Fall River, Massachusetts

Fall River | |

|---|---|

Fall River city center in September 2007 | |

| Nicknames: "The Scholarship City", "The River", "Spindle City", "Where the River Falls" "The City of the Dinner Pail"[1] | |

| Mottoes: "We'll Try"[2] | |

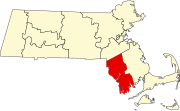

Location of Fall River in Bristol County, Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 41°42′05″N 71°09′20″W / 41.70139°N 71.15556°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Bristol |

| Settled | 1670 |

| Incorporated (town) | 1803 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1854 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Paul Coogan |

| • City council[3] | Joseph Camara President Linda Pereira Vice President Shawn E. Cadime Michelle Dionne Bradford L. Kilby Laura-Jean Washington Andrew Raposo Leo O. Pelletier |

| Area | |

• Total | 40.24 sq mi (104.22 km2) |

| • Land | 33.12 sq mi (85.79 km2) |

| • Water | 7.12 sq mi (18.43 km2) |

| Elevation | 72 ft (37 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 94,000 |

| • Density | 2,837.91/sq mi (1,095.73/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 02720–02724 |

| Area code | 508/774 |

| FIPS code | 25-23000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0612595 |

| Website | www |

Fall River is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. Fall River's population was 94,000 at the 2020 United States census,[5] making it the tenth-largest city in the state. It abuts the Rhode Island state line with Tiverton, RI to its south.

Located along the eastern shore of Mount Hope Bay at the mouth of the Taunton River, the city gained recognition during the 19th century as a leading textile manufacturing center in the United States. While the textile industry has long since moved on, its impact on the city's culture and landscape is still prominent. Fall River's official motto is "We'll Try", dating back to the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1843. Nicknamed The Scholarship City after Irving Fradkin founded Dollars for Scholars there in 1958, mayor Jasiel Correia introduced the "Make It Here" slogan as part of a citywide rebranding effort in 2017.[6]

Fall River is known for the Lizzie Borden case, the Fall River cult murders, Portuguese culture, its numerous 19th-century textile mills and Battleship Cove, home of the world's largest collection of World War II naval vessels (including the battleship USS Massachusetts). Fall River has its city hall located over an interstate highway.

History

[edit]Colonial period to 1800s

[edit]

At the time of the establishment of the Plymouth Colony in 1620, the area that would one day become Troy City was inhabited by the Pocasset Wampanoag tribe, affiliated with the Pokanoket Confederacy headquartered at Mount Hope in what is now Bristol, Rhode Island. The "falling" river that the city's name refers to is the Quequechan River (pronounced "quick-a-shan" by locals) a 2.5 mi (4km) river which flows through the city before draining into the bay. Quequechan is a Wampanoag word believed to mean "falling river" or "leaping/falling waters." During the 1960s, Interstate 195 was constructed through the city along the length of the Quequechan River. The portion west of Plymouth Avenue was routed underground through a series of box culverts, while much of the eastern section "mill pond" was filled in for the highway embankment.

In 1653, Freetown was settled at Assonet Bay by members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony as part of Freeman's Purchase, which included the northern part of what is now Fall River. In 1683, Freetown was incorporated as a town within the colony. The southern part of what is now Fall River was incorporated as the town of Tiverton as part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1694, a few years after the merger with Plymouth Colony. In 1746, in the settlement of a colonial boundary dispute between Rhode Island and Massachusetts, Tiverton was annexed to Rhode Island, along with Little Compton and what is now Newport County, Rhode Island. The boundary was then placed approximately at what is now Columbia Street.

In 1703, Benjamin Church, a hero of King Philip's War established a saw mill, grist mill, and a fulling mill on the Quequechan River. In 1714, Church sold his land, along with the water rights to Richard Borden of Tiverton and his brother Joseph. This transaction would prove to be extremely valuable 100 years later, helping to establish the Borden family as the leaders in the development of Fall River's textile industry.

During the 18th century, the area consisted mostly of small farms and relatively few inhabitants. In 1778, the Battle of Freetown, was fought here during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) after British raids badly damaged Bristol and Warren. The militia of Fall River, at that time known as Freetown, put up a stronger defense against a British force.

In 1803, Fall River was separated from Freetown and officially incorporated as its own town. A year later, Fall River changed its name to "Troy." The name "Troy" was used for 30 years and was officially changed back to Fall River on February 12, 1834. During this period, Fall River was governed by a three-member Board of Selectmen, until it became a City in 1854.

In 1835, The Fall River Female Anti Slavery Society was formed (one of the many anti-slavery societies in New England) to promote abolition and to allow a women's space to conduct social activism. There was an initial group, which was wary of allowing free black full membership, so a second group (this one) was formed in response by Elizabeth Buffum Chace and her sisters, who were committed to allowing free black women membership.[7] Sarah G. Buffman, a delegate from the group, was sent to the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in Philadelphia in 1838. Buffman signed all three of the statements that the convention's delegates agreed on.[8]

In July 1843, the first great fire in Fall River's history destroyed much of the town center, including the Atheneum, which housed the Skeleton in Armor which had been discovered in a sand bank in 1832 near what is now the corner of Hartwell and Fifth Street.

During this time, the southern part of what is now Fall River (south of Columbia Street) remained part of Tiverton, Rhode Island. In 1856, the town of Tiverton, Rhode Island voted to split off its industrial northern section as Fall River, Rhode Island. In 1861, after decades of dispute, the United States Supreme Court moved the state boundary to what is now State Avenue, unifying both Fall Rivers as a city in Massachusetts (among other changes; see History of Massachusetts § Rhode Island eastern border).

Industrial development and prosperity

[edit]

19th century

[edit]The early establishment of the textile industry in Fall River grew out of the developments made in nearby Rhode Island, beginning with Samuel Slater at Pawtucket, Rhode Island in 1793. In 1811, Col. Joseph Durfee, the Revolutionary War veteran and hero of the Battle of Freetown in 1778, built the Globe Manufactory, a spinning mill at the outlet of Cook Pond on Dwelly St. near what is now Globe Four Corners in the city's South End. (It was part of Tiverton, Rhode Island at the time.) While Durfee's mill itself was not particularly successful, its establishment marked the beginning of Fall River's time as a mill city.

The real development of Fall River's industry, however, would occur along the falling river from which it was named, about a mile north of Durfee's first mill. The Quequechan River, with its eight falls, combined to make Fall River the best tidewater privilege in southern New England. It was perfect for industrialization—big enough for profit and expansion, yet small enough to be developed by local capital without interference from Boston.[9]

The Fall River Manufactory was established by David Anthony and others in 1813. That same year, the Troy Cotton & Woolen Manufactory was founded by a group of investors led by Oliver Chace of Swansea. Chace had worked as a carpenter for Samuel Slater in his early years. The Troy Mill opened in 1814 at the upper end of the falls.

In 1821, Colonel Richard Borden (along with Maj. Bradford Durfee) established the Fall River Iron Works at the lower part of the Quequechan River. Durfee was a shipwright, and Borden was the owner of a grist mill. After an uncertain start, in which some early investors pulled out, the Fall River Iron Works was incorporated in 1825. The Iron Works began producing nails, bar stock, and other items, such as bands for casks in the nearby New Bedford whaling industry. They soon gained a reputation for producing nails of high quality, and business flourished. In 1827, Col. Borden began regular steamship service to Providence, Rhode Island.[10]

The American Print Works was established in 1835 by Holder Borden, uncle of Col. Richard Borden. With the leadership of the Borden family, the American Print Works (later known as the American Printing Company) became the largest and most important textile company in the city, employing thousands at its peak in the early 20th century. Richard Borden also constructed the Metacomet Mill in 1847, which today is the oldest remaining textile mill in the city; it is located on Anawan Street.

