History of capitalism

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic history |

|---|

| Particular histories of |

| Economics events |

| Prominent examples |

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production. This is generally taken to imply the moral permissibility of profit, free trade, capital accumulation, voluntary exchange, wage labor, etc. Its emergence, evolution, and spread are the subjects of extensive research and debate. Debates sometimes focus on how to bring substantive historical data to bear on key questions.[1] Key parameters of debate include: the extent to which capitalism is natural, versus the extent to which it arises from specific historical circumstances; whether its origins lie in towns and trade or in rural property relations; the role of class conflict; the role of the state; the extent to which capitalism is a distinctively European innovation; its relationship with European imperialism; whether technological change is a driver or merely a secondary byproduct of capitalism; and whether or not it is the most beneficial way to organize human societies.[2]

Agrarian capitalism

[edit]Crisis of the 14th century

[edit]

William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas, 01923

According to some historians,[3] the modern capitalist system originated in the "crisis of the Late Middle Ages", a conflict between the land-owning aristocracy and the agricultural producers, or serfs. Manorial arrangements inhibited the development of capitalism in a number of ways. Serfs had obligations to produce for lords and therefore had no interest in technological innovation; they also had no interest in cooperating with one another because they produced to sustain their own families. The lords who owned the land[citation needed] relied on force to guarantee that they received sufficient food. Because lords were not producing to sell on the market, there was no competitive pressure for them to innovate. Finally, because lords expanded their power and wealth through military means, they spent their wealth on military equipment or on conspicuous consumption that helped foster alliances with other lords; they had no incentive to invest in developing new productive technologies.[4]

The demographic crisis of the 14th century upset this arrangement. This crisis had several causes: agricultural productivity reached its technological limitations and stopped growing, bad weather led to the Great Famine of 1315–1317, and the Black Death of 1348–1350 led to a population crash. These factors led to a decline in agricultural production. In response, feudal lords sought to expand agricultural production by extending their domains through warfare; therefore they demanded more tribute from their serfs to pay for military expenses. In England, many serfs rebelled. Some moved to towns, some bought land, and some entered into favorable contracts to rent lands from lords who needed to repopulate their estates.[5]

In effect, feudalism began to lay some of the foundations necessary for the development of mercantilism, a precursor of capitalism. Feudalism lasted from the medieval period through the 16th century. Feudal manors were almost entirely self-sufficient, and therefore limited the role of the market. This stifled any incipient tendency towards capitalism. However, the relatively sudden emergence of new technologies and discoveries, particularly in agriculture[6] and exploration, facilitated the growth of capitalism. The most important development at the end of feudalism[citation needed] was the emergence of what Robert Degan calls "the dichotomy between wage earners and capitalist merchants".[7] The competitive nature meant there are always winners and losers, and this became clear as feudalism evolved into mercantilism, an economic system characterized by the private or corporate ownership of capital goods, investments determined by private decisions, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods determined mainly by competition in a free market.[citation needed]

Enclosure

[edit]

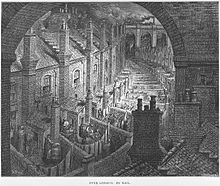

England in the 16th century was already a centralized state, in which much of the feudal order of Medieval Europe had been swept away. This centralization was strengthened by a good system of roads and a disproportionately large capital city, London.[8] The capital acted as a central market for the entire country, creating a large internal market for goods, in contrast to the fragmented feudal holdings that prevailed in most parts of the Continent. The economic foundations of the agricultural system were also beginning to diverge substantially; the manorial system had broken down by this time, and land began to be concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. The system put pressure on both the landlords and the tenants to increase agricultural productivity to create profit. The weakened coercive power of the aristocracy to extract peasant surpluses encouraged them to try out better methods. The tenants also had an incentive to improve their methods to succeed in an increasingly competitive labour market. Land rents had moved away from the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation, and were becoming directly subject to economic market forces.

An important aspect of this process of change was the enclosure[9] of the common land previously held in the open field system where peasants had traditional rights, such as mowing meadows for hay and grazing livestock. Once enclosed, these uses of the land became restricted to the owner, and it ceased to be land for commons. The process of enclosure began to be a widespread feature of the English agricultural landscape during the 16th century. By the 19th century, unenclosed commons had become largely restricted to rough pasture in mountainous areas and to relatively small parts of the lowlands.

