Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte | |

|---|---|

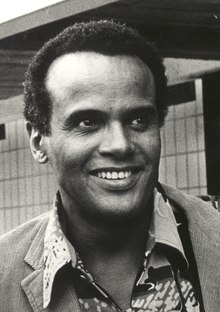

Belafonte in 1970 | |

| Born | Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. March 1, 1927 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | April 25, 2023 (aged 96) New York City, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1948–2023 |

| Works | Discography |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Marguerite Byrd

(m. 1948; div. 1957)Pamela Frank (m. 2008) |

| Children | 4, including Shari and Gina |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instrument | Vocals |

Harry Belafonte (/ˌbɛləˈfɒnti/ BEL-ə-FON-tee; born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.; March 1, 1927 – April 25, 2023) was an American singer, actor, and civil rights activist who popularized calypso music with international audiences in the 1950s and 1960s. Belafonte's career breakthrough album Calypso (1956) was the first million-selling LP by a single artist.[1]

Belafonte was best known for his recordings of "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)", "Jump in the Line (Shake, Senora)", "Jamaica Farewell", and "Mary's Boy Child". He recorded and performed in many genres, including blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. He also starred in films such as Carmen Jones (1954), Island in the Sun (1957), Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), Buck and the Preacher (1972), and Uptown Saturday Night (1974). He made his final feature film appearance in Spike Lee's BlacKkKlansman (2018).

Belafonte considered the actor, singer, and activist Paul Robeson to be a mentor. Belafonte was also a close confidant of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s and acted as the American Civil Liberties Union celebrity ambassador for juvenile justice issues.[2] He was also a vocal critic of the policies of the George W. Bush and Donald Trump administrations.

Belafonte won three Grammy Awards, including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, an Emmy Award,[3] and a Tony Award. In 1989, he received the Kennedy Center Honors. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. In 2014, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the academy's 6th Annual Governors Awards[4] and in 2022 was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the Early Influence category.[5] He is one of the few performers to have received an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony (EGOT), although he won the Oscar in a non-competitive category.

Early life

[edit]Belafonte was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.[6] on March 1, 1927, at Lying-in Hospital in Harlem, New York, the son of Jamaican-born parents Harold George Bellanfanti Sr. (1900–1990), who worked as a chef, and Melvine Love (1906–1988), a housekeeper.[7][8][9] There are disputed claims of his father's place of birth, which is also stated as Martinique.[10]

His mother was the child of a Scottish Jamaican mother and an Afro-Jamaican father, and his father was the child of an Afro-Jamaican mother and a Dutch-Jewish father of Sephardic Jewish descent. Harry Jr. was raised Catholic and attended parochial school at St. Charles Borromeo.[11]

From 1932 to 1940, Belafonte lived with one of his grandmothers in her native country of Jamaica, where he attended Wolmer's Schools. Upon returning to New York City, he dropped out of George Washington High School,[12] after which he joined the U.S. Navy and served during World War II.[13][14] In the 1940s, he worked as a janitor's assistant, during which a tenant gave him, as a gratuity, two tickets to see the American Negro Theater. He fell in love with the art form and befriended Sidney Poitier, who was also financially struggling. They regularly purchased a single seat to local plays, trading places in between acts, after informing the other about the progression of the play.[15]

At the end of the 1940s, Belafonte took classes in acting at the Dramatic Workshop of The New School in New York City with the influential German director Erwin Piscator alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur, and Poitier, while performing with the American Negro Theater.[16] He subsequently received a Tony Award for his participation in the Broadway revue John Murray Anderson's Almanac (1954).[17] He also starred in the 1955 Broadway revue 3 for Tonight with Gower Champion.[18]

Musical career

[edit]

Early years (1949–1955)

[edit]Belafonte started his career in music as a club singer in New York to pay for his acting classes.[19] The first time he appeared in front of an audience, he was backed by the Charlie Parker band, which included Charlie Parker, Max Roach, and Miles Davis, among others.[20] He launched his recording career as a pop singer on the Roost label in 1949, but quickly developed a keen interest in folk music, learning material through the Library of Congress' American folk songs archives. Along with guitarist and friend Millard Thomas, Belafonte soon made his debut at the legendary jazz club The Village Vanguard.[21] He signed a contract with RCA Victor in 1953, recording regularly for the label until 1974.[22] Belafonte also performed during the Rat Pack era in Las Vegas.[23] Belafonte's first widely released single, which went on to become his "signature" audience participation song in virtually all his live performances, was "Matilda", recorded April 27, 1953.[22] Between 1953 and 1954, he was a cast member of the Broadway musical revue and sketch comedy show John Murray Anderson's Almanac where he sang Mark Twain,[24] of which he was also the songwriter.[citation needed]

Rise to fame (1956–1958)

[edit]

Following his success in the film Carmen Jones (1954), Belafonte had his breakthrough album with Calypso (1956), which became the first LP in the world to sell more than one million copies in a year.[25] He stated that it was the first million-selling album ever in England. The album is number four on Billboard's "Top 100 Album" list for having spent 31 weeks at number 1, 58 weeks in the top ten, and 99 weeks on the U.S. chart.[26] The album introduced American audiences to calypso music, which had originated in Trinidad and Tobago in the early 19th century, and Belafonte was dubbed the "King of Calypso", a title he wore with reservations since he had no claims to any Calypso Monarch titles.[27]

One of the songs included in the album is the now famous "Banana Boat Song", listed as "Day-O" on the Calypso LP, which reached number five on the pop chart and featured its signature lyric "Day-O".[28]

Many of the compositions recorded for Calypso, including "Banana Boat Song" and "Jamaica Farewell", gave songwriting credit to Irving Burgie.[29]

In the United Kingdom, "Banana Boat Song" was released in March 1957 and spent ten weeks in the top 10 of the UK singles chart, reaching a peak of number two, and in August, "Island in the Sun" reached number three, spending 14 weeks in the top 10. In November, "Mary's Boy Child" reached number one in the UK, where it spent seven weeks.[30]

Middle career (1959–1970)

[edit]

While primarily known for calypso, Belafonte recorded in many different genres, including blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. His second-most popular hit, which came immediately after "The Banana Boat Song", was the comedic tune "Mama Look at Bubu", also known as "Mama Look a Boo-Boo", originally recorded by Lord Melody in 1955,[31] in which he sings humorously about misbehaving and disrespectful children. It reached number 11 on the pop chart.[32]

In 1959, Belafonte starred in Tonight With Belafonte, a nationally televised special that featured Odetta, who sang "Water Boy" and performed a duet with Belafonte of "There's a Hole in My Bucket" that hit the national charts in 1961.[33] Belafonte was the first Jamaican American to win an Emmy, for Revlon Revue: Tonight with Belafonte (1959).[3] Two live albums, both recorded at Carnegie Hall in 1959 and 1960, enjoyed critical and commercial success. From his 1959 album, "Hava Nagila" became part of his regular routine and one of his signature songs.[34] He was one of many entertainers recruited by Frank Sinatra to perform at the inaugural gala of President John F. Kennedy in 1961, which included Ella Fitzgerald and Mahalia Jackson, among others.[35] Later that year, RCA Victor released another calypso album, Jump Up Calypso, which went on to become another million seller. During the 1960s he introduced several artists to U.S. audiences, most notably South African singer Miriam Makeba and Greek singer Nana Mouskouri. His album Midnight Special (1962) included Bob Dylan as harmonica player.[36]

