Millennials

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

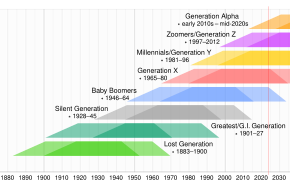

Millennials, also known as Generation Y or Gen Y, are the demographic cohort following Generation X and preceding Generation Z. Researchers and popular media use the early 1980s as starting birth years and the mid-1990s to early 2000s as ending birth years, with the generation typically being defined as people born from 1981 to 1996.[1][2] Most Millennials are the children of Baby Boomers and older Generation X.[3] In turn Millennials are often the parents of Generation Alpha.[4]

As the first generation to grow up with the Internet, Millennials have been described as the first global generation.[5] The generation is generally marked by elevated usage of and familiarity with the Internet, mobile devices, social media, and technology in general.[6] The term "digital natives", which is now also applied to successive generations, was originally coined to describe this generation.[7] Between the 1990s and 2010s, people from developing countries became increasingly well-educated, a factor that boosted economic growth in these countries.[8] In contrast, Millennials across the world have suffered significant economic disruption since starting their working lives, with many facing high levels of youth unemployment in the wake of the Great Recession and the COVID-19 recession.[9][10]

Millennials have been called the "Unluckiest Generation" as the average Millennial has experienced slower economic growth and more recessions since entering the workforce than any other generation in history.[11] They have also been weighed down by student debt and childcare costs.[12] Across the globe, Millenials and subsequent generations have postponed marriage or living together as a couple.[13] Millennials were born at a time of declining fertility rates around the world,[14] and continue to have fewer children than their predecessors.[15][16][17][18] Those in developing countries will continue to constitute the bulk of global population growth.[19] In developed countries, young people of the 2010s were less inclined to have sex compared to their predecessors when they were the same age.[20] Millennials in the West are less likely to be religious than their predecessors, but may identify as spiritual.[14][21]

Terminology and etymology

Members of this demographic cohort are known as Millennials because the oldest became adults around the turn of the millennium.[22] Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe, known for creating the Strauss–Howe generational theory, are widely credited with naming the Millennials.[23] They coined the term in 1987, around the time children born in 1982 were entering kindergarten, and the media were first identifying their prospective link to the impending new millennium as the high school graduating class of 2000.[24] They wrote about the cohort in their books Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069 (1991)[25] and Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000).[24]

In August 1993, an Advertising Age editorial coined the phrase Generation Y to describe teenagers of the day, then aged 13–19 (born 1974–1980), who were at the time defined as different from Generation X.[26] However, the 1974–1980 cohort was later re-identified by most media sources as the last wave of Generation X,[27] and by 2003 Ad Age had moved their Generation Y starting year up to 1982.[28] According to journalist Bruce Horovitz, in 2012, Ad Age "threw in the towel by conceding that Millennials is a better name than Gen Y,"[23] and by 2014, a past director of data strategy at Ad Age said to NPR "the Generation Y label was a placeholder until we found out more about them."[29]

Millennials are sometimes called Echo Boomers, due to them often being the offspring of the Baby Boomers, the significant increase in birth rates from the early 1980s to mid-1990s, and their generation's large size relative to that of Boomers.[30][31][32][33] In the United States, the echo boom's birth rates peaked in August 1990[34][30] and a twentieth-century trend toward smaller families in developed countries continued.[35][36] Psychologist Jean Twenge described Millennials as "Generation Me" in her 2006 book Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – and More Miserable Than Ever Before,[37][38] while in 2013, Time magazine ran a cover story titled Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation.[39] Alternative names for this group proposed include the Net Generation,[40] Generation 9/11,[41] Generation Next,[42] and The Burnout Generation.[43]

Date and age range definitions

Oxford Living Dictionaries describes a Millennial as a person "born between the early 1980s and the late 1990s."[44] Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines Millennial as "a person born in the 1980s or 1990s".[45] More detailed definitions in use are as follows:

Jonathan Rauch, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote for The Economist in 2018 that "generations are squishy concepts", but the 1981 to 1996 birth cohort is a "widely accepted" definition for Millennials.[46] Reuters also state that the "widely accepted definition" is 1981–1996.[47]

The Pew Research Center defines Millennials as the people born from 1981 to 1996, choosing these dates for "key political, economic and social factors", including the 11 September terrorist attacks, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Great Recession, and Internet explosion.[48][49] The United States Library of Congress explains that date ranges are 'subjective' and the traits of each cohort are generalized based around common economic, social, or political factors that happened during formative years. They acknowledge disagreements, complaints over date ranges, generation names, and the overgeneralized "personality" of each generation. They suggest that marketers and journalists use the different groupings to target their marketing to particular age groups. However, they cite Pew's 1981–1996 definition to define Millennials.[50] Various media outlets and statistical organizations have cited Pew's definition including Time magazine,[51] BBC News,[52] The New York Times,[53] The Guardian,[54] the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics,[55] and Statistics Canada.[56]

The Brookings Institution defines the Millennial generation as people born from 1981 to 1996,[57] as does Gallup,[58] Federal Reserve Board,[59] and the American Psychological Association.[60] Encyclopædia Britannica defines Millennials as "the term used to describe a person born between 1981 and 1996, though different sources can vary by a year or two."[61] Although the United States Census Bureau have said that "there is no official start and end date for when Millennials were born"[62] and they do not officially define Millennials,[63] a U.S. Census publication in 2022 noted that Millennials are "colloquially defined as the cohort born from 1981 to 1996", using this definition in a breakdown of Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data.[64]

The Australian Bureau of Statistics uses the years 1981 to 1995 to define Millennials in a 2021 Census report.[65] A report by Ipsos MORI describes the term 'Millennials' as a working title for the circa 15-year birth cohort born around 1980 to 1995, which has 'unique, defining traits'.[66] Governmental institutions such as the UK Department of Health and Social Care have also used 1980 to 1995.[67] Psychologist Jean Twenge defines millennials as those born from 1980 to 1994.[68] Likewise, Australia's McCrindle Research uses the years 1980 to 1994 as Generation Y (millennial) birth years.[69]

A 2023 report by the Population Reference Bureau defines Millennials as those born from 1981 to 1999.[70][71] CNN reports that studies sometimes define Millennials as born between 1980 and 2000.[72] A 2017 BBC report has also referred to this age range in reference to that used by National Records of Scotland.[73] In the UK, the Resolution Foundation uses 1981–2000.[74] The U.S. Government Accountability Office defines Millennials as those born between 1982 and 2000.[75] Sociologist Elwood Carlson, who calls the generation "New Boomers", identified the birth years of 1983–2001, based on the upswing in births after 1983 and finishing with the "political and social challenges" that occurred after the 11 September terrorist acts.[76] Author Neil Howe, co-creator of the Strauss–Howe generational theory, defines Millennials as the cohort born from 1982 to 2004.[77]

The cohorts born during the cusp years before and after Millennials have been identified as "microgenerations" with characteristics of both generations. Names given to these cuspers include Xennials,[78] Generation Catalano,[79] the Oregon Trail Generation;[80] Zennials[81] and Zillennials,[82] respectively. The term Geriatric Millennial gained popularity in 2021 to describe those born in the beginning half of the 1980s between 1980 and 1985. The term has since been used and discussed by various media outlets including Today,[83] CTV News,[84] HuffPost,[85] news.com.au,[86] The Irish Times,[87] and Business Insider.[88]

Psychology

Psychologist Jean Twenge, the author of the 2006 book Generation Me, considers millennials, along with younger members of Generation X, to be part of what she calls "Generation Me".[89] Twenge attributes millennials with the traits of confidence and tolerance, but also describes a sense of entitlement and narcissism, based on NPI surveys showing increased narcissism among millennials[quantify] compared to preceding generations when they were teens and in their twenties.[90][91] Psychologist Jeffrey Arnett of Clark University, Worcester has criticized Twenge's research on narcissism among millennials, stating "I think she is vastly misinterpreting or over-interpreting the data, and I think it's destructive".[92] He doubts that the Narcissistic Personality Inventory really measures narcissism at all. Arnett says that not only are millennials less narcissistic, they're "an exceptionally generous generation that holds great promise for improving the world".[93] A study published in 2017 in the journal Psychological Science found a small decline in narcissism among young people since the 1990s.[94][95]

Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe argue that each generation has common characteristics that give it a specific character with four basic generational archetypes, repeating in a cycle. According to their hypothesis, they predicted millennials would become more like the "civic-minded" G.I. Generation with a strong sense of community both local and global.[24] Strauss and Howe ascribe seven basic traits to the millennial cohort: special, sheltered, confident, team-oriented, conventional, pressured, and achieving. However, Arthur E. Levine, author of When Hope and Fear Collide: A Portrait of Today's College Student, dismissed these generational images as "stereotypes".[96] In addition, psychologist Jean Twenge says Strauss and Howe's assertions are overly deterministic, non-falsifiable, and unsupported by rigorous evidence.[89]

Polling agency Ipsos-MORI warned that the word "millennials" is "misused to the point where it's often mistaken for just another meaningless buzzword" because "many of the claims made about millennial characteristics are simplified, misinterpreted or just plain wrong, which can mean real differences get lost" and that "[e]qually important are the similarities between other generations—the attitudes and behaviors that are staying the same are sometimes just as important and surprising."[97]

Though it is often said that millennials ignore conventional advertising, they are in fact heavily influenced by it. They are particularly sensitive to appeals to transparency, to experiences rather than things, and flexibility.[98]

A 2015 study by Microsoft found that 77% of respondents aged 18 to 24 said yes to the statement, "When nothing is occupying my attention, the first thing I do is reach for my phone," compared to just 10% for those aged 65 and over.[99]

The term ikizurasa (生きづらさ, "pain of living") has been used to denote anxiety experienced by many Japanese Millennials struggling with a sense of disconnectedness and self-blaming, caused by a vast array of issues from unemployment, poverty, family problems, bullying, social withdrawal and mental ill-health.[100]

Cognitive abilities

Intelligence researcher James R. Flynn discovered that back in the 1950s, the gap between the vocabulary levels of adults and children was much smaller than it is in the early twenty-first century. Between 1953 and 2006, adult gains on the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler IQ test were 17.4 points whereas the corresponding gains for children were only 4. He asserted that some of the reasons for this are the surge in interest in higher education and cultural changes. The number of Americans pursuing tertiary qualifications and cognitively demanding jobs has risen significantly since the 1950s. This boosted the level of vocabulary among adults. Back in the 1950s, children generally imitated their parents and adopted their vocabulary. This was no longer the case in the 2000s, when teenagers often developed their own subculture and as such were less likely to use adult-level vocabulary on their essays.[101]

In a 2009 report, Flynn analyzed the results of the Raven's Progressive Matrices test for British fourteen-year-olds from 1980 to 2008. He discovered that their average IQ had dropped by more than two points during that time period. Among those in the higher half of the intelligence distribution, the decline was even more significant, six points. This is a clear case of the reversal of the Flynn effect, the apparent rise in IQ scores observed during the twentieth century. Flynn suspected that this was due to changes in British youth culture. He further noted that in the past, IQ gains had been correlated with socioeconomic class, but this was no longer true.[102]

Psychologists Jean Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, and Ryne A. Sherman analyzed vocabulary test scores on the U.S. General Social Survey () and found that after correcting for education, the use of sophisticated vocabulary has declined between the mid-1970s and the mid-2010s across all levels of education, from below high school to graduate school.[103]

Cultural identity

Computer games and computer culture has [sic] led to a decrease in reading books. The tendency for teachers to now "teach to the test" has also led to a decrease in the capacity to think in lateral ways.

Richard House, Roehampton University, 2009[102]

Political scientist Shirley Le Penne argues that for Millennials, "pursuing a sense of belonging becomes a means of achieving a sense of being needed ... Millennials experience belonging by seeking to impact the world."[104] Educational psychologist Elza Venter believes Millennials are "digital natives" because they have grown up experiencing digital technology and have known it all their lives (). Marc Prensky created the concept of digital natives in response to the understanding that the members of the generation were "native speakers of the digital language of computers, video games and the internet".[105] This generation's older members use a combination of face-to-face communication and computer-mediated communication, while its younger members use mainly electronic and digital technologies for interpersonal communication.[106]

A 2013 survey of almost a thousand Britons aged 18 to 24 found that 62% had a favorable opinion of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and 70% felt proud of their national history.[107] In 2017, research suggested nearly half of 18 to 34 year olds living in the UK had attended a live music event in the previous year.[108]

Having faced the full brunt of the Great Recession, Millennials in Europe tended to be pessimistic about the future direction of their countries, though there were significant differences, the Pew Research Center found in 2014. Millennials from countries with relatively healthy economies such as Germany and the United Kingdom were generally happier than their counterparts from struggling economies, such as Spain, Italy, and Greece. On the other hand, the young were more likely than the old to feel optimistic.[109]

Millennials came of age in a time where the entertainment industry, including music, began to be affected by the Internet.[110][111][112] Using artificial intelligence, Joan Serrà and his team at the Spanish National Research Council studied the massive Million Song Dataset and found that between 1955 and 2010, popular music has gotten louder, while the chords, melodies, and types of sounds used have become increasingly homogenized.[113][114] Indeed, producers seem to be engaging in a "loudness war", with the intention of attracting more and more audience members.[115] While the music industry has long been accused of producing songs that are louder and blander, this is the first time the quality of songs is comprehensively studied and measured.[113] Additional research showed that within the past few decades, popular music has gotten slower; that majorities of listeners young and old preferred older songs rather than keeping up with new ones; that the language of popular songs were becoming more negative psychologically; and that lyrics were becoming simpler and more repetitive, approaching one-word sheets, something measurable by observing how efficiently lossless compression algorithms (such as the LZ algorithm) handled them.[116]

In modern society, there are inevitably people who refuse to conform to the dominant culture and seek to do the exact opposite; given enough time, the anti-conformists will become more homogeneous with respect to their own subculture, making their behavior the opposite to any claims of counterculture. This synchronization occurs even if more than two choices are available, such as multiple styles of beard rather than whether or not to have a beard. Mathematician Jonathan Touboul of Brandeis University who studies how information propagation through society affects human behavior calls this the hipster effect.[118][119]

Once a highly successful genre on radio and then television, soap operas—characterized by melodramatic plots focused on interpersonal affairs and cheap production value—has been declining in viewership since the 1990s. Experts believe that this is due to their failure to attract younger demographics, the tendency of modern audiences to have shorter attention spans, and the rise of reality television in the 1990s. Nevertheless, Internet streaming services do offer materials in the serial format, a legacy of soap operas.[120] However, the availability of such on-demand platforms saw to it that soap operas would never again be the cultural phenomenon they were in the twentieth century, especially among the younger generations, not least because cliffhangers could no longer capture the imagination of the viewers the way they did in the past, when television shows were available as scheduled, not on demand.[121]

Millennial fans, especially girls and women, have been the key factor behind the commercial success of franchises such as Harry Potter, Twilight, and The Hunger Games. More recently, they came out in large numbers for the movie Barbie (2023) and musician Taylor Swift's Eras Tour.[117]

Demographics

Asia

Chinese millennials are commonly called the post-80s and post-90s generations. At a 2015 conference in Shanghai organized by University of Southern California's US–China Institute, millennials in China were examined and contrasted with American millennials. Findings included millennials' marriage, childbearing, and child raising preferences, life and career ambitions, and attitudes towards volunteerism and activism.[122] Due to the one-child policy introduced in the late 1970s, one-child households have become the norm in China, leading to rapid population aging, especially in the cities where the costs of living are much higher than in the countryside.[123]

As a result of cultural ideals, government policy, and modern medicine, there has been severe gender imbalances in China and India. According to the United Nations, in 2018, there were 112 Chinese males aged 15 to 29 for every hundred females in that age group. That number in India was 111. China had a total of 34 million excess males and India 37 million, more than the entire population of Malaysia. Such a discrepancy fuels loneliness epidemics, human trafficking (from elsewhere in Asia, such as Cambodia and Vietnam), and prostitution, among other societal problems.[124]

