Gravity

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

In physics, gravity (from Latin gravitas 'weight'[1]) is a fundamental interaction primarily observed as mutual attraction between all things that have mass. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong interaction, 1036 times weaker than the electromagnetic force and 1029 times weaker than the weak interaction. As a result, it has no significant influence at the level of subatomic particles.[2] However, gravity is the most significant interaction between objects at the macroscopic scale, and it determines the motion of planets, stars, galaxies, and even light.

On Earth, gravity gives weight to physical objects, and the Moon's gravity is responsible for sublunar tides in the oceans. The corresponding antipodal tide is caused by the inertia of the Earth and Moon orbiting one another. Gravity also has many important biological functions, helping to guide the growth of plants through the process of gravitropism and influencing the circulation of fluids in multicellular organisms.

The gravitational attraction between the original gaseous matter in the universe caused it to coalesce and form stars which eventually condensed into galaxies, so gravity is responsible for many of the large-scale structures in the universe. Gravity has an infinite range, although its effects become weaker as objects get farther away.

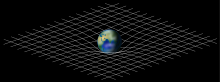

Gravity is most accurately described by the general theory of relativity, proposed by Albert Einstein in 1915, which describes gravity not as a force, but as the curvature of spacetime, caused by the uneven distribution of mass, and causing masses to move along geodesic lines. The most extreme example of this curvature of spacetime is a black hole, from which nothing—not even light—can escape once past the black hole's event horizon.[3] However, for most applications, gravity is well approximated by Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes gravity as a force causing any two bodies to be attracted toward each other, with magnitude proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Current models of particle physics imply that the earliest instance of gravity in the universe, possibly in the form of quantum gravity, supergravity or a gravitational singularity, along with ordinary space and time, developed during the Planck epoch (up to 10−43 seconds after the birth of the universe), possibly from a primeval state, such as a false vacuum, quantum vacuum or virtual particle, in a currently unknown manner.[4] Scientists are currently working to develop a theory of gravity consistent with quantum mechanics, a quantum gravity theory,[5] which would allow gravity to be united in a common mathematical framework (a theory of everything) with the other three fundamental interactions of physics.

Definitions

Gravitation, also known as gravitational attraction, is the mutual attraction between all masses in the universe. Gravity is the gravitational attraction at the surface of a planet or other celestial body;[6] gravity may also include, in addition to gravitation, the centrifugal force resulting from the planet's rotation .[7]

History

Ancient world

The nature and mechanism of gravity were explored by a wide range of ancient scholars. In Greece, Aristotle believed that objects fell towards the Earth because the Earth was the center of the Universe and attracted all of the mass in the Universe towards it. He also thought that the speed of a falling object should increase with its weight, a conclusion that was later shown to be false.[8] While Aristotle's view was widely accepted throughout Ancient Greece, there were other thinkers such as Plutarch who correctly predicted that the attraction of gravity was not unique to the Earth.[9]

Although he did not understand gravity as a force, the ancient Greek philosopher Archimedes discovered the center of gravity of a triangle.[10] He postulated that if two equal weights did not have the same center of gravity, the center of gravity of the two weights together would be in the middle of the line that joins their centers of gravity.[11] Two centuries later, the Roman engineer and architect Vitruvius contended in his De architectura that gravity is not dependent on a substance's weight but rather on its "nature".[12] In the 6th century CE, the Byzantine Alexandrian scholar John Philoponus proposed the theory of impetus, which modifies Aristotle's theory that "continuation of motion depends on continued action of a force" by incorporating a causative force that diminishes over time.[13]

In 628 CE, the Indian mathematician and astronomer Brahmagupta proposed the idea that gravity is an attractive force that draws objects to the Earth and used the term gurutvākarṣaṇ to describe it.[14]: 105 [15][16]

In the ancient Middle East, gravity was a topic of fierce debate. The Persian intellectual Al-Biruni believed that the force of gravity was not unique to the Earth, and he correctly assumed that other heavenly bodies should exert a gravitational attraction as well.[17] In contrast, Al-Khazini held the same position as Aristotle that all matter in the Universe is attracted to the center of the Earth.[18]

Scientific revolution

In the mid-16th century, various European scientists experimentally disproved the Aristotelian notion that heavier objects fall at a faster rate.[19] In particular, the Spanish Dominican priest Domingo de Soto wrote in 1551 that bodies in free fall uniformly accelerate.[19] De Soto may have been influenced by earlier experiments conducted by other Dominican priests in Italy, including those by Benedetto Varchi, Francesco Beato, Luca Ghini, and Giovan Bellaso which contradicted Aristotle's teachings on the fall of bodies.[19]

The mid-16th century Italian physicist Giambattista Benedetti published papers claiming that, due to specific gravity, objects made of the same material but with different masses would fall at the same speed.[20] With the 1586 Delft tower experiment, the Flemish physicist Simon Stevin observed that two cannonballs of differing sizes and weights fell at the same rate when dropped from a tower.[21] In the late 16th century, Galileo Galilei's careful measurements of balls rolling down inclines allowed him to firmly establish that gravitational acceleration is the same for all objects.[22] Galileo postulated that air resistance is the reason that objects with a low density and high surface area fall more slowly in an atmosphere.

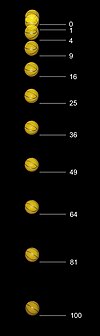

In 1604, Galileo correctly hypothesized that the distance of a falling object is proportional to the square of the time elapsed.[23] This was later confirmed by Italian scientists Jesuits Grimaldi and Riccioli between 1640 and 1650. They also calculated the magnitude of the Earth's gravity by measuring the oscillations of a pendulum.[24]

Newton's theory of gravitation

In 1657, Robert Hooke published his Micrographia, in which he hypothesized that the Moon must have its own gravity.[25] In 1666, he added two further principles: that all bodies move in straight lines until deflected by some force and that the attractive force is stronger for closer bodies. In a communication to the Royal Society in 1666, Hooke wrote[26]

I will explain a system of the world very different from any yet received. It is founded on the following positions. 1. That all the heavenly bodies have not only a gravitation of their parts to their own proper centre, but that they also mutually attract each other within their spheres of action. 2. That all bodies having a simple motion, will continue to move in a straight line, unless continually deflected from it by some extraneous force, causing them to describe a circle, an ellipse, or some other curve. 3. That this attraction is so much the greater as the bodies are nearer. As to the proportion in which those forces diminish by an increase of distance, I own I have not discovered it....

Hooke's 1674 Gresham lecture, An Attempt to prove the Annual Motion of the Earth, explained that gravitation applied to "all celestial bodies"[27]

In 1684, Newton sent a manuscript to Edmond Halley titled De motu corporum in gyrum ('On the motion of bodies in an orbit'), which provided a physical justification for Kepler's laws of planetary motion.[28] Halley was impressed by the manuscript and urged Newton to expand on it, and a few years later Newton published a groundbreaking book called Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy). In this book, Newton described gravitation as a universal force, and claimed that "the forces which keep the planets in their orbs must [be] reciprocally as the squares of their distances from the centers about which they revolve." This statement was later condensed into the following inverse-square law:

where F is the force, m1 and m2 are the masses of the objects interacting, r is the distance between the centers of the masses and G is the gravitational constant 6.674×10−11 m3⋅kg−1⋅s−2.[29]

Newton's Principia was well received by the scientific community, and his law of gravitation quickly spread across the European world.[30] More than a century later, in 1821, his theory of gravitation rose to even greater prominence when it was used to predict the existence of Neptune. In that year, the French astronomer Alexis Bouvard used this theory to create a table modeling the orbit of Uranus, which was shown to differ significantly from the planet's actual trajectory. In order to explain this discrepancy, many astronomers speculated that there might be a large object beyond the orbit of Uranus which was disrupting its orbit. In 1846, the astronomers John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier independently used Newton's law to predict Neptune's location in the night sky, and the planet was discovered there within a day.[31]

General relativity

| General relativity |

|---|

|

Eventually, astronomers noticed an eccentricity in the orbit of the planet Mercury which could not be explained by Newton's theory: the perihelion of the orbit was increasing by about 42.98 arcseconds per century. The most obvious explanation for this discrepancy was an as-yet-undiscovered celestial body, such as a planet orbiting the Sun even closer than Mercury, but all efforts to find such a body turned out to be fruitless. In 1915, Albert Einstein developed a theory of general relativity which was able to accurately model Mercury's orbit.[32]

In general relativity, the effects of gravitation are ascribed to spacetime curvature instead of a force. Einstein began to toy with this idea in the form of the equivalence principle, a discovery which he later described as "the happiest thought of my life."[33] In this theory, free fall is considered to be equivalent to inertial motion, meaning that free-falling inertial objects are accelerated relative to non-inertial observers on the ground.[34][35] In contrast to Newtonian physics, Einstein believed that it was possible for this acceleration to occur without any force being applied to the object.

Einstein proposed that spacetime is curved by matter, and that free-falling objects are moving along locally straight paths in curved spacetime. These straight paths are called geodesics. As in Newton's first law of motion, Einstein believed that a force applied to an object would cause it to deviate from a geodesic. For instance, people standing on the surface of the Earth are prevented from following a geodesic path because the mechanical resistance of the Earth exerts an upward force on them. This explains why moving along the geodesics in spacetime is considered inertial.

