Generation Z in the United States

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (November 2024) |

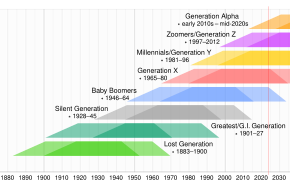

Generation Z (or Gen Z for short), colloquially known as Zoomers,[1][2] is the demographic cohort succeeding Millennials and preceding Generation Alpha.[3] Members of Generation Z, were born between the mid-to-late 1990s and the early 2010s, with the generation typically being defined as those born from 1997 to 2012. In other words, the first wave came of age during the second decade of the twenty-first century,[4] a time of significant demographic change due to declining birthrates, population aging, and immigration.[5] Girls of the early twenty-first century reach puberty earlier than their counterparts from the previous generations.[6] They have higher incidents of eye problems,[7][8] allergies,[9][10] awareness and reporting of mental health issues,[9][11][12] suicide,[13] and sleep deprivation,[14][15] but lower rates of adolescent pregnancy.[16][17][18] They drink alcohol and smoke traditional tobacco cigarettes less often,[19] but are more likely to consume marijuana[20][21] and electronic cigarettes.[22]

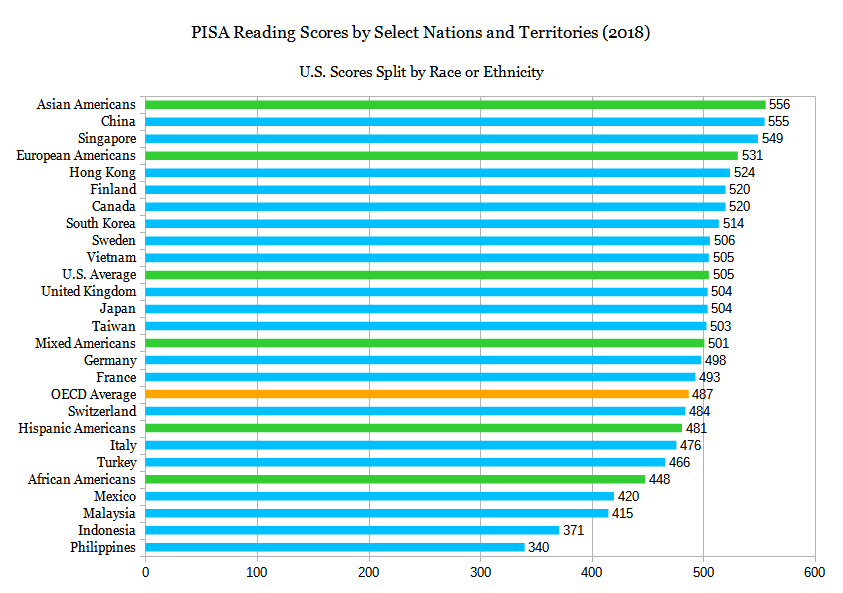

Americans who grew up in the 2000s and 2010s saw gains in IQ points,[23] but loss in creativity.[24] During the 2000s and 2010s, while Western educators in general and American schoolteachers in particular concentrated on helping struggling rather than gifted students,[25] American students of the 2010s had a decline in mathematical literacy and reading proficiency[26] and were trailing behind their counterparts from other countries, especially East Asia.[27][28] They ranked above the OECD average in science and computer literacy, but below average in mathematics.[29]

They became familiar with the Internet and portable digital devices at a young age (as "digital natives"),[4] but are not necessarily digitally literate,[30] and tend to struggle in a digital work place.[31][32] The majority use at least one social-media platform,[33] leading to concerns that spending so much time on social media can distort their view of the world,[34] hamper their social development,[35] harm their mental health,[36][37][38][39][40] expose them to inappropriate materials,[41][42] and cause them to become addicted.[33][43]

Although they trust traditional news media more than what they see online,[44] they tend to be more skeptical of the news than their parents.[45] Young Americans of the late 2010s and early 2020s tend to hold politically left-leaning views.[46][47] However, there is a significant sex gap[48] and most are more interested in advancing their careers than pursuing idealistic political causes.[49][50] As voters, Generation Z's top issue is the economy.[51] As consumers, Generation Z's actual purchases do not reflect their environmental ideals.[52][53] Members of Generation Z, especially women, are also less likely to be religious than older cohorts.[54][55]

On the whole, they are financially cautious,[56][57] and are increasingly interested in alternatives to attending institutions of higher education,[58][59] with young men being primarily responsible for the trend.[60][61] Among those who choose to go to college, grades and standards have fallen because of disruptions in learning due to COVID-19.[62]

Although American youth culture has become highly fragmented by the start of the early twenty-first century, a product of growing individualism,[63] nostalgia is a major feature of youth culture in the 2010s and 2020s.[64][65]

Nomenclature and date range

[edit]While there is no scientific process for deciding when a name has stuck, the momentum is clearly behind Gen Z.

Michael Dimmock, Pew Research Center (2019)[66]

The name Generation Z is a reference to the fact that follows Generation Y (Millennials), which was preceded by Generation X.[67] Other proposed names for the generation include iGeneration,[68] Homeland Generation,[69] Net Gen,[68] Digital Natives,[68] Neo-Digital Natives,[70][71] Pluralist Generation,[68] Centennials,[72] and Post-Millennials.[73] The term Internet Generation is in reference to the fact that the generation is the first to have been born after the mass-adoption of the Internet.[74] The Pew Research Center surveyed the various names for this cohort on Google Trends in 2019 and found that in the U.S., the term Generation Z was overwhelmingly the most popular. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary has an official entry for Generation Z. Zoomer is an informal term used to refer to members of Generation Z, often in an ironic, humorous, or ridiculing tone. It combines the term boomer, referring to baby boomers, with the "Z" from Generation Z. Prior to this, Zoomer was used in the 2000s to describe particularly active baby boomers.[1] Zoomer in its current incarnation skyrocketed in popularity in 2018, when it was used in a 4chan Internet meme ridiculing Gen Z adolescents via a Wojak caricature dubbed a Zoomer.[75] Merriam-Webster's records suggest the use of the term zoomer in the sense of Generation Z dates back at least as far as 2016. It was added to the dictionary in October 2021.[1]

American consulting firm McKinsey & Company uses the phrase "digital aborigines" to refer to people born between 1995 and 2010.[76] Jean Twenge, a psychologist at San Diego State University, calls the people born between born between 1995 and 2012 the "iGeneration" or "iGen" for short.[77][78] In January 2019, Pew Research Center defined "Post-Millennials" as people born from 1997 onward, choosing this date for "different formative experiences" for the purposes of demographic analysis.[79] Common generational experiences include technological developments and socioeconomic trends, including the widespread availability of wireless internet access and high-bandwidth cellular service, and key world events, such as growing up in a world after the September 11th terrorist attacks.[80] During a 2019 analysis, Pew stated that they have yet to set an endpoint to Generation Z, but did use the year 2012 to complete their analysis.[81][82][83][84] In a 2022 article, U.S. Census economists Neil Bennett and Briana Sullivan described Generation Z as those born 1997 to 2013.[85] Psychologists Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt argue that even though the concept of a social generation remains debated, there is evidence for significant differences between the different demographic cohorts.[39] Those born between (on the cusp of) the Millennial generation and Generation Z are commonly known as Zillennials.[86][87]

Arts and culture

[edit]General trends

[edit]

Given their birth years, members of Generation Z have no memory of the time before the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, and the subsequent War on Terror.[89][90][91] Even twenty years after the attacks had taken place, concerns over national security as well as personal safety remain.[89] But most members of Generation Z had their formative years shaped by the 2007–2008 financial crisis.[92] A 2013 survey found that 47% of Generation Z in the United States (considered here to be those between the ages of 14 and 23) were concerned about student debt, while 36% were worried about being able to afford a higher education at all.[93] This generation is facing a growing income gap and a shrinking middle-class, which all have led to increasing stress levels in families.[92] According to Public Relations Society of America, the Great Recession has taught Generation Z to be independent, and has led to an entrepreneurial desire, after seeing their parents and older siblings struggle in the workforce.[94] The COVID-19 pandemic struck when the oldest members of Generation Z was just joining the workforce and the rest were still in school.[88]

Growing up in such uncertain times, Generation Z has come to embrace nostalgia, longing for a purportedly simpler time, or things that remind them of their childhood.[65] As a result, they adapt, hybridize, and modernize older styles of fashion, music, and restaurants, among other things, connecting to the past, but never really abandoning modern electronic devices, which enable them to rummage through the idealized past at will.[95]

Psychologist Jean Twenge argued that as the typical American family has fewer children and as parents pay more attention to each of their children—for example by not allowing them to walk home from school—and to their education, the average American teenager in the mid- to late-2010s tended to be 'slow life-history strategists', meaning they delay taking part in adult activities such as drinking alcohol, having sexual intercourse, or driving.[96][97] Interest in sports has also declined noticeably compared to older generations.[98]

A 2014 study Generation Z Goes to College found that Generation Z students self-identify as being loyal, compassionate, thoughtful, open-minded, responsible, and determined.[99] How they see their Generation Z peers is quite different from their own self-identity. They view their peers as competitive, spontaneous, adventuresome, and curious—all characteristics that they do not see readily in themselves.[99] Like all other cohorts born after the Second World War, Generation Z is culturally individualistic and values social equality. But unlike older living generations of their time, members of Generation Z are much more likely to identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or otherwise non-conforming.[97]

Generation Z today is more likely than young people in the past to try out new cuisines. There is also a growing interest in vegetarian foods.[100]

Museums from across the United States significantly expanded their programs aimed at children, including K-12 students, during the 2000s and 2010s, according to the American Alliance of Museums and the Institute of Museum and Library Services.[101][102] In the fiscal year of 2014, there were more museums in the United States (35,000) than the total numbers of Starbucks locations (11,000) and McDonald's restaurants (14,000) combined.[103]

News media

[edit]According to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, among Americans in their late teens and early 20s, the most common sources of news were social media (especially Facebook and YouTube).[45] Even so, they turn towards well-known news outlets to learn more about current events that interest them.[45] A 2019 survey by Barnes and Nobles Education found that The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and the USA Today are deemed the most trustworthy news sources by Generation Z. They also found that Generation Z consider traditional print media to be the most trustworthy while words of mouth and what they see on social media to be the least trustworthy.[44] Nevertheless, while Generation Z understands the importance of traditional news agencies, they tend to be less loyal than their parents. Young Americans are concerned about the perceived bias, lack of context, negativity, and sensationalism in the news media. American youths today want news stories that are not only fun and meaningful but also accurate and fair.[45] A 2016 poll by Gallup found a decline in trust in the news media across all age groups since (at least) the 1990s, and people aged 18 to 49 are less likely than those 50 years of age or older to trust the media.[104] (Globally, trust in the news media is falling, too.[105])

While visual story-telling has proven to be popular, 58% of Generation Z still prefer text to videos. This number goes up for people who are older.[45] When asked what they would choose if they could have only one subscription, only 7% picked the news while 37% chose a video service and 15% selected music.[105]

Entertainment

[edit]In its 2018 Gen Z Music Consumption & Spending Report, digital media company Sweety High found that Generation Z was listening to more diverse music than generations past. That they tended to switch seamlessly between different genres is significant because music preferences tend to solidify when people are 13 to 14 years old. Spotify was the most popular source of music Generation Z (61%) and terrestrial radio ranked second (55%). YouTube was the preferred platform for music discovery (75%). However, only one in four teens uses it for regular listening, making it less popular than even CDs (38%).[106] TikTok is another major platform for music discovery and for Generation Z to connect with their favorite musicians.[107] Research on popular music from the 1950s to the 2010s has shown that this genre has become louder, while the chords, melodies, and types of sounds used have becoming increasingly homogenized.[108] At the same time, lyrics of the most popular songs have becoming less joyful, sadder, and angrier.[109] Such shifts have occurred due to changing consumer tastes.[109] In particular, the melancholic lyrics of Billie Eilish and Olivia Rodrigo resonate with their generation.[110][111][97] A 2019 poll by Ypulse found that for teenagers (13 to 18), the top musicians were Billie Eilish and Ariana Grande whereas among young adults (19 to 26), the most liked were Taylor Swift and Ariana Grande.[112]

Chinese music video app musical.ly was highly popular among American teens. This app was acquired by ByteDance, sometimes called the "Buzzfeed of China" because it is a hub for stories that go viral on the Internet. Unlike Buzzfeed, however, ByteDance does not employ young staff writers to create its contents; rather, it relies on algorithms equipped with artificial intelligence to collect and modify contents in order to optimize viewership.[113] In 2018, musical.ly was shut down and its users were transferred to TikTok, a competing app developed by ByteDance.[114] Both musical.ly and TikTok enable users to create short videos with popular songs as background music and with numerous special effects,[114] including lip-synchronizing.[113] By the early 2020s, TikTok has become one of the most popular social networks among teenagers and young adults in the United States.[115][116]

The most popular forms of entertainment among Generation Z are playing video games, listening to music, surfing the Internet, and using social media networks.[117][118] According to Asha Choksi, vice president of global research and insights for the educational publisher Pearson, about one in every three members of Generation Z spends at least four hours per day watching videos online.[119] Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that while people aged 15 to 24 spent more time playing video games in 2018, the time spent on computers and televisions remained virtually unchanged.[120]

2020 Nielsen figures revealed that the viewership of children's cable television channels such as Cartoon Network or Nickelodeon continued their steady decline, which was merely decelerated due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many parents and their children to stay at home. On the other hand, streaming services saw healthy growth.[121] Generation Z continues to enjoy comfort television shows, including those popular among older cohorts before, such as The Office (2005–2013) and Friends (1994–2004),[122] as well shows featuring characters roughly their age, like Young Sheldon (2017–2024), and long-running television drama, like Grey's Anatomy (2005–present).[123] Overall, Generation Z would like to see fewer instances of romance and sex in the movies and television programs they watch, and more of friendships, platonic love, and other types of relationships.[124][125] Even so, certain television series such as The Sex Lives of College Girls (2021–present) and movies like Poor Things (2023) have proven to be popular among younger audiences.[125]

A longitudinal analysis of data sets from the Monitoring the Future survey from 1976 to 2016 by a research team headed by psychologist Jean Twenge concluded that "compared with previous generations, teens in the 2010s spent more time online and less time with traditional media, such as books, magazines and television. Time on digital media has displaced time once spent enjoying a book or watching TV." Between 2006 and 2016, usage of digital media, including social networking websites, increased among teenagers of all grade levels while the number of teenagers who read books in their spare time dropped. This secular decline in leisure reading came as a surprise for the researchers because "It's so convenient to read books and magazines on electronic devices like tablets. There's no more going to the mailbox or the bookstore—you just download the magazine issue or book and start reading."[126][127] Twenge further noted that the analyses of the Pew Research Center on reading did not distinguish between reading for school or work and reading for pleasure.[128] But even at school, teachers assign much shorter reading assignments than in the past, and they are less likely to require that students read full-length books.[129] But among teenagers who read for pleasure, dystopian fiction, such as The Hunger Games and Divergent, has been popular among teenagers.[130][131] In addition, the surge in reading during the 2000s coincided with the release of the Harry Potter and Twilight novels.[132]