As the Beatles and other stars from Britain began to dominate the U.S. pop charts, Belafonte's commercial success diminished; 1964's Belafonte at The Greek Theatre was his last album to appear in Billboard's Top 40. His last hit single, "A Strange Song", was released in 1967 and peaked at number 5 on the adult contemporary music charts. Belafonte received Grammy Awards for the albums Swing Dat Hammer (1960) and An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba (1965), the latter of which dealt with the political plight of black South Africans under apartheid. He earned six Gold Records.[37]

During the 1960s, Belafonte appeared on TV specials alongside artists such as Julie Andrews, Petula Clark, Lena Horne, and Nana Mouskouri. In 1967, Belafonte was the first non-classical artist to perform at the prestigious Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC) in Upstate New York,[38] soon to be followed by concerts there by the Doors, the 5th Dimension, the Who, and Janis Joplin.

From February 5 to 9, 1968, Belafonte guest hosted The Tonight Show substituting for Johnny Carson.[39] Among his interview guests were Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy.[39][40]

Later recordings and subsequent activities (1971–2017)

[edit]Belafonte's fifth and final calypso album, Calypso Carnival, was issued by RCA in 1971.[41] Belafonte's recording activity slowed down after releasing his final album for RCA in 1974. From the mid-1970s to early 1980s, Belafonte spent most of his time on tour, which included concerts in Japan, Europe, and Cuba.[42] In 1977, Columbia Records released the album Turn the World Around, with a strong focus on world music.[43]

In 1978, he appeared as a guest star on an episode of The Muppet Show, on which he performed his signature song "Day-O".[44] However, the episode is best known for Belafonte's rendition of the spiritual song "Turn the World Around", from the album of the same name, which he performed with specially made Muppets that resembled African tribal masks.[45][46] It became one of the series' most famous performances and was reportedly Jim Henson's favorite episode. After Henson's death in May 1990, Belafonte was asked to perform the song at Henson's memorial service.[46][47] "Turn the World Around" was also included in the 2005 official hymnal supplement of the Unitarian Universalist Association, Singing the Journey.[48]

From 1979 to 1989, Belafonte served on the Royal Winnipeg Ballet's board of directors.[49]

In December 1984, soon after Band Aid, a group of popular British and Irish artists, released Do They Know It's Christmas? Belafonte decided to create an American benefit single for African famine relief. With fundraiser Ken Kragen, he enlisted Lionel Richie, Kenny Rogers, Stevie Wonder, Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson, The song they produced and recorded, "We Are the World", brought together some of the era's best-known American musicians and is the eighth-best-selling single of all time with physical sales in excess of 20 million copies. In 1986 the American Music Awards named "We Are the World" "Song of the Year", and honored Belafonte with the Award of Appreciation.

Belafonte released his first album of original material in over a decade, Paradise in Gazankulu, in 1988, which contained ten protest songs against the South African former Apartheid policy, and was his last studio album.[50] In the same year Belafonte, as UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, attended a symposium in Harare, Zimbabwe, to focus attention on child survival and development in Southern African countries. As part of the symposium, he performed a concert for UNICEF. A Kodak video crew filmed the concert, which was released as a 60-minute concert video titled Global Carnival.[51]

Following a lengthy recording hiatus, An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends, a soundtrack and video of a televised concert, were released in 1997 by Island Records.[52] The Long Road to Freedom: An Anthology of Black Music, a huge multi-artist project recorded by RCA during the 1960s and 1970s, was finally released by the label in 2001. Belafonte went on the Today Show to promote the album on September 11, 2001, and was interviewed by Katie Couric just minutes before the first plane hit the World Trade Center.[53] The album was nominated for the 2002 Grammy Awards for Best Boxed Recording Package, for Best Album Notes, and for Best Historical Album.[54]

Belafonte received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1989.[55] He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994 and he won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000. He performed sold-out concerts globally through the 1950s to the 2000s. His last concert was a benefit concert for the Atlanta Opera on October 25, 2003. In a 2007 interview, he stated that he had since retired from performing.[56]

On January 29, 2013, Belafonte was the keynote speaker and 2013 honoree for the MLK Celebration Series at the Rhode Island School of Design. Belafonte used his career and experiences with Dr. King to speak on the role of artists as activists.[57]

Belafonte was inducted as an honorary member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity on January 11, 2014.[58]

In March 2014, Belafonte was awarded an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of Music in Boston.[59]

In 2017, Belafonte released When Colors Come Together, an anthology of some of his earlier recordings, produced by his son David, who wrote lyrics for an updated version of "Island In The Sun", arranged by longtime Belafonte musical director Richard Cummings, and featuring Harry Belafonte's grandchildren Sarafina and Amadeus and a children's choir.[60]

Film career

[edit]Early film career (1953–1956)

[edit]

Belafonte starred in numerous films. His first film role was in Bright Road (1953), in which he supported female lead Dorothy Dandridge.[61] The two subsequently starred in Otto Preminger's hit musical Carmen Jones (1954). Ironically, Belafonte's singing in the film was dubbed by an opera singer, as was Dandridge's, both voices being deemed unsuitable for their roles.[16][61]

Rise as an actor (1957–1959)

[edit]Realizing his own star power, Belafonte was subsequently able to land several (then) controversial film roles. In Island in the Sun (1957), there are hints of an affair between Belafonte's character and the character played by Joan Fontaine;[62] the film also starred James Mason, Dandridge, Joan Collins, Michael Rennie, and John Justin. In 1959, Belafonte starred in and produced (through his company HarBel Productions) Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow, in which Belafonte plays a bank robber uncomfortably teamed with a racist partner (Robert Ryan). Belafonte also co-starred with Inger Stevens in The World, the Flesh and the Devil.[63] Belafonte was offered the role of Porgy in Preminger's Porgy and Bess, where he would have once again starred opposite Dandridge, but refused the role because he objected to its racial stereotyping; Sidney Poitier played the role instead.[64][65]

Later film and theatre involvement (1960–2018)

[edit]

Dissatisfied with most of the film roles offered to him during the 1960s, Belafonte concentrated on music. In the early 1970s, Belafonte appeared in more films, among which are two with Poitier: Buck and the Preacher (1972) and Uptown Saturday Night (1974).[66] In 1984, Belafonte produced and scored the musical film Beat Street, dealing with the rise of hip-hop culture.[67] Together with Arthur Baker, he produced the gold-certified soundtrack of the same name.[68] Four of his songs appeared in the 1988 film Beetlejuice, including "Day-O" and "Jump in the Line (Shake, Senora)".

