German Empire

German Empire Deutsches Reich (German) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871–1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: Gott mit uns (German)[2] Nobiscum Deus (Latin) ("God with us") | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Heil dir im Siegerkranz[3] ("Hail to Thee in the Victor's Crown") Die Wacht am Rhein (unofficial)[4][5][6] ("The Watch on the Rhine") | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

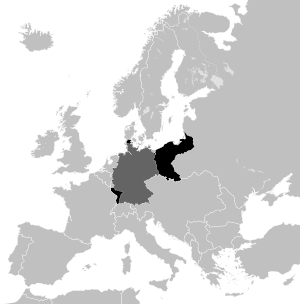

The German colonial empire in 1914 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Berlin 52°31′7″N 13°22′34″E / 52.51861°N 13.37611°E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | German | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | List

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion (1880) | Majority: 62.63% Protestant (United Protestant, Lutheran, Reformed) Minorities: 35.89% Roman Catholic 1.24% Judaism 0.17% other Christian 0.07% other | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | German | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy[7][8][9][10]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1871–1888 | Wilhelm I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1888 | Friedrich III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1888–1918 | Wilhelm II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1871–1890 | Otto von Bismarck | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1890–1894 | Leo von Caprivi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1894–1900 | C. zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1900–1909 | Bernhard von Bülow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1909–1917 | T. von Bethmann Hollweg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1917 | Georg Michaelis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1917–1918 | Georg von Hertling | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1918 | Max von Baden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Bicameral | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Upper house | Bundesrat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Lower house | Reichstag | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism • World War I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 January 1871 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 April 1871 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 November 1884 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 July 1914 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 November 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 November 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 November 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 August 1919 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 1,750,000 km2 (680,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1910[13] | 540,857.54 km2 (208,826.26 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Estimate | 70,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1871[14] | 41,058,792 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1900[14] | 56,367,178 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1910[14] | 64,925,993 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Until 1873: (1873–1914) German Papiermark (1914–1918) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Area and population not including colonial possessions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The German Empire (German: Deutsches Reich),[a][15][16][17][18] also referred to as Imperial Germany,[19] the Second Reich[b][20] or simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich[21][22] from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic.[23][24]

The empire was founded on 18 January 1871 at the Palace of Versailles, outside Paris, France, where the south German states, except for Austria and Liechtenstein, joined the North German Confederation and the new constitution came into force on 16 April, changing the name of the federal state to the German Empire and introducing the title of German Emperor for Wilhelm I, King of Prussia from the House of Hohenzollern.[25] Berlin remained its capital, and Otto von Bismarck, Minister President of Prussia, became chancellor, the head of government. As these events occurred, the Prussian-led North German Confederation and its southern German allies, such as Baden, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Hesse, were still engaged in the Franco-Prussian War. The German Empire consisted of 25 states, each with its own nobility, four constituent kingdoms, six grand duchies, five duchies (six before 1876), seven principalities, three free Hanseatic cities, and one imperial territory. While Prussia was one of four kingdoms in the realm, it contained about two-thirds of the Empire's population and territory, and Prussian dominance was also constitutionally established, since the King of Prussia was also the German Emperor (Deutscher Kaiser).

After 1850, the states of Germany had rapidly become industrialized, with particular strengths in coal, iron (and later steel), chemicals, and railways. In 1871, Germany had a population of 41 million people; by 1913, this had increased to 68 million. A heavily rural collection of states in 1815, the now united Germany became predominantly urban.[26] The success of German industrialization manifested itself in two ways in the early 20th century; German factories were often larger and more modern than many of their British and French counterparts, but the preindustrial sector was more backward.[27] The success of the German Empire in the natural sciences, especially in physics and chemistry, was such that one-third of all Nobel Prizes went to German inventors and researchers. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became an industrial, technological, and scientific power in Europe, and by 1913, Germany was the largest economy in continental Europe and the third-largest in the world.[28] Germany also became a great power, building the longest railway network of Europe, the world's strongest army,[29] and a fast-growing industrial base.[30] Starting very small in 1871, in a decade, the navy became second only to Britain's Royal Navy.

From 1871 to 1890, Otto von Bismarck's tenure as the first and to this day longest-serving chancellor was marked by relative liberalism at its start, but in time grew more conservative. Broad reforms, the anti-Catholic Kulturkampf and systematic repression of Polish people marked his period in the office. Despite his hatred of liberalism and socialism – he called liberals and socialists "enemies of the Reich" – social programs introduced by Bismarck included old-age pensions, accident insurance, medical care and unemployment insurance, all aspects of the modern European welfare state.

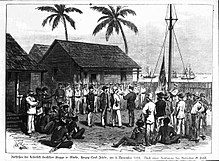

Late in Bismarck's chancellorship and in spite of his earlier personal opposition, Germany became involved in colonialism. Claiming much of the leftover territory that was not yet conquered by Europeans in the Scramble for Africa, it managed to build the third-largest colonial empire at the time, after the British and the French ones.[31] As a colonial state, it sometimes clashed with the interests of other European powers, especially the British Empire. During its colonial expansion, the German Empire committed the Herero and Nama genocide.[32]

After the resignation of Otto von Bismarck in 1890, and Wilhelm II's refusal to recall him to office, the empire embarked on Weltpolitik ("world politics") – a bellicose new course that ultimately contributed to the outbreak of World War I. Bismarck's successors were incapable of maintaining their predecessor's complex, shifting, and overlapping alliances which had kept Germany from being diplomatically isolated. This period was marked by increased oppression of Polish people and various factors influencing the Emperor's decisions, which were often perceived as contradictory or unpredictable by the public. In 1879, the German Empire consolidated the Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary, followed by the Triple Alliance with Italy in 1882. It also retained strong diplomatic ties to the Ottoman Empire. When the great crisis of 1914 arrived, Italy left the alliance and the Ottoman Empire formally allied with Germany.

In the First World War, German plans to capture Paris quickly in the autumn of 1914 failed, and the war on the Western Front became a stalemate. The Allied naval blockade caused severe shortages of food and supplements. However, Imperial Germany had success on the Eastern Front; it occupied a large amount of territory to its east following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 contributed to bringing the United States into the war. In October 1918, after the failed Spring Offensive, the German armies were in retreat, allies Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire had collapsed, and Bulgaria had surrendered. The empire collapsed in the November 1918 Revolution with the abdication of Wilhelm II, which left the post-war federal republic to govern a devastated populace. The Treaty of Versailles imposed post-war reparation costs of 132 billion gold marks (around US$269 billion or €240 billion in 2019, or roughly US$32 billion in 1921),[33] as well as limiting the army to 100,000 men and disallowing conscription, armored vehicles, submarines, aircraft, and more than six battleships.[34] The consequential economic devastation, later exacerbated by the Great Depression, as well as humiliation and outrage experienced by the German population are considered leading factors in the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism.[35]

History

Background

The German Confederation had been created by an act of the Congress of Vienna on 8 June 1815 as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, after being alluded to in Article 6 of the 1814 Treaty of Paris.[36]

The liberal Revolutions of 1848 were crushed after the relations between the educated, well-off middle-class liberals and the urban artisans broke down; Otto von Bismarck's pragmatic Realpolitik, which appealed to peasants as well as the aristocracy, took its place.[37] Bismarck sought to extend Hohenzollern hegemony throughout the German states; to do so meant unification of the German states and the exclusion of Prussia's main German rival, Austria, from the subsequent German Empire. He envisioned a conservative, Prussian-dominated Germany. The Second Schleswig War against Denmark in 1864, the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, and the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–1871 sparked a growing pan-German ideal and contributed to the formation of the German state.