Demographics

[edit]When Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, as urged by President Lyndon B. Johnson, which abolished national quotas for immigrants and replaced it with a system that admits a fixed number of persons per year based in qualities such as skills and the need for refuge, immigration surged from elsewhere in North America (especially Canada and Mexico), Asia, Central America, and the West Indies.[133] By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Asia and Latin America became the top sources of immigrants to the U.S.[134]

A report by demographer William Frey of the Brookings Institution stated that in the United States, the Millennials are a bridge between the largely Caucasian pre-Millennials (Generation X and their predecessors) and the more diverse post-Millennials (Generation Z and their successors).[135] Frey's analysis of U.S. Census data suggests that as of 2019, 50.9% of Generation Z is white, 13.8% is black, 25.0% Hispanic, and 5.3% Asian. (See figure below.)[136] 29% of Generation Z are children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, compared to 23% of Millennials when they were at the same age. As of 2019, 13.7% of the U.S. population is foreign-born, compared to 9.7% in 1997, when the first members of Generation Z had their birth cries.[134] Indeed, according to the Pew Research Center, in spite of the diminished flow of immigrants to the United States following the Great Recession, Generation Z is the most ethnically diverse yet seen. 52% of this generation is white. 25% is Hispanic. 14% is black, and 4% is Asian.[5] Approximately 4% is multiracial,[5] and this number has risen rapidly between 2000 and 2010.[137] More specifically, the number of Americans who identify as mixed white and black has grown by 134% and those of both white and Asian extraction by 87%.[137] For comparison, 44% of Millennials, 40% of Generation X, and 28% of the Baby Boomers identify as non-white.[138] Research by the demographer Bill Frey suggests that at the national level, Hispanics and Asians are the fastest-growing racial minority groups in the United States while the number of Caucasians under the age of 18 has been declining since 2000.[139] Overall, the number of births to Caucasian women in the United States dropped 7% between 2000 and 2018. Among foreign-born Caucasian women, however, the number of births increased by 1% in the same period. Although the number of births to foreign-born Hispanic women fell from 58% in 2000 to 50% in 2018, the share of births due to U.S.-born Hispanic women increased from 20% in 2000 to 24% in 2018. The number of births to foreign-born Asian women rose from 19% in 2000 to 24% in 2018 while that due to U.S.-born Asian women went from 1% in 2000 to 2% in 2018. In all, between 2000 and 2017, more births were to foreign-born than U.S.-born women.[140]

-

Ethnic minorities under the age of 15 have seen significant growth since the 2000s.

-

Population pyramid of the United States in 2018

Members of Generation Z are slightly less likely to be foreign-born than Millennials;[5] the fact that more American Latinos are born in the U.S. rather than abroad plays a role in making the first wave of Generation Z appear better educated than their predecessors. However, researchers note that this trend could be altered by changing immigration patterns and the younger members of Generation Z choosing alternate educational paths.[141][note 1] 29% of Generation Z are children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, compared to 23% of Millennials when they were at the same age. As of 2019, 13.7% of the U.S. population is foreign-born, compared to 9.7% in 1997, when the first members of Generation Z had their birth cries.[134]

Not only are Americans becoming more and more racially diverse, but racial minorities are also becoming more geographically dispersed than ever before, as new immigrants settle in places other than the large metropolitan areas historically populated by migrants, such as New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. A majority of Generation Z live in urban areas and are less inclined to change address than their predecessors.[5] Similar to the Millennials, roughly two thirds of Generation Z come from households of married parents. By contrast, this living arrangement was essentially the norm for Generation X and the Baby Boomers, at 73% and 85%, respectively.[5]

As a demographic cohort, Generation Z is smaller than the Baby Boomers or their children, the Millennials.[142] (See population pyramid.) According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Generation Z makes up about one quarter of the U.S. population.[143] This demographic change could have social, cultural, and political implications for the decades ahead.[139] Generation Z are usually the children of Generation X,[137][144][145] and sometimes Millennials.[146] Jason Dorsey, who works for the Center of Generational Kinetics, observed that Generation Z is not an extreme version of the Millennials but is rather different, and the differences can largely be attributed to parenting. Like parents from Generation X, members of Generation Z tend to be autonomous and pessimistic. They need validation less than the Millennials and typically become financially literate at an earlier age as many of their parents bore the full brunt of the Great Recession.[147]

Between 2009 and 2016, the number of grandparents raising their grandchildren went up 7%. This is due to a variety of factors, such as military deployment, the growing incarceration of women, drug addictions, and mental health issues. After declining for many years, the number of children in foster care increased 1% in 2013 and 3.4% in 2014. In response, states are sending more and more children who have been taken from their parents to their relatives, drawing from research showing that children tend to be better off being cared for by their own families than strangers and to save taxpayers' money.[148]

Economic trends and outlooks

[edit]Spending and savings habits

[edit]Consumer behavior

[edit]

Modern technology has enabled Generation Z to take advantage of the on-demand economy, defined as "the economic activity created by technology companies that fulfill consumer demand via the immediate provisioning of goods and service."[149] Generation Z tends to value utility and quality over brand name.[150] Authenticity is critical. Having been raised by Generation X and grown up in a recession, members of Generation Z are quick to verify claims. Being consistent users of the Internet and social media in particular, they frequently employ these tools to learn more about a certain product or service they are interested in. Product specifications, vendor ratings, and peer reviews are all important.[151] They tend to be skeptical and will shun firms whose actions and values are contradictory.[52][53] There is a fair amount of interest in in-person shopping rather than over the Internet,[152] a potentially positive development for brick-and-mortar stores.[153] Products with comprehensible ingredients and simple packaging are preferred.[153] In recognition of the tastes of large segments of Generation Z, the next cohort of young consumers, a number of brands, such as M&M's, have moved their advertising and mascots away from the sexual appeal and towards a more anxious but casual style.[154][97] Generation Z's shopping habits are affected by social media networks and their impact on mental health.[155] Gen-Z consumers are less likely to pay a premium for what they want compared to their counterparts from emerging economies.[53] While majorities might signal their support for certain ideals such as "environmental consciousness" to pollsters, actual purchases do not reflect their stated views, as can be seen from their high demand for cheap but not durable clothing ("fast fashion"), or preference for rapid delivery.[52][53] Overall, although more than half say they sought environmentally friendly products, only 38% are willing to pay extra for them.[153] Nor are they willing to shun firms whose owners have reportedly "conservative" values, such as Chick-fil-A, which remains one of the most popular fast-food restaurant chains in the United States among teenagers.[52] While majorities of older cohorts prefer American products, Generation Z is mixed on whether or not to buy goods made in China.[156]

Nostalgia is a major theme of the behavior of consumers from Generation Z. For example, 2000s vintage electronics and fashion are back in vogue by the early 2020s.[158][159] Youths who came of age during the 2010s and 2020s feel nostalgic about "simpler" eras of history they have never experienced due to the uncertainties and stress of modern life, with student loan debts and the threat of terrorism being the top concerns.[64][160] Despite having the reputation for "killing" many things valued by older generations, Millennials and Generation Z are nostalgically preserving Polaroid cameras, vinyl records, needlepoint, and home gardening, to name just some.[157] In fact, while "dumb phones" (or feature phones rather than smartphones) are on the decline around the world, in the U.S., their sales are growing among Generation Z.[161] According to a 2019 YouGov poll, 31% of the U.S. population is willing to pay for music on vinyl, including 26% of Generation Z.[162] As a matter of fact, Millennials and Generation Z have given life to nostalgia as an industry in the late 2010s and early 2020s,[163][164] a trend that coincides with the resurgence of some cultural phenomena of the late 1990s and early 2000s (Y2K), such the television series Friends (1994–2004), something that is well-received among young people despite its age.[158] Nostalgia has also contributed to the anticipation and subsequent commercial success of the summer film Barbie (2023) based on a well-known doll of the same name, even though it was intended for adults rather than children.[165]

