Deportations from East Prussia during World War I

In 1914–1915, the Russian Empire forcibly deported local inhabitants from Russian-occupied areas of East Prussia to more remote areas of the empire, particularly Siberia. The official rationale was to reduce espionage and other resistance behind the Russian front lines.[1] As many as 13,600 people, including children and the elderly, were deported.[2] Due to difficult living conditions, the mortality rates were high, and only 8,300 people returned home after the war.[2]

| Russian atrocities in East Prussia in World War I | |

|---|---|

| Part of War crimes in World War I | |

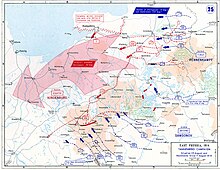

Map of military movements in East Prussia in 1914 | |

| Location | East Prussia, Germany |

| Date | 1914-1915 |

| Target | German civilians |

Attack type | Deportation, mass murder,[3] arson[4] |

| Deaths | At least c. 5,300 |

| Victims | 13,600 deported |

| Perpetrators | Imperial Russian Army |

The deportations had not received much attention from scholars, as they were overshadowed by the much larger refugee crisis in the Russian Empire[5] and the expulsion of Germans after World War II.[6]

Background

[edit]Military action began on the Eastern Front on 17 August 1914 with the Battle of Stallupönen during the Russian invasion of East Prussia.[7] As the German army was concentrated on the Western Front, Russians occupied about two-thirds of East Prussia[5] and stood just 40 kilometres (25 mi) away from Königsberg. It was the only German Empire territory, apart from Alsace-Lorraine on the Western Front, that saw direct military actions during the war.[6] The Russians were defeated in the Battle of Tannenberg and retreated, but counterattacked in October 1914. This time, they captured about one-fifth of East Prussia.[5] The front stabilized until February 1915 when the Russians were driven out during the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes.[6] These two waves of Russian attacks were accompanied by two mass population movements in different directions: locals evacuating deeper into Germany and deportations into Siberia. Contemporary estimates put the number of refugees into Germany at 870,000 in August and 300,000 in October.[6] For comparison, the 1910 German census recorded a total population of 2,064,175 in East Prussia.[8]

Russians deeply distrusted the German population. Even before battles began, MVD issued an order to treat every male citizen of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary between ages 18 and 45 as a civilian prisoner of war. Supposedly to prevent espionage, such people were deported out of European Russia.[9] Such policies resulted in the deportation of some 200,000 Germans from Volhynia and Bessarabia.[10] Generally, the internment of civilians of enemy nationality became a common practice among the warring states.[11]

Deportations

[edit]| District | Deportees 1915 reports |

Deportees Fritz Gause (1931) |

|---|---|---|

| Allenstein | 3,040 | 3,410 |

| Gumbinnen | 6,449 | 9,044 |

| Königsberg | 1,196 | 1,112 |

| Total | 10,685 | 13,566 |

In the occupied areas of East Prussia, Russians suspected civilians to be involved in resistance. The distrust was bolstered by cultural differences. For example, Germans owned and used bicycles that Russians associated with official or military business;[1] Germans were also not accustomed to carrying passports or other identity papers.[13] Local spies were used as scapegoats to justify military defeats.[5] Additionally, the removal of adult males reduced the number of potential new recruits when the German army returned.[12] The deportations started during the first Russian occupation, but were of smaller scale (at least 1,000 people)[6] and targeted primarily men of military age.[5] For example, out of 724 people deported from the Königsberg area only 10 were not adult males.[12] Deportations during the second occupation grew in number, and included many children, women, and the elderly.[5] In total, the deported people included about 4,000 women and 2,500 children.[12]

The people were herded on foot or transported using requisitioned wagons to train stations, mostly in Šiauliai but also in Vilnius, packed into cattle cars, and taken on a weeks-long train journey into interior of Russia.[9] The deportations were poorly organized and coordinated. Some Lutherans from the Šiauliai area were deported as well when they were mistaken for Germans.[9] The officials were confused whether to treat them as refugees, deportees, civilian internees, or prisoners of war.[2] Their condition was deplorable: many did not have basic necessities (such as money, food, warmer clothing), did not speak Russian, and did not have any papers, and the Russian government had no organized plans to provide food for the journey or housing at the destination.[14] No care was taken to deport families together and many were split up.[13] Due to cold and lack of food and medical care, many deportees died on the journey or soon after. For example, Prussian Lithuanian activist Martynas Jankus was deported at the end of 1914 together with his entire family to Bugulma.[5] In his memoirs, he recounted four deaths even before reaching the train. His 85-year-old father and 4-year-old son died at the destination by mid-January 1915.[5] In total, out of 350 deportees to Bugulma, 52 died. Felicija Bortkevičienė, who visited various deportees communities in 1916, estimated mortality rates of 15–20%.[15]