Belafonte next starred in a major film in the mid-1990s, appearing with John Travolta in the race-reverse drama White Man's Burden (1995);[69] and in Robert Altman's jazz age drama Kansas City (1996), the latter of which garnered him the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Supporting Actor.[70] He also starred as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States in the TV drama Swing Vote (1999).[69] In 2006, Belafonte appeared in Bobby, Emilio Estevez's ensemble drama about the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy; he played Nelson, a friend of an employee of the Ambassador Hotel (Anthony Hopkins).[66]

His final film appearance was in Spike Lee's Academy Award-winning BlacKkKlansman (2018) as an elderly civil rights pioneer.[10]

Political activism

[edit]

Belafonte is said to have married politics and pop culture.[71] Belafonte's political beliefs were greatly inspired by the singer, actor, and civil rights activist Paul Robeson, who mentored him.[72] Robeson opposed not only racial prejudice in the United States but also western colonialism in Africa. Belafonte refused to perform in the American South from 1954 until 1961.[73]

Belafonte gave the keynote address at the ACLU of Northern California's annual Bill of Rights Day Celebration In December 2007 and was awarded the Chief Justice Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award. The 2011 Sundance Film Festival featured the documentary film Sing Your Song, a biographical film focusing on Belafonte's contribution to and his leadership in the civil rights movement in America and his endeavors to promote social justice globally.[74] In 2011, Belafonte's memoir My Song was published by Knopf Books.[75]

Involvement in the civil rights movement

[edit]

Belafonte supported the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s and was one of Martin Luther King Jr.'s confidants.[76] After King had been arrested for his involvement in the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, he began traveling to Northern cities to spread awareness and acquire donations for those struggling with social segregation and oppression in the South.[77] The two met at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York, in March of the following year. This interaction led to years of joint political activism and friendship. Belafonte joined King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, during the 1958 Washington D.C. Youth March for Integrated Schools, and in 1963, he backed King in conversations with Robert F. Kennedy, helping to organize the 1963 March on Washington[78]—the site of King's famous "I Have a Dream" Speech.[79] He provided for King's family since King earned only $8,000 ($80,000 in today's money) a year as a preacher. As with many other civil rights activists, Belafonte was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. During the 1963 Birmingham campaign, Belafonte bailed King out of the Birmingham, Alabama jail and raised $50,000[80] to release other civil rights protesters. He contributed to the 1961 Freedom Rides, and supported voter registration drives[78][81] He later recalled, "Paul Robeson had been my first great formative influence; you might say he gave me my backbone. Martin King was the second; he nourished my soul."[82] Throughout his career, Belafonte was an advocate for political and humanitarian causes, such as the Anti-Apartheid Movement and USA for Africa. From 1987 until his death, he was a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador.[83]

During the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, Belafonte bankrolled the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, flying to Mississippi that August with Sidney Poitier and $60,000 in cash and entertaining crowds in Greenwood. In 1968, Belafonte appeared on a Petula Clark primetime television special on NBC. In the middle of a duet of On the Path of Glory, Clark smiled and briefly touched Belafonte's arm,[84] which prompted complaints from Doyle Lott, the advertising manager of the show's sponsor, Plymouth Motors.[85] Lott wanted to retape the segment,[86] but Clark, who had ownership of the special, told NBC that the performance would be shown intact or she would not allow it to be aired at all. Newspapers reported the controversy,[87][88] Lott was relieved of his responsibilities,[89] and when the special aired, it attracted high ratings.

Belafonte taped an appearance on an episode of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour to be aired on September 29, 1968, performing a controversial Mardi Gras number intercut with footage from the 1968 Democratic National Convention riots. CBS censors deleted the segment. The full unedited content was broadcast in 1993 as part of a complete Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour syndication package.[citation needed]

Involvement in the Kennedy campaign

[edit]In the 1960 election between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, notable Black athlete Jackie Robinson advocated his support for the Nixon campaign. His reasoning for doing so was his perception of Kennedy's championing of the Civil Rights movement as disingenuous.[90] Because of Robinson's social impact on Black Americans, the Democratic Party was determined to find a comparable Black endorser for Kennedy's campaign.[91] Fresh off of his win as the first Black man to receive an Emmy Award for his work on Tonight with Belafonte, Belafonte was Kennedy's pick to fill the endorsement position.[79]

The two met in Belafonte's apartment, where Kennedy had hoped to convince Belafonte to mobilize support for his campaign. He thought to accomplish this by having Belafonte mobilize his influence amongst other Black entertainers of the era, persuading them to rally for Kennedy's presidential nomination. Unexpectedly, Belafonte was not so impressed by the candidate, sharing the same sentiments as Robinson about Kennedy's role (or lack thereof) in maintaining civil rights as an essential part of his campaign. To improve his engagement with Black America, Belafonte suggested to Kennedy that he contact Martin Luther King, making a connection to a viable source of leadership within the movement. Kennedy, though, was hesitant with this suggestion, questioning the social impact the preacher could make on the campaign. After much convincing–as Kennedy and King would later meet in June 1960–the two men negotiated a deal that if Nixon became the nominee for the Republican party, Belafonte would support Kennedy's presidential pursuits.[79] Belafonte's endorsement of the campaign was further substantiated after both Kennedy brothers had worked to bail King out of jail in Atlanta after a sit-in, engaging with a Georgia judge.[91]

Joining the Hollywood for Kennedy committee,[79] Belafonte appeared in a 1960 campaign commercial for Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy.[92] Unfortunately, the commercial was shown on television for one broadcasting.[77] Belafonte also attended and performed at Kennedy's inaugural ball.[91] Kennedy later named Belafonte cultural advisor to the Peace Corps. After Kennedy's assassination, Belafonte supported Lyndon B. Johnson for the 1964 United States presidential election.[93]

The Baldwin-Kennedy Meeting

[edit]Renowned author James Baldwin contacted Belafonte three years after John F. Kennedy's election. The purpose of the call was to invite Belafonte to a meeting to speak with Attorney General Robert Kennedy about the continued plight of the Black people in America. This event was known as the Baldwin-Kennedy Meeting. Belafonte met with fifteen others, including Kennedy and Baldwin, in Kennedy's Central Park South apartment on May 24, 1963.[91]

The other members included were Thais Aubrey, David Baldwin, Edwin Berry, Kenneth Clark, Eddie Fales, Lorraine Hansberry, Lena Horne, Clarence Jones, Burke Marshall, Henry Morgenthau III, June Shagaloff, Jerome Smith, and Rip Torn.[94]

The guests engaged in cordial political and social conversation. Later, the talk led to an investigation of the position of Black people in the Vietnam War. Offended by Kennedy's implication that Black men should serve in the war, Jerome Smith scolded the young Attorney General. Smith, a Black man and Civil Rights advocate had been severely beaten while fighting for the movement's cause, which enforced his strong resistance to Kennedy's assertion, frustrated that he should fight for a country that did not seem to want to fight for him.[91]

A short time after the confrontation, Belafonte spoke with Kennedy. Belafonte then told him that even with the meeting's tension, he needed to be in the presence of a man like Smith to understand Black people's frustration with patriotism that Kennedy and other leaders could not understand.[91]

Obama administration

[edit]In the 1950s, Belafonte was a supporter of the African American Students Foundation, which gave a grant to Barack Obama Sr., the late father of 44th U.S. president Barack Obama, to study at the University of Hawaii in 1959.[95]