By 1845, the Quequechan's power had been all but maximized. The Massasoit Steam Mill was established in 1846, above the dam near the end of Pleasant Street. However, it would be another decade or so when improvements in the steam engine by George Corliss would enable the construction of the first large steam-powered mill in the city, the Union Mills in 1859.

The advantage of being able to import bales of cotton and coal to fuel the steam engines to Fall River's deep water harbor (and ship them out from the same) made Fall River the city of choice for a series of cotton mill magnates. The first railroad line serving Fall River, The Fall River Branch Railroad, was incorporated in 1844 and opened in 1845. In 1847, the first regular steamboat service to New York City began. The Fall River Line, as it came to be known, operated until 1937, and for many years was the preferred way to travel between Boston and Manhattan. The Old Colony Railroad and Fall River Railroad merged in 1854, forming the Old Colony and Fall River Railroad.

In 1854, Fall River was officially incorporated as a city; it had a population of about 12,000.[11] Its first mayor was James Buffington.

Fall River profited well from the American Civil War and was in a fine position to take advantage of the prosperity that followed. By 1868, it had surpassed Lowell as the leading textile city in America with over 500,000 spindles.

Expansion and growth

[edit]

In 1871 and 1872, a "most dramatic expansion" of the city occurred: 15 new corporations were founded, building 22 new mills throughout the city, while some of the older mills expanded. The city's population increased by 20,000 people during these two years, while overall mill capacity doubled to more than 1,000,000 spindles.

By 1876, the city had one-sixth of all New England cotton capacity and one-half of all print cloth production. The Spindle City, as it became known, was second in the world to only Manchester, England in terms of output.

To house the thousands of new workers—mostly Irish and French Canadian immigrants during these years—over 12,000 units of company housing were built. Unlike the well-spaced boardinghouses and tidy cottages of Rhode Island, worker housing in Fall River consisted of thousands of wood-framed, multi-family tenements, usually three-floor "triple-deckers" with up to six apartments. Many more privately owned tenements supplemented the company housing.[12]

During the 19th century, Fall River became famous for the granite rock on which much of the city is built. Several granite quarries operated during this time, the largest of which was the Beattie Granite Quarry, near what is now the corner of North Quarry and Locust Streets.[13] Many of the mills in the city were built from this stone, and it was highly regarded as a building material for many public buildings and private homes alike. The Chateau-sur-Mer mansion in Newport, Rhode Island was constructed from Fall River granite, known for its greyish-pink color.

While most of the mills "above the hill" were constructed from native Fall River granite, nearly all of their counterparts along the Taunton River and Mount Hope Bay were made of red brick due to the high costs and impracticality associated with transporting the rock through the city and down the hill. (One notable exception is the Sagamore Mills on North Main Street, which were constructed from similar rock quarried in Freetown and brought to the site by rail).

20th century

[edit]

Fall River rode a wave of economic prosperity well into the early 20th century. During this time, the city boasted a bustling downtown with several upscale hotels and theaters. As the city continuously expanded during the late 19th century, additional infrastructure such as parks, schools, streetcar lines, a public water supply, and sewerage system were constructed to meet the needs of its growing population.

From 1896 to 1912, Fall River was the headquarters of the E. P. Charlton & Company, a chain of five and ten cent stores. Founded at Fall River in 1890 by Seymour H. Knox and Earle Perry Charlton as the Knox & Charlton Five and Ten Cent Store, E.P. Charlton operated fifty-eight stores in the United States and Canada by the time of its merger with several other retailers to form the F. W. Woolworth Company in 1912.

In 1920, the population of Fall River peaked at 120,485.[14]

-

North Main Street, c. 1910

-

First Cotton Mill, built in 1811

-

Printing Works, c. 1920

-

The Charlton Block, 1908

The cotton mills of Fall River had built their business largely on one product: print cloth. Around 1910, the city's largest employer, the American Printing Company (APC), employed 6,000 people and was the largest company printer of cloth in the world. Dozens of other city mills solely produced cloth to be printed at the APC.

World War I had provided a general increase in demand for textiles, and many of the mills of New England benefited during this time. The post-war economy quickly slowed, however, and production quickly outpaced demand. The Northern mills faced serious competition from their Southern counterparts due to lower labor and transportation costs, as well as the South's large investment in new machinery and other equipment. In 1923, Fall River faced the first wave of mill closures. Several of the mills merged, allowing them to remain in business into the late 1920s.

The worst fire in Fall River's history occurred on the evening of February 2, 1928.[15] It began when workers were dismantling the recently vacated Pocasset Mill. During the night, the fire spread quickly and wiped out a large portion of downtown. City Hall was spared, but was badly damaged. Today, many of the structures near the corner of North Main and Bedford Street date from the early 1930s, as they were rebuilt soon after the fire.

By the 1930s and the Great Depression, many of the mills were out of business and the city was bankrupt. The once mighty American Printing Company finally closed for good in 1934. In 1937, their huge plant waterfront on Water Street was acquired by the Firestone Tire & Rubber Company and soon employed 2,600 people. A handful managed to survive through World War II and into the 1950s. In October 1941, just a few weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, another large fire broke out in the main building of the printworks. The fire was a major setback to the U.S. war effort; 30,000 pounds (13,607 kilograms) of raw rubber worth $15 million was lost in the inferno.[16]

With the demise of the textile industry, many of the city's mills were occupied by smaller companies, some in the garment industry, traditionally based in the New York City area but attracted to New England by the lure of cheap factory space and an eager workforce in need of jobs.[17] The garment industry survived in the city well into the 1990s, by which point it had fallen victim to globalization and foreign competition.[18]

Modern era

[edit]

In the 1960s, the city's landscape was drastically transformed with the construction of the Braga Bridge and Interstate 195, which cut directly through the heart of the city. In the wake of the highway building boom, the city lost many of its longtime landmarks. The Quequechan River was filled in and re-routed for much of its length. The historic falls were diverted into underground culverts. A series of elevated steel viaducts was constructed to allow access the new bridge. Many historic buildings were demolished, including the Old City Hall, the Troy Mills, the Second Granite Block (built after the 1928 fire), as well as other 19th-century brick-and-mortar buildings near Old City Hall.

Constructed directly over Interstate 195 in the place of it predecessor, the new city hall (known as Government Center) was opened in 1976 after years of construction delays and quality control problems. Built in the Brutalist style popular in the 1960s and 1970s, the new city hall drew complaints from city workers and residents almost immediately.[citation needed]

In 1970, Valle's Steak House opened one of its landmark restaurants on William S. Canning Boulevard in the city's South End. The steak house was popular with Fall River residents, but economic challenges caused the chain to close all of its restaurants in the 1980s.[19]

Also during the 1970s, several modern apartment high-rise towers were built throughout the city, many part of the Fall River Housing Authority. There were two built near Milliken Boulevard, two on Pleasant Street in Flint Village, another on South Main Street, and in the north end off Robeson Street. Today, these high-rises mostly house the elderly.

In 1978, the city opened the new B.M.C. Durfee High School in the North End, replacing the historic Rock Street building that had become overcrowded and outdated for use as a high school. The "new" Durfee is one of the largest high schools in Massachusetts.

Since approximately 1980, there has been a considerable amount of new development in the North End of the city. A significant number of new single- and multi-family housing developments have been constructed, particularly along North Main Street.

