercantile and commercial nature, mainly with craft workshops and gastronomy. In 1945, after the reconstruction of the bridge over the Brda river connecting the old town with Theatre square, tram service resumed in Długa street. In 1969, the streetcar traffic was stopped in the western part of the street, and in 1973, the rest of the network in the Old Town has been disbanded, giving priority to the pedestrian zone. At the same time (1976–1982), restoration started for some the houses of Długa.

In the 1990s, after heavy works between Wełniany Rynek in Bydgoszcz and Jan Kazimierz street, the environment have been transformed into a promenade, closed to traffic. Modernization works occurred also in 2005 between Jan Kazimierz Street and Podwale street. In 2007 has been unveiled the "Autographs alley", displaying signature plaques of famous personalities embedded in the street pavement. In June 2008, at the intersection with Jan Kazimierz Street has been placed a historic tram car, acting as a seasonal Tourist Information Centre[10] and reminding of the gone streetcar activity in the area.

Since 2005, and the completion of Długa street renovation, has been initiated the "Feast of Długa street" (Polish: Święto ulicy Długiej),[11] taking place in June each year. In the following years, other commercial events happened in the street, like the "Długa street Fair", the "Easter Fair" or the "Christmas Market". In 2009, has been achieved the reconstruction of the western end of the street, the "Wool Market" (Polish: Wełniany Rynek), with the setting of a monument to Leon Barciszewski, Mayor of Bydgoszcz from 1932 to 1939.

Architecture

[edit]Długa Street in Bydgoszcz comprises almost entirely built stylish houses. This fact reflects its importance as a representative, a trade thoroughfare in the Old Town. Most frontages have been built in 18th and 19th century, in different architectural styles: neoclassicism, eclecticism and Italian or Northern European Neo-Renaissance. Many frontages are influenced by ancient architecture.[12] Facade in Długa street mark an architectural difference in comparison to styles one can notice in the other parts of Bydgoszcz such as

- Neo-Baroque and Historicism, characteristics of downtown buildings (i.e. Gdańska Street, Dworcowa Street, Cieszkowski Street, Adam Mickiewicz Alley in Bydgoszcz),

- Art Nouveau,

- Modernism.[13]

Older buildings have generally a rough shape, a limited decoration with a mixing of styles ( eclecticism), characteristic of the second half of the 19th century. Facades are generally horizontally by cornices, especially on the top of buildings. They are often decorated with classical ornaments such as: astragals, cymatia, meanders, palmette friezes and triglyphs. Vertical façade articulations are realized through columns, pillars and pilasters. Some houses are adorned with pediments including tondi or allegorical statues.[12] Columns and pilasters also appear in window frames and door openings, usually topped by a frontage and more rarely with decorated friezes.[12]

Edifices constructed or rebuilt in the 1870s have richer decorations, mainly with a Neo-Renaissance style. Classical architecture decorative elements have been combined with elements of Renaissance origin and bossage or railings. Among such houses, those at Nr.32 and 35 stand out.[14] Neo-Renaissance style has been popular in these houses from the end of the 19th, as it was at the time in the German Empire, France and throughout northern Europe. Facades display red or yellow bricks, contrasting with bright, plastered detail, stone-like decoration. Compositions are dominated by symmetry and horizontal divisions. Roofs are generally mansarded, with peaks embellished with volutes, completed by pinnacles or figures: it is the case in houses at Nr.12, 24, 34 & 46.[14]

Many houses on Długa Street were also rebuilt in the second half of the 20th century: some were even dismantled before being reconstructed again. Between 1976 and 1982, houses from Nr.13 to 21 have undergone such process,[1] another stage of thorough restoration has occurred after 2000. In 2014, Bydgoszcz's Mayor has begun to issue administrative orders to landlords compelling them to carry out renovation works: such was the instance for houses at Nr.10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 58.

Many properties had been recognized as historical monuments. In 2015, in the heritage list of Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship 12 sites located on Długa Street were listed.[15]

Most significant buildings in the street include:

- Tenement at 52, seat of the Provincial Administrative Court,

- Tenement at 41, seat of the Provincial and Municipal Public Library,

- Hotel Ratsuszowy ("City Hall Hotel") at 37.

Revitalisation

[edit]Over the 1990s, the street experienced difficulties to attract and develop of a network of shops, with customers' tendency to leave downtown district. The association "Bydgoszcz Old Town" (Bydgoska Starówka), located at 32, initiated the project of revitalisation of Długa street: it organized events popularizing the area, and thus improved the image of Długa street. Officials helped for the renovation of the houses, for fairs organization and the development of a network of galleries and cafes. The pavement after renovation now integrates old gates outlines, Kujawska's and Poznan's.[16] In recent years, the street received an increasing number of tourists, also attracted by the Old Town and Mill Island's area.

"Autographs avenue"

[edit]

Bydgoszcz Autographs alley is a collection of relief signature embedded into the pavement of Długa street, between the streets Jan Kazimierz and Stefan Batory streets. These granite plaques display Polish meritorious men and women. This theme avenue is the result of a competition run in 2007, aiming at creating new attractions in Bydgoszcz. The competition gathered 123 proposals, the City Hall council settled the contest in November 2007: the author of the winning idea of Bydgoszcz's Autographs alley was Halina Piechocka-Lipka, director of the cultural department of Bydgoszcz.[17] Local artist Michał Kubiak designed the plaques, nominated names are chosen by a committee comprising among others municipality members and university officials.

The first autograph has been unveiled on December 6, 2007, and the following have traditionally respected the same date, the day of Saint Nicholas, patron of the city. Most famous people's signatures are:

- Rafał Blechacz, pianist (2007),

- Zbigniew Boniek, football player (2007),

- Jerzy Hoffman, film director (2077),

- Adam Sowa, founder of the Sowa patisserie company (2007),

- Irena Szewińska, sprinter (2007),

- Tomasz Gollob, speedway biker (2008),

- Kazimierz Karabasz, documentary filmmaker (2008),

- Katarzyna Popowa-Zydroń, pianist (2008)

- Lech Wałęsa, Statesman and politician (2008),

- Irena Santor, singer (2009),

- Radosław Sikorski, politician and journalist (2009),

- Leonard Pietraszak, actor (2012),

- Robert Sycz, rower (2012).

Main places and buildings

[edit]House at 1

[edit]End of the 19th century[18]

Initial address was Wollmarkt 16.[19] The main elevation has been renovated in 2014.

-

Main facade before restoration

-

Facade after restoration

-

Detail of window and pediment

House at 2

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.760204, Reg. A/1595 (September 8, 2011)[15]

1892[15]

The building has been housing a bakery for more than 80 years. Actual baker, Józef Erdmann, still owns in his shop an oven from World War I.[20]

-

General view from Długa street

-

Main elevation

-

Facade

-

Ornamented window

-

Detail of the gate portal

-

The 80 years old bakery at 2

House at 3

[edit]Second half of the 19th century,[18] by Anton Hoffmann[21]

The main elevation has been renovated in 2014/2015. In 1900, a hardware store ("Victoria droguerie") was standing there, at "Wollmarkt 17".[22]

-

Main facade before renovation

-

Facade after renovation

House at 4

[edit]1775

This tenement house is located on the corner with Pod Blankami street. In the basement are gothic vaults from the 15th century. The Neo-Baroque facade has lost its features during the restoration led by Stefan Klajbor in 1967–1969. Bydgoszcz architect Anton Hoffmann lived there with his family in 1864. The place housed for a long time the "Bydgoszcz Scientific Society" (Polish: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe).[1]

-

Main facade

House at 5

[edit]19th century

Neoclassical architecture, fragments of old motifs

The tenement has been rebuilt in 1925–1930.[18]

-

Facade before renovation

-

Main facade today

-

Ornaments on top of the facade

House at 6

[edit]Middle of the 19th century[18]

Neoclassical architecture, elements of Eclecticism

Located at Friedrich Straße 37 during the Prussian times, it was then owned by the Jacobi Brothers.[23]

-

Main elevation

-

Details of the facade

-

Cartouches with owner's initials

House at 9

[edit]Middle of the 19th century[18]

The basement of the house dates back to the 17th century. In the middle of the 18th century, the landlord was a city councilor, bailiff and treasurer, Maciej Rychlicki. His son Wojciech rebuilt down to the ground the tenement in 1784–1802. In 2004, during a demolition operation has been discovered a profiled ceiling from 1730: it is fragmentedly exposed in the actual renovated shop, the "Browar Pub".[24]

-

Main elevation

House at 10

[edit]18th-19th century[18]

It housed the winery "Goerdel" from 1892 to World War I[25] at 35 Friedrich Strasse.

Jan Jakub Goerdel, arrived in Bydgoszcz from Wielkopolska and established there the firm "J. J. Goedel" on November 11, 1811.[26] The house has stylish, beautiful, very long and deep cellars where the wine has been aged at the end of the 19th century. The side of the property giving onto Pod Blankami street housed a factory producing flavored vodka, five-star cognac and liqueurs[26]

-

Advertising for Goerdel Firm ca 1936

-

Main facade

-

Detail of one gate

-

Detail of the other gate

House at 11

[edit]19th century[27]

The house was inhabited during almost a century by the Lebenheim family (Amalie, Jacob, Wilhem) who worked in the leather business,[27][28] when the address was "Friedrich Straße 43". This tenement is at the intersection with Przyrzecze street.

-

View from Długa street

House at 12

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.601280, Reg. A/1114 (October 8, 1993)[29]

1866–1872[18]

Northern Europe Neo-Renaissance

The house has been rebuilt in 1879 following a design by Carl Stampehl:[14] the roof has an attic topped by a pinnacle.[14] In Bydgoszcz, Carl Stampehl also designed, among others :

- The House at 24 in the same street in 1885,

- Emil Bernhardt tenement at 16 Gdańska Street in 1884,

- Tenement at Gdanska street 22 in 1875,

- Villa Carl Blumwe at 53 Nakielska street in 1893.

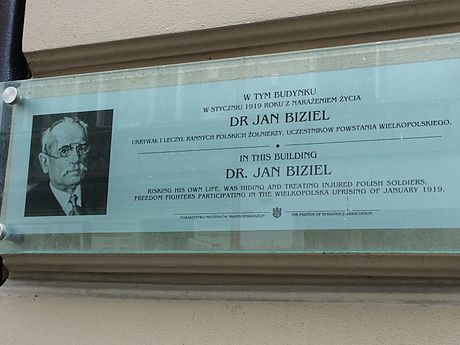

The house has been owned since 1916 by the family Stryszyk. During the Greater Poland Uprising, premises served as infirmary for wounded insurgents, with the heroic help of Dr. Jan Biziel and thanks to the kindness of Stanislaw Stryszyk.[30] Another member of the Stryszyk family, Alojzy Stryszyk aka "Ali", merchant and sports activist,[31] lived there. He was murdered by the Germans on May 26, 1942. Both men, Jan Biziel and Alojzy Stryszyk, are honored by plaques at 12.

-

Facade on Długa street

-

Detail of the attic

-

Ornamented gate

-

Second ornamented gate

-

Plaque in memoriam of Jan Biziel

Museum of Soap and History of Dirt at 13

[edit]1850-1900[18]

The elevation, renovated in 2014, exposes lean neo-classical features.

Since 2012, the building harbours the Bydgoszcz Museum of Soap and History of Dirt (Polish: Muzeum Mydła i Historii Brudu in Bydgoszcz), which premises extend to neighbouring houses at N.15 and 17.

-

Facade from the street

-

Entrance of the museum

House at 15

[edit]1775–1783[18]

Northern Europe Neo-Renaissance

The facade, renovated in 2014, displays a sculpture of a soldier or a hunter with his sword, surrounded by a winegrape vegetation. At the tip of the elevation, the gable is topped by stylized pinnacles. From 1903 till World War I, a restaurant, "Zum Falstaff", owned by Max Schulz was located here,[32] at "Friedrich strasse 45".

Today, the ground floor houses the Museum of Soap and History of Dirt.[33]

-

Main elevation

-

Detail of the sculpture on the facade

-

Detail of facade motif

-

Gate detail

-

1903 advertising for the restaurant "Zum Falstaff"

House at 16

[edit]Second half of the 19th century[18]

Neoclassical architecture, elements of Eclecticism

At the end of the 19th century, this tenement at then Friederich Straße 32 was the property of the Conitzer brothers,[34] who established in 1911 the department store Jedynak at Gdańska Street 15.

Almost no architectural motifs survived today.

-

Main facade

House at 17

[edit]Middle of the 19th century[18]

Northern Europe Neo-Renaissance

The main elevation has been renovated in 2015. At the top of the building are allegorical reliefs depicting woman figures in a sitting position symbolizing Literature and Painting.

Today, the ground floor houses the Museum of Soap and History of Dirt.[33]

-

Main elevation

-

Colored adornements on the facade

-

Allegories on the gable

-

Left elevation renovated

House at 18

[edit]Middle of the 19th century[18]

The house, located at Friedrich Straße 31 during Prussian period, was the property of Wilhelm Schulße Jr., who had been running a hat workshop[35] from the end of the 1860s till World War I (then managed by his son Julius).

-

Main facade

House at 19

[edit]1776[18]

Neo-Renaissance, elements of Eclecticism

During the second half of the 19th century, the landlord was Albert Ménard, a merchant and member of Bromberg city council.[36] The house was thoroughly refurbished in 2016.[37]

Main elevation is Neo-classic style, the gable is ornamented with many sculptural details, such as a mascaron.

-

Main elevation

-

Facade detail

-

Renovated elevations (19/21)

House at 20

[edit]First half of the 19th century[18]

In the 1880s, this building was the property of the Weisbein family, traders in cereals, living in Brücken Straße - today's Mostowa street[38]

-

Main Facade

House at 21

[edit]1895-1896[39]

The house was designed by A. Jenisch and Scheithauer. The edifice has been thoroughly refurbished in 2016.[37]

The facade mirrors the neighbouring one at 19, except for the gable which is less decorated here.

-

Main elevation

House at 22, corner with Pod Blankami street

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.735492, Reg.A/1561/1 (May 11, 2010)[29]

1800-1825[18]

Built in the aftermath of the Swedish invasion (1670s), it was the only stately building in which John III Sobieski and his family could be accommodated in 1677, on his way from Toruń. The walls of this house are 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) thick; royal rooms were on the second floor.[40] The front elevation has been built in 1834, the rest of the building till Pod Blankami street has been constructed in 1876. In 1933, the Bydgoszcz branch of Polish Historical Society, in consultation with other organizations decided to unveil a plaque in the facede of the house celebrating the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Vienna. This object in honor of John III Sobieski and Stephen Báthory was, however, placed on the wall of Church of the Poor Clares, and finally destroyed by Nazis in 1939.

There is also circumstantial evidence that in 1794 and 1807, the building has been used as headquarters of General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski.[41] Jan Dąbrowski left Bydgoszcz on January 23, 1807, to prepare a military action on Gdańsk. After Dąbrowski, the house has served as headquarters of French Marshal Lefebvre for a short period of time.

On June 8, 1813, Polish painter Maksymilian Piotrowski was born in this house. He came from a Polish bourgeois family, studied in German, French and Italian schools, and died as rector of the German Academy of Fine Arts in Kaliningrad.[42] After his death, his body was returned to Bydgoszcz where he is buried, in the Starofarny cemetery. On November 26, 1950, a commemorative bronze plaque, designed by Piotr Triebler and founded by the Society of Friends of Bydgoszcz has been unveiled to honore the painter.