Singapore's birth rate has fallen below the replacement level of 2.1 since the 1980s before stabilizing by during the 2000s and 2010s.[125] (It reached 1.14 in 2018, making it the lowest since 2010 and one of the lowest in the world.[126]) Government incentives such as the baby bonus have proven insufficient to raise the birth rate. Singapore's experience mirrors those of Japan and South Korea.[125]

Vietnam's median age in 2018 was 26 and rising. Between the 1970s and the late 2010s, life expectancy climbed from 60 to 76.[127] It is now the second highest in Southeast Asia. Vietnam's fertility rate dropped from 5 in 1980 to 3.55 in 1990 and then to 1.95 in 2017. In that same year, 23% of the Vietnamese population was 15 years of age or younger, down from almost 40% in 1989.[128] Other rapidly growing Southeast Asian countries, such as the Philippines, saw similar demographic trends.[129]

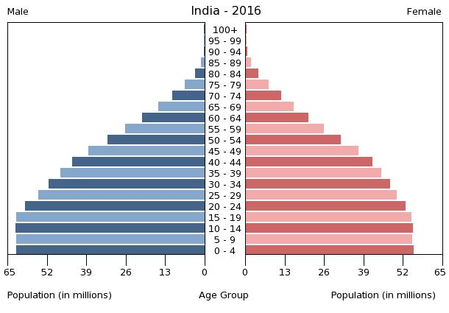

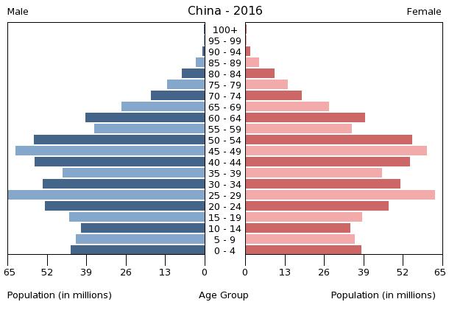

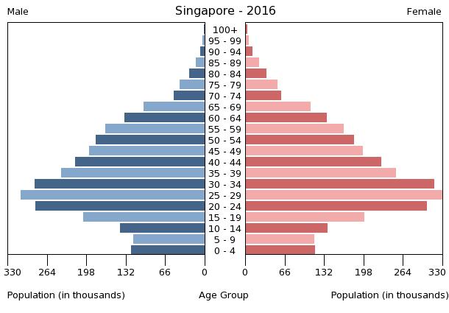

- Population pyramids of India, China, and Singapore in 2016

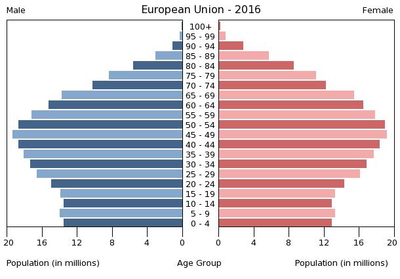

Europe

From about 1750 to 1950, most of Western Europe transitioned from having both high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates. By the late 1960s and 1970s, the average woman had fewer than two children, and, although demographers at first expected a "correction", such a rebound came only for a few countries. Despite a bump in the total fertility rates (TFR) of some European countries in the very late twentieth century (the 1980s and 1990s), especially France and Scandinavia, it returned to replacement level only in Sweden (reaching a TFR of 2.14 in 1990, up from 1.68 in 1980),[130] along with Ireland[131] and Iceland;[132] the bump in Sweden was largely due to improving economic output and the generous, far-reaching family benefits granted by the Nordic welfare system,[133] while in France it was mostly driven by older women realizing their dreams of motherhood. For Sweden, the increase in the fertility rate came with a rise in the birth rate (going from 11.7 in 1980 to 14.5 in 1990),[134] which slowed down and then stopped for a brief period to the aging of the Swedish population[135] caused by the decline in birth rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s. To this day, France and Sweden still have higher fertility rates than most of Europe, and both almost reached replacement level in 2010 (2.03[136] and 1.98[134] respectively).

At first, falling fertility is due to urbanization and decreased infant mortality rates, which diminished the benefits and increased the costs of raising children. In other words, it became more economically sensible to invest more in fewer children, as economist Gary Becker argued. (This is the first demographic transition.) Falling fertility then came from attitudinal shifts. By the 1960s, people began moving from traditional and communal values towards more expressive and individualistic outlooks due to access to and aspiration of higher education, and to the spread of lifestyle values once practiced only by a tiny minority of cultural elites. (This is the second demographic transition.) Although the momentous cultural changes of the 1960s leveled off by the 1990s, the social and cultural environment of the very late twentieth-century was quite different from that of the 1950s. Such changes in values have had a major effect on fertility. Member states of the European Economic Community saw a steady increase in not just divorce and out-of-wedlock births between 1960 and 1985 but also falling fertility rates. In 1981, a survey of countries across the industrialized world found that while more than half of people aged 65 and over thought that women needed children to be fulfilled, only 35% of those between the ages of 15 and 24 (younger Baby Boomers and older Generation X) agreed.[14] In the early 1980s, East Germany, West Germany, Denmark, and the Channel Islands had some of the world's lowest fertility rates.[137]

At the start of the twenty-first century, Europe suffers from an aging population. This problem is especially acute in Eastern Europe, whereas in Western Europe, it is alleviated by international immigration. In addition, an increasing number of children born in Europe has been born to non-European parents. Because children of immigrants in Europe tend to be about as religious as they are, this could slow the decline of religion (or the growth of secularism) in the continent as the twenty-first century progresses.[138] In the United Kingdom, the number of foreign-born residents stood at 6% of the population in 1991. Immigration subsequently surged and has not fallen since (as of 2018). Research by the demographers and political scientists Eric Kaufmann, Roger Eatwell, and Matthew Goodwin suggest that such a fast ethno-demographic change is one of the key reasons behind public backlash in the form of national populism across the rich liberal democracies, an example of which is the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum (Brexit).[139]

Italy is a country where the problem of an aging population is especially acute. The fertility rate dropped from about four in the 1960s down to 1.2 in the 2010s. This is not because young Italians do not want to procreate. Quite the contrary, having many children is an Italian ideal. But its economy has been floundering since the Great Recession of 2007–08, with the youth unemployment rate at a staggering 35% in 2019. Many Italians have moved abroad—150,000 did in 2018—and many are young people pursuing educational and economic opportunities. With the plunge in the number of births each year, the Italian population is expected to decline in the next five years. Moreover, the Baby Boomers are retiring in large numbers, and their numbers eclipse those of the young people taking care of them. Only Japan has an age structure more tilted towards the elderly.[140]

Greece also suffers from a serious demographic problem as many young people are leaving the country in search of better opportunities elsewhere in the wake of the Great Recession. This brain drain and a rapidly aging population could spell disaster for the country.[141]

Overall, E.U. demographic data shows that the number of people aged 18 to 33 in 2014 was 24% of the population, with a high of 28% for Poland and a low of 19% for Italy.[109]

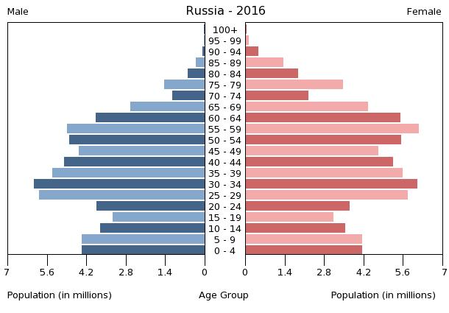

As a result of the shocks due to the decline and dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia's birth rates began falling in the late 1980s while death rates have risen, especially among men.[142] In the early 2000s, Russia had not only a falling birth rate but also a declining population despite having an improving economy.[143] Between 1992 and 2002, Russia's population dropped from 149 million to 144 million. According to the "medium case scenario" of the U.N.'s Population Division, Russia could lose another 20 million people by the 2020s.[142]

Europe's demographic reality contributes to its economic troubles. Because the European baby boomers failed to replace themselves, by the 2020s and 2030s, dozens of European nations will find their situation even tougher than before.[18]

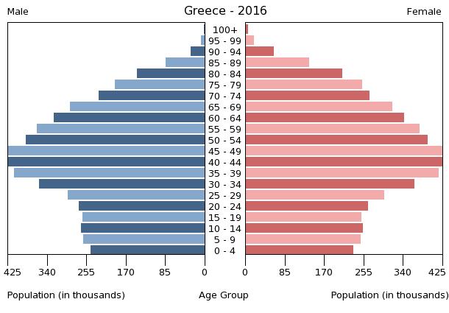

- Population pyramids of Italy, Greece, and Russia in 2016

Oceania

Australia's total fertility rate has fallen from above three in the post-war era, to about replacement level (2.1) in the 1970s to below that in the late 2010s. However, immigration has been offsetting the effects of a declining birthrate. In the 2010s, among the residents of Australia, 5% were born in the United Kingdom, 3% from China, 2% from India, and 1% from the Philippines. 84% of new arrivals in the fiscal year of 2016 were below 40 years of age, compared to 54% of those already in the country. Like other immigrant-friendly countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Australia's working-age population is expected to grow till about 2025. However, the ratio of people of working age to retirees (the dependency ratio) has gone from eight in the 1970s to about four in the 2010s. It could drop to two by the 2060s, depending in immigration levels.[144] "The older the population is, the more people are on welfare benefits, we need more health care, and there's a smaller base to pay the taxes," Ian Harper of the Melbourne Business School told ABC News (Australia).[145] While the government has scaled back plans to increase the retirement age, to cut pensions, and to raise taxes due to public opposition, demographic pressures continue to mount as the buffering effects of immigration are fading away.[144]

North America

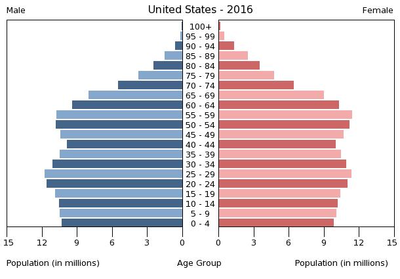

Historically, the early Anglo-Protestant settlers in the seventeenth century were the most successful group, culturally, economically, and politically, and they maintained their dominance till the early twentieth century. Commitment to the ideals of the Enlightenment meant that they sought to assimilate newcomers from outside of the British Isles, but few were interested in adopting a pan-European identity for the nation, much less turning it into a global melting pot. But in the early 1900s, liberal progressives and modernists began promoting more inclusive ideals for what the national identity of the United States should be. While the more traditionalist segments of society continued to maintain their Anglo-Protestant ethnocultural traditions, universalism and cosmopolitanism started gaining favor among the elites. These ideals became institutionalized after the Second World War, and ethnic minorities started moving towards institutional parity with the once dominant Anglo-Protestants.[146] The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart–Celler Act), passed at the urging of President Lyndon B. Johnson, abolished national quotas for immigrants and replaced it with a system that admits a fixed number of persons per year based in qualities such as skills and the need for refuge. Immigration subsequently surged from elsewhere in North America (especially Canada and Mexico), Asia, Central America, and the West Indies.[147] By the mid-1980s, most immigrants originated from Asia and Latin America. Some were refugees from Vietnam, Cuba, Haiti, and other parts of the Americas while others came illegally by crossing the long and largely undefended U.S.-Mexican border. At the same time, the postwar baby boom and subsequently falling fertility rate seemed to jeopardize America's social security system as the Baby Boomers retire in the twenty-first century.[148] Provisional data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reveal that U.S. fertility rates have fallen below the replacement level of 2.1 since 1971. (In 2017, it fell to 1.765.)[149]

Millennial population size varies, depending on the definition used. Using its own definition, the Pew Research Center estimated that millennials comprised 27% of the U.S. population in 2014.[109] In the same year, using dates ranging from 1982 to 2004, Neil Howe revised the number to over 95 million people in the U.S.[150] In a 2012 Time magazine article, it was estimated that there were approximately 80 million U.S. millennials.[151] The United States Census Bureau, using birth dates ranging from 1982 to 2000, stated the estimated number of U.S. millennials in 2015 was 83.1 million people.[152]

In 2017, fewer than 56% millennial were non-Hispanic whites, compared with more than 84% of Americans in their 70s and 80s, 57% had never been married, and 67% lived in a metropolitan area.[153] According to the Brookings Institution, millennials are the "demographic bridge between the largely white older generations (pre-millennials) and much more racially diverse younger generations (post-millennials)."[154]

By analyzing data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Pew Research Center estimated that millennials, whom they define as people born between 1981 and 1996, outnumbered baby boomers, born from 1946 to 1964, for the first time in 2019. That year, there were 72.1 million millennials compared to 71.6 million baby boomers, who had previously been the largest living adult generation in the country. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows that about 62 million millennials were born in the United States, compared to 55 million members of Generation X, 76 million baby boomers, and 47 million from the Silent Generation. Between 1981 and 1996, an average of 3.9 million millennial babies were born each year, compared to 3.4 million average Generation X births per year between 1965 and 1980. But millennials continue to grow in numbers as a result of immigration and naturalization. In fact, millennials form the largest group of immigrants to the United States in the 2010s. Pew projected that the millennial generation would reach around 74.9 million in 2033, after which mortality would outweigh immigration.[155] Yet 2020 would be the first time millennials (who are between the ages of 24 and 39) find their share of the electorate shrink as the leading wave of Generation Z (aged 18 to 23) became eligible to vote. In other words, their electoral power peaked in 2016. In absolute terms, however, the number of foreign-born millennials continues to increase as they become naturalized citizens. In fact, 10% of American voters were born outside the country by the 2020 election, up from 6% in 2000. The fact that people from different racial or age groups vote differently means that this demographic change will influence the future of the American political landscape. While younger voters hold significantly different views from their elders, they are considerably less likely to vote. Non-whites tend to favor candidates from the Democratic Party while whites by and large prefer the Republican Party.[156]

As of the mid-2010s, the United States is one of the few developed countries that does not have a top-heavy population pyramid. In fact, as of 2016, the median age of the U.S. population was younger than that of all other rich nations except Australia, New Zealand, Cyprus, Ireland, and Iceland, whose combined population is only a fraction of the United States. This is because American baby boomers had a higher fertility rate compared to their counterparts from much of the developed world. Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, and South Korea are all aging rapidly by comparison because their millennials are smaller in number than their parents. This demographic reality puts the United States at an advantage compared to many other major economies as the millennials reach middle age: the nation will still have a significant number of consumers, investors, and taxpayers.[18]

According to the Pew Research Center, "Among men, only 4% of millennials [ages 21 to 36 in 2017] are veterans, compared with 47%" of men in their 70s and 80s, "many of whom came of age during the Korean War and its aftermath."[153] Some of these former military service members are combat veterans, having fought in Afghanistan or Iraq.[157] As of 2016, millennials are the majority of the total veteran population.[158] According to the Pentagon in 2016, 19% of Millennials are interested in serving in the military, and 15% have a parent with a history of military service.[159]

Economic prospects and trends

Trends suggest developments in artificial intelligence and robotics will not result in mass unemployment, but can actually create high-skilled jobs. However, in order to take advantage of this situation, people need to hone skills that machines have not yet mastered, such as teamwork.[160][161]

By analyzing data from the United Nations and the Global Talent Competitive Index, KDM Engineering found that As of 2019[update], the top five countries for international high-skilled workers are Switzerland, Singapore, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Sweden. Factors taken into account included the ability to attract high-skilled foreign workers, business-friendliness, regulatory environment, the quality of education, and the standard of living. Switzerland is best at retaining talents due to its excellent quality of life. Singapore is home to a world-class environment for entrepreneurs. And the United States offers the most opportunity for growth due to the sheer size of its economy and the quality of higher education and training.[162] As of 2019, these are also some of the world's most competitive economies, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). In order to determine a country or territory's economic competitiveness, the WEF considers factors such as the trustworthiness of public institutions, the quality of infrastructure, macro-economic stability, the quality of healthcare, business dynamism, labor market efficiency, and innovation capacity.[163]