The German Confederation ended as a result of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 between the constituent Confederation entities of the Austrian Empire and its allies on one side and Prussia and its allies on the other. The war resulted in the partial replacement of the Confederation in 1867 by a North German Confederation, comprising the 22 states north of the river Main. The patriotic fervor generated by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 overwhelmed the remaining opposition to a unified Germany (aside from Austria) in the four states south of the Main, and during November 1870, they joined the North German Confederation by treaty.[38]

Foundation

On 10 December 1870, the North German Confederation Reichstag renamed the Confederation the "German Empire" and gave the title of German Emperor to William I, the King of Prussia, as Bundespräsidium of the Confederation.[39] The new constitution (Constitution of the German Confederation) and the title Emperor came into effect on 1 January 1871. During the siege of Paris on 18 January 1871, William was proclaimed Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[40]

The second German Constitution, adopted by the Reichstag on 14 April 1871 and proclaimed by the Emperor on 16 April,[40] was substantially based upon Bismarck's North German Constitution. The political system remained the same. The empire had a parliament called the Reichstag, which was elected by universal male suffrage. However, the original constituencies drawn in 1871 were never redrawn to reflect the growth of urban areas. As a result, by the time of the great expansion of German cities in the 1890s and 1900s, rural areas were grossly over-represented.

The legislation also required the consent of the Bundesrat, the federal council of deputies from the 27 states. Executive power was vested in the emperor, or Kaiser, who was assisted by a chancellor responsible only to him. The emperor was given extensive powers by the constitution. He alone appointed and dismissed the chancellor (so in practice, the emperor ruled the empire through the chancellor), was supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and final arbiter of all foreign affairs, and could also disband the Reichstag to call for new elections. Officially, the chancellor was a one-man cabinet and was responsible for the conduct of all state affairs; in practice, the State Secretaries (top bureaucratic officials in charge of such fields as finance, war, foreign affairs, etc.) functioned much like ministers in other monarchies. The Reichstag had the power to pass, amend, or reject bills and to initiate legislation. However, as mentioned above, in practice, the real power was vested in the emperor, who exercised it through his chancellor.

Although nominally a federal empire and league of equals, in practice, the empire was dominated by the largest and most powerful state, Prussia. It stretched across the northern two-thirds of the new Reich and contained three-fifths of the country's population. The imperial crown was hereditary in the ruling house of Prussia, the House of Hohenzollern. With the exception of 1872–1873 and 1892–1894, the chancellor was always simultaneously the prime minister of Prussia. With 17 out of 58 votes in the Bundesrat, Berlin needed only a few votes from the smaller states to exercise effective control.

The other states retained their own governments but had only limited aspects of sovereignty. For example, both postage stamps and currency were issued for the empire as a whole. Coins through one mark were also minted in the name of the empire, while higher-valued pieces were issued by the states. However, these larger gold and silver issues were virtually commemorative coins and had limited circulation.

While the states issued their own decorations and some had their own armies, the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. Those of the larger states, such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony, were coordinated along Prussian principles and would, in wartime, be controlled by the federal government.

The evolution of the German Empire is somewhat in line with parallel developments in Italy, which became a united nation-state a decade earlier. Some key elements of the German Empire's authoritarian political structure were also the basis for conservative modernization in Imperial Japan under Emperor Meiji and the preservation of an authoritarian political structure under the tsars in the Russian Empire.

One factor in the social anatomy of these governments was the retention of a very substantial share in political power by the landed elite, the Junkers, resulting from the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the peasants in combination with urban areas.

Although authoritarian in many respects, the empire had some democratic features. Besides universal manhood suffrage, it permitted the development of political parties. Bismarck intended to create a constitutional façade that would mask the continuation of authoritarian policies. However, in the process, he created a system with a serious flaw. There was a significant disparity between the Prussian and German electoral systems. Prussia used a three-class voting system which weighted votes based on the amount of taxes paid,[41] all but assuring a conservative majority. The king and (with two exceptions) the prime minister of Prussia were also the emperor and chancellor of the empire – meaning that the same rulers had to seek majorities from legislatures elected from completely different franchises. Universal suffrage was significantly diluted by gross over-representation of rural areas from the 1890s onward. By the turn of the century, the urban-rural population balance was completely reversed from 1871; more than two-thirds of the empire's people lived in cities and towns.

Bismarck era

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

Bismarck's domestic policies played an important role in forging the authoritarian political culture of the Kaiserreich. Less preoccupied with continental power politics following unification in 1871, Germany's semi-parliamentary government carried out a relatively smooth economic and political revolution from above that pushed them along the way towards becoming the world's leading industrial power of the time.

Bismarck's "revolutionary conservatism" was a conservative state-building strategy designed to make ordinary Germans—not just the Junker elite—more loyal to the throne and empire. According to Kees van Kersbergen and Barbara Vis, his strategy was:

granting social rights to enhance the integration of a hierarchical society, to forge a bond between workers and the state so as to strengthen the latter, to maintain traditional relations of authority between social and status groups, and to provide a countervailing power against the modernist forces of liberalism and socialism.[42]

Bismarck created the modern welfare state in Germany in the 1880s and enacted universal male suffrage in 1871.[43] He became a great hero to German conservatives, who erected many monuments to his memory and tried to emulate his policies.[44]

Foreign policy

Bismarck's post-1871 foreign policy was conservative and sought to preserve the balance of power in Europe. British historian Eric Hobsbawm concludes that he "remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, [devoting] himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers".[45] This was a departure from his adventurous foreign policy for Prussia, where he favored strength and expansion, punctuating this by saying, "The great questions of the age are not settled by speeches and majority votes – this was the error of 1848–49 – but by iron and blood."[46]

Bismarck's chief concern was that France would plot revenge after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. As the French lacked the strength to defeat Germany by themselves, they sought an alliance with Russia, or perhaps even the newly reformed empire of Austria-Hungary, which would envelope Germany completely. Bismarck wanted to prevent this at all costs and maintain friendly relations with the Austrians and the Russians, signing the Dual Alliance (1879) with Austria-Hungary in 1879. The Dual Aliance was a defensive alliance that was established against Russia, and by association France, in the event alliance did not work out with the state. However, an alliance with Russia would come not long after the signing of the Dual Alliance with Austria, the Dreikaiserbund (League of Three Emperors), in 1881. During this period, individuals within the German military were advocating a preemptive strike against Russia, but Bismarck knew that such ideas were foolhardy. He once wrote that "the most brilliant victories would not avail against the Russian nation, because of its climate, its desert, and its frugality, and having but one frontier to defend", and because it would leave Germany with another bitter, resentful neighbor. Despite this, another alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy would be signed in 1882, preying on the fears of the German and Austro-Hungarian militaries of the untrustworthiness of Russia itself. This alliance, named the Triple Alliance (1882), would exist up until 1915, when Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. Despite Germany, and especially Austria's, lack of faith in the Russian alliance, the Reinsurance Treaty would be first signed in 1887, and renewed up until 1890, when the Bismarckian system collapsed upon Bismarck's resignation.

Meanwhile, the chancellor remained wary of any foreign policy developments that looked even remotely warlike. In 1886, he moved to stop an attempted sale of horses to France because they might be used for cavalry and also ordered an investigation into large Russian purchases of medicine from a German chemical works. Bismarck stubbornly refused to listen to Georg Herbert Münster, ambassador to France, who reported back that the French were not seeking a revanchist war and were desperate for peace at all costs.

