Hurricane Irma

Irma at peak intensity while making landfall in Saint Martin on September 6 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 30, 2017 |

| Remnant low | September 12, 2017 |

| Dissipated | September 13, 2017 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 180 mph (285 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 914 mbar (hPa); 26.99 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 134 total |

| Damage | $77.2 billion (2017 USD) (Seventh-costliest tropical cyclone on record; costliest in Cuban history) |

| Areas affected | Cape Verde, Leeward Islands (especially Barbuda, Saint Barthélemy, Anguilla, Saint Martin and the Virgin Islands), Greater Antilles (Cuba and Puerto Rico), Turks and Caicos Islands, Jamaica, The Bahamas, Eastern United States (especially Florida) |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History

Effects

Other wikis | |

Hurricane Irma was an extremely powerful and devastating tropical cyclone that was the first Category 5 hurricane to strike the Leeward Islands on record, followed by Maria two weeks later. At the time, it was considered the most powerful hurricane on record in the open Atlantic region, outside of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, until it was surpassed by Hurricane Dorian two years later. It was also the third-strongest Atlantic hurricane at landfall ever recorded, just behind the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane and Dorian.[1] The ninth named storm, fourth hurricane, second major hurricane,[nb 1] and first Category 5 hurricane of the extremely active 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, Irma caused widespread and catastrophic damage throughout its long lifetime, particularly in the northeastern Caribbean and the Florida Keys. It was also the most intense hurricane to strike the continental United States since Katrina in 2005, the first major hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Wilma in the same year, and the first Category 4 hurricane to strike the state since Charley in 2004. The word Irmageddon was coined soon after the hurricane to describe the damage caused by the hurricane.[3]

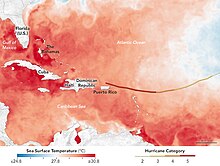

Irma developed from a tropical wave near the Cape Verde Islands on August 30. Favorable conditions allowed Irma to rapidly intensify into a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson wind scale by late on August 31. The storm's intensity fluctuated between Categories 2 and 3 for the next several days, due to a series of eyewall replacement cycles. On September 4, Irma resumed intensifying, becoming a Category 5 hurricane by early on the next day. Early on September 6, Irma peaked with 1-minute sustained winds of 180 mph (290 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 914 hPa (27.0 inHg). Irma was the second-most intense tropical cyclone worldwide in 2017 in terms of barometric pressure, and the strongest worldwide in 2017 in terms of wind speed. Another eyewall replacement cycle caused Irma to weaken back to a Category 4 hurricane, but the storm re-attained Category 5 status before making landfall in Cuba. Although Irma briefly weakened to a Category 2 storm while making landfall on Cuba, the system re-intensified to Category 4 status as it crossed the warm waters of the Straits of Florida, before making landfall on Cudjoe Key on September 10. Irma then weakened to Category 3 status, prior to another landfall in Florida on Marco Island later that day. The system degraded into a remnant low over Alabama and ultimately dissipated on September 13 over Missouri.

The storm caused catastrophic damage in Barbuda, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Anguilla, and the Virgin Islands as a Category 5 hurricane. The hurricane caused at least 134 deaths: one in Anguilla; one in Barbados; three in Barbuda; four in the British Virgin Islands; 10 in Cuba; 11 in the French West Indies; one in Haiti; three in Puerto Rico; four on the Dutch side of Sint Maarten; 92 in the contiguous United States, and four in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Hurricane Irma was the top Google searched term in the U.S. and globally in 2017.[4]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring a tropical wave over western Africa on August 26.[5] Developing into a tropical depression just west of the Cape Verde Islands early on August 31, becoming Tropical Storm Irma shortly afterwards.[6] Under favorable conditions, Irma underwent rapid intensification, becoming a major hurricane on September 1. Within a 48-hour period, the hurricane's intensity had increased by 65 mph (105 km/h).[6] Fluctuations occurred over the next few days due to internal processes, as The first aircraft reconnaissance mission discovered an eye 29 mi (47 km) in diameter and surface winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) on September 3.[7][8]

| Strongest landfalling Atlantic hurricanes† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Wind speed | ||

| mph | km/h | ||||

| 1 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 185 | 295 | |

| Dorian | 2019 | ||||

| 3 | Irma | 2017 | 180 | 285 | |

| 4 | Janet | 1955 | 175 | 280 | |

| Camille | 1969 | ||||

| Anita | 1977 | ||||

| David | 1979 | ||||

| Dean | 2007 | ||||

| 9 | "Cuba" | 1924 | 165 | 270 | |

| Andrew | 1992 | ||||

| Maria | 2017 | ||||

| Source: HURDAT,[9] AOML/HRD[10] | |||||

| †Strength refers to maximum sustained wind speed upon striking land. | |||||

As Irma continued approaching the Leeward Islands, the hurricane underwent a second and more robust period of rapid intensification, becoming a Category 5 hurricane early on September 5. The extremely powerful hurricane continued to intensify, with maximum sustained winds peaking at 180 mph (290 km/h) shortly afterwards. Irma acquired annular characteristics around this time, with the storm exhibiting a large, symmetric CDO and an impressive satellite appearance.[11] Irma continued to intensify while approaching the northern Leeward Islands. At 05:45 UTC on September 6, Irma made landfall along the northern coast of Barbuda at peak intensity, with the storm's central minimum pressure having bottomed out at 914 mbar (27.0 inHg) – this was the lowest in the Atlantic since Dean in 2007; the storm also made landfall with maximum sustained winds of 180 mph (290 km/h). Irma continued to maintain its peak intensity until 12:00 UTC on September 6 and made additional successive landfalls on that same day, at 11:15 UTC on Sint Maarten, and at 16:30 UTC on Virgin Gorda, in the British Virgin Islands.[6]

Irma maintained Category 5 strength for several days as it passed north of the Greater Antilles. After beginning an eyewall replacement cycle, Irma weakened to a Category 4 hurricane as it passed south of the Turks and Caicos Islands early on September 8, subsequently ending the 60-hour contiguous period of Irma maintaining Category 5 intensity, the second-longest any Atlantic storm had maintained winds above 156 mph (251 km/h) – behind only the 1932 Cuba hurricane. The hurricane then began tracking more to the west due to the intensification of a subtropical ridge to its north. Once the eyewall replacement cycle was complete, Irma began to re-intensify, and it re-attained Category 5 intensity at 18:00 UTC that day east of Cuba, before the hurricane then made landfall in Cayo Romano, Cuba, at 03:00 UTC on September 9, with winds of 165 mph (266 km/h). This made Irma only the second Category 5 hurricane to strike Cuba in recorded history, after the 1924 Cuba hurricane. As the eye of Irma moved along the northern coast of Cuba, gradual weakening ensued due to land interaction, with the eye becoming cloud-filled and the intensity falling to a high-end Category 2 storm later on September 9.[6]

After slowing down late on September 9, the hurricane turned northwestward towards Florida around the southwestern edge of the subtropical high to its northeast and a low-pressure system that was located over the continental United States. Moving over the warm waters of the Straits of Florida, Irma quickly restrengthened to a Category 4 hurricane at 06:00 UTC on September 10, as deep convection improved and the eye became better defined.[6] The cyclone made landfall in Cudjoe Key, Florida, at 13:00 UTC on September 10, at Category 4 intensity, with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h). Increasing wind shear and land interaction caused the satellite appearance of the storm to become ragged later that day, and Irma weakened to Category 3 intensity before making its seventh and final landfall at 19:30 UTC, in Marco Island, Florida, with sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Once Irma had moved inland, it began to accelerate to the north-northwest, while rapid weakening began to occur due to the increasing wind shear, land interaction, and dry air, with the storm falling below Category 3 intensity hours after landfall. Irma finally weakened to a tropical storm on September 11 as it entered southern Georgia,[6] while transitioning into an extratropical cyclone,[12] degenerating into a remnant low early on September 12. The remnants dissipated over Missouri on September 13.[6]

Preparations

Caribbean

Given that Irma's forecast track was along much of the Caribbean island chain, hurricane warnings were issued for the northern Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, and parts of Hispaniola on September 5.[6]

In Antigua and Barbuda, residents safeguarded their homes and cleaned up their properties in anticipation of strong winds. Emergency crews were put on standby at public shelters and hospitals by September 5 to assist with any evacuations.[13] Expecting a direct hit, more than half of the residents on Barbuda took shelter,[14] and relief supplies were preemptively mobilized.[15] The National Emergency Management Organization on Saint Lucia urged small craft operators and swimmers to be mindful of forecasts for high surf.[16] Small Craft Warnings and High Surf Advisories were hoisted for Dominica, where residents were urged to remain vigilant of the potential for high waves, landslides, and flooding.[17]

In Guadeloupe, low-lying and cliff-edge homes were evacuated at the threat of flooding and erosion. Schools and public businesses closed on September 5 and 6. Hospitals stocked up on three days' worth of supplies and checked the functionality of their generators.[18][19] Of the island's 32 communes, 22 activated their emergency plans; 1,500 people were urged to take shelter.[20] The island sustained relatively minor damage and became the base for relief efforts on Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy.[21] Though the core of the hurricane was expected to remain north of the island, a yellow alert was issued for Martinique due to the likelihood of rough seas.[22] The island dispatched relief supplies and military reinforcements to its neighboring islands of Guadeloupe, Saint Martin. and Saint Barthélemy, which faced a greater risk of a direct impact.[23]

On September 4, Puerto Rico declared a state of emergency.[24] By September 6, the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency had deployed response teams in Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands. Supplies, including food rations, medical supplies, and blankets, were pre-staged in strategic locations on the islands for distribution.[25]

On September 5, the Dominican Republic activated the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters, thus providing for humanitarian satellite coverage;[26] the United States and Haiti followed suit two days later.[27][28] According to officials, 11,200 people were evacuated from vulnerable areas prior to the storm's arrival.[29] Approximately 7,400 tourists were moved to Santo Domingo, away from beach resorts.[30] In Haiti, government officials and aid organizations struggled with early preparation and evacuation efforts. While some officials blamed reluctance and indifference on the part of the population, others "admitted they were not prepared for the onslaught and no mandatory evacuation orders were in place ahead of Irma's approach."[30][31] Local officials contended that they had not received promised funds, supplies, or equipment from the national government. The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti prepared its 1,000 peacekeepers and engineers to assist.[32]

In the Turks and Caicos, evacuation orders were issued for low-lying areas starting September 5. Schools were closed, government buildings were boarded up, and shelters were opened.[33] Officials spread warnings to residents in English, Creole, and Spanish via social media, radio, SMS text, and WhatsApp.[34] In The Bahamas, the government began preparations the week prior to the hurricane's arrival, including securing national sports facilities to use as shelters.[35] By September 7, the government had evacuated 1,609 people by air from the southern islands, including 365 from Bimini.[36] Controlled cutting of the power supply to southern and central Bahamian islands was conducted in advance of the storm.[37] Shelters were made available, though usage was low due to most evacuees staying with family on other islands.[38] Of the 2,679 foreign tourists still in The Bahamas on September 7, about 1,200 were being housed at Atlantis Paradise Island, one of the most hurricane-ready structures in the country.[39]

In Cuba, meteorologists did not initially predict a direct hit.[40] Fuel conservation was enacted in Camagüey Province to ensure that enough would be available during post-storm power outages.[41] The Civil Defense evacuated nearly one million people from low-lying areas, including thousands of Canadian and European tourists in the Jardines del Rey.[42][40] Dolphins at a Cayo Guillermo resort were evacuated by helicopter.[40]

Mainland United States

The NHC issued several watches and warnings for the Southeastern United States. The first watches and warnings were issued at 15:00 UTC on September 7, which was a hurricane watch from the Jupiter Inlet to Bonita Beach, including the Florida Keys and Lake Okeechobee. The watches and warnings were extended into Georgia and South Carolina on September 9. At 21:00 UTC on that day, the advisories reached their maximum extent, with a hurricane warning covering the entire east coast of the state, the west coast from Indian Pass southward, and the Florida Keys; a hurricane watch was in place from the Florida–Georgia state line to Edisto Beach, South Carolina; and there were two tropical storm warnings, one in Florida from Indian Pass to the Okaloosa–Walton county line and the other from the Florida–Georgia state line to the South Santee River in South Carolina. Watches and warnings were gradually discontinued as Irma moved inland and weakened, with all of them canceled by early on September 12.[6]

Florida

On September 4, Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency. Governor Scott placed 100 members of the Florida National Guard on duty to assist in preparations. All 7,000 troops were ordered to be on duty by September 8.[43] Officials advised residents to stock their hurricane kits.[44] The state coordinated with electrical companies in order for power outages to be restored as quickly as possible, extending resources such as equipment, fuel, and lodging for the approximately 24,000 restoration personnel who had been activated. Governor Scott suspended tolls on all toll roads in Florida, including the turnpike. All state offices in Florida were closed from September 8 to September 11, while public schools, state colleges, and state universities in all 67 counties were closed during the same period. The Florida Department of Education coordinated with school districts as the need for transportation by school buses and opening shelters arose. By September 9, more than 150 state parks were closed.[45] Throughout the state, almost 700 emergency shelters were opened. The shelters collectively housed about 191,764 people,[43] with more than 40% of them staying in a shelter in South Florida.[46] Additionally, more than 60 special needs shelters were opened, which housed more than 5,000 people by September 9.[45]

Many airports across the state, particularly in Central and South Florida, were closed.[45] Nearly 9,000 flights intending to arrive in or depart from Florida were canceled.[47] Along Florida's coasts, most seaports were closed or opened with restricted access.[45] For the fifth time in its 45-year history, the Walt Disney World Resort was completely closed due to the storm. Its theme parks, water parks, and Disney Springs were all closed by 9:00 p.m. on September 9 and remained closed until September 12. Other Orlando-area theme parks, including Universal Orlando Resort and SeaWorld Orlando, were also closed.[48] The Kennedy Space Center was closed from September 8 to September 15.[49]

An estimated 6.5 million Floridians were ordered to evacuate, mostly those living on barrier islands or in coastal areas; in mobile or sub-standard homes; and in low-lying or flood prone areas. Mandatory evacuations were ordered for portions of Brevard, Broward, Citrus, Collier, Dixie, Duval, Flagler, Glades, Hendry, Hernando, Indian River, Lee, Martin, Miami-Dade, Orange, Palm Beach, Pasco, Pinellas, Sarasota, Seminole, St. Lucie, Sumter, and Volusia counties. All of Monroe County, where the Florida Keys are located, was placed under a mandatory evacuation.[45] Residents in communities near the southern half of Lake Okeechobee were also ordered to leave. Additionally, voluntary evacuation notices were issued for all or parts of Alachua, Baker, Bay, Bradford, Charlotte, Columbia, Desoto, Hardee, Highlands, Hillsborough, Lake, Manatee, Okeechobee, Osceola, and Polk counties.[45]

A record 6.5 million Floridians evacuated, making it the largest evacuation in the state's history. Evacuees caused significant traffic congestion on northbound Interstate 95, Interstate 75, and Florida's Turnpike, exacerbated by the fact that the entire Florida peninsula was within the cone of uncertainty in the NHC's forecast path in the days before the storm, so evacuees from both coasts headed north, as evacuees would not be safer by fleeing to the opposite coast.[43] Fuel was in short supply throughout peninsular Florida during the week before Irma's arrival, especially along evacuation routes, leading to hours-long lines at fuel stations and even escorts of fuel trucks by the Florida Highway Patrol.[50]

Use of the left shoulder as a lane for moving traffic was allowed on northbound Interstate 75 from Wildwood to the Georgia state line beginning September 8 and on eastbound Interstate 4 from Tampa to State Road 429 near Celebration for a few hours on September 9. It was the first time that the shoulder-use plan, which was introduced at the start of the 2017 hurricane season, was implemented by the state for hurricane evacuations.[43] The shoulder-use plan was implemented in place of labor- and resource-intensive contraflow lane reversal, in which both sides of an interstate highway are used for one direction of traffic.[51][52]

Officials from the Environmental Protection Agency, which had been criticized for its response to Hurricane Harvey, took special measures to inspect and secure hazardous materials, especially at Superfund sites.[53] Direct Relief, a disaster relief organization, coordinated with local health centers and provided resources to help facilities on the front lines of Floridian and Puerto Rican communities.[54]