In 2017, Fall River was ranked the 51st most dangerous city in the United States. It was also the third most dangerous city in Massachusetts and fourth most dangerous city in New England.[20]

On January 20, 2019, a cannabis dispensary opened in Fall River, becoming only the sixth dispensary in Massachusetts and the first in Southeastern Massachusetts to open to anyone 21 years or older.[21]

Geography

[edit]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 40.2 square miles (104.2 km2), of which 33.1 square miles (85.8 km2) is land and 7.1 square miles (18.4 km2), or 17.68%, is water.[22]

Water power from the Quequechan River and natural granite helped form and shape Fall River into the city it is today. The Quequechan River once flowed through downtown unrestricted, providing water power for the mills and, in the last 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) of its length, down a series of eight steep waterfalls falling 128 feet (39 m) into the Taunton River at the head of the deep Mount Hope Bay. Fall River and surrounding areas are located in the northeastern coastal forests, which make up the temperate broadleaf and mixed forest biome.

Fall River was the only city on the East Coast of the United States to have had an exposed waterfall in part of its downtown area; it flowed less than 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) into a sheltered harbor at the edge of downtown. Fall River has two large lakes (originally one lake) and a large portion of protected woodlands on the eastern part of the city, which is higher in elevation, with the Quequechan River draining out of the ponds and flowing 2.5 miles (4.0 km) through the heart of the city, emptying out an estimated 26 million US gallons (98×106 L) per day into the deep Mount Hope Bay/Taunton River estuary in the western part of the city.

The city lies on the eastern border of Mount Hope Bay, which begins at the mouth of the Taunton River starting south from the Charles M. Braga Jr. Memorial Bridge. The greater portion of the city is built on hillsides rising quite abruptly from the water's edge to a height of more than 200 feet (60 m). From the summits of these hills, the terrain extends back in a comparatively level table-land, on which a large section of the city now stands.

Two miles (3 km) eastward from the shore lies a chain of deep and narrow ponds, eight miles (13 km) long, with an average width of three-quarters of a mile, and covering an area of 3,500 acres (14 km2). These ponds are supplied by springs and brooks, draining a watershed of 20,000 acres (81 km2). The northern pond is the North Watuppa Pond, the city's main reservoir. The southern pond is the South Watuppa Pond. The narrow strip of land where the two ponds meet is known as The Narrows. East of the North Watuppa Pond is the Watuppa Reservation, which includes several thousand acres of forest-land for water supply protection that extends north into the Freetown-Fall River State Forest, and east to the Copicut Reservoir. Copicut Pond is located on the border of Dartmouth in North Dartmouth's Hixville section that borders Fall River. Copicut Hill, the highest point in Fall River, is located between North Watuppa Pond and the Copicut Reservoir. The hill has a summit elevation of greater than 404 feet (123 m) above sea level.[23]

The Quequechan River breaks out of its bed in the west part of the South Watuppa Pond, just west of The Narrows, and flows through the city (partially underground in conduits) where it falls to a channel leading to what is now Fall River Heritage State Park at Battleship Cove on the Taunton River. The Quequechan River originally flowed unconfined over an almost level course for more than a mile. In the last half-mile (800 m) of its progress it rushes down the hillside in a narrow, precipitous, rocky channel, creating the falls for which Fall River is named. In this distance the total fall is about 132 feet (40 m). and the volume of water 122 cubic feet (3.5 m3) per second.

Originally an attractive feature of the landscape, the Quequechan has seldom been visible since it was covered over by cotton mills and the Bay Colony Railroad line in the 19th century. As the Quequechan became an underground feature of the industrial landscape, it also became a sewer. In the 20th century the mills were abandoned and some of them burned, exposing the falls once more. Because of highway construction in the 1960s, the waterfalls were buried under Interstate 195, which crosses the Taunton River at Battleship Cove. Plans exist to "daylight" the falls, restore or re-create them, and build a green belt with a bicycle path along the Quequechan River.

In the south end, Cook Pond, also formerly known as Laurel Lake, is located east of the Taunton River and west of the South Watuppa Pond. The area between the modern day Cook and South Watuppa Ponds, east of the Taunton River and north of Tiverton, Rhode Island, was once referred to as "Pocasset Swamp" during King Philip's War in 1675–1676.

Fall River is a part of the South Coast region of Massachusetts.

Neighborhoods

[edit]The city is divided into two by Interstate 195, which runs directly through downtown and underneath Fall River City Hall. The two sections of the city contain a number of distinct neighborhoods.

Northern Neighborhoods ("The North End"; North of I-195, extending to the city's northern border with Freetown, Massachusetts and western border with Dartmouth, Massachusetts)

- Waterfront/Battleship Cove (east of Route 79 to the edge of the Taunton River/Mount Hope Bay)

- The Highlands

- Lower Highlands (Bedford St, up High St to Prospect St)

- Upper Highlands (Prospect St along President Ave, up to Wilson Rd)

- Fall River Industrial Park ("Airport Road", area north of Wilson Rd bounded to the west by Route 24 and to the east by Riggenbach Rd)

- Fall River/Freetown State Forest

Southern Neighborhoods ("The South End"; South of I-195, extending to the city's southern border with Tiverton, RI)

- Flint Village ("The Flint")South and east of Bedford and Quarry Sts, respectively)

- Globe Village (Cook Pond, Broadway)

- Townsend Hill (South Main and Bay St Neighborhoods bordering Tiverton, R.I.)

- Maplewood

Parks

[edit]Fall River has 23 municipal parks and playgrounds, including three designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.[24][25] Fall River's more notable parks include:

- Kennedy Park (Olmsted, 1868): South Main Street, 54 acres, four tennis courts, three baseball fields, two basketball courts, softball field, skating pond, playground[24]

- North Park (Olmsted, 1901): President Avenue, 25 acres, two baseball fields, two basketball courts, playground, skating pond, skate park[24]

- Ruggles Park (Olmsted, 1903): Locust Street, 9 acres, basketball court, playground, softball field[24]

- Bicentennial Park: Davol Street, 2 acres, boat ramp[24]

- Lafayette Park: Eastern Avenue, 11 acres, baseball field, basketball court, playground, swimming pool, tennis court, skate park[24]

- Quequechan River Rail Trail: 2.5 mile Bike path from Britland Park and Rodman Street to Westport Line on Route 6[26]

The city is also home to several Massachusetts state parks, including Fall River Heritage State Park and Freetown-Fall River State Forest.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 1,296 | — |

| 1820 | 1,594 | +23.0% |

| 1830 | 4,158 | +160.9% |

| 1840 | 6,738 | +62.0% |

| 1850 | 11,524 | +71.0% |

| 1860 | 14,026 | +21.7% |

| 1870 | 26,766 | +90.8% |

| 1880 | 48,961 | +82.9% |

| 1890 | 74,398 | +52.0% |

| 1900 | 104,863 | +40.9% |

| 1910 | 119,295 | +13.8% |

| 1920 | 120,485 | +1.0% |

| 1930 | 115,274 | −4.3% |

| 1940 | 115,428 | +0.1% |

| 1950 | 111,963 | −3.0% |

| 1960 | 99,942 | −10.7% |

| 1970 | 96,898 | −3.0% |

| 1980 | 92,574 | −4.5% |

| 1990 | 92,703 | +0.1% |

| 2000 | 91,938 | −0.8% |

| 2010 | 88,857 | −3.4% |

| 2020 | 94,000 | +5.8% |

| 2022* | 93,682 | −0.3% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[39] | ||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[40] | Pop 2010[41] | Pop 2020[42] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 82,274 | 74,107 | 66,746 | 89.49% | 83.40% | 71.01% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 2,097 | 3,016 | 4,643 | 2.28% | 3.39% | 4.94% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 147 | 163 | 185 | 0.16% | 0.18% | 0.20% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,980 | 2,249 | 2,475 | 2.15% | 2.53% | 2.63% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 16 | 10 | 17 | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.02% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 323 | 787 | 1,370 | 0.35% | 0.89% | 1.46% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 2,061 | 1,963 | 5,982 | 2.24% | 2.21% | 6.36% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3,040 | 6,562 | 12,582 | 3.31% | 7.38% | 13.39% |

| Total | 91,938 | 88,857 | 94,000 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

According to the U.S. Census of 2020, the population of Fall River is 94,000. The largest racial groups within the city were 87.2% (83.4% Non-Hispanic) White, 3.5% African American, 2.5% Asian and 0.2% Native American and 7.4% Hispanic or Latino. 49% of residents are Luso American or have origins somewhere in the former Portuguese Empire. 37% of the population described themselves as being of Portuguese ancestry. The next largest groups by ancestry are French (12.4%) the original immigrants to largely populate Fall River until the Portuguese started immigrating to the area, Irish (8.9%), Cape Verdean (8.1%), English (6.0%), French Canadian (5.9%), Puerto Rican (4.5%), and Italian (3.6%).[43]

Fall River and its surrounding communities form much of the Massachusetts portion of the Providence metropolitan area, which has an estimated population of 1,622,520.

