Mexican Revolution

| Mexican Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

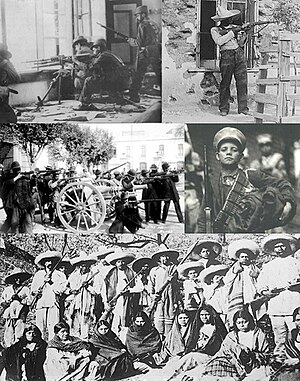

From left to right and top to bottom:

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| 1910–1911: | 1910–1911: | ||||||

| 1911–1913: | 1911–1913: | ||||||

| 1913–1914: | 1913–1914: | ||||||

| 1914–1915: | 1914–1915: | ||||||

| 1915–1920: |

1915–1920

Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| 1910–1911: | 1910–1911: | ||||||

1911–1913:

|

1911–1913:

| ||||||

1913–1914:

| 1913–1914: | ||||||

| 1914–1915: | 1914–1915: | ||||||

1915–1920:

|

1915–1920:

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

250,000–300,000 |

255,000–290,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

The Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Revolución mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920.[6][7][8] It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history".[9] It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its replacement by a revolutionary army,[10] and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940.[8][11] The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high.[12][13] The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly non-combatants.

Although the decades-long regime of President Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) was increasingly unpopular, there was no foreboding in 1910 that a revolution was about to break out.[12] The aging Díaz failed to find a controlled solution to presidential succession, resulting in a power struggle among competing elites and the middle classes, which occurred during a period of intense labor unrest, exemplified by the Cananea and Río Blanco strikes.[14] When wealthy northern landowner Francisco I. Madero challenged Díaz in the 1910 presidential election and Díaz jailed him, Madero called for an armed uprising against Díaz in the Plan of San Luis Potosí. Rebellions broke out first in Morelos and then to a much greater extent in northern Mexico. The Federal Army could not suppress the widespread uprisings, showing the military's weakness and encouraging the rebels.[15] Díaz resigned in May 1911 and went into exile, an interim government was installed until elections could be held, the Federal Army was retained, and revolutionary forces demobilized. The first phase of the Revolution was relatively bloodless and short-lived.

Madero was elected President, taking office in November 1911. He immediately faced the armed rebellion of Emiliano Zapata in Morelos, where peasants demanded rapid action on agrarian reform. Politically inexperienced, Madero's government was fragile, and further regional rebellions broke out. In February 1913, prominent army generals from the Díaz regime staged a coup d'etat in Mexico City, forcing Madero and Vice President Pino Suárez to resign. Days later, both men were assassinated by orders of the new President, Victoriano Huerta. This initiated a new and bloody phase of the Revolution, as a coalition of northerners opposed to the counter-revolutionary regime of Huerta, the Constitutionalist Army led by the Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza, entered the conflict. Zapata's forces continued their armed rebellion in Morelos. Huerta's regime lasted from February 1913 to July 1914, and the Federal Army was defeated by revolutionary armies. The revolutionary armies then fought each other, with the Constitutionalist faction under Carranza defeating the army of former ally Francisco "Pancho" Villa by the summer of 1915.

Carranza consolidated power and a new constitution was promulgated in February 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917 established universal male suffrage, promoted secularism, workers' rights, economic nationalism, and land reform, and enhanced the power of the federal government.[16] Carranza became President of Mexico in 1917, serving a term ending in 1920. He attempted to impose a civilian successor, prompting northern revolutionary generals to rebel. Carranza fled Mexico City and was killed. From 1920 to 1940, revolutionary generals held the office of president, each completing their terms (except from 1928-1934). This was a period when state power became more centralized, and revolutionary reform implemented, bringing the military under the civilian government's control.[17] The Revolution was a decade-long civil war, with new political leadership that gained power and legitimacy through their participation in revolutionary conflicts. The political party those leaders founded in 1929, which would become the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), ruled Mexico until the presidential election of 2000. When the Revolution ended, is not well defined, and even the conservative winner of the 2000 election, Vicente Fox, contended his election was heir to the 1910 democratic election of Francisco Madero, thereby claiming the heritage and legitimacy of the Revolution.[18]

Prelude to revolution: the Porfiriato and the 1910 election

[edit]| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

Liberal general and war veteran Porfirio Díaz came to the presidency of Mexico in 1876 and remained almost continuously in office until 1911 in an era now called Porfiriato.[19] Coming to power after a coup to oppose the re-election of Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, he could not run for re-election in 1880. His close ally, General Manuel González, was elected president (1880–1884). Díaz saw himself as indispensable, and after that interruption, he ran for the presidency again and served in office continuously until 1911. The constitution had been amended to allow unlimited presidential re-election.[20] During the Porfiriato, there were regular elections, widely considered sham exercises, marked by contentious irregularities.[20]

In his early years in the presidency, Díaz consolidated power by playing opposing factions against each other and by expanding the Rurales, an armed police militia directly under his control that seized land from local peasants. Peasants were forced to make futile attempts to win back their land through courts and petitions. By 1900, over ninety percent of Mexico's communal lands were sold, with an estimated 9.5 million peasants forced into the service of wealthy landowners or hacendados.[21] Diaz rigged elections, arguing that only he knew what was best for his country, and he enforced his belief with a strong hand. "Order and Progress" were the watchwords of his rule.[22]

Díaz's presidency was characterized by the promotion of industry and the development of infrastructure by opening the country to foreign investment. Díaz suppressed opposition and promoted stability to reassure foreign investors. Farmers and peasants both complained of oppression and exploitation. The situation was further exacerbated by the drought that lasted from 1907 to 1909.[23] The economy took a great leap during the Porfiriato, through the construction of factories, industries and infrastructure such as railroads and dams, as well as improving agriculture. Foreign investors bought large tracts of land to cultivate crops and range cattle for export. The cultivation of exportable goods such as coffee, tobacco, henequen for cordage, and sugar replaced the domestic production of wheat, corn and livestock that peasants had lived on.[24] Wealth, political power and access to education were concentrated among a handful of elite landholding families mainly of European and mixed descent. These hacendados controlled vast swaths of the country through their huge estates (for example, the Terrazas had one estate in Sonora that alone comprised more than a million acres). Many Mexicans became landless peasants laboring on these vast estates or industrial workers toiling long hours for low wages. Foreign companies (mostly from the United Kingdom, France, and the U.S.) also exercised influence in Mexico.[25]

Díaz and the military

[edit]Díaz had legitimacy as a leader through his battlefield accomplishments. He knew that the long tradition of military intervention in politics and its resistance to civilian control would prove challenging to his remaining in power. He set about curbing the power of the military, reining in provincial military chieftains, and making them subordinate to the central government. He contended with a whole new group of generals who had fought for the liberal cause and who expected rewards for their services. He systematically dealt with them, providing some rivals with opportunities to enrich themselves, ensuring the loyalty of others with high salaries, and others were bought off by rewards of landed estates and redirecting their political ambitions. Military rivals who did not accept the alternatives often rebelled and were crushed. It took him some 15 years to accomplish the transformation, reducing the army by 500 officers and 25 generals, creating an army subordinate to central power. He also created the military academy to train officers, but their training aimed to repel foreign invasions.[26] Díaz expanded the rural police force, the rurales as an elite guard, including many former bandits, under the direct control of the president.[27] With these forces, Díaz attempted to appease the Mexican countryside, led by a stable government that was nominally civilian, and the conditions to develop the country economically with the infusion of foreign investments.