Elsewhere

Georgia Governor Nathan Deal declared a state of emergency initially for all six coastal counties on September 6, but eventually expanded the declaration to 94 counties south of Atlanta metropolitan area, and then the entire state on September 10. Atlanta was placed under its first-ever tropical storm warning.[55][56] Governor Deal ordered mandatory evacuations for all areas east of Interstate 95 on September 7, before extending the order to the entirety of Chatham County and low-lying areas west of I-95 on the following day.[57] In total, 540,000 people on the Georgia coast were ordered to leave.[58] Contraflow lane reversal for Interstate 16 took effect on the morning of September 9 from Savannah to Dublin, Georgia.[59] All Georgia state parks were open for free to evacuees, as was the 800-acre camping area at Atlanta Motor Speedway.[60] Reversible HOT lanes on Interstate 75 in Georgia through south metro Atlanta were open 24 hours northbound with no tolls.[61]

North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper declared a state of emergency on September 6,[62] with South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster following suit the same day.[63] Governor of Virginia Terry McAuliffe declared a state of emergency on September 8 in order to protect Virginia residents and to mobilize resources in support of neighboring states.[64] Officials in New Orleans stated that there would not be much time for preparations if Irma failed to make the projected northward turn, but that South Texas or Florida would not be a good evacuation destination.[65] On September 10, Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam issued an executive order allowing medical professionals in other states to practice in Tennessee to aid Hurricane Irma evacuees. This order also allowed pharmacies to give out 14-day supplies of medicine, and gave women and children from outside the state the ability to participate in the Tennessee Department of Health programs.[66] Bristol Motor Speedway,[67] Talladega Superspeedway,[60] and Charlotte Motor Speedway all opened their campgrounds to evacuees free of charge.[67]

Sports

In professional sports, the Miami Dolphins–Tampa Bay Buccaneers game scheduled for September 10 at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami was postponed to November 19 due to the storm's threat. The Dolphins left early for their road game against the Los Angeles Chargers.[68] The Tampa Bay Rays and New York Yankees moved their September 11–13 series from Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg to Citi Field in Queens.[68] Minor League Baseball's Florida State League, Carolina League, and Southern League called off their championship finals and as a result, named their division series winners league co-champions.[69][70][71] The Miami FC versus San Francisco Deltas match on September 10 was canceled so the players and staff could prepare for the storm with their families.[72] The Orlando Pride of the National Women's Soccer League rescheduled their September 9 match to September 7.[73] Orlando City SC of Major League Soccer did not have any scheduled home games in September, but was unable to return to training facilities in Orlando due to Hurricane Irma.[74]

In college football, the UCF Knights-Memphis Tigers game scheduled for September 9 was moved to September 30, replacing UCF's game against Maine and Memphis game against Georgia State. UCF also canceled their game against Georgia Tech on September 16, as UCF's stadium hosted the National Guard.[75] The USF Bulls-Connecticut Huskies football game was also canceled. The Miami Hurricanes–Arkansas State Redwolves game scheduled for September 9 at Centennial Bank Stadium in Arkansas was canceled due to travel concerns for the University of Miami. The Florida Gators-Northern Colorado Bears match in Gainesville scheduled for September 9 was canceled. The Florida State Seminoles contest against the Louisiana–Monroe Warhawks was canceled on September 8.[76] The Seminoles' rivalry game with the Hurricanes in Tallahassee, originally scheduled for September 16, was postponed tp October 7. The FIU Panthers game against the Alcorn State Braves was moved up a day and relocated to Legion Field in Birmingham, Alabama.[77] The Georgia Southern Eagles game against the New Hampshire Wildcats on September 9 was also moved to Legion Field for that day.[78]

FEMA funding

As of September 5, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funding was running dangerously low, due to its response to Hurricane Harvey in Texas the previous week, prompting the Trump administration to request an immediate $8 billion in additional funding as Irma approached Florida.[79] Given the rate that current funds are being consumed and the catastrophic damage, the United States Senate almost doubled the requested amount to $15.3 billion, with the understanding that this would only be about 10% of what will be required for responding to Harvey.[80]

Impact

| Territory | Fatalities | Damage (2017 USD) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla (UK) | 1 | $290 million | [6][81] |

| Bahamas | 0 | $135 million | [82] |

| Barbados | 1 | — | [6] |

| Barbuda (AG) | 3 | $150 million | [6] |

| British Virgin Islands (UK) | 4 | $3.6 billion | [6][83] |

| Cuba | 10 | $13.2 billion | [84] |

| Haiti | 1 | — | [6] |

| Puerto Rico (U.S.) | 3[nb 2] | $1 billion | [6][85] |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 0 | $45 million | [81] |

| Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy (FR) | 11 | $4.17 billion | [86] |

| Sint Maarten (NL) | 4 | $2.98 billion | [87] |

| Turks and Caicos Islands (UK) | 0 | $500 million | [6] |

| United States | 92[nb 2] | $50 billion | [6][88] |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 4[nb 2] | $1.1 billion | [89] |

| Totals: | 134 | $77.2 billion |

Caribbean

Hurricane Irma's path was such that its impact was both far-reaching and devastating, with landfalls in Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Martin, the Bahamas, Cuba, and the United States, all at major hurricane intensity. Furthermore, the size of the storm system meant that destruction was prevalent even in territories well removed from landfall occurrences. Irma is the second-costliest Caribbean hurricane on record, after Maria.[90]

Antigua and Barbuda

The eyewall of the hurricane moved over Barbuda near its record peak intensity early on September 6; a weather station observed a wind gust of 160 mph (260 km/h). The same station also recorded a minimum barometric pressure of 916.1 mbar (27.05 inHg).[6] The exact state of the island remained unclear for hours after Irma's passage, as downed phone lines ceased all communication with nearby islands.[14] Later that afternoon, Prime Minister Gaston Browne surveyed the territory by helicopter, revealing an effectively uninhabitable island. Irma damaged or destroyed 95% of the structures on Barbuda, including its hospital, schools, and both of its hotels;[91] it completely flattened some residential blocks while submerging others.[92][93] The destruction rendered the island's sole airport and much of its infrastructure inoperative—including water and telecommunication services—which further hampered relief efforts. Property damage on Barbuda ranged from $150 million to $300 million. A total of three storm-related deaths were reported on the island.[6]

In addition to the catastrophic impact on Barbuda's human residents, concern turned to the storm's effects on the island's wildlife. The island's only endemic bird, the near-threatened Barbuda warbler, numbered less than 2,000 individuals prior to the hurricane. For some time it was unknown if the warbler survived the hurricane or its aftermath; however within a few months it was confirmed that not only did the species survive, but most of the birds survived the storm.[94] Barbuda's Codrington Lagoon, home to the largest colony of magnificent frigatebirds in the Caribbean, with an estimated 2,500 nesting pairs, was also inundated by the storm surge.[95]

Remaining just outside of Irma's strongest windfield, Antigua sustained less severe damage, in the form of leveled roofs and fences, downed power poles and lines, and uprooted trees. Some street flooding also took place in low-lying areas.[96] Three people were treated for minor storm-related injuries.[97] Forensic disaster analysts from the Center for Disaster Management and Risk Reduction Technology (CEDIM), a Germany-based risk management agency, estimate that economic losses for Antigua and Barbuda will exceed $120 million.[81]

Saint Martin

On the morning of September 6, Irma's center crossed the island of Saint Martin while the storm was at peak intensity, sweeping away entire structures, submerging roads and cars, and triggering an island-wide blackout.[98] Irma's extreme winds ripped trees out of the ground and sent vehicles and debris from damaged structures scattered across the territory. On the French side of Saint-Martin, entire marinas around Marigot were left in ruins, littered with the stranded remnants of boats that had smashed into each other.[99] A hotel caught on fire, but dangerous conditions and impassable roads prevented firefighters from putting out the blaze. Another hotel lost nearly all of its ground floor.[100] Media images depicted devastated room interiors with furniture hurled around after the winds had shattered their windows.[99] Irma killed four people on the French side of the island and injured 50 others, one of whom was in critical condition. As many as 95% of the buildings there were damaged to some degree; 60% of those were totally uninhabitable.[101] Estimates from CEDIM indicate a minimum of $950 million worth of economic losses.[81] Total losses exceeded €3.5 billion (US$4.17 billion).[86]

A similar situation unfolded in Sint Maarten, Saint Martin's Dutch half, as intense winds ripped through buildings and lifted vehicles aloft "as if they were matches".[102] The hurricane wreaked havoc on Princess Juliana International Airport, with "huge chunks of the building [strewn] across the runway and a jet bridge snapped in half."[103] It demolished or severely damaged about 70% of Sint Maarten's houses, forcing thousands of residents into public shelters.[104] There were 4 deaths and 23 injuries,[6] 11 of which were serious, in the Dutch territory.[105] Irma is considered the worst natural disaster to hit Sint Maarten; the extent of its damage far exceeded that of any previous hurricane.[102] Total damages were estimated at €2.5 billion (US$2.98 billion).[87]