Milk consumption has declined among young people and the growing rate of lactose intolerance among the ethnically diverse Generation Z is part of the reason why.[166]

Financial security

[edit]

According to the USA Today, 69% of Generation Z turn to their parents for financial advice compared to 52% of younger Millennials. Friends followed at a distant second place with 24% and 19%, respectively.[167] Unlike their predecessors, members of Generation Z are more cautious of developing financial debt and many are already saving for retirement. Their money-saving habits are reminiscent of those who came of age during the Great Depression.[150] According to Morning Consult, four in ten of those aged 18 to 22 incur no debt at all.[147] However, because a portion spend so much time online playing video games, they make many in-game purchases that add up over time without realizing how much money they are actually spending.[168] In any case, in the second quarter of 2019, the number of people from Generation Z carrying a credit card balance increased by 41% compared to that of 2018 (from 5,483,000 to 7,746,000), as the first wave of this demographic cohort became old enough to take out a mortgage, a loan, or to have credit-card debt, according to TransUnion.[169] In 2019, credit cards became the most common form of debt for Generation Z, overtaking auto loans.[170] This is despite the fact that they grew up during the Great Recession. The financial industry expects continued growth in credit activity by Generation Z, whose rate of credit delinquency is comparable to those of the Millennials and Generation X.[169] According to a 2019 report from the financial firm Northwestern Mutual, student loans were the top source of debt for Generation Z, at 25%. For comparison, mortgages were the top source of debt for the Baby Boomers (28%) and Generation X (30%); for the Millennials, it was credit card bills (25%).[171]

In a study conducted in 2015 the Center for Generational Kinetics found that American members of Generation Z, defined here as those born 1996 and onward, are less optimistic about the state of the US economy than their immediate predecessors, the Millennials.[172] However, Generation Z (58%) is more likely to say they expect to be more successful than their parents were than younger Millennials (52%). Whereas 13% of younger Millennials said they expected to be less successful than their parents, only 10% of Generation Z said the same.[167] A total of 58% of Generation Z said they had not experienced a quarter-life crisis, compared with 46% of younger Millennials.[note 2][167] Americans aged 15 to 21 expect to be financially independent in their early twenties while their parents generally expect them to become so by their mid-twenties. By contrast, about one out of five Millennials expect to still be dependent on their parents beyond the age of 30.[167] While the Millennials tend to prefer flexibility, Generation Z is more interested in certainty and stability.[173] Whereas 23% of Millennials would leave a job if they thought they were not appreciated, only 15% of Generation Z would do the same, according to a Deloitte survey.[147] According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), 77% of Generation Z expects to work harder than previous generations.[138]

Tourism and housing markets

[edit]

Research by the online travel booking company Booking.com reveals that 54% of Generation Z considered environmental impact of their travels to be an important factor, 56% said they would like to stay in environmentally friendly lodging, and 60% were interested in greener modes of transport once they reached their destinations. Meanwhile, the online booking firm Expedia Group found that cost was crucial for 82% of tourists from Generation Z. Therefore, the desire of Generation Z to travel and see the world comes into conflict with what they can afford and their wish to limit their environmental impact.[174]

With regards to the housing market, they typically look for properties with amenities that are comparable to what they experienced as university students.[151] A 2019 Bank of America survey found that over half of people aged 18 to 23 were already saving for a home, with 59% saying they planned to do so within five years. More than one in two members of Generation Z said the top reason why they wanted to own a home was to start a family. For comparison, this number was 40% for the Millennials, 17% for Generation X, and 10% for the Baby Boomers. The survey also found that if they were given $5,000, most members of Generation Z would rather save that money for a down payment rather than spending it on a dream wedding, shopping, or a vacation. A majority of Generation Z was willing to take a second job, attend a less costly university, or move back to their parents' place in order to save money.[56] They are also quite willing to live with people they did not know previously in order to save on rent in large metropolitan areas. According to the personal finance company Credit Karma, 43% of Generation Z said they had had strangers as roommates and 30% said they were willing to move in with roommates they did not know. House cleaning, a potential point of friction, is handled by maids. Nationwide, about one in four Americans have lived with someone they had no prior relationship with.[175]

Data from TransUnion reveals that as the Millennials enter the housing market in large numbers, taking out more mortgages in 2018 than any other living generation, Generation Z's number of new mortgages is also increasing dramatically, from 150,000 in the second quarter of 2018 to 319,000 in the second quarter of 2019, an increase of 112%. Generation Z consumers took out 41% more auto loans in the second quarter of 2019 than in the same period the previous year.[170][note 3] While one out of five Millennial renters said they expected to continue to do so indefinitely, according to a survey by Apartment List, a Freddie Mac study found that 86% of Generation Z desired to own a home by the age of 30. Freddie Mac did note, however, that Generation Z understood the challenges of home prices, making down payments, and student loan debts.[176] According to the real-estate company realtor.com, the first wave of Generation Z was buying homes at about the same rate as their grandparents the Silent Generation in late 2019, when they owned about 2% of the housing market.[177] Judging by the amounts of mortgages, the top housing markets tend to have strong local economies and low cost of living. They also tend to be university towns; many young people prefer to live where they studied.[178] In general, Generation Z appears most interested in owning a home in the Midwest and the South. Broadly speaking, while the Millennials are migrating North, Generation Z is moving South. The median price of a home purchased by Generation Z in 2019 was $160,600 and increasing, but remains lower than that of the Millennials, $256,500.[177]

Employment expectations and prospects

[edit]

Generation Z's top career choices—becoming business people, doctors, engineers, artists, and IT workers—are not that different from generations past.[179] For them, the most important qualities in a job are income, fulfillment, work-life balance, and job security.[57][173][179] In particular, Generation Z prioritizes a work-life balance more than older cohorts and are highly interested in flexible work schedules.[180] Most prefer to work for a medium or large company rather than a startup or a government agency.[138][179]

A Harvard Business Review article from 2015 stated that about 70% of Generation Z was self-employed, e.g. selling things online, and only 12% had "traditional" teen jobs, such as waiting tables.[181] Access to the Internet has made self-employment much easier than it was in the past.[182] A Morgan Stanley report published in 2019, called the Blue Paper, projected that the Millennials and Generation Z have been responsible in a surge in labor participation in the U.S., and that while the U.S. labor force expands, that of other G10 countries will contract. This development alleviates concerns over America's aging population which jeopardizes the solvency of various welfare programs.[183] As of 2019, Millennials and Generation Z accounted for 38% of the American workforce; that number will rise to 58% in the incoming decade.[184]

Due to declining interest in higher education and a tight labor market, in the early 2020s, young Americans could expect to be hired right after graduating high school.[185] In May 2023, the unemployment rate of Americans aged 16 to 24 was 7.5%, the lowest in 70 years.[186] Among teenagers 16 to 19, employment numbers have gone up, though not to the level seen among the Baby Boomers and Generation X when they were teenagers due to a variety of factors, including jobs being automated, outsourced, or given to immigrants, and state governments regulating the job market more tightly.[187] Yet despite a strong labor market and falling inflation, economist Karen Dynan observed that young Americans tend to be pessimistic about their economic prospects, worrying about a possible recession, expensive housing, and the possibility of being laid off.[188]

