Barrio de San Lázaro, Havana

| Barrio de San Lázaro | |

|---|---|

Malecón, San Lázaro and Belascoáin: Vista Alegre Café, Hotel Manhattan by Purdy and Henderson, Engineers, La Casa de Beneficencia. ca 1951. | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Active |

| Type | Neighborhood |

| Location | Ward of Cayo Hueso, in the West of Centro Habana |

| Town or city | Havana |

| Country | Cuba |

Barrio de San Lázaro is one of the first neighbourhoods in Havana, Cuba. It initially occupied the area bounded by Calle Infanta to the west, Calle Zanja to the south, Calle Belascoáin to the east, and the Gulf of Mexico to the north, forming the western edge of Centro Habana. According to the 1855 Ordenanzas Municipales of the city of Havana, [1] Barrio San Lázaro was the Tercer Distrito (Third District) and was Barrio No. 8.[a] [1]

Caleta de San Lazaro

[edit]Arcabuco was the name of a footpath that began in Old Havana in the vicinity of the church of Loma del Ángel that ran in a westerly direction to an inlet cove that was 93 meters wide and approximately 5.5 meters in depth.[2] When Juan Guillén a Spanish soldier installed a carpentry shop to build small boats close to the cove the site became known as “La Caleta de Juan Guillén”, the road was known as “the caleta”.[3] Eventually the Hospital de San Lázaro, the Espada Cemetery, the San Dionisio mental asylum, and La Casa de Beneficencia were developed around the Caleta de San Lazaro.[citation needed]

Calle Belascoáin

[edit]

Calle Belascoáin is shown on the map of 1853 as the last street of the city.[2] Archived 2021-11-07 at the Wayback Machine The southern boundary of this area were the railroad tracks that lead to the Paradero de Villanueva and what eventually became Calle Zanja. This large territory is the Barrio de San Lázaro, a no man's land where the orphans from La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana, the lepers of the Hospital de San Lazaro, the mentally ill from Casa de Dementes de San Dionisio and the deceased of the Espada Cemetery were located.[citation needed]

Calle San Lázaro

[edit]

Calle San Lázaro, perpendicular to Calle Belascoáin, is 25 blocks long and extends from the steps of the University of Havana in the west to almost the Castillo San Salvador de la Punta in the east. Since the opening of the Espada cemetery in 1806, Calle San Lazaro was used for funeral processions to the cemetery. The street did not become populated until 1815. Calle San Lázaro owes the origin of its name to the Hospital de San Lázaro which was founded in 1746. First, it was called Calle Ancha del Norte and later, El Basurero (trash dump), later still, Antonio Maceo Avenue, and then Avenida de la República. In 1936 the City of Havana Council restored its original name to Calle San Lázaro.

The backs of the houses originally faced onto the sea; the boardwalk was not built until the beginning of the 20th century. Much earlier, the famous sea baths called La Punta, del Recreo and de Beneficencia were built. In the 19th century, the only important building on the road was the Beneficencia, built-in 1794, and where the Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital stands today. 14 blocks of San Lázaro, facing the Malecón, are a priority area for conservation, where the Office of the City Historian is carrying out a rehabilitation program for the historically valuable buildings located in the area.[4]

Torreón de San Lázaro

[edit]

The Torreón is a cylinder, a round tower of masonry. It is approximately 4.57 metres (15.0 ft) in diameter and 9.14 metres (30.0 ft) high with embrasures along its wall at the intermediate level and a battlement parapet at the third level roof.[3] Archived 2020-02-07 at the Wayback Machine It has a wooden entry door at ground level. With the passage of time, the San Lazaro cove was filled and the tower was included in a Republican-era park named after Major General Antonio Maceo. In an 1853 map of Havana it is shown as the Torreón de Vijias (lookouts).[5] In 1982, the Torreón was inscribed along with other historic sites in Old Havana on the UNESCO World Heritage List, because of the city's importance in the European conquest of the New World and its unique architecture.[6]

Located in the Parque Antonio Maceo at Malecón and Calle Marina in present-day central Havana is the Torreón de San Lázaro, a watchtower built-in 1665 by the engineer Marcos Lucio. From this fortification a lookout could warn military forces by way of torches of threats of attack by corsairs and pirates. In this regard, it served as a link in the defense chain between the Batería de la Reina, La Punta, and the Santa Clara Battery located at the site of today's Hotel Nacional.[7]

The Torreón de San Lázaro is named for the nearby leprosarium at the Hospital de San Lázaro which was near the cove formerly known as the Cove of Juan Guillén.

