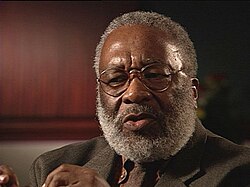

Vincent Harding

Vincent Harding | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Vincent Gordon Harding July 25, 1931 New York City, New York, US |

| Died | May 19, 2014 (aged 82) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Civil rights movement |

| Spouses |

|

| Ecclesiastical career | |

| Religion | Christianity (Mennonite) |

| Scholarly background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Doctoral advisor | Martin E. Marty |

| Scholarly work | |

| Discipline | History |

| Institutions | |

Vincent Gordon Harding (July 25, 1931 – May 19, 2014) was an African-American pastor, historian, and scholar of various topics with a focus on American religion and society. A social activist, he was perhaps best known for his work with and writings about Martin Luther King Jr., whom Harding knew personally. Besides having authored numerous books such as There Is A River, Hope and History, and Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero, he served as co-chairperson of the social unity group Veterans of Hope Project and as Professor of Religion and Social Transformation at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado.[1] When Harding died on May 19, 2014, his daughter, Rachel Elizabeth Harding, publicly eulogized him on the Veterans of Hope Project website.[2]

Education

[edit]Harding was born on July 25, 1931, in Harlem, New York,[3][4] and attended New York public schools, graduating from Morris High School in the Bronx in 1948. After finishing high school, he enrolled in the City College of New York, where he received a Bachelor of Arts in history in 1952.[5] The following year he graduated from Columbia University, where he earned a Master of Science degree in journalism. Harding served in the US Army from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 he received a Master of Arts degree in history at the University of Chicago. In 1965 he received his Doctor of Philosophy degree in history from the University of Chicago, where he was advised by Martin E. Marty.

Career

[edit]In 1960, Harding and his wife, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, moved to Atlanta, Georgia, to participate in the Southern Freedom Movement as representatives of the Mennonite Church. The Hardings co-founded Mennonite House, an interracial voluntary service center and movement gathering place in Atlanta. The couple traveled throughout the South in the early 1960s working as reconcilers, counselors and participants in the Movement, assisting the anti-segregation campaigns of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Vincent Harding occasionally drafted speeches for Martin Luther King Jr., including King's famous anti-Vietnam speech, "A Time to Break Silence", which King delivered on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York City, exactly a year before he was assassinated.[6][7]

Harding taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Spelman College, Temple University, Swarthmore College, and Pendle Hill Quaker Center for Study and Contemplation. In the months after King's 1968 assassination, Harding worked with Coretta Scott King to set up the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, and served as its first director.[8] During those same months in 1968, he worked with a group of scholars to set up Atlanta's Institute of the Black World.[8] He also became senior academic consultant for the PBS television series Eyes on the Prize.

Harding served as chairperson of the Veterans of Hope Project: A Center for the Study of Religion and Democratic Renewal, located at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado. He taught at Iliff as Professor of Religion and Social Transformation from 1981 to 2004.

Beliefs and activism

[edit]Harding was a devout Christian and believer in achieving racial and economic equality in the United States.[9] Harding was a Seventh-day Adventist pastor before becoming a Mennonite pastor.[10]

In January 2005, Harding remarked at the Christian liberal arts university Goshen College:

There's a lesson for us: If we lock up Martin Luther King, and make him unavailable for where we are now so we can keep ourselves comfortably distant from the realities he was trying to grapple with, we waste King. All of us are being called beyond those comfortable places where it's easy to be Christian. That's the key for the 21st century – to answer the voice within us, as it was within Martin, which says 'do something for somebody.' We can learn to play on locked pianos and to dream of worlds that do not yet exist.[9]

Writings

[edit]- Chapter 1 Widening the Circle: Experiments in Christian Discipleship

- African-American Christianity: Essays in History

- Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero

- Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement

- We Must Keep Going: Martin Luther King and the Future of America

- There Is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America

- Foreword to Wade in the Water: The Wisdom of the Spirituals, by Arthur C. Jones

