Portal:Stars

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: Harvard-Smithsonian/NASA

Mira, /ˈmaɪrə/, also known as Omicron Ceti (or ο Ceti / ο Cet), is a red giant star estimated 200-400 light years away in the constellation Cetus. Mira is a binary star, consisting of the red giant Mira A along with Mira B. Mira A is also an oscillating variable star and was the first non-supernova variable star discovered, with the possible exception of Algol. Apart from the unusual Eta Carinae, Mira is the brightest periodic variable in the sky that is not visible to the naked eye for part of its cycle. Its distance is uncertain; pre-Hipparcos estimates centered around 220 light-years, while Hipparcos data suggests a distance of 418 light-years, albeit with a margin of error of ~14%. Evidence that the variability of Mira was known in ancient China, Babylon or Greece is at best only circumstantial. In 1638 Johannes Holwarda determined a period of the star's reappearances, eleven months; he is often credited with the discovery of Mira's variability. Johannes Hevelius was observing it at the same time and named it "Mira" (meaning "wonderful" or "astonishing," in Latin) in 1662's Historiola Mirae Stellae, for it acted like no other known star. Ismail Bouillaud then estimated its period at 333 days, less than one day off the modern value of 332 days (and perfectly forgivable, as Mira is known to vary slightly in period, and may even be slowly changing over time). The star is estimated to be a 6 billion year old red giant.

Selected article - Photo credit: JAXA/NASA

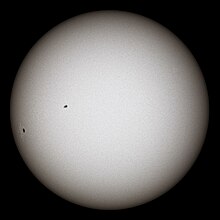

A solar flare is a large explosion in the Sun's atmosphere that can release as much as 6 × 1025 joules of energy. The term is also used to refer to similar phenomena in other stars, where the term stellar flare applies. Solar flares affect all layers of the solar atmosphere (photosphere, corona, and chromosphere), heating plasma to tens of millions of kelvins and accelerating electrons, protons, and heavier ions to near the speed of light. They produce radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum at all wavelengths, from radio waves to gamma rays. Most flares occur in active regions around sunspots, where intense magnetic fields penetrate the photosphere to link the corona to the solar interior. Flares are powered by the sudden (timescales of minutes to tens of minutes) release of magnetic energy stored in the corona. If a solar flare is exceptionally powerful, it can cause coronal mass ejections. X-rays and UV radiation emitted by solar flares can affect Earth's ionosphere and disrupt long-range radio communications. Direct radio emission at decimetric wavelengths may disturb operation of radars and other devices operating at these frequencies. Solar flares were first observed on the Sun by Richard Christopher Carrington and independently by Richard Hodgson in 1859 as localized visible brightenings of small areas within a sunspot group. Stellar flares have also been observed on a variety of other stars. The frequency of occurrence of solar flares varies, from several per day when the Sun is particularly "active" to less than one each week when the Sun is "quiet". Large flares are less frequent than smaller ones. Solar activity varies with an 11-year cycle (the solar cycle). At the peak of the cycle there are typically more sunspots on the Sun, and hence more solar flares. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA

This stellar swarm is Messier 80 (NGC 6093), one of the densest of the 147 known globular star clusters in the Milky Way galaxy, located about 28,000 light-years from Earth. Every star visible in this image is either more highly evolved than, or in a few rare cases more massive than, our own Sun. Especially obvious are the bright red giants, which are stars similar to the Sun in mass that are nearing the ends of their lives. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography - Photo credit: Eduard Ender

Tycho Brahe, born Tyge Ottesen Brahe (de Knudstrup) (14 December 1546 – 24 October 1601), was a Danish nobleman known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical and planetary observations. Coming from Scania, then part of Denmark, now part of modern-day Sweden, Tycho was well known in his lifetime as an astronomer and alchemist. His Danish name "Tyge Ottesen Brahe" is pronounced in Modern Standard Danish as [ˈtsʰyːə ˈʌtəsn̩ ˈpʁɑːə]. He adopted the Latinized name "Tycho Brahe" (usually /ˈtaɪkoʊ ˈbrɑː/ or /ˈbrɑːhiː/ in English) from Tycho (sometimes written Tÿcho) at around age fifteen, and he is now generally referred to as "Tycho", as was common in Scandinavia in his time, rather than by his surname "Brahe". (The incorrect form of his name, Tycho de Brahe, appeared only much later. Tycho Brahe was granted an estate on the island of Hven and the funding to build the Uraniborg, an early research institute, where he built large astronomical instruments and took many careful measurements. After disagreements with the new king in 1597, he was invited by the Bohemian king and Holy Roman emperor Rudolph II to Prague, where he became the official imperial astronomer. He built the new observatory at Benátky nad Jizerou. Here, from 1600 until his death in 1601, he was assisted by Johannes Kepler. Kepler later used Tycho's astronomical information to develop his own theories of astronomy.

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |