History of Havana

Havana | |

|---|---|

| San Cristóbal de la Habana | |

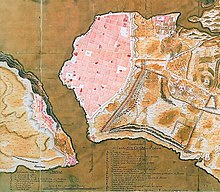

Map of the city and harbour of Havana in 1740 |

Havana was founded in the sixteenth century displacing Santiago de Cuba as the island's most important city when it became a major port for Atlantic shipping, particularly the Spanish treasure fleet.[1]

History

[edit]Founding of Havana

[edit]

Havana was first visited by Spaniards during Sebastián de Ocampo's circumnavigation of the island in 1508.[2] In 1510, the first Spanish colonists arrived from the island of Hispaniola and began the conquest of Cuba. Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded San Cristóbal de la Habana in 1514, on the southern coast of the island, near the present town of Surgidero de Batabanó, or more likely on the banks of the Mayabeque River close to Playa Mayabeque. All attempts to found a city on Cuba's south coast failed, however, an early map of Cuba drawn in 1514 places the town at the mouth of this river.[3][4](in Spanish). Between 1514 and 1519, the city had two different establishments on the north coast, one of them in La Chorrera, today in the neighborhood of Puentes Grandes, next to the Almendares River. Havana's present location is adjacent to what was then called Puerto de Carenas, in 1519. The quality of this natural bay, now the site of Havana's harbor, warranted this change of location. Bartolomé de las Casas wrote:

...one of the ships, or both, had the need of careening, which is to renew or mend the parts that travel under the water, and to put tar and wax in them, and entered the port we now call Havana, and there they careened so the port was called de Carenas. This bay is very good and can host many ships, which I visited few years after the Discovery... few are in Spain, or elsewhere in the world, that are their equal...[2]

This superb harbor at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico with easy access to the Gulf Stream, the main ocean current that navigators followed when traveling from the Americas to Europe, led to Havana's early development as the principal port of Spain's New World colonies. This final establishment is commemorated by El Templete.

Havana was the sixth town founded by the Spanish on the island, called San Cristóbal de la Habana by Pánfilo de Narváez: the name combines San Cristóbal, patron saint of Havana, and Habana, of obscure origin, possibly derived from Habaguanex, a Native American chief who controlled that area, as mentioned by Diego Velasquez in his report to the king of Spain. Shortly after the founding of Cuba's first cities, the island served as little more than a base for expeditions of exploration, conquest, and settlement of other lands. Hernán Cortés organized his expedition to Mexico from the island. Cuba, during the first years of the Discovery, provided no immediate wealth to the conquistadores, as it was poor in gold, silver and precious stones, and many of its settlers moved to the more promising lands of Mexico and South America that were being discovered and colonized at the time. The legends of Eldorado and the Seven Cities of Gold attracted many adventurers from Spain, and also from the adjacent colonies, leaving Havana and the rest of Cuba largely unpopulated.

Pirates and the Spanish Treasure Fleet

[edit]

Havana was originally a trading port, and suffered regular attacks by buccaneers, pirates, and French corsairs. The first attack and resultant burning of the city was by the French corsair Jacques de Sores in 1555. The pirate took Havana easily, plundering the city and burning much of it to the ground. De Sores left without obtaining the enormous wealth he was hoping to find in Havana. Such attacks convinced the Spanish Crown to fund the construction of the first fortresses in the main cities — not only to counteract the pirates and corsairs, but also to exert more control over commerce with the West Indies, and to limit the extensive contrabando (black market) that had arisen due to the trade restrictions imposed by the Casa de Contratación of Seville (the crown-controlled trading house that held a monopoly on New World trade).

To counteract pirate attacks on galleon convoys headed for Spain while loaded with New World treasures, the Spanish crown decided to protect its ships by concentrating them in one large fleet, the Spanish treasure fleet, which would traverse the Atlantic Ocean as a group. A single merchant fleet could more easily be protected by the Spanish Armada or Navy. Following a royal decree in 1561, all ships headed for Spain were required to assemble this fleet in the Havana Bay. Ships arrived from May through August, waiting for the best weather conditions, and together, the fleet departed Havana for Spain by September.