Marxist and neo-Marxist historians argue that rich landowners used their control of state processes to appropriate public land for their private benefit. This created a landless working class that provided the labour required in the new industries developing in the north of England. For example: "In agriculture the years between 1760 and 1820 are the years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common rights are lost".[10] "Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery".[11] Anthropologist Jason Hickel notes that this process of enclosure led to myriad peasant revolts, among them Kett's Rebellion and the Midland Revolt, which culminated in violent repression and executions.[12]

Other scholars[13] argue that the better-off members of the European peasantry encouraged and participated actively in enclosure, seeking to end the perpetual poverty of subsistence farming. "We should be careful not to ascribe to [enclosure] developments that were the consequence of a much broader and more complex process of historical change."[14] "[T]he impact of eighteenth and nineteenth century enclosure has been grossly exaggerated...."[15]

Merchant capitalism and mercantilism

[edit]Precedents

[edit]

While trade has existed since early in human history, it was not capitalism.[16] The earliest recorded activity of long-distance profit-seeking merchants can be traced to the old Assyrian merchants active in Mesopotamia the 2nd millennium BCE.[17] The Roman Empire developed more advanced forms of commerce, and similarly widespread networks existed in Islamic nations. However, capitalism took shape in Europe in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

An early emergence of commerce occurred on monastic estates in Italy and France, but in particular in the independent Italian city-states during the late Middle Ages, such as Florence, Genoa and Venice. Those states pioneered innovative financial instruments such as bills of exchange and banking practices that facilitated long-distance trade. The competitive nature of these city-states fostered a spirit of innovation and risk-taking, laying the groundwork for capitalism's core principles of private ownership, market competition, and profit-seeking behavior. The economic prowess of the Italian city-states during this time not only fueled its own prosperity but also contributed significantly to the spread of capitalist ideas and practices throughout Europe and beyond.[18][19]

Emergence

[edit]Modern capitalism resembles some elements of mercantilism in the early modern period between the 16th and 18th centuries.[20][21] Early evidence for mercantilist practices appears in early modern Venice, Genoa, and Pisa over the Mediterranean trade in bullion. The region of mercantilism's real birth, however, was the Atlantic Ocean.[22]

England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the Elizabethan Era. An early statement on national balance of trade appeared in Discourse of the Common Weal of this Realm of England, 1549: "We must always take heed that we buy no more from strangers than we sell them, for so should we impoverish ourselves and enrich them."[23][full citation needed] The period featured various but often disjointed efforts by the court of Queen Elizabeth to develop a naval and merchant fleet capable of challenging the Spanish stranglehold on trade and of expanding the growth of bullion at home. Elizabeth promoted the Trade and Navigation Acts in Parliament and issued orders to her navy for the protection and promotion of English shipping.

These efforts organized national resources sufficiently in the defense of England against the far larger and more powerful Spanish Empire, and in turn paved the foundation for establishing a global empire in the 19th century.[citation needed] The authors noted most for establishing the English mercantilist system include Gerard de Malynes and Thomas Mun, who first articulated the Elizabethan System. The latter's England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure gave a systematic and coherent explanation of the concept of balance of trade. It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.[24] Mercantile doctrines were further developed by Josiah Child. Numerous French authors helped to cement French policy around mercantilism in the 17th century. French mercantilism was best articulated by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (in office, 1665–1683), although his policies were greatly liberalised under Napoleon.

Doctrines

[edit]Under mercantilism, European merchants, backed by state controls, subsidies, and monopolies, made most of their profits from buying and selling goods. In the words of Francis Bacon, the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices..."[25] Similar practices of economic regimentation had begun earlier in medieval towns. However, under mercantilism, given the contemporaneous rise of absolutism, the state superseded the local guilds as the regulator of the economy.

Among the major tenets of mercantilist theory was bullionism, a doctrine stressing the importance of accumulating precious metals. Mercantilists argued that a state should export more goods than it imported so that foreigners would have to pay the difference in precious metals. Mercantilists asserted that only raw materials that could not be extracted at home should be imported. They promoted the idea that government subsidies, such as granting monopolies and protective tariffs, were necessary to encourage home production of manufactured goods.

Proponents of mercantilism emphasized state power and overseas conquest as the principal aim of economic policy. If a state could not supply its own raw materials, according to the mercantilists, it should acquire colonies from which they could be extracted. Colonies constituted not only sources of raw materials but also markets for finished products. Because it was not in the interests of the state to allow competition, to help the mercantilists, colonies should be prevented from engaging in manufacturing and trading with foreign powers.

Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist production methods.[26] Noting the various pre-capitalist features of mercantilism, Karl Polanyi argued that "mercantilism, with all its tendency toward commercialization, never attacked the safeguards which protected [the] two basic elements of production – labor and land – from becoming the elements of commerce." Thus mercantilist regulation was more akin to feudalism than capitalism. According to Polanyi, "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date."[27]

Chartered trading companies

[edit]

The Muscovy Company was the first major chartered joint stock English trading company. It was established in 1555 with a monopoly on trade between England and Muscovy. It was an offshoot of the earlier Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, founded in 1551 by Richard Chancellor, Sebastian Cabot and Sir Hugh Willoughby to locate the Northeast Passage to China to allow trade. This was the precursor to a type of business that would soon flourish in England, the Dutch Republic and elsewhere.

The British East India Company (1600) and the Dutch East India Company (1602) launched an era of large state chartered trading companies.[28][29] These companies were characterized by their monopoly on trade, granted by letters patent provided by the state. Recognized as chartered joint-stock companies by the state, these companies enjoyed lawmaking, military, and treaty-making privileges.[30] Characterized by its colonial and expansionary powers by states, powerful nation-states sought to accumulate precious metals, and military conflicts arose.[28] During this era, merchants, who had previously traded on their own, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a return on investment.