During Díaz's long tenure in office, the Federal Army became overstaffed and top-heavy with officers, many of them elderly who last saw active military service against the French in the 1860s. Some 9,000 officers commanded the 25,000 rank-and-file on the books, with some 7,000 padding the rosters and nonexistent so that officers could receive the subsidies for the numbers they commanded. Officers used their positions for personal enrichment through salary and opportunities for graft. Although Mexicans had enthusiastically volunteered in the war against the French, the ranks were now filled by draftees. There was a vast gulf between officers and the lower ranks. "The officer corps epitomized everything the masses resented about the Díaz system."[28] With multiple rebellions breaking out in the wake of the fraudulent 1910 election, the military was unable to suppress them, revealing the regime's weakness and leading to Díaz's resignation in May 1911.[15]

Political system

[edit]

Although the Díaz regime was authoritarian and centralizing, it was not a military dictatorship. His first presidential cabinet was staffed with military men, but over successive terms as president, important posts were held by able and loyal civilians.[29] He did not create a personal dynasty, excluding family from the realms of power, although his nephew Félix attempted to seize power after the fall of the regime in 1911. Díaz created a political machine, first working with regional strongmen and bringing them into his regime, then replacing them with jefes políticos (political bosses) who were loyal to him. He skillfully managed political conflict and reined in tendencies toward autonomy. He appointed several military officers to state governorships, including General Bernardo Reyes, who became governor of the northern state of Nuevo León, but over the years military men were largely replaced by civilians loyal to Díaz.

As a military man himself, and one who had intervened directly in politics to seize the presidency in 1876, Díaz was acutely aware that the Federal Army could oppose him. He augmented the rurales, a police force created by Benito Juárez, making them his private armed force. The rurales were only 2,500 in number, as opposed to the 30,000 in the army and another 30,000 in the federal auxiliaries, irregulars and National Guard.[30] Despite their small numbers, the rurales were highly effective in controlling the countryside, especially along the 12,000 miles of railway lines. They were a mobile force, often sent on trains with their horses to put down rebellions in relatively remote areas of Mexico.[31]

The construction of railways had been transformative in Mexico (as well as elsewhere in Latin America), accelerating economic activity and increasing the power of the Mexican state. The isolation from the central government that many remote areas had enjoyed or suffered was ending. Telegraph lines constructed next to the railroad tracks meant instant communication between distant states and the capital.[32]

The political acumen and flexibility Díaz exhibited in his early years in office began to decline after 1900. He brought the state governors under his control, replacing them at will. The Federal Army, while large, was increasingly an ineffective force with aging leadership and troops conscripted into service. Díaz attempted the same kind of manipulation he executed with the Mexican political system with business interests, showing favoritism to European interests against those of the U.S.[33]

Rival interests, particularly those of the foreign powers with a presence in Mexico, further complicated an already complex system of favoritism.[25] As economic activity increased and industries thrived, industrial workers began organizing for better conditions. Díaz enacted policies that encouraged large landowners to intrude upon the villagers' land and water rights.[34] With the expansion of Mexican agriculture, landless peasants were forced to work for low wages or move to the cities. Peasant agriculture was under pressure as haciendas expanded, such as in the state of Morelos, just south of Mexico City, with its burgeoning sugar plantations. There was what one scholar has called "agrarian compression", in which "population growth intersected with land loss, declining wages and insecure tenancies to produce widespread economic deterioration", but the regions under the greatest stress were not the ones that rebelled.[35]

Opposition to Díaz

[edit]

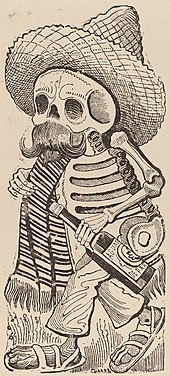

Díaz effectively suppressed strikes, rebellions, and political opposition until the early 1900s. Mexicans began to organize in opposition to Díaz, who had welcomed foreign capital and capitalists, suppressed nascent labor unions, and consistently moved against peasants as agriculture flourished.[36] In 1905 the group of Mexican intellectuals and political agitators who had created the Mexican Liberal Party (Partido Liberal de México) drew up a radical program of reform, specifically addressing what they considered to be the worst aspects of the Díaz regime. Most prominent in the PLM were Ricardo Flores Magón and his two brothers, Enrique and Jesús. They, along with Luis Cabrera and Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, were connected to the anti-Díaz publication El Hijo del Ahuizote. Political cartoons by José Guadalupe Posada lampooned politicians and cultural elites with mordant humor, portraying them as skeletons. The Liberal Party of Mexico founded the anti-Díaz anarchist newspaper Regeneración, which appeared in both Spanish and English. In exile in the United States, Práxedis Guerrero began publishing an anti-Díaz newspaper, Alba Roja ("Red Dawn"), in San Francisco, California. Although leftist groups were small, they became influential through their publications, articulating their opposition to the Díaz regime. Francisco Bulnes described these men as the "true authors" of the Mexican Revolution for agitating the masses.[37] As the 1910 election approached, Francisco I. Madero, an emerging political figure and member of one of Mexico's richest families, funded the newspaper Anti-Reelectionista, in opposition to the continual re-election of Díaz.

Organized labor conducted strikes for better wages and just treatment. Demands for better labor conditions were central to the Liberal Party program, drawn up in 1905. Mexican copper miners in the northern state of Sonora took action in the 1906 Cananea strike. Starting June 1, 1906, 5,400 miners began organizing labor strikes.[38] Among other grievances, they were paid less than U.S. nationals working in the mines.[39] In the state of Veracruz, textile workers rioted in January 1907 at the huge Río Blanco factory, the world's largest, protesting against unfair labor practices. They were paid in credit that could be used only at the company store, binding them to the company.[40]

These strikes were ruthlessly suppressed, with factory owners receiving support from government forces. In the Cananea strike, mine owner William Cornell Greene received support from Díaz's rurales in Sonora as well as Arizona Rangers called in from across the U.S. border.[39] This Arizona Rangers were ordered to use violence to combat labor unrest.[41] In the state of Veracruz, the Mexican army gunned down Rio Blanco textile workers and put the bodies on train cars that transported them to Veracruz, "where the bodies were dumped in the harbor as food for sharks".[42]

Since the press was censored in Mexico under Díaz, little was published that was critical of the regime. Newspapers barely reported on the Rio Blanco textile strike, the Cananea strike or harsh labor practices on plantations in Oaxaca and Yucatán. Leftist Mexican opponents of the Díaz regime, such as Ricardo Flores Magón and Práxedis Guerrero, went into exile in the relative safety of the United States, but cooperation between the U.S. government and Díaz's agents resulted in the arrest of some radicals.[43]

Presidential succession in 1910

[edit]

Díaz had ruled continuously since 1884. The question of presidential succession was an issue as early as 1900 when he turned 70.[44] Díaz re-established the office of vice president in 1906, choosing Ramón Corral. Rather than managing political succession, Díaz marginalized Corral, keeping him away from decision-making.[45] Díaz publicly announced in an interview with journalist James Creelman for Pearson's Magazine that he would not run in the 1910 election. At age 80, this set the scene for a possible peaceful transition in the presidency. It set off a flurry of political activity. To the dismay of potential candidates to replace him, he reversed himself and ran again. His later reversal on retiring from the presidency set off tremendous activity among opposition groups.

Díaz seems to have initially considered Finance Minister José Yves Limantour as his successor. Limantour was a key member of the Científicos, the circle of technocratic advisers steeped in positivist political science. Another potential successor was General Bernardo Reyes, Díaz's Minister of War, who also served as governor of Nuevo León. Reyes, an opponent of the Científicos, was a moderate reformer with a considerable base of support.[44] Díaz became concerned about him as a rival and forced him to resign from his cabinet. He attempted to marginalize Reyes by sending him on a "military mission" to Europe,[45] distancing him from Mexico and potential political supporters. "The potential challenge from Reyes would remain one of Díaz's political obsessions through the rest of the decade, which ultimately blinded him to the danger of the challenge of Francisco Madero's anti-re-electionist campaign."[45]

In 1910, Francisco I. Madero, a young man from a wealthy landowning family in the northern state of Coahuila, announced his intent to challenge Díaz for the presidency in the next election, under the banner of the Anti-Reelectionist Party. Madero chose as his running mate Francisco Vázquez Gómez, a physician who had opposed Díaz.[46] Madero campaigned vigorously and effectively. To ensure Madero did not win, Díaz had him jailed before the election. He escaped and fled for a short period to San Antonio, Texas.[47] Díaz was announced the winner of the election by a "landslide".