- We Changed the World: African Americans, 1945–1970 (The Young Oxford History of African Americans, V. 9)

- A Certain Magnificence: Lyman Beecher and the Transformation of American Protestantism, 1775–1863 (Chicago Studies in the History of American Religion)

- Introduction to How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, by Walter Rodney, Howard University Press, editor Gregory S. Kearse

- Foreword to Jesus and the Disinherited, by Howard Thurman (Beacon Press, 1996)

- America Will Be! Conversations on Hope, Freedom, and Democracy with Daisaku Ikeda (Dialogue Path Press, 2013)

- "L'espoir de la démocratie", by Vincent Harding and Daisaku Ikeda (In French), (L'Harmattan, 2017, ISBN 978-2-343-11268-8)

- Introduction to Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community (Beacon press, re-released 2010)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Vincent Harding". Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ "Remembering Vincent Harding". Veterans of Hope. May 19, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ Johanna Shenk. Vincent Harding: ‘Don’t get weary though the way be long’ The Mennonite. Nov. 21, 2014.

- ^ Anders, Tisa (July 9, 2008). "Vincent Gordon Harding (1931-2014)". Black Past. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Harding, Vincent Gordon". The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. May 31, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Steve Chawkins (May 23, 2014). "Vincent Harding dies at 82; historian wrote controversial King speech". LA Times. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ Schudel, Matt (May 22, 2014). "Vincent Harding, author of Martin Luther King Jr's antiwar speech, dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ a b "Biography: Harding, Vincent Gordon". King Encyclopedia. Stanford University | Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. May 31, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Vincent Harding: King for the 21st century calls us to walk with Jesus", Goshen College, January 21, 2005.

- ^ Shearer, Tobin Miller (2015). "A Prophet Pushed Out: Vincent Harding and the Mennonites". Mennonite Life. 69. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Harding biography from Berkshire Publishing

- Harding biography from the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University

- Harding biography from Shift In Action (Institute of Noetic Sciences)

- Harding biography from Emory University

- Harding biography from the Iliff School of Theology

- "I've Known Rivers: The story of freedom movement leaders Rosemarie Freeney Harding and Vincent Harding" from Sojourners Magazine

External links

[edit]- Vincent Harding Papers, 1952-2014, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

- Vincent Harding at IMDb

- “Our Lives Can Be Signposts for What‘s Possible”, interview with Vincent Harding by Krista Tippett originally from the Civility, History, and Hope project as aired on On Being (audio + print transcript)

- Veterans of Hope Project

- Interview of Harding, from Religion and Ethics Newsweekly

- Interview of Harding on Democracy Now! (video, audio, and print transcript)

- Lecture by Harding on YouTube at Stanford University, video recorded October 25, 2007

- 1969 radio program, 1989 speech, and 1996 radio story on SoundTheology Use the Selected Speakers drop-down to choose Harding, Vincent.

Articles

[edit]- "Is America Possible?" by Vincent Harding, from On Being, Feb 24, 2011

- "Dangerous Spirituality" by Vincent Harding, from Sojourners Magazine

- "Martin Luther King and the Future of America" by Vincent Harding, from Cross Currents Magazine, Fall 1996, Vol. 46, Issue 3.

- "How Shall We Celebrate Martin Luther King's Birthday?" by Vincent and Rosemarie Harding, from Yes! Magazine

- "Freedom's Sacred Dance" by Vincent and Rosemarie Harding, from Yes! Magazine, October 27, 2000.

- 1931 births

- 2014 deaths

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Black studies scholars

- American biographers

- American historians of religion

- American Mennonites

- City College of New York alumni

- Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism alumni

- Former Seventh-day Adventists

- Historians from New York (state)

- Historians of African Americans

- Historians of the United States

- American male biographers

- Mennonite writers

- People from Harlem

- University of Chicago alumni

- Writers from Manhattan

- Historians of the civil rights movement

- Iliff School of Theology faculty