Economic history of Indonesia

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The economic history of Indonesia is shaped by its geographic location, its natural resources, as well as its people that inhabited the archipelago that today formed the modern nation-state of the Republic of Indonesia. The foreign contact and international trade with foreign counterparts had also shaped and sealed the fate of Indonesian archipelago, as Indians, Chinese, Arabs, and eventually European traders reached the archipelago during the Age of Exploration and participated in the spice trade, war and conquest.

By the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC), one of the world's earliest multinational companies, had established their base in the archipelago as they monopolised the spice trade. By 1800, the Dutch East Indies colonial state had emerged and benefited from cash crop trades of coffee, tea, quinine, rubber and palm oil from the colony, also from the mining sector: oil, coal, tin and copper. The colonial state would be succeeded by the Indonesian Republic after World War II.

By the early 21st century, Indonesia rose to be the largest economy in Southeast Asia, as one of the emerging market economies of the world, a member of G-20 major economies and classified as a newly industrialised country.[1]

Pre-modern Indonesia

[edit]Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms period

[edit]The economy of most of villages and polities in the archipelago initially relied heavily on rice agriculture, as well as the trading of forests products such as tropical fruits, hunted animals, plant resins, rattan and hardwood. Ancient kingdoms such as the Tarumanagara and Mataram were dependent on rice yields and tax.

For a long time, the archipelago was known for its abundance of natural resources. Spices such as nutmeg and cloves from Maluku Islands, pepper and cubeb from southern Sumatra and western Java, rice from Java, gold, copper and tin from Sumatra, Borneo and the islands in between, camphor resin from port of Barus, sappan and sandalwood from the Lesser Sunda Islands, hardwoods from Borneo, ivory and rhino's horn from Sumatra and exotic bird feathers from the Western New Guinea are among a few products sought by traders worldwide. This foreign contact was started by small Indianised trading kingdoms in the early 4th century that nurtured contacts with other major civilisations in the Asian mainland, India and China. Benefited by its strategic location on a thriving maritime trade route between India and China, polities in Indonesian archipelago soon would grow into a thriving, healthy, and cosmopolitan trading empire such as Srivijaya that rose in the 7th century.

Srivijaya

[edit]In the world of commerce, Srivijaya rose rapidly to be a far-flung empire controlling the two passages between India and China, namely the Sunda Strait from Palembang and the Malacca Strait from Kedah. Arab accounts stated that the empire of the maharaja was so vast that in two years the swiftest vessel could not travel round all its islands, which produced camphor, aloes, cloves, sandalwood, nutmegs, cardamom and cubebs, ivory, gold and tin, making the maharaja as rich as any king in India.[2]

Other than fostering the lucrative trade relations with India and China, Srivijaya also established commerce link with the Arabian Peninsula. A messenger sent by Maharaja Sri Indravarman delivered his letter for Caliph Umar ibn AbdulAziz of Ummayad in 718 and was returned to Srivijaya with Zanji (black female slave from Zanj), the Caliph's present for maharaja. The Chinese chronicle later mentioned about Che-li-t'o-lo-pa-mo (Sri Indravarman), Maharaja of Shih-li-fo-shih in 724 had sent the emperor a ts'engchi (Chinese spelling of Arabic Zanji) as a gift.[3] Srivijaya would continue to dominate the economy of the archipelago until its decline in the 13th century.

Majapahit

[edit]

In the 14th century Java, the Majapahit kingdom would grow into a maritime empire that would control the trade and economy of the archipelago for another century. According to a Chinese source from Ming Dynasty, Yingya Shenglan, Ma Huan reported on the Javanese economy and market. Rice is harvested twice a year, and its grain is small. They also harvest white sesame and lentils, but there is no wheat. This land produces sapan wood (useful to produce red dye), diamond, sandalwood, incense, puyang pepper, cantharides (green beetles used for medicine), steel, turtles, tortoise shell, strange and rare birds; such as a large parrot as big as a hen, red and green parrots, five-coloured parrots that can imitate the human voice, also guinea fowl, peacock, 'betel tree bird', pearl bird, and green pigeons. The beasts here are strange: there are white deer, white monkey, and various other animals. Pigs, goats, cattle, horses, poultries, and there are all types of ducks.[4] For the fruits, there are all kinds of bananas, coconut, sugarcane, pomegranate, lotus, mang-chi-shi (mangosteen), watermelon and lang Ch'a (langsat or lanzones). In addition, all types of squash and vegetables are present.[4]