Industrial capitalism

[edit]

Mercantilism declined in Great Britain in the mid-18th century, when a new group of economic theorists, led by Adam Smith, challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines, such as that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state. However, mercantilism continued in less developed economies, such as Prussia and Russia, with their much younger manufacturing bases.

The mid-18th century gave rise to industrial capitalism, made possible by (1) the accumulation of vast amounts of capital under the merchant phase of capitalism and its investment in machinery, and (2) the fact that the enclosures meant that Britain had a large population of people with no access to subsistence agriculture, who needed to buy basic commodities via the market, ensuring a mass consumer market.[31] Industrial capitalism, which Marx dated from the last third of the 18th century, marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex division of labor between and within work processes and the routinization of work tasks. Industrial capitalism finally established the global domination of the capitalist mode of production.[20]

During the resulting Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant as a dominant actor in the capitalist system, which led to the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of artisans, guilds, and journeymen. Also during this period, capitalism transformed relations between the British landowning gentry and peasants, giving rise to the production of cash crops for the market rather than for subsistence on a feudal manor. The surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture.

There is an activate debate on the role of the Atlantic slavery in the emergence of industrial capitalism.[32] Eric Williams (1944) argued on Capitalism and Slavery about the crucial role of plantation slavery in the growth of industrial capitalism, since both happened in similar time periods. Harvey (2019) wrote that "A flagship of the industrial revolution, the Lancashire mills and their 465,000 textile workers, was entirely reliant [in the 1860s] on the labour of three million cotton slaves in the American Deep South."[33]

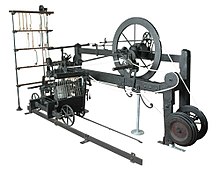

Industrial Revolution

[edit]The productivity gains of capitalist production began a sustained and unprecedented increase at the turn of the 19th century, in a process commonly referred to as the Industrial Revolution. Starting in about 1760 in England, there was a steady transition to new manufacturing processes in a variety of industries, including going from hand production methods to machine production, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power and the development of machine tools. It also included the change from wood and other bio-fuels to coal.

In textile manufacturing, mechanized cotton spinning powered by steam or water increased the output of a worker by a factor of about 1000, due to the application of James Hargreaves' spinning jenny, Richard Arkwright's water frame, Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule and other inventions. The power loom increased the output of a worker by a factor of over 40.[34] The cotton gin increased the productivity of removing seed from cotton by a factor of 50. Large gains in productivity also occurred in spinning and weaving wool and linen, although they were not as great as in cotton.

Finance

[edit]

The growth of Britain's industry stimulated a concomitant growth in its system of finance and credit. In the 18th century, services offered by banks increased. Clearing facilities, security investments, cheques and overdraft protections were introduced. Cheques had been invented in the 17th century in England, and banks settled payments by direct courier to the issuing bank. Around 1770, they began meeting in a central location, and by the 19th century a dedicated space was established, known as a bankers' clearing house. The London clearing house used a method where each bank paid cash to and then was paid cash by an inspector at the end of each day. The first overdraft facility was set up in 1728 by The Royal Bank of Scotland.

The end of the Napoleonic War and the subsequent rebound in trade led to an expansion in the bullion reserves held by the Bank of England, from a low of under 4 million pounds in 1821 to 14 million pounds by late 1824.

Older innovations became routine parts of financial life during the 19th century. The Bank of England first issued bank notes during the 17th century, but the notes were hand written and few in number. After 1725, they were partially printed, but cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to a named person. In 1844, parliament passed the Bank Charter Act tying these notes to gold reserves, effectively creating the institution of central banking and monetary policy. The notes became fully printed and widely available from 1855.[citation needed]

Growing international trade increased the number of banks, especially in London. These new "merchant banks" facilitated trade growth, profiting from England's emerging dominance in seaborne shipping. Two immigrant families, Rothschild and Baring, established merchant banking firms in London in the late 18th century and came to dominate world banking in the next century. The tremendous wealth amassed by these banking firms soon attracted much attention. The poet George Gordon Byron wrote in 1823: "Who makes politics run glibber all?/ The shade of Bonaparte's noble daring?/ Jew Rothschild and his fellow-Christian, Baring."

The operation of banks also shifted. At the beginning of the century, banking was still an elite preoccupation of a handful of very wealthy families. Within a few decades, however, a new sort of banking had emerged, owned by anonymous stockholders, run by professional managers, and the recipient of the deposits of a growing body of small middle-class savers. Although this breed of banks was newly prominent, it was not new – the Quaker family Barclays had been banking in this way since 1690.