Bismarck and most of his contemporaries were conservative-minded and focused their foreign policy attention on Germany's neighboring states. In 1914, 60% of German foreign investment was in Europe, as opposed to just 5% of British investment. Most of the money went to developing nations such as Russia that lacked the capital or technical knowledge to industrialize on their own. The construction of the Berlin–Baghdad railway, financed by German banks, was designed to eventually connect Germany with the Ottoman Empire and the Persian Gulf, but it also collided with British and Russian geopolitical interests. Conflict over the Baghdad Railway was resolved in June 1914.

Many consider Bismarck's foreign policy as a coherent system and partly responsible for the preservation of Europe's stability.[47] It was also marked by the need to balance circumspect defensiveness and the desire to be free from the constraints of its position as a major European power.[47] Bismarck's successors did not pursue his foreign policy legacy. For instance, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who dismissed the chancellor in 1890, let the treaty with Russia lapse in favor of Germany's alliance with Austria, which finally led to a stronger coalition-building between Russia and France.[48]

Colonies

Germans had dreamed of colonial imperialism since 1848.[49] Although Bismarck had little interest in acquiring overseas possessions, most Germans were enthusiastic, and by 1884 he had acquired German New Guinea.[50] By the 1890s, German colonial expansion in Asia and the Pacific (Jiaozhou Bay and Tianjin in China, the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, Samoa) led to frictions with the UK, Russia, Japan, and the US. The largest colonial enterprises were in Africa,[51] where the Herero Wars in what is now Namibia in 1906–1907 resulted in the Herero and Nama genocide.[52]

Economy

By 1900, Germany became the largest economy in continental Europe and the third-largest in the world behind the United States and the British Empire, which were also its main economic rivals. Throughout its existence, it experienced economic growth and modernization led by heavy industry. In 1871, it had a largely rural population of 41 million, while by 1913, this had increased to a predominantly urban population of 68 million.[53]

Industrial power

For 30 years, Germany struggled against Britain to be Europe's leading industrial power. Representative of Germany's industry was the steel giant Krupp, whose first factory was built in Essen. By 1902, the factory alone became "A great city with its own streets, its own police force, fire department and traffic laws. There are 150 kilometers of rail, 60 different factory buildings, 8,500 machine tools, seven electrical stations, 140 kilometers of underground cable, and 46 overhead."[54]

Under Bismarck, Germany was a world innovator in building the welfare state. German workers enjoyed health, accident and maternity benefits, canteens, changing rooms, and a national pension scheme.[55]

Industrialisation progressed dynamically in Germany, and German manufacturers began to capture domestic markets from British imports, and also to compete with British industry abroad, particularly in the U.S. The German textile and metal industries had by 1870 surpassed those of Britain in organisation and technical efficiency and superseded British manufacturers in the domestic market. Germany became the dominant economic power on the continent and was the second-largest exporting nation after Britain.[56]

Technological progress during German industrialisation occurred in four waves: the railway wave (1877–1886), the dye wave (1887–1896), the chemical wave (1897–1902), and the wave of electrical engineering (1903–1918).[57] Since Germany industrialised later than Britain, it was able to model its factories after those of Britain, thus making more efficient use of its capital and avoiding legacy methods in its leap to the envelope of technology. Germany invested more heavily than the British in research, especially in chemistry, ICE engines and electricity. Germany's dominance in physics and chemistry was such that one-third of all Nobel Prizes went to German inventors and researchers. The German cartel system (known as Konzerne), being significantly concentrated, was able to make more efficient use of capital. Germany was not weighted down with an expensive worldwide empire that needed defense. Following Germany's annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871, it absorbed parts of what had been France's industrial base.[58]

Germany overtook British steel production in 1893 and pig iron production in 1903. The German steel and pig iron production continued its rapid expansion: Between 1911 and 1913, the German steel and pig iron output reached one quarter of total global production.[59]

German factories were larger and more modern than their British and French counterparts.[27] By 1913, the German electricity production was higher than the combined electricity production of Britain, France, Italy and Sweden.[60]

By 1900, the German chemical industry dominated the world market for synthetic dyes.[61] The three major firms BASF,[62] Bayer and Hoechst produced several hundred different dyes, along with the five smaller firms. Imperial Germany built up the world's largest chemical industry, the production of German chemical industry was 60% higher than that of the United States.[60] In 1913, these eight firms produced almost 90% of the world supply of dyestuffs and sold about 80% of their production abroad. The three major firms had also integrated upstream into the production of essential raw materials and they began to expand into other areas of chemistry such as pharmaceuticals, photographic film, agricultural chemicals and electrochemicals. Top-level decision-making was in the hands of professional salaried managers; leading Chandler to call the German dye companies "the world's first truly managerial industrial enterprises".[63] There were many spinoffs from research—such as the pharmaceutical industry, which emerged from chemical research.[64]

By the start of World War I (1914–1918), German industry switched to war production. The heaviest demands were on coal and steel for artillery and shell production, and on chemicals for the synthesis of materials that were subject to import restrictions and for chemical weapons and war supplies.

Railways

Lacking a technological base at first, the Germans imported their engineering and hardware from Britain but quickly learned the skills needed to operate and expand the railways. In many cities, the new railway shops were the centers of technological awareness and training, so that by 1850, Germany was self-sufficient in meeting the demands of railroad construction, and the railways were a major impetus for the growth of the new steel industry. German unification in 1870 stimulated consolidation, nationalisation into state-owned companies, and further rapid growth. Unlike the situation in France, the goal was support of industrialisation, and so heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen. By 1880, Germany had 9,400 locomotives pulling 43,000 passengers and 30,000 tons of freight, and forged ahead of France.[65] The total length of German railroad tracks expanded from 21,000 km (13,000 mi) in 1871 to 63,000 km (39,000 mi) by 1913, establishing the largest rail network in the world after the United States.[66] The German rail network was followed by Austria-Hungary (43,280 km; 26,890 mi), France (40,770 km; 25,330 mi), the United Kingdom (32,623 km; 20,271 mi), Italy (18,873 km; 11,727 mi) and Spain (15,088 km; 9,375 mi).[67]

Consolidation

The creation of the Empire under Prussian leadership was a victory for the concept of Kleindeutschland (Smaller Germany) over the Großdeutschland concept. This meant that Austria-Hungary, a multi-ethnic Empire with a considerable German-speaking population, would remain outside of the German nation state. Bismarck's policy was to pursue a solution diplomatically.[citation needed] The effective alliance between Germany and Austria played a major role in Germany's decision to enter World War I in 1914.[citation needed]

Bismarck announced there would be no more territorial additions to Germany in Europe, and his diplomacy after 1871 was focused on stabilizing the European system and preventing any wars. He succeeded, and only after his departure from office in 1890 did the diplomatic tensions start rising again.[68]

Social issues

After achieving formal unification in 1871, Bismarck devoted much of his attention to the cause of national unity. He opposed Catholic civil rights and emancipation, especially the influence of the Vatican under Pope Pius IX, and working-class radicalism, represented by the emerging Social Democratic Party.