Saint Barthélemy

| Most intense landfalling Atlantic hurricanes Intensity is measured solely by central pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Landfall pressure |

| 1 | "Labor Day"[nb 3] | 1935 | 892 mbar (hPa) |

| 2 | Camille | 1969 | 900 mbar (hPa) |

| Gilbert | 1988 | ||

| 4 | Dean | 2007 | 905 mbar (hPa) |

| 5 | "Cuba" | 1924 | 910 mbar (hPa) |

| Dorian | 2019 | ||

| 7 | Janet | 1955 | 914 mbar (hPa) |

| Irma | 2017 | ||

| 9 | "Cuba" | 1932 | 918 mbar (hPa) |

| 10 | Michael | 2018 | 919 mbar (hPa) |

| Sources: HURDAT,[9] AOML/HRD,[10] NHC[107] | |||

Irma left widespread destruction and disastrous flooding along its path over the French island of Saint Barthélemy, southeast of Saint Martin. Describing the extent of the destruction, one local compared it to "a bomb that burned all vegetation," while another said that it were as if the hurricane had effectively "erased the island from the map".[108] Violent seas swept away entire coastal establishments, with one hotel being stripped of all but its foundation.[109] Streets in the capital of Gustavia were turned into rushing rivers, which carried away vehicles and pieces of furniture. The island's fire station was inundated with up to 6.4 ft (2.0 m) of flood waters.[109][110] With scores of homes and much of the infrastructure destroyed, the majority of the island's population was left stranded and without water, electricity or phone service.[108] The associated economic losses could exceed $480 million according to CEDIM's analysts.[81]

Preliminary assessments from the French government indicate that Hurricane Irma caused a combined €1.2 billion (US$1.43 billion) in insured losses across the French territories of Saint-Martin and Saint Barts. This total covered private property such as homes, vehicles and businesses (including lost revenue); the extent of the damage to infrastructural and public facilities remains undetermined. Nonetheless, this made Irma one of the costliest natural disasters to hit the French Republic in 50 years.[111]

On January 30, 2018, roughly five months after Irma, an analysis was published indicating that an anemometer on the island recorded an unofficial gust to 199 mph (320 km/h) before failing.[112]

Anguilla

The British Overseas Territory of Anguilla saw the eyewall of the storm pass over it on September 6. Many homes and schools were destroyed, and the island's only hospital was badly damaged.[6] The devastation was particularly severe in East End, where the winds uprooted scores of trees and power poles and demolished a number of houses. In The Valley, the island's capital, the hurricane blew out the windows of government buildings. Rough seas inflicted heavy damage upon several bays and harbors, and a seaside restaurant was completely eradicated.[113] About 90% of roads were left impassable.[6] The island's air traffic control tower was damaged, exacerbating the already poor communication with the island.[114] One death was reported on the island. Estimates of losses on the island total at least $190 million.[6]

Rest of the Lesser Antilles

Large swells ahead of Irma washed ashore debris and sea life in Castries, Saint Lucia, blocking some roads. Seaside roads were inundated with water.[115] One surfer was killed amid rough surf in Barbados after hitting a reef and breaking his neck. Trees were also destroyed.[116] The hurricane's effects, such as violent seas and rattling trees, were intense enough to be detected by seismographs in Guadeloupe. Several houses were damaged.[117] Around 8,000 households and a water supply network on that island lost power during the storm, leaving several communes in the dark without running water. Overall damage was limited to external parts of houses and trees that were blown onto roads and three unmanned ships wrecked by rough seas.[20]

Saint Kitts and Nevis endured similar conditions to other islands. Blustery rainstorms triggered scattered power outages and disabled the island's water system, but per the International Red Cross, the islands were spared the level of destruction seen elsewhere.[118] Still, Prime Minister Timothy Harris stated that property and infrastructure had sustained "significant damage."[31] The Dutch territories of Saba and Sint Eustatius were also struck by the hurricane's winds, resulting in infrastructural damage, water shortages and telecommunication outages.[113][119] Several houses were left uninhabitable. On Saba, the hurricane also defoliated trees and injured a few people.[113][119] CEDIM's analysts expect economic losses of $20–65 million for the two islands.[81]

British Virgin Islands

Damage in the British Virgin Islands was extensive. Numerous buildings and roads were destroyed on the island of Tortola, which bore the brunt of the hurricane's core. Four people were confirmed dead.[6] Along Cane Garden Bay, the storm surge submerged several seaside bars and a gas station. Satellite images revealed many of the island's residential zones had been left in ruins.[113] The hurricane passed over Necker Island, also causing severe damage and destroying the mansion of Richard Branson.[121]

Most homes and businesses were destroyed on the island of Jost Van Dyke, the smallest of the B.V.I.'s four main islands.[122] The Governor, Gus Jaspert, who had only been sworn into office 13 days previously, declared a state of emergency - the first time this has ever happened in the Territory.[123] After the storm, restoration of electricity took approximately 5 months.[124]

U.S. Virgin Islands

Irma's effects in the U.S. Virgin Islands were most profound on Saint Thomas, where at least 12 inches (300 mm) of rain fell, and on Saint John. Saint Thomas island suffered widespread structural damage, including to its police station and airport. Patients from the fourth and third floors of Charlotte Amalie's hospital had to be relocated to lower floors due to flooding from roof leaks. Three deaths were attributed to Irma on the island. On nearby Saint Croix, there were communication issues and some damage to the infrastructure.[113] Saint John lost access to ferry and cargo services, along with access to the local airport. Due to its normal reliance on electricity from Saint Thomas, the island was left without power.[125][126][127][128] Total damage from the three islands was at least $1.1 billion.

Puerto Rico

The hurricane passed north of Puerto Rico, but still caused significant damage to the United States territory. Along the coast, a tide gauge observed waves up to 1.5 ft (0.46 m) mean higher high water. Much of the main island experienced sustained tropical storm force winds, with a peak sustained wind speed of 55 mph (89 km/h) at a weather station along San Juan Bay, while the same site observed a peak wind gust of 74 mph (119 km/h).[6] However, on the island of Culebra, a wind gust of 111 mph (179 km/h) was reported.[129] Mainly due to strong winds, approximately 1.1 million out of 1.5 million of Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority's customers lost electricity.[130] Portions of Puerto Rico received heavy rainfall, with a peak total of 13.04 in (331 mm) in Bayamón,[6] causing seven rivers to reach flood stage, widespread flash flooding, and at least six landslides.[130]

The most severely affected areas included the offshore islands of Culebra and Vieques, as well as the northeastern, northern, and mountainous portions of the main island. On Culebra, the island suffered an almost complete loss of electrical and water services. At least 30 homes on the island were destroyed, while about 30 other experienced substantial damage. High winds also toppled a number of trees. The only telecommunications tower on Culebra sustained damage, cutting off outside communications for several hours.[130] In rural Loíza, 79 homes were destroyed.[131] Throughout Puerto Rico, 781 out of 1,600 telecommunications towers went out of commission, primarily due to power outages. At least 362,000 customers lost water services. Debris, mostly fallen trees, blocked at least 72 roads. Approximately 25% to 30% of banana, coffee, papaya, and plantain crops were damaged by strong winds, with losses to farmers estimated at $30.6 million.[130] Approximately 1,530 homes experienced at least moderate damage, with 1,448 homes moderately damaged, 32 extensively damaged, and 50 completely destroyed.[132]

Hurricane Irma was attributed to around $1 billion in damage,[85] and the NHC attributed three fatalities to Irma in Puerto Rico, though four deaths were related to the storm.[6][133] Two people died due to rainstorms ahead of the hurricane: one man died in Orocovis after falling off his ladder while repairing his roof; another man on the coast in Capitanejo died after being struck by lightning. Three nearby fishermen were burned by the same lightning strike, but survived. Two other people died during the hurricane: a woman died while being evacuated from her house in a wheelchair and fell, hitting her head; another person died in a car accident in Canóvanas.[134] Governor Ricardo Rosselló declared the islands of Culebra and Vieques to be disaster areas.[31]

Hispaniola

Although spared a direct hit, both the Dominican Republic and Haiti were affected by high winds and heavy rains. A bridge over the Dajabón River connecting the two countries was broken.[135]