In the 19th century, the building belonged to a foundation, "Father Kiełczyński", dedicated to the training of young theologians. On the ground floor was the oldest Polish bank, and warehouses and workshops of Polish industrialists. At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a well-known wine merchant, Carl Ardt.[43] During interwar period, Henryk Kaszubowski, a jeweller was installed on the ground floor.

The house is a two-storey town building with an attic. The overall shape is a closed quadrangle with a courtyard in the middle, between the Długa and Pod Blankami streets. The building has a vaulted, two-level basement, built probably at the end of the 18th: 6 meters high cellars were probably used to store wine.[44]

House at 23

[edit]1776[18]

Corner house with Jezuicka street, refurbished in 2015. In the 1880s, the house at then Friedrich Straße 49, was owned by Mrs Flora Indig, managing a shop selling material for writing and drawing.[45]

-

Main elevation of the corner

-

Elevation on Dluga street

House at 24

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.601281, Reg. A/744 (December 18, 1981)[29]

ca 1770[18]

Northern Europe Neo-Renaissance

This tenement has been rebuilt in 1885, following a design by Carl Stampehl. In Bydgoszcz, Carl Stampehl also designed :

- Emil Bernhardt tenement at 16 Gdańska Streetin 1884;

- Villa Carl Blumwe at 53 Nakielska street in 1893;

- House at 12 Długa street in 1866.

The triangular peak gable is adorned with pinnacles and a figural allegorical composition comprising industry theme.[14] It houses today, among others, a pub, "Zamek".

-

Main elevation

-

Detail of first level decoration

-

allegories on the gable

-

Wrought iron gate

House at 25

[edit]1776-1777[39]

Corner house with Jezuicka street, it mirrors with the same style the house at 23. In the second half of the 19th century, the building landlord, Moritz Aronsohn, had a printhouse there.[46] One can notice the preserved wrought iron balcony.

-

Main elevation of the corner

-

Facade onto Dluga street

House at 26

[edit]ca 1780[18]

In the entrance stands a preserved rococo gate from the 2nd half of the 18th century.[47]

-

Main elevation viewed from Długa street

-

Ornamented gate

Houses at 27 and 28

[edit]1780–1782,[39] (27)

1833,[18] (28)

-

Nr.27, main elevation and entrance to the backyard

-

Nr.28, main elevation

House at 29

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.702033, Reg.A/1261 (December 28, 2006)[29]

1778[18]

The tenement has been rebuilt in 1865.[1] In the 1890s, the landlord was a physician, Dr Emil Weithe, who had his office there (then Friedrich Straß 52).

-

Main elevation

-

Detail of an adorned framework window

-

Detail of an adorned framework window

House at 30

[edit]1782-1783[18]

The tenement has been rebuilt in the 19th century.[1]

-

Main elevation

-

Adorned street door

House at 31

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.723988, Reg. A/1402 (December 18, 2008)[29]

End of the 18th century[18]

Italian Neo-Renaissance

The building stands at the corner with Stefan Batory street. It has been rebuilt in 1862[14] in order to establish the "Hotel Rio": the edifice gained one floor and a hall party on the second, in the corner, which gave this characteristic tower, trendy at the time in British hotels.[48] The hotel stood there until 1939. Corner windows are adorned with stylized Corinthian pilasters, while last floor corner openings have semicircular windows. The whole façade is crowned with a profiled frieze and a cornice supported by ornamental consoles. The arrangement of the facade refers to renaissance palace architecture, with some monumental character.[48]

-

Advertising For "Rio restaurant" ca 1936

-

Main corner elevation

-

Windows with pilasters

-

Detail of the upper frieze

House at 32

[edit]1792[18]

Neoclassical architecture and Neo-Renaissance

The house has been built according to a design by Carl Stampehl,[14] as were houses at Nr.12, 24 and 46. It has been reconstructed in 1877–1878, on a command of Arnold Aronsohn, a merchant.[49]

-

Main elevation

-

Detail of the facade

-

Detail of the decorated top of the column

-

Winged head detail

-

Adorned gate

House at 33

[edit]1782[18]

The building stands at the corner with Stefan Batory street. It has been deeply renovated in the 2010s. in the 1860s, the owner Louis Levit had been running his printhouse in the premises.[50] In the 1890s, Leopold Arndt landlord at then Friedrich straße 54, had been running a shop selling exotic articles.[51]

-

The house before restoration

-

After renovation in 2014

Dom Ekonomisty at 34

[edit]1860[18]

Northern Europe Neo-Renaissance

In January 1781, David Meger and Samuel Konieczka bought this plot for construction, which began in 1860. Initially it was an apartment with a store room.[52] The tenement has been rebuilt in 1878 on a design of Carl Stampehl,[14] together with houses at Nr.12,24,35 and 46. After several owners, the house passed in 1920 into the hands of the "Trading Company - Chudziński and Maciejwski".[53] In 1934 the ground floor was used as a shop and part of the first floor housed a popular company in Bydgoszcz, "Hala Groszowa" (Penny hall), run by Chudziński and Majewski. In 1950, the shop was converted into a textile shop, "Bourett".[53] On June 30, 1961, the edifice was taken over by the Polish National Treasury with the City Residential Buildings Administration as designated administrator. Due to serious post-war damage, the building was earmarked as one of the first to undergo an overhaul, which began in 1976. Repairs lasted till 1982. The opening ceremonial of the seat of the Polish Economic Society in Bydgoszcz occurred in January 1983. It is still today the Provincial Department of Polish Economic Society in Bydgoszcz, busy with activity. Inside are 3 classrooms, where lectures, seminars, conferences and meetings are held.[53]

Worth noticing are the beautiful stained glass windows and the Art Nouveau furniture still preserved inside.

-

Facade giving onto Długa street

-

View of the corner

-

Architectural decoration detail

House at 35

[edit]1781-1783[39]

Neo-Renaissance & Neoclassical architecture

This tenement has been rebuilt in 1877–1878 on a design of Carl Stampehl,[14] together with houses at Nr.12, 24, 34 and 46.

-

Facade onto Długa street

-

Facade after renovation

Hotel Ratuszowy at 37

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.A/374/1 (October 10, 1993)[29]

1880-1884[39]

Neoclassical architecture & Eclecticism

The original edifice erected between 1830 and 1833 was designed to be an outbuilding for the administrative purposes benefit of the Town Hall. Inside were planned a large and a small session hall, the mayor's office together with municipal offices. The building had originally two-story, with an attic covered with a mansard roof.[54] As the city grew, the building's area turned out to be insufficient despite numerous conversions. In 1879, the new city hall moved to the former Jesuit College on the Old Market, much larger and the existing building was sold the same year to a hotelier, Julius Lengning.[55]

He soon started the reconstruction and renovation of the building in order to adapt it to its new function. Main builder was master bricklayer Gustav Weihe[54] and master carpenter Heinrich Mautz. The former had designed in 1876 a house at 61 Dworcowa Street. Hotel erection, completed 1881, encompassed the addition of a third floor, the reconstruction of the interior on the ground floor and upgrading the arrangement of the facade. On the hotel's ground floor, a large entrance hall, shops, guest rooms and "business" rooms were made, the rear part of the hotel being reserved for residential space.[54] The rooms were equipped with toilets and facilities with hot and cold water. In the hotel yard, at the back of the building, stood a large restaurant, underneath were a kitchen and a utility room. Facade decorations were of neoclassical style, much richer than the surroundings with meanders motifs under the windows of the attic and friezes crowning the cornice.[12]

In 1908, Julius Lengning sold the property to a wine tradesman from Olsztyn, Antonow Kretschman, who carried out a modernization of the hotel: in 1909, central heating was installed, the attic furnished with additional rooms, a wine cellar and a beer hall opened.[54] After World War I, three other owners succeeded to Antonow Kretschman.[56] Until 1945, the hotel kept its name, "Hotel Lengning", unchanged, despite ownership shifts. After 1945, the building housed the dormitory of the Technical School of Electrical Engineering -a plaque on the wall commemorates it- until 1965, when it resumed its hosting role, under the actual name, City Hall Hotel (Polish: Hotel Ratuszowy). The hotel underwent a recent refurbishing in 2020, changing the appearance of the facade, especially at ground floor level.[55]

The building is erected according to a rectangle footprint, with small inner courtyards. The ground floor is decorated with a bossages. The windows of the first and second floors have a rich, architectural settings.[57] Initially, the main entrance was located in the middle of the facade, giving wayto a monumental staircase. The cellars under the building have three levels, some of them display arches, but not open to the public.[58]

-

Facade onto Długa street

-

Detail of the decoration on the facade

-

Detail of a window

-

Advertising ca 1917

House at 39

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.601282, Reg. A/984 (February 4, 1992)[29]

Second half of the 19th century[18]

-

Facade onto Długa street

-

Detail of facade window decoration

House at 40

[edit]1778-1779[18]

The tenement has been recently renovated. From 1878 till the early 1910s, it has been the property of Joseph Lewinsohn, a merchant of sewing and working machines.[59]

-

Facade onto Długa street before restoration

-

Renovated facade

City Public Library at 41

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.601283, Reg.A/985 (February 4, 1992)[29]

1798[18]

Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Baroque

This building has been erected in 1798 for the needs of the court of West Prussia. It became in 1903 property of the Kingdom of Prussia, and serves as the seat of the court hearing till the completion of the edifice at 3 Jagiellońska street. Later on it housed the Municipal Police (Friedrichstraße 58).[60]

From 1908 onward, the edifice has been welcoming the Municipal Library. Between both library buildings runs the narrow Zaułek street: to unite the architectural ensemble, a covered passage called the "Bridge of Sighs" (Polish: Most Westchnień), has been built in 1920.

Since the 1920s, the Municipal Library owns the edifice. The outbuilding on the first floor harbours a collection of antique books called the Bibliotheca Bernardina.[57] These precious volumes come from the Bernardines library installed in the 16th century in Bernardyńska Street. This building has a "L" shape with a side outbuilding and the main entrance on the south elevation. The facades are divided by vertical pilasters and horizontal cornices. The vaulted cellars are still preserved.[57] The edifice is topped by a Mansard roof with eyelid dormers.