Kulturkampf

Prussia in 1871 included 16,000,000 Protestants, both Reformed and Lutheran, and 8,000,000 Catholics. Most people were generally segregated into their own religious worlds, living in rural districts or city neighbourhoods that were overwhelmingly of the same religion, and sending their children to separate public schools where their religion was taught. There was little interaction or intermarriage. On the whole, the Protestants had a higher social status, and the Catholics were more likely to be peasant farmers or unskilled or semiskilled industrial workers. In 1870, the Catholics formed their own political party, the Centre Party, which generally supported unification and most of Bismarck's policies. However, Bismarck distrusted parliamentary democracy in general and opposition parties in particular, especially when the Centre Party showed signs of gaining support among dissident elements such as the Polish Catholics in Silesia. A powerful intellectual force of the time was anti-Catholicism, led by the liberal intellectuals who formed a vital part of Bismarck's coalition. They saw the Catholic Church as a powerful force of reaction and anti-modernity, especially after the proclamation of papal infallibility in 1870, and the tightening control of the Vatican over the local bishops.[69]

The Kulturkampf launched by Bismarck 1871–1880 affected Prussia; although there were similar movements in Baden and Hesse, the rest of Germany was not affected. According to the new imperial constitution, the states were in charge of religious and educational affairs; they funded the Protestant and Catholic schools. In July 1871 Bismarck abolished the Catholic section of the Prussian Ministry of ecclesiastical and educational affairs, depriving Catholics of their voice at the highest level. The system of strict government supervision of schools was applied only in Catholic areas; the Protestant schools were left alone.[70]

Much more serious were the May laws of 1873. One made the appointment of any priest dependent on his attendance at a German university, as opposed to the seminaries that the Catholics typically used. Furthermore, all candidates for the ministry had to pass an examination in German culture before a state board which weeded out intransigent Catholics. Another provision gave the government a veto power over most church activities. A second law abolished the jurisdiction of the Vatican over the Catholic Church in Prussia; its authority was transferred to a government body controlled by Protestants.[71]

Nearly all German bishops, clergy, and laymen rejected the legality of the new laws, and were defiant in the face of heavier and heavier penalties and imprisonments imposed by Bismarck's government. By 1876, all the Prussian bishops were imprisoned or in exile, and a third of the Catholic parishes were without a priest. In the face of systematic defiance, the Bismarck government increased the penalties and its attacks, and were challenged in 1875 when a papal encyclical declared the whole ecclesiastical legislation of Prussia was invalid, and threatened to excommunicate any Catholic who obeyed. There was no violence, but the Catholics mobilized their support, set up numerous civic organizations, raised money to pay fines, and rallied behind their church and the Centre Party. The "Old Catholic Church", which rejected the First Vatican Council, attracted only a few thousand members. Bismarck, a devout pietistic Protestant, realized his Kulturkampf was backfiring when secular and socialist elements used the opportunity to attack all religion. In the long run, the most significant result was the mobilization of the Catholic voters, and their insistence on protecting their religious identity. In the elections of 1874, the Centre party doubled its popular vote, and became the second-largest party in the national parliament—and remained a powerful force for the next 60 years, so that after Bismarck it became difficult to form a government without their support.[72][73]

Social reform

Bismarck built on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that began as early as in the 1840s. In the 1880s he introduced old-age pensions, accident insurance, medical care and unemployment insurance that formed the basis of the modern European welfare state. He came to realize that this sort of policy was very appealing, since it bound workers to the state, and also fit in very well with his authoritarian nature. The social security systems installed by Bismarck (health care in 1883, accident insurance in 1884, invalidity and old-age insurance in 1889) at the time were the largest in the world and, to a degree, still exist in Germany today.

Bismarck's paternalistic programs won the support of German industry because its goals were to win the support of the working classes for the Empire and reduce the outflow of immigrants to America, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist.[55][74] Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers by his high tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.[75]

Antisemitism

As it was throughout Europe at the time, antisemitism was endemic in Germany during the period. Before Napoleon's decrees ended the ghettos in Confederation of the Rhine, it had been religiously motivated, but by the 19th century, it was a factor in German nationalism. In the popular mind, Jews became a symbol of capitalism and wealth. On the other hand, the constitution and legal system protected the rights of Jews as German citizens. Antisemitic parties were formed but soon collapsed.[76] But after the Treaty of Versailles, and Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany, antisemitism in Germany would increase.[77]

Germanisation

One of the effects of the unification policies was the gradually increasing tendency to eliminate the use of non-German languages in public life, schools and academic settings with the intent of pressuring the non-German population to abandon their national identity in what was called "Germanisation". These policies often had the reverse effect of stimulating resistance, usually in the form of homeschooling and tighter unity in the minority groups, especially the Poles.[78]

The Germanisation policies were targeted particularly against the significant Polish minority of the empire, gained by Prussia in the partitions of Poland. Poles were treated as an ethnic minority even where they made up the majority, as in the Province of Posen, where a series of anti-Polish measures was enforced.[79] Numerous anti-Polish laws had no great effect especially in the province of Posen where the German-speaking population dropped from 42.8% in 1871 to 38.1% in 1905, despite all efforts.[80]

Law

Bismarck's efforts also initiated the levelling of the enormous differences between the German states, which had been independent in their evolution for centuries, especially with legislation. The completely different legal histories and judicial systems posed enormous complications, especially for national trade. While a common trade code had already been introduced by the Confederation in 1861 (which was adapted for the Empire and, with great modifications, is still in effect today), there was little similarity in laws otherwise.

In 1871, a common criminal code was introduced; in 1877, common court procedures were established in the court system by the courts constitution act, code of civil procedure (Zivilprozessordnung) and code of criminal procedure (Strafprozessordnung [de]). In 1873 the constitution was amended to allow the Empire to replace the various and greatly differing Civil Codes of the states (If they existed at all; for example, parts of Germany formerly occupied by Napoleon's France had adopted the French Civil Code, while in Prussia the Allgemeines Preußisches Landrecht of 1794 was still in effect). In 1881, a first commission was established to produce a common Civil Code for all of the Empire, an enormous effort that would produce the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB), possibly one of the most impressive legal works in the world; it was eventually put into effect on 1 January 1900. All of these codifications are, albeit with many amendments, still in effect today.

-

Different legal systems in Germany prior to 1900

-

Fields of law in the German Empire

Year of the three emperors

On 9 March 1888, Wilhelm I died shortly before his 91st birthday, leaving his son Frederick as the new emperor. Frederick was a liberal and an admirer of the British constitution,[81] while his links to Britain strengthened further with his marriage to Princess Victoria, eldest child of Queen Victoria. With his ascent to the throne, many hoped that Frederick's reign would lead to a liberalization of the Reich and an increase of parliament's influence on the political process. The dismissal of Robert von Puttkamer, the highly conservative Prussian interior minister, on 8 June was a sign of the expected direction and a blow to Bismarck's administration.

By the time of his accession, however, Frederick had developed incurable laryngeal cancer, which had been diagnosed in 1887. He died on the 99th day of his rule, on 15 June 1888. His son Wilhelm became emperor.

Wilhelmine era

Bismarck's resignation

Wilhelm II wanted to reassert his ruling prerogatives at a time when other monarchs in Europe were being transformed into constitutional figureheads. This decision led the ambitious Kaiser into conflict with Bismarck. The old chancellor had hoped to guide Wilhelm as he had guided his grandfather, but the emperor wanted to be the master in his own house and had many sycophants telling him that Frederick the Great would not have been great with a Bismarck at his side.[82] A key difference between Wilhelm II and Bismarck was their approaches to handling political crises, especially in 1889, when German coal miners went on strike in Upper Silesia. Bismarck demanded that the German Army be sent in to crush the strike, but Wilhelm II rejected this authoritarian measure, responding "I do not wish to stain my reign with the blood of my subjects."[83] Instead of condoning repression, Wilhelm had the government negotiate with a delegation from the coal miners, which brought the strike to an end without violence.[82] The fractious relationship ended in March 1890, after Wilhelm II and Bismarck quarrelled, and the chancellor resigned days later.[82]

With Bismarck's departure, Wilhelm II became the dominant ruler of Germany. Unlike his grandfather, Wilhelm I, who had been largely content to leave government affairs to the chancellor, Wilhelm II wanted to be fully informed and actively involved in running Germany, not an ornamental figurehead, although most Germans found his claims of divine right to rule amusing.[84] Wilhelm allowed politician Walther Rathenau to tutor him in European economics and industrial and financial realities in Europe.[84]

As Hull (2004) notes, Bismarckian foreign policy "was too sedate for the reckless Kaiser".[85] Wilhelm became internationally notorious for his aggressive stance on foreign policy and his strategic blunders (such as the Tangier Crisis), which pushed the German Empire into growing political isolation and eventually helped to cause World War I.