In 2011, Belafonte commented on the Obama administration and the role that popular opinion played in shaping its policies. "I think [Obama] plays the game that he plays because he sees no threat from evidencing concerns for the poor."[96]

On December 9, 2012, in an interview with Al Sharpton on MSNBC, Belafonte expressed dismay that many political leaders in the United States continue to oppose Obama's policies even after his reelection: "The only thing left for Barack Obama to do is to work like a third-world dictator and just put all of these guys in jail. You're violating the American desire."[97]

On February 1, 2013, Belafonte received the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, and in the televised ceremony, he counted Constance L. Rice among those previous recipients of the award whom he regarded highly for speaking up "to remedy the ills of the nation."[98]

In November 2014, Belafonte attended “Revolution and Religion,” a dialogue between Bob Avakian and Cornel West at Riverside Church in New York City.[99]

Support for Bernie Sanders

[edit]In 2016, Belafonte endorsed Vermont U.S. senator Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primaries, saying: "I think he represents opportunity, I think he represents a moral imperative, I think he represents a certain kind of truth that's not often evidenced in the course of politics."[100]

Belafonte was an honorary cochairman of the Women's March on Washington, which took place on January 21, 2017, the day after the inauguration of Donald Trump as president.[101]

The Sanders Institute

[edit]Belafonte was a fellow at The Sanders Institute.[102]

Humanitarian activism

[edit]

HIV/AIDS crisis

[edit]In 1985, Belafonte helped organize the Grammy Award-winning song "We Are the World", a multi-artist effort to raise funds for Africa. He performed in the Live Aid concert that same year. In 1987, he received an appointment to UNICEF as a goodwill ambassador. Following his appointment, Belafonte traveled to Dakar, Senegal, where he served as chairman of the International Symposium of Artists and Intellectuals for African Children. He also helped to raise funds—along with more than 20 other artists—in the largest concert ever held in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1994, he embarked on a mission to Rwanda and launched a media campaign to raise awareness of the needs of Rwandan children.[21]

In 2001, Belafonte visited South Africa to support the campaign against HIV/AIDS.[103] In 2002, Africare awarded him the Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Service Award for his efforts.[45] In 2004, Belafonte traveled to Kenya to stress the importance of educating children in the region.[104]

Prostate Cancer awareness

[edit]Belafonte had been involved in prostate cancer advocacy since 1996, when he was diagnosed and successfully treated for the disease.[105] On June 27, 2006, Belafonte received the BET Humanitarian Award at the 2006 BET Awards. He was named one of nine 2006 Impact Award recipients by AARP: The Magazine.[106]

Work with UNICEF

[edit]On October 19, 2007, Belafonte represented UNICEF on Norwegian television to support the annual telethon (TV Aksjonen) and helped raise a world record of $10 per Norwegian citizen.[107]

Various Activist work

[edit]Belafonte was also an ambassador for the Bahamas.[108] He sat on the board of directors of the Advancement Project.[109] He also served on the advisory council of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.[110]

New York City Pride Parade

[edit]In 2013, Belafonte was named a grand marshal of the New York City Pride Parade alongside Edie Windsor and Earl Fowlkes.[111]

Belafonte and foreign policy

[edit]Belafonte was a longtime critic of U.S. foreign policy. He began making controversial political statements on the subject in the early 1980s. At various times, he made statements opposing the U.S. embargo on Cuba; praising Soviet peace initiatives; attacking the U.S. invasion of Grenada; praising the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; honoring Ethel and Julius Rosenberg; and praising Fidel Castro.[61][112] Belafonte is also known for his visit to Cuba that helped ensure hip-hop's place in Cuban society. According to Geoffrey Baker's article "Hip hop, Revolucion! Nationalizing Rap in Cuba", in 1999, Belafonte met with representatives of the rap community immediately before meeting with Castro. This meeting resulted in Castro's personal approval of, and hence the government's involvement in, the incorporation of rap into his country's culture.[113] In a 2003 interview, Belafonte reflected upon this meeting's influence:

"When I went back to Havana a couple years later, the people in the hip-hop community came to see me and we hung out for a bit. They thanked me profusely and I said, 'Why?' and they said, 'Because your little conversation with Fidel and the Minister of Culture on hip-hop led to there being a special division within the ministry and we've got our own studio.'."[114]

Belafonte was active in the Anti-Apartheid Movement. In 1987, he was the master of ceremonies at a reception honoring African National Congress President Oliver Tambo at Roosevelt House, Hunter College, in New York City. The reception was held by the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) and The Africa Fund.[115] He was a board member of the TransAfrica Forum and the Institute for Policy Studies.[116]

Opposition to the George W. Bush administration

[edit]Belafonte achieved widespread attention for his political views in 2002 when he began making a series of comments about President George W. Bush, his administration and the Iraq War. During an interview with Ted Leitner for San Diego's 760 KFMB, on October 10, 2002, Belafonte referred to Malcolm X.[117] Belafonte said:

There is an old saying, in the days of slavery. There were those slaves who lived on the plantation, and there were those slaves who lived in the house. You got the privilege of living in the house if you served the master, do exactly the way the master intended to have you serve him. That gave you privilege. Colin Powell is permitted to come into the house of the master, as long as he would serve the master, according to the master's dictates. And when Colin Powell dares to suggest something other than what the master wants to hear, he will be turned back out to pasture. And you don't hear much from those who live in the pasture.[118]

Belafonte used the quotation to characterize former United States Secretaries of State Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice. Powell and Rice both responded, with Powell calling the remarks "unfortunate"[117] and Rice saying: "I don't need Harry Belafonte to tell me what it means to be black."[119]

The comment resurfaced in an interview with Amy Goodman for Democracy Now! in 2006.[120] In January 2006, Belafonte led a delegation of activists including actor Danny Glover and activist/professor Cornel West to meet with Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. In 2005, Chávez, an outspoken Bush critic, initiated a program to provide cheaper heating oil for poor people in several areas of the United States. Belafonte supported this initiative.[121] He was quoted as saying, during the meeting with Chávez: "No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we're here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people support your revolution."[122] Belafonte and Glover met again with Chávez in 2006.[123] The comment ignited a great deal of controversy. Hillary Clinton refused to acknowledge Belafonte's presence at an awards ceremony that featured both of them.[124] AARP, which had just named him one of its 10 Impact Award honorees 2006, released this statement following the remarks: "AARP does not condone the manner and tone which he has chosen and finds his comments completely unacceptable."[125]

During a Martin Luther King Jr. Day speech at Duke University in 2006, Belafonte compared the American government to the hijackers of the September 11 attacks, saying: "What is the difference between that terrorist and other terrorists?"[126] In response to criticism about his remarks, Belafonte asked: "What do you call Bush when the war he put us in to date has killed almost as many Americans as died on 9/11 and the number of Americans wounded in war is almost triple? ... By most definitions Bush can be considered a terrorist." When he was asked about his expectation of criticism for his remarks on the war in Iraq, Belafonte responded: "Bring it on. Dissent is central to any democracy."[127]