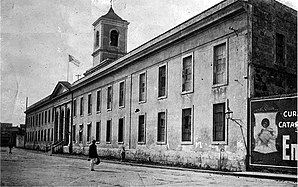

La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad

[edit]In 1794 La Casa de Beneficencia, located on land located in front of the San Lázaro cove, an area known at that time as the Betancourt Garden, was the initiative of a group of illustrious Habaneros, including Luis de Peñalver, the Bishop of New Orleans, the Countess de Jaruco, the Marquise of Peñalver and Cárdenas, and the Captain-General, Luis de las Casas. Initially, La Casa de Beneficencia admitted only females.

The financial situation of La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad was difficult, sometimes distressing. Towards 1824, General Francisco Dionisio Vives took it out of its financial quagmire by providing a tax on lottery tickets and another on the cockfights that took place in the trenches of the Castillo de la Fuerza.

In 1914, President Mario García Menocal converted La Casa de Beneficencia into a state institution and provided it, without forgoing donations and popular collections, with a budget for maintenance. In the 19th century in what is now Maceo Park the Batería de la Reina was installed. Along Calle Belascoaín, at the back of the building and shown on an 1866 map, was the bullring of Havana.[8] On Calles Virtudes and Concordia, was the jai alai frontón.

In the late 1950s, the Batista government bought the building and demolished it with the intention of building the headquarters of the National Bank of Cuba.[9] In a speech, Fidel Castro states: "We have always seen a building under construction here. This building (bank building) is an inheritance. We inherited this building at the time of the victory of the revolution. A building for the national bank was being built."[10] However, a photograph published in Havana in January 1959 showing Castro's son Fidelito riding on top of a tank contradicts this statement as the Beneficiensa building can be seen on the left background of the photo.

Hospital San Lázaro

[edit]The Hospital de San Lázaro dates back to the seventeenth century when it served as a headquarters for some temporary huts for those suffering from leprosy built near the Caleta de San Lázaro, a natural inlet that was located about a mile outside the city walls. The chaplain of the church, presbyter Juan Pérez de Silva, and Dr. Francisco Teneza in view of the deplorable conditions of the leprosy patients sought the help of the King of Spain Felipe V.[citation needed] The Real Hospital de San Lázaro was built near the Juan Guillén Cove in 1781 and the church inside a two-story courtyard which became a pilgrimage frequented by those suffering from leprosy and followers of San Lázaro or Babalú Ayé seeking spiritual solace.[11]

The site of San Lázaro Hospital was on Calle Aramburu between Calles Jovellar and San Lázaro. The hospital was close to the Espada Cemetery, the San Dionisio mental asylum, and La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana, and all were close to the Caleta de Juan Guillén which was filled in during the initial construction of the Malecon in 1901. The quarry of San Lazaro where Jose Marti had been imprisoned in 1870, was to the west of Calle Principe. The former location of La Casa de Beneficencia is the current location of Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital. The site today encompasses Cayo Hueso which is a consejo popular (ward) in the municipality of Centro Habana. A traditionally working-class neighborhood populated by Afro-Cubans, it is known for its many cultural landmarks such as the Callejón de Hamel, the Fragua Martiana Museum and the Parque de los Mártires Universitarios. Cayo Hueso formed part of Barrio San Lázaro, an area bounded by Calle Infanta to the west, Calle Zanja to the south, Calle Belascoáin to the east and the Gulf of Mexico to the north. Cayo Hueso was declared a barrio on 26 July 1912 and made part of Centro Habana upon its establishment in 1963.

Espada Cemetery

[edit]

It was the custom of the people of Havana to bury the dead in a crypt inside of the churches, placing them according to their social rank and prices paid for the vault. (e.g. Cathedral of Havana and Iglesia del Espíritu Santo.)

The Espada cemetery was a garden type. A single wall contained the crypts. The design and construction were directed by an architect with the surname of Aulet. The cemetery had a central courtyard; the walls were approximately 6 meters tall (4 crypts) with an elaborate stone coping for protection from the rain. The paintings that adorned the entrance pavilion were by the Venetian Giuseppe Perovani (1765–1835). The cemetery was officially inaugurated on February 2, 1806. Only a small section of the original wall remains.