Domestic affairs

Under Wilhelm II, Germany no longer had long-ruling strong chancellors like Bismarck. The new chancellors had difficulty in performing their roles, especially the additional role as Prime Minister of Prussia assigned to them in the German Constitution. The reforms of Chancellor Leo von Caprivi, which liberalized trade and so reduced unemployment, were supported by the Kaiser and most Germans except for Prussian landowners, who feared loss of land and power and launched several campaigns against the reforms.[86]

While Prussian aristocrats challenged the demands of a united German state, in the 1890s several organizations were set up to challenge the authoritarian conservative Prussian militarism which was being imposed on the country. Educators opposed to the German state-run schools, which emphasized military education, set up their own independent liberal schools, which encouraged individuality and freedom.[87] However nearly all the schools in Imperial Germany had a very high standard and kept abreast with modern developments in knowledge.[88]

Artists began experimental art in opposition to Kaiser Wilhelm's support for traditional art, to which Wilhelm responded "art which transgresses the laws and limits laid down by me can no longer be called art".[89] It was largely thanks to Wilhelm's influence that most printed material in Germany used blackletter instead of the Roman type used in the rest of Western Europe. At the same time, a new generation of cultural creators emerged.[90]

From the 1890s onwards, the most effective opposition to the monarchy came from the newly formed Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), whose radicals advocated Marxism. The threat of the SPD to the German monarchy and industrialists caused the state both to crack down on the party's supporters and to implement its own programme of social reform to soothe discontent. Germany's large industries provided significant social welfare programmes and good care to their employees, as long as they were not identified as socialists or trade-union members. The larger industrial firms provided pensions, sickness benefits and even housing to their employees.[87]

Having learned from the failure of Bismarck's Kulturkampf, Wilhelm II maintained good relations with the Roman Catholic Church and concentrated on opposing socialism.[91] This policy failed when the Social Democrats won a third of the votes in the 1912 elections to the Reichstag, and became the largest political party in Germany. The government remained in the hands of a succession of conservative coalitions supported by right-wing liberals or Catholic clerics and heavily dependent on the Kaiser's favour. The rising militarism under Wilhelm II caused many Germans to emigrate to the U.S. and the British colonies to escape mandatory military service.

During World War I, the Kaiser increasingly devolved his powers to the leaders of the German High Command, particularly future German president, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff. Hindenburg took over the role of commander–in–chief from the Kaiser, while Ludendorff became de facto general chief of staff. By 1916, Germany was effectively a military dictatorship run by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, with the Kaiser reduced to a mere figurehead.[92]

Foreign affairs

Colonialism

Wilhelm II wanted Germany to have her "place in the sun", like Britain, which he constantly wished to emulate or rival.[93] With German traders and merchants already active worldwide, he encouraged colonial efforts in Africa and the Pacific ("new imperialism"), causing the German Empire to vie with other European powers for remaining "unclaimed" territories. With the encouragement or at least the acquiescence of Britain, which at this stage saw Germany as a counterweight to her old rival France, Germany acquired German Southwest Africa (modern Namibia), German Kamerun (modern Cameroon), Togoland (modern Togo) and German East Africa (modern Rwanda, Burundi, and the mainland part of current Tanzania). Islands were gained in the Pacific through purchase and treaties and also a 99-year lease for the territory of Jiaozhou in northeast China. But of these German colonies only Togoland and German Samoa (after 1908) became self-sufficient and profitable; all the others required subsidies from the Berlin treasury for building infrastructure, school systems, hospitals and other institutions.

Bismarck had originally dismissed the agitation for colonies with contempt; he favoured a Eurocentric foreign policy, as the treaty arrangements made during his tenure in office show. As a latecomer to colonization, Germany repeatedly came into conflict with the established colonial powers and also with the United States, which opposed German attempts at colonial expansion in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. Native insurrections in German territories received prominent coverage in other countries, especially in Britain; the established powers had dealt with such uprisings decades earlier, often brutally, and had secured firm control of their colonies by then. The Boxer Rising in China, which the Chinese government eventually sponsored, began in the Shandong province, in part because Germany, as colonizer at Jiaozhou, was an untested power and had only been active there for two years. Seven western nations, including the United States, and Japan mounted a joint relief force to rescue westerners caught up in the rebellion. During the departure ceremonies for the German contingent, Wilhelm II urged them to behave like the Hun invaders of continental Europe – an unfortunate remark that would later be resurrected by British propagandists to paint Germans as barbarians during World War I and World War II[according to whom?]. On two occasions, a French-German conflict over the fate of Morocco seemed inevitable.

Upon acquiring Southwest Africa, German settlers were encouraged to cultivate land held by the Herero and Nama. Herero and Nama tribal lands were used for a variety of exploitative goals (much as the British did before in Rhodesia), including farming, ranching, and mining for minerals and diamonds. In 1904, the Herero and the Nama revolted against the colonists in Southwest Africa, killing farm families, their laborers and servants. In response to the attacks, troops were dispatched to quell the uprising which then resulted in the Herero and Nama Genocide. In total, some 65,000 Herero (80% of the total Herero population), and 10,000 Nama (50% of the total Nama population) perished. The commander of the punitive expedition, General Lothar von Trotha, was eventually relieved and reprimanded for his usurpation of orders and the cruelties he inflicted. These occurrences were sometimes referred to as "the first genocide of the 20th century" and officially condemned by the United Nations in 1985. In 2004 a formal apology by a government minister of the Federal Republic of Germany followed.

Middle East

Bismarck and Wilhelm II after him sought closer economic ties with the Ottoman Empire. Under Wilhelm II, with the financial backing of the Deutsche Bank, the Baghdad Railway was begun in 1900, although by 1914 it was still 500 km (310 mi) short of its destination in Baghdad.[94] In an interview with Wilhelm in 1899, Cecil Rhodes had tried "to convince the Kaiser that the future of the German empire abroad lay in the Middle East" and not in Africa; with a grand Middle-Eastern empire, Germany could afford to allow Britain the unhindered completion of the Cape-to-Cairo railway that Rhodes favoured.[95] Britain initially supported the Baghdad Railway; but by 1911 British statesmen came to fear it might be extended to Basra on the Persian Gulf, threatening Britain's naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean. Accordingly, they asked to have construction halted, to which Germany and the Ottoman Empire acquiesced.