From 2000–2020, before the COVID pandemic, economic activities tended to concentrate in the large metropolitan areas, such as San Francisco, New York, London, Tokyo and Sydney. Productivity increased enormously as knowledge workers agglomerated. The pandemic led to an increase in remote work, more so in developed countries, aided by technology.[164]

Using a variety of measures, economists have reached the conclusion that the rate of innovation and entrepreneurship has been declining across the Western world between the early 1990s and early 2010s, when it leveled off. In the case of the U.S., one of the most complex economies in existence, economist Nicholas Kozeniauskas explained that "the decline in entrepreneurship is concentrated among the smart" as the share of entrepreneurs with university degrees in that country more than halved between the mid-1980s and the mid-2010s. There are many possible reasons for this: population aging, market concentration, and zombie firms (those with low productivity but are kept alive by subsidies). While employment has become more stable and more suitable, modern economies are so complex they are essentially ossified, making them vulnerable to disruptions.[165]

Education

Global trends

From the late 1990s to the late 2010s, education transformed the economic realities of countries worldwide. As the people from developing nations became better educated, they close the gap between them and the developed world. Hence Westerners lost their relative advantage in education, as the world saw more people with high-school diplomas than ever before. The number of people with Bachelor's degree and advanced degrees grew significantly as well. Westerners who only passed secondary school had their income cut in real terms during that same period while those with university degrees had incomes that barely increased on average. The fact that many jobs are suitable for remote work due to modern technology further eroded the relative advantage of education in the Western world, resulting in a backlash against immigration and globalization.[8]

As more and more women became educated in the developing world, more leave the rural areas for the cities, enter the work force and compete with men, sparking resentment among men in those countries.[8]

For information on public support for higher education (for domestic students) in the OECD in 2011, see chart below.

In Europe

In Sweden, universities are tuition-free, as is the case in Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Finland. However, Swedish students typically graduate very indebted due to the high cost of living in their country, especially in the large cities such as Stockholm. The ratio of debt to expected income after graduation for Swedes was about 80% in 2013. In the U.S., despite incessant talk of student debt reaching epic proportions, that number stood at 60%. Moreover, about seven out of eight Swedes graduate with debt, compared to one half in the U.S. In the 2008–09 academic year, virtually all Swedish students take advantage of state-sponsored financial aid packages from a govern agency known as the Centrala Studiestödsnämnden (CSN), which include low-interest loans with long repayment schedules (25 years or until the student turns 60). In Sweden, student aid is based on their own earnings whereas in some other countries, such as Germany or the United States, such aid is premised on parental income as parents are expected to help foot the bill for their children's education. In the 2008–09 academic year, Australia, Austria, Japan, the Netherlands, and New Zealand saw an increase in both the average tuition fees of their public universities for full-time domestic students and the percentage of students taking advantage of state-sponsored student aid compared to 1995. In the United States, there was an increase in the former but not the latter.[166]

In 2005, judges in Karlsruhe, Germany, struck down a ban on university fees as unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the constitutional right of German states to regulate their own higher education systems. This ban was introduced in order to ensure equality of access to higher education regardless of socioeconomic class. Bavarian Science Minister Thomas Goppel told the Associated Press, "Fees will help to preserve the quality of universities." Supporters of fees argued that they would help ease the financial burden on universities and would incentivize students to study more efficiently, despite not covering the full cost of higher education, an average of €8,500 as of 2005. Opponents believed fees would make it more difficult for people to study and graduate on time.[167] Germany also suffered from a brain drain, as many bright researchers moved abroad while relatively few international students were interested in coming to Germany. This has led to the decline of German research institutions.[168]

In the 1990s, due to a combination of financial hardship and the fact that universities elsewhere charged tuition, British universities pressed the government to allow them to take in fees. A nominal tuition fee of £1,000 was introduced in autumn 1998. Because not all parents would be able to pay all the fees in one go, monthly payment options, loans, and grants were made available. Some were concerned that making people pay for higher education may deter applicants. This turned out not to be the case. The number of applications fell by only 3% in 1998, and mainly due to mature students rather than 18-year-olds.[169]

In 2012, £9,000 worth of student fees were introduced. Despite this, the number of people interested in pursuing higher education grew at a faster rate than the UK population. In 2017, almost half of young people in England had received higher education by the age of 30. Prime Minister Tony Blair introduced the goal of having half of young Britons having a university degree in 1999, though the 2010 deadline was missed.[170] What the Prime Minister did not realize, however, is that an oversupply of young people with high levels of education historically precipitated periods of political instability and unrest in various societies, from early modern Western Europe and late Tokugawa Japan to the Soviet Union, modern Iran, and the United States.[171][172] In any case, demand for higher education in the United Kingdom has remained strong throughout the early 21st century, driven by the need for high-skilled workers from both the public and private sectors. There has been, however, a widening gender gap. As of 2017, women were more likely to attend or to have attended university than men, by 55% against 43%, a difference of 12 percentage points.[170]

Oceania

In Australia, university tuition fees were introduced in 1989. Regardless, the number of applicants has risen considerably. By the 1990s, students and their families were expected to pay 37% of the cost, up from a quarter in the late 1980s. The most expensive subjects were law, medicine, and dentistry, followed by the natural sciences, and then by the arts and social studies. Under the new funding scheme, the Government of Australia also capped the number of people eligible for higher education, enabling schools to recruits more well-financed (though not necessarily bright) students.[169]

North America

According to the Pew Research Center, 53% of American millennials attended or were enrolled in university in 2002. For comparison, the number of young people attending university was 44% in 1986.[173] By the 2020s, 39% of millennials had at least a bachelor's degree, more than the Baby Boomers at 25%, the Economist reports.[174]

In the United States today, high school students are generally encouraged to attend college or university after graduation while the options of technical school and vocational training are often neglected.[175] Historically, high schools separated students on career tracks, with programs aimed at students bound for higher education and those bound for the workforce. Students with learning disabilities or behavioral issues were often directed towards vocational or technical schools. All this changed in the late 1980s and early 1990s thanks to a major effort in the large cities to provide more abstract academic education to everybody. The mission of high schools became preparing students for college, referred to as "high school to Harvard."[176] However, this program faltered in the 2010s, as institutions of higher education came under heightened skepticism due to high costs and disappointing results. People became increasingly concerned about debts and deficits. No longer were promises of educating "citizens of the world" or estimates of economic impact coming from abstruse calculations sufficient. Colleges and universities found it necessary to prove their worth by clarifying how much money from which industry and company funded research, and how much it would cost to attend.[177]

Because jobs (that suited what one studied) were so difficult to find in the few years following the Great Recession, the value of getting a liberal arts degree and studying the humanities at an American university came into question, their ability to develop a well-rounded and broad-minded individual notwithstanding.[178] As of 2019, the total college debt has exceeded US$1.5 trillion, and two out of three college graduates are saddled with debt.[173] The average borrower owes US$37,000, up US$10,000 from ten years before. A 2019 survey by TD Ameritrade found that over 18% of millennials (and 30% of Generation Z) said they have considered taking a gap year between high school and college.[179]

In 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published research (using data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances) demonstrating that after controlling for race and age cohort families with heads of household with post-secondary education who were born before 1980 there have been wealth and income premiums, while for families with heads of household with post-secondary education but born after 1980 the wealth premium has weakened to point of statistical insignificance (in part because of the rising cost of college) and the income premium while remaining positive has declined to historic lows (with more pronounced downward trajectories with heads of household with postgraduate degrees).[180] Quantitative historian Peter Turchin noted that the United States was overproducing university graduates—he termed this elite overproduction—in the 2000s and predicted, using historical trends, that this would be one of the causes of political instability in the 2020s, alongside income inequality, stagnating or declining real wages, growing public debt. According to Turchin, intensifying competition among graduates, whose numbers were larger than what the economy could absorb, leads to political polarization, social fragmentation, and even violence as many become disgruntled with their dim prospects despite having attained a high level of education. He warned that the turbulent 1960s and 1970s could return, as having a massive young population with university degrees was one of the key reasons for the instability of the past.[172]

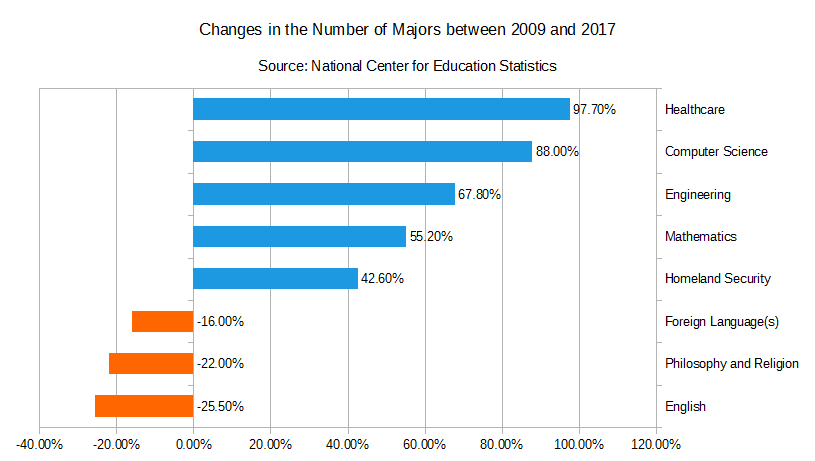

According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, students were turning away from liberal arts programs. Between 2012 and 2015, the number of graduates in the humanities dropped from 234,737 to 212,512. Consequently, many schools have relinquished these subjects, dismissed faculty members, or closed completely.[181] Data from the National Center for Education Statistics revealed that between 2008 and 2017, the number of people majoring in English plummeted by just over a quarter. At the same time, those in philosophy and religion fell 22% and those who studied foreign languages dropped 16%. Meanwhile, the number of university students majoring in homeland security, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), and healthcare skyrocketed. (See figure below.)[182]

According to the U.S. Department of Education, people with technical or vocational trainings are slightly more likely to be employed than those with a bachelor's degree and significantly more likely to be employed in their fields of specialty.[175] The United States currently suffers from a shortage of skilled tradespeople.[175]

Despite the fact that educators and political leaders, such as President Barack Obama, have been trying to years to improve the quality of STEM education in the United States, and that various polls have demonstrated that more students are interested in these subjects, graduating with a STEM degree is a different kettle of fish altogether.[183] According to The Atlantic, 48% of students majoring in STEM dropped out of their programs between 2003 and 2009.[184] Data collected by the University of California, Los Angeles, (UCLA) in 2011 showed that although these students typically came in with excellent high school GPAs and SAT scores, among science and engineering students, including pre-medical students, 60% changed their majors or failed to graduate, twice the attrition rate of all other majors combined. Despite their initial interest in secondary school, many university students find themselves overwhelmed by the reality of a rigorous STEM education.[183] Some are mathematically unskilled,[183][184] while others are simply lazy.[183] The National Science Board raised the alarm all the way back in the mid-1980s that students often forget why they wanted to be scientists and engineers in the first place. Many bright students had an easy time in high school and failed to develop good study habits. In contrast, Chinese, Indian, and Singaporean students are exposed to mathematics and science at a high level from a young age.[183] Moreover, according education experts, many mathematics schoolteachers were not as well-versed in their subjects as they should be, and might well be uncomfortable with mathematics.[184] Given two students who are equally prepared, the one who goes to a more prestigious university is less likely to graduate with a STEM degree than the one who attends a less difficult school. Competition can defeat even the top students. Meanwhile, grade inflation is a real phenomenon in the humanities, giving students an attractive alternative if their STEM ambitions prove too difficult to achieve. Whereas STEM classes build on top of each other—one has to master the subject matter before moving to the next course—and have black and white answers, this is not the case in the humanities, where things are a lot less clear-cut.[183]

In 2015, educational psychologist Jonathan Wai analyzed average test scores from the Army General Classification Test in 1946 (10,000 students), the Selective Service College Qualification Test in 1952 (38,420), Project Talent in the early 1970s (400,000), the Graduate Record Examination between 2002 and 2005 (over 1.2 million), and the SAT Math and Verbal in 2014 (1.6 million). Wai identified one consistent pattern: those with the highest test scores tended to pick the physical sciences and engineering as their majors while those with the lowest were more likely to choose education. (See figure below.)[185][186]

During the 2010s, the mental health of American graduate students in general was in a state of crisis.[187]

Historical knowledge

A February 2018 survey of 1,350 individuals found that 66% of the American millennials (and 41% of all U.S. adults) surveyed did not know what Auschwitz was,[188] while 41% incorrectly claimed that 2 million Jews or fewer were killed during the Holocaust, and 22% said that they had never heard of the Holocaust.[189] Over 95% of American millennials were unaware that a portion of the Holocaust occurred in the Baltic states, which lost over 90% of their pre-war Jewish population, and 49% were not able to name a single Nazi concentration camp or ghetto in German-occupied Europe.[190][191] However, at least 93% surveyed believed that teaching about the Holocaust in school is important and 96% believed the Holocaust happened.[192]

The YouGov survey found that 42% of American millennials have never heard of Mao Zedong, who ruled China from 1949 to 1976 and was responsible for the deaths of 20–45 million people; another 40% are unfamiliar with Che Guevara.[193][194]

Health and welfare

According to a 2018 report from Cancer Research UK, millennials in the United Kingdom are on track to have the highest rates of overweight and obesity, with current data trends indicating millennials will overtake the Baby boomer generation in this regard, making millennials the heaviest generation since current records began. Cancer Research UK reports that more than 70% of millennials will be overweight or obese by ages 35–45, in comparison to 50% of Baby boomers who were overweight or obese at the same ages.[195][196][197]

According to the National Strokes Association, the risk of having a stroke is increasing among young adults (those in their 20s and 30s) and even adolescents. During the 2010s, there was a 44% increase in the number of young people hospitalized for strokes. Health experts believe this development is due to a variety of reasons related to lifestyle choices, including obesity, smoking, alcoholism, and physical inactivity. Obesity is also linked to hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol levels. CDC data reveals that during the mid-2000s, about 28% of young Americans were obese; this number rose to 36% a decade later. Up to 80% of strokes can be prevented by making healthy lifestyle choices while the rest are due to factors beyond a person's control, namely age and genetic defects (such as congenital heart disease). In addition, between 30% and 40% of young patients suffered from cryptogenic strokes, or those with unknown causes.[198]

According to a 2019 report from the American College of Cardiology, the prevalence of heart attacks among Americans under the age of 40 increased by an average rate of two percent per year in the previous decade. About one in five patients suffered from a heart attack came from this age group. This is despite the fact that Americans in general were less likely to suffer from heart attacks than before, due in part to a decline in smoking. The consequences of having a heart attack were much worse for young patients who also had diabetes. Besides the common risk factors of heart attacks, namely diabetes, high blood pressure, and family history, young patients also reported marijuana and cocaine intake, but less alcohol consumption.[199]

Drug addiction and overdoses adversely affect millennials more than prior generations with overdose deaths among millennials increasing by 108% from 2006 to 2015.[200] In the United States, millennials and older zoomers represented a majority of all opioid overdose deaths in 2021.[201] The leading cause of death for people aged 25–44 in 2021 were drug overdoses (classified as poisonings by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) with overdose deaths being triple that of the second and third leading causes of death; suicide and traffic accidents, respectively.[202][203] This represents a major shift as traffic accidents typically constituted a majority of accidental deaths for prior generations.[204]

Millennials struggle with dental and oral health. More than 30% of young adults have untreated tooth decay (the highest of any age group), 35% have trouble biting and chewing, and some 38% of this age group find life in general "less satisfying" due to teeth and mouth problems.[205]