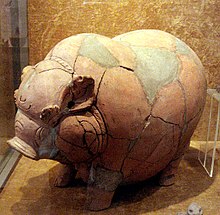

Taxes and fines were paid in cash. The Javanese economy had been partly monetised since the late 8th century by using gold and silver coins. Previously, the 9th-century Wonoboyo hoard discovered in Central Java shows that ancient Javan gold coins were seed-shaped similar to corn, while the silver coins were similar to buttons. Around 1300, during the reign of Majapahit's first king, an important change took place: the indigenous coinage was replaced entirely by imported Chinese copper cash. About 10,388 ancient Chinese coins weighing about 40 kg were unearthed from the backyard of a local resident in Sidoarjo in November 2008. Indonesian Ancient Relics Conservation Bureau (BP3) of East Java verified that the coins dated as early as the Majapahit era.[5] The reason for the use of foreign currency is not given in any source, but most scholars assume it was due to the increasing complexity of Javanese economy and a desire for a currency system that used much smaller denominations suitable for use in everyday market transactions. This was a role for which gold and silver are not well suited.[6]: 107 These kepeng Chinese coins were thin rounded copper coins with a square hole in the centre of it, meant to tie together the money in a string of coins. These small changes—the imported Chinese copper coins—enabled Majapahit further invention, a method of savings by using a slitted earthenware coin containers. These are commonly found in Majapahit ruins; the slit is the small opening to put the coins in. The most popular shape is boar-shaped celengan (piggy bank).

Some ideas for the scale of the internal economy can be gathered from scattered data in inscriptions. The Canggu inscriptions dated 1358 mentions 78 ferry crossings in the country (mandala Java).[6]: 107 Majapahit inscriptions mention a large number of occupational specialities, ranging from gold and silver smiths to drink vendors and butchers. Although many of these occupations had existed in earlier times, the proportion of the population earning an income from non-agrarian pursuits seems to have become even more significant during the Majapahit era.

The great prosperity of Majapahit was probably due to two factors. First, the northeast lowlands of Java were suitable for rice cultivation, and during Majapahit's prime, numerous irrigation projects were undertaken, some with government assistance. Second, Majapahit's ports on the north coast were probably significant stations along the route to obtain the spices of Maluku, and as the spices passed through Java, they would have provided an essential source of income for Majapahit.[6]: 107

The Nagarakertagama states that the fame of the ruler of Majapahit attracted foreign merchants from afar, including Indians, Khmers, Siamese, and Chinese, among others. While in a later period, Yingya Shenglan mentioned that large numbers of Chinese traders and Muslim merchants from the west (from Arab and India, but mostly from Muslim states in Sumatra and Malay peninsula) are settling in Majapahit port cities, such as Tuban, Gresik and Hujung Galuh (Surabaya). A special tax was levied against some foreigners, possibly those who had taken up semi-permanent residence in Java and conducted some type of enterprise other than foreign trade. The Majapahit Empire had trading links with Chinese Ming dynasty, Annam and Champa in present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, Siamese Ayutthayan, Burmese Martaban and the south Indian Vijayanagara Empire.