In another interview, Belafonte remarked that while his comments may have been "hasty", he felt that the Bush administration suffered from "arrogance wedded to ignorance" and its policies around the world were "morally bankrupt."[128] In a January 2006 speech to the annual meeting of the Arts Presenters Members Conference, Belafonte referred to "the new Gestapo of Homeland Security", saying: "You can be arrested and have no right to counsel!"[129] During a Martin Luther King Jr. Day speech at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina in January 2006, Belafonte said that if he could choose his epitaph, it would read "Harry Belafonte, Patriot."[130]

In 2004, he was awarded the Domestic Human Rights Award in San Francisco by Global Exchange.[citation needed]

Business career

[edit]Belafonte liked and often visited the Caribbean island of Bonaire.[131] He and Maurice Neme of Oranjestad, Aruba, formed a joint venture to create a luxurious private community on Bonaire named Belnem, a portmanteau of the two men's names. Construction began on June 3, 1966.[132] The neighborhood is managed by the Bel-Nem Caribbean Development Corporation. Belafonte and Neme served as its first directors.[133] In 2017, Belnem was home to 717 people.[134]

Personal life, health and death

[edit]

Belafonte and Marguerite Byrd were married from 1948 to 1957. They had two daughters: Adrienne and Shari. They separated when Byrd was pregnant with Shari.[71] Adrienne and her daughter Rachel Blue founded the Anir Foundation/Experience, focused on humanitarian work in southern Africa.[135]

In 1953, Belafonte was financially able to move from Washington Heights, Manhattan, "into a white neighborhood in East Elmhurst, Queens."[136]

Belafonte had an affair with actress Joan Collins during the filming of Island in the Sun.[137]

On March 8, 1957, Belafonte married his second wife Julie Robinson (1928–2024), a dancer with the Katherine Dunham Company who was of Jewish descent.[138] They had two children: Gina and David.[139] After 47 years of marriage,[140] Belafonte and Robinson divorced in 2004.

In Fall 1958, Belafonte was looking for an apartment to rent on the Upper West Side. After he had been turned away from other apartment buildings due to being black, he had his white publicist rent an apartment at 300 West End Avenue for him. When he moved in, and the owner realized that he was an African American, he was asked to leave. Belafonte not only refused, but he also used three dummy real estate companies to buy the building and converted it into a co-op, inviting his friends, both white and black, to buy apartments. He lived in the 21-room, 6-bedroom apartment for 48 years.[141] In April 2008, he married Pamela Frank, a photographer.[142]

Belafonte had five grandchildren: Rachel and Brian through his children with Marguerite Byrd, and Maria, Sarafina and Amadeus through his children with Robinson. He had two great-grandchildren by his oldest grandson Brian. In October 1998, Belafonte contributed a letter to Liv Ullmann's book Letter to My Grandchild.[143]

In 1996, Belafonte was diagnosed with prostate cancer and was treated for the disease. He suffered a stroke in 2004, which took away his inner-ear balance. From 2019, Belafonte's health began to decline, but he remained an active and prominent figure in the civil rights movement.[citation needed]

Belafonte died from congestive heart failure at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York City, on April 25, 2023, at the age of 96.[10]

Discography

[edit]Belafonte released 27 studio albums, 8 live albums, and 6 collaborations, and achieved critical and commercial success.

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Bright Road | Mr. Williams | [144] | |

| 1954 | Carmen Jones | Joe | [144] | |

| 1957 | Island in the Sun | David Boyeur | [144] | |

| The Heart of Show Business | Short | [145] | ||

| 1959 | The World, the Flesh and the Devil | Ralph Burton | [144] | |

| Odds Against Tomorrow | Johnny Ingram | [144] | ||

| 1970 | The Angel Levine | Alexander Levine | [144] | |

| 1972 | Buck and the Preacher | Preacher | [144] | |

| 1974 | Uptown Saturday Night | Dan "Geechie Dan" Beauford | [144] | |

| 1983 | Drei Lieder | Short | [146] | |

| 1992 | The Player | Cameo | [147] | |

| 1994 | Ready to Wear | Cameo | [148] | |

| 1995 | White Man's Burden | Thaddeus Thomas | [144] | |

| 1996 | Kansas City | Seldom Seen | [144] | |

| 2006 | Bobby | Nelson | [144] | |

| 2018 | BlacKkKlansman | Jerome Turner | [144] |

- Documentary

| Year | Title | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | King: A Filmed Record... Montgomery to Memphis | [149] |

| 1981 | Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker | [150] |

| 1982 | A veces miro mi vida | [147] |

| 1983 | Sag nein | [147] |

| 1984 | Der Schönste Traum | [151] |

| 1989 | We Shall Overcome | [147] |

| 1995 | Hank Aaron: Chasing the Dream | [152] |

| 1996 | Jazz '34 | [144] |

| 1998 | Scandalize My Name: Stories from the Blacklist | [147] |

| 2001 | Fidel | [147] |

| 2003 | XXI Century | [152] |

| Conakry Kas | [153] | |

| 2004 | Ladders | [154] |

| 2010 | Motherland | [155] |

| 2011 | Sing Your Song | [144] |

| 2013 | Hava Nagila: The Movie | [144] |

| 2020 | The Sit-In: Harry Belafonte hosts the Tonight Show | [144] |

Television

[edit]

- Sugar Hill Times (1949–1950)[156]

- The Ed Sullivan Show (1953–1964)[157]

- The Nat King Cole Show (1957)[158]

- The Steve Allen Show (1958)[159]

- Tonight With Belafonte (1959)[160]

- Round Table on March on Washington (1963)[161]

- The Danny Kaye Show (1965)[162]

- Petula (1968)[163]

- The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1968)[164]

- The Tonight Show (1968)[165]

- A World in Music (1969)[166]

- Harry & Lena, For The Love Of Life (1969)[167]

- A World in Love (1970)[166]

- The Flip Wilson Show (1973)[168]

- Free to Be ... You and Me (1974)[169]

- The Muppet Show (1978)[170]

- Grambling's White Tiger (1981)[144]

- Don't Stop The Carnival (1985)[171]

- After Dark (1988) (extended appearance on political discussion programme, more here)[172]

- An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends (1997)[52]

- Swing Vote (1999)[173]

- Swing Vote (1999 TV movie)[144]

- PB&J Otter "The Ice Moose" (1999)[174]

- Tanner on Tanner (2004)[175]

- That's What I'm Talking About (2006) (miniseries)[176]

- When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) (miniseries)[177]

- Speakeasy, interviewing Carlos Santana (2015)[178]

Concert videos

[edit]- En Gränslös Kväll På Operan (1966)[179]

- Don't Stop The Carnival (1985)[180]

- Global Carnival (1988)[51]

- An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends (1997)[52]

Theatre

[edit]- John Murray Anderson's Almanac (1953)[181]

- 3 for Tonight (1955)[182][183]

- Moonbirds (1959) (producer)[184]

- Belafonte at the Palace (1959)[185]

- Asinamali! (1987) (producer)[184]

Accolades and legacy

[edit]Belafonte is an EGOT honoree, having received three Grammy Awards, an Emmy Award,[3] a Tony Award,[186] and, in 2014, the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences' 6th Annual Governors Awards.[187]