In percentage terms, Fall River has the largest Portuguese American population in the United States. The exact percentage of the population they make up is disputed; a 2005 study by the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth estimated that 49.6% of city residents are Portuguese American,[44] while other sources estimate that 43.9% are.[45]

The city has 38,759 households and 23,558 families. The population density was 2,963.7 inhabitants per square mile (1,144.3/km2). There were 41,857 housing units at an average density of 1,349.3 per square mile (521.0/km2). Of the 38,759 households, 29.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.3% were married couples living together, 16.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.2% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.32 and the average family size was 3.00.

In terms of age, the population was spread out, with 24.1% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 20.0% from 45 to 64, and 16.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.9 males.

The median household income was $29,014, and the median family income was $37,671. Males had a median income of $31,330 versus $22,883 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,118. About 14.0% of families and 17.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.4% of those under age 18 and 17.4% of those age 65 or over.[43]

Income

[edit]Fall River is ranked 344th out of Massachusetts' 350 municipalities in terms of per capita income.[46][47][48]

| Rank | ZIP Code (ZCTA) | Per capita income |

Median household income |

Median family income |

Population | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | $35,763 | $66,866 | $84,900 | 6,605,058 | 2,530,147 | |

| Bristol County | $28,837 | $55,298 | $72,018 | 549,870 | 210,037 | |

| United States | $28,155 | $53,046 | $64,719 | 311,536,594 | 115,610,216 | |

| 1 | 02720 | $25,090 | $41,910 | $56,091 | 30,811 | 13,079 |

| Fall River | $21,257 | $33,211 | $42,962 | 88,811 | 38,258 | |

| 2 | 02721 | $19,321 | $30,180 | $38,133 | 26,141 | 10,943 |

| 3 | 02723 | $18,980 | $28,120 | $34,835 | 14,298 | 6,442 |

| 4 | 02724 | $18,827 | $27,390 | $39,246 | 16,769 | 7,561 |

Culture

[edit]

Fall River retains a vibrant mix of cultures that date back to its time as an immigration hub. While the distinct ethnic neighborhoods formed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries have changed over the years, the legacy of immigrants who came to work in the mills can be found in the various parishes and restaurants throughout the city. This heritage is commemorated by the 19 flags which make up the "Banners of Allegiance" at Gromada Plaza.[49] Erected in 1979 across from City Hall (and restored in 2019), this landmark commemorates the diverse nationalities of Fall River's residents.[49]

The city is host to several ethnic festivals throughout the year. The largest, the Great Feast of the Holy Ghost, occurs each August at Kennedy Park and attracts "more than 100,000 visitors."[50] The feast is held over a total of four days and includes parades, music, food, and a crowning ceremony and procession featuring local dignitaries and guests from Portugal, Brazil, and the Azores.[51][50]

Each summer, the city uses its waterfront at Heritage State Park and Battleship Cove for a Fourth of July fireworks display. For many years, the waterfront also hosted the annual Fall River Celebrates America Festival, sponsored by the Fall River Chamber of Commerce. The event was suspended in 2010 due to lack of financial support stemming from the Great Recession. While the Chamber of Commerce hoped to hold the event again in 2011, it has not been held since.[52]

Performing arts

[edit]A number of community organizations have made concerted efforts to promote the arts in the city, using vacant mill space for studios and performance centers. The Narrows Center for the Arts, located on Anawan Street, has been played by a number of national and international acts since its opening in 2001, including Rosanne Cash, Los Lobos, Blue Öyster Cult, Dr. John, The Avett Brothers, Richie Havens, Lake Street Dive and Susan Tedeschi.[53] A proposal is in place to revitalize the downtown area by the creation of an Arts District. Along with the art centers being established throughout the city, Fall River has numerous Portuguese/Community Bands throughout the city that perform throughout the year.

Visual arts

[edit]In 2020, artists and Fall River natives Harry Gould Harvey IV and Brittni Ann Harvey opened the Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art (Fall River MoCA) in the first floor of a former mill on Bedford Street.[54] The museum aims to "create culturally relevant programming that is in dialog with the global contemporary art world."[55]

Religion

[edit]Fall River remains a predominantly Roman Catholic city due to the French Canadians who first populated the city, and is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Fall River. St. Mary's Cathedral was formed in the 1850s by Irish immigrants; Edgar DaCunha has served as bishop since 2014. Santo Christo Parish on Columbia Street is known as the Mother Church of the Portuguese parishes in the diocese. The Church was established in 1892 to serve the local Portuguese community, Many of whom came from the Azorean island of São Miguel. Other notable Catholic churches include St. Anne's Church, Good Shepherd Church (formerly Saint Patrick's), and the former Notre Dame de Lourdes in the Flint neighborhood, which was destroyed in a large fire on May 10, 1982. At the time of the city's peak population in 1920, there were over two dozen Catholic parishes existing throughout the city, with each ethnic enclave having its own parish. In recent years, the diocese has merged several parishes in the city, closing some and renaming the united congregations, bringing the total number of parishes in the diocese to ten as of 2021.[56] St. Louis the King Church closed in 2000.[57]

Historically, the Highlands neighborhood was predominantly Protestant, with several churches in the area of North Main and Rock Streets, notably including the Central Congregational Church and the First Congregational Church, known for hosting many New England luminaries before its demise in a fire in the 1980s.

German Jewish settlers arrived in Fall River beginning in the 1860s and continuing into the 1870s.[58] The 1880s and 1890s saw the arrival of Russian Jewish immigrants.[58] At the start of the 20th century, Fall River was home to three synagogues.[58] The Jewish community historically worked in peddling, retail, and clothing stores.[58] Temple Beth-El was founded in 1924 on High Street.[58] In 1970 there were three congregations serving 4,000 Jews in Fall River; by 2008 that number had declined to less than 1,000.[58]

Various other ethno-religious groups also live in the city. Recent arrivals from Cambodia and India maintain temples in the city, such as Wat Udomsaharatanaram and BAPS Shri Swaminarayanwasi.

Government

[edit]City government and services

[edit]The city is led by the mayor-council form of government. There is a mayor and nine at-large city councillors, elected in odd-years to two year terms. The mayor, along with their appointed city administrator, lead and manage the city's day-to-day operations. The majority of the city's municipal offices are located at Government Center.

The city's police department is consolidated into a large central police station. There are six fire stations located around the city. The Fire Headquarters is located on Commerce Drive, across from the former Fall River Municipal Airport.