Anxious about student debt, Generation Z is increasingly interested in alternatives to higher education, such as trade schools, which they and their parents view as quicker and more affordable paths towards prosperity.[189] America's shortage of skilled tradespeople, such as plumbers—whose incomes are in six digits—continues in early 2020s despite the COVID-19 pandemic and despite rising salaries and potential employers offering to pay their recruits during training.[190] Many twenty-first-century jobs are quite sophisticated, involving advanced robotics, additive manufacturing, cloud computing, among other modern technologies, and technologically savvy employees are precisely what employers need. Four-year university degrees are unnecessary; technical or vocational training, or perhaps apprenticeship would do. Generation Z stands to benefit from this "skills gap" in the American economy.[191] Whenever they find themselves short on skills, Generation Z will pick up what they need using the Internet.[57] While there is agreement across generations that it is very important for employees to learn new skills, Millennials and Generation Z are overwhelmingly more likely than Baby Boomers to think that it is the job of employees to train themselves. Baby Boomers tend to think it is the employer's responsibility. Moreover, Millennials and Generation Z (74%) tend to have more colleagues working remotely for a significant portion of their time compared to the Baby Boomers (58%).[184]

Transportation choices

[edit]According to the Pew Research Center, young people are more likely to ride public transit. In 2016, 21% of adults aged 18 to 21 took public transit on a daily, almost daily, or weekly basis. By contrast, this number of all U.S. adults was 11%.[192] Nationwide, about three quarters of American commuters drive their own cars.[193] Also according to Pew, 51% of U.S. adults aged 18 to 29 used a ride-hailing service such as Lyft or Uber in 2018 compared to 28% in 2015. That number for all U.S. adults were 15% in 2015 and 36% in 2018. In general, ride-hailing service users tend to be urban residents, young (18–29), university graduates, and high-income earners ($75,000 a year or more).[194]

Although many in Generation Z no longer view car ownership as a status symbol, a life milestone, or a ticket to freedom,[195] the automotive industry hopes that, like the Millennials, members of Generation Z will later purchase cars in great numbers.[196] Indeed, the number of Generation Z consumers taking out auto loans is rising drastically, from 3,072,000 in the second quarter of 2018 to 4,376,000 in the second quarter of 2019, an increase of 42%.[170] However, 27% of Generation Z consider environmental friendliness to be an important factor, which is higher than their predecessors when they were at the same age. Much more important, though, is the price (77%). Generation Z is not particularly concerned with style or brand; they are more interested in safety. They tend to be more receptive towards self-driving cars.[197] They are also interested in the interior electronic technology of the cars they might purchase. More specifically, they would like to be able to hook up their smartphones to the Bluetooth-capable audio systems and backup cameras.[198]

Education

[edit]Generation Z is revolutionizing the educational system in many aspects. Thanks in part to a rise in the popularity of entrepreneurship and advancements in technology, high schools and colleges across the globe are including entrepreneurship in their curriculum.[199] Generation Z is more likely to search for the information they need on the Internet rather than going through a book and are accustomed to learning by watching videos.[119] A survey by the Pew Research Center found that one in three girls aged 13 to 17 felt excited every day or almost every day about something they learned at school. For boys of the same age group, this number is just above one in five.[200] A 2022 poll by YPulse found that the top five sets of skills Millennials and Generation Z wished they had learned at school were managing mental health, self-defense, survival skills and basic first aid, cooking, and personal finance.[201]

Due to growing pressure from parents and teachers, many school districts in the United States have restricted or ban the use of cellphones in the classroom.[202]

The COVID-19 pandemic has badly disrupted the American education system.[203] In the early 2020s, different school districts report significant shortages of teachers, many of whom have left their positions or the profession itself due to low pay, stressful work environments, the lack of respect for them, and the hostility towards them from some politicians and parents.[204][205] This problem is not new but it mostly affects students in economically deprived areas.[206] Well-endowed suburban schools do not have this problem.[207] Public schools across the United States also presently face falling enrollment due to population decline and defections to private schools and home schooling. As a result, their funding has also fallen.[203]

Many students are finding themselves in the midst of an escalating cultural conflict in which political activists are demanding that books dealing with sensitive topics relating to race and sexuality and those that include coarse language and explicit violence be removed from school libraries.[208][209][210] How to educate students on American history has been a source of fierce debates,[211] as has the teaching of race and sexuality,[212] so much so that following the COVID-19 pandemic, support for parents' rights in deciding their children's educational contents and school choice, or the redirecting of tax money via vouchers to fund private schools chosen by the parents, has grown considerably.[213] Many parents have also used school vouchers to send children to religious or parochial schools, taking advantage of a 2022 Supreme Court ruling.[214] To pacify angry parents and to comply with new state laws, many schoolteachers have opted to remove certain items from their lessons altogether.[215]

K-12

[edit]

Since the 2000s, cursive writing has been de-emphasized in public education.[97] As a result, Generation Z are less likely to read and write in cursive.[216] In fact, the Common Core standards eliminated the requirement that public elementary schools teach cursive writing in 2010. Even so, some states subsequently introduced legislation to teach it in their jurisdiction.[217] There is some evidence indicating the benefits of handwriting—both print and cursive—for the development of cognitive and motor skills; memory and reading comprehension;[218] and for helping students with learning disabilities, such as dyslexia.[219] Unfortunately, lawmakers often cite them out of context, conflating handwriting in general with cursive handwriting.[217] In any case, some 80% of historical records and documents of the United States, such as the correspondence of Abraham Lincoln, was written by hand in cursive, with a sizable amount of modern-day students being unable to read them.[220] Historically, cursive writing was regarded as a mandatory, almost military, exercise. But today, it is thought of as an art form by those who pursue it, both adults and children.[218]

The percentage of American fourth-graders proficient in reading declined during the late 2010s, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.[221] There have been numerous reports in the 2010s on how U.S. students were falling behind their international counterparts in the STEM subjects, especially those from (East) Asia.[27] For example, American schoolchildren put up a mediocre performance on the OECD-sponsored Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), administered every three years to fifteen-year-old students around the world on reading comprehension, mathematics, and science, falling in the middle of the pack of some 71 countries and territories that participated in 2015.[28] In fact, reading scores dropped for all ethnic groups except Asians in the late 2010s, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.[221] This is a source of concern for some because academically gifted students in STEM can have an inordinately positive impact on the national economy. In addition, while American students are less focused on STEM, students from China and India are not only outperforming them but are also coming to the United States in large numbers for higher education.[27] Nevertheless, American students ranked above the OECD average in science and computer literacy, as of 2021.[29]

Despite the general consensus that mathematics education in the United States is mediocre, as indicated by international test scores in the late 2010s, there is strong partisan disagreement over how to address this issue because people are divided between the more traditional teacher-led approach and the student-led or inquiry-based method.[222] An emphasis on rote memorization and speed gives as many as one in three students age five and up mathematical anxiety.[223] Meanwhile, an increasing number of parents opted to send their children to enrichment and accelerated learning after-school or summer programs in the subject. However, many school officials turned their backs on these programs, believing that their primary beneficiaries are affluent white and Asian families, prompting parents to pick private institutions or math circles. Some public schools serving low-income neighborhoods even denied the existence of mathematically gifted students. By the mid-2010s, however, some public schools have begun offering enrichment programs to their students.[224]

Despite the contemporary focus on real-life skills and attempts at reform the curriculum, courses on home economics, also known as family and consumer sciences (FCS), have been on the decline in the early twenty-first century for a variety of reasons, ranging from a shortage of qualified teachers to funding cuts.[225]

Since the early 2010s, a number of U.S. states have taken steps to strengthen teacher education.[226] During the 2000s and 2010s, whereas the Asian polities (especially China, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Singapore) actively sought out gifted students and steered them towards competitive programs, Europe and the United States emphasized inclusion and focused on helping struggling students. Developmental cognitive psychologist David Geary observed that Western educators remained "resistant" to the possibility that even the most talented of schoolchildren needed encouragement and support. In addition, even though it is commonly believed that past a certain IQ benchmark (typically 120), practice becomes much more important than cognitive abilities in mastering new knowledge, recently published research papers based on longitudinal studies, such as the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY) and the Duke University Talent Identification Program, suggest otherwise.[25] According to the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress, 73% of American eighth and twelfth graders had deficient writing skills.[227]