Belafonte won an Emmy in 1960 for his performance on Revlon Revue. He was nominated four other times.[188]

| Award | Theatrical Production | Role | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tony Award[186] | John Murray Anderson's Almanac | Best Performance by a Featured Actor in a Musical | 1954 |

| Theatre World Awards[189] | John Murray Anderson's Almanac | Award Winner | 1954 |

| Donaldson Award[190] | John Murray Anderson's Almanac | Best Actor Debut in a Musical | 1954 |

He also received various honours including the Kennedy Center Honors in 1989, the National Medal of Arts in 1994 and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the Early Influence category in 2022.[5]

Belafonte celebrated his 93rd birthday on March 1, 2020, at Harlem's Apollo Theater in a tribute event that concluded "with a thunderous audience singalong" with rapper Doug E. Fresh to 1956's "Banana Boat Song". Soon after, the New York Public Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture announced it had acquired Belafonte's vast personal archive of "photographs, recordings, films, letters, artwork, clipping albums," and other content.[191]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Harry Belafonte – Calypso". AllMusic. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "ACLU Ambassadors – Harry Belafonte". American Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Awards search for Harry Belafonte". Emmys. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Sinha-Roy, Piya (August 28, 2014). "Belafonte, Miyazaki to receive Academy's Governors Awards". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ a b "Artist: Harry Belafonte: Early Influence Award". WKYC. 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ "Life in Harlem". Sing Your Song. S2BN Belafonte Productions. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Fogelson, Genia (1996). Harry Belafonte. Holloway House Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 0-87067-772-1.

- ^ Hardy, Phil; Laing, Dave (1990). The Faber Companion to Twentieth Century Music. Faber. p. 54. ISBN 0-571-16848-5.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Biography (1927–)". Film Reference. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c Keepnews, Peter (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, 96, Dies; Barrier-Breaking Singer, Actor and Activist". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Keillor, Garrison (October 21, 2011). "The Radical Entertainment of Harry Belafonte (Published 2011)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Arenson, Karen W. (June 2, 2000), "Commencements; Belafonte Lauds Diversity Of Baruch College Class", The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2008. "(He said that he had not gotten past the first year at George Washington High School, and that the only college degrees he had were honorary ones.)"

- ^ The African American Registry Harry Belafonte, an entertainer of truth Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, singer, actor and activist, has died at age 96". WUNC. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ Belafonte, Harry (October 12, 2011). "Harry Belafonte: Out Of Struggle, A Beautiful Voice". NPR. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Susman, Gary (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte – Singer, Actor, and Activist – Has Died at 96". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, singer, actor and tireless activist, dies aged 96". The Guardian. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Hall, Margaret (April 25, 2023). "Tony Winner Harry Belafonte Passes Away at 96". Playbill. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Chad (October 25, 2019). "Harry Belafonte". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Myers, Marc (February 15, 2017). "Jazz news: Harry Belafonte: 1949". All About Jazz. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "Iconic Voices of Black History – Harry Belafonte". VocaliD. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Johnson, Alex; Dasrath, Diana (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, calypso star and civil rights champion, dies at 96". NBC News. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Singer-activist Harry Belafonte dies at 96 due to heart failure". Free Press Journal. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "John Murray Anderson's Almanac (Broadway, Imperial Theatre, 1953)". Playbill.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte, singer, actor, activist, dies at 96". WCPO 9 Cincinnati. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Judith E. (2017). "'Calypso' – Harry Belafonte (1956)" (PDF). Library of Congress.

- ^ Puente, Maria (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, trailblazing singer, actor and activist, dies at 96". USA Today. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 18 – Blowin' in the Wind: Pop discovers folk music. [Part 1] : UNT Digital Library". Pop Chronicles. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, Mark (December 1, 2019). "Irving Burgie, songwriter of calypso hit 'Day-O,' dies at 95". USA Today. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte". Officialcharts.com. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ "Boo Boo Man (Mama Look a Boo Boo) by Caribbean Allstars, Lord Melody – Track Info | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2019). Joel Whitburn's top pop singles, 1955–2018. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-89820-233-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Odetta". WordPress. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Grossman, Roberta (2011). "Video – What does Hava Nagila mean?". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021.

- ^ "President-elect and Mrs. Kennedy arrive at the Inaugural Gala, January 19, 1961". JFK Library. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte, civil rights activist and trailblazing artist, dead at 96". Yahoo News. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Levith, Will (July 12, 2018). "5 Most Memorable Music Moments In SPAC History". Saratoga Living. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Bianculli, David (September 8, 2020). "'The Sit-In' Revisits A Landmark Week With Harry Belafonte As 'Tonight Show' Host". NPR. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "MLK Appears on "Tonight" Show with Harry Belafonte". The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. February 2, 1968. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte – Calypso Carnival Album Reviews, Songs & More | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte – Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) (Live)". Scranton Times-Tribune. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte – Turn the World Around Album Reviews, Songs & More | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Hennes, Joe (April 25, 2023). "RIP Muppet Show Guest Harry Belafonte". ToughPigs. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Chow, Andrew R. (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, Trailblazing Performer and Fierce Civil Rights Activist, Dies". Time. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Duquette, Michael (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte: The Icon's Life In Music, Movies and TV". Observer. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ McLevy, Alex (April 25, 2023). "R.I.P. Harry Belafonte, actor, singer, and Civil Rights icon". The A.V. Club. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Song Information". UUA. April 9, 2012. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Daylight come and we want to go to Winnipeg". Winnipeg Free Press. April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte – Paradise in Gazankulu Album Reviews, Songs & More | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "Harry Belafonte in Concert – Global Carnival (1988)". March 20, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c Heckman, Don (March 1, 1997). "Forever the Renaissance Man". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "NBC Sept. 11, 2001 8:31 am – 9:12 am". Internet Archive. September 11, 2001. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ Varga, George (April 25, 2023). "Appreciation: Harry Belafonte, dead at 96, championed 'Long Road to Freedom' in his music and his life". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Kennedy Center Announces '89 Awards". The New York Times. August 8, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "kostenloses PR und Pressemitteilungen". Pr-inside.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "2013 MLK Series Keynote Address – Harry Belafonte 'Artist as Activist'". RISD. January 29, 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen L. (January 12, 2014). "Harry Belafonte challenges Phi Beta Sigma to join movement to stop oppression of women". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "ACLU Ambassador Project". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Robertson, Iyana (February 15, 2017). "Harry Belafonte's 'When Colors Come Together' Proves the Truth About Children and Race". BET. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Morris, Chris (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, Calypso King Who Worked for African American Rights, Dies at 96". Variety. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte obituary: A US icon of music, film and civil rights". BBC News. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Variety Staff (January 1, 1959). "The World, the Flesh and the Devil". Variety. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Jnpickens (February 25, 2019). "Musical Monday: Porgy and Bess (1959)". Comet Over Hollywood. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte, the Activist Who Became an Artist, Dies at 96". autos.yahoo.com. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Obenson, Tambay (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, the Activist Who Became an Artist, Dies at 96". IndieWire. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Influenced Hip-Hop – From "Beat Street" To Social Justice In The Genre". AllHipHop. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "The Story of How 'Beat Street' Went From a Box Office Failure to One of Hip-Hop's Most Important Movies". Okayplayer.com. June 6, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Insider, Martin Holmes, TV (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte Dies: Singer, Actor & Activist Was 96". WFMZ.com. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bernstein, Adam (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, barrier-smashing entertainer and activist, dies at 96". Washington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "A Tribute to Black Icons – from Harry Belafonte to Whitney Houston – by the Family Members Who Know Them Best". People. February 21, 2022.