In the Dominican Republic, the fishing community of Nagua sustained damage from waves that destroyed homes. 55,000 soldiers were deployed to affected areas to help with the cleanup efforts.[29] By the evening of September 7, the government had counted 2,721 damaged homes.[30]

In Haiti, flooding one meter deep sat in residential neighborhoods in places like Cap-Haïtien, Ouanaminthe, and Gonaives.[135] Mudslides, destroyed homes, flooded crops, and infrastructure damage were reported in the northern part of the country.[30] The total expanse of the flooding stretched from Môle-Saint-Nicolas in the west to the eastern border with the Dominican Republic.[136]

Turks and Caicos Islands

On the evening of September 7, at 7:30 p.m. AST (23:30 UTC), Hurricane Irma reached the Turks and Caicos Islands. While the eye passed just south of the main islands, crossing over South Caicos and the Ambergris Cays, the most powerful winds on the northern side of the eye swept all of the islands for more than two hours. Communications infrastructure was destroyed.[6]

On September 8, Minister of Infrastructure Goldray Ewing confirmed that damage to Providenciales was extensive, with the northwestern neighborhood of Blue Hill being "gone".[137] The hospital in the capital, Cockburn Town, was heavily damaged.[6] On South Caicos, 75% of roofs were lost.[138] Total damage was estimated at over $500 million.[6]

The Bahamas

In the Bahamas, the eye of the storm passed over Duncan Town, the major settlement of the Ragged Islands chain, on September 8. It also passed "almost directly over" Inagua and South Acklins, according to the Bahamas Department of Meteorology.[139]

Damages were largely confined to the southern islands starting the morning of September 8. On Mayaguana and Great Inagua, downed power lines knocked out communications.[140] On Great Inagua, 70% of homes sustained roof damage, and the island's school lost its roof entirely. The Morton Salt Company's signature production facility, one of the major employers in the country, experienced millions of dollars in damages.[141] The Acklins settlement of Salina Point was cut off from the rest of the island by flooding, while Crooked Island had widespread roof damage.[40] In the northern Bahamas, the worst property damage came on September 10 as the outer bands of the system produced tornadic activity on Grand Bahama and Bimini.[142][143] Damage and losses across The Bahamas amounted to $135 million.[82]

While Irma was making landfall in Florida, the ocean was drawn away from some western shorelines of the Bahamas due to strong easterly winds.[144]

Cuba

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Damage | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Irma | 2017 | $13.2 billion | [145] |

| 2 | Ike | 2008 | $7.3 billion | [146] |

| 3 | Matthew | 2016 | $2.58 billion | [147] |

| 4 | Gustav | 2008 | $2.1 billion | [146] |

| 5 | Michelle | 2001 | $2 billion | [148] |

| Sandy | 2012 | [149] | ||

| 7 | Dennis | 2005 | $1.5 billion | [150] |

| 8 | Ivan | 2004 | $1.2 billion | [151] |

| 9 | Charley | 2004 | $923 million | [151] |

| 10 | Wilma | 2005 | $700 million | [152] |

Early on September 9, Irma made landfall on the Camagüey Archipelago off the northern coast of Cuba, with sustained winds of 165 mph (266 km/h). The strongest official sustained wind speed was 124 mph (200 km/h), while the highest wind gust reached 159 mph (256 km/h); both were observed near Camila in Ciego de Ávila Province.[6] The weather station at Esmeralda, Camagüey, was damaged, with the wind gauge destroyed.[58] The north coast of Cuba experienced significant coastal flooding due to storm surge and abnormally high tides generated by the storm. Wave heights at Cayo Romano exceeded 26 ft (7.9 m). Storm surge penetrated as far as 1.2 mi (1.9 km) inland in some areas of Villa Clara Province. Multiple locations on the island observed at least 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall, with a peak total of 23.9 in (610 mm) of precipitation at Topes de Collantes.[6]

A total of 158,554 homes experienced some degree of damage, of which 14,657 were destroyed; approximately 1.9 million people experienced the direct effects of Irma.[154] The storm partially deroofed 103,691 homes, while 23,560 were completely deroofed. Irma damaged or destroyed 980 health facilities and 2,264 schools. Approximately 3.1 million people experienced disruptions to the water supply, while 246,707 people lost telephone service. About 334 mi (538 km) of roads were damaged. Crops also suffered extensively, with nearly 235,000 acres (95,000 ha) affected by the storm.[154] Throughout the country, the hurricane inflicted $13.185 billion in damage and killed 10 people, making Irma the costliest tropical cyclone in Cuban history.[84][155]

The tourist areas of Cayo Coco, Cayo Guillermo and Cayo Santa María and the nearby town of Caibarién received the brunt of the storm, with waves rolling through town and the characteristic one-story homes completely flooded. The storm most severely Ciego de Ávila and Villa Clara provinces. Flooding worsened as the hurricane moved west, pushing the storm surge along to the regions around Havana.[6] By the afternoon, limited flooding was occurring in Havana, including around the Malecón.[40] Portions of province coastal flooding surpassing that which was experienced during the Storm of the Century in 1993 and Hurricane Wilma in 2005.[6] In the city of Santa Clara, 39 buildings collapsed.[156] Rainfall resulted in several rivers reaching major flood stage. The town of Cabaiguán in Sancti Spíritus Province in particular suffered extensive inland flooding after the Zaza River swelled.[6]

Hurricane Irma directly affected a major colony of American flamingos on Cuba's northern Cayo Coco.[95] Early reports from Diario de Cuba indicated that several hundred flamingos had been killed by the storm, though other estimates ranged as high as several thousand birds.[95][157]

Mainland United States

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | $125 billion |

| 4 Harvey | 2017 | ||

| 3 | 4 Ian | 2022 | $113 billion |

| 4 | 4 Maria | 2017 | $90 billion |

| 5 | 4 Helene | 2024 | $89.2 billion |

| 6 | 3 Milton | 2024 | $85 billion |

| 7 | 4 Ida | 2021 | $75 billion |

| 8 | ET Sandy | 2012 | $65 billion |

| 9 | 4 Irma | 2017 | $52.1 billion |

| 10 | 2 Ike | 2008 | $30 billion |

Hurricane Irma affected multiple states in the South, especially Florida. Except for the Florida Keys, the total damage Irma caused was not as great as government officials and forecasters had warned. Irma weakened after making landfall in Cuba, but strengthened back into a Category 4 prior to hitting the Keys. The Florida Keys suffered the worst of the damage in the United States. After surveying the aftermath of Irma, Florida governor Rick Scott said "I thought we would see more damage" [on the mainland] but said "he witnessed devastation in the Keys".[161] President Donald Trump commented on Twitter that the devastation in some places was "far greater than anyone thought".[162]

Damage in the United States was estimated at a minimum of $50 billion. At the time, Irma was the fourth costliest tropical cyclone in the United States, behind hurricanes Sandy in 2012, Harvey earlier that year, and Katrina in 2005. However, later in September 2017, Hurricane Maria became the third costliest United States tropical cyclone, causing Irma to fall to the fifth costliest. At least 92 people, 10 directly and 82 indirectly, died throughout the United States in relation to Irma: 84 in Florida, 3 in Georgia, 3 in South Carolina, and 2 in North Carolina.[6]

Florida

Irma struck the state less than two weeks after Potential Tropical Cyclone Ten had caused the worst flooding seen in western Florida in 20 years, which further worsened the impacts in the region.[164][165][166][167] The storm's large wind field resulted in strong winds across much of Florida, except for the western Panhandle. The highest reported sustained wind speed was 112 mph (180 km/h) on Marco Island, while the strongest observed wind gust was 142 mph (229 km/h), recorded near Naples,[168] though wind gusts of 150 to 160 mph (240 to 260 km/h) likely occurred in the Middle Florida Keys.[169] More than 7.7 million homes and businesses in Florida were left without electricity at some point – approximately 73% of state.[170][171] Generally heavy amounts of rainfall were recorded to the east of the Irma's path, including a peak total of 21.66 in (550 mm) in Fort Pierce.[172] Heavy precipitation – and storm surge, in some instances – overflowed at least 32 rivers and creeks, causing significant flooding, particularly along the St. Johns River and its tributaries.[43] Many homes and businesses suffered damage or destruction, with more than 65,000 structures damaged to some degree in West Central and Southwest Florida alone.[46] Agriculture experienced about $2.5 billion in damage.[43] It was estimated that the cyclone caused at least $50 billion in damage, making Irma the costliest hurricane in Florida history, surpassing Hurricane Andrew, until it was itself surpassed by Hurricane Ian, 5 years later.[173]

Throughout Florida, at least 84 people died in storm-related incidents.[6] About half of the deaths occurred from drowning, trauma, and carbon monoxide poisoning.[174] Broward County had 21 fatalities, the most of any county in Florida. Among those deaths were 12 people at The Rehabilitation Center at Hollywood Hills, a Hollywood nursing home. The patients died from sweltering heat worsened by the lack of air conditioning.[174] The hurricane also left at least 14 deaths in Monroe County;[175] 6 deaths in Orange County; 5 deaths each in Duval, Miami-Dade, and Palm Beach counties; 4 deaths in both Highlands and Hillsborough counties; 3 deaths in both Marion and Polk counties;[174] 2 deaths each in Collier, Hardee, Leon, Pinellas, St. Lucie, and Taylor counties;[174][176][177] and 1 death in Hendry, Lake, Lee, Liberty, Manatee, Nassau, Okeechobee, Pasco, Seminole, St. Johns, and Volusia counties.[174]

With Irma making landfall in Monroe County as a Category 4 hurricane, the Florida Keys were hardest hit area in the state.[169] Strong winds and storm surge flooding caused major damage to buildings, trailer parks, boats, roads, the electricity supply, mobile phone coverage, internet access, sanitation, the water supply and the fuel supply throughout the island chain.[178][169] An estimated 10 ft (3 m) storm surge occurred at Cudjoe Key, where Irma made landfall.[179] Throughout the island, 625 homes sustained minor damage, 52 sustained major damage, and 81 were demolished. On Big Pine Key, one of the most devastated islands, 633 homes received minor impact, 299 homes received major impact, and 473 homes were completely destroyed. Overall in Monroe County, 27,649 homes experienced some degree of damage, including 1,179 homes being destroyed, 2,977 homes receiving major damage, and 5,361 suffering minor damage.[180]

After devastating the Keys, the storm then struck Collier County as a Category 3 hurricane. Several communities in the county suffered extensive damage, especially along the coast.[168] Throughout the unincorporated areas of the county, 65 homes, including 44 mobile homes, were demolished, while 1,008 homes received major damage. Property damages in unincorporated areas alone reach about $320 million.[181] Lee County was lashed by strong winds and heavy rainfall, which caused prolonged flooding in some areas.[182][183] More than 24,000 homes suffered some degree of damage, with almost 3,000 homes receiving major damage and 89 homes being destroyed.[184] Damage in the county totaled about $857 million.[185][46]

Impact in much of the Miami metropolitan area was generally limited to extensive tree and fence damage, as well as widespread power outages. However, in Miami-Dade County, about 1,000 homes received major damage and about 50% of crops were lost. Storm surge caused coastal flooding from Homestead to Downtown Miami, as well as in portions of Miami Beach.[168] Parts of the Florida Heartland were devastated by high winds and flooding, particularly Hendry and Highlands counties.[168][46] In the former, which has most citrus trees of any county in Florida, about 60% of orange crops were lost.[186] Throughout Hendry County, a total of 451 homes had minor damage, 131 homes suffered major damage, and 42 others were destroyed.[168] In Highlands County, 13,138 businesses and homes were damaged to some degree, with 144 being destroyed, 963 sustaining major damage, and 2,408 receiving minor damage. In Orange County, wind gusts reached 79 mph at Orlando International Airport. A wind gust of 91 mph was also recorded in Orlando at the top of the Disney Contemporary Resort.[187] Strong winds and heavy rainfall in Central Florida left some wind damage and flooding, necessitating evacuations and rescues, including more than 200 people in Orlo Vista after hundreds of homes were flooded.[46] A total of 2,999 business or homes were damaged in Lake County,[188] 7,430 in Seminole County, and 3,457 in Volusia County. Additionally, eight tornadoes touched down in Brevard County, all of which caused damage.[189]

Along much of the Gulf Coast of Florida, to the north of where Irma made landfall, negative storm surges were observed, with water retracting rather than pushing inland, causing little coastal flooding.[46] However, on the opposite coast, extensive erosion and storm surge flooding occurred in the First Coast, especially in Duval and St. Johns counties. In Duval County, the St. Johns River crested at heights that exceeded records set during Hurricane Dora in 1964. Portions of Jacksonville experienced flooding, particularly the downtown area and the Riverside and San Marco neighborhoods, with about 350 people rescued in those sections of the city. Water reached about 5 ft (1.5 m) high in some homes.[190] The city of Jacksonville suffered about $85 million in damage.[191]

In St. Johns County, storm surge left extensive damage to oceanfront properties in Ponte Vedra Beach and Vilano Beach, with several becoming uninhabitable.[192][193] Additionally, some riverfront businesses in St. Augustine's historic district were flooded due to storm surge from the Matanzas River.[194] In nearby Clay County, rainfall and storm surge combined to cause extensive flooding along portions of the Black Creek and the St. Johns River, with record high crests at several locations along the former.[190] About 350 people and 75 animals were rescued from floodwaters throughout the county. A total of 275 homes were destroyed, 175 were inflicted major damage, and 124 received minor damage.[195]

Other states

Three deaths were reported in Georgia due to falling trees and debris, along with widespread wind damage and power outages throughout the state primarily due to fallen trees.[196] On Tybee Island, as well as St. Simons Island the storm surge caused extensive flooding.[197][198] The tropical storm also did $54 million in damage in the state.[199]

In Charleston, South Carolina, the third highest storm surge on record was recorded, reaching a height of approximately 10 ft (3 m).[200] By of September 12, almost 100,000 had lost power in Upstate South Carolina.[201] Five people died in storm-related incidents across South Carolina, all from indirect incidents.[202] The tropical storm caused damages totaling $500,000 in the state.[203]

Light damage occurred in other areas, including Tennessee.[204] About 75,000 customers in North Carolina lost power due to Irma, where two fatalities occurred. [6][205] The storm also caused $600,000 in damages in Alabama.[206]

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Irma's path through the West Indies and Caribbean, the devastation to roads, harbors and airports significantly impeded the transportation and distribution of relief supplies. Foreign countries moved to provide much of the initial aid. The British, Dutch, French, and United States governments sent warships and planes with supplies and manpower to the region.[29][207] International leaders, including Dutch King Willem-Alexander and French President Emmanuel Macron, quickly moved to visit affected territories.[208][209]

Some of the affected countries and territories also offered assistance to each other. Cuba, which sustained extensive damage from the storm, sent 750 health workers to Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, The Bahamas, Dominica, and Haiti.[210] Government officials and members of the public in Puerto Rico delivered assistance and evacuated people stranded on other islands. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services granted special 30-day humanitarian visas for British Virgin Islanders to stay in Puerto Rico.[211] Hundreds of people stranded on Saint Martin were flown to the Dominican Republic on humanitarian grounds.[212]

Antigua and Barbuda

In response to Hurricane Jose's approach, the Government of Antigua and Barbuda issued a mandatory evacuation on September 9 for any remaining residents on Barbuda. A Miami cargo plane landed on Antigua later that day, carrying over 60 tons (120,000 lbs) of relief supplies for the displaced storm victims—including bottled water, canned food and power generators.[213]

British Overseas Territories

RFA Mounts Bay stationed itself near Anguilla and provided support and relief work to the island with its helicopters and 40 marines and army engineers.[214] The ship delivered 6 tonnes of emergency aid to Anguilla and army engineers repaired a fuel leak at Anguilla's main petrol dump, restored power to the island's hospital and provided shelters for those left homeless by the hurricane.[215][216] The ship arrived in the British Virgin Islands on September 8, 2017, to provide emergency relief to the islands, including providing shelters, food and water.[215] HMS Ocean was diverted from the Mediterranean to provide relief from Gibraltar to the affected British Overseas Territories of Anguilla, British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos on September 7,[217] and aid was also supplied by the Department for International Development from their disaster response center at Kemble Airfield. As part of a £32 million operation named Operation Ruman, nearly 500 UK military personnel with emergency relief were dispatched from RAF Brize Norton.[218] This included the first deployment of No. 38 Expeditionary Air Wing with three RAF aircraft: two Airbus A400M Atlas and one C-130J Hercules to support relief efforts.