Einstein's description of gravity was quickly accepted by the majority of physicists, as it was able to explain a wide variety of previously baffling experimental results.[36] In the coming years, a wide range of experiments provided additional support for the idea of general relativity.[37]: p.1-9 [38][39][40][41] Today, Einstein's theory of relativity is used for all gravitational calculations where absolute precision is desired, although Newton's inverse-square law is accurate enough for virtually all ordinary calculations.[37]: p.79 [42]

Modern research

In modern physics, general relativity remains the framework for the understanding of gravity.[43] Physicists continue to work to find solutions to the Einstein field equations that form the basis of general relativity and continue to test the theory, finding excellent agreement in all cases.[44][45][37]: p.9

Einstein field equations

The Einstein field equations are a system of 10 partial differential equations which describe how matter affects the curvature of spacetime. The system is often expressed in the form where Gμν is the Einstein tensor, gμν is the metric tensor, Tμν is the stress–energy tensor, Λ is the cosmological constant, is the Newtonian constant of gravitation and is the speed of light.[46] The constant is referred to as the Einstein gravitational constant.[47]

A major area of research is the discovery of exact solutions to the Einstein field equations. Solving these equations amounts to calculating a precise value for the metric tensor (which defines the curvature and geometry of spacetime) under certain physical conditions. There is no formal definition for what constitutes such solutions, but most scientists agree that they should be expressable using elementary functions or linear differential equations.[48] Some of the most notable solutions of the equations include:

- The Schwarzschild solution, which describes spacetime surrounding a spherically symmetric non-rotating uncharged massive object. For compact enough objects, this solution generated a black hole with a central singularity.[49] At points far away from the central mass, the accelerations predicted by the Schwarzschild solution are practically identical to those predicted by Newton's theory of gravity.[50]

- The Reissner–Nordström solution, which analyzes a non-rotating spherically symmetric object with charge and was independently discovered by several different researchers between 1916 and 1921.[51] In some cases, this solution can predict the existence of black holes with double event horizons.[52]

- The Kerr solution, which generalizes the Schwarzchild solution to rotating massive objects. Because of the difficulty of factoring in the effects of rotation into the Einstein field equations, this solution was not discovered until 1963.[53]

- The Kerr–Newman solution for charged, rotating massive objects. This solution was derived in 1964, using the same technique of complex coordinate transformation that was used for the Kerr solution.[54]

- The cosmological Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker solution, discovered in 1922 by Alexander Friedmann and then confirmed in 1927 by Georges Lemaître. This solution was revolutionary for predicting the expansion of the Universe, which was confirmed seven years later after a series of measurements by Edwin Hubble.[55] It even showed that general relativity was incompatible with a static universe, and Einstein later conceded that he had been wrong to design his field equations to account for a Universe that was not expanding.[56]

Today, there remain many important situations in which the Einstein field equations have not been solved. Chief among these is the two-body problem, which concerns the geometry of spacetime around two mutually interacting massive objects, such as the Sun and the Earth, or the two stars in a binary star system. The situation gets even more complicated when considering the interactions of three or more massive bodies (the "n-body problem"), and some scientists suspect that the Einstein field equations will never be solved in this context.[57] However, it is still possible to construct an approximate solution to the field equations in the n-body problem by using the technique of post-Newtonian expansion.[58] In general, the extreme nonlinearity of the Einstein field equations makes it difficult to solve them in all but the most specific cases.[59]

Gravity and quantum mechanics

Despite its success in predicting the effects of gravity at large scales, general relativity is ultimately incompatible with quantum mechanics. This is because general relativity describes gravity as a smooth, continuous distortion of spacetime, while quantum mechanics holds that all forces arise from the exchange of discrete particles known as quanta. This contradiction is especially vexing to physicists because the other three fundamental forces (strong force, weak force and electromagnetism) were reconciled with a quantum framework decades ago.[60] As a result, modern researchers have begun to search for a theory that could unite both gravity and quantum mechanics under a more general framework.[61]

One path is to describe gravity in the framework of quantum field theory, which has been successful to accurately describe the other fundamental interactions. The electromagnetic force arises from an exchange of virtual photons, where the QFT description of gravity is that there is an exchange of virtual gravitons.[62][63] This description reproduces general relativity in the classical limit. However, this approach fails at short distances of the order of the Planck length,[64] where a more complete theory of quantum gravity (or a new approach to quantum mechanics) is required.