The Espada Cemetery was outside the jurisdiction of the church, built under the authority of the government of Don Salvador De Muro and Salazar, Marquis of Someruelos, who ordered that the General Cemetery of Havana be built between the Calles of San Lázaro, Vapor, Aramburu, and Espada. This public work was helped by the Bishop Juan José Díaz de Espada and Fernández de Landa under the auspices of the Governor, the City Council, and the Cathedral of Havana. The cemetery was located a mile west outside the walls of the City and near the cove of San Lazaro.[12]

After being officially called the General Cemetery of Havana and Campo Santo (Holy Field), it was renamed the Espada Cemetery in honor of the Bishop of Espada y Landa, whose hand was decisive for its establishment. The cemetery and the relocation of the corpses from the various churches were carried out by three black slaves with carts pulled by horses and financed with Bishop of Espada y Landa's own wealth.

The first remains taken to the new cemetery were those of the former Captain General Don Diego Manrique, which were exhumed from the church of San Francisco de Asís; as well as those of the Bishop of Milaza, José González Cándamo, who was governor of the miter of Havana, and who had been exhumed from Havana Cathedral. The bodies were gathered at the chapel of the Casa de Beneficencia. The corpses were transferred in black velvet boxes distinguished with gold trimmings.[13]

Casa de Dementes de San Dionisio

[edit]The Casa de Dementes, inaugurated on September 1, 1828, and intended exclusively for males, was located on San Lázaro Street, between the Hospital de San Lázaro and the Cemetery de Espada, on lots that had served to bury the individuals deceased in the old hospital of San Juan de Dios.[4] Until then, these patients had been housed in the Maternity Home.[14]

Cirilo Villaverde—author of a short story about the Hill of Taganana and of the novel Cecilia Valdés—writes on a visit to Casa de Dementes de San Dionisio: "The entrance door, is precisely in the middle, under the porch, on the sides of which open four windows with strong iron bars, which give light and air to other rooms occupied by the doctor, the house butler, and two soldiers and a corporal, who do not stand guard but are of respect, in case of need. On the threshold of the aforementioned door, on a marble tombstone, with golden letters of relief, this inscription reads:

TO HUMANITY

TO THE HEALTHY JUDGMENT

Mens Sana in Corpore Sano.

Francisco Dionisio Vives Juan José Espada

GOVERNOR BISHOP, YEAR 1827"[15]

Diario de la Marina (27 July 1947) published what Conde San Juan de Jaruco in the 19th century wrote:

"The House (for the) Insane of San Dionisio was one of the great works of charity that realized in Havana, at the expense of a voluntary subscription, the lieutenant general don Francisco Dionisio Vives y Planes, captain general and governor of the Island of Cuba. This establishment was inaugurated, destined exclusively for people of the masculine sex, the 1 of September of 1828, in the street of San Lazaro, between the hospital of this name and the cemetery De Espada, in some lots that had served to bury the individuals deceased in the old hospital of San Juan de Dios. Until then, the insane had been housed in Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad. (#3 on the map: "locos.").

On March 3, 1901, the Jai Alai frontón was inaugurated on a plot of land bounded by the Calles Concordia y Lucena.[5] [16] The Basques (/bɑːsks/ or /bæsks/; Basque: euskaldunak [eus̺kaldunak]; Spanish: vascos [ˈbaskos]; French: basques [bask]) are a European ethnic group,[17][18][19] characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians.[20][21][22] Basques are indigenous to and primarily inhabit an area traditionally known as the Basque Country (Basque: Euskal Herria), a region that is located around the western end of the Pyrenees on the coast of the Bay of Biscay and straddles parts of north-central Spain and south-western France.[21] They exported the game from ca. 1800 to all parts of the world including the Americas. Jai alai (/ˈhaɪ.əlaɪ/: [ˈxai aˈlai]) is normally played with a ball that is bounced off of the floor and three walls accelerated to high speeds with a wicker hand-held device called a (Cesta). A sport played in Spain, southwest of France and Latin American countries, it is a variation of Basque pelota, a term, coined by Serafin Baroja in 1875, is also often loosely applied to the fronton (the open-walled playing area) where the sport is played. The game is called "zesta-punta" (basket tip) in Basque. There was a Jai alai court [6] in the back of La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana near Calle Belascoain, the edge between the city and the countryside.[23] The fronton was called "the palace of the screams " (Spanish: palacio de los gritos). All activity in the fronton was stopped by the new revolutionary government in Januiuary 1, 1959 and the building today is in a high level of disrepair. [7]