End of the Porfiriato: November 1910 – May 1911

[edit]

On 5 October 1910, Madero issued a "letter from jail", known as the Plan de San Luis Potosí, with its main slogan Sufragio Efectivo, No Re-elección ("effective voting, no re-election"). It declared the Díaz presidency illegal and called for a revolt against him, starting on 20 November 1910. Madero's political plan did not outline a major socioeconomic revolution but offered hopes of change for many disadvantaged Mexicans. The plan strongly opposed militarism in Mexico as it was constituted under Díaz, calling on Federal Army generals to resign before true democracy could prevail in Mexico. Madero realized he needed a revolutionary armed force, enticing men to join with the promise of formal rank, and encouraged Federales to join the revolutionary forces with the promise of promotion.[48]

Madero's plan was aimed at fomenting a popular uprising against Díaz, but he also understood that the support of the United States and U.S. financiers would be of crucial importance in undermining the regime. The rich and powerful Madero family drew on its resources to make regime change possible, with Madero's brother Gustavo A. Madero hiring, in October 1910, the firm of Washington lawyer Sherburne Hopkins, the "world's best rigger of Latin-American revolutions", to encourage support in the U.S.[30] A strategy to discredit Díaz with U.S. business and the U.S. government achieved some success, with Standard Oil representatives engaging in talks with Gustavo Madero. More importantly, the U.S. government "bent neutrality laws for the revolutionaries".[49]

In late 1910, revolutionary movements arose in response to Madero's Plan de San Luis Potosí. Still, their ultimate success resulted from the Federal Army's weakness and inability to suppress them.[50] Madero's vague promises of land reform attracted many peasants throughout the country. Spontaneous rebellions arose in which ordinary farm laborers, miners and other working-class Mexicans, along with much of the country's population of indigenous peoples, fought Díaz's forces with some success. Madero attracted the forces of rebel leaders such as Pascual Orozco, Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata, and Venustiano Carranza. A young and able revolutionary, Orozco—along with Chihuahua Governor Abraham González—formed a powerful military union in the north and, although they were not especially committed to Madero, took Mexicali and Chihuahua City. These victories encouraged alliances with other revolutionary leaders, including Villa. Against Madero's wishes, Orozco and Villa fought for and won Ciudad Juárez, bordering El Paso, Texas, on the south side of the Rio Grande. Madero's call to action had unanticipated results, such as the Magonista rebellion of 1911 in Baja California.[51]

Interim presidency: May–November 1911

[edit]

With the Federal Army defeated in several battles with irregular, voluntary forces, Díaz's government began negotiations with the revolutionaries in the north. In historian Edwin Lieuwen's assessment, "Victors always attribute their success to their own heroic deeds and superior fighting abilities ... In the spring of 1911, armed bands under self-appointed chiefs arose all over the republic, drove Díaz officials from the vicinity, seized money and stamps, and staked out spheres of local authority. Towns, cities, and the countryside passed into the hands of the Maderistas."[50]

Díaz sued for peace with Madero, who himself did not want a prolonged and bloody conflict. The result was the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, signed on 21 May 1911. The signed treaty stated that Díaz would abdicate the presidency along with his vice president, Ramón Corral, by the end of May 1911 to be replaced by an interim president, Francisco León de la Barra, until elections were held. Díaz and his family and a number of top supporters were allowed to go into exile.[52] When Díaz left for exile in Paris, he was reported as saying, "Madero has unleashed a tiger; let us see if he can control it."[53]

With Díaz in exile and new elections to be called in October, the power structure of the old regime remained firmly in place. Francisco León de la Barra became interim president, pending an election to be held in October 1911. Madero considered De la Barra an acceptable figure for the interim presidency since he was not a Científico or politician, but rather a Catholic lawyer and diplomat.[54] He appeared to be a moderate, but the German ambassador to Mexico, Paul von Hintze, who associated with the Interim President, said of him that "De la Barra wants to accommodate himself with dignity to the inevitable advance of the ex-revolutionary influence, while accelerating the widespread collapse of the Madero party."[55] The Federal Army, despite its numerous defeats by the revolutionaries, remained intact as the government's force. Madero called on revolutionary fighters to lay down their arms and demobilize, which Emiliano Zapata and the revolutionaries in Morelos refused to do.

The cabinet of De la Barra and the Mexican congress was filled with supporters of the Díaz regime. Madero campaigned vigorously for the presidency during this interim period, but revolutionaries who had supported him and brought about Díaz's resignation were dismayed that the sweeping reforms they sought were not immediately instituted. He did introduce some progressive reforms, including improved funding for rural schools; promoting some aspects of agrarian reform to increase the amount of productive land; labor reforms including workman's compensation and the eight-hour day; but also defended the right of the government to intervene in strikes. According to historian Peter V. N. Henderson, De la Barra's and congress's actions "suggests that few Porfirians wished to return to the status quo of the dictatorship. Rather, the thoughtful, progressive members of the Porfirian meritocracy recognized the need for change."[56] De la Barra's government sent General Victoriano Huerta to fight in Morelos against the Zapatistas, burning villages and wreaking havoc. His actions drove a wedge between Zapata and Madero, which widened when Madero was inaugurated as president.[57] Zapata remained in arms continuously until his assassination in 1919.

Madero won the 1911 election decisively and was inaugurated as president in November 1911, but his movement had lost crucial momentum and revolutionary supporters in the months of the Interim Presidency and left in place the Federal Army.

Madero presidency: November 1911 – February 1913

[edit]

Madero had drawn some loyal and militarily adept supporters who brought down the Díaz regime by force of arms. Madero himself was not a natural soldier, and his decision to dismiss the revolutionary forces that brought him to power isolated him politically. He was an inexperienced politician, who had never held office before. He firmly held to democratic ideals, which many consider evidence of naivete. His election as president in October 1911 raised high expectations among many Mexicans for positive change. The Treaty of Ciudad Juárez guaranteed that the essential structure of the Díaz regime, including the Federal Army, was kept in place.[58] Madero fervently held to his position that Mexico needed real democracy, which included regime change by free elections, a free press, and the right of labor to organize and strike.

The rebels who brought him to power were demobilized and Madero called on these men of action to return to civilian life. According to a story told by Pancho Villa, a leader who had defeated Díaz's army and forced his resignation and exile, he told Madero at a banquet in Ciudad Juárez in 1911, "You [Madero], sir, have destroyed the revolution ... It's simple: this bunch of dandies have made a fool of you, and this will eventually cost us our necks, yours included."[59] Ignoring the warning, Madero increasingly relied on the Federal Army as armed rebellions broke out in Mexico in 1911–12, with particularly threatening insurrections led by Emiliano Zapata in Morelos and Pascual Orozco in the north. Both Zapata and Orozco had led revolts that had put pressure on Díaz to resign, and both felt betrayed by Madero once he became president.

The press embraced its newfound freedom and Madero became a target of its criticism. Organized labor, which had been suppressed under Díaz, could and did stage strikes, which foreign entrepreneurs saw as threatening their interests. Although there had been labor unrest under Díaz, labor's new freedom to organize also came with anti-American currents.[60] The anarcho-syndicalist Casa del Obrero Mundial (House of the World Worker) was founded in September 1912 by Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Manuel Sarabia, and Lázaro Gutiérrez de Lara and served as a center of agitation and propaganda, but it was not a formal labor union.[61][62]