South America

In South America, Germany's primary interest was in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay and viewed the countries of northern South America – Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela – as a buffer to protect its interest from the growing influence of the United States.[96] Policymakers in Germany analysed the possibility of establishing bases in Margarita Island and showed interest in the Galápagos Islands but soon abandoned any such designs given that far-flung bases in northern South America would be very vulnerable.[97][96] Germany attempted to promote Chile, a country that was heavily influenced by Germany,[98] into a regional counterweight to the United States.[96] Germany and Britain managed through Chile to have Ecuador deny the United States a naval base in the Galápagos Islands.[96]

Claims that German communities in South America acted as extensions of the German Empire were ubiquituous by 1900 but it has never been proved that these communities acted in such way to any significant degree.[99] German political, cultural and scientific influence was particularly intense in Chile in the decades before World War I, and the prestige of Germany and German things in Chile remained high after the war but did not recover to its pre-war levels.[98][99]

Pre-war Europe

Berlin was deeply suspicious of a supposed conspiracy of its enemies: that year-by-year in the early 20th century it was systematically encircled by enemies.[100] There was a growing fear that the supposed enemy coalition of Russia, France and Britain was getting stronger militarily every year, especially Russia. The longer Berlin waited the less likely it would prevail in a war.[101] According to American historian Gordon A. Craig, it was after the set-back in Morocco in 1905 that the fear of encirclement began to be a potent factor in German politics."[102] Few outside observers agreed with the notion of Germany as a victim of deliberate encirclement.[103][104] English historian G. M. Trevelyan expressed the British viewpoint:

The encirclement, such as it was, was of Germany's own making. She had encircled herself by alienating France over Alsace-Lorraine, Russia by her support of Austria-Hungary's anti—Slav policy in the Balkans, England by building her rival fleet. She had created with Austria-Hungary a military bloc in the heart of Europe so powerful and yet so restless that her neighbors on each side had no choice but either to become her vassals or to stand together for protection....They used their central position to create fear in all sides, in order to gain their diplomatic ends. And then they complained that on all sides they had been encircled.[105]

Wilhelm II, under pressure from his new advisors after Bismarck left, committed a fatal error when he decided to allow the "Reinsurance Treaty" that Bismarck had negotiated with Tsarist Russia to lapse. It allowed Russia to make a new alliance with France. Germany was left with no firm ally but Austria-Hungary, and her support for action in annexing Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 further soured relations with Russia. Berlin missed the opportunity to secure an alliance with Britain in the 1890s when it was involved in colonial rivalries with France, and he alienated British statesmen further by openly supporting the Boers in the South African War and building a navy to rival Britain's. By 1911, Wilhelm had completely picked apart the careful power balance established by Bismarck and Britain turned to France in the Entente Cordiale. Germany's only other ally besides Austria was the Kingdom of Italy, but it remained an ally only pro forma. When war came, Italy saw more benefit in an alliance with Britain, France, and Russia, which, in the secret Treaty of London in 1915 promised it the frontier districts of Austria and also colonial concessions. Germany did acquire a second ally in 1914 when the Ottoman Empire entered the war on its side, but in the long run, supporting the Ottoman war effort only drained away German resources from the main fronts.[106]

World War I

Origins

Following the assassination of the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip, the Kaiser offered Emperor Franz Joseph full support for Austro-Hungarian plans to invade the Kingdom of Serbia, which Austria-Hungary blamed for the assassination. This unconditional support for Austria-Hungary was called a "blank cheque" by historians, including German Fritz Fischer. Subsequent interpretation – for example at the Versailles Peace Conference – was that this "blank cheque" licensed Austro-Hungarian aggression regardless of the diplomatic consequences, and thus Germany bore responsibility for starting the war, or at least provoking a wider conflict.

Germany began the war by targeting its chief rival, France. Germany saw the French Republic as its principal danger on the European continent as it could mobilize much faster than Russia and bordered Germany's industrial core in the Rhineland. Unlike Britain and Russia, the French entered the war mainly for revenge against Germany, in particular for France's loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871. The German high command knew that France would muster its forces to go into Alsace-Lorraine. Aside from the very unofficial Septemberprogramm, the Germans never stated a clear list of goals that they wanted out of the war.[107]

Western Front

Germany did not want to risk lengthy battles along the Franco-German border and instead adopted the Schlieffen Plan, a military strategy designed to cripple France by invading Belgium and Luxembourg, sweeping down to encircle and crush both Paris and the French forces along the Franco-German border in a quick victory. After defeating France, Germany would turn to attack Russia. The plan required violating the official neutrality of Belgium and Luxembourg, which Britain had guaranteed by treaty. However, the Germans had calculated that Britain would enter the war regardless of whether they had formal justification to do so.[108] At first the attack was successful: the German Army swept down from Belgium and Luxembourg and advanced on Paris, at the nearby river Marne. However, the evolution of weapons over the last century heavily favored defense over offense, especially thanks to the machine gun, so that it took proportionally more offensive force to overcome a defensive position. This resulted in the German lines on the offense contracting to keep up the offensive timetable while correspondingly the French lines were extending. In addition, some German units that were originally slotted for the German far-right were transferred to the Eastern Front in reaction to Russia mobilizing far faster than anticipated. The combined effect had the German right flank sweeping down in front of Paris instead of behind it exposing the German Right flank to the extending French lines and attack from strategic French reserves stationed in Paris. Attacking the exposed German right flank, the French Army and the British Army put up a strong resistance to the defense of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne, resulting in the German Army retreating to defensive positions along the river Aisne. A subsequent Race to the Sea resulted in a long-held stalemate between the German Army and the Allies in dug-in trench warfare positions from Alsace to Flanders.

German attempts to break through failed at the two battles of Ypres (1st/2nd) with huge casualties. A series of allied offensives in 1915 against German positions in Artois and Champagne resulted in huge allied casualties and little territorial change. German Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn decided to exploit the defensive advantages that had shown themselves in the 1915 Allied offensives by attempting to goad France into attacking strong defensive positions near the ancient city of Verdun. Verdun had been one of the last cities to hold out against the German Army in 1870, and Falkenhayn predicted that as a matter of national pride the French would do anything to ensure that it was not taken. He expected that he could take strong defensive positions in the hills overlooking Verdun on the east bank of the river Meuse to threaten the city and the French would launch desperate attacks against these positions. He predicted that French losses would be greater than those of the Germans and that continued French commitment of troops to Verdun would "bleed the French Army white." In February 1916, the Battle of Verdun began, with the French positions under constant shelling and poison gas attack and taking large casualties under the assault of overwhelmingly large German forces. However, Falkenhayn's prediction of a greater ratio of French killed proved to be wrong as both sides took heavy casualties. Falkenhayn was replaced by Erich Ludendorff, and with no success in sight, the German Army pulled out of Verdun in December 1916 and the battle ended.

Eastern Front

While the Western Front was a stalemate for the German Army, the Eastern Front eventually proved to be a great success. Despite initial setbacks due to the unexpectedly rapid mobilisation of the Russian army, which resulted in a Russian invasion of East Prussia and Austrian Galicia, the badly organised and supplied Russian Army faltered and the German and Austro-Hungarian armies thereafter steadily advanced eastward. The Germans benefited from political instability in Russia and its population's desire to end the war. In 1917 the German government allowed Russia's communist Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin to travel through Germany from Switzerland into Russia. Germany believed that if Lenin could create further political unrest, Russia would no longer be able to continue its war with Germany, allowing the German Army to focus on the Western Front.

In March 1917, the Tsar was ousted from the Russian throne, and in November a Bolshevik government came to power under the leadership of Lenin. Facing political opposition, he decided to end Russia's campaign against Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria to redirect Bolshevik energy to eliminating internal dissent. In March 1918, by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Bolshevik government gave Germany and the Ottoman Empire enormous territorial and economic concessions in exchange for an end to war on the Eastern Front. All of present-day Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania was given over to the German occupation authority Ober Ost, along with Belarus and Ukraine. Thus Germany had at last achieved its long-wanted dominance of "Mitteleuropa" (Central Europe) and could now focus fully on defeating the Allies on the Western Front. In practice, however, the forces that were needed to garrison and secure the new territories were a drain on the German war effort.