The British government also drafted two members of the UK police cadre into the region on September 10, and 53 police officers were drafted from RAF Brize Norton to the affected British Overseas Territories on September 15 to help maintain order.[219][220] UK politicians, including the chairs of the foreign affairs and development select committees, criticized both the government's preparations for the storm and its response as inadequate.[221][222]

By September 12, the Department for International Development had delivered more than 40 tonnes of aid into the region, including into Turks and Caicos, and 1,000 UK military troops were deployed in the region as part of relief efforts.[216] The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Theresa May, pledged an additional £25 million worth of funding as part of relief efforts in the region on September 13, 2017, and the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Boris Johnson, said that a further 250 UK military personnel would be deployed into the area within the next few days.[223] Anguilla's Chief Minister, Victor Banks, praised the British government's response to the storm and said that Boris Johnson's visit to the island "sends a very positive signal to Anguillans that the British are serious about their response to this very severe hurricane", but went on to say that the current financial commitment from the UK was not substantial enough.[223][224]

By September 15, the United Kingdom had over 70 military personnel and 4 police officers in Anguilla and had delivered 15 tonnes of aid to the island.[225] In the British Virgin Islands, Royal Marines had cleared the airfield so that it was operational for the delivery of aid into the islands, with more than 200 British military personnel and 54 UK police officers on the ground and 8 tonnes of aid delivered to the islands.[225] 120 British military personnel were on the ground in Turks and Caicos, and over 150 shelter kits and 720 liters of water were delivered to the islands on September 15.[225]

Amendments to international aid rules by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (or OECD) allowed for the UK government to provide access to £13 billion worth of aid to the affected British Overseas Territories, through the UK's Official Development Assistance (ODA) by November 2017.[226]

The Bahamas

By the afternoon of September 9, Bahamas Power and Light Company had dispatched crews across the archipelago to repair infrastructure damage. The southernmost islands, which were most severely affected by Irma's eye, remained largely inaccessible for days.[227] Assessments showed that 15% of the national telecommunications network had been affected, with at least one tower destroyed.[228] Bahamasair resumed a limited domestic schedule on September 10, with international flights still canceled due to existing and anticipated destruction at other destinations.[229]

The worst devastation occurred on Ragged Island, over which Irma's eye had directly passed. After days of the National Emergency Management Agency not being able to physically reach the island, officials were finally able to inspect it; they promptly declared it uninhabitable.[230][231] Prime Minister Hubert Minnis said that it was the worst disaster area he or his officials had ever seen, and that all remaining residents would need to leave, potentially permanently.[230][232] Business leaders and other officials called for a new long-term development model to shift the population away from such sparsely-settled islands.[233]

On Grand Bahama and Bimini, where tornadoes associated with Irma touched down on September 10, more than 100 people were left displaced. Infrastructure damage included docks, parks, and the power system.[143]

Aside from tangible asset losses, Irma brought significant economic damages. International freight shipping was projected to be offline for a week, and costs for rebuilding supplies were inflated due to demand in the U.S.[234]

Cuba

Swollen rivers contributed to worsening flooding in the days after the storm system left, resulting in additional evacuations. Officials resorted to using inflatable rafts to access affected areas. The national electrical infrastructure was said to be extensively damaged.[156]

Hispaniola

In the Dominican Republic, flooding worsened following Irma's departure, leading the number of displaced persons to increase to more than 24,000 by September 8. President Danilo Medina ordered further evacuations due to at-risk dams, while the government banned swimming in rivers and ordered boats kept in port.[235] More than 422,000 people were left without water due to 28 aqueducts being damaged.[236]

In Haiti, officials stated that losses were greater than they could have been since people largely did not heed early preparation and evacuation warnings.[30] At least 5,000 homes were flooded. One man died trying to cross a flooded river; another went missing and 17 were injured.[237] The trash- and waste-contaminated floodwaters in places like Cap-Haïtien, Ouanaminthe, and Gonaives led to fears of cholera outbreaks.[135] Flooding continued to worsen days after the storm, as runoff from the mountains swelled rivers in low-lying farming communities. United Nations peacekeepers from Brazil were able to gain access to the flooded northwest region to provide urgent aid, but non-governmental organizations and Haitian economists warned that the estimated 30,000 victims would need longer-term assistance as well. Prime Minister Jack Guy Lafontant appointed a government commission to address Irma's effects, with Action Against Hunger in charge of humanitarian coordination.[136]

United States territories

In the USVI, residents and tourists alike were described as being in a state of traumatic shock.[156] By September 7, the USS Wasp amphibious assault ship had arrived in the USVI to provide supplies, damage assessment, and evacuation assistance. Four additional warships, some of which had already been on their way to Texas to assist with Hurricane Harvey relief, were redirected to the region.[207] At a September 10 news conference, Governor Kenneth Mapp described Irma as a "horrific disaster" for which "[t]here will be no restorations or solutions in days or weeks." The Federal Emergency Management Agency airlifted in goods for residents, who were subjected to a curfew. Norwegian Cruise Lines and Royal Caribbean Cruise Line agreed to transport tourists to Florida, contingent upon port availability following the state's own experience with Irma.[238]

On Saint John, described as "perhaps the site of Irma's worst devastation on American soil," it took six days for an active-theater disaster zone to be established, leading to criticism of the U.S. government response.[239] The National Guard was delayed in reaching Saint John due to the number of overturned boats left in the harbor.[240] The National Guard was brought in to maintain order, while the Coast Guard brought evacuees to cruise ships bound for San Juan and Miami.[239] There was still no electricity on St. John in the middle of October 2017.[241]

By September 9, more than one million Puerto Ricans were still without power, tens of thousands were without water, and several thousand were still in shelters. Hospitals were operating on generator power. The government was struggling to establish contact with the islands of Culebra and Vieques.[31] By September 10, the main island had recovered enough to serve as a refuge for people stranded on other islands, including 1,200 tourists from Saint Martin and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Airlifts had brought more than 50 patients to Puerto Rico.[211]

Five months after Irma, two-thirds of the hospital beds on Saint Thomas were still unavailable, due to extensive physical damage and staffing shortages.[242]

Saint Martin and French Overseas Department

Damage to Sint Maarten's harbor and to Princess Juliana International Airport left the Dutch part of Saint Martin unreachable, although the smaller Grand Case-Espérance Airport on the French side could be reopened by September 7 for supply aid by helicopter and airplane.[243] The French armed forces based in Guadeloupe and French Guiana flew equipment and troops on board a CASA/IPTN CN-235 aircraft.

The following day, the Dutch military was able to airlift dialysis patients off the island while also dropping leaflets to warn islanders about the rapidly approaching Hurricane Jose.[58] Although the airport was closed, 435 students and faculty of the American University of the Caribbean were evacuated by the U.S. military.[244] On September 10, Dutch King Willem-Alexander departed for the region, with intentions to visit Sint Maarten and other affected Dutch territories and commonwealth members.[208]

French President Emmanuel Macron followed this announcement by stating his intentions to visit the French part of the island on September 12 in order to bring aid supplies. In response to criticism of the French handling of the disaster, 1,000 troops, police, and other emergency workers were sent to Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy.[209]

On both sides of Saint Martin, desperate conditions combined with food and water shortages in Irma's aftermath led to reports of violence, scavenging, and theft. In response, the French government increased its troop deployment to 2,200 and the Dutch government sent more than 600 military and police personnel.[221][245]

The day after the hurricane hit Saint Barthelemy the French armed forces based in Guadeloupe and French Guiana flew equipment and troops into the reopened Grand Case-Espérance Airport. On September 7 and 9, equipment and personnel were flown from France to Guadeloupe and Martinique.[246]

Florida

Sporadic reports of looting and burglaries at several Miami Metro area businesses occurred with the theft of non-essential items such as sports apparel and athletic shoes during the height of the storm.[247][248]

On September 11, Florida Governor Rick Scott conducted an aerial tour to survey the damage to the Keys. The Overseas Highway remained closed while authorities assessed the integrity of the 42 bridges along the route.[249] Residents returning to the Keys were faced with a police roadblock, to the south of Florida City.[250] USS Iwo Jima, USS New York and aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln were sent to the Keys area to aid with the recovery.[251]

On September 12, some residents were allowed to return into the Keys as far as Islamorada. Although road damage blocked entry any farther than Islamorada, bridges had been inspected and found safe to Sugarloaf Key.[252] By late on September 12, the Overseas Highway had been repaired and the bridges inspected as safe for first responders to travel to Key West.[253] On September 16, residents were free to return to Marathon.[254] Residents were allowed to return to Key West the following day, although the Keys remained closed to tourists and a checkpoint remained in place in Florida City.[255]