Although passing a high school physics course is linked to graduating from college with a STEM degree,[228] something that is increasingly popular among Generation Z,[58] just under two-fifths of high school graduates did in 2013, according to the American Institute of Physics.[228] With few high school students taking physics, even fewer will study the subject in college and be able to teach it, a vicious cycle. The shortage of high school physics teachers is even more acute than that of mathematics or chemistry teachers.[228]

Many American public schools suffer from inadequate or dated facilities. Some schools even leak when it rains. It is 2017 report on American infrastructure, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave public schools a score of D+.[229] In 2013, less than a third of American public schools have access to broadband Internet service, according to the non-profit EducationSuperHighway. By 2019, however, that number reached 99%. This has increased the frequency of digital learning.[230]

Sex education has been reformed. While traditional lessons involving bananas and condoms remain common, newer approaches that emphasize financial responsibility and character development have been implemented. These reforms play a role in the significant drop in teenage birthrates.[231][note 4]

By the mid-2010s, over four-fifths of American high school students graduate on time and over 70% enroll in college right after graduation. However, nationally, only one-quarter of American high school seniors are able to do grade-level math and only 37% are proficient in reading,[232] yet about half graduate from high school as A students, prompting concerns of grade inflation.[233] In addition, while 93% of middle school students said they want to attend college, only 26% go on to do so and graduate within six years. Critics argue that American high schools are not giving students they need for their future lives and careers. On top of the high costs of collegiate education, the vacancy of potentially millions of skilled jobs that do not require a university degree is making lawmakers reconsider their stance on tertiary education.[232]

High school students bound for university in the United States often take standardized exams such as the ACT or SAT.[235] In 2015, the College Board announced a partnership with the non-profit organization Khan Academy to offer free test-preparation materials to help level the playing field for students from low-income families.[235] Average scores continue to decline as the number of test taker increases.[234] When test centers reopened after the COVID-19 pandemic, ambitious students continue to take the SAT or the ACT to make themselves stand out from the competition regardless of the admissions policies of their preferred schools.[236][237] By 2024, many colleges and universities across the United States reinstated their requirements for standardized tests out of concerns over grade inflation and the unreliability of essays and letters of recommendation.[238][239][237] Indeed, students' scores have been falling on a variety of standardized tests and in all subjects, especially in mathematics,[240] a trend found among students of all backgrounds.[241][242] After the COVID-19 pandemic, the entire cohort of college students in the 2022–23 academic year have lower average grades and mathematical standards.[62]

Post-secondary

[edit]Technical, trades, and vocational schools

[edit]In the late 1980s and early 1990s, high schools across the United States started to take it as their mission to prepare students for higher education.[243] However, this program faltered in the 2010s as institutions of higher education came under heightened skepticism due to rising costs and disappointing results.[244][245] According to the Department of Education, people with technical or vocational training are slightly more likely to be employed than those with a bachelor's degree and significantly more likely to be employed in their fields of specialty.[246] During the late 2010s, the United States was facing a shortage of skilled tradespeople,[246][247] as high-school students were still aiming for colleges and universities.[248] However, things were changing, as more and more members of Generation Z considered alternatives to higher education.[59] Career counselors are in extremely high demand; they are not only called for not just appointments invited to career fairs and orientation sessions for new students.[173] Enrollments in higher education have been on the decline[249][185] as more and more high-school graduates opted for trade schools and vocational training programs.[189]

Colleges and universities

[edit]

Due to low standards and requirements in high school, many Americans are entering institutions of higher learning, including elite schools with deficient reading comprehension skills and are unable and unwilling to complete long reading assignments.[250][251]

As Generation Z enters high school, and they start preparing for college, a primary concern is paying for a college education without acquiring debt. Students report working hard in high school in hopes of earning scholarships and the hope that parents will pay the college costs not covered by scholarships.[252] As of 2019, the total college debt has exceeded $1.5 trillion, and two out of three college graduates are saddled with debt.[58] The average borrower owes $37,000, up $10,000 from ten years before. A 2019 survey found that over 30% of Generation Z and 18% of Millennials said they have considered taking a gap year between high school and college.[253] In order to address the challenges of expensive tuition and student debt, many colleges have diversified their revenue, especially by changing enrollment, recruitment, and retention, and introduced further tuition discounts. Between the academic years 2007-8 and 2018–9, tuition discounts increased significantly. Almost nine in every ten first-time full-time freshmen received some kind of financial aid in the academic year 2017–8.[254] Students also report interest in Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) programs as a means of covering college costs.[252] Indeed, college subsidies are one of the most attractive things about signing up for military service. Another enticement is signing bonuses, whose amounts vary according to specialty.[255]

Domestic undergraduate enrollment has been in decline since 2011,[249] with only 62% of high-school graduates heading for college compared to 70% in 2022.[256] Due to population aging, the number of college-aged people in the United States will fall after 2025, making it easier for people born in the late 2000s and after to get admitted.[257] Indeed, by the mid-2020s, it has already become noticeably easier to get admitted to most colleges and universities in the United States. As of 2024, only 33 colleges and universities admitted less than 10% of applicants.[258] Institutions address challenges of a small pool of prospective students by dropping programs with low student interest, including many in the liberal arts and the humanities, like gender studies and critical race theory,[259] and creating majors for emerging fields, such as artificial intelligence,[260] or professional programs, such as law enforcement,[257] and investing in online learning programs.[260] Demand for very top American institutions, however, will likely remain more or less unchanged.[257]

Members of Generation Z are anxious to pick majors that teach them marketable skills,[58] with an overwhelming majority consider job preparation to be the point of college.[261] Indeed, students and schools increasingly view one another in purely transactional terms.[250] A 2018 Gallup poll on over 32,000 university students randomly selected from 43 schools from across the United States found that just over half (53%) of them thought their chosen major would lead to gainful employment. STEM students expressed the highest confidence (62%) while those in the liberal arts were the least confident (40%). Just over one in three thought they would learn the skills and knowledge needed to become successful in the workplace.[262] Because jobs (that matched what one studied) were so difficult to find in the few years following the Great Recession, the value of getting a liberal arts degree and studying the humanities at university came into question, their ability to develop a well-rounded and broad-minded individual notwithstanding.[263] While the number of students majoring in the humanities has fallen significantly, those in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, or STEM, have risen sharply.[58] Furthermore, those who majored in the humanities and the liberal arts in the 2010s were most likely to regret having done so, whereas those in STEM, especially computer science and engineering, were the least likely.[264] Indeed, STEM workers tend to earn more than their non-STEM counterparts; the difference widens after the bachelor's degree. 54% of people in the life sciences have an advanced degree, making this group the most educated overall among STEM workers. While about half of STEM graduates work in non-STEM jobs, people with collegiate STEM training still tend to earn more, regardless of whether or not their job is STEM-related or not.[265]

Such were the trends before 2020, and the arrival of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States in 2020 merely accelerated the process.[266] The novel pneumonia virus not only wrought havoc on the nation but also caused a severe economic downturn. Consequently, families chose to either delay or avoid sending their children to institutions of higher education altogether.[267] Worse still, colleges and universities have become dependent on foreign students for revenue because they pay full tuition fees and the international restrictions imposed to alleviate the spread of the pandemic mean that this stream of revenue will shrink substantially. On top of that, many schools face lawsuits by students who believed they had received substandard online services in the wake of the pandemic.[266] Numerous institutions, including elite ones, have suspended graduate programs in the humanities and liberal arts due to low student interest and dim employment prospects.[268] About a quarter of American university students failed to graduate within six years in the late 2010s and those who did faced diminishing wage premiums.[269]