Political parties proliferated. One of the most important was the National Catholic Party, which in several regions of the country was particularly strong.[63] Several Catholic newspapers were in circulation during the Madero era, including El País and La Nación, only to be later suppressed under the Victoriano Huerta regime (1913–1914).[64] Under Díaz relations between the Roman Catholic Church and the Mexican government were stable, with the anticlerical laws of the Mexican Constitution of 1857 remaining in place, but not enforced, so conflict was muted.[65] During Madero's presidency, Church-state conflict was channeled peacefully.[65] The National Catholic Party became an important political opposition force during the Madero presidency.[66] In the June 1912 congressional elections, "militarily quiescent states ... the Catholic Party (PCN) did conspicuously well."[67] During that period, the Catholic Association of Mexican Youth (ACJM) was founded. Although the National Catholic Party was an opposition party to the Madero regime, "Madero clearly welcomed the emergence of a kind of two-party system (Catholic and liberal); he encouraged Catholic political involvement, echoing the exhortations of the episcopate."[68] What was emerging during the Madero regime was "Díaz's old policy of Church-state detente was being continued, perhaps more rapidly and on surer foundations."[66] The Catholic Church in Mexico was working within the new democratic system promoted by Madero, but it had its interests to promote, some of which were the forces of the old conservative Church, while the new, progressive Church supporting social Catholicism of the 1891 papal encyclical Rerum Novarum was also a current. When Madero was overthrown in February 1913 by counter-revolutionaries, the conservative wing of the Church supported the coup.[69]

Madero did not have the experience or the ideological inclination to reward men who had helped bring him to power. Some revolutionary leaders expected personal rewards, such as Pascual Orozco of Chihuahua. Others wanted major reforms, most especially Emiliano Zapata and Andrés Molina Enríquez, who had long worked for land reform.[70] Madero met personally with Zapata, telling the guerrilla leader that the agrarian question needed careful study. His meaning was clear: Madero, a member of a rich northern hacendado family, was not about to implement comprehensive agrarian reform for aggrieved peasants.

In response to this lack of action, Zapata promulgated the Plan de Ayala in November 1911, declaring himself in rebellion against Madero. He renewed guerrilla warfare in the state of Morelos. Madero sent the Federal Army to deal with Zapata, unsuccessfully. Zapata remained true to the demands of the Plan de Ayala and in rebellion against every central government up until his assassination by an agent of President Venustiano Carranza in 1919.

The northern revolutionary General Pascual Orozco, a leader in taking Ciudad Juárez, had expected to become governor of Chihuahua. In 1911, although Orozco was "the man of the hour", Madero gave the governorship instead to Abraham González, a respectable revolutionary, with the explanation that Orozco had not reached the legal age to serve as governor, a tactic that was "a useful constitutional alibi for thwarting the ambitions of young, popular, revolutionary leaders".[71] Madero had put Orozco in charge of the large force of rurales in Chihuahua, but to a gifted revolutionary fighter who had helped bring about Díaz's fall, Madero's reward was insulting. After Madero refused to agree to social reforms calling for better working hours, pay, and conditions, Orozco organized his army, the Orozquistas, also called the Colorados ("Red Flaggers") and issued his Plan Orozquista on 25 March 1912, enumerating why he was rising in revolt against Madero.[72]

In April 1912, Madero dispatched General Victoriano Huerta of the Federal Army to put down Orozco's dangerous revolt. Madero had kept the army intact as an institution, using it to put down domestic rebellions against his regime. Huerta was a professional soldier and continued to serve in the army under the new commander-in-chief. Huerta's loyalty lay with General Bernardo Reyes rather than with the civilian Madero. In 1912, under pressure from his cabinet, Madero called on Huerta to suppress Orozco's rebellion. With Huerta's success against Orozco, he emerged as a powerful figure for conservative forces opposing the Madero regime.[73] During the Orozco revolt, the governor of Chihuahua mobilized the state militia to support the Federal Army. Pancho Villa, now a colonel in the militia, was called up at this time. In mid-April, at the head of 400 irregular troops, he joined the forces commanded by Huerta. Huerta, however, viewed Villa as an ambitious competitor. During a visit to Huerta's headquarters in June 1912, after an incident in which he refused to return a number of stolen horses, Villa was imprisoned on charges of insubordination and robbery and sentenced to death.[74] Raúl Madero, the President's brother, intervened to save Villa's life. Jailed in Mexico City, Villa escaped and fled to the United States, later to return and play a major role in the civil wars of 1913–1915.

There were other rebellions, one led by Bernardo Reyes and another by Félix Díaz, nephew of the former president, that were quickly put down and the generals jailed. They were both in Mexico City prisons and, despite their geographical separation, they were able to foment yet another rebellion in February 1913. This period came to be known as the Ten Tragic Days (La Decena Trágica), which ended with Madero's resignation and assassination and Huerta assuming the presidency. Although Madero had reason to distrust Victoriano Huerta, Madero placed him in charge of suppressing the Mexico City revolt as interim commander. He did not know that Huerta had been invited to join the conspiracy, but had initially held back.[73] During the fighting that took place in the capital, the civilian population was subjected to artillery exchanges, street fighting and economic disruption, perhaps deliberately caused by the coupists to demonstrate that Madero was unable to keep order.[75]

A military coup overthrows Madero: 9–22 February 1913

[edit]

The Madero presidency was unravelling, to no one's surprise except perhaps Madero's, whose support continued to deteriorate, even among his political allies. Madero's supporters in congress before the coup, the so-called Renovadores ("the renewers"), criticized him, saying, "The revolution is heading toward collapse and is pulling the government to which it gave rise down with it, for the simple reason that it is not governing with revolutionaries. Compromises and concessions to the supporters of the old [Díaz] regime are the main causes of the unsettling situation in which the government that emerged from the revolution finds itself ... The regime appears relentlessly bent on suicide."[77]

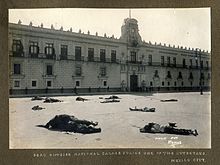

Huerta, formally in charge of the defense of Madero's regime, allowed the rebels to hold the armory in Mexico City—the Ciudadela—while he consolidated his political power. He changed allegiance from Madero to the rebels under Félix Díaz (Bernardo Reyes having been killed on the first day of the open armed conflict). U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who had done all he could to undermine U.S. confidence in Madero's presidency, brokered the Pact of the Embassy, which formalized the alliance between Félix Díaz and Huerta, with the backing of the United States.[78] Huerta was to become provisional president following the resignations of Madero and his vice president, José María Pino Suárez. Rather than being sent into exile with their families, the two were murdered while being transported to prison—a shocking event, but one that did not prevent the Huerta regime's recognition by most world governments, with the notable exception of the U.S.

Historian Friedrich Katz considers Madero's retention of the Federal Army, which was defeated by the revolutionary forces and resulted in Díaz's resignation, "was the basic cause of his fall". His failure is also attributable to "the failure of the social class to which he belonged and whose interests he considered to be identical to those of Mexico: the liberal hacendados" (owners of large estates).[79] Madero had created no political organization that could survive his death and had alienated and demobilized the revolutionary fighters who had helped bring him to power. In the aftermath of his assassination and Huerta's seizure of power via a military coup, former revolutionaries had no formal organization through which to raise opposition to Huerta.[80]

Huerta regime and civil war: February 1913 – July 1914

[edit]

Madero's "martyrdom accomplished what he was unable to do while alive: unite all the revolutionists under one banner."[81] Within 16 months, revolutionary armies defeated the Federal Army and the Huerta regime fell. Like Porfirio Díaz, Huerta went into exile. The Federal Army was disbanded, leaving only revolutionary military forces.

Upon taking power, Huerta had moved swiftly to consolidate his hold in the North, having learned the lesson from Díaz's fall that the north was a crucial region to hold. Within a month of the coup, rebellions began to spread throughout Mexico, most prominently led by the governor of the state of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, along with Pablo González. Huerta expected state governors to fall into line with the new government. But Carranza and Abraham González, Governor of Chihuahua did not. Carranza issued the Plan of Guadalupe, a strictly political plan to reject the legitimacy of the Huerta government, and called on revolutionaries to take up arms. Revolutionaries who had brought Madero to power only to be dismissed in favor of the Federal Army eagerly responded to the call, most prominently Pancho Villa. Alvaro Obregón of Sonora, a successful rancher and businessman who had not participated in the Madero revolution, now joined the revolutionary forces in the north, the Constitutionalist Army under the Primer Jefe ("First Chief") Venustiano Carranza. Huerta had Governor González arrested and murdered, for fear he would foment rebellion.[80] When northern General Pancho Villa became governor of Chihuahua in 1914, following the defeat of Huerta, he located González's bones and had them reburied with full honors. In Morelos, Emiliano Zapata continued his rebellion under the Plan of Ayala (while expunging the name of counter-revolutionary Pascual Orozco from it), calling for the expropriation of land and redistribution to peasants. Huerta offered peace to Zapata, who rejected it.[82] The Huerta government was thus challenged by revolutionary forces in the north of Mexico and the strategic state of Morelos, just south of the capital.