There are four post offices in the city. The central, located adjacent to Government Center, is modeled after the James Farley Post Office in New York City. The central branch was named after the late Sgt. Robert Barrett in May 2011, a Fall River native who died in Afghanistan in 2010. Additional branches are located in the Flint, the South End, and the Highlands.

The city is home to several state and county-level courthouses. The murder trial of former New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez in 2015 was held at the district courthouse on South Main Street.[59]

State and federal representation

[edit]Fall River is represented by three separate Massachusetts House of Representatives districts; only one, the 7th Bristol, is wholly within city limits. As of 2021, the city is represented by Democrats Carole Fiola (6th Bristol), Alan Silvia (7th Bristol), and Paul A. Schmid III (8th Bristol). The city is entirely within the First Bristol and Plymouth district, represented by State Senator Michael Rodrigues (D-Fall River). The First Bristol and Plymouth also includes the towns of Freetown, Lakeville, Rochester, Somerset and Swansea.[60][61]

Fall River's state highways are patrolled by the Third Barracks of Troop D of the Massachusetts State Police, based out of Dartmouth.

On the national level, the city is divided between two congressional districts. Massachusetts' 4th congressional district, represented by Democrat Jake Auchincloss, contains most of the city, while Massachusetts' 9th congressional district, represented by Democrat Bill Keating, contains a part of the northeastern portion of the city.

Fall River's voting history largely mirrors that of Massachusetts as a whole. Before 1928, Fall River was a Republican-leaning city. Beginning in 1928, Fall River became a strongly Democratic city, owing to the large Catholic population in the city. Fall River even voted Democratic in the Republican landslide election wins in 1952 and 1956. In 2024, Donald Trump became the first Republican since Calvin Coolidge to win the city, winning the city 51%-47%.

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of February 1, 2019[62] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 20,658 | 44.10% | |||

| Republican | 3,880 | 8.28% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 21,353 | 45.59% | |||

| Libertarian | 951 | 2.03% | |||

| Total | 46,842 | 100% | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 50.5% 14,843 | 47.6% 13,981 | 1.9% 459 |

| 2020 | 43.0% 13,571 | 55.3% 17,459 | 1.7% 535 |

| 2016 | 36.2% 10,850 | 58.2% 17,467 | 4.8% 1,444 |

| 2012 | 24.8% 7,390 | 73.5% 21,878 | 1.4% 427 |

| 2008 | 25.4% 7,933 | 72.4% 22,591 | 2.2% 678 |

| 2004 | 23.3% 7,369 | 75.6% 23,859 | 1.1% 332 |

| 2000 | 19.4% 5,621 | 76.0% 22,051 | 4.6% 1,343 |

| 1996 | 14.3% 4,290 | 76.2% 22,805 | 9.5% 2,831 |

| 1992 | 17.5% 5,456 | 59.8% 18,652 | 22.8% 7,102 |

| 1988 | 29.2% 8,394 | 70.1% 20,184 | 0.8% 216 |

| 1984 | 35.5% 11,463 | 64.2% 20,722 | 0.3% 109 |

| 1980 | 29.6% 9,958 | 58.5% 19,644 | 11.9% 4,001 |

| 1976 | 27.1% 10,065 | 70.5% 26,126 | 2.4% 886 |

| 1972 | 36.4% 14,088 | 63.0% 24,379 | 0.6% 216 |

| 1968 | 18.0% 7,449 | 78.8% 32,516 | 3.2% 1,324 |

| 1964 | 11.2% 5,096 | 88.6% 40,502 | 0.2% 101 |

| 1960 | 20.4% 10,055 | 79.4% 39,036 | 0.2% 100 |

| 1956 | 48.1% 24,575 | 51.8% 26,469 | 0.1% 83 |

| 1952 | 41.5% 22,791 | 58.3% 32,060 | 0.2% 133 |

| 1948 | 26.3% 13,915 | 72.4% 38,347 | 1.3% 668 |

| 1944 | 30.6% 13,835 | 69.2% 31,249 | 0.2% 104 |

| 1940 | 29.1% 13,766 | 70.5% 33,355 | 0.4% 201 |

| 1936 | 26.2% 11,181 | 67.6% 28,813 | 6.2% 2,646 |

| 1932 | 35.0% 12,493 | 63.4% 22,642 | 1.7% 596 |

| 1928 | 34.8% 13,012 | 64.1% 23,965 | 1.1% 401 |

| 1924 | 56.6% 17,190 | 32.7% 9,935 | 10.7% 3,232 |

| 1920 | 64.4% 15,943 | 33.0% 8,166 | 2.6% 655 |

| 1916 | 48.1% 6,619 | 50.1% 6,894 | 1.8% 253 |

| 1912 | 31.5% 4,047 | 39.8% 5,125 | 28.7% 3,688 |

| 1908 | 51.7% 6,207 | 41.5% 4,985 | 6.8% 820 |

| 1904 | 49.5% 5,691 | 46.8% 5,382 | 3.7% 426 |

| 1900 | 57.6% 6,516 | 39.6% 4,481 | 2.8% 320 |

| 1896 | 65.7% 6,925 | 31.9% 3,366 | 2.4% 251 |

| 1892 | 51.3% 4,812 | 47.5% 4,451 | 1.2% 109 |

| 1888 | 50.6% 4,125 | 48.4% 3,952 | 1.0% 81 |

| 1884 | 54.5% 3,204 | 38.2% 2,244 | 7.3% 428 |

| 1880 | 57.6% 3,325 | 39.8% 2,299 | 2.6% 149 |

| 1876 | 60.2% 2,533 | 39.8% 1,672 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1872 | 71.5% 2,100 | 28.5% 839 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1868 | 72.3% 1,814 | 27.7% 694 | 0.0% 0 |

Education

[edit]

Public schools

[edit]Fall River Public Schools operates all public schools in the city. Fall River has one public high school, B.M.C. Durfee High School. Durfee alum include Chris Herren, former NBA player for the Denver Nuggets and the Boston Celtics, former Supreme Court Justice James M. McGuire, and Humberto Sousa Medeiros, a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and former Archbishop of Boston.

The city is also home to Diman Regional Vocational Technical High School, which serves Fall River and the towns of Somerset, Swansea, and Westport. Chef Emeril Lagasse is a Diman Graduate. The school dates back to the Durfee Textile School, which branched out to include Diman. (The college, founded to promote the city's textile sciences, is now a part of University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.)

Private schools

[edit]In addition to public schools, there are several private and parochial schools in the city, including six Catholic schools, two private schools, a Christian academy (East Gate Christian Academy). Atlantis Charter School, a Pre-K through 8 charter school with a marine science-themed curriculum, was founded in 1995.[64] The city was also home to Bishop Connolly High School, a Catholic high school named for Bishop James Louis Connolly, fourth Bishop of the Diocese of Fall River, however, it closed its doors in May 2023. Bishop Feehan was located in Fall River from 1961 to 1972.[65]

Espirito Santo School opened on September 19, 1910, and was the first Portuguese grammar school to open in the United States. As of 2011, the majority of its students were ethnic Portuguese, and 70% of the students were bilingual.[66]

Higher education

[edit]University of Massachusetts Dartmouth has two branches in the city: the Professional and Continuing Education Center, located at 139 South Main Street, and the Advanced Technical & Manufacturing Center at the Narrows, on the former site of the Kerr Mills. Bristol Community College, founded in 1965, is a two-year college offering associate degrees as well transfer programs to four-year institutions. Eastern Nazarene College offers Adult Studies/LEAD classes in Fall River as well. It has GED programs and a recording studio.[67]

Sister cities

[edit]Fall River is twinned with:

Ponta Delgada, The Azores – Portugal

Ponta Delgada, The Azores – Portugal

Library

[edit]