Free trade and globalization

[edit]At the height of the First French Empire, Napoleon sought to introduce a "continental system" that would render Europe economically autonomous, thereby emasculating British trade and commerce. It involved such stratagems as the use of beet sugar in preference to the cane sugar that had to be imported from the tropics. Although this caused businessmen in England to agitate for peace, Britain persevered, in part because it was well into the Industrial Revolution. The war had the opposite effect – it stimulated the growth of certain industries, such as pig-iron production which increased from 68,000 tons in 1788 to 244,000 by 1806.[citation needed]

In 1817, David Ricardo, James Mill and Robert Torrens, in the famous theory of comparative advantage, argued that free trade would benefit the industrially weak as well as the strong. In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo advanced the doctrine still considered the most counterintuitive in economics:

- When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit.

By the mid 19th century, Britain was firmly wedded to the notion of free trade, and the first era of globalization began.[20] In the 1840s, the Corn Laws and the Navigation Acts were repealed, ushering in a new age of free trade. In line with the teachings of the classical political economists, led by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Britain embraced liberalism, encouraging competition and the development of a market economy.

Industrialization allowed cheap production of household items using economies of scale,[citation needed] while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. Nineteenth-century imperialism decisively shaped globalization in this period. After the First and Second Opium Wars and the completion of the British conquest of India, vast populations of these regions became ready consumers of European exports. During this period, areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific islands were incorporated into the world system. Meanwhile, the European conquest of new parts of the globe, notably sub-Saharan Africa, yielded valuable natural resources such as rubber, diamonds and coal and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies, and the United States.[35]

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914.

The global financial system was mainly tied to the gold standard during this period. The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow was Canada in 1853, Newfoundland in 1865, and the United States and Germany (de jure) in 1873. New technologies, such as the telegraph, the transatlantic cable, the Radiotelephone, the steamship, and the railway allowed goods and information to move around the world at an unprecedented degree.[36]

The eruption of civil war in the United States in 1861 and the blockade of its ports to international commerce meant that the main supply of cotton for the Lancashire looms was cut off. The textile industries shifted to reliance upon cotton from Africa and Asia during the course of the U.S. civil war, and this created pressure for an Anglo-French controlled canal through the Suez peninsula. The Suez canal opened in 1869, the same year in which the Central Pacific Railroad that spanned the North American continent was completed. Capitalism and the engine of profit were making the globe a smaller place.

20th century

[edit]Several major challenges to capitalism appeared in the early part of the 20th century. The Russian revolution in 1917 established the first state with a ruling communist party in the world; a decade later, the Great Depression triggered increasing criticism of the existing capitalist system. One response to this crisis was a turn to fascism, an ideology that advocated state capitalism.[37] Another response was to reject capitalism altogether in favour of communist or democratic socialist ideologies.

Keynesianism and free markets

[edit]

The economic recovery of the world's leading capitalist economies in the period following the end of the Great Depression and the Second World War—a period of unusually rapid growth by historical standards—eased discussion of capitalism's eventual decline or demise.[38] The state began to play an increasingly prominent role to moderate and regulate the capitalistic system throughout much of the world.

Keynesian economics became a widely accepted method of government regulation and countries such as the United Kingdom experimented with mixed economies in which the state owned and operated certain major industries.

The state also expanded in the US; in 1929, total government expenditures amounted to less than one-tenth of GNP; from the 1970s they amounted to around one-third.[21] Similar increases were seen in all industrialised capitalist economies, some of which, such as France, have reached even higher ratios of government expenditures to GNP than the United States.

A broad array of new analytical tools in the social sciences were developed to explain the social and economic trends of the period, including the concepts of post-industrial society and the welfare state.[20]

The long post-war boom ended in the 1970s, amid the economic crises experienced following the 1973 oil crisis.[39] The "stagflation" of the 1970s led many economic commentators and politicians to embrace market-oriented policy prescriptions inspired by the laissez-faire capitalism and classical liberalism of the nineteenth century, particularly under the influence of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. The theoretical alternative to Keynesianism was more compatible with laissez-faire and emphasised individual rights and absence of government intervention. Market-oriented solutions gained increasing support in the Western world, especially under the leadership of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called collectivist concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism".[40]

The three booming decades that followed the Second World War, according to political economist Clara E. Mattei, were an anomaly in the history of contemporary capitalism. She writes that austerity did not originate with the emergence of the neoliberal era starting in the 1970s, but "has been the mainstay of capitalism."[41]

Globalization

[edit]

Although overseas trade has been associated with the development of capitalism for over five hundred years, some thinkers argue that a number of trends associated with globalisation have acted to increase the mobility of people and capital since the last quarter of the twentieth century, combining to circumscribe the room to manoeuvre of states in choosing non-capitalist models of development. Today, these trends have bolstered the argument that capitalism should now be viewed as a truly world system (Burnham). However, other thinkers argue that globalisation, even in its quantitative degree, is no greater now than during earlier periods of capitalist trade.[42]

After the abandonment of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, and the strict state control of foreign exchange rates, the total value of transactions in foreign exchange was estimated to be at least twenty times greater than that of all foreign movements of goods and services (EB). The internationalisation of finance, which some see as beyond the reach of state control, combined with the growing ease with which large corporations have been able to relocate their operations to low-wage states, has posed the question of the 'eclipse' of state sovereignty, arising from the growing 'globalization' of capital.[43]