Huerta's presidency is usually characterized as a dictatorship. From the point of view of revolutionaries at the time and the construction of historical memory of the Revolution, it is without any positive aspects. "Despite recent attempts to portray Victoriano Huerta as a reformer, there is little question that he was a self-serving dictator."[83] There are few biographies of Huerta, but one strongly asserts that Huerta should not be labeled simply as a counter-revolutionary,[84] arguing that his regime consisted of two distinct periods: from the coup in February 1913 up to October 1913. During that time he attempted to legitimize his regime and demonstrate its legality by pursuing reformist policies; and after October 1913, when he dropped all attempts to rule within a legal framework and began murdering political opponents while battling revolutionary forces that had united in opposition to his regime.[85]

Supporting the Huerta regime initially were business interests in Mexico, both foreign and domestic; landed elites; the Roman Catholic Church; and the German and British governments. The U.S. President Woodrow Wilson did not recognize the Huerta regime, since it had come to power by coup.[86] Huerta and Carranza were in contact for two weeks immediately after the February coup, but they did not come to an agreement. Carranza then declared himself opposed to Huerta and became the leader of the anti-Huerta forces in the north.[87] Huerta gained the support of revolutionary general Pascual Orozco, who had helped topple the Díaz regime, then rebelled against Madero because of his lack of action on agrarian issues. Huerta's first cabinet comprised men who had supported the February 1913 Pact of the Embassy, among them some who had supported Madero, such as Jesús Flores Magón; supporters of General Bernardo Reyes; supporters of Félix Díaz; and former Interim President Francisco León de la Barra.[88]

During the counter-revolutionary regime of Huerta, the Catholic Church in Mexico initially supported him. "The Church represented a force for reaction, especially in the countryside."[65] However, when Huerta cracked down on political parties and conservative opposition, he had "Gabriel Somellera, president of the [National] Catholic Party arrested; La Nación, which, like other Catholic papers, had protested Congress's dissolution and the rigged elections [of October 1913], locked horns with the official press and was finally closed down. El País, the main Catholic newspaper, survived for a time."[64]

Huerta was even able to briefly muster the support of Andrés Molina Enríquez, author of The Great National Problems (Los grandes problemas nacionales), a key work urging land reform in Mexico.[89] Huerta was seemingly deeply concerned with the issue of land reform, since it was a persistent spur of peasant unrest. Specifically, he moved to restore "ejido lands to the Yaquis and Mayos of Sonora and [advanced] proposals for distribution of government lands to small-scale farmers."[90][91] When Huerta refused to move faster on land reform, Molina Enríquez disavowed the regime in June 1913,[92] later going on to advise the 1917 constitutional convention on land reform.

U.S. President Taft left the decision of whether to recognize the new government up to the incoming president, Woodrow Wilson. Despite the urging of U.S. ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who had played a key role in the coup d'état, President Wilson not only declined to recognize Huerta's government but first supplanted the ambassador by sending his "personal representative" John Lind, a progressive who sympathized with the Mexican revolutionaries, and the president recalled Ambassador Wilson. The United States lifted the arms embargo imposed by Taft in order to supply weapons to the landlocked rebels; while under the complete embargo Huerta had still been able to receive shipments from the British by sea. Wilson urged European powers to not recognize Huerta's government, and attempted to persuade Huerta to call prompt elections "and not present himself as a candidate".[93] The United States offered Mexico a loan on the condition that Huerta accept the proposal. He refused. Lind "clearly threatened a military intervention in case the demands were not met".[93]

In the summer of 1913, Mexican conservatives who had supported Huerta sought a constitutionally-elected, civilian alternative to Huerta, brought together in a body called the National Unifying Junta.[94] Political parties proliferated in this period, a sign that democracy had taken hold, and there were 26 by the time of the October congressional elections. From Huerta's point of view, the fragmentation of the conservative political landscape strengthened his own position. For the country's conservative elite, "there was a growing disillusionment with Huerta, and disgust at his strong-arm methods."[95] Huerta closed the legislature on 26 October 1913, having the army surround its building and arresting congressmen perceived to be hostile to his regime. Despite that, congressional elections went ahead, but given that congress was dissolved and some members were in jail, opposition candidates' fervor disappeared. The sham election "brought home to [Woodrow] Wilson's administration the fatuity of relying on elections to demonstrate genuine democracy."[96] The October 1913 elections were the end of any pretension to constitutional rule in Mexico, with civilian political activity banned.[97] Prominent Catholics were arrested and Catholic newspapers were suppressed.[64]

Huerta militarized Mexico to a greater extent than it already was. When Huerta seized power in 1913, the army had on the books approximately 50,000 men, but Huerta mandated the number rise to 150,000, then 200,000 and, finally in spring 1914, 250,000.[64] Raising that number of men in so short a time would not occur with volunteers, and the army resorted to the leva, forced conscription. The revolutionary forces had no problem with voluntary recruitment.[98] Most Mexican men avoided government conscription at all costs and the ones dragooned into the forces were sent to areas far away from home and were reluctant to fight. Conscripts deserted, mutinied and attacked and murdered their officers.[99]

In April 1914 U.S. opposition to Huerta culminated in the seizure and occupation of the port of Veracruz by U.S. Marines and sailors. Initially intended to prevent a German merchant vessel from delivering a shipment of arms to the Huerta regime, the muddled operation evolved into a seven-month stalemate resulting in the death of 193 Mexican soldiers, 19 U.S. servicemen and an unknown number of civilians. The German ship landed its cargo—largely U.S.-made rifles—in a deal brokered by U.S. businessmen (at a different port). U.S. forces eventually left Veracruz in the hands of the Carrancistas, but with lasting damage to U.S.-Mexican relations.[100][101]

In Mexico's south, Zapata took Chilpancingo, Guerrero in mid-March; he followed this soon afterward with the capture of the Pacific coast port of Acapulco; Iguala; Taxco; and Buenavista de Cuellar. He confronted the federal garrisons in Morelos, the majority of which defected to him with their weapons. Finally he moved against the capital, by sending his subordinates into Mexico state.[102]

Constitutionalist forces made major gains against the Federal Army. In early 1914 Pancho Villa had moved against the Federal Army in the border town of Ojinaga, Chihuahua, sending the federal soldiers fleeing to Fort Bliss, in the U.S. state of New Mexico. In mid-March he took Torreón, a well-defended railway hub city. After bitter fighting for the hills surrounding Torreón, and later point-blank bombardment, on April 3 Villa's troops entered the devastated city. The Federal Army made a last stand at San Pedro de las Colonias, only to be undone by squabbling between the two commanding officers, General Velasco and General Maas, over who had the higher rank. As of mid-April, Mexico City sat undefended before Constitutionalist forces under Villa.[102] Obregón moved south from Sonora along the Pacific Coast. When his way was blocked by federal gunboats, Obregón attacked these boats with an airplane, an early use of an airplane for military purposes. In early July he defeated federal troops at Orendain, Jalisco, leaving 8,000 federals dead and capturing a large trove of armaments. He was now in a position to arrive at Mexico City ahead of Villa, who was diverted by orders from Carranza to take Saltillo.[102] Carranza, the civilian First Chief, and Villa, the bold and successful commander of the Division of the North, were on the verge of splitting. Obregón, the other highly successful Constitutionalist general, sought to keep the northern coalition intact.