Rules and customs

[edit]The site of the court at Concordia and Lucernas was 140 ft × 227.5 ft. The court for jai alai consists of walls on the front, back, and left, and the floor between them. If the ball (called a pelota, "ball" in Standard Basque) touches the floor outside these walls, it is considered out of bounds. Similarly, there is also a border on the lower 3 feet (0.9 m) of the front wall that is also out of bounds. The ceiling on the court is usually very high, so the ball has a more predictable path. The court is divided by 14 parallel lines going horizontally across the court, with line #1 closest to the front wall and line #14 the back wall. In doubles, each team consists of a frontcourt player and a backcourt player. The game begins when the frontcourt player of the first team serves the ball to the second team. The winner of each point stays on the court to meet the next team in rotation. Losers go to the end of the line to await another turn on the court. The first team to score 7 points (or 9 in Superfecta games) wins. The next highest scores are awarded "place" (second) and "show" (third) positions, respectively. Playoffs decide tied scores.

A jai alai game is played in round robin format, usually between eight teams of two players each or eight single players. The first team to score 7 or 9 points wins the game. Two of the eight teams are in the court for each point. The server on one team must bounce the ball behind the serving line, then with the Cesta "basket" hurl it towards the front wall so it bounces from there to between lines 4 and 7 on the floor. The ball is then in play. The ball used in jai alai is handcrafted and consists of metal strands tightly wound together and then wrapped in goatskin. Teams alternate catching the ball in their (also handcrafted) Cesta and throwing it "in one fluid motion" without holding or juggling it. The ball must be caught either on the fly or after bouncing once on the floor.

Cuban Grand Prix

[edit]

The Cuban Grand Prix was a sports car motor race held for a brief period in the late 1950s in Havana, Cuba, last raced in 1960. The 1958 race is best remembered as the backdrop to the kidnapping of Formula One World Champion driver Juan Manuel Fangio by anti-government rebels linked to the 26th of July Movement.[24] There is an exclusive report in the newspaper Zig Zag by the man who allegedly kidnapped Fangio and a note by Fangio.[25]

The race was established in 1957 as Fulgencio Batista envisioned creating an event to attract tourists, particularly from the United States. A street circuit was established on the Malecon. The first race was a success; it was won by Fangio driving a Maserati 300S, leading home Carroll Shelby driving a Ferrari 410 S and Alfonso de Portago in a Ferrari 860 Monza.

The following year the official Maserati team arrived in force with their fleet of Maserati 300S cars and Fangio and Stirling Moss as drivers. On the eve of the race, Fangio was abducted from his hotel by an armed man.[24] The Cuban government ordered the race to continue. Moss and Masten Gregory led the race which was red-flagged after just six laps. Armando Garcia Cifuentes had crashed his Ferrari into the crowd, killing seven.[26]

The 1959 race was cancelled as Fidel Castro's revolution entered its final stages. The race returned in 1960, at a new venue on service roads around a military airfield. Moss, driving a Maserati Birdcage for privateer team Camoradi, had a comfortable victory over NART run Ferrari 250 TR59 driven by Pedro Rodríguez with Masten Gregory third in a Porsche 718.[27]

Quarry of San Lázaro

[edit]

Arrested at the age of 16, José Martí was sentenced to six years of imprisonment of hard labor in the San Lazaro Quarry in the western part of the Barrio, where he was sent to cut coral rock. It is now a memorial called Fragua Martiana,[8] in reference to the role it played in forging Martí's character. Since its inauguration in 1952, it's been the place that marks the end of the March of the Torches; Every year on the eve of January 28, people from Havana, mainly university students, march from the University of Havana to the Fragua Martiana to celebrate Martí's birthday. The march, held for the first time in 1953 (the 100th anniversary), was first organized by the Federation of University Students and has become an important tradition in Cuban university life.[28]

On April 5, 1870, José Martí was confined to the quarries of San Lázaro, sentenced to forced labor for multiple reasons which included crimes of infidelity. Marti was 17 years old and shackled to the ankle of his right leg and his waist. A few months earlier, in October 1869, a group of Spanish volunteers had searched the home of Martí's friend, Fermín Valdés Domínguez, and found a letter addressed to an acquaintance, whom they had accused of being a traitor for entering the Spanish army. Both claimed to be the author of the letter, both were imprisoned. Martí was sentenced to six years of imprisonment on April 4, 1870. He entered the jail in Havana where he would work up to twelve hours a day under difficult conditions.

He met Nicolás del Castillo and Lino Figueredo, and his experiences under confinement served as material for the book 'The Political Prison in Cuba'.[29] In this booklet, José Martí tells in a masterly way the bitter experience lived in the quarries of San Lazaro during the period in which he was imprisoned, forced to work in subhuman conditions.[30] It is addressed to the Spaniards as if he were speaking to them as if presenting this horrible spectacle for scenes; continually invokes them to see and condemn. Martí was not looking for literary novelty; he conceived it as a document of indignant accusation, not only for physical abuse but for the mistreatment of morals and the human condition; but that does not stop being an artistic piece. Faced with the terrible experience pain of presidio served as a testimony in his work:

"The notion of good floats above all, and is never engulfed".

("La noción del bien flota sobre todo, y no naufraga jamás".)

By mid-August, due to the bad state of health, José Martí was transferred to the cigar store of the prison and then to La Cabaña. The lime in the quarry had hurt his eyes, the pressure of the shackle had produced an ulcer on his leg. On 28 August 1870 in dedication to his mother, Leonor Perez Cabrera, written in a photo in which it appears of foot and with the shackle, and he writes:

"Look at me, mother, and in the name of love do not cry: if a slave of my age and my doctrines, your martyr heart filled with thorns, think that they are born among the thorns, flowers."

[b] Spanish Jose Marti.[31]

Antonio Maceo

[edit]The 1916 statue of General Antonio Maceo by the Italian sculptor Doménico Boni and subsequent park, La Casa de Beneficencia, the hotel Manhattan on Calle Belascoáin, by the U.S. Engineering firm of Purdy and Henderson, and the Hotel Vista Alegre also at the beginning of Calle Belascoáin, anchored a geographically important corner close to the sea of the large expanse of land known as El Barrio San Lazaro and within it and immediately to the north was the Caleta de San Lazaro.[32] Cayo Hueso was also a part of El Barrio de San Lazaro. Cayo Hueso ("bone cay"), its name derives from its location near the Espada Cemetery.[33] it was demolished in 1908. Among the oldest institutions in the area were the leprosy hospital (demolished in 1916), the Casa de Beneficencia orphanage (currently the Hermanos Ameijeiras hospital).[34] Buildings in the Barrio San Lazaro that were important to the early development of the city were the Hospital de San Dionisio for the mentally insane, the Cementerio General known as the Campo Santo and more commonly referred to as the Espada Cemetery was the precursor to the Colon Cemetery, and a room for the treatment of the mentally ill located on the side of the Real Casa de Beneficencia on Calle Belascoáin. The monument to Antonio Maceo was located near a place previously occupied by the Batería de la Reina, (1861), located in front of the La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad, at the intersection of Belascoaín and San Lázaro. In 1916 the monument was placed but the park was not built, many voices were raised in a protest demanding that a greater tribute be paid to the figure of Antonio Maceo.

The Casa de Beneficencia eventually reached from Calles San Lazaro and Belascoáin to Marquez Gonzalez and Virtudes where the jai alai fronton was located.[35] A former orphan described the place: "Beneficencia had two gates; the front that overlooked San Lázaro street with a large garden. The right part of that building (facing north), corresponded to the chapel that was always open to the public. To the left of the main entrance were the school offices followed by the barbershop and other workshops. The students were never in those gardens where there was only the possibility of visual contact with them. The other gate that served as access to the vehicles only was in the back of the school; that is, on Virtudes Street between Belascoaín and Lucena. On the right (always facing north), part of the building was located dedicated to the classrooms and on its left was the hospital... This magnificent school was converted into a barracks... they took us out of there to turn it into the Antonio Maceo military school."[36]

Batería de Santa Clara

[edit]

The battery was named after Juan Procopio Bassecourt, the Count of Santa Clara, governor of Cuba who built it between 1797 and 1799, the Santa Clara Battery is west of the Canteras de San Lázaro and was part of a system of colonial fortifications of the city. The site is shown on the map of 1900 and is today part of the gardens of the Hotel Nacional de Cuba.

The Battery of Santa Clara artillery had 20 pieces of large caliber, long-range Ordóñez guns some of which can still be seen today in the gardens of the Hotel Nacional.[7] From this same point, many British ships were fired upon during the siege of Havana, a military action that took place from March to August 1762.[c]

The protected area is a long and solid parapet of 193 meters in length and about 80 meters from the sea. Its fire had to cross with the one of the Castillo San Salvador de la Punta, dominating the cove of Juan Guillén.