Colonies

Germany quickly lost almost all its colonies. However, in German East Africa, a guerrilla campaign was waged by the colonial army leader there, General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck. Using Germans and native Askaris, Lettow-Vorbeck launched multiple guerrilla raids against British forces in Kenya and Rhodesia. He also invaded Portuguese Mozambique to gain his forces supplies and to pick up more Askari recruits. His force was still active at war's end.[109]

1918

The defeat of Russia in 1917 enabled Germany to transfer hundreds of thousands of troops from the Eastern to the Western Front, giving it a numerical advantage over the Allies. By retraining the soldiers in new infiltration tactics, the Germans expected to unfreeze the battlefield and win a decisive victory before the army of the United States, which had now entered the war on the side of the Allies, arrived in strength.[110] In what was known as the "kaiserschlacht", Germany converged their troops and delivered multiple blows that pushed back the allies. However, the repeated German offensives in the spring of 1918 all failed, as the Allies fell back and regrouped and the Germans lacked the reserves needed to consolidate their gains. Meanwhile, soldiers had become radicalised by the Russian Revolution and were less willing to continue fighting. The war effort sparked civil unrest in Germany, while the troops, who had been constantly in the field without relief, grew exhausted and lost all hope of victory. In the summer of 1918, the British Army was at its peak strength with as many as 4.5 million men on the western front and 4,000 tanks for the Hundred Days Offensive, the Americans arriving at the rate of 10,000 a day, Germany's allies facing collapse and the German Empire's manpower exhausted, it was only a matter of time before multiple Allied offensives destroyed the German army.[111]

Home front

The concept of "total war" meant that supplies had to be redirected towards the armed forces and, with German commerce being stopped by the Allied naval blockade, German civilians were forced to live in increasingly meagre conditions. First food prices were controlled, then rationing was introduced. During the war about 750,000 German civilians died from malnutrition.[112]

Towards the end of the war, conditions deteriorated rapidly on the home front, with severe food shortages reported in all urban areas. The causes included the transfer of many farmers and food workers into the military, combined with the overburdened railway system, shortages of coal, and the British blockade. The winter of 1916–1917 was known as the "turnip winter", because the people had to survive on a vegetable more commonly reserved for livestock, as a substitute for potatoes and meat, which were increasingly scarce. Thousands of soup kitchens were opened to feed the hungry, who grumbled that the farmers were keeping the food for themselves. Even the army had to cut the soldiers' rations.[113] The morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink.

Spanish Flu Pandemic

The population of Germany was already suffering from outbreaks of disease due to malnutrition due to Allied blockade preventing food imports. Spanish flu arrived in Germany with returning troops. Around 287,000 people died of Spanish flu in Germany between 1918 and 1920 with 50,000 deaths in Berlin alone.

Revolt and demise

Many Germans wanted an end to the war and increasing numbers began to associate with the political left, such as the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the more radical Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), which demanded an end to the war. The entry of the U.S. into the war in April 1917 tipped the long-run balance of power even more in favour of the Allies.

The end of October 1918, in Kiel, in northern Germany, saw the beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Units of the German Navy refused to set sail for a last, large-scale operation in a war which they saw as good as lost, initiating the uprising. On 3 November, the revolt spread to other cities and states of the country, in many of which workers' and soldiers' councils were established. Meanwhile, Hindenburg and the senior generals lost confidence in the Kaiser and his government.

Bulgaria signed the Armistice of Salonica on 29 September 1918. The Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918. Between 24 October and 3 November 1918, Italy defeated Austria-Hungary in the battle of Vittorio Veneto, which forced Austria-Hungary to sign the Armistice of Villa Giusti on 3 November 1918. So, in November 1918, with internal revolution, the Allies advancing toward Germany on the Western Front, Austria-Hungary falling apart from multiple ethnic tensions, its other allies out of the war and pressure from the German high command, the Kaiser and all German ruling kings, dukes, and princes abdicated, and German nobility was abolished. On 9 November, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a republic. The new government led by the German Social Democrats called for and received an armistice on 11 November. It was succeeded by the Weimar Republic.[114] Those opposed, including disaffected veterans, joined a diverse set of paramilitary and underground political groups such as the Freikorps, the Organisation Consul, and the Communists.

Constitution

The Empire was a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy.

The Federal Council (Bundesrat) held sovereignty over the Empire and served as its highest authority.[115] The Bundesrat was a legislative body that possessed the right of legislative initiative (Article VII Nr. 1) and, because all laws required its consent, could effectively veto any bill coming from the Reichstag (Article V).[116] The Bundesrat was able to set guidelines and make organisational changes within the executive branch, act as supreme arbitrator in administrative disputes between states, and serve as constitutional court for states that did not have a constitutional court (Article LXXVI).[116] It was composed of representatives who were appointed by and reported to the state governments.[117]

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag) was a legislative body elected by universal male suffrage that effectively served as parliament. It had the right to propose bills and, with the concurrence of the Bundesrat, approve the state budget annually and the military budget for periods of seven years until 1893, then after that for five years. All laws required the Reichstag's approval to pass.[118] After the constitutional reforms of October 1918, the Reich chancellor, through a change to Article XV, became dependent on the confidence of the Reichstag rather than the emperor.[119]

The emperor (Kaiser) was head of state of the Empire – he was not a ruler. He appointed the chancellor, usually the person able to command the confidence of the Reichstag. The chancellor, in consultation with the emperor, determined the government's broad policy guidelines and presented them to the Reichstag.[118] On the advice of the chancellor, the emperor appointed the ministers and – at least formally – all other imperial officers. All acts of the emperor except for military directives[120] required the countersignature of the chancellor (Article XVII). The emperor was also responsible for signing bills into law, declaring war (which required the consent of the Bundesrat), negotiating peace, making treaties, and calling and adjourning sessions of the Bundesrat and the Reichstag (Articles XI and XII). The emperor was commander-in-chief of the Empire's Army (Article LXIII) and Navy (Article LIII);[116] when exercising his military authority he had plenary power.

The chancellor was head of government and chaired the Bundesrat and the Imperial Government, led the lawmaking process and countersigned all acts of the emperor (except for military directives).[118]

Constituent states

Before unification, German territory (excluding Austria and Switzerland) was made up of 27 constituent states. These states consisted of kingdoms, grand duchies, duchies, principalities, free Hanseatic cities and one imperial territory. The free cities had a republican form of government on the state level, even though the Empire at large was constituted as a monarchy, and so were most of the states. Prussia was the largest of the constituent states, covering two-thirds of the empire's territory.

Several of these states had gained sovereignty following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, and had been de facto sovereign from the mid-1600s onward. Others were created as sovereign states after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Territories were not necessarily contiguous—many existed in several parts, as a result of historical acquisitions, or, in several cases, divisions of the ruling families. Some of the initially existing states, in particular Hanover, were abolished and annexed by Prussia as a result of the war of 1866.

Each component of the German Empire sent representatives to the Federal Council (Bundesrat) and, via single-member districts, the Imperial Diet (Reichstag). Relations between the Imperial centre and the Empire's components were somewhat fluid and were developed on an ongoing basis. The extent to which the German Emperor could, for example, intervene on occasions of disputed or unclear succession was much debated on occasion—for example in the inheritance crisis in Lippe-Detmold.