Tests of general relativity

Testing the predictions of general relativity has historically been difficult, because they are almost identical to the predictions of Newtonian gravity for small energies and masses.[65] Still, since its development, an ongoing series of experimental results have provided support for the theory:[65] In 1919, the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington was able to confirm the predicted gravitational lensing of light during that year's solar eclipse.[66][67] Eddington measured starlight deflections twice those predicted by Newtonian corpuscular theory, in accordance with the predictions of general relativity. Although Eddington's analysis was later disputed, this experiment made Einstein famous almost overnight and caused general relativity to become widely accepted in the scientific community.[68]

In 1959, American physicists Robert Pound and Glen Rebka performed an experiment in which they used gamma rays to confirm the prediction of gravitational time dilation. By sending the rays down a 74-foot tower and measuring their frequency at the bottom, the scientists confirmed that light is redshifted as it moves towards a source of gravity. The observed redshift also supported the idea that time runs more slowly in the presence of a gravitational field.[69] The time delay of light passing close to a massive object was first identified by Irwin I. Shapiro in 1964 in interplanetary spacecraft signals.[70]

In 1971, scientists discovered the first-ever black hole in the galaxy Cygnus. The black hole was detected because it was emitting bursts of x-rays as it consumed a smaller star, and it came to be known as Cygnus X-1.[71] This discovery confirmed yet another prediction of general relativity, because Einstein's equations implied that light could not escape from a sufficiently large and compact object.[72]

General relativity states that gravity acts on light and matter equally, meaning that a sufficiently massive object could warp light around it and create a gravitational lens. This phenomenon was first confirmed by observation in 1979 using the 2.1 meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, which saw two mirror images of the same quasar whose light had been bent around the galaxy YGKOW G1.[73][74]

Frame dragging, the idea that a rotating massive object should twist spacetime around it, was confirmed by Gravity Probe B results in 2011.[75][76] In 2015, the LIGO observatory detected faint gravitational waves, the existence of which had been predicted by general relativity. Scientists believe that the waves emanated from a black hole merger that occurred 1.5 billion light-years away.[77]

Specifics

Earth's gravity

Every planetary body (including the Earth) is surrounded by its own gravitational field, which can be conceptualized with Newtonian physics as exerting an attractive force on all objects. Assuming a spherically symmetrical planet, the strength of this field at any given point above the surface is proportional to the planetary body's mass and inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the center of the body.

The strength of the gravitational field is numerically equal to the acceleration of objects under its influence.[78] The rate of acceleration of falling objects near the Earth's surface varies very slightly depending on latitude, surface features such as mountains and ridges, and perhaps unusually high or low sub-surface densities.[79] For purposes of weights and measures, a standard gravity value is defined by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, under the International System of Units (SI).

The force of gravity experienced by objects on Earth's surface is the vector sum of two forces:[7] (a) The gravitational attraction in accordance with Newton's universal law of gravitation, and (b) the centrifugal force, which results from the choice of an earthbound, rotating frame of reference. The force of gravity is weakest at the equator because of the centrifugal force caused by the Earth's rotation and because points on the equator are furthest from the center of the Earth. The force of gravity varies with latitude and increases from about 9.780 m/s2 at the Equator to about 9.832 m/s2 at the poles.[80][81]

Gravitational radiation

General relativity predicts that energy can be transported out of a system through gravitational radiation. The first indirect evidence for gravitational radiation was through measurements of the Hulse–Taylor binary in 1973. This system consists of a pulsar and neutron star in orbit around one another. Its orbital period has decreased since its initial discovery due to a loss of energy, which is consistent for the amount of energy loss due to gravitational radiation. This research was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1993.[82]

The first direct evidence for gravitational radiation was measured on 14 September 2015 by the LIGO detectors. The gravitational waves emitted during the collision of two black holes 1.3 billion light years from Earth were measured.[83][84] This observation confirms the theoretical predictions of Einstein and others that such waves exist. It also opens the way for practical observation and understanding of the nature of gravity and events in the Universe including the Big Bang.[85] Neutron star and black hole formation also create detectable amounts of gravitational radiation.[86] This research was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2017.[87]

Speed of gravity

In December 2012, a research team in China announced that it had produced measurements of the phase lag of Earth tides during full and new moons which seem to prove that the speed of gravity is equal to the speed of light.[88] This means that if the Sun suddenly disappeared, the Earth would keep orbiting the vacant point normally for 8 minutes, which is the time light takes to travel that distance. The team's findings were released in Science Bulletin in February 2013.[89]

In October 2017, the LIGO and Virgo detectors received gravitational wave signals within 2 seconds of gamma ray satellites and optical telescopes seeing signals from the same direction. This confirmed that the speed of gravitational waves was the same as the speed of light.[90]

Anomalies and discrepancies

There are some observations that are not adequately accounted for, which may point to the need for better theories of gravity or perhaps be explained in other ways.

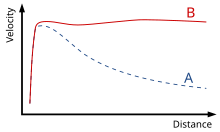

- Extra-fast stars: Stars in galaxies follow a distribution of velocities where stars on the outskirts are moving faster than they should according to the observed distributions of normal matter. Galaxies within galaxy clusters show a similar pattern. Dark matter, which would interact through gravitation but not electromagnetically, would account for the discrepancy. Various modifications to Newtonian dynamics have also been proposed.