Sports and fitness

Fewer American millennials follow sports than their Generation X predecessors,[206] with a McKinsey survey finding that 38 percent of millennials in contrast to 45 percent of Generation X are committed sports fans.[207] However, the trend is not uniform across all sports; the gap disappears for National Basketball Association, Ultimate Fighting Championship, English Premier League and college sports.[206] For example, a survey in 2013 found that engagement with mixed martial arts had increased in the 21st century and was more popular than boxing and wrestling for Americans aged 18 to 34 years old, in contrast to those aged 35 and over who preferred boxing.[208] In the United States, while the popularity of American football and the National Football League has declined among millennials, the popularity of Association football and Major League Soccer has increased more among millennials than for any other generation, and as of 2018 was the second most popular sport among those aged 18 to 34.[209][210]

Regarding the sports participation by millennials, activities that are popular or emerging among millennials including boxing,[211] cycling,[212][213] running,[214] and swimming,[215] while other sports including golf are facing decline among millennials.[216][217] The Physical Activity Council's 2018 Participation Report found that in the U.S., millennials were more likely than other generations to participate in water sports such as stand-up paddling, board-sailing and surfing. According to the survey of 30,999 Americans, which was conducted in 2017, approximately half of U.S. millennials participated in high caloric activities while approximately one quarter were sedentary. The 2018 report from the Physical Activity Council found millennials were more active than Baby Boomers in 2017. Thirty-five percent of both millennials and Generation X were reported to be "active to a healthy level", with millennials' activity level reported as higher overall than that of Generation X in 2017.[218][219]

Political views and participation

Millennials are reshaping political discourse, showing evolving attitudes towards governance, social issues, and economic policies. Their increasing political participation and distinct generational identity signify a transformative phase in contemporary politics, with potential long-term implications for national and global political trends.

American millennials exhibit a complex spectrum of political views, paralleling broader generational shifts in attitudes toward social, economic, and political issues. Surveys indicate a significant portion of millennials' political views align with their parents, though a notable fraction express more liberal tendencies. Key issues for US millennials include support for same-sex marriage, varying attitudes towards the LGBT community, and a more moderate stance on political ideologies compared to older generations. Millennials in the United States demonstrate increasing skepticism towards capitalism, with a preference for socialism seen in younger segments of the demographic. Canadian millennials played a crucial role in the election of Justin Trudeau, driven by social and economic liberal values. Despite historically low political participation, the 2015 federal election saw a surge in youth voter turnout, influenced by Trudeau's progressive campaign promises.

British millennials, characterized by a relative political disengagement in their early years, have shown liberal tendencies on social and economic matters, favoring individual liberty and limited government intervention. Significant political moments like the Brexit referendum mobilized young voters, displaying a strong preference for remaining in the European Union, highlighting generational divides in political priorities and attitudes.

Across Europe, millennials are part of a larger shift towards post-materialist values, emphasizing environmentalism, social liberalism, and global citizenship. This generational shift is contributing to changing political landscapes, challenging traditional party alignments and contributing to the rise of new political movements. French millennials, while exempt from mandatory military service, still engage in a Defense and Citizenship Day, reflecting continued engagement with national civic duties. A significant majority support the reintroduction of some form of national service, reflecting broader desires for national cohesion and integration.

Preferred modes of transport

Millennials in the U.S. were initially not keen on getting a driver's license or owning a vehicle thanks to new licensing laws and the state of the economy when they came of age, but the oldest among them have already begun buying cars in great numbers. In 2016, millennials purchased more cars and trucks than any living generation except the Baby Boomers; in fact, millennials overtook Baby Boomers in car ownership in California that year.[223] A working paper by economists Christopher Knittel and Elizabeth Murphy then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the National Bureau of Economic Research analyzed data from the U.S. Department of Transportation's National Household Transportation Survey, the U.S. Census Bureau, and American Community Survey in order to compare the driving habits of the Baby Boomers, Generation X, and the oldest millennials (born between 1980 and 1984). That found that on the surface, the popular story is true: American millennials on average own 0.4 fewer cars than their elders. But when various factors—including income, marital status, number of children, and geographical location—were taken into account, such a distinction ceased to be. In addition, once those factors are accounted for, millennials actually drive longer distances than the Baby Boomers. Economic forces, namely low gasoline prices, higher income, and suburban growth, result in millennials having an attitude towards cars that is no different from that of their predecessors. An analysis of the National Household Travel Survey by the State Smart Transportation Initiative revealed that higher-income millennials drive less than their peers probably because they are able to afford the higher costs of living in large cities, where they can take advantage of alternative modes of transportation, including public transit and ride-hailing services.[224]

According to the Pew Research Center, young people are more likely to ride public transit. In 2016, 21% of adults aged 18 to 21 took public transit on a daily, almost daily, or weekly basis. By contrast, this number of all U.S. adults was 11%.[225] Nationwide, about three quarters of American commuters drive their own cars.[226] Also according to Pew, 51% of U.S. adults aged 18 to 29 used Lyft or Uber in 2018 compared to 28% in 2015. That number for all U.S. adults were 15% in 2015 and 36% in 2018. In general, users tend to be urban residents, young (18–29), university graduates, and high income earners ($75,000 a year or more).[227]

Religious beliefs

Millennials often describe themselves as "spiritual but not religious" and will sometimes turn to astrology, meditation or mindfulness techniques possibly to seek meaning or a sense of control.[21] According to 2015 analysis of the European Values Study in the Handbook of Children and Youth Studies "the majority of young respondents in Europe claimed that they belonged to a Christian denomination", and "in most countries, the majority of young people believe in God".[228] However, according to the same analysis a "dramatic decline" in religious affiliation among young respondents happened in Great Britain, Sweden, France, Italy and Denmark. By contrast an increase in religious affiliation happened among young respondents in Russia, Ukraine, and Romania.[228]

According to a 2013 YouGov poll of almost a thousand Britons between the ages of 18 and 24, 56% said they had never attended a place of worship, other than for a wedding or a funeral. 25% said they believed in God, 19% in a "spiritual greater power" while 38% said they did not believe in God nor any other "greater spiritual power". The poll also found that 14% thought religion was a "cause of good" in the world while 41% thought religion was "the cause of evil". 34% answered "neither".[107] The British Social Attitudes Survey found that 71% of British 18–24 year-olds were not religious, with just 3% affiliated to the once-dominant Church of England, and 5% say they are Catholics, and 14% say they belong to other Christian denomination.[229]

In the U.S., millennials are the least likely to be religious when compared to older generations.[230] There is a trend towards irreligion that has been increasing since the 1940s.[231] According to a 2012 study by Pew Research, 32 percent of Americans aged 18–29 are irreligious, as opposed to 21 percent aged 30–49, 15 percent aged 50–64, and only 9 percent born aged 65 and above.[232] A 2005 study looked at 1,385 people aged 18 to 25 and found that more than half of those in the study said that they pray regularly before a meal. One-third said that they discussed religion with friends, attended religious services, and read religious material weekly. Twenty-three percent of those studied did not identify themselves as religious practitioners.[233] A 2010 Pew Research Center study on millennials shows that of those between 18 and 29 years old, only 3% of these emerging adults self-identified as "atheists" and only 4% self-identified as "agnostics". While 68% of those between 18 and 29 years old self-identified as "Christians" (43% self-identified as Protestants and 22% self-identified as Catholics). Overall, 25% of millennials are "Nones" and 75% are religiously affiliated.[234] In 2011, social psychologists Jason Weeden, Adam Cohen, and Douglas Kenrick analyzed survey data sets from the American general public and university undergraduates and discovered that sociosexual tendencies—that is, mating strategies—play a more important role in determining the level of religiousness than any other social variables. In fact, when controlled for family structure and sexual attitudes, variables such as age, sex, and moral beliefs on sexuality substantially drop in significance in determining religiosity. In the context of the United States, religiousness facilitates seeking and maintaining high-fertility, marriage-oriented, heterosexual monogamous relationships. As such, the central goals of religious attendance are reproduction and child-rearing. However, this Reproductive Religiosity Model does not necessarily apply to other countries. In Singapore, for example, they found no relationships between the religiousness of Buddhists and their attitudes towards sexuality.[235]