In 1890, the Battery of Santa Clara was reinforced with 1.60 metre thick walls of Portland cement concrete. It was the first time Portland cement had been used on the island. The Battery of Santa Clara was declared by UNESCO in 1982, together with the historic center of Old Havana, a World Heritage Site. Of this defensive system, two cannons are currently exhibited in the garden: the "Krupp" and the "Ordóñez", the latter being the largest cannon in the world at the time.[citation needed]

The first battery on this site was built between 1797 and 1799 and was named for Juan Procopio Bassecourt y Bryas, Count of Santa Clara, the Spanish governor of Cuba from 1796 to 1799. The battery was modernized in 1895, when it received new guns. It was armed with three 11" Krupp and two 12" Ordóñez guns, as well as two Nordenfelt 6-pounder quick firing guns for close-in defense. There were also some leftover older, obsolete pieces, including eight 8" howitzers,[37] which may have been 210mm (8.3") sunchado howitzers.

On 7 May 1898, during the Spanish–American War, the Spanish lured the USS Vicksburg and the US Revenue Cutter Morrill into chasing a Spanish schooner under the guns of the battery. The battery fired too soon on the US vessels, which were able to escape without taking a hit.[38] Then on 13 June the Krupp gun fired on the protected (armored) cruiser USS Montgomery at a range of 9000 meters,[39] also without effect.

Following the Spanish–American War, US troops were billeted there and later a barracks was constructed, which was torn down in 1928 or 1929 to provide a site for the hotel.

Hill of Taganana

[edit]The Santa Clara Battery was built on top of a hill that was home to one of the most historic caves on the island. The hill of Taganana, located in the coastal outcrop of Punta Brava near the cove of San Lázaro took its name from a cavern in the Canary Islands where the princess Guanche Cathaysa took refuge. She was captured and sold by the Castilians as a slave in 1494. The 7-year-old Guanche girl from Taganana (in Santa Cruz de Tenerife) was taken captive along with four other youngsters (Cathayta, Inopona, Cherohisa, and Ithaisa). Cathayta was sold as a slave with her companions in Valencia, in April 1494. It is believed that after this she spent the rest of her life somewhere in Spain as a Menina for some woman of the Spanish high society.[40]

In Cuba, a parallel legend states that one of the caves under the Taganana hill served as a shelter for a Cuban Indian girl of the same name who fled from her Spanish persecutors. [9]

The Cuban novelist Cirilo Villaverde immortalized Guanche Cathaysa in his literary work, La Cueva de Taganana.[41]

Arnoldo Varona writes:

The hill of Taganana, as it is known, is located in the coastal outcrop of Punta Brava, almost to the extreme of the cove of San Lázaro, and was a habitual place of pirate landings, that took its name of another cavern in the island Canaria of Tenerife where the princess Guanche Cathaysa took refuge when she escaped after she was captured and sold by the Castilians as a slave in 1494.

Gallery

[edit]-

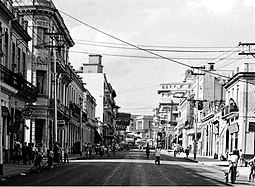

Calle San Lázaro, Havana

-

Map of Habana in 1853

-

Map of Habana in 1866

-

Hospital de San Lázaro

-

Batería de la de la reina demolition

-

La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad during the hurricane of 1919.

-

La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana from Belascoáin y Malecón 1940s

-

Barrio de San Lázaro. Vista Alegre Cafe. ca 1940.

-

Neon signs at Calle Belascoain seen from Maceo Park

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Barrio núm; 8. „San Lázaro." — Está limitado por la costa de San Lázaro, desde la calzada de la Beneficencia, hasta la batería de Sta. Clara; por la vereda que desde allí se dirige al puente de la Zanja en la calzada. do: ta bffanta; y por ésta hasta el ferro-carril, por la linea do ést^ haeita^bL calzada d^ la Beneficencia y por ésta hasta el mar.

- ^ "Mírame, madre, y por amor no llores: si esclavo de mi edad y mis doctrinas, tu mártir corazón llené de espinas, piensa que nacen entre las espinas, flores.”