-

Elevations of the building

-

Facade onto Długa street

-

House at42

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.728853, Reg.A/1538 (September 1, 2009)[29]

Last quarter of the 18th century[18]

The house has been rebuilt around 1875–1900.[1]

-

Facade onto Długa street

-

Facade onto Długa street

Houses at 45 to 51

[edit]1783-1786[39] (45)

Last quarter of the 18th century[18] (46 & 50)

1865[18] (47)

18th century[18] (48 & 51)

1875-1900[18] (49)

Northern Europe Neo-Renaissance

Together with houses at Nr.12, 24 and 34, the edifice at Nr.46 has been rebuilt in 1879 on a design of Carl Stampehl:[14] it displays nice rosettes on the facade.

-

Facade of 45

-

Main Facade of 46

-

Rosettes at N.46

-

Facade of N7

-

Facade of 48

-

Main facade of 49

-

Elevation of 50

-

Main facade of 51

House at 52

[edit]Last quarter of the 18th century[18]

The building is delimited by streets Długa, Jan Kazimierz and Pod Blankami. It houses the seat of the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Regional Administrative Court. The origins of the building are not well documented, but it is known that in this place stood brick or wattle and daub buildings in the 15th century. In 2008, archaeological research estimated the remains of a brick building at 52 dating back between the 16th to the 18th centuries.[4] The outline of the current building, appears on city documents in 1876. At the beginning of the 20th century, the tenement housed several shops: Blumenthal paper shop, hairdresser and butcher Kaschika Josel, then Rose and Gertrude Wolff selling kosher meats. On the first floor officiated a lawyer Mr Jakobsohn, the second was the tailor establishment of Mr Ludwig, and on the third level Miss Seifert gave piano lessons. These shops and craft were at that time mostly owned by people of Jewish origin.[7] From 1909 to 1920, the ground floor has housed the set of "Dziennik Bydgoski" (The Official of Bydgoszcz), established by journalist Jan Teska.[7] It was the most important Polish newspaper in Bromberg during the Prussian era and the most popular in the city during interwar period. On the façade of the building onto Długa street, a commemorative plaque in memory of Jan Teska as a mainstay of Polish in the first decades of the 20th century in Bydgoszcz has been unveiled in 1996. In 2002, the Regional Supreme Administrative Court, renamed in 2004 the Provincial Administrative Court, moved to this building. For this occasion, a complete renovation has been carried out as well as an adjustment of interiors to the needs of the judiciary activity.

The building has a horseshoe footprint. The tenement has a cellar, two-storey and an attic. The ground floor is decorated with bossages. on the facade, floors are separated with cornices, with a grander one on the top. The windows of the first and second floors display architectural detailed decoration.

-

Dziennik Bydgoski advertising ca 1929

-

View from Pod Blankami street

-

Facade onto Długa street

-

Plaque in memoriam of Jan Teska

House at 53

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.706927, Reg.A/1325/1-2 (July 12, 2007)[29]

The building has been reconstructed in 1870.[1] The rear annex building, opening onto Zaułek street, has been used as a granary during the second half of the 19th century. At this period, the landlord was Carl Wenzel, merchant, member of Bromberg city council, who lived at Danziger Straße 13 (today's Gdańska street 17).[61]

-

General view from Długa street

-

Detail of the ornaments on the facade

-

Facade of the rear building onto Zaułek street

Houses at 54/58

[edit]1767-1774[39] (54)

1877-1878[18] (55)

Last quarter of the 19th century[18] (56)

Second half of the 19th century[18] (58)

The house at 56 had its second floor, with a new loft, rebuilt by architect Anton Hoffmann. At the beginning of the 21st century, these houses have been rebuilt. According to Józef Święcicki, in 1907, a restaurant, "Twardowski", stood there.

-

Facades of Nr.54 (right) and 56 (left)

-

Main facade of Nr.55

-

Facade of Nr.58

-

Figure on Nr.58 facade

House at 62

[edit]Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.601284, Reg.A/343/1-2 (February 24, 2005)[29]

1850s[18]

The building has a second entry through Pod Blankami street 57. The cellar located under the courtyard is also listed on the heritage list.

-

General view from Długa street

-

Detail of the ornaments on the facade

Houses at Nr.72 & 74

[edit]1778[18] (72)

1894[18] (74)

Both houses have been reconstructed during the second half of the 19th century.

-

Facades of Nr.72 (right) and 74 (left)

-

Facade of Nr.74

-

Detail of the gable at Nr.74

House at 76

[edit]1870,[18] by Friedrich Meyer

One can notice the pilasters as part of the avant-corps, as a reference to Roman architecture. The facade lower levels display Doric style, higher ones follow Corinthian style. Friezes delineate the facade, additionally decorated with floral motifs. The whole elevation is topped with a triangular Pediment with a tondo displaying a figure of a baby's head.[12]

-

General view

-

View from Długa street

-

Detail of the pediment and the upper facade

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Umiński, Janusz (1996). Przewodnik: Bydgoszcz. Bydgoszcz: Regionalny Oddział PTTK "Szlak Brdy".