Spread of Islam and Muslim trading network

[edit]

The Muslim traders had spread the Islamic faith across the trade routes that connect to the Islamic World. The routes spanned from the Mediterranean, the Middle East, India, Maritime Southeast Asia to China. Muslim traders from the Arabian peninsula and the Persian Gulf have sailed the Indonesian archipelago on their way to China since at least the 9th century, as testified through the discovery of Belitung shipwreck that contains cargoes from China, discovered offshore of Belitung island. The Muslim traders and proselytiser had encouraged the rise of Islamic states in the archipelago. By the 13th century, Islam had gained its foothold in the archipelago through the establishment of Samudra Pasai in Aceh and Ternate Sultanate in the Maluku Islands. The spice-producing Maluku islands gained its name from Arabic "Jazirat al Muluk" which means "the peninsula or islands of kings".

By the 14th century, these Muslim ports began to thrive as they welcome Muslim traders from India and the Middle East. Among the most notable Muslim kingdoms are the Malacca Sultanate that control the strategic Malacca Strait and the Demak Sultanate that replaced Majapahit as the regional power in Java. Both were also active in spreading Islam in the archipelago, and by the late 15th century, Islam has supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism in Java and Sumatra, and Sulawesi and northern Maluku as well. The Islamic polities in the archipelago formed parts of the more extensive Islamic trading networks that spanned from Al-Andalus in the West to Muslim trading colonies in Chinese ports of the East, as spices from Indonesia like cloves, nutmeg and pepper could reach spice markets in Canton, Damascus and Cairo.

Colonial era

[edit]The arrival of Europeans and the spice and cash-crop trade

[edit]

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach the Indonesian archipelago. Their quest to dominate the source of the lucrative spice trade in the early 16th century, and their simultaneous Roman Catholic missionary efforts, saw the establishment of trading posts and forts, and a strong Portuguese cultural element that remains substantial in modern Indonesia. Starting with the first exploratory expeditions sent from the newly-conquered Malacca in 1512, the Portuguese fleet began to explore much of archipelago and sought to dominate the sources of valuable spices.[7] However, the Portuguese presence was later reduced to Solor, Flores and Timor (see Portuguese Timor) in modern-day Nusa Tenggara, due to their 1575 defeat at Ternate at the hands of indigenous Ternateans, and its defeat to the Dutch.

In the early 17th century, the VOC was founded. Its main business was profiting in intra-Asian trade and establishing direct spice trade between the archipelago and Europe. One by one, the Dutch began to wrestle Portuguese possessions that started with Dutch conquests in Ambon, northern Maluku and Banda, and a general Portuguese failure for sustained control of trade in the region.[8] Statistically, the VOC eclipsed all of its rivals in the Asian trade. Between 1602 and 1796, the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asian trade on 4,785 ships and netted for their efforts more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 17th century.[9] VOC took huge profit from monopolising the Maluku spice trade, and in 1619 the VOC established a capital in the port city of Jacatra and changed the city name into Batavia (present-day Jakarta). Over the next two centuries, the VOC acquired additional ports as trading bases and safeguarded their interests by taking over surrounding territory.[10] It remained a paramount trading concern and paid an 18% annual dividend for almost 200 years.[11]

Dutch East Indies

[edit]

The Dutch East Indies was formed from the nationalised colonies of the VOC, which came under the administration of the Dutch government in 1800. The economic history of the colony was closely related to the economic health of the Netherlands.[12] Despite increasing returns from the Dutch system of land tax, Dutch finances had been severely affected by the cost of the Java War and the Padri War, and the loss of Belgium in 1830 brought the Netherlands to the brink of bankruptcy. In 1830, a new Governor-General, Johannes van den Bosch, was appointed to make the Indies pay their way through the Dutch exploitation of its resources. With the Dutch achieving political domination throughout Java for the first time in 1830,[13] it was possible to introduce an agricultural policy of government-controlled forced cultivation. Termed cultuurstelsel (cultivation system) in Dutch and tanam paksa (forced plantation) in Indonesian, farmers were required to deliver fixed amounts of specified crops such as sugar or coffee as a form of tax.[14] Much of Java eventually became a Dutch plantation and revenue rose continually through the 19th century which were reinvested into the Netherlands to save it from bankruptcy.[14][15] Between 1830 and 1870, one billion guilders were taken from the archipelago, which on average, making 25% of the annual Dutch government budget.[16] The Cultivation System, however, brought much economic hardship to the Javanese peasants who suffered famine and epidemics in the 1840s.[15]