Unusually for a federation or a nation-state, the German states maintained limited autonomy over foreign affairs and continued to exchange ambassadors and other diplomats (both with each other and directly with foreign nations) for the Empire's entire existence. Shortly after the Empire was proclaimed, Bismarck implemented a convention in which his sovereign would only send and receive envoys to and from other German states as the King of Prussia, while envoys from Berlin sent to foreign nations always received credentials from the monarch in his capacity as German Emperor. In this way, the Prussian foreign ministry was largely tasked with managing relations with the other German states while the Imperial foreign ministry managed Germany's external relations.

Map and table

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other maps

-

Administrative map

-

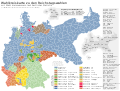

Population density (c. 1885)

-

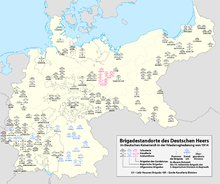

Election constituencies for the Reichstag

-

Detailed map in 1893 with cities and larger towns

Demographics

About 92% of the population spoke German as their first language. The only minority language with a significant number of speakers (5.4%) was Polish (a figure that rises to over 6% when including the related Kashubian and Masurian languages).

The non-German Germanic languages (0.5%), like Danish, Dutch and Frisian, were located in the north and northwest of the empire, near the borders with Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Low German was spoken throughout northern Germany and, though linguistically as distinct from High German (Hochdeutsch) as from Dutch and English, was considered "German", hence also its name. Danish and Frisian were spoken predominantly in the north of the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein and Dutch in the western border areas of Prussia (Hanover, Westphalia, and the Rhine Province).

Polish and other West Slavic languages (6.28%) were spoken chiefly in the east.[c]

A few (0.5%) spoke French, the vast majority of these in the Reichsland Elsass-Lothringen where francophones formed 11.6% of the total population.

1900 census results

| language | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| German[122] | 51,883,131 | 92.05 |

| German and a foreign language | 252,918 | 0.45 |

| Polish | 3,086,489 | 5.48 |

| French | 211,679 | 0.38 |

| Masurian | 142,049 | 0.25 |

| Danish | 141,061 | 0.25 |

| Lithuanian | 106,305 | 0.19 |

| Kashubian | 100,213 | 0.18 |

| Wendish (Sorbian) | 93,032 | 0.16 |

| Dutch | 80,361 | 0.14 |

| Italian | 65,930 | 0.12 |

| Moravian (Czech) | 64,382 | 0.11 |

| Czech | 43,016 | 0.08 |

| Frisian | 20,677 | 0.04 |

| English | 20,217 | 0.04 |

| Russian | 9,617 | 0.02 |

| Swedish | 8,998 | 0.02 |

| Hungarian | 8,158 | 0.01 |

| Spanish | 2,059 | 0.00 |

| Portuguese | 479 | 0.00 |

| Other foreign languages | 14,535 | 0.03 |

| Imperial citizens | 56,367,187 | 100 |

Linguistic maps

-

non-German

Immigration

In the 1860s, Russia removed privileges for German emigrants and placed pressure on German immigrants to assimilate. The majority of German emigrants left Russia after the turn of the century. Some of these ethnic Germans immigrated to Germany.[123]

Religion

Generally, religious demographics of the early modern period hardly changed. Still, there were almost entirely Catholic areas (Lower and Upper Bavaria, northern Westphalia, Upper Silesia, etc.) and almost entirely Protestant areas (Schleswig-Holstein, Pomerania, Saxony, etc.). Confessional prejudices, especially towards mixed marriages, were still common. Bit by bit, through internal migration, religious blending was more and more common. In eastern territories, confession was almost uniquely perceived to be connected to one's ethnicity and the equation "Protestant = German, Catholic = Polish" was held to be valid. In areas affected by immigration in the Ruhr area and Westphalia, as well as in some large cities, religious landscape changed substantially. This was especially true in largely Catholic areas of Westphalia, which changed through Protestant immigration from the eastern provinces.

Politically, the confessional division of Germany had considerable consequences. In Catholic areas, the Centre Party had a big electorate. On the other hand, Social Democrats and Free Trade Unions usually received hardly any votes in the Catholic areas of the Ruhr. This began to change with the secularization arising in the last decades of the German Empire.

| Area | Protestant | Catholic | Other Christian | Jewish | Other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Prussia | 17,633,279 | 64.64 | 9,206,283 | 33.75 | 52,225 | 0.19 | 363,790 | 1.33 | 23,534 | 0.09 |

| Bavaria | 1,477,952 | 27.97 | 3,748,253 | 70.93 | 5,017 | 0.09 | 53,526 | 1.01 | 30 | 0.00 |

| Saxony | 2,886,806 | 97.11 | 74,333 | 2.50 | 4,809 | 0.16 | 6,518 | 0.22 | 339 | 0.01 |

| Württemberg | 1,364,580 | 69.23 | 590,290 | 29.95 | 2,817 | 0.14 | 13,331 | 0.68 | 100 | 0.01 |

| Baden | 547,461 | 34.86 | 993,109 | 63.25 | 2,280 | 0.15 | 27,278 | 1.74 | 126 | 0.01 |

| Alsace-Lorraine | 305,315 | 19.49 | 1,218,513 | 77.78 | 3,053 | 0.19 | 39,278 | 2.51 | 511 | 0.03 |

| Total | 28,331,152 | 62.63 | 16,232,651 | 35.89 | 78,031 | 0.17 | 561,612 | 1.24 | 30,615 | 0.07 |

In Germany's overseas colonial empire, millions of subjects practiced various indigenous religions in addition to Christianity. Over two million Muslims also lived under German colonial rule, primarily in German East Africa.[124]

-

Distribution of Protestants and Catholics in Imperial Germany

-

Distribution of Protestants, Catholics and Jews in Imperial Germany (Meyers Konversationslexikon)

-

Distribution of Jews in Imperial Germany

Coat of arms

Legacy

The defeat and aftermath of the First World War and the penalties imposed by the Treaty of Versailles shaped the positive memory of the Empire, especially among Germans who distrusted and despised the Weimar Republic. Conservatives, liberals, socialists, nationalists, Catholics and Protestants all had their own interpretations, which led to a fractious political and social climate in Germany in the aftermath of the empire's collapse.

Under Bismarck, a united German state had finally been achieved, but it remained a Prussian-dominated state and did not include German Austria as Pan-German nationalists had desired. The influence of Prussian militarism, the Empire's colonial efforts and its vigorous, competitive industrial prowess all gained it the dislike and envy of other nations. The German Empire enacted a number of progressive reforms, such as Europe's first social welfare system and freedom of press. There was also a modern system for electing the federal parliament, the Reichstag, in which every adult man had one vote. This enabled the Social Democrats and the Catholic Centre Party to play considerable roles in the empire's political life despite the continued hostility of Prussian aristocrats.

The era of the German Empire is well remembered in Germany as one of great cultural and intellectual vigour. Thomas Mann published his novel Buddenbrooks in 1901. Theodor Mommsen received the Nobel prize for literature a year later for his Roman history. Painters like the groups Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke made a significant contribution to modern art. The AEG turbine factory in Berlin by Peter Behrens from 1909 was a milestone in classic modern architecture and an outstanding example of emerging functionalism. The social, economic, and scientific successes of this Gründerzeit, or founding epoch, have sometimes led the Wilhelmine era to be regarded as a golden age.

In the field of economics, the "Kaiserzeit" laid the foundation of Germany's status as one of the world's leading economic powers. The iron and coal industries of the Ruhr, the Saar and Upper Silesia especially contributed to that process. The first motorcar was built by Karl Benz in 1886. The enormous growth of industrial production and industrial potential also led to a rapid urbanisation of Germany, which turned the Germans into a nation of city dwellers. More than 5 million people left Germany for the United States during the 19th century.[125]

Sonderweg