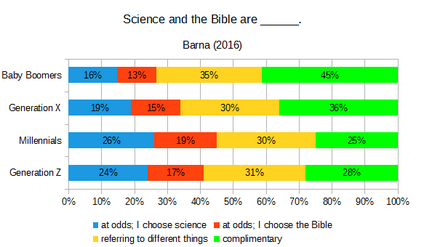

A 2016 U.S. study found that church attendance during young adulthood was 41% among Generation Z, 18% for the millennials, 21% for Generation X, and 26% for the Baby Boomers when they were at the same age.[236] A 2016 survey by Barna and Impact 360 Institute on about 1,500 Americans aged 13 and up suggests that the proportion of atheists and agnostics was 21% among Generation Z, 15% for millennials, 13% for Generation X, and 9% for Baby Boomers. 59% of Generation Z were Christians (including Catholics), as were 65% for the millennials, 65% for Generation X, and 75% for the Baby Boomers. 41% of teens believed that science and the Bible are fundamentally at odds with one another, with 27% taking the side of science and 17% picking religion. For comparison, 45% of millennials, 34% of Generation X, and 29% of the Baby Boomers believed such a conflict exists. 31% of Generation Z believed that science and religion refer to different aspects of reality, on par with millennials and Generation X (both 30%), and above the Baby Boomers (25%). 28% of Generation Z thought that science and religion are complementary, compared to 25% of millennials, 36% of Generation X, and 45% for Baby Boomers.[237]

Social tendencies

Social circles

In March 2014, the Pew Research Center issued a report about how "millennials in adulthood" are "detached from institutions and networked with friends". The report said millennials are somewhat more upbeat than older adults about America's future, with 49% of millennials saying the country's best years are ahead, though they're the first in the modern era to have higher levels of student loan debt and unemployment.[238][239]

Courtship behavior

In many countries, people have since the mid-twentieth century been increasingly looking for mates of the same socioeconomic status and educational attainment. The phenomenon of preferring mates with characteristics similar to one's own is known as assortative mating. Part of the reason growing economic and educational assortative mating was economic in nature. Innovations which became commercially available in the late twentieth century such as the washing machine and frozen food reduced the amount of time people needed to spend on housework, which diminished the importance of domestic skills.[240] Moreover, by the early 2000s, it was less feasible for a couple with one spouse having no more than a high-school diploma to earn about the national average; on the other hand, couples both of whom had at least a bachelor's degree could expect to make a significant amount above the national average. People thus had a clear economic incentive to seek out a mate with at least as high a level of education in order to maximize their potential income.[241] Another incentive for this kind of assortative mating lies in the future of the offspring. People have since the mid-twentieth century increasingly wanted intelligent and well-educated children, and marrying bright people who make a lot of money goes a long way in achieving that goal.[240][242] Couples in the early twenty-first century tend to hold egalitarian rather than traditional views on gender roles. Modern marriage is more about companionship rather than bread-winning for the man and homemaking for the woman.[242] American and Chinese youths are increasingly choosing whether or not to marry according to their personal preferences rather than family, societal, or religious expectations.[242][13]

As of 2016, 54% of Russian millennials were married.[243]

According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, the number of people getting married for the first time went from 23.8 million in 2013 to 13.9 million in 2019, a 41% drop. Meanwhile, the marriage rate continued its decline, 6.6 per 1,000 people, a 33% drop compared to 2013. These trends are due to multiple reasons. The one-child policy, introduced in 1979, has curbed the number of young people in China. On top of that, the traditional preference for sons has resulted in a marked gender imbalance; as of 2021, China has over 30 million "surplus" men.[13]

In the 1990s, the Chinese government reformed higher education in order to increase access, whereupon significantly more young people, a slight majority of whom being women, have received a university degree. Consequently, many young women are now gainfully employed and financially secure. Traditional views on gender roles dictate that women be responsible for housework and childcare, regardless of their employment status. Workplace discrimination against women (with families) is commonplace; for example, an employer might be more skeptical towards a married woman with one child, fearing she might have another (as the one-child policy was rescinded in 2016) and take more maternity leave. Altogether, there is less incentive for young women to marry.[13]

For young Chinese couples in general, the cost of living, especially the cost of housing in the big cities, is a serious obstacle to marriage. In addition, Chinese millennials are less keen on marrying than their predecessors as a result of cultural change.[13]

Writing for The Atlantic in 2018, Kate Julian reported that among the countries that kept track of the sexual behavior of their citizens—Australia, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States—all saw a decline in the frequency of sexual intercourse among teenagers and young adults. Although experts disagree on the methodology of data analysis, they do believe that young people today are less sexually engaged than their elders, such as the baby boomers, when they were their age. This is despite the fact that online dating platforms allow for the possibility of casual sex, the wide availability of contraception, and the relaxation of attitudes towards sex outside of marriage.[20]

A 2020 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by researchers from Indiana University in the United States and the Karolinska Institutet from Sweden found that during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, young Americans had sexual intercourse less frequently than in the past. Among men aged 18 to 24, the share of the sexually inactive increased from 18.9% between 2000 and 2002 to 30.9% between 2016 and 2018. Women aged 18 to 34 had sex less often as well. Reasons for this trend are manifold. People who were unemployed, only had part-time jobs, and students were the most likely to forego sexual experience while those who had higher income were stricter in mate selection. Psychologist Jean Twenge, who did not participate in the study, suggested that this might be due to "a broader cultural trend toward delayed development", meaning various adult activities are postponed. She noted that being economically dependent on one's parents discourages sexual intercourse. Other researchers noted that the rise of the Internet, computer games, and social media could play a role, too, since older and married couples also had sex less often. In short, people had many options. A 2019 study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine found a similar trend in the United Kingdom.[244][245] Although this trend precedes the COVID-19 pandemic, fear of infection is likely to fuel the trend the future, study co-author Peter Ueda told Reuters.[246]

In a 2019 poll, the Pew Research Center found that about 47% American adults believed dating had become more difficult within the last decade or so, while only 19% said it became easier and 33% thought it was the same. Majorities of both men (65%) and women (43%) agreed that the #MeToo movement posed challenges for the dating market while 24% and 38%, respectively, thought it made no difference. In all, one in two of single adults were not looking for a romantic relationship. Among the rest, 10% were only interested in casual relationships, 14% wanted committed relationships only, and 26% were open to either kind.[247] Among younger people (18 to 39), 27% wanted a committed relationship only, 15% casual dates only, and 58% either type of relationship. For those between the ages of 18 and 49, the top reasons for their decision to avoid dating were having more important priorities in life (61%), preferring being single (41%), being too busy (29%), and pessimism about their chances of success (24%).[248]

While most Americans found their romantic partners with the help of friends and family, younger adults were more likely to encounter them online than their elders, with 21% of those aged 18 to 29 and 15% of those aged 30 to 49 saying they met their current partners this way. For comparison, only 8% of those aged 50 to 64 and 5% of those aged 65 and over did the same. People aged 18 to 29 were most likely to have met their current partners in school while adults aged 50 and up were more likely to have met their partners at work. Among those in the 18 to 29 age group, 41% were single, including 51% of men and 32% of women. Among those in the 30 to 49 age group, 23% were single, including 27% of men and 19% of women. This reflects the general trend across the generations that men tend to marry later (and die earlier) than women.[248]

Most single people, regardless of whether or not they were interested in dating, felt little to no pressure from their friends and family to seek a romantic partner. Young people, however, were under significant pressure compared to the sample average or older age groups. 53% of single people aged 18 to 29 thought there was at least some pressure from society on them to find a partner, compared to 42% for people aged 30 to 49, 32% for people aged 50 to 64, and 21% for people aged 50 to 64.[247]

Family life and offspring

According to the Brookings Institution, the number of American mothers who never married ballooned between 1968, when they were extremely rare, and 2008, when they became much more common, especially among the less educated. In particular, in 2008, the number of mothers who never married with at least 16 years of education was 3.3%, compared to 20.1% of those who never graduated from high school. Unintended pregnancies were also higher among the less educated.[249]