- ^ Passarella, Christine (July 31, 2022). "Harry Belafonte: Humanitarian, Social Justice Leader and Artist Extraordinaire". All About Jazz. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Simmons, Charlotte (April 25, 2023). "Actor, singer, and activist Harry Belafonte dies at 96". We Got This Covered. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Macdonald, Moira. "Movies | 'Sing Your Song' recounts Harry Belafonte's life". The Seattle Times. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Haygood, Wil (November 25, 2011). "Book review: 'My Song,' a memoir by Harry Belafonte". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Trott, Bill (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, who mixed music, acting, and activism, dies at 96 – NY Times". Nasdaq, Reuters.

- ^ a b Smith, Judith E (2014). "Multimedia Stardom and the Struggle for Racial Equality, 1955-1960". Becoming Belafonte: Black Artist, Public Radical (1st ed.). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 110–175. ISBN 978-0-292-76733-1 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ a b Puente, Maria (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, trailblazing singer, actor and activist, dies at 96". USA Today. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Ross, Steven J (2011). "Politics in Black and White: Harry Belafonte". Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 185–226 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ King, Martin Luther Jr. (2001). The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Grand Central. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-446-67650-2.

- ^ Settle, Tracy Wilson, WaTeasa Freeman, Alexis Clark & Jimmy. "Bigger than music: How Harry Belafonte contributed to Freedom Rides". The Leaf-Chronicle. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Belafonte, Harry; Shnayerson, Michael (2011). My Song: A Memoir. New York: Knopf. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-307-27226-3.

- ^ "Unicef Names Belafonte Good-Will Ambassador". The New York Times. March 9, 1987 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Harry Belafonte with Petula Clark – On The Path Of Glory on YouTube

- ^ "Tempest in TV Tube Is Sparked by Touch". Spokane Daily Chronicle. AP. March 5, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Bellafonte Hollers; Chrysler Says Everything's All Right". The Dispatch. Lexington, North Carolina. UPI. March 7, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Chrysler Rejects Charges Of Discrimination In Show". The Morning Record. Meriden–Wallingford, Connecticut. AP. March 7, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Belafonte says apologies can't change heart, color". The Afro American. March 16, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Belafonte Ire Brings Penalty: Chrysler Official Apologizes To Star". Toledo Blade. AP. March 11, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ New York Times (June 6, 2014). "Jackie Robinson and Nixon: Life and Death of a Political Friendship". New York Times Company. ISSN 1553-8095. ProQuest 1712316168 – via U.S. Newsstream, ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d e f "Watch Bobby Kennedy for President | Netflix Official Site". Netflix.com. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "Commercials – 1960 – Harry Belafonte". The Living Room Candidate. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Jet, October 1, 1964

- ^ Henderson Paul L, A. Scott; Thomas, Paul L.; Reese, Charles (2014). "8. James Baldwin: Artist as Activist and the Baldwin/Kennedy Secret Summit of 1963". James Baldwin: Challenging Authors. Vol. 5 (1st ed.). Rotterdam: Birkhäuser Boston. pp. 121–136. ISBN 9789462096172.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (April 17, 2012). "Barack Obama's father on colonial list of Kenyan students in US". The Guardian. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on Obama: 'He Plays the Game that He Plays Because He Sees No Threat from Evidencing Concerns for the Poor'". Democracy Now!. January 26, 2011.

- ^ Francis, Marquise (December 14, 2012). "Harry Belafonte: Obama should 'work like a third world dictator'". The Grio. MSNBC. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ "NAACP Image Awards | Harry Belafonte Speaks on Gun Control in Acceptance Speech | Feb 1, 2013". February 2, 2013. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ "REVOLUTION & RELIGION... A Dialogue Between Cornel West and Bob Avakian". YouTube. April 13, 2020.

- ^ Bernie 2016 (February 11, 2016), Harry Belafonte Endorses Bernie Sanders for President, retrieved February 11, 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Aneja, Arpita (January 21, 2017). "Gloria Steinem Harry Belafonte March on Washington VIDEO". Time. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte – The Sanders Institute". sandersinstitute.com.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on the AIDS crisis in Africa". CNN. June 26, 2001. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte urges all countries to end school fees, UNICEF reports | UN News". news.un.org. February 16, 2004. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte and prostate cancer". Phoenix5.org. April 21, 1997. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Willis, Mary P. (January 12, 2009). "Harry Belafonte, Humanitarian". AARP The Magazine. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte | UNICEF". Unicef.org. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Muhammad, Latifah; Dominic, Anthony (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, EGOT Winner and Activist, Dead at 96 | Entertainment Tonight". Etonline.com. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Advancement Project". Advancement Project. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Chiu, Kenneth (May 1, 2023). "Remembering Harry Belafonte". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "On Eve of Historic Windsor V. United States SCOTUS Case NYC Pride Announces 2013 Grand Marshals: Edith Windsor, Harry Belafonte, Earl Fowlkes to Lead March Down 5th Ave" (PDF). NYC Pride (Press release). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013.

- ^ "This week in history: Singer/activist Harry Belafonte thriving at 90". People's World. February 28, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Baker, Geoffrey (Fall 2005). "Hip Hop, Revolución! Nationalizing Rap in Cuba". Ethnomusicology. 49 (3): 368–402. JSTOR 20174403.

- ^ Levinson, Sandra (October 25, 2003). "An exclusive interview with Harry Belafonte on Cuba". Cuba Now. Retrieved October 25, 2003.

- ^ "Reception Honoring Oliver R. Tambo, President, The African National Congress (South Africa)". African Activist Archive. Matrix. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "Institute for Policy Studies: Trustees". Ips-dc.org. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b "Belafonte won't back down from Powell slave reference". CNN. October 14, 2002. Archived from the original on December 25, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Opinion: Powell's Mastery". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Powell, Rice Accused of Toeing the Line". Fox News. October 22, 2002.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on Bush, Iraq, Hurricane Katrina and Having His Conversations with Martin Luther King Wiretapped by the FBI". Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Venezuela plans to expand program to provide cheap heating oil to US poor". Taipei Times. October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Belafonte calls Bush 'greatest terrorist' – World news – Americas". NBC News. January 8, 2006. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Chavez Repeats 'Devil' Comment at Harlem Event". Fox News. September 21, 2006.