The system proved disastrous for the local population; at its height, over 1 million farmers worked under the Cultuurstelsel and the extreme incentive for profit resulted in widespread abuses. Farmers were often forced to either use more than 20% of their farmland, or the most fertile land, for cultivation of cash crops. The system led to an increase in famine and disease among the local population. It is estimated that mortality rates increased by as much as 30% during this period.[17]

Critical public opinion in the Netherlands led to much of the Cultivation System's excesses being eliminated under the agrarian reforms of the "Liberal Period." Dutch private capital flowed in after 1850, especially in tin mining and plantation estate agriculture. The Billiton Company's tin mines off the eastern Sumatra coast was financed by a syndicate of Dutch entrepreneurs, including the younger brother of King William III. Mining began in 1860. In 1863, Jacob Nienhuys obtained a concession from the Sultanate of Deli for a large tobacco estate.[18] The Dutch East Indies were opened up to private enterprise, and Dutch business people set up large, profitable plantations. Sugar production doubled between 1870 and 1885. New crops such as tea and cinchona flourished, and rubber was introduced, leading to dramatic increases in Dutch profits. Changes were not limited to Java or agriculture; oil from Sumatra and Borneo became a valuable resource for industrialising Europe. Dutch commercial interests expanded off Java to the outer islands with increasingly more territory coming under direct Dutch control or dominance in the latter half of the 19th century.[15] However, the resulting scarcity of land for rice production, combined with dramatically increasing populations, especially in Java, led to further hardships.[15]

The colonial exploitation of the archipelago's wealth contributed to the industrialisation of the Netherlands, while simultaneously laying the foundation for the industrialisation of Indonesia. The Dutch introduced coffee, tea, cacao, tobacco and rubber and large expanses of Java became plantations cultivated by Javanese peasants, collected by Chinese intermediaries, and sold on overseas markets by European merchants.[15] In the late 19th century, economic growth was based on substantial world demand for tea, coffee, and cinchona. The government invested heavily in a railroad network (150 miles long in 1873, 1,200 in 1900), as well as telegraph lines, and entrepreneurs opened banks, shops and newspapers. The Dutch East Indies produced most of the world's supply of quinine and pepper, over a third of its rubber, a quarter of its coconut products, and a fifth of its tea, sugar, coffee, and oil. The profit from the Dutch East Indies made the Netherlands one of the world's most significant colonial powers.[15] The Royal Packet Navigation Company shipping line supported the unification of the colonial economy and brought inter-island shipping through to Batavia, rather than through Singapore, thus focusing more economic activity on Java.[19]

The worldwide recession of the late 1880s and early 1890s saw the commodity prices on which the colony depended collapse. Journalists and civil servants observed that the majority of the Indies population were no better off than under the previous regulated Cultivation System economy and tens of thousands starved.[20] Commodity prices recovered from the recession, leading to increased investment in the colony. The sugar, tin, copra and coffee trade on which the colony had been built thrived, and rubber, tobacco, tea and oil also became principal exports.[21] Political reform increased the autonomy of the local colonial administration, moving away from central control from the Netherlands, while power was also diverged from the central Batavia government to more localised governing units.

The world economy recovered in the late 1890s and prosperity returned. Foreign investment, especially by the British, were encouraged. By 1900, foreign-held assets in the Dutch East Indies totalled about 750 million guilders ($300 million), mostly in Java.[22]

After 1900, upgrading the infrastructure of ports and roads was a high priority for the Dutch, with the goal of modernising the economy, facilitating commerce, and speeding up military movements. By 1950, Dutch engineers had built and upgraded a road network with 12,000 km of asphalted surface, 41,000 km of metalled road area and 16,000 km of gravel surfaces.[23] In addition, the Dutch built 7,500 kilometres (4,700 mi) of railways, bridges, irrigation systems covering 1.4 million hectares (5,400 sq mi) of rice fields, several harbours, and 140 public drinking water systems. Wim Ravesteijn has said that "With these public works, Dutch engineers constructed the material base of the colonial and postcolonial Indonesian state."[24][25]