- Accelerated expansion: The expansion of the universe seems to be speeding up.[91] Dark energy has been proposed to explain this.[92]

- Flyby anomaly: Various spacecraft have experienced greater acceleration than expected during gravity assist maneuvers.[93] The Pioneer anomaly has been shown to be explained by thermal recoil due to the distant sun radiation on one side of the space craft.[94][95]

Alternative theories

Historical alternative theories

- Aristotelian theory of gravity

- Le Sage's theory of gravitation (1784) also called LeSage gravity but originally proposed by Fatio and further elaborated by Georges-Louis Le Sage, based on a fluid-based explanation where a light gas fills the entire Universe.

- Ritz's theory of gravitation, Ann. Chem. Phys. 13, 145, (1908) pp. 267–271, Weber–Gauss electrodynamics applied to gravitation. Classical advancement of perihelia.

- Nordström's theory of gravitation (1912, 1913), an early competitor of general relativity.

- Kaluza–Klein theory (1921)

- Whitehead's theory of gravitation (1922), another early competitor of general relativity.

Modern alternative theories

- Brans–Dicke theory of gravity (1961)[96]

- Induced gravity (1967), a proposal by Andrei Sakharov according to which general relativity might arise from quantum field theories of matter

- String theory (late 1960s)

- ƒ(R) gravity (1970)

- Horndeski theory (1974)[97]

- Supergravity (1976)

- In the modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND) (1981), Mordehai Milgrom proposes a modification of Newton's second law of motion for small accelerations[98]

- The self-creation cosmology theory of gravity (1982) by G.A. Barber in which the Brans–Dicke theory is modified to allow mass creation

- Loop quantum gravity (1988) by Carlo Rovelli, Lee Smolin, and Abhay Ashtekar

- Nonsymmetric gravitational theory (NGT) (1994) by John Moffat

- Tensor–vector–scalar gravity (TeVeS) (2004), a relativistic modification of MOND by Jacob Bekenstein

- Chameleon theory (2004) by Justin Khoury and Amanda Weltman.

- Pressuron theory (2013) by Olivier Minazzoli and Aurélien Hees.

- Conformal gravity[99]

- Gravity as an entropic force, gravity arising as an emergent phenomenon from the thermodynamic concept of entropy.

- In the superfluid vacuum theory the gravity and curved spacetime arise as a collective excitation mode of non-relativistic background superfluid.

- Massive gravity, a theory where gravitons and gravitational waves have a non-zero mass

See also

- Anti-gravity – Idea of creating a place or object that is free from the force of gravity

- Artificial gravity – Use of circular rotational force to mimic gravity

- Equations for a falling body – Mathematical description of a body in free fall

- Escape velocity – Concept in celestial mechanics

- Atmospheric escape – Loss of planetary atmospheric gases to outer space

- Gauss's law for gravity – Restatement of Newton's law of universal gravitation

- Gravitational potential – Fundamental study of potential theory

- Gravitational biology – study of the effects gravity has on living organisms

- Newton's laws of motion – Laws in physics about force and motion

- Standard gravitational parameter – Concept in celestial mechanics

- Weightlessness – Zero apparent weight, microgravity

References

- ^ "dict.cc dictionary :: gravitas :: English-Latin translation". Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Krebs, Robert E. (1999). Scientific Development and Misconceptions Through the Ages: A Reference Guide (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-313-30226-8.

- ^ "HubbleSite: Black Holes: Gravity's Relentless Pull". hubblesite.org. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Staff. "Birth of the Universe". University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2016. – discusses "Planck time" and "Planck era" at the very beginning of the Universe

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (10 October 2022). "Black Holes May Hide a Mind-Bending Secret About Our Universe - Take gravity, add quantum mechanics, stir. What do you get? Just maybe, a holographic cosmos". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ McGraw-Hill Dict (1989)

- ^ a b Hofmann-Wellenhof, B.; Moritz, H. (2006). Physical Geodesy (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-33544-4.

§ 2.1: "The total force acting on a body at rest on the earth's surface is the resultant of gravitational force and the centrifugal force of the earth's rotation and is called gravity.