- ^ The siege of Havana was a military action from March to August 1762, as part of the Seven Years' War. British forces besieged and captured the city of Havana, which at the time was an important Spanish naval base in the Caribbean, and dealt a serious blow to the Spanish Navy. Havana was subsequently returned to Spain under the 1763 Treaty of Paris that formally ended the war.

References

[edit]- ^ Ordenanzas municipales de la ciudad de La Habana. Imprenta del Gobierno y Capitanía General. 1855. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- ^ "MALECON – BATERIA DE LA REINA". Facebook. Retrieved 2021-11-06.

- ^ "Calle de San Lázaro". 4 February 2019. Retrieved 2021-11-06.

- ^ "La calle San Lázaro, crisol de revolucionarios antes y ahora". Archived from the original on 2018-12-06. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ Plano pintoresco de La Habana [circular reference]

- ^ "Old Havana and its Fortification System". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Forts of Cuba". Archived from the original on 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- ^ Plano de La Habana [circular reference]

- ^ "Castro Inaugurates Centro Habana Hospital". Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- ^ "Ameijeiras speech". Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Santuario Nacional de San Lázaro". Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ "El Cementerio de Espada". Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- ^ "El Cementerio Espada: Primer cementerio de Latinoamérica fuera de una iglesia". Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- ^ "Casa de Dementes de San Dionisio". Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ^ "Casa de San Dionisio". 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-12-28. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "Un Jai-Alai en ruinas en el corazón de La Habana". 30 July 2016. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ "Basque". Britannica Online for Kids. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "Basque". Oxford Reference online. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ Totoricaguena, Gloria Pilar (2004). Identity, Culture, and Politics in the Basque Diaspora. University of Nevada Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-87417-547-9. Retrieved 3 November 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Günther, Torsten; et al. (2015). "Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (38): 11917–11922. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11211917G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509851112. PMC 4586848. PMID 26351665.

- ^ a b Olalde, Iñigo; et al. (2019). "The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years". Science. 363 (6432): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2019Sci...363.1230O. doi:10.1126/science.aav4040. PMC 6436108. PMID 30872528.

- ^ Bycroft, Clare; et al. (2019). "Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 551. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..551B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w. PMC 6358624. PMID 30710075.

- ^ Numa, Lázaro. "Andar tras las huellas de Tacón". Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- ^ a b Laurence Edmondson (20 July 2010). "Kidnapped in Cuba". ESPN F1. ESPN. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Yo Secuestre a Juan Manuel Fangio". Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ "A Grand Prix in Havana?". grandprix.com. 24 November 1997. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Stirling Moss Race History: 1960 Cuban Grand Prix". stirlingmoss.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Jose Marti Tour of Havana". 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-13.

- ^ "The José Martí Timeline". Archived from the original on 2018-11-01. Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- ^ "chronology of events in Jose Marti's life" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ "La Llave del Golfo". 5 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ "Café Vista Alegre en Habana de otros tiempos". Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2018-11-03.

- ^ Baker, Christopher P. (2015). Moon Havana. Berkeley, CA: Avalon Travel. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9781631212833. Archived from the original on 2018-12-03. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Franco, José L. (1975). Antonio Maceo: apuntes para una historia de su vida, Tomo I (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Ciencias Sociales. p. 268.

- ^ "Havana Jai Alai: 1904". Archived from the original on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ "LA CASA DE BENEFICENCIA Y MATERNIDAD DE LA HABANA". Archived from the original on 2018-12-01. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ Linares, Abel (1899). Cuba, An Illustrated Guide Book on the Island: Its History and Resources. Havana: Wilson's Book Store. p. 107.

- ^ "Our Gunboats Fired On" (PDF). New York Times. 8 May 1898.

- ^ Plaque on the site of the gun.

- ^ "Princesa Cathaysa " LA NIÑA GUANCHE "". 9 March 2014. Archived from the original on 2019-01-15. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ "NATIONAL Hotel, Havana and its 'Cueva de Taganana'". January 29, 2017. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Construcción para la Ciudad de La Habana

- Calle Belascoain

- BELASCOAIN - (vídeo musical)

- CALLE SAN LAZARO CENTRO HABANA

- Ruinas de la calle San Lázaro, Ctro.Habana. Ruins of San Lázaro Street.

- SAN LÁZARO 🇨🇺 LA CALLE MÁS DESTRUIDA DE LA HABANA

- La Casa de Beneficencia de la Habana.

- JAI ALAI - HABANA ‘El Palacio de los Gritos’

- Cuban Grand Prix - 1958