At the destination, living conditions and treatment of the deportees varied greatly. Some deportees were forced to work in mines or railway construction.[2] In other places, such as Astrakhan, the deportees had to first obtain work permits before they could find employment.[5] Yet in other places, such as Barnaul, the deportees were treated as prisoners and were guarded by armed soldiers.[15] Sometimes, the Russian administration provided a few kopeks per day to the deportees but amounts and conditions associated with these payments varied greatly.[5] The German government organized monthly stipends for deportees, but not everyone was able to receive it.[15] For example, according to Jankus, after May 1915, his deportee group received no assistance from either Russians or Germans for an entire year.[5]

In February 1915, Germany and Russia concluded an agreement for the mutual repatriation of civilian prisoners which provided that deportees, except for healthy males ages 17 to 45 that were fit for military duty, could return to their native country. However, many deportees lacked identity papers and the Russian authorities denied or delayed many passport applications.[5] In March 1917, after the February Revolution, the Russian Provisional Government revoked all extrajudicial punishments thus granting amnesty and freedom of movement to all deportees.[5] The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed in March 1918, provided a free-of-charge repatriation of civil prisoners, but the process was delayed due to the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War.[6] Generally, the deportees returned between 1919 and 1921.[16]

Atrocities

[edit]Upon the withdrawal of the German army, the Russian army “burned down every building” and began to shoot at and beat German civilians. Reports quickly surfaced of German civilians being tortured and murdered, villages and farms set on fire, and the arrest of officials as Tsarist troops poured into East Prussia’s southern and eastern borders. Just prior to the Battle of Tannenburg, the German deputy chancellor, Clemens Delbrück, reported in a telegraph that the Russians were “annihilating property and lives of population in the occupied areas with unheard-of brutality.”[17]

Relief efforts

[edit]Activists noticed the deportees and their deplorable conditions at the train stations, primarily in Vilnius, and organized help – provided food and clothing, exchanged German marks for Russian rubles, and gave them pre-addressed envelopes enabling them to inform others of their location.[14] At the destinations, the deportees received some help from various local committees. The German government provided aid via diplomats of neutral countries, i.e. the United States embassy until the American entry into World War I and then the Swedish embassy as well as the Danish consuls.[5] Together with POWs, the deportees received some help from the International Committee of the Red Cross[16] and other non-government organizations such as the Committee for Military and Civilian Prisoners in Tianjin (German: Hilfsaktion für Kriegs- und Zivilgefangene in Tientsin) which channeled relief funds from Germany and Austria-Hungary.[18] The Lithuanians established a relief society that specifically focused on the deportees and particularly on the Lithuanian-speaking Prussian Lithuanians.[14]

Lithuanian Care

[edit]At first, the Lithuanians wanted to join the Vilnius chapter of the All-Russian Society for the Care of Slavic Prisoners (Russian: Всероссийское общество попечительства о пленных славянах), but Polish activists voted them out, arguing that Lithuanians were not Slavic.[14] Therefore, on 2 February [O.S. 20 January] 1915, they established their own Lithuanian Care to Provide Assistance to Our Captive Lithuanian Brothers from Prussian Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvių globa mūsų broliams lietuviams belaisviams iš Prūsų Lietuvos šelpti).[19] The society was chaired by Felicija Bortkevičienė and included Mykolas Sleževičius, Jonas Vileišis, and others.[20] It was based in Vilnius but after the Great Retreat, moved to Saint Petersburg and then to Saratov where some deportees lived.[19] The society stopped its activities when its funds were nationalized after the October Revolution.[14]

It was difficult to obtain information on the deportees from Russian officials and the Lithuanian Care had to send its own representatives to investigate the situation, register the deportees, and organize help. It sent Steponas Kairys and Pranas Keinys to European Russia where they found 1,000 deportees in Saratov, 600 in Samara, 100 in Simbirsk, and a few others in Ufa, Orenburg.[14] Bortkevičienė toured Siberia for five months searching for deportees in Omsk, Tomsk, Irkutsk, Tobolsk, Altai Krai, Akmolinsk, Yeniseysk, and elsewhere.[9] She found the largest group of about 1,300 deportees spread out in the Buzulk district.[14] In total, the Lithuanian Care registered about 8,000 deportees[13] and maintained three shelters for 55 orphans, four shelters for 150 elderly people, and six primary schools for 150 students.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Buttar, Prit (2017). Germany Ascendant: The Eastern Front 1915. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4728-1355-8.