- ^ Cappi, Alberto. "The concept of gravity before Newton" (PDF). Culture and Cosmos. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Bakker, Frederik; Palmerino, Carla Rita (1 June 2020). "Motion to the Center or Motion to the Whole? Plutarch's Views on Gravity and Their Influence on Galileo". Isis. 111 (2): 217–238. doi:10.1086/709138. hdl:2066/219256. ISSN 0021-1753. S2CID 219925047. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Reviel Neitz; William Noel (13 October 2011). The Archimedes Codex: Revealing The Secrets of the World's Greatest Palimpsest. Hachette UK. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-78022-198-4. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ CJ Tuplin, Lewis Wolpert (2002). Science and Mathematics in Ancient Greek Culture. Hachette UK. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-19-815248-4. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Vitruvius, Marcus Pollio (1914). "7". In Alfred A. Howard (ed.). De Architectura libri decem [Ten Books on Architecture]. Herbert Langford Warren, Nelson Robinson (illus), Morris Hicky Morgan. Harvard University, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 215. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Philoponus' term for impetus is "ἑνέργεια ἀσώματος κινητική" ("incorporeal motive enérgeia"); see CAG XVII, Ioannis Philoponi in Aristotelis Physicorum Libros Quinque Posteriores Commentaria Archived 22 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Walter de Gruyter, 1888, p. 642: "λέγω δὴ ὅτι ἑνέργειά τις ἀσώματος κινητικὴ ἑνδίδοται ὑπὸ τοῦ ῥιπτοῦντος τῷ ῥιπτουμένῳ [I say that impetus (incorporeal motive energy) is transferred from the thrower to the thrown]."

- ^ Pickover, Clifford (16 April 2008). Archimedes to Hawking: Laws of Science and the Great Minds Behind Them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199792689. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Bose, Mainak Kumar (1988). Late classical India. A. Mukherjee & Co. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Sen, Amartya (2005). The Argumentative Indian. Allen Lane. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7139-9687-6.

- ^ Starr, S. Frederick (2015). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780691165851.

- ^ Rozhanskaya, Mariam; Levinova, I. S. (1996). "Statics". In Rushdī, Rāshid (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 2. Psychology Press. pp. 614–642. ISBN 9780415124119.

- ^ a b c Wallace, William A. (2018) [2004]. Domingo de Soto and the Early Galileo: Essays on Intellectual History. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 119, 121–22. ISBN 978-1-351-15959-3. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Drabkin, I. E. (1963). "Two Versions of G. B. Benedetti's Demonstratio Proportionum Motuum Localium". Isis. 54 (2): 259–262. doi:10.1086/349706. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 228543. S2CID 144883728.

- ^ Schilling, Govert (31 July 2017). Ripples in Spacetime: Einstein, Gravitational Waves, and the Future of Astronomy. Harvard University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780674971660. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Galileo (1638), Two New Sciences, First Day Salviati speaks: "If this were what Aristotle meant you would burden him with another error which would amount to a falsehood; because, since there is no such sheer height available on earth, it is clear that Aristotle could not have made the experiment; yet he wishes to give us the impression of his having performed it when he speaks of such an effect as one which we see."

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- ^ J.L. Heilbron, Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 180.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin (2017), p. 57.

- ^ Stewart, Dugald (1816). Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind. Vol. 2. Edinburgh; London: Constable & Co; Cadell & Davies. p. 434.

- ^ Hooke (1679), An Attempt to prove the Annual Motion of the Earth, page 2, 3.

- ^ Sagan, Carl & Druyan, Ann (1997). Comet. New York: Random House. pp. 52–58. ISBN 978-0-3078-0105-0. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "2022 CODATA Value: Newtonian constant of gravitation". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "The Reception of Newton's Principia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "This Month in Physics History". www.aps.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Nobil, Anna M. (March 1986). "The real value of Mercury's perihelion advance". Nature. 320 (6057): 39–41. Bibcode:1986Natur.320...39N. doi:10.1038/320039a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4325839.

- ^ Webb, Joh; Dougan, Darren (23 November 2015). "Without Einstein it would have taken decades longer to understand gravity". Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Gravity and Warped Spacetime". black-holes.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Dmitri Pogosyan. "Lecture 20: Black Holes – The Einstein Equivalence Principle". University of Alberta. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Brush, S. G. (1 January 1999). "Why was Relativity Accepted?". Physics in Perspective. 1 (2): 184–214. Bibcode:1999PhP.....1..184B. doi:10.1007/s000160050015. ISSN 1422-6944. S2CID 51825180. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Will, Clifford M. (2018). Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 9781107117440.

- ^ Lindley, David (12 July 2005). "The Weight of Light". Physics. 16. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Hafele-Keating Experiment". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "How the 1919 Solar Eclipse Made Einstein the World's Most Famous Scientist". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "At Long Last, Gravity Probe B Satellite Proves Einstein Right". www.science.org. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Hassani, Sadri (2010). From Atoms to Galaxies: A conceptual physics approach to scientific awareness. CRC Press. p. 131. ISBN 9781439808504.

- ^ Stephani, Hans (2003). Exact Solutions to Einstein's Field Equations. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-46136-8.