While economists generally agree about the size of global income inequality, there is a general disagreement about the recent direction of change of it.[44] In cases such as China, where income inequality is clearly growing[45] it is also evident that overall economic growth has rapidly increased with capitalist reforms.[46] Indur M. Goklany's book The Improving State of the World, published by the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, argues that economic growth since the Industrial Revolution has been very strong and that factors such as adequate nutrition, life expectancy, infant mortality, literacy, prevalence of child labor, education, and available free time have improved greatly.[47] Some scholars, including Stephen Hawking[48] and researchers for the International Monetary Fund,[49][50] contend that globalization and neoliberal economic policies are not ameliorating inequality and poverty but exacerbating it,[51][52][53] and are creating new forms of contemporary slavery.[54][55] Such policies are also expanding populations of the displaced, the unemployed and the imprisoned[56][57] along with accelerating the destruction of the environment[51] and species extinction.[58][59] In 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, in spite of global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so sharply that it threatens economic growth and could result in further political polarization.[60] Surging economic inequality following the economic crisis and the anger associated with it have resulted in a resurgence of socialist and nationalist ideas throughout the Western world, which has some economic elites from places including Silicon Valley, Davos and Harvard Business School concerned about the future of capitalism.[61]

According to the scholars Gary Gerstle and Fritz Bartel, with the end of the Cold War and the emergence of neoliberal financialized capitalism as the dominant system, capitalism has become a truly global order in a way not seen since 1914.[62][63] Economist Radhika Desai, while concurring that 1914 was the peak of the capitalist system, argues that the neoliberal reforms that were intended to restore capitalism to its primacy have instead bequeathed to the world increased inequalities, divided societies, economic crises and misery and a lack of meaningful politics, along with sluggish growth which demonstrates that, according to Desai, the system is "losing ground in terms of economic weight and world influence" with "the balance of international power . . . tilting markedly away from capitalism."[64] Gerstle argues that in the twilight of the neoliberal period "political disorder and dysfunction reign" and posits that the most important question for the United States and the world is what comes next.[62]

21st century

[edit]By the beginning of the twenty-first century, mixed economies with capitalist elements had become the pervasive economic systems worldwide. The collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1991 significantly reduced the influence of socialism as an alternative economic system. Leftist movements continue to be influential in some parts of the world, most notably Latin-American Bolivarianism, with some having ties to more traditional anti-capitalist movements, such as Bolivarian Venezuela's ties to Cuba.

In many emerging markets, the influence of banking and financial capital have come to increasingly shape national developmental strategies, leading some to argue we are in a new phase of financial capitalism.[65]

State intervention in global capital markets following the 2007–2008 financial crisis was perceived by some as signalling a crisis for free-market capitalism. Serious turmoil in the banking system and financial markets due in part to the subprime mortgage crisis reached a critical stage during September 2008, characterised by severely contracted liquidity in the global credit markets posed an existential threat to investment banks and other institutions.[66][67]

Future

[edit]According to Michio Kaku,[68] the transition to the information society involves abandoning some parts of capitalism, as the "capital" required to produce and process information becomes available to the masses and difficult to control, and is closely related to the controversial issues of intellectual property. Some[68] have further speculated that the development of mature nanotechnology, particularly of universal assemblers, may make capitalism obsolete, with capital ceasing to be an important factor in the economic life of humanity. Various thinkers have also explored what kind of economic system might replace capitalism, such as Bob Avakian, Jason Hickel, Paul Mason, Richard D. Wolff and contributors to the "Scientists' warning on affluence".[69]

Role of women

[edit]Women's historians have debated the impact of capitalism on the status of women.[70][71] Alice Clark argued that, when capitalism arrived in 17th-century England, it negatively impacted the status of women, who lost much of their economic importance. Clark argued that, in 16th-century England, women were engaged in many aspects of industry and agriculture. The home was a central unit of production, and women played a vital role in running farms and in some trades and landed estates. Their useful economic roles gave them a sort of equality with their husbands. However, Clark argued, as capitalism expanded in the 17th century, there was more and more division of labor, with the husband taking paid labor jobs outside the home, and the wife reduced to unpaid household work. Middle-class women were confined to an idle domestic existence, supervising servants; lower-class women were forced to take poorly paid jobs. Capitalism, therefore, had a negative effect on women.[72] By contrast, Ivy Pinchbeck argued that capitalism created the conditions for women's emancipation.[73] Tilly and Scott have emphasized the continuity and the status of women, finding three stages in European history. In the preindustrial era, production was mostly for home use, and women produced many household needs. The second stage was the "family wage economy" of early industrialization. During this stage, the entire family depended on the collective wages of its members, including husband, wife, and older children. The third, or modern, stage is the "family consumer economy", in which the family is the site of consumption, and women are employed in large numbers in retail and clerical jobs to support rising standards of consumption.[74]

See also

[edit]- 2007–2008 financial crisis

- Brenner debate

- Capitalism and Islam

- Capitalist mode of production

- Enclosure and British Agricultural Revolution

- Fernand Braudel

- History of capitalist theory

- History of globalization

- History of private equity and venture capital

- Primitive accumulation of capital

- Protestant work ethic

- Simple commodity production

References

[edit]- ^ Richard Biernacki, review of Ellen Meiksins Wood (1999), The Origin of Capitalism (Monthly Review Press, 1999), in Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Jul., 2000), pp. 638–39 JSTOR 2654574.