- ^ Czachorowski, Antoni (1997). Atlas historyczny miast polskich. Tom II Kujawy. Zeszyt I Bydgoszcz. Toruń: Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika.

- ^ Derenda, Jerzy (2006). Piękna stara Bydgoszcz. Tom I z serii: Bydgoszcz miasto na Kujawach. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. p. 217. ISBN 83-916178-0-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Siwiak, Wojciech (2007). Z przeszłości ulicy Długiej. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Dygaszewicz, Elżbieta (1996). Bydgoszcz przedlokacyjna i lokacyjna w świetle nadzorów i archeologicznych badań ratowniczych. Materiały do Dziejów Kultury i Sztuki Bydgoszczy i Regionu. zeszyt 1. Bydgoszcz: PRACOWNIA DOKUMENTACJI I POPULARYZACJI ZABYTKÓW WOJEWÓDZKIEGO OŚRODKA KULTURY W BYDGOSZCZY.

- ^ a b Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria (2002). Rozwój budownictwa hotelowego w Bydgoszczy w 2. połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 7. Bydgoszcz: PRACOWNIA DOKUMENTACJI I POPULARYZACJI ZABYTKÓW WOJEWÓDZKIEGO OŚRODKA KULTURY W BYDGOSZCZY.

- ^ a b c d e Janiszewska-Mincer, Barbara (2008). Ulica Długa na początku XX wieku. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Joseph Święcicki "Bromberg" 1907

- ^ Błażejewski, Krzysztof (21 July 2014). Długa ulica towarów krótkich. Bydgoszcz: Express Bydgoski.

- ^ ka (15 April 2008). "Tramwaj znowu stoi na Długiej". bydgoszcz.gazeta.pl. bydgoszcz.gazeta. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ Weckwerth, Marek (2 June 2016). "Święto ulicy Długiej w Bydgoszczy - w piątek i sobotę". pomorska.pl. Gazeta pomorska. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria (2003). Echa architektury starożytnej w budowlach bydgoskich XIX i początku XX wieku. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. zeszyt 8. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria. Przegląd stylów występujących w bydgoskiej architekturze drugiej połowy XIX i początku XX stulecia. Bydgoszcz.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria (2007). Neorenesans w architekturze bydgoskich kamienic. Kronika Bydgoska XXVIII. Bydgoszcz: TOWARZYSTWO MIŁOŚNIKOW MIASTA BYDGOSZCZY.

- ^ a b c Uchwala NR XLI/875/13 RADY MIASTA BYDGOSZCZY, 24 April 2013

- ^ Aładowicz, Krzysztof (27 January 2010). "Długa-reaktywacja. Czy przywrócą ją do życia?". bydgoszcz.gazeta.pl. bydgoszcz.gazeta. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ al (9 November 2007). "Bydgoskie autografy ujrzysz w alei na Długiej". bydgoszcz.gazeta.pl. bydgoszcz.gazeta. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Gminna Ewidencja Zabytków Miasta Bydgoszczy. Program Opieki nad Zabytkami miasta Bydgoszczy na lata 2013–2016

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1915: auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1915. p. 157.

- ^ Bydgoszcz Guide. Bydgoszcz: City of Bydgoszcz. July 2014. p. 51. ISBN 83-917786-7-3.

- ^ Derkowska-Kostkowska, Bogna (2004). Anton Hoffmann - tradycja i profesjonalizm w bydgoskiej architekturze. Kronika Bydgoska XXVI. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Milosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. p. 456.

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1900 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1900. p. 73.

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1880: auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Mittler. 1880. p. XVIII.

- ^ Siwiak Wojciech, Siwiak Anna (2006). Nowożytny strop drewniany z kamienicy przy ul. Długiej 9 w Bydgoszczy. Przyczynek do początku murowanej zabudowy mieszkalnej i wystroju wnętrza w XVI-XVIII wieku. Ziemia Kujawska t. XIX. Inowrocław-Włocławek: Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne.

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg mit Vorvorten. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1907. p. 345.

- ^ a b Kuczma, Rajmund (1998). Winiarnia: Jan Jakub Goerdel- ul. Długa 10. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 259–261.

- ^ a b Allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger fur Bromberg 1855. Bromberg: Aronsohn. 1855. p. 54.

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg mit Vorvorten. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1917. p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Załącznik do uchwały Nr XXXIV/601/13 Sejmiku Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego z dnia 20 maja 2013 r.

- ^ wb (6 June 2014). "Jan Biziel i Alojzy Stryszyk mają swoje tablice na Długiej". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. bydgoszcz.wyborcza. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Wojciechowski, Sławomir (27 May 2012). "Wspomnienie Alojzego Stryszyka". polonia1920.pl. polonia1920.pl. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1903 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1903. p. 38.

- ^ a b "Muzeum Mydła i Historii Brudu in Bydgoszcz". muzeummydla.pl. muzeummydla. 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1890 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1890. p. 31.

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1890 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1890. p. 31.

- ^ "Names". Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für die Stadt Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1872. Bromberg: Mittler. 1872. p. 50.

- ^ a b dss (12 July 2016). "Kamienice na Długiej już nie straszą. Wręcz przeciwnie". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "Names". Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1886. Mittler. 1886. p. 174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jasiakiewicz, Roman (24 April 2013). Uchwala NR XLI/875/13. Bydgoszcz: Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 71–73.