The Japanese occupation

[edit]The Dutch East Indies fell to invading forces of the Japanese Empire in 1942. During World War II, the economy of Dutch East Indies was more or less crumbled, as every resource was directed toward war efforts of the empire, as the Japanese occupation forces applied strict martial policies. Many basic necessities such as food, clothing and medicine are scarce, and some regions even suffered famine. By early 1945, Japanese forces began to lose the war, culminating in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

During the Japanese occupation, the average height of the Indonesian population has decreased. As the change of a population's average height can be interpreted as a sign of economic development, Baten, Stegl and van der Eng found out that the people in Indonesia were able to grow on average after the occupation since the establishment of food or medical supply and a reduction of diseases was reassured. Thus, due to enhanced nutrition and medical supply (therefore an increase of the average height), the Indonesian economy was able to improve after the Japanese occupation.[26]

Modern era

[edit]Sukarno presidency

[edit]

On 17 August 1945, Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta proclaimed the independence of Indonesia. Amid the turmoil, Indonesia issued its first rupiah banknotes in 1945. Between 1945 and 1949, Indonesia was embroiled in a war of independence against Dutch re-colonisation efforts. The economic conditions were plunged into chaos, especially in Java and Sumatra, as people struggled to survive the war.

In the 1960s, the economy deteriorated drastically as a result of political instability. Indonesia had a young and inexperienced government, which resulted in severe poverty and hunger. By the time of Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment.

Suharto presidency

[edit]

Following President Sukarno's downfall, the New Order administration brought a degree of discipline to economic policy that quickly brought inflation down, stabilised the currency, rescheduled foreign debt, and attracted foreign aid and investment. (See Berkeley Mafia). Indonesia was until recently Southeast Asia's only member of OPEC, and the 1970s oil price hike provided an export revenue windfall that contributed to sustained high economic growth rates, averaging over 7% from 1968 to 1981.[27] GDP per capita grew 545% from 1970 to 1980 as a result of the sudden increase in oil export revenues from 1973 to 1979.[28] Due to high levels of regulation and dependence on declining oil prices, the growth slowed to an average of 4.3% per annum between 1981 and 1988. Subsequently, a range of economic reforms were introduced in the late 1980s including a managed devaluation of the rupiah to improve export competitiveness, and deregulation of the financial sector.[29] Foreign investment flowed into Indonesia, particularly into the rapidly developing export-oriented manufacturing sector. As a result, the economy grew by an average of over 7% from 1989 to 1997.[30][31]

Such high growth, however, masked several structural weaknesses in the economy. Growth came at a high cost in terms of weak and corrupt institutions, severe public indebtedness through mismanagement of the financial sector, the rapid depletion of Indonesia's natural resources, and culture of favours and corruption in the business elite.[32] Corruption particularly gained momentum in the 1990s, reaching to the highest levels of the political hierarchy. As a result, the legal system was fragile, and there was no effective way to enforce contracts, collect debts, or sue for bankruptcy. Banking practices were very unsophisticated, with collateral-based lending the norm and widespread violation of prudential regulations, including limits on connected lending. Non-tariff barriers, rent-seeking by state-owned enterprises, domestic subsidies, barriers to domestic trade and export restrictions all contributed to economic distortions.

1997 Asian financial crisis

[edit]

The 1997 Asian financial crisis that began to affect Indonesia mid-year became an economic and political crisis. Indonesia's initial response was to float the rupiah, raise key domestic interest rates, and tighten fiscal policy. In October 1997, Indonesia and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reached agreement on an economic reform program aimed at macroeconomic stabilisation and elimination of some of the country's most damaging economic policies, such as the National Car Program and the clove monopoly, both involving family members of President Suharto. The rupiah remained weak, however, and President Suharto was forced to resign in May 1998. In August 1998, Indonesia and the IMF agreed on an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) under President B. J. Habibie that included significant structural reform targets. Abdurrahman Wahid took office as president in October 1999, and Indonesia and the IMF signed another EFF in January 2000. The new program also has a range of economic, structural reform and governance targets.