Fall River established its public library in 1860.[68][69] As of fiscal year 2022, the city of Fall River spends 0.53% ($1,861,112) of its budget on its public library—roughly $20 per person.[70]

The main location of the Fall River Public Library is located at 104 North Main Street, within the Downtown Fall River Historic District. It opened in 1899, and was designed by architect Ralph Adams Cram in the Renaissance Revival style. It is constructed from native Fall River granite. The building underwent an extensive renovation during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The public library system also includes two branches; the South End Branch, located at 58 Arch Street, and the East End Branch, located at 1386 Pleasant Street.[71]

The Fall River Historical Society also maintains the Charlton Library of Fall River History.[72]

Transportation

[edit]

Fall River has historically been a transportation hub for the South Coast and Mount Hope Bay areas due to its location along the Taunton River. In addition to the Fall River Line, Slade's Ferry ran from Fall River to Somerset beginning in the 17th century. In 1875, Slade's Ferry Bridge was opened, connecting the two cities by trolley (and late by car). A two-tiered steel swing-span bridge, Slade's Ferry Bridge extended over 1,100 feet (340 m) from Remington Avenue in Fall River to the intersection of Wilbur Avenue, Riverside Avenue and Brayton Avenue in Somerset. The bridge was in use until 1970, when it was closed and subsequently demolished. The path of the bridge is now roughly marked by twin sets of power lines crossing the river.

In 1903, the state authorized construction of a second bridge, the Brightman Street Bridge, a four lane, 922-foot (281 m) long drawbridge ending at its namesake street; the bridge opened in 1908. Closed in 2011 and inaccessible to pedestrians and vehicles, the old span is still partially standing. By the 1980s, structural issues with the Brightman Street Bridge resulted in frequent closures for repair, straining local traffic and forcing motorists to take long detours. By 1983, plans were being made to build a new bridge 1,500 feet (460 m) north of the original, which would directly link with Route 138 in Somerset. Plans were put on hold in 1989 due to Coast Guard concerns. Construction of the new span began in the late 1990s and continued until late 2011. The new bridge, the Veterans Memorial Bridge, was formally dedicated on September 11, 2011.

Construction on the Charles M. Braga Jr. Memorial Bridge began in 1959, and the bridge opened to traffic in the spring of 1966. The six-lane cantilever truss highway bridge spans 1.2 miles (1.9 km) and was constructed in tandem with Interstate 195. The bridge is named for Charles M. Braga Jr., who died during the attack on Pearl Harbor while aboard the U.S.S. Pennsylvania.[73]

Road

[edit]Interstate 195 is the main east–west artery through the city for motorists. The highway enters Fall River from Somerset via the Charles M. Braga Jr. Memorial Bridge, continuing through the center of the city to The Narrows and eastwards into Westport. I-195 connects Fall River to New Bedford and Cape Cod to the east and Providence to the west. The highway roughly parallels both the Bay Colony/New Bedford Cape Cod Railroad as well the original path of the Quequechan River. In 1999, a cement ceiling tile fell from the roof of the tunnel beneath Government Center, landing on several cars and causing minor injuries.[74]

In addition to I-195, Fall River is served by six other routes, being U.S. 6, MA 138, MA 79, MA 81, MA 177, and MA 24.

U.S 6 - This route enters the city from Somerset via an overlap with MA 138 crossing the Taunton River on the Veterans Memorial Bridge. After crossing the river, it intersects with MA 79 (W. Fall River Expy.) and parallels the highway for a few blocks. At President Ave. it turns east, splitting from MA 138 and following the avenue until it reaches a circle with Eastern Ave and Exit 5 of MA 24. It then turns southwards onto Eastern Ave, which it follows until US 6 reaches Maritime St, where it turns back east, paralleling I-195 in the Narrows until it reaches Westport.

U.S 6 - This route enters the city from Somerset via an overlap with MA 138 crossing the Taunton River on the Veterans Memorial Bridge. After crossing the river, it intersects with MA 79 (W. Fall River Expy.) and parallels the highway for a few blocks. At President Ave. it turns east, splitting from MA 138 and following the avenue until it reaches a circle with Eastern Ave and Exit 5 of MA 24. It then turns southwards onto Eastern Ave, which it follows until US 6 reaches Maritime St, where it turns back east, paralleling I-195 in the Narrows until it reaches Westport. MA 24 (Fall River Expressway) - This highway enters Fall River from Tiverton. (as RI 24) A few exits are contained in the city, including one for MA 81, a brief overlap with I-195, and an interchange with MA 79. It stays in the eastern edge of the city, following the Watuppa Ponds. The highway continues northwards to Freetown, Taunton, and eventually to I-93/MA 128 and Boston.

MA 24 (Fall River Expressway) - This highway enters Fall River from Tiverton. (as RI 24) A few exits are contained in the city, including one for MA 81, a brief overlap with I-195, and an interchange with MA 79. It stays in the eastern edge of the city, following the Watuppa Ponds. The highway continues northwards to Freetown, Taunton, and eventually to I-93/MA 128 and Boston. MA 79 (Western Fall River Expressway) - This road starts at the intersection with I-195 and MA 138 on the western waterfront nearby Battleship Cove. It continues northwards through the western edge of the city by the river, intersecting with US 6 and then goes up to MA 24 in the northern end of the city, continuing its overlap with the highway until Freetown. Large sections of this highway have been torn down in recent years and have been replaced with avenues and at-grade intersections, including a large portion which closed in 2023.

MA 79 (Western Fall River Expressway) - This road starts at the intersection with I-195 and MA 138 on the western waterfront nearby Battleship Cove. It continues northwards through the western edge of the city by the river, intersecting with US 6 and then goes up to MA 24 in the northern end of the city, continuing its overlap with the highway until Freetown. Large sections of this highway have been torn down in recent years and have been replaced with avenues and at-grade intersections, including a large portion which closed in 2023. MA 81 - This route enters the city from Tiverton (RI 81) as well, intersecting with MA 24 not long past the state border. It follows Rhode Island Ave. and Plymouth Ave. until the road intersects with I-195 in downtown Fall River, in which it ends.

MA 81 - This route enters the city from Tiverton (RI 81) as well, intersecting with MA 24 not long past the state border. It follows Rhode Island Ave. and Plymouth Ave. until the road intersects with I-195 in downtown Fall River, in which it ends. MA 138 - This road enters the city as well from Tiverton, following S. Main St. and then Broadway until approaching I-195. It then overlaps with MA 79 before exiting and crossing with US 6 across the Taunton River into Somerset.

MA 138 - This road enters the city as well from Tiverton, following S. Main St. and then Broadway until approaching I-195. It then overlaps with MA 79 before exiting and crossing with US 6 across the Taunton River into Somerset. MA 177 - This road passes 300 feet through the city in the very southeastern edge, coming from Tiverton (RI 177) and quickly entering Westport, continuing to MA 88 and US 6 in Dartmouth.

MA 177 - This road passes 300 feet through the city in the very southeastern edge, coming from Tiverton (RI 177) and quickly entering Westport, continuing to MA 88 and US 6 in Dartmouth.

Rail

[edit]

Fall River last saw passenger rail service in 1958. An under-construction project named South Coast Rail will bring MBTA Commuter Rail service to a currently under-construction station serving the city via a slight rerouting/extension of the existing Middleborough/Lakeville Line as an interim service by 2023. The line is eventually planned to be rerouted via the Stoughton Branch and the former Dighton and Somerset Railroad by 2030. As of 2022, the nearest passenger rail station is Providence, which is served by the MBTA Providence/Stoughton line and Amtrak's Acela Express and Northeast Regional trains.