This naturally boosted commerce and development of the adjacent city of Havana (a humble villa at the time). Goods traded in Havana included gold, silver, alpaca wool from the Andes, emeralds from Colombia, mahoganies from Cuba and Guatemala, leather from the Guajira, spices, sticks of dye from Campeche, corn, manioc, and cocoa. Ships from all over the New World carried products first to Havana, in order to be taken by the fleet to Spain. The thousands of ships gathered in the city's bay also fueled Havana's agriculture and manufacture, since they had to be supplied with food, water, and other products needed to traverse the ocean. In 1563, the Capitán General (the Spanish Governor of the island) moved his residence from Santiago de Cuba to Havana, by reason of that city's newly gained wealth and importance, thus unofficially sanctioning its status as capital of the island.

On December 20, 1592, King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City (ciudad). Later on, the city would be officially designated as "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies" by the Spanish crown. In the meantime, efforts to build or improve the defensive infrastructures of the city continued. The San Salvador de la Punta castle guarded the west entrance of the bay, while the Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro guarded the eastern entrance. The Castillo de la Real Fuerza defended the city's center, and doubled as the Governor's residence until a more comfortable palace was built. Two other defensive towers, La Chorrera and San Lázaro were also built in this period..

17th–18th centuries

[edit]

Havana expanded greatly in the 17th century. New buildings were constructed from the most abundant materials of the island, mainly wood, combining various Iberian architectural styles, as well as borrowing profusely from Canarian characteristics. During this period the city also built civic monuments and religious constructions. The convent of St Augustin, El Morro Castle, the chapel of the Humilladero, the fountain of Dorotea de la Luna in La Chorrera, the church of the Holy Angel, the hospital de San Lazaro, the monastery of Santa Teresa and the convent of San Felipe Neri were completed in this era.

In 1649 a fatal epidemic, brought from Cartagena in Colombia, affected a third of the population of Havana. On November 30, 1665, Queen Mariana of Austria, widow of King Philip IV of Spain, ratified the heraldic shield of Cuba, which took as its symbolic motifs the first three castles of Havana: the Real Fuerza, the Tres Santos Reyes Magos del Morro and San Salvador de la Punta. The shield also displayed a symbolic golden key to represent the title "Key to the Gulf". On 1674, the works for the City Walls were started, as part of the fortification efforts. They would be completed by 1740.

By the middle of the 18th century Havana had more than seventy thousand inhabitants, and was the third-largest city in the Americas, ranking behind Lima and Mexico City but ahead of Boston and New York.[5]

British occupation

[edit]Siege of Havana (1762)

The city was captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The episode began on June 6, 1762, when at dawn, a British fleet, comprising more than 50 ships and a combined force of over 11,000 men of the Royal Navy and Army, sailed into Cuban waters and made an amphibious landing east of Havana.[6] The British seized the heights known as La Punta on the east side of the harbor and commenced a bombardment of nearby El Morro Castle, as well as the city itself. After a two-month siege,[7] El Morro was attacked and taken, only after the death of the brave defender Luis Vicente de Velasco e Isla, on 30 July 1762. The city formally surrendered on 13 August.[6] It was subsequently governed by Sir George Keppel on behalf of Great Britain. Although the British only lost 560 men to combat injuries during the siege, more than half their forces ultimately died due to illness, yellow fever in particular.[8]

The British immediately opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society.[7][8] Though Havana, which had become the third largest city in the new world, was to enter an era of sustained development and strengthening ties with North America, the British occupation was not to last. Pressure from London by sugar merchants fearing a decline in sugar prices forced a series of negotiations with the Spanish over colonial territories. Less than a year after Havana was seized, the Treaty of Paris (1763) was signed by the three warring powers thus ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida in exchange for the city of Havana on the recommendation of the French, who advised that declining the offer could result in Spain losing Mexico and much of the South American mainland to the British.[7]

After regaining the city, the Spanish transformed Havana into the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Construction began on what was to become the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the biggest Spanish fortification in the New World. The work extended for eleven years and was enormously costly, but on completion the fort was considered an unassailable bastion and essential to Havana's defence. It was provided with a large number of cannons forged in Barcelona. Other fortifications were constructed, as well: the castle of Atarés defended the Shipyard in the inner bay, while the castle of El Príncipe guarded the city from the west. Several cannon batteries located along the bay's canal (among them the San Nazario and Doce Apóstoles batteries) ensured that no place in the harbor remained undefended.

The Havana Cathedral was constructed in 1748 as a Jesuit church, and converted in 1777 into the Parroquial Mayor church, after the Suppression of the Jesuits in Spanish territory in 1767. In 1788, it formally became a cathedral. Between 1789 and 1790 Cuba was apportioned into an individual diocese by the Roman Catholic Church. On January 15, 1796, the remains of Christopher Columbus were transported to the island from Santo Domingo. They rested here until 1898, when they were transferred to Seville's cathedral, after Spain's loss of Cuba.

Havana's shipyard (named El Arsenal) was extremely active, thanks to the lumber resources available in the vicinity of the city. The Santísima Trinidad was the largest warship of her time. Launched in 1769, she was about 62 metres (203 ft) long, had three decks and 120 cannons. She was later upgraded to as many as 144 cannons and four decks. She sank following the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. This ship cost 40,000 pesos fuertes of the time, which gives an idea of the importance of the Arsenal, by comparing its cost to the 26 million pesos fuertes and 109 ships produced during the Arsenal's existence.[9]

19th century

[edit]

As trade between Caribbean and North American states increased in the early 19th century, Havana became a flourishing and fashionable city. Havana's theaters featured the most distinguished actors of the age, and prosperity amongst the burgeoning middle-class led to expensive new classical mansions being erected. During this period Havana became known as the Paris of the Antilles.

The 19th century opened with the arrival in Havana of Alexander von Humboldt, who was impressed by the vitality of the port. In 1837, the first railroad was constructed, a 51 km stretch between Havana and Bejucal, which was used for transporting sugar from the Valle de Güines to the harbor. With this, Cuba became the fifth country in the world to have a railroad, and the first Spanish-speaking country. Throughout the century, Havana was enriched by the construction of additional cultural facilities, such as the Tacon Teatre, one of the most luxurious in the world, the Artistic and Literary Liceo (Lyceum) and the theater Coliseo (Colosseum). The fact that slavery was legal in Cuba until 1886 led to interest from the American South, including a plan by the Knights of the Golden Circle to create a 'Golden Circle' with a 1200 mile-radius centered on Havana. After the Confederate States of America were defeated in the American Civil War in 1865, many former slaveholders continued to run plantations by moving to Havana.[citation needed]

In 1863, the city walls were knocked down so that the metropolis could be enlarged. At the end of the century, the well-off classes moved to the quarter of Vedado. Later, they emigrated towards Miramar, and today, evermore to the west, they have settled in Siboney. At the end of the 19th century, Havana witnessed the final moments of Spanish colonialism in America, which ended definitively when the United States warship Maine exploded and sank in its port, giving that country the pretext to invade the island. The 20th century began with Havana, and therefore Cuba, under occupation by the USA. In 1906 the Bank of Nova Scotia opened the first branch in Havana, Cuba. By 1931 it had three branches in Havana.

Republican period and post-revolution

[edit]

During the Republican Period, from 1902 to 1959, the city saw a new era of development. All endeavors of industry and commerce grew very rapidly. Cuba recovered from the devastation of war to become a well-off country, with the third largest middle class in the hemisphere, and Havana, the Capital of the country, became known as the Paris of the Caribbean. Construction was an important industry. Apartment buildings to accommodate the new middle class, as well as mansions for the Cuban tycoons, were built at a fast pace. Numerous luxury hotels, casinos and nightclubs were constructed during the 1930s to serve Havana's burgeoning tourist industry, strongly rivaling Miami. In the thirties, organized crime characters were not unaware of Havana's nightclub and casino life, and they made their inroads in the city. Santo Trafficante, Jr. took the roulette wheel at the Sans Souci, Meyer Lansky directed the Hotel Habana Riviera, with Lucky Luciano at the Hotel Nacional Casino. The Havana Hilton owned by the Hospitality Workers Retirement Fund was Latin America's tallest, largest hotel. At the time, Havana became an exotic capital of appeal and numerous activities ranging from marinas, grand prix car racing, musical shows and parks.