- ^ a b c d Kramer, Alan (2012). "Combatants and Noncombatants: Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes". In Horne, John (ed.). A Companion to World War I. John Wiley & Sons. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-119-96870-2.

- ^ Watson, Alexander (2014). ""Unheard-of Brutality": Russian Atrocities against Civilians in East Prussia, 1914–1915". The Journal of Modern History. 86 (4): 780–825. doi:10.1086/678919.

- ^ Watson, Alexander (2014). ""Unheard-of Brutality": Russian Atrocities against Civilians in East Prussia, 1914–1915". The Journal of Modern History. 86 (4): 780–825. doi:10.1086/678919.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Perrin, Charles (2016). "Eating bread with tears: Martynas Jankus and the deportation of East Prussian civilians to Russia during World War I". Journal of Baltic Studies. 3 (48): 1–10. doi:10.1080/01629778.2016.1178655. ISSN 1751-7877. S2CID 147932306.

- ^ a b c d e f Leiserowitz, Ruth (2017). "Population displacement in East Prussia during the First World War". In Gatrell, Peter; Zhvanko, Liubov (eds.). Europe on the Move: Refugees in the Era of the Great War. Manchester University Press. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-1-7849-9441-9.

- ^ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8500 Battles from Antiquity to the Twenty First Century. Vol. 3. Greenwood Press. p. 967. ISBN 978-0-313-33539-6.

- ^ Colby, Frank Moore; Churchill, Allen Leon, eds. (1912). New International Yearbook: A Compendium of the World's Progress for the Year 1911. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 293. OCLC 183333553.

- ^ a b c d Arbušauskaitė, Arūnė Liucija (2016-11-21). "Prūsijos lietuviai – Rusijos caro tremtiniai Didžiajame kare (1914-1918)" (in Lithuanian). Šilainės kraštas. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Pohl, J. Otto (2001). "The Deportation and Destruction of the German Minority in the USSR" (PDF). p. 5. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Stibbe, Matthew (2014-10-08). "Enemy Aliens and Internment". 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.15463/ie1418.10037. S2CID 55091759. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Watson, Alexander (December 2014). ""Unheard-of Brutality": Russian Atrocities against Civilians in East Prussia, 1914–1915" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 4 (86): 794, 796, 799. doi:10.1086/678919. ISSN 1537-5358. S2CID 143861167.

- ^ a b c Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija. Vol. II. Chicago: Dr. Kazio Griniaus Fondas. pp. 50–53. OCLC 3220435.

- ^ a b c d e f g Subačius, Liudas (2010). "Tremtinių iš Mažosios Lietuvos globa 1915–1918 m." (PDF). Kultūros barai (in Lithuanian). I: 84–86. ISSN 0134-3106.

- ^ a b c Šapoka, Gintautas (2015). "Prūsų lietuviai Sibire" (PDF). Terra Jatwezenorum. Istorijos paveldo metraštis (in Lithuanian). 7: 285, 297, 302, 307. ISSN 2080-7589.

- ^ a b Leiserowitz, Ruth (2017). "Population displacement in East Prussia during the First World War". In Gatrell, Peter; Zhvanko, Liubov (eds.). Europe on the Move: Refugees in the Era of the Great War. Manchester University Press. pp. 29, 39. ISBN 978-1-7849-9441-9.

- ^ Watson, Alexander (2014). ""Unheard-of Brutality": Russian Atrocities against Civilians in East Prussia, 1914–1915". The Journal of Modern History. 86 (4): 780–825. doi:10.1086/678919.

- ^ Rachamimov, Alon (2002). POWs and the Great War: Captivity on the Eastern Front. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-8597-3578-7.

- ^ a b Sperskienė, Rasa (2014-09-09). "Lietuvių globa šelpti broliams lietuviams iš Prūsų Lietuvos". Lietuvos visuomenė Pirmojo pasaulinio karo pradžioje: įvykiai, draugijos, asmenybės (in Lithuanian). Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Globa". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras. 2004-08-20. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Sperskienė, Rasa (2017-05-30). "Globa". Lietuviškos partijos ir organizacijos Rusijoje 1917–1918 metais (in Lithuanian). Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 6 January 2018.