Historically, university students were more likely to be male than female. This trend continued into the very early twenty-first century, but by the late 2010s, the situation has reversed. Women are now more likely to enroll in university than men,[270] a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.[60] By the end of the 2020–21 academic year, 59.5% of university students were women. This growing sex gap has been growing for four decades in the United States in parallel with other countries of middle to high income.[60][61] Among those who attend college or university, women are more likely then men to graduate with a degree within six years.[60] On the other hand, the number of women's colleges continues to fall, following a decades-long trend.[271]

Ever since it was introduced in the 1960s, affirmative action has been a controversial topic in the United States.[272][273] In late June 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled against race-based admissions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. UNC.[274] How this affects the demographic makeup of the student bodies of universities and colleges remains unclear, partly because more students have chosen to not specify their race or ethnicity.[275][276] Schools have also been pressure to end legacy admissions as well.[277]

Health issues

[edit]General

[edit]A 2020 study of data from 1999 to 2015 suggests that children living with married parents tended to have lower rates of early-life mortality than those living with unmarried or single parents and non-parents.[278]

Puberty

[edit]For girls born in the United States, the average age of the onset of puberty has been steadily falling compared to the previous century.[279][6] According to a 2019 meta-analysis the age of pubertal onset among girls was between 8.8 and 10.3 years in the United States.[280] Early puberty is associated with a variety of mental health issues (such as anxiety and depression), early sexual activity, and substance abuse, among other problems.[279] Furthermore, factors known for prompting mental health problems—early childhood stress, absent fathers, domestic conflict, and low socioeconomic status—are themselves linked to early pubertal onset.[279] According to Dr. Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah, body-mass index is a strong predictor of precocious puberty.[281] Possible causes of early puberty could be positive, namely improved nutrition,[279] or negative, such as obesity, stress, trauma, exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals, air pollutants, heavy metals.[279][281] Girls of African ancestry on average enter puberty first, followed by those of Hispanic, European, and Asian extraction, in that order. But African-American girls are less likely to face the negative effects of puberty than their counterparts of European descent.[279]

Physical

[edit]Data from the NCES showed that in the academic year 2018–19, 15% of students receiving special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act was suffering from "other health impairments"—such as asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, heart problems, hemophilia, lead poisoning, leukemia, nephritis, rheumatic fever, sickle cell anemia, and tuberculosis.[282]

Vision

[edit]

The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm on a link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices and eyestrain.[7] Symptoms of computer vision syndrome include dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty focusing, headaches. It does not cause vision loss or any other permanent damage, however, and can be alleviated by limiting screen time, taking frequent breaks, adjusting screen brightness, changing the background from bright colors to gray, increasing text sizes, and blinking more often.[8]

Allergies

[edit]While food allergies have been observed by doctors since ancient times and virtually all foods can be allergens, research by the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota found they are becoming increasingly common since the early 2000s. Today, one in twelve American children has a food allergy, with peanut allergy being the most prevalent type.[9] Nut allergies, in general, have quadrupled and shellfish allergies have increased 40% between 2004 and 2019. In all, about 36% of American children have some kind of allergy. By comparison, this number among the Amish in Indiana is 7%. Allergies have also risen ominously in other Western countries. In general, the better developed the country, the higher the rates of allergies.[10] Reasons for this remain poorly understood.[283] One possible explanation, supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is that parents keep their children "too clean for their own good." They recommend exposing newborn babies to a variety of potentially allergenic foods, such as peanut butter, before they reach the age of six months. According to this "hygiene hypothesis," such exposures give the infant's immune system some exercise, making it less likely to overreact. Evidence for this includes the fact that children living on a farm are consistently less likely to be allergic than their counterparts who are raised in the city, and that children born in a developed country to parents who immigrated from developing nations are more likely to be allergic than their parents are.[10]

Mental

[edit]A survey conducted the Fall of 2018 by the American Psychological Association revealed that Generation Z had the weakest mental health of any living generation; some 91% of this demographic cohort reported physical or emotion symptoms associated with stress. Some 54% of workers under the age of 23 said they felt stressed within the last month, compared to 40% for Millennials. The national average was 34%. Experts have not reached a consensus on what might be the cause of this spike in mental health issues. Some suggest it is because of the current state of the world while others argue it is due to increased willingness to discuss such topics. Perhaps both are at play.[173] There is a growing body of evidence that there is a direct link between having access to social media at a young age and weak mental health.[36][37][39][38] Across the United States, university students are besieging the offices of health service workers seeking mental health support.[173] Indeed, Generation Z is the most likely to report having mental health issues than any other living generations.[12] According to The Economist, while teenagers from wealthier households are less likely to have behavioral problems, mental health is an issue that affects every teen regardless of family background. Moreover, the number of university students reporting mental health issues has been rising since the 1950s, if not earlier. Today, one in five American adults suffer from a mental condition, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.[9]

There has been some evidence that COVID-19 lockdowns have accelerated the aging of adolescent brains (as measured by cortical thinning), especially among girls.[284][285]

Anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

[edit]A research paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in June 2019 found a marked increase in suicide rates among adolescents. In 2017, the suicide rate for people aged 15 to 19 was 11.8 per 100,000, the highest point since 2000, when it was 8 per 100,000. In 2017, 6,241 Americans aged 15 to 19 committed suicide, of whom 5,016 were male and 1,225 were female. A flaw in this study is that cause-of-death reports may occasionally be inaccurate. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 30% increase in suicide across all age groups in the United States between 2000 and 2016.[13] There could be a variety of reasons for this. The authors of the JAMA paper suggest an increased willingness by families and coroners to label a death as a result of suicide, depression or opioid usage.[13] Nadine Kaslow, a psychiatrist and behavioral scientist at the Emory University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the paper, pointed to the weakening of familial and other social bonds and the heavy use of modern communications technology, which exposes people to the risk of cyber-bullying.[note 5] She noted that other studies have shown higher suicide rates, too, especially among adolescents and young adults.[286]

The number of American teenagers who suffered from the classic symptoms of depression rose 33% between 2010 and 2015. During the same period, the number of those aged 13 to 21 who committed suicide jumped 31% between 2010 and 2015. Psychologist Jean Twenge and her colleagues found that this growth of mental health issues was not divided along the lines of socioeconomic class, race/ethnicity, or geographical location. Rather, it was associated with spending more time in front of a screen. In general, suicide risk factors—depression, contemplating, planning, and attempting suicide—increase significantly if the subject spends more than two to three hours online. Especially, those who spent five or more hours had their suicide risk factors increase 71%. It is not clear, however, whether depression causes a teenager to spend more time online or the other way around. At the same time, teens who spent more time online were more likely to not have enough sleep, a major predictor of depression.[11] Many teenagers told researchers they used a smartphone or a tablet right before bed, kept the device close, and used it as an alarm clock. But the blue light emitted by these devices, texting, and social networking are known for perturbing sleep. Besides mental problems like depression and anxiety, sleep deprivation is also linked to reduced performance in school and obesity. Parents can address the problem of sleep deprivation simply by imposing limits on screen time and buying simple alarm clocks.[14]

Sleep deprivation

[edit]Research from the American Academy of Pediatrics analyzing responses from the parents of caregivers of 49,050 children aged six to seventeen in the combined 2016-2017 National Survey of Children's Health revealed that only 47.6% of American children slept for nine hours on most days, meaning a significant number was sleep deprived. Compared with children who did not get enough sleep most nights, those who did were 44% more likely to be curious about new things, 33% more likely to finish their homework, 28% more likely to care about their academic performance, and 14% more likely to finish the tasks they started. The researchers identified the risk factors associated with sleep deprivation among children to be the low educational attainment of parents or caregivers, being from families living below the federal poverty line, higher digital media usage, more negative childhood experiences, and mental illnesses.[15] American teenagers share a common habit of having their smartphones on at night, at the expense of the quality of their own sleep.[287]