- ^ Thomson, Katherine (January 12, 2006). "Hillary's not wild about Harry". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Comments" (Press release). AARP.org. November 1, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on Bush, Iraq, Hurricane Katrina and Having His Conversations with Martin Luther King Wiretapped by the FBI". Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Brad (September 13, 2006). "Audience applauds Belafonte". The Daily Beacon. University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Politics-US: Belafonte on Thinking Outside the Ballot Box". Ipsnews.net. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Belafonte Blasts 'Gestapo' Security". Fox News. January 23, 2006.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (May 16, 2011). "Sing Your Song: Harry Belafonte on Art & Politics, Civil Rights & His Critique of President Obama". Democracy Now!. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "Ode aan Bonaire, een ongrijpbare liefde in de Caraïbische branding". ThePostOnline via Knipselkrant Curacao (in Dutch). Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Belnemproject". Amigoe via Delpher.nl (in Dutch). April 21, 1981. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Statuten Bel-Nem goedgekeurd". Amigoe di Curacao via Delpher.nl (in Dutch). June 29, 1966. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Bonaire, bevolkingscijfers per buurt". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (in Dutch). 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to the Anir Experience". Anir Foundation. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Gates Jr., Henry Louis (August 26, 1996). "Belafonte's Balancing Act", The New Yorker. Accessed March 19, 2019. "In 1953, enjoying his first real taste of affluence, Belafonte moved from Washington Heights into a white neighborhood in Elmhurst, Queens."

- ^ Hill, Erin (October 14, 2013). "Joan Collins Shares Steamy Details of Affairs with Harry Belafonte and Warren Beatty". Parade: Entertainment, Recipes, Health, Life, Holidays.

- ^ Zack, Ian (March 23, 2024). "Julie Robinson Belafonte, Dancer, Actress and Activist, Is Dead at 95". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ Bloom, Nate (November 17, 2011). "Jewish Stars 11/18". Cleveland Jewish News.

His second wife, dancer Julie Robinson, to whom he was married from 1958–2004, is Jewish. They had a daughter Gina, 50, and a son David, 54

- ^ Mottran, James (May 27, 2012). "Interview: Harry Belafonte, singer". The Scotsman.

- ^ Belafonte, Harry with Shnayerson, Michael (2012) My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance pp.192–193. New York: Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 9780307473424

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Fast Facts". CNN. July 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Ullmann, Liv (1998). Letter to My Grandchild. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-728-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Harry Belafonte – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "The Heart of Show Business". TMC. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Drei Lieder". Youtuber. March 3, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Harry Belafonte". TV Guide. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte, civil rights and entertainment giant, dies at 96". PBS. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "King: A Filmed Record ... Montgomery to Memphis". NMAAHC. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker". TV Guide. 1986. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte". BFI.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. (February 28, 2010). Harry Belafonte. Abc-Clio. ISBN 9781851097692. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (July 20, 2004). "Conakry Kas". Variety. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "'Kalipso Kralı' Harry Belafonte, 96 yaşında hayatını kaybetti". Kronos36. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Motherland". Mubi. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Sugar Hill Times". Video Detective. September 13, 1949. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Celebrating the Activism of Harry Belafonte". Ed Sullivan.com. November 20, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Remembering Harry Belafonte". CBS News. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Cast Archived August 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine (Harry Belafonte and the Belafonte Singers; Johnny Carson; Martha Raye). The Steve Allen Show Season 4 Episode 9.

- ^ "Tonight with Belafonte". TMC. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Roundtable on March on Washington". C-SPAN. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Goddard, Simon (April 2, 2018). "How Petula Clark and Harry Belafonte Fought Racism Arm in Arm". The Guardian. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour". Paley Center. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Nowakowski, Audrey; Hurbanis, Jack (April 25, 2023). "Documentary looks at Harry Belafonte's historic week hosting 'The Tonight Show' in 1968". WUWM. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "Harry Belafonte & Julie Andrews – A World in Music (1969)". December 8, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne – Harry & Lena Album Reviews, Songs & More". AllMusic.

- ^ "The Flip Wilson Show : Harry Belafonte, Burns and Schreiber (1973) – | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related". AllMovie.

- ^ Morris, Wesley (April 25, 2023). "Harry Belafonte, Folk Hero". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Hennes, Joe (April 25, 2023). "RIP Muppet Show Guest Harry Belafonte". ToughPigs.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte: Don't Stop The Carnival". Prod-www.tcm.com.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte | 'South Africa' | After Dark | Late-night live talk show | 1988". October 23, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Swing Vote". TVGuide.com.

- ^ "PB&J Otter – Season 2 Episode 26 – Video Detective". Videodetective.com. December 6, 1999.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte, activist and entertainer, dies at 96". Associated Press. April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "That's What I'm Talking About". May 13, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (August 21, 2006). "'When the Levees Broke': Spike Lee's Tales From a Broken City". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Grow, Kory (January 8, 2015). "Roger Waters, John Mellencamp Choose Interviewers for 'Speakeasy' TV Show". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte – Belafonte-En Gränslös Kväll På Operan (An Evening Without Borders at the Operahouse) Album Reviews, Songs & More". AllMusic.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte: Don't Stop the Carnival". TCM.

- ^ "John Murray Anderson's Almanac". Broadway World. 1953. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks (April 17, 1955). "3 for Tonight". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks (April 17, 1955). "3 for Tonight: Harry Belafonte and the Champions in an Informal". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Hall, Margaret (April 25, 2023). "Tony Winner Harry Belafonte Passes Away at 96". Playbill. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Belafonte at the Palace: Theatre Vault". Playbill. 1959. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "Harry Belafonte Tony Awards Wins and Nominations". Tonyawards.com. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "6th Annual Governors Awards | Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences". Oscars.org. October 28, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte". Television Academy.

- ^ "Theatre World Awards – Theatre World Awards". Theatreworldawards.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. June 19, 1954.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (March 14, 2020). "A Great Day-O for Black Culture". The New York Times. No. Arts pp C1, C3.

Further reading

[edit]- Sharlet, Jeff (2013). "Voice and Hammer". Virginia Quarterly Review (Fall 2013): 24–41. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- Smith, Judith. Becoming Belafonte: Black Artist, Public Radical. University of Texas Press, 2014. ISBN 9780292729148.

- Wise, James. Stars in Blue: Movie Actors in America's Sea Services. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 1557509379. OCLC 36824724.

External links

[edit]- SNCC Digital Gateway: Harry Belafonte, Documentary website created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, telling the story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee & grassroots organizing from the inside out

- Harry Belafonte at IMDb

- Harry Belafonte at the TCM Movie Database

- Harry Belafonte at the Internet Broadway Database

- Harry Belafonte at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Harry Belafonte discography at Discogs

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1927 births

- 2023 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- 21st-century American memoirists

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- American civil rights activists

- People from Harlem

- Male actors from Manhattan

- People from the Upper West Side

- American anti-war activists

- American folk singers

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American musicians of Jamaican descent

- American people of Dutch-Jewish descent

- American people of Martiniquais descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American people of Sephardic-Jewish descent

- American socialists

- American world music musicians

- Calypsonians

- Deaths from congestive heart failure

- Donaldson Award winners

- American feminist musicians

- George Washington Educational Campus alumni

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners

- Jubilee Records artists

- Kennedy Center honorees

- American male feminists

- American feminists

- Military personnel from New York City

- Musicians from Manhattan

- The New School alumni

- New York (state) socialists

- People from Elmhurst, Queens

- People from Washington Heights, Manhattan

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- RCA Victor artists

- Recipients of the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo

- Tony Award winners

- UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadors

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- United States Navy sailors

- Wolmer's Schools alumni