The development and opportunity offered by Cuba in general, and Havana in particular, made the island a magnet for immigration. Cuba received millions of immigrants during the Republic. It received so many Spaniards that, today, it is estimated that one quarter of the Cuban population descends from Spanish immigrants.

Havana achieved the title of being the Latin American city with the biggest middle class population per-capita, simultaneously accompanied by gambling and corruption where gangsters and stars were known to mix socially. During this era, Havana was generally producing more revenue than Las Vegas, Nevada. A gallery of black and white portraits from the era still adorn the walls of the bar at the Hotel National, including pictures of Frank Sinatra with Ava Gardner, Marlene Dietrich and Gary Cooper. In 1958, about 300,000 American tourists visited the city. One of the most well-known visitors and resident to the area was the American author Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), who quoted, "In terms of beauty, only Venice and Paris surpassed Havana". Hemingway wrote several of his famous novels in Cuba and lived there the last 22 years of his life.[10] Havana had 135 cinemas at that time – more than Paris or New York City.[11]

After the revolution of 1959, the new government promised to improve social services, public housing, and official buildings; nevertheless, shortages that affected Cuba after Castro's abrupt expropriation of all private property and industry under a strong communist model backed by the Soviet Union followed by the U.S. embargo, hit Havana especially hard. As a result, today much of Havana is in a dilapidated state. By 1966–68, the Cuban government had nationalized all privately owned business entities in Cuba, down to "certain kinds of small retail forms of commerce" (law No. 1076[12]). Most of these laws and economic restrictions still remain today.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, its subsidies to Cuba ended, costing the Cuban government billions of dollars, and causing a severe economic downturn. During this time of the 1990s that came to be known as the Special Period, Havana's communist government survived, but the worsening economic situation was illustrated by a change in a favorite joke: soon after Fidel Castro had come to power in 1959, the joke went, signs in the Havana Zoo were changed from "Please do not feed the animals" to "Please do not take the animals' food". During the Special Period, some people joked the signs were again changed, now begging visitors not to eat the animals.[13][14] Indeed, the peacocks, the buffalo and even the rhea reportedly disappeared from the Havana zoo.[14]

After 50 years of prohibition, the communist government increasingly turned to tourism for new financial revenue, and has allowed foreign investors to build new hotels and develop hospitality industry. Paradoxically, while foreign investment is welcome, Cubans are forbidden to participate. The Cuban population is only allowed to work as cooks, gardeners and taxi-drivers, but not to become owners or investors of any property. For these reason among others, the tourism industry during the socialist revolution has failed to generate the projected revenues. After a decline in the early 2000s, Cuban tourism hit an all-time high of 2.7 billion dollars (USD) in 2008.[15] In Old Havana, effort has also gone into rebuilding for tourist purposes, and a number of streets and squares have been rehabilitated.[16] But Old Havana is a large city, and the restoration efforts concentrate in all but less than 10% of its area.

In 2022, at least 40 people were killed by an explosion at the Hotel Saratoga.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Alejandro de la Fuente, Havana and the Atlantic in the Sixteenth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 2008.

- ^ (in Spanish) Fundación de La Habana a orillas del Río Onicajinal o Mayabeque

- ^ San Cristobal de La Habana en el Sur

- ^ Thomas, Hugh: Cuba, A pursuit of freedom, 2nd Edition, p. 1.

- ^ a b Pocock, Tom: Battle for Empire: The very first world war 1756–63. Chapter Six.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Hugh: Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom 2nd edition. Chapter One

- ^ a b Gott, Richard (2004). Cuba: A new history. Yale University Press. pp. 39–41.

- ^ "Arquitextos – Periódico mensal de textos de arquitetura". Archived from the original on 2009-08-01. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ^ Ernest Hemingway life Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine – Homing To The Stream: Ernest Hemingway in Cuba.

- ^ "The Cuban revolution at 50: Heroic myth and prosaic failure". The Economist. December 30, 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Nigel Hunt. "Cuba Nationalization Laws". cuba heritage .org. Archived from the original on 2010-09-16. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Marjorie Sue Zatz. Producing Legality.

- ^ a b "Parrot diplomacy". The Economist. July 24, 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "Cuba tourism reached record levels in 2008". Usatoday.Com. 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ^ Old Havana restoration – Success on the restoration program of Havana