Bus

[edit]Along with New Bedford, Fall River shares ownership of the Southeastern Regional Transit Authority (SRTA), a bus network that services both cities, as well as Acushnet, Dartmouth, Fairhaven, Freetown, Mattapoisett, Somerset, Swansea, and Westport.[75] The twelve fixed-route bus lines that service Fall River depart from the Louis D. Pettine Transportation Center, which opened in 2013.[76] Service to Providence, Tiverton, and Newport, Rhode Island is offered by the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA).[77]

Intercity bus service to Boston and Hyannis is provided by Peter Pan, with connections available to the company's larger network via transfers.[78]

Air

[edit]Fall River Municipal Airport, opened in 1951, served as a general aviation airport for small planes and commuter flights to the Cape and Islands for several decades. By the 1960s, the airport had fallen into a state of relative disrepair. it was closed on February 18, 1996, after the Federal Aviation Administration deemed it unsafe due to its proximity to the city's large landfill. Limited commercial service to the Cape and Islands, as well as general aviation, is available from New Bedford Regional Airport in nearby New Bedford, Massachusetts. Domestic and international commercial air service is available from T.F. Green Airport, located 13 miles west in Warwick, Rhode Island, and at Logan International Airport, located 45 miles north in Boston, Massachusetts.

Water

[edit]The Fall River Line Pier, located directly beneath the Braga Bridge, is a major port for commercial fishing[79] and cargo shipping, handling imports from and to Cape Verde, the Azores, Brazil, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.[80] A water taxi service began in 2024, connecting the pier to several points throughout the city's waterfront.[81] The port has also served as port-of-call for cruise ships,[82] and formerly served as the terminus for a passenger ferry line connecting to the Rhode Island communities of Newport and Block Island,[83] though the service was cancelled in 2020.[84] The pier also offers connections to freight rail via the Massachusetts Coastal Railroad.

Soccer

[edit]Fall River has a rich soccer history. The game was first introduced to the city in the 1880s by immigrants from Lancashire and Glasgow who worked in the local textile industry. In later decades, the arrival of immigrants from Portugal helped to sustain the game's popularity. Between 1888 and 1892, teams from Fall River won the American Cup for five straight years. One of these teams, the Fall River Rovers, also won the 1917 National Challenge Cup. The star and captain of the team was local-born Thomas Swords, who in 1916 captained the United States in their first official international.

During the 1920s and early 1930s, the Fall River F.C. of Sam Mark were one of the most successful soccer clubs in the United States and were American soccer champions on seven occasions. A subsequent Fall River F.C., were champions in 1932.

The 'Marksmen' won the National Challenge Cup four times. Among their most notable players were Billy Gonsalves and Bert Patenaude, who were both raised in Fall River. Both played for the United States at the first ever soccer World Cup in 1930. Patenaude is also credited with scoring the first ever hat-trick in World Cup history. He scored all three goals in the United States' 3–0 victory over Paraguay.

During the 1940s, Ponta Delgada S.C. became one of the most successful amateur teams in the United States. In 1947 the team was selected to represent the United States at the North American soccer championship. In 1950, two of their local born players, Ed Souza and John Souza, played at the World Cup, helping the United States defeat England 1–0.[85]

On January 18, 2011, Andrew Sousa was drafted by New England Revolution, becoming the first ever Fall River native to play in Major League Soccer.

In 2019, Fall River Football Club and Fall River Marksmen FC returned to the field after a long hiatus. Both clubs participated in the 1st annual Taça de Fall River, a Home & Away match series, with Fall River Football Club becoming the eventual winners.

Points of interest

[edit]

- Battleship Cove, the world's largest historic naval ship exhibit, featuring the USS Massachusetts

- Lincoln Park Carousel,[86] restored 1920 carousel, located at Battleship Cove

- Fall River Heritage State Park, the focal point of Fall River's waterfront

- The Marine Museum at Fall River

- Freetown-Fall River State Forest

- Kennedy Park, North Park and Ruggles Park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted

- Lizzie Borden Bed and Breakfast Museum

- Maplecroft, home of Lizzie Borden from 1894 to her death in 1927[87]

- Oak Grove Cemetery

- Barnard's Folly, a group of historic triple decker tenement houses located on North Main Street[88]

- Granite Mills, two historic cotton textile mills located on Bedford Street[88]

Notable people

[edit]

- Lizzie Borden (1860–1927), tried and acquitted of the 1892 murder of father and step-mother and public speaking teacher in Fall River; is buried with them and the rest of their immediate family in Oak Grove Cemetery

- Nathaniel B. Borden (1801–1865), businessman and politician

- Colonel Richard Borden (1795–1874), mill owner and industrialist

- Dave Brinnel, musician, television producer, radio personality

- David Glendenning Cogan (1908–1993), ophthalmologist

- Jasiel Correia (born 1991), Democrat-politician; arrested twice on charges related to fraud and extortion while in office

- Morton Dean, television and radio anchor, news correspondent and author

- Diesel, born Mark Denis Lizotte, American-born Australian singer-songwriter and musician[89]

- E. J. Dionne, journalist, political commentator

- Robert Dollard, first Attorney General of South Dakota[90]

- Greg Gagne, Major League Baseball shortstop, World Series Champion with the Minnesota Twins in 1987 and 1991

- Kristen Gilbert, serial killer nurse who murdered four patients

- Brandon Gomes, former Major League Baseball player and current Los Angeles Dodgers general manager

- Leslie Gourse, jazz writer, born here in 1939[91]

- Hank the Angry Drunken Dwarf (Henry Joseph Nasiff Jr.), entertainer

- Chris Herren, professional basketball player (Denver Nuggets & Boston Celtics)

- Louie Howe, political advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Thomas J. Hudner, Jr., Naval aviator and Medal of Honor recipient

- Sam Hyde American comedian.

- Napoleon A. L'Herault, lawyer and Minnesota state senators

- Emeril Lagasse, celebrity chef

- Tom Lawlor, professional mixed martial artist

- Marc Megna, American and Canadian football player

- Ernest Moniz, 13th U.S. Secretary of Energy

- John Moriarty, pianist, vocal coach, diction and repertoire professor, New England Conservatory of Music

- Bert Patenaude, professional soccer player, scored the first hat-trick in a World Cup match

- Irving Picard, attorney in the Madoff scandal

- Joe Raposo, songwriter for Sesame Street

- Kimberly Clark Saenz, convicted serial killer and former nurse

- Chris Santos, celebrity chef

- Ronald A. Sarasin, politician

- Winston Sharples, composer known for his work at RKO Radio Pictures and Paramount cartoons

- Andrew Sousa, professional soccer player

- George Stephanopoulos, Good Morning America co-host, born in Fall River[92]

- Tecia Torres, professional mixed martial artist

- Susan H. Wixon (1839–1912), freethought writer, editor, feminist, educator

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Appears to have first been coined in Thayer Lincoln, Jonathan (1909). The City of the Dinner-Pail. Cambridge, Mass.: The Riverside Press; Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Coburn, Frederick William (1920). History of Lowell and Its People. Vol. I. Lewis Publishing Company. p. 345.

For Fall River's rapid rise...the labor union movement has been much more vigorous in 'the City of the Dinner Pail' and at New Bedford than it ever has been in Lowell

- "The Dinner Pail". American Heritage. Vol. XLVII, no. 2. April 1996.

Fall River has been called the City of the Dinner Pail. Although I haven't seen a dinner nail [sic] in many years, I remember it well. It was made of galvanized tin, had three nesting compartments, and a bail handle.

- Coburn, Frederick William (1920). History of Lowell and Its People. Vol. I. Lewis Publishing Company. p. 345.

- ^ Chapter 2-1, Current City Charter Archived September 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, rev. 1995 under ordinance 1995-42.