Cognitive abilities

[edit]According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), between the academic years 2011–12 and 2018–19, the number of students aged three to twenty-one receiving special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) increased from 6.4 million to 7.1 million. Of these, one in three suffered from a specific learning disability, such as having more difficulty than usual with reading or understanding mathematics. Among students enrolled in public schools in that age group, the share receiving special education rose from 13% to 14% during the same time period. Amerindians (18%) and blacks (16%) were the most likely to receive special education while Pacific Islanders (11%) and Asians (7%) were the least likely. After specific learning disabilities, the most common types of learning disorders included speech and language impairment (19%), autism (11%), and developmental delay (7%).[282]

In a 2018 paper, cognitive scientists James R. Flynn and Michael Shayer presented evidence that from the 1990s until the 2010s, the observed gains in IQ during the twentieth century—commonly known as the Flynn effect—had either stagnated (as in the case of Australia, France, and the Netherlands), became mixed (in the German-speaking nations), or reversed (in the Nordic countries and the United Kingdom). This, however, was not the case in South Korea or the United States, as the U.S. continued its historic march towards higher IQ, a rate of 0.38 per decade, at least up until 2014 while South Korea saw its IQ scores growing at twice the average U.S. rate.[23]

While U.S. IQ scores continued to increase, creativity scores, as measured by the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking, were in decline between the 1990s and the late 2000s. Educational psychologist Kyung Hee Kim reached this conclusion after analyzing data samples of kindergartens to high-school students and adults in 1974, 1984, 1990, and 2008, a grand total of 272,599 individuals. Previously, U.S. educational success was attributed to the encouragement of creative thinking, something education reformers in China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan sought to replicate. But U.S. educators decided to go in the opposite direction, emphasizing standardization and test scores at the expense of creativity. On the parenting side, giving children little play time and letting them spend large amounts of time in front of a screen likely contributed to the trend. Creativity has real-life consequences, not just in the arts but also in academia and in life outcomes.[24][288]

Political views and participation

[edit]General trends

[edit]

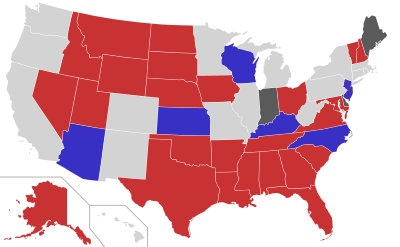

In 2018, Gallup conducted a survey of almost 14,000 Americans from all 50 states and the District of Columbia aged 18 and over on their political sympathies. They found that overall, younger adults tended to lean liberal while older adults tilted conservative. (See chart.) Gallup found little variations by income groups compared to the national average.[289] Youth support for the political left continues to hold during the early 2020s.[48] According to Robert Jones of the Public Religion Research Institute, ethnically and religiously, the Generation Z is much better represented by the Democratic Party while senior Americans are closer to the Republican Party.[290]

However, these broad trends conceal a significant gender divide, with young women under 30 years of age being broadly left-wing and young men being right-leaning on a variety of issues from immigration to sexual harassment.[48][291] A gender gap has been observed since 1980, when women were more likely to vote for the Democratic Part and men for the Republican Party. But this gap has widened during the 2010s and 2020s.[292] According to Gallup, the gap as of early 2024 among voters below the age of 30 was 30 percentage points.[291] Some young men believe that women's progress has come at their expense, that it should be acceptable to discuss men's mental health issues, that men's economic concerns have not been addressed, or that most politicians have ignored them.[293][294] Facing despair and political homelessness, many young men find Donald Trump an appealing alternative.[292][294] They do not necessarily hold socially conservative or patriarchal views, however.[293][295] Many do support gender equality,[293][295] favor keeping abortion legal,[296] and have a high opinion of former President Barack Obama.[296] In contrast, many young women became politically active because of the failed 2016 presidential campaign of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the me-too movement, the Dobbs v. Jackson decision on abortion by the Supreme Court, and the 2024 presidential campaign of Vice President Kamala Harris (after incumbent President Joe Biden announced he would not seek re-election).[47][297][298] In fact, Harris managed to secure the support of many young female voters, who previously only reluctantly voted for Biden or did not vote at all,[299] and her support among women has been rising faster than among young men.[294] Other reasons for the gender gap include young women being better educated and earning more than men in the contemporary American economy.[292][295] In all, American women below the age of 30 have been moving leftward on a number of key political issues while young men have not moved as much.[298] There is little to no gap in terms of educational attainment or race.[299]

As of 2024, the majority of Generation Z does not align with either major political parties of the United States.[47][296] They generally expect more substantive information on policies before casting their vote.[300] Some of the key issues for this cohort are climate change, gender equality, reproductive rights, and gun violence.[47] But the single most important issue for Generation Z is the economy, including inflation, the cost of housing, income inequality, and taxes.[51] Among college students, the top issues are healthcare reforms, the cost of education, and civil rights.[49] Most do not care about Middle Eastern conflicts and the associated protests on college campuses,[49][51] but are more interested in lucrative careers after graduation.[50] Among young men, a majority think that both parties hold extreme views, but that the Republican Party is more so than the Democratic Party.[296]

Social media networks have played a crucial role in how members Generation Z form and share their political views.[47][299] The algorithms of these platforms typically serve contents that reinforce the views of the user and help them mind other like-minded individuals.[298] TikTok has brought Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to the attention of many Gen-Z women.[298] Because they spend so much time on social media networks, people below the age of 30 have little concern over online privacy and national security and many oppose restrictions or bans on popular platforms, such as TikTok.[301] As a result, politicians from both major political parties have been working on appealing to young voters on social networks.[47] This is especially true of the Democratic Party, which is more dependent upon the youth vote.[115] Generation Z's political views have also been shaped by the way they are taught history. Changes to the curriculum of American history during the 2010s, especially in left-leaning states, have led to large numbers young Americans having a low opinion of their country and their historical figures. On the other hand, the decline of belief in American exceptionalism is a long-term trend and is not unique to this cohort.[302]

Elections

[edit]As more and more members of Generation Z reached adulthood during the 2020s, voter turnouts in this cohort has been growing, even though young people are still less likely to vote than older generations. In particular, political participation among young women has jumped, breaking a historical trend in which young men were more likely to vote.[47] Living in an age of political polarization has motivated this cohort to participate in the political process.[97] A survey conducted before the 2020 U.S. presidential election by Barnes and Nobles Education on 1,500 college students nationwide found that just one third of respondents believe who they vote for is "private information" and three quarters of them find it difficult to find unbiased news sources.[44]

2018 was the first year when the majority of voters aged 18 to 24 were members of Generation Z,[97] and they cast 4% of the votes.[303] During the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Millennials and Generation Z voted for Joe Biden by a margin of 20 percentage points. Generation Z cast 8% of the votes that year.[304] Although American voters below the age of 30 helped Joe Biden win, their support for him fell quickly afterwards. By late 2021, only 29% of adults in this age group approved of his performance as president whereas 50% disapproved, a gap of 21 points, the largest of all age groups.[305] In the 2022 midterm election, voters below the age of 30 were the only major age group supporting the Democratic Party, but their numbers were large enough to prevent Republicans from controlling the majority of seats in the Senate.[116] In the 2024 presidential election, Americans aged 18 to 29 voted for Kamala Harris by only a small margin (51% to 47%), according to exit polls conducted by the Associated Press.[306] Compared to 2020, Donald Trump and his Republican Party made considerable gains among young voters, especially young men and European Americans.[307]

Trust in the institutions