- ^ Ellen Meiksins Wood (2002), The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (London: Verso, 2002).

- ^ Hickel, Jason (2017). "3 – Where did poverty come from? A creation story". The divide : a brief guide to global inequality and its solutions. London: Penguin Random House. ISBN 9781785151125. OCLC 984907212.

- ^ Brenner, Robert, 1977, "The Origins of Capitalist Development: a Critique of Neo-Smithian Marxism", in New Left Review 104: 36–37, 46

- ^ Dobb, Maurice 1947 Studies in the Development of Capitalism. New York: International Publishers Co., Inc. 42–46, 48 ff.

- ^ James Fulcher, Capitalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004) 19

- ^

Degen, Robert A. (2011-12-31). The Triumph of Capitalism. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers (published 2011). p. 12. ISBN 9781412809856. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

By the early 1400s, power came to be shared in an arrangement giving representation to various segments of the social order, but the dichotomy between wage earners and capitalist merchants remained.

- ^ Ellen Meikisins Wood, The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View, 2nd edn (London: Verso, 2002), p. 99.

- ^ "Enclosure" is the modern spelling, while "inclosure" is an older spelling still used in the United Kingdom in legal documents and place names.

- ^ Thompson, E. P. (1991). The Making of the English Working Class. Penguin. p. 217.

- ^ A comparison of the English historical enclosures with the (much later) German 19th century Landflucht. Engels, Friedrich (1882). "Die Mark". Die Entwicklung des Sozialismus von der Utopie zur Wissenschaft. Hottingen (Zurich).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich. Werke (1973 reprint of 196t 1st ed.). Berlin: Karl Dietz. - ^ Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1786090034.

- ^ W. A. Armstrong

- ^ Chambers, J. D.; Mingay, G. E. (1982). The Agricultural Revolution 1750–1850 (Reprinted ed.). Batsford. p. 104.

- ^ Armstrong, W A (1981). The Influence of Demographic Factors on the Position of the Agricultural Labourer in England and Wales, c.1750–1914". in "Agricultural History Review.". Vol. 29. British Agricultural History Society. p. 79. Archived from the original on 2019-08-01. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ellen Meiksins Wood (2002), The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (London: Verso, 2002), pp. 73–94.

- ^ Warburton, David, Macroeconomics from the beginning: The General Theory, Ancient Markets, and the Rate of Interest. Paris: Recherches et Publications, 2003. p. 49

- ^ Trivellato, Francesca (2020). "Renaissance Florence and the Origins of Capitalism: A Business History Perspective". Business History Review. 94 (1): 229–251. doi:10.1017/S0007680520000033. ISSN 0007-6805.

- ^ Fredona, Robert; Reinert, Sophus A. (2020). "Italy and the Origins of Capitalism". Business History Review. 94 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1017/S0007680520000057. ISSN 0007-6805.

- ^ a b c d Burnham, Peter Capitalism, the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, 2003 Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica (2006)

- ^ John J. McCusker, Mercantilism and the Economic History of the Early Modern Atlantic World (Cambridge UP, 2001)

- ^ Now attributed to Sir Thomas Smith; quoted in Braudel (1979), p. 204.

- ^ David Onnekink; Gijs Rommelse (2011). Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 257. ISBN 9781409419143.

- ^ Quoted in Sir George Clark, The Seventeenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 24.

- ^ Scott, John; Marshall, Gordon (2005). "capitalism". Oxford Dictionary of Sociology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860986-5.

- ^ Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation. Beacon Press, Boston. 1944. p. 87

- ^ a b Jairus Banaji (2007), "Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism", Journal Historical Materialism 15#1 pp. 47–74, Brill Publishers.

- ^ Economic system :: Market systems. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006.

- ^ "chartered company". Archived from the original on 2009-01-09.

- ^ Ellen Meiksins Wood (2002), The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (London: Verso, 2002), pp. 142–46.

- ^ Inikori, Joseph E.. Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/709818

- ^ Harvey, Mark (4 October 2019). "Slavery, coerced labour, and the development of industrial capitalism in Britain". History Workshop. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Ayres, Robert (1989). Technological Transformations and Long Waves (PDF). International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. pp. 16–17. ISBN 3-7045-0092-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ^ "PBS.org". PBS.org. 1929-10-24. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- ^ Michael D. Bordo, Barry Eichengreen, Douglas A. Irwin. "Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hundred Years Ago?". NBER Working Paper No.7195. June 1999.

- ^ Reich, Wilhelm (1970). The Mass Psychology of Fascism. Macmillan. pp. 277–281. ISBN 978-0-374-20364-1.