The effects of the financial and economic crisis were severe. By November 1997, rapid currency depreciation had seen public debt reach US$60 billion, imposing severe strains on the government's budget.[34] In 1998, real GDP contracted by 13.1%. The economy reached its low point in mid-1999, and real GDP growth for the year was 0.8%. Inflation reached 72% in 1998 but slowed to 2% in 1999. The rupiah, which had been in the Rp 2,600/USD1 range at the start of August 1997 fell to 11,000/USD1 by January 1998, with spot rates around 15,000 for brief periods during the first half of 1998.[35] It returned to 8,000/USD1 range at the end of 1998 and has generally traded in the Rp 8,000–10,000/USD1 range ever since, with fluctuations that are relatively predictable and gradual.

Post-Suharto era

[edit]In late 2004, Indonesia faced a 'mini-crisis' due to international oil prices rises and imports. The currency reached Rp 12,000/USD1 before stabilising. The government was forced to cut its massive fuel subsidies in October, which were planned to cost $14 billion for 2005.[36] This led to a more than doubling in the price of consumer fuels, resulting in double-digit inflation. The situation eventually stabilised, but the economy continued to struggle with inflation at 17% in 2005.

Economic growth accelerated to 5.1% in 2004 and reached 5.6% in 2005. For 2006, Indonesia's economic outlook was more positive. Real per capita income has reached fiscal year of 1996/1997 levels. Growth was driven primarily by domestic consumption, which accounts for roughly three-fourths of Indonesia's gross domestic product. The Jakarta Stock Exchange was the best performing market in Asia in 2004 up by 42%. Problems that continue to put a drag on growth include low foreign investment levels, bureaucratic red tape, and pervasive corruption which causes 51.43 trillion rupiah or (US$5.6 billion) or approximately 1.4% of GDP to be lost annually.[37] However, there was unyielding optimism with the conclusion of peaceful elections during 2004 and the election of the reformist president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

The unemployment rate in February 2007 was 9.75%.[38] Despite a slowing global economy, Indonesia's economic growth accelerated to a ten-year high of 6.3% in 2007. This growth rate was sufficient to reduce poverty from 17.8% to 16.6% based on the government's poverty line and reversed the recent trend towards jobless growth, with unemployment falling to 8.46% in February 2008.[39][40] Unlike many of its more export-dependent neighbours, Indonesia managed to skirt the Great Recession, helped by strong domestic demand (which makes up about two-thirds of the economy) and a government fiscal stimulus package of about 1.4% of GDP. After India and China, Indonesia became the third-fastest growing economy in the G20. The $512-billion-economy expanded 4.4% in the first quarter from a year earlier, and in the previous month, the IMF revised its 2009 forecast for the country to 3-4% from 2.5%. Indonesia enjoyed stronger fundamentals with the implementation of wide-ranging economic and financial reforms, including a rapid reduction in public and external debt, strengthening of corporate and banking sector balance sheets and reduction of bank vulnerabilities through higher capitalisation and better supervision.[41] The unemployment rate of Indonesia for 2012 is at 6% as per Vice-President of Indonesia Dr. Boediono.[42]

In late 2020, Indonesia fell into its first recession in 22 years due to the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic.[43]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Hup, Mark (2024). "Labor coercion, fiscal modernization, and state capacity: Evidence from colonial Indonesia". Explorations in Economic History

References

[edit]- ^ "About the G20". G20.

- ^ Marwati Djoened Poesponegoro, Nugroho Notosusanto, (1992), Sejarah nasional Indonesia: Jaman kuna, PT Balai Pustaka, ISBN 979-407-408-X

- ^ Azra, Azyumardi (2006). Islam in the Indonesian world: an account of institutional formation. Mizan Pustaka. ISBN 979-433-430-8.