- "The Municipal Register for 1857, Containing the City Charter, with Rules and Orders of the City Council, and the Ordinances of the City of Fall River". Fall River (Mass.): J.S. Potter. February 8, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Video: Paul Coogan takes over as mayor of Fall River". The Herald News.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ "A Rallying Cry for the Dream Chasers, A Mantra for the Hard Workers: Fall River Case Study". Figmints Digital Creative Marketing. February 17, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Stevens, Elizabeth C. Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman: A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist, and Workers' Rights Activism. United States: McFarland Publishing, 2003.

- ^ Ira V. Brown, ""Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?" The Anti Slavery Convention of American Women, 1837-1839", Pennsylvania State University

- ^ The Run of the Mill, Dunwell, Steve, 1978

- ^ "The Fall River Iron Works Prospered After Shaky Start", Fall River Herald News, October 17, 1989 Archived December 27, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Illustrated History of Fall River, 1903" (PDF).

- ^ The Run of the Mill, Dunwell, Steve, 1978, p.105-110

- ^ 2003 "Local Rock Vital in City's Construction", Herald News, February 26, 2003

- ^ U.S. Census. 1940 Population Reports. p. 32

- ^ Sailsinc.org Picture of the Worst Fire in Fall River's History

- ^ "Keeley Library, B.M.C. Durfee High School - Full-text Online Books & Articles". sailsinc.org.

- ^ "MHC Survey, 1982" (PDF).

- ^ History of Fall River's Garment Industry Archived June 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Valle's Steak House, opened in 1970 and demolished in 1984" (August 6, 2012) The Herald News (Fall River, Mass.)[1]

- ^ Schiller, Andrew (January 2, 2021). "NeighborhoodScout's Most Dangerous Cities - 2021". Neighborhoodscout.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Northeast Alternatives Story". Northeast Alternatives. Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Fall River city, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Fall River, MA 7.5 by 15-minute quadrangle, 1985.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fall River has 23 parks and playgrounds for recreational fun". Fall River Herald News. May 15, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Dion, Marc Munroe (May 15, 2011). "OLMSTED FACTS: Frederick Law Olmsted famed for parks nationwide". Fall River Herald News. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Fall River". South Coast Bikeway. Archived from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, pp. 21-7 – 21-09, Massachusetts Table 4. Population of Urban Places of 10,000 or more from Earliest Census to 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Fall River city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Fall River city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Fall River city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b General Demographic Characteristics for Fall River Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ University of Massachusetts Dartmouth p. 8 Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ancestry Search – Genealogy by City". epodunk.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Households and Families 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c Jasinski, Peter (September 27, 2019). "Flags vanish from downtown Fall River, but for a good reason". Fall River Herald News. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

Intended as a way to represent the city's diverse population and the nations they hailed from, the flags honored a variety of countries including Lebanon, Greece and Brazil.

- ^ a b da Silva, Lurdes (July 29, 2024). [On Thursday, Aug. 22, at 7 p.m., a special illumination ceremony will turn on thousands of bulbs, lighting up the giant crown in Kennedy Park, representing the Holy Spirit, and other decorations on the feast grounds. "Fall River's Great Feast of the Holy Ghost: Your guide to parades, music, food and more"]. O Jornal. South Coast Today. Archived from the original on August 2, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

{{cite news}}: Check|archive-url=value (help) - ^ "O Jornal". The Herald News, Fall River, MA.

- ^ "Fall River Celebrates America canceled".

- ^ narrowsadmin (October 5, 2011). "Live Music - Fall River, MA Waterfront". www.narrowscenter.org. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Linda. "Fall River's new contemporary art museum, FR MoCA, opens Friday". The Herald News. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "About Us — FR MoCA". frmoca.org. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "List of Parishes". Fall River Diocese. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Stewardson, Jack (May 23, 2000). "Another Fall River church will close". South Coast Today. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Encyclopedia Judaica: Fall River, Massachusetts". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ Linton, David. "News organizations flock to Aaron Hernandez murder trial". The Sun Chronicle. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Massachusetts Senatorial Districts". Sec.state.ma.us. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Elections Division. "State Senate elections: 1st Bristol and Plymouth district". Sec.state.ma.us. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ "Feb. 2019 MA Party Enrollment" (PDF). Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Galvin, William. "Public Document 43". electionstats.state.ma.us.

- ^ "About Us". Atlantis Charter School. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Bishop Feehan High School :: History". www.bishopfeehan.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "History of Espirito Santo School Archived 2011-12-22 at the Wayback Machine." Espirito Santo School. Retrieved on August 21, 2012.

- ^ "ENC's Adult and Graduate Studies Program expands into satellite locations around the state". Nazarene Communications Network. December 18, 2008. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ C.B. Tillinghast. The free public libraries of Massachusetts. 1st Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1891.

- ^ Fall River Public Library Archived September 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 11, 2010

- ^ City of Fall River. 2021. FY 2022 Budget. Retrieved from https://www.fallriverma.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/FY-22-Budget_5-7-21.pdf

- ^ "Fall River Public Library Branches". fallriverlibrary.org. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "Fall River Historical Society – North American Reciprocal Museum (NARM) Association®". Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Dion, Marc Munroe. "The name on the Braga Bridge is about more than steel and asphalt". The Herald News, Fall River, MA. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ writers, Ric Oliveira and Mary Jo Curtis, Standard-Times staff. "Overpass crumbles". New Bedford Standard-Times. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "SRTA – Southeastern Regional Transit Authority". www.srtabus.com. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Holtzman, Michael. "Officials on hand for dedication of SRTA's new transportation center". The Herald News, Fall River, MA. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "24L | Newport/Fall River/Providence". RIPTA. May 22, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Peter Pan Bus Lines | Better. Quicker. Safer". Peter Pan Bus Lines. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Commercial Fishing". Fall River Line Pier. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Shipping". Fall River Line Pier. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Allegra Zamore (May 27, 2024). "Fall River water taxi begins service at city's waterfront". NBC. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "Cruise". Fall River Line Pier. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Fall River Hi-Speed Schedule". Block Island Ferry. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Winokoor, Charles. "Why the Fall River to Block Island ferry run is canceled for the second season in a row". The Herald News. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Soccer in a Football World - The Story of America's Forgotten Game (2006) : David Wangerin amazon.com

- ^ Battleshipcove.org Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Allard, Deborah. "Lizzie Borden's Maplecroft estate is up for sale again".

- ^ a b Giza, Patricia (1984). A Guide Book to Fall River's National Register Properties. Fall River, Massachusetts: The City.

- ^ "Mark Lizotte aka Johnny Diesel | Australian Music Database".

- ^ Executive Committee (April 14, 1900). Souvenir Program, Association of Mass. Minute Men of '61: Celebration of the Thirty-Ninth Anniversary. Boston, MA: Geo. W. Nason. p. 70.

- ^ "Leslie Gourse, 65, Biographer of Jazz Artists". The New York Times. January 5, 2005.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Lawmaker reacts to Trump's State of the Union address". YouTube.

External links

[edit]- Fall River official website

- Preservation Society of Fall River

- Beers, D.G. 1872 Atlas of Essex County Map of Massachusetts Plate 5. Click on the map for a very large image. Also see detailed map of 1872 Essex County Plate 7.

- Fall River History, Old Newspaper Articles, Genealogy

- Fall River, Massachusetts

- 1670 establishments in Plymouth Colony

- Cities in Bristol County, Massachusetts

- Cities in Massachusetts

- History of the textile industry

- Populated coastal places in Massachusetts

- Populated places established in 1670

- Portuguese-American culture in Massachusetts

- Portuguese neighborhoods in the United States

- Providence metropolitan area