The Federal Army's defeats caused Huerta's position to continue to deteriorate and in mid-July 1914, he stepped down and fled to the Gulf Coast port of Puerto México, seeking to get himself and his family out of Mexico rather than face the fate of Madero. He turned to the German government, which had generally supported his presidency. The Germans were not eager to allow him to be transported into exile on one of their ships, but relented. Huerta carried "roughly half a million marks in gold with him" as well as paper currency and checks.[103] In exile, Huerta sought to return to Mexico via the United States. U.S. authorities arrested him and he was imprisoned in Fort Bliss, Texas. He died in January 1916, six months after going into exile.[104]

Huerta's resignation marked the end of an era. The Federal Army, a spectacularly ineffective fighting force against the revolutionaries, ceased to exist.[105] The revolutionary factions that had united in opposition to Huerta's regime now faced a new political landscape with the counter-revolutionaries decisively defeated. The revolutionary armies now contended for power and a new era of civil war began after an attempt at an agreement among the winners at a Convention of Aguascalientes.

Meeting of the winners, then civil war: 1914–1915

[edit]

With Huerta's ouster in July 1914 and the dissolution of the Federal Army in August, the revolutionary factions agreed to meet and make "a last-ditch effort to avert more intense warfare than that which unseated Huerta".[106] Commander of the Division of the North, Pancho Villa, and the Division of the Northeast, Pablo González had drawn up the Pact of Torreón in early July, pushing for a more radical agenda than Carranza's Plan of Guadalupe. It also called for a meeting of revolutionary generals to decide Mexico's political future.

Carranza called for a meeting in October 1914 Mexico City, which he now controlled with Obregón, but other revolutionaries opposed to Carranza's influence successfully moved the venue to Aguascalientes. The Convention of Aguascalientes did not, in fact, reconcile the various victorious factions in the Mexican Revolution. The break between Carranza and Villa became definitive during the Convention. "Carranza spurned it, and Villa effectively hijacked it. Mexico's lesser caudillos were forced to choose" between those two forces.[107] It was a brief pause in revolutionary violence before another all-out period of civil war ensued.

Carranza had expected to be confirmed in his position as First Chief of revolutionary forces, but his supporters "lost control of the proceedings".[108] Opposition to Carranza was strongest in areas where there were popular and fierce demands for reform, particularly in Chihuahua where Villa was powerful, and in Morelos where Zapata held sway.[109] The Convention of Aguascalientes brought that opposition out in an open forum.

The revolutionary generals of the Convention called on Carranza to resign executive power. Although he agreed to do so, he laid out conditions for it. He would resign if both Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, his main rivals for power, would resign and go into exile, and that there should be a so-called pre-constitutionalist government "that would take charge of carrying out the social and political reforms the country needs before a fully constitutional government is re-established."[110]

Rather than First Chief Carranza being named president of Mexico at the convention, General Eulalio Gutiérrez was chosen for a term of 20 days. The Convention declared Carranza in rebellion against it. Civil war resumed, this time between revolutionary armies that had fought in a united cause to oust Huerta in 1913–1914. During the Convention, Constitutionalist General Álvaro Obregón had attempted to be a moderating force and had been the one to convey the Convention's call for Carranza to resign.

The lines were now drawn. When the Convention forces declared Carranza in rebellion against it, Obregón supported Carranza rather than Villa and Zapata. Villa and Zapata went into a loose alliance. Their forces moved separately on Mexico City, and took it when Carranza's forces evacuated it in December 1914 for Veracruz. The famous picture of Zapata and Villa in the National Palace, with Villa sitting in the presidential chair, is a classic image of the Revolution. Villa is reported to have said to Zapata that the presidential chair "is too big for us".[108]

In practice, the alliance between Villa and Zapata as the Army of the Convention did not function beyond this initial victory against the Constitutionalists. Villa and Zapata left the capital, with Zapata returning to his southern stronghold in Morelos, where he continued to engage in warfare under the Plan of Ayala.[108] Lacking a firm center of power and leadership, the Convention government was plagued by instability. Villa was the real power emerging from the Convention, and he prepared to strengthen his position by winning a decisive victory against the Constitutionalist Army.

Villa had a well-earned reputation as a fierce and successful general, and the combination of forces arrayed against Carranza by Villa, other northern generals and Zapata was larger than the Constitutionalist Army, so it was not at all clear that Carranza's faction would prevail. He did have the advantage of the loyalty of General Álvaro Obregón. Despite Obregón's moderating actions at the Convention of Aguascalientes, even trying to persuade Carranza to resign his position, he ultimately sided with Carranza.[111]

Another advantage of Carranza's position was the Constitutionalists' control of Veracruz, even though the United States still occupied it. The United States had concluded that both Villa and Zapata were too radical and hostile to its interests and sided with the moderate Carranza in the factional fighting.[112] The U.S. timed its exit from Veracruz, brokered at the Niagara Falls peace conference, to benefit Carranza and allowed munitions to flow to the Constitutionalists. The U.S. granted Carranza's government diplomatic recognition in October 1915.

The rival armies of Villa and Obregón clashed in April 1915 in the Battle of Celaya, which lasted from the sixth to the 15th. The frontal cavalry charges of Villa's forces were met by the shrewd, modern military tactics of Obregón. The victory of the Constitutionalists was complete, and Carranza emerged as the political leader of Mexico with a victorious army to keep him in that position. Villa retreated north. Carranza and the Constitutionalists consolidated their position as the winning faction, with Zapata remaining a threat until his assassination in 1919. Villa also remained a threat to the Constitutionalists, complicating their relationship with the United States when elements of Villa's forces raided Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916, prompting the U.S. to launch a punitive expedition into Mexico in an unsuccessful attempt to capture him.

Constitutionalists in power under Carranza: 1915–1920

[edit]

Carranza's 1913 Plan of Guadalupe was narrowly political, designed to unite the anti-Huerta forces in the north. But once Huerta was ousted, the Federal Army dissolved, and former Constitutionalist Pancho Villa defeated, Carranza sought to consolidate his position. The Constitutionalists retook Mexico City, which had been held by the Zapatistas, and held it permanently. He did not take the title of provisional or interim President of Mexico, since in doing so he would have been ineligible to become the constitutional president. Until the promulgation of the 1917 Constitution was framed as the "preconstitutional government".

In October 1915, the U.S. recognized Carranza's government as the de facto ruling power, following Obregón's victories. This gave Carranza's Constitutionalists legitimacy internationally and access to the legal flow of arms from the U.S. The Carranza government still had active opponents, including Villa, who retreated north.[113] Zapata remained active in the south, even though he was losing support, Zapata remained a threat to the Carranza regime until his assassination by order of Carranza on 10 April 1919.[114] Disorder and violence in the countryside was largely due to anti-Carranza forces, but banditry as well as military and police misconduct contributed to the unsettled situation. The government's inability to keep order gave an opening to supporters of the old order headed by Félix Díaz (nephew of former President Porfirio Diaz). Some 36 generals of the dissolved Federal Army stood with Díaz.

The Constitutionalist Army was renamed the "Mexican National Army" and Carranza sent some of its most able generals to eliminate threats. In Morelos, he sent General Pablo González to fight Zapata's Liberating Army of the South.[115] Morelos was very close to Mexico City, so Zapata's control of it and parts of the adjacent state of Puebla made Carranza's government vulnerable. Constitutionalist Army soldiers assassinated Zapata in an ambush in 1919, after their commanding officer tricked Zapata by pretending that he intended to defect to Zapata's side. Carranza sent General Francisco Murguía and General Manuel M. Diéguez to track down and eliminate Villa, but they were unsuccessful. They did capture and execute one of Villa's top men, General Felipe Angeles, the only general of the old Federal Army to join the revolutionaries.[116] Revolutionary generals asserted their "right to rule", having been victorious in the Revolution, but "they ruled in a manner which was a credit neither to themselves, their institution, nor the Carranza government. More often than not, they were predatory, venal, cruel and corrupt."[117] The system of central government control over states that Díaz had created over decades had broken down during the revolutionary fighting. Autonomous fiefdoms arose in which governors simply ignored orders by the Carranza government. One of these was Governor of Sonora, General Plutarco Elías Calles, who later joined in the 1920 successful coup against Carranza.[118]