- ^ "Einstein's general relativity theory is questioned but still stands for now". Science News. Science Daily. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Lea, Robert (15 September 2022). "Einstein's greatest theory just passed its most rigorous test yet". Scientific American. Springer Nature America, Inc. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Einstein Field Equations (General Relativity)". University of Warwick. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "How to understand Einstein's equation for general relativity". Big Think. 15 September 2021. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ Ishak, Mustafa. "Exact Solutions to Einstein's Equations in Astrophysics" (PDF). University of Texas at Dallas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "The Schwarzchild Metric and Applications" (PDF). p. 36. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Ehlers, Jurgen (1997). "Examples of Newtonian limits of relativistic spacetimes". Classical Quantum Gravity. 14 (1A): 122–123. Bibcode:1997CQGra..14A.119E. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/14/1A/010. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-5AC5-F. S2CID 250804865. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "Surprise: the Big Bang isn't the beginning of the universe anymore". Big Think. 13 October 2021. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Norebo, Jonatan (16 March 2016). "The Reissner-Nordström metric" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Teukolsky, Saul (1 June 2015). "The Kerr metric" (PDF). Classical and Quantum Gravity. 32 (12): 124006. arXiv:1410.2130. Bibcode:2015CQGra..32l4006T. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/32/12/124006. S2CID 119219499. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Newman, E. T.; Couch, E.; Chinnapared, K.; Exton, A.; Prakash, A.; Torrence, R. (June 1965). "Metric of a Rotating, Charged Mass". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 6 (6): 918–919. Bibcode:1965JMP.....6..918N. doi:10.1063/1.1704351. ISSN 0022-2488. S2CID 122962090.

- ^ Pettini, M. "RELATIVISTIC COSMOLOGY" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ O’Raifeartaigh, Cormac; O’Keeffe, Michael (2017). "Einstein's 1917 Static Model of the Universe: A Centennial Review". The European Physical Journal H. 42 (3): 41. arXiv:1701.07261. Bibcode:2017EPJH...42..431O. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2017-80002-5. S2CID 119461771. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan. "This Is Why Scientists Will Never Exactly Solve General Relativity". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Spyrou, N. (1 May 1975). "The N-body problem in general relativity". The Astrophysical Journal. 197: 725–743. Bibcode:1975ApJ...197..725S. doi:10.1086/153562. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Sleator, Daniel (6 June 1996). "Hermeneutics of Classical General Relativity". Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Gravity Probe B – Special & General Relativity Questions and Answers". einstein.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Huggett, Nick; Matsubara, Keizo; Wüthrich, Christian (2020). Beyond Spacetime: The Foundations of Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781108655705.

- ^ Feynman, R.P.; Morinigo, F.B.; Wagner, W.G.; Hatfield, B. (1995). Feynman lectures on gravitation. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-62734-3.

- ^ Zee, A. (2003). Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01019-9.

- ^ Randall, Lisa (2005). Warped Passages: Unraveling the Universe's Hidden Dimensions. Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-053108-9.

- ^ a b "Testing General Relativity". NASA Blueshift. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Dyson, F.W.; Eddington, A.S.; Davidson, C.R. (1920). "A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun's Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919". Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A. 220 (571–581): 291–333. Bibcode:1920RSPTA.220..291D. doi:10.1098/rsta.1920.0009. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2019.. Quote, p. 332: "Thus the results of the expeditions to Sobral and Principe can leave little doubt that a deflection of light takes place in the neighbourhood of the sun and that it is of the amount demanded by Einstein's generalised theory of relativity, as attributable to the sun's gravitational field."

- ^ Weinberg, Steven (1972). Gravitation and cosmology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471925675.. Quote, p. 192: "About a dozen stars in all were studied, and yielded values 1.98 ± 0.11" and 1.61 ± 0.31", in substantial agreement with Einstein's prediction θ☉ = 1.75"."

- ^ Gilmore, Gerard; Tausch-Pebody, Gudrun (20 March 2022). "The 1919 eclipse results that verified general relativity and their later detractors: a story re-told". Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 76 (1): 155–180. arXiv:2010.13744. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2020.0040. S2CID 225075861.

- ^ "General Astronomy Addendum 10: Graviational Redshift and time dilation". homepage.physics.uiowa.edu. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Asada, Hideki (20 March 2008). "Gravitational time delay of light for various models of modified gravity". Physics Letters B. 661 (2–3): 78–81. arXiv:0710.0477. Bibcode:2008PhLB..661...78A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.02.006. S2CID 118365884. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "The Fate of the First Black Hole". www.science.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Black Holes Science Mission Directorate". webarchive.library.unt.edu. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Subal Kar (2022). Physics and Astrophysics: Glimpses of the Progress (illustrated ed.). CRC Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-000-55926-2. Extract of page 106

- ^ "Hubble, Hubble, Seeing Double!". NASA. 24 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "NASA's Gravity Probe B Confirms Two Einstein Space-Time Theories". Nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ ""Frame-Dragging" in Local Spacetime" (PDF). Stanford University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Gravitational Waves Detected 100 Years After Einstein's Prediction". Ligo Lab | Caltech. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Cantor, G.N.; Christie, J.R.R.; Hodge, M.J.S.; Olby, R.C. (2006). Companion to the History of Modern Science. Routledge. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-134-97751-2. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (15 December 2014). "The Potsdam Gravity Potato". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