- ^ Jurkiewicz, Zenon (1994). Dom przy ul. Długiej. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 167–173.

- ^ In a letter to General. Amilkar Kosinski, the organizer of armed force department Bydgoszcz, dated January 5, 1807. Łowicz, General Dabrowski, announcing a march through Bydgoszcz his 10-thousandth of the body and about 4,000 horses, points out that he hastens to Bydgoszcz, "driving day and night" being asked about making it in City lodging in the same place in which he lived, in October 1794. In a letter of 20 January 1807. gen. Dabrowski says that headquarters it is located on Długa Street (die Lange-Gasse)

- ^ Bydgoszcz Guide. Bydgoszcz: City of Bydgoszcz. July 2014. p. 93. ISBN 83-917786-7-3.

- ^ Derenda, Jerzy (2006). Piękna stara Bydgoszcz – tom I z serii Bydgoszcz miasto na Kujawach. Bydgoszcz: Praca zbiorowa. Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. p. 218.

- ^ Idczak, Katarzyna (2 July 2012). "Wiosna starych murów". expressbydgoski.pl/bydgoszcz. expressbydgoski.pl. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "Names". Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1880. Mittler. 1880. p. 36.

- ^ "Names". Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für die Stadt Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1872. Bromberg: Mittler. 1872. p. 2.

- ^ T. Chrzanowski, M. Kornecki (1977). Katalog Zabytków Sztuki w Polsce. T. 3, Bydgoszcz i okolice. Warszawa. p. 26.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b BRĘCZEWSKA-KULESZA, DARIA (2002). Rozwój budownictwa hotelowego w Bydgoszczy w 2. połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku, in MATERIAŁY DO DZIEJOW KULTURY I SZTUKI BYDGOSZCZY I REGIONU, t.7. Bydgoszcz: PRACOWNIA DOKUMENTACJI I POPULARYZACJI ZABYTKÓW WOJEWÓDZKIEGO OŚRODKA KULTURY W BYDGOSZCZY. p. 61.

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1880: auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Mittler. 1880. p. 13.

- ^ "Names". Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für die Stadt Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1869. Bromberg: Louis Levit. 1869. p. 52.

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1890: auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1890. p. 7.

- ^ księga nr 530, i nr 2151, tom II, karta 103. Bydoszcz Archiwum.

- ^ a b c Kaczmarczek, Henryk (1986). Dom Ekonomisty przy ul. Dlugiej. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towaezystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydoszczy. pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c d "Historia". hotelratuszowy. Materiały opracowane przez Wojewódzki Ośrodek Kultury i Sztuki "Stara Ochronka" w Bydgoszczy. 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b za (21 April 2020). "Kiedyś był tam ratusz, później hotel. Blisko 200-letnia kamienica w Bydgoszczy zostanie wyremontowana". expressbydgoski.pl. Polska Press Sp. z o. o. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ Lewińska, Aleksandra (9 June 2011). "130 lat Ratuszowego. Hotel na 18. południku". bydgoszcz.gazeta.pl/bydgoszcz. bydgoszcz.gazeta.pl. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Parucka, Krystyna (2008). Zabytki Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: minikatalog. "Tifen".

- ^ Katarzyna Oleksy "Pokoje i noclegi w ratuszu" Express Bydgoski 10 czerwca 2011

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1878: auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Mittler. 1878. p. 66.

- ^ "Straßen". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1905 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Ditmann. 1905. p. 45.

- ^ "Names". Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1890 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1890. p. 221.

External links

[edit]- Hotel Ratuszowy in Długa street

- (in Polish) Polish Economic Society in Bydgoszcz

- (in Polish) Bydgoszcz page about "Autographs alley"

- (in Polish) Bydgoszcz Museum of Soap and History of Dirt

Bibliography

[edit]- (in Polish) Derenda, Jerzy (2006). Piękna stara Bydgoszcz – tom I z serii Bydgoszcz miasto na Kujawach. Praca zbiorowa. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- (in Polish) Bręczewska-Kulesza, Daria. Przegląd stylów występujących w bydgoskiej architekturze drugiej połowy XIX i początku XX stulecia. Bydgoszcz.

- (in Polish) Jastrzębska-Puzowska, Iwona (2005). Od miasteczka do metropolii. Rozwój architektoniczny i urbanistyczny Bydgoszczy w latach 1850–1920. Toruń: Wydawnictwo MADO. ISBN 9788389886385.

- (in Polish) Umiński, Janusz (1996). Bydgoszcz-Przewodnik. Bydgoszcz: Regionalny Oddział PTTK "Szlak Brdy".

- (in Polish) Jurkiewicz, Zenon (1994). Dom przy ul. Długiej. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 167–173.

- (in Polish) Kaczmarczek, Henryk (1986). Dom Ekonomisty przy ul. Dlugiej. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 7–9.

- (in Polish) Rymkiewicz, Anna (1998). Hugon Brasicke i jego biblioteka. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 191–196.

- (in Polish) Kuczma, Rajmund (1998). Winiarnia:Jan Jakub Goerdel- ul. Długa 10. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 259–262.