The 1914 Pact of Torreón had contained far more radical language and promises of land reform and support for peasants and workers than Carranza's original plan. Carranza issued the "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe", which for the first time promised significant reform. He also issued an agrarian reform law in 1915, drafted by Luis Cabrera, sanctioning the return of all village lands illegally seized in contravention of an 1856 law passed under Benito Juárez. The Carranza reform declared village lands were to be divided among individuals, aiming at creating a class of small holders, and not to revive the old structure of communities of communal landholders. In practice, land was transferred not to villagers, but rather redistributed to Constitutional army generals, and created new large-scale enterprises as rewards to the victorious military leaders.[119]

Carranza did not move on land reform, despite his rhetoric. Rather, he returned confiscated estates to their owners.[120] Not only did he oppose large-scale land reform, he vetoed laws that would have increased agricultural production by giving peasants temporary access to lands not under cultivation.[121] In places where peasants had fought for land reform, Carranza's policy was to repress them and deny their demands. In the southeast, where hacienda owners held strong, Carranza sent the most radical of his supporters, Francisco Múgica in Tabasco and Salvador Alvarado in Yucatan, to mobilize peasants and be a counterweight to the hacienda owners.[122] After taking control of Yucatán in 1915, Salvador Alvarado organized a large Socialist Party and carried out extensive land reform. He confiscated the large landed estates and redistributed the land in smaller plots to the liberated peasants.[123] Maximo Castillo, a revolutionary brigadier general from Chihuahua was frustrated by the slow pace of land reform under the Madero presidency. He ordered the subdivision of six haciendas belonging to Luis Terrazas, which were given to sharecroppers and tenants.[124]

Carranza's relationship with the United States had initially benefited from its recognition of his government, with the Constitutionalist Army being able to buy arms. In 1915 and early 1916, there is evidence that Carranza was seeking a loan from the U.S. with the backing of U.S. bankers and a formal alliance with the U.S. Mexican nationalists in Mexico were seeking a stronger stance against the colossus of the north, by taxing foreign holdings and limiting their influence. Villa's raid against Columbus, New Mexico in March 1916, ended the possibility of a closer relationship with the U.S.[125] Under heavy pressure from public opinion in the U.S. to punish the attackers (stoked mainly by the papers of ultra-conservative publisher William Randolph Hearst, who owned a large estate in Mexico), U.S. President Woodrow Wilson sent General John J. Pershing and around 5,000 troops into Mexico in an attempt to capture Villa.[126]

The U.S. Army intervention, known as the Punitive Expedition, was limited to the western Sierras of Chihuahua. From the Mexican perspective, as much as Carranza sought the elimination of his rival Villa, but as a Mexican nationalist he could not countenance the extended U.S. incursion into its sovereign territory. Villa knew the inhospitable terrain intimately and operating with guerrilla tactics, he had little trouble evading his U.S. Army pursuers. Villa was deeply entrenched in the mountains of northern Mexico and knew the terrain too well to be captured. U.S. General John J. Pershing could not continue with his unsuccessful mission; declaring victory the troops returned to the U.S. after nearly a year. They were shortly thereafter deployed to Europe when the U.S. entered World War I on the side of the Allies. The Punitive Mission not only damaged the fragile United States-Mexico relationship, but also caused a rise in anti-American sentiment among the Mexicans.[127] Carranza asserted Mexican sovereignty and forced the U.S. to withdraw in 1917.

With the outbreak of World War I in Europe in 1914, foreign powers with significant economic and strategic interests in Mexico—particularly the U.S., Great Britain and Germany—made efforts to sway Mexico to their side, but Mexico maintained a policy of neutrality. In the Zimmermann Telegram, a coded cable from the German government to Carranza's government, Germany attempted to draw Mexico into war with the United States, which was itself neutral at the time. Germany hoped to draw U.S. troops from deployment to Europe and as a reward in the event of a German victory to return the territory lost to Mexico to the U.S. in the Mexican–American War. Carranza did not pursue this policy, but the leaking of the telegram pushed the U.S. into war against Germany in 1917.

1917 Constitution

[edit]

The Constitutionalist Army fought in the name of the 1857 Constitution promulgated by liberals during the Reform era, sparking a decade-long armed conflict between liberals and conservatives. In contrast, the 1917 Constitution came at the culmination of revolutionary struggle. Drafting a new constitution was not a given at the outbreak of the Revolution. Carranza's 1913 Plan of Guadalupe was a narrow political plan to unite Mexicans against the Huerta regime and named Carranza as the head of the Constitutionalist Army. Increasingly revolutionaries called for radical reform. Carranza had consolidated power and his advisers persuaded him that a new constitution would better accomplish incorporating major reforms than a piecemeal revision of the 1857 constitution.[128]

In 1916 Carranza was only acting president at the time, and the expectation was to hold presidential elections. He called for a constituent congress to draft a new document based on liberal and revolutionary principles. Labor had supported the Constitutionalists and Red Battalions had fought against the Zapatistas, the peasant revolutionaries of Morelos. As revolutionary violence subsided in 1916, leaders of the Constitutionalist faction met in Querétaro to revise the 1857 constitution. The delegates were elected by jurisdiction and population, with the exclusion of those who served the Huerta regime, continued to follow Villa after the split with Carranza, as well as Zapatistas. The election of delegates was to frame the creation of the new constitution as the result of popular participation. Carranza provided a draft revision for the delegates to consider.

Once the convention was in session after disputes about delegates, delegates reviewed Carranza's draft constitution. That document was a minor revision of the 1857 constitution and included none of the social, economic, and political demands for which revolutionary forces fought and died. The convention was divided between conservatives, mostly politicians who had supported Madero and then Carranza, and progressives, who were soldiers who had fought in revolutionary battles. The progressives, deemed radical Jacobins by the conservatives, "sought to integrate deep political and social reforms into the political structure of the country."[129] making principles for which many of the revolutionaries had fought into law.

The Mexican Constitution of 1917 was strongly nationalist, giving the government the power to expropriate foreign ownership of resources and enabling land reform (Article 27). It also had a strong code protecting organized labor (Article 123) and extended state power over the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico in its role in education (Article 3).

Villistas and Zapatistas were excluded from the Constituent Congress, but their political challenge pushed the delegates to radicalize the Constitution, which in turn was far more radical than Carranza himself.[130] While he was elected constitutional president in 1917, he did not implement its most revolutionary elements, particularly those dealing with land reform. Carranza came from the old Porfirian landowning class and was repulsed by peasant demand for redistribution of land and their expectation that land seized would not revert to their previous owners.

Although revolutionary generals were not part formal delegates to the convention, Álvaro Obregón indirectly, then directly, sided with the progressives against Carranza. In historian Frank Tannenbaum's assessment, "The Constitution was written by the soldiers of the Revolution, not by the lawyers, who were there [at the convention], but were generally in opposition."[131] The constitution was drafted and ratified quickly, in February 1917. In December 1916, Villa had captured the major northern city of Torreón, with Obregón especially realizing that Villa was a continuing threat to the Constitutionalist regime. Zapata and his peasant followers in Morelos also never put down their guns and remained a threat to the government in Mexico City. Incorporating radical aspects of Villa's program and the Zapatistas' Plan of Ayala, the constitution became a way to outflank the two opposing revolutionary factions.

Carranza was elected president under the new constitution, and once formally in office, largely ignored or actively undermined the more radical aspects of the constitution. Obregón returned to Sonora and began building a power base that would launch his presidential campaign in 1919, which included the new labor organization headed by Luis N. Morones, the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM). Carranza increasingly lost support of labor, crushing strikes against his government. Carranza did not move forward on land reform, fueling increasing opposition from peasants. In an attempt to suppress the continuing armed opposition conflict in Morelos, Carranza sent General Pablo González with troops. Going further, Carranza ordered the assassination of Emiliano Zapata in 1919. It was a huge blow, but Zapatista General Genovevo de la O continued to lead the armed struggle there.