- ^ Boynton, Richard (2001). "Precise Measurement of Mass" (PDF). Sawe Paper No. 3147. Arlington, Texas: S.A.W.E., Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Curious About Astronomy?". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1993". Nobel Foundation. 13 October 1993. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

for the discovery of a new type of pulsar, a discovery that has opened up new possibilities for the study of gravitation

- ^ Clark, Stuart (11 February 2016). "Gravitational waves: scientists announce 'we did it!' – live". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Witze (11 February 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. S2CID 182916902. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "WHAT ARE GRAVITATIONAL WAVES AND WHY DO THEY MATTER?". popsci.com. 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Abbott, B. P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration & Virgo Collaboration) (October 2017). "GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 119 (16): 161101. arXiv:1710.05832. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119p1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.161101. PMID 29099225. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Devlin, Hanna (3 October 2017). "Nobel prize in physics awarded for discovery of gravitational waves". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Chinese scientists find evidence for speed of gravity Archived 8 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, astrowatch.com, 12/28/12.

- ^ TANG, Ke Yun; HUA ChangCai; WEN Wu; CHI ShunLiang; YOU QingYu; YU Dan (February 2013). "Observational evidences for the speed of the gravity based on the Earth tide". Chinese Science Bulletin. 58 (4–5): 474–477. Bibcode:2013ChSBu..58..474T. doi:10.1007/s11434-012-5603-3.

- ^ "GW170817 Press Release". LIGO Lab – Caltech. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2011 : Adam G. Riess Facts". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "What is Dark Energy? Inside our accelerating, expanding Universe". science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Anderson, John D.; Campbell, James K.; Ekelund, John E.; Ellis, Jordan; Jordan, James F. (3 March 2008). "Anomalous Orbital-Energy Changes Observed during Spacecraft Flybys of Earth". Physical Review Letters. 100 (9): 091102. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100i1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.091102. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18352689.

- ^ Turyshev, Slava G.; Toth, Viktor T.; Kinsella, Gary; Lee, Siu-Chun; Lok, Shing M.; Ellis, Jordan (12 June 2012). "Support for the Thermal Origin of the Pioneer Anomaly". Physical Review Letters. 108 (24): 241101. arXiv:1204.2507. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108x1101T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.241101. PMID 23004253.

- ^ Iorio, Lorenzo (May 2015). "Gravitational anomalies in the solar system?". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 24 (6): 1530015–1530343. arXiv:1412.7673. Bibcode:2015IJMPD..2430015I. doi:10.1142/S0218271815300153. ISSN 0218-2718.

- ^ Brans, C.H. (March 2014). "Jordan–Brans–Dicke Theory". Scholarpedia. 9 (4): 31358. arXiv:gr-qc/0207039. Bibcode:2014SchpJ...931358B. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.31358.

- ^ Horndeski, G.W. (September 1974). "Second-Order Scalar–Tensor Field Equations in a Four-Dimensional Space". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 88 (10): 363–384. Bibcode:1974IJTP...10..363H. doi:10.1007/BF01807638. S2CID 122346086.

- ^ Milgrom, M. (June 2014). "The MOND paradigm of modified dynamics". Scholarpedia. 9 (6): 31410. Bibcode:2014SchpJ...931410M. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.31410.

- ^ Haugan, Mark P; Lämmerzahl, C (2011). "Einstein gravity from conformal gravity". arXiv:1105.5632 [hep-th].

Sources

- Gribbin, John; Gribbin, Mary (2017). Out of the shadow of a giant: Hooke, Halley and the birth of British science. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-822059-4. OCLC 966239842.

- McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Scientific and Technical Terms (4th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989, ISBN 0-07-045270-9

- Hooke, Robert (1679). Lectiones Cutlerianae, or A collection of lectures, physical, mechanical, geographical & astronomical : made before the Royal Society on several occasions at Gresham Colledge [i.e. College] : to which are added divers miscellaneous discourses.

Further reading

- I. Bernard Cohen (1999) [1687]. "A Guide to Newton's Principia". The Principia : mathematical principles of natural philosophy. By Newton, Isaac. Translated by I. Bernard Cohen. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520088160. OCLC 313895715.

- Halliday, David; Robert Resnick; Kenneth S. Krane (2001). Physics v. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-32057-9.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-534-40842-8.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (5th ed.). W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0809-4.

- Thorne, Kip S.; Misner, Charles W.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0.

- Panek, Richard (2 August 2019). "Everything you thought you knew about gravity is wrong". The Washington Post.