Due mainly to the widespread loss of power, cell phone service was also reduced after battery backup power for cell phone towers ran out and backup generators ran out of fuel.[256][257][258] In an impact report by the FCC, as of 11 AM EDT on September 12, 89 of 108 (82%) cell phone towers were non-functioning in Monroe County (Florida Keys), 154 of 212 (73%) were non-functioning in Collier County (Naples), 36 of 46 (78%) were non-functioning in Hendry County, and an additional six counties had 41-60% of cell phone towers not functioning, including Lee County (Fort Myers) and Miami-Dade County.[259]

NOAA released map-format aerial reconnaissance image data of damage from the storm. The imagery featured several areas of Florida: including the Florida Keys, the southwest coast of Florida from Marco Island to Punta Gorda, much of the northeast coast of Florida, and portions of the Jacksonville area. Portions of the Georgia and South Carolina coasts were also photographed.[260] Additionally, the Sun-Sentinel published before and after photos of several landmarks in the Florida Keys.[261]

In the days after the hurricane, due to the heavy rainfall, numerous rivers had flooded, including residential areas.[262] Public health risks, such as diarrheal infections and mosquito-borne illnesses, remain from the flooding that resulted in the aftermath of the hurricane. A large concern from flooding is contamination because people become exposed to dirty floodwaters and the potential for contaminated water to enter the local water supply is significant. One example of an illness that can enter the water supply is leptospirosis, which is rat urine carries into the floodwaters. Untreated exposure to leptospirosis can cause kidney damage, meningitis, and liver failure. Noroviruses and other infections are also a risk.[263]

Following Irma's passage, a 15 ft (4.6 m) hand-carved wooden canoe was discovered on the banks of the Indian River and could be several hundred years old. The state has removed the canoe for examination and safe keeping.[264]

Due to Irma's and Hurricane Harvey's impact in Florida and Texas, U.S. employment declined in September 2017 for the first time since September 2010. The leisure and hospitality industries were especially hard hit, losing 111,000 jobs in September.[265]

Records

Irma set multiple records for intensity, especially at easterly longitudes, time spent at such an intensity, and its intensity at landfall. When Irma reached Category 5 intensity with winds of 175 mph (282 km/h) at 11:45 UTC on September 5 at 57.7°W,[6] it became the easternmost Atlantic hurricane of this strength on record, surpassing Hurricane David of 1979, later beaten by Hurricane Lorenzo 2 years later.[266] By 00:15 UTC on September 6, Irma reached peak intensity with 180 mph (285 km/h) winds and a minimum pressure of 914 mbar (914 hPa; 27.0 inHg). This ties it with Hurricane Mitch of 1998, Hurricane Rita of 2005, and Hurricane Milton of 2024 as the sixth-strongest Atlantic hurricane by wind speed. Only five other Atlantic hurricanes have been recorded with wind speeds higher than Irma: Hurricane Allen of 1980, which had maximum sustained winds of 190 mph (310 km/h), and the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, Hurricane Gilbert of 1988, Hurricane Wilma of 2005, and Hurricane Dorian of 2019, all of which had peak winds of 185 mph (298 km/h).[267] At the time, Irma was also the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic Ocean outside the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico; later surpassed by Hurricane Dorian,[268] and was the strongest Atlantic hurricane since Wilma in terms of maximum sustained winds, and the most intense in terms of pressure since Dean in 2007.[269] In addition, Irma achieved one of the longest durations of Category 5 strength winds,[6] and the third-highest accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for a tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin, with a value of 64.9 units. Only the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane and Hurricane Ivan in 2004 achieved higher values.[270][271]

On September 6, Irma made landfall on the islands of Barbuda, Saint Martin, and Virgin Gorda at peak strength. This ties Irma with cyclones Monica of 2006 and Winston of 2016, and typhoons Zeb of 1998 and Megi of 2010 as the seventh-strongest tropical cyclone to make landfall globally – in terms of sustained winds – trailing only Typhoon Goni of 2020 which bore winds of 195 mph (314 km/h) at landfall, Typhoon Haiyan of 2013 and Typhoon Meranti of 2016, which bore winds of 190 mph (310 km/h) at landfall, and the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, Typhoon Joan of 1959, and Hurricane Dorian of 2019, which bore winds of 185 mph (298 km/h) at landfall.[272][273] Irma is second to the 1935 Labor Day hurricane and Hurricane Dorian of 2019 as the strongest landfalling cyclone on record in the Atlantic basin, and is the first hurricane to make landfall anywhere in the Atlantic at Category 5 status since Felix in 2007.[274] Irma is the first recorded Category 5 hurricane to affect the northern Leeward Islands, and was one of the worst storms to hit the region on record, along with Hurricane Donna in 1960 and Hurricane Luis in 1995. In addition, Irma is only the second hurricane on record to make landfall in Cuba at Category 5 intensity, with the other being a hurricane in 1924.[269] Furthermore, when Irma made landfall on Barbuda, Saint Martin, Virgin Gorda, and Cuba as a Category 5 hurricane, it became one of only two recorded Atlantic storms to make landfall in multiple nations at this strength; the other was Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which struck both Eleuthera and the United States as a Category 5 hurricane.[275]

Irma made landfall in the Florida Keys with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) and a pressure of 931 mbar (931 hPa; 27.5 inHg), making it the strongest hurricane to strike Florida in terms of wind speed since Charley in 2004, and the most intense to strike the state in terms of barometric pressure since Andrew in 1992. In the span of two weeks, two Category 4 hurricanes—Harvey and Irma—struck the continental United States, the first time on record two Atlantic tropical cyclones of such strength made landfall on the country in the same hurricane season.[276][277] This also marked only the third occurrence of two consecutive Atlantic storms making landfall in the United States as major hurricanes. The other two instances were the Great Charleston and Cheniere Caminada hurricanes in 1893, and hurricanes Ivan and Jeanne in 2004.[270]

Retirement

Because of the extensive damage and loss of life the hurricane caused in the northeastern Caribbean and the United States, particularly in Florida, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Irma from its rotating naming lists in April 2018; it will never again be used for another Atlantic hurricane. It was replaced with Idalia for the 2023 season.[278]

See also

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Cuba hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes (2000-present)

- 1928 Okeechobee hurricane – a hurricane that hit similar areas

- Hurricane Donna (1960) – took a similar track to Irma until landfall in Florida

- Hurricane Hugo (1989) – a Category 5 hurricane which also formed east of the Lesser Antilles

- Hurricane Matthew (2016) – caused damage and deaths in Haiti, before moving to The Bahamas and then skimming the coastline of Florida, before moving up the coast

- Hurricane Eta (2020) – made landfall in Florida twice three years later

- Hurricane Ian (2022) – made landfall in Florida five years later as a high-end Category 4 hurricane

- Hurricane Helene (2024) – made landfall in the Big Bend as a Category 4 hurricane that also affected the Appalachian Mountains

- Hurricane Milton (2024) – another Category 5 hurricane which made landfall in Florida as a Category 3 hurricane seven years later; also prompted the largest evacuation in the state since Irma

- Hurricane Oscar (2024) – a smaller and weaker hurricane which had a similar track to Irma until it reached Cuba

- Operation RUMAN – UK military-civil disaster relief response to Hurricane Irma.

- Tropical cyclones in 2017

- Weather of 2017

Notes

- ^ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale.[2]

- ^ a b c Irma caused 82 indirect and 10 direct deaths in the U.S., 3 direct deaths in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and 3 indirect deaths in Puerto Rico.

- ^ Storms with quotations are officially unnamed. Tropical storms and hurricanes were not named before the year 1950.[106]

- ^ The storm category color indicates the intensity of the hurricane when landfalling in the U.S.

References

- ^ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HUDRAT version 2)". United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- ^ Christopher W. Landsea (June 2, 2011). "A: Basic Definitions". In Neal M. Dorst (ed.). Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. A3) What is a super-typhoon? What is a major hurricane ? What is an intense hurricane ?. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Irmageddon: Thousands of Miamians Just Had Their First Taste of Hurricane Misery". Miami New Times. September 13, 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Amy Gesenhues (December 13, 2017). "Hurricane Irma was the No. 1 top trending Google search in the US & globally for 2017". Search Engine Land. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.