Emiliano Zapata and the Revolution in Morelos

[edit]

From the late Porfiriato until his assassination by an agent of President Carranza in 1919, Emiliano Zapata played an important role in the Mexican Revolution, the only revolutionary of first rank from southern Mexico.[132] His home territory in Morelos was of strategic importance just south of Mexico City. Of the revolutionary factions, it was the most homogeneous, with most fighters being free peasants and only few peons on haciendas. With no industry to speak of in Morelos, there were no industrial workers in the movement and no middle-class participants. A few intellectuals supported the Zapatistas. The Zapatistas' armed opposition movement just south of the capital needed to be heeded by those in power in Mexico City. Unlike northern Mexico, close to the U.S. border and access to arms sales from there, the Zapatista territory in Morelos was geographically isolated from access to arms. The Zapatistas did not appeal for support to international interests nor play a role in international politics the way Pancho Villa, the other major populist leader, did. The movement's goal was for land reform in Morelos and restoration of the rights of communities. The Zapatistas were divided into guerrilla fighting forces that joined together for major battles before returning to their home villages. Zapata was not a peasant himself but led peasants in his home state in regionally concentrated warfare to regain village lands and return to subsistence agriculture. Morelos was the only region where land reform was enacted during the years of fighting.[133]

Zapata initially supported Madero, since his Plan de San Luis Potosí had promised land reform. But Madero negotiated a settlement with the Díaz regime that continued its power. Once elected in November 1911, Madero did not move on land reform, prompting Zapata to rebel against him and draft the Plan of Ayala (1911).[134][135]

With the overthrow of Madero and murder, Zapata disavowed his previous admiration of Pascual Orozco and directed warfare against the Huerta government, as did northern states of Mexico in the Constitutionalist movement, but Zapata did not ally or coordinate with it. With the defeat of Huerta in July 1914, Zapata loosely allied with Pancho Villa, who had split from Venustiano Carranza and the Constitutionalist Army. The loose Zapata-Villa alliance lasted until Obregón decisively defeated Villa in a series of battles in 1915, including the Battle of Celaya. Zapata continued to oppose the Constitutionalists, but lost support in his own area and attempted to entice defectors back to his movement. That was a fatal error. He was ambushed and killed on 10 April 1919 by agents of now President Venustiano Carranza.[136] Photos were taken of his corpse, demonstrating that he had indeed been killed.

Although Zapata was assassinated, the agrarian reforms that peasants themselves enacted in Morelos were impossible to reverse. The central government came to terms with that state of affairs. Zapata had fought for land and for those who tilled it in Morelos and succeeded. His credentials as a steadfast revolutionary made him an enduring hero of the Revolution. His name and image were invoked in the 1994 uprising in Chiapas, with the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.

The last successful coup: 1920

[edit]

Even as Carranza's political authority was waning, he attempted to impose a political nobody, Mexico's ambassador to the U.S., Ignacio Bonillas, as his successor. Under the Plan of Agua Prieta, a triumvirate of Sonoran generals, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta, with elements from the military and labor supporters in the CROM, rose in successful rebellion against Carranza, the last successful coup of the revolution.[137] Carranza fled Mexico City by train toward Veracruz, but continued on horseback and died in an ambush, perhaps an assassination, but also possibly by suicide. Carranza's attempt to impose his choice was considered a betrayal of the Revolution and his remains were not placed in the Monument to the Revolution until 1942.[138]

"Obregón and the Sonorans, the architects of Carranza's rise and fall, shared his hard headed opportunism, but they displayed a better grasp of the mechanisms of popular mobilization, allied to social reform, that would form the bases of a durable revolutionary regime after 1920."[120] The interim government of Adolfo de la Huerta negotiated Pancho Villa's surrender in 1920, rewarding him with an hacienda where he lived in peace until he floated political interest in the 1924 election. Villa was assassinated in July 1923.[139] Álvaro Obregón was elected president in October 1920, the first of a string of revolutionary generals – Calles, Rodríguez, Cárdenas, and Ávila Camacho—to hold the presidency until 1946, when Miguel Alemán, the son of a revolutionary general, was elected.

Consolidation of the Revolution: 1920–1940

[edit]The period 1920–1940 is generally considered to be one of revolutionary consolidation, with the leaders seeking to return Mexico to the level of development it had reached in 1910, but under new parameters of state control. Authoritarian tendencies rather than Liberal democratic principles characterized the period, with generals of the revolution holding the presidency and designating their successors.[140] Revolutionary generals continued to revolt against the new political arrangements, particularly at the juncture of an election. General Adolfo de la Huerta rose in rebellion in 1923, contesting Obregón's choice of Calles as his successor; Generals Arnulfo Gómez and Francisco Serrano revolted in 1928, contesting Obregón's bid for a second term as president; and General José Gonzalo Escobar revolted in 1929 against Calles, who remained a power behind the presidency with the assassination of Obregón in 1928. All these revolts were unsuccessful. In the late 1920s, anticlerical provisions of the 1917 Constitution were stringently enforced, leading to a major grassroots uprising against the government, the bloody Cristero War that lasted from 1926 to 1929. Although the period is characterized as a consolidation of the Revolution, who ruled Mexico and the policies the government pursued were met with violence.[141]

Sonoran generals in the presidency: 1920–1928

[edit]

There is no consensus when the Revolution ended, but the majority of scholars consider the 1920s and 1930s as being on the continuum of revolutionary change.[142][143] [8]The end date of revolutionary consolidation has also been set at 1946, with the last general serving as president and the political party morphing into the Institutional Revolutionary Party.[144]

In 1920, Sonoran revolutionary general Álvaro Obregón was elected President of Mexico and inaugurated in December 1920, following the coup engineered by him and revolutionary generals Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta. The coup was supported by other revolutionary generals against the civilian Carranza attempting to impose another civilian, Ignacio Bonillas as his successor. Obregón did not have to deal with two major revolutionary leaders. De la Huerta managed to persuade revolutionary general Pancho Villa to lay down his arms against the regime in return for a large estate in Durango, in northern Mexico. Carranza's agents had assassinated Emiliano Zapata in 1919, removing a consistent and effective opponent. Some counterrevolutionaries in Chiapas laid down their arms. The only pro-Carranza governor to resist the regime change was Esteban Cantú in Baja California, suppressed by northern revolutionary general Abelardo Rodríguez,[145] later to become president of Mexico. Although the 1917 Constitution was not fully implemented and parts of the country were still controlled by local strongmen, caciques, Obregón's presidency did begin consolidation of parts of the revolutionary agenda, including expanded rights of labor and the peasantry.

Obregón was a pragmatist and not an ideologue, so that domestically he had to appeal to both the left and the right to ensure Mexico would not fall back into civil war. Securing labor rights built on Obregón's existing relationship with urban labor. The Constitutionists had made an alliance with labor during the revolution, mobilizing the Red Battalions against Zapata's and Villa's force. This alliance continued under Obregón's and Calles's terms as president. Obregón also focused on land reform. He had governors in various states push forward the reforms promised in the 1917 constitution. These were, however, quite limited. Former Zapatistas still had strong influence in the post-revolutionary government, so most of the reforms began in Morelos, the birthplace of the Zapatista movement.[146]

Obregón's government was faced with the need for stabilizing Mexico after a decade of civil war. With the revolutionary armies having defeated the old federal army, Obregón now dealt with military leaders who were used to wielding power violently. Enticing them to leave the political arena in exchange for material rewards was one tactic. De la Huerta had already successfully used it with Pancho Villa. Not trusting Villa to remain on the sidelines, Obregón had him assassinated in 1923.[147] In 1923 De la Huerta rebelled against Obregón and his choice of Calles as his successor as president, leading to a split in the military. The rebellion was suppressed and Obregón began to professionalize the military, reduced the number of troops by half, and forced officers to retire. Obregón (1920–24) followed by Calles (1924–28) viewed bringing the armed forces under state control as essential to stabilizing Mexico.[148] Downsizing the military meant that state funds were freed up for other priorities, especially education.[149] Obregón's Minister of Education, José Vasconcelos, initiated innovative broad educational and cultural programs.