- ^ Stanley Engerman; Seymour Drescher; Robert Paquette (2001). Slavery (Oxford Readers). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Barnes, Trevor J. (2004). Reading economic geography. Blackwell Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 0-631-23554-X.

- ^ Fulcher, James. Capitalism. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Mattei, Clara E. (2022). The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism. University of Chicago Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0226818399.

Austerity is not new, nor is it a product of the so-called Neoliberal Era that began in the 1970s. Outside, perhaps, of the less than three booming decades that followed World War II, austerity has been the mainstay of capitalism. It has been true throughout history that where capitalism exists, crisis follows. Where austerity has proven wildly effective is in insulating capitalist hierarchies from harm during these moments of would-be social change.

- ^ Doug Henwood is an economist who has argued that the heyday of globalisation was during the mid-nineteenth century. For example, he writes in What Is Globalization Anyway?:

Not only is the novelty of "globalization" exaggerated, so is its extent. Capital flows were freer, and foreign holdings by British investors far larger, 100 years ago than anything we see today. Images of multinational corporations shuttling raw materials and parts around the world, as if the whole globe were an assembly line, are grossly overblown, accounting for only about a tenth of U.S. trade.[1]

(See also Henwood, Doug (October 1, 2003). After the New Economy. New Press. ISBN 1-56584-770-9.)

- ^ For an assessment of this question, see Peter Evans, "The Eclipse of the State? Reflections on Stateness in an Era of Globalization", World Politics, 50, 1 (October 1997): 62–87.

- ^ Milanovic, Branko (2006-08-01). Global Income Inequality: What It Is And Why It Matters? (PDF) (Technical report). DESA Working Paper. Vol. 26. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Brooks, David (2004-11-27). "Good News about Poverty". Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ Fengbo Zhang: Speech at "Future China Global Forum 2010": China Rising with the Reform and Open Policy Archived 2013-10-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dahl, Robert (2000). On Democracy. Yale University: Yale Nota Bene. pp. 168. ISBN 0-300-07627-4.

- ^ This is the most dangerous time for our planet. Stephen Hawking via The Guardian. 1 December 2016.

- ^ Neoliberalism: Oversold? – IMF Finance & Development June 2016 • Volume 53 • Number 2

- ^ IMF: The last generation of economic policies may have been a complete failure. Business Insider. May 2016.

- ^ a b Jones, Campbell, Martin Parker and Rene Ten Bos, For Business Ethics. (Routledge, 2005) ISBN 0415311357, p. 101

- ^ Stephen Haymes, Maria Vidal de Haymes and Reuben Miller (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States, (London: Routledge, 2015) ISBN 0415673445, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Jason Hickel (February 13, 2019). An Open Letter to Steven Pinker (and Bill Gates). Jacobin. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Bales, Kevin (2012). Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520272910.

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj (2018). The Courage of Hopelessness: A Year of Acting Dangerously. Melville House. p. 29. ISBN 978-1612190037.

- ^ Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. (Harvard University Press, 2014) ISBN 0674599225

- ^ Loïc Wacquant. Prisons of Poverty Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. University of Minnesota Press (2009). p. 55 ISBN 0816639019.

- ^ Dawson, Ashley (2016). Extinction: A Radical History. OR Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-1944869014.

- ^ Harvey, David (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0199283273.

- ^ Dunsmuir, Lindsay (October 11, 2017). "IMF calls for fiscal policies that tackle rising inequality". Reuters. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg (April 20, 2019). "Capitalism in crisis: U.S. billionaires worry about the survival of the system that made them rich". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Gerstle, Gary (2022). The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–12, 293. ISBN 978-0197519646.

- ^ Bartel, Fritz (2022). The Triumph of Broken Promises: The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism. Harvard University Press. pp. 5–6, 19. ISBN 9780674976788.

- ^ Desai, Radhika (2022). Capitalism, Coronavirus and War: A Geopolitical Economy. Routledge. pp. 6–8, 179. doi:10.4324/9781003200000. ISBN 9781032059501. S2CID 254306409.

While the balance of class power remains heavily tilted in favour of capital in its homelands, the balance of international power is tilting markedly away from capitalism, driving all outside the charmed circle of the United States, Europe, Japan and the settler colonies bit by bit, with advances and reverses, steadily away from the major capitalist countries and probably, from capitalism. This process began with the Russian Revolution and, after the reverses of the 1990s, resumed in the new century as an alliance of countries seeking to assert their economic and security sovereignty—including Russia, Venezuela, Cuba and Iran—began forming with China as its economic centre. The pandemic and the war have accelerated these processes.

- ^ Marois, Thomas (2012) States, Banks and Crisis: Emerging Finance Capitalism in Mexico and Turkey. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ^ "President Bush Meets with Bicameral and Bipartisan Members of Congress to Discuss Economy", Whitehouse.gov, September 25, 2008.

- ^ "House votes down bail-out package". 29 September 2008 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ a b Kaku, Michio (1999). Visions: How Science Will Revolutionize the 21st Century and Beyond. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-288018-7

- ^ Wiedmann, Thomas; Lenzen, Manfred; Keyßer, Lorenz T.; Steinberger, Julia K. (2020). "Scientists' warning on affluence". Nature Communications. 11 (3107): 3107. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3107W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. PMC 7305220. PMID 32561753.