- ^ a b Ma Huan (1970) [1433]. Ying-yai Sheng-lan (瀛涯胜览) The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores. Hakluyt Society (in Chinese). translated by J.V.G Mills. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521010320.

- ^ "Uang Kuno Temuan Rohimin Peninggalan Majapahit". Kompas.com. November 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c John Miksic, ed. (1999). Ancient History. Indonesian Heritage Series. Vol. 1. Archipelago Press / Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9813018267.

- ^ Ricklefs, M.C (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, second edition. London: MacMillan. pp. 22–24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- ^ Miller, George, ed. (1996). To The Spice Islands and Beyond: Travels in Eastern Indonesia. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. xv. ISBN 967-65-3099-9.

- ^ Van Boven, M. W. "Towards A New Age of Partnership (TANAP): An Ambitious World Heritage Project (UNESCO Memory of the World – reg.form, 2002)". VOC Archives Appendix 2, p.14.

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 10

- ^ Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 110. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- ^ Dick, et al. (2002)

- ^ Ricklefs (1991), p 119

- ^ a b Taylor (2003), p. 240

- ^ a b c d e f *Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. pp. 23–25. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

- ^ "Indonesia's Infrastructure Problems: A Legacy from Dutch Colonialism | the Jakarta Globe". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ P. de Zwart, D. Gallardo-Albarrán, A.: ‘The Demographic Effects of Colonialism: Forced Labor and Mortality in Java 1834-1879’, Wageningen University & Research (WUR) & Universiteit Utrecht, 2021

- ^ Dick, et al. (2002), p. 95

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 20

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 16

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 18

- ^ Dick, et al. (2002), p. 97

- ^ Marie-Louise ten Horn-van Nispen and Wim Ravesteijn, "The road to an empire: Organisation and technology of road construction in the Dutch East Indies, 1800-1940," Journal of Transport History (2009) 10#1 pp 40-57

- ^ Wim Ravesteijn, "Between Globalization and Localization: The Case of Dutch Civil Engineering in Indonesia, 1800–1950," Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, 5#1 (2007) pp. 32–64, quote p 32

- ^ [1] Archived 16 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Baten, Jörg; Stegl, Mojgan; van der Eng, Pierre: “Long-Term Economic Growth and the Standard of Living in Indonesia

- ^ Schwarz (1994), pp. 52–7.

- ^ "GDP info". Earthtrends.wri.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ (Schwarz (1994), pages 52–57)

- ^ Schwarz (1994), pages 52–57.

- ^ "Indonesia: Country Brief". Indonesia: Key Development Data & Statistics. The World Bank. September 2006.

- ^ "Combating Corruption in Indonesia, World Bank 2003" (PDF). Siteresources.worldbank.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2005. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Indonesia Floats the Rupiah, And It Drops More Than 6%". The New York Times. 15 August 1997. p. D6. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ Robison, Richard (17 November 2009). "A Slow Metamorphosis to Liberal Markets". Australian Financial Review.

- ^ "Historical Exchange Rates". OANDA. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ BBC News (31 August 2005). "Indonesia plans to slash fuel aid". BBC, London.

- ^ "The Jakarta Post -". 14 December 2007. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Beberapa Indikator Penting Mengenai Indonesia" (PDF) (Press release) (in Indonesian). Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau. 2 December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ "Indonesia: Economic and Social update" (PDF) (Press release). World Bank. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ "Indonesia: BPS-STATISTICS INDONESIA STRATEGIC DATA" (PDF) (Press release). BPS-Statistic Indonesia. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "IMF Survey: Indonesia's Choice of Policy Mix Critical to Ongoing Growth". Imf.org. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Vice President: Indonesia will move on". Investvine.com. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Akhlas, Adrian Wail (5 November 2020). "Breaking: Indonesia enters first recession since 1998 on 3.49% Q3 contraction". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.