The second, more radical, group disagrees and argues that the needed socio-ecological transformation will necessarily entail a shift beyond capitalism and/or current centralised states. Although comprising considerable heterogeneity, it can be divided into eco-socialist approaches, viewing the democratic state as an important means to achieve the socio-ecological transformation and eco-anarchist approaches, aiming instead at participatory democracy without a state, thus minimising hierarchies. Many degrowth approaches combine elements of the two, but often see a stronger role for state action than eco-anarchists.

- ^ Eleanor Amico, ed. Reader's guide to women's studies (1998) pp. 102–04.

- ^ Janet Thomas, "Women and capitalism: oppression or emancipation? A review article". Comparative studies in society and history 30#3 (1988): 534–49. JSTOR 178999.

- ^ Alice Clark, Working life of women in the seventeenth century (1919).

- ^ Ivy Pinchbeck, Women Workers in the Industrial Revolution (1930).

- ^ Louise Tilly and Joan Wallach Scott, Women, work, and family (1987).

Further reading

[edit]- Appleby, Joyce. The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism (2011)

- Business History Review, Special issue on Italy and the Origins of Capitalism, Business History Review, Volume 94 - Issue 1 - Spring 2020.

- Braudel, Fernand (1979), "The Wheels of Commerce", Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century

- Cheta, Omar Youssef. "The economy by other means: The historiography of capitalism in the modern Middle East", History Compass (April 2018) 16#4 doi:10.1111/hic3.12444

- Comninel, George C. "English feudalism and the origins of capitalism" Journal of Peasant Studies, 27#4 (2000), pp. 1–53 doi:10.1080/03066150008438748

- Maurice Dobb and Paul Sweezy's famous debate on transition from feudalism to capitalism. Hilton, Rodney H. 1976. ed. The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism.

- blog on the Dobb-Sweezy debate Leftspot.com

- Duplessis, Robert S. Transitions to Capitalism in Early Modern Europe (1997).

- Friedman, Walter A. "Recent trends in business history research: Capitalism, democracy, and innovation". Enterprise & Society 18.4 (2017): 748–771.

- Giddens, Anthony. Capitalism and modern social theory: An analysis of the writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber (1971).

- Hilt, Eric. "Economic History, Historical Analysis, and the 'New History of Capitalism'". Journal of Economic History (June 2017) 77#2 pp 511–536. online

- Kocka, Jürgen. Capitalism: A Short History (2016) excerpt

- McCarraher, Eugene. The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity (2022) excerpt

- Marx, Karl (1867) Das Kapital

- Morton, Adam David. "The Age of Absolutism: capitalism, the modern states-system and international relations" Review of International Studies (2005), 31 : 495–517 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0260210505006601

- Neal, Larry, and Jeffrey G. Williamson, eds. The Cambridge History of Capitalism (2 Vol 2016)

- Olmstead, Alan L., and Paul W. Rhode. "Cotton, slavery, and the new history of capitalism". Explorations in Economic History 67 (2018): 1–17. online Archived 2021-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- O'Sullivan, Mary. "The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Capitalism". Enterprise & Society 19.4 (2018): 751–802. online

- Nolan, Peter (2009) Crossroads: The end of wild capitalism. Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0-462-09968-2

- Patriquin, Larry "The Agrarian Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England" Review of Radical Political Economics, Vol. 36, No. 2, 196–216 (2004) doi:10.1177/0486613404264190

- Perelman, Michael (2000) The Invention of Capitalism: Classical Political Economy and the Secret History of Primitive Accumulation. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2491-1, ISBN 978-0-8223-2491-1

- Prak, Maarten; Zanden, Jan Luiten van (2022). Pioneers of Capitalism: The Netherlands 1000–1800. Princeton University Press.

- Schuessler, Jennifer. "In History Departments, It's Up With Capitalism" April 6, 2013 The New York Times

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. Can capitalism survive? (1978)

- James Denham-Steuart [1767] An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy vol 1, vol2, vol 3

- Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (2002).

- Zmolek, Mike (2000). "The case for Agrarian capitalism: A response to albritton" Journal of Peasant Studies, Volume 27, Issue 4 July 2000, pp. 138–59

- Zmolek M. (2001) DEBATE – Further Thoughts on Agrarian Capitalism: A Reply to Albritton The Journal of Peasant Studies, Volume 29, Number 1, October 2001, pp. 129–54 (26)

- Debating Agrarian Capitalism: A Rejoinder to Albritton

- Research in Political Economy, Volume 22

- The Roots of Merchant Capitalism

- World Socialist Movement. "What Is Capitalism?" World Socialism. 13, August 2007.

- Thomas K. McCraw, "The Current Crisis and the Essence of Capitalism", The Montreal Review (August, 2011)

- Zofia Łapniewska, "History of Capitalism", Museum des Kapitalismus, Berlin 2014.