Classical Realism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

Classical Realism is an artistic movement in the late-20th and early 21st century in which drawing and painting place a high value upon skill and beauty, combining elements of 19th-century neoclassicism and realism.

Origins

[edit]

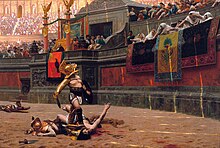

The term "Classical Realism" first appeared as a description of literary style, as in an 1882 criticism of Milton's poetry.[1] Its usage relating to the visual arts dates back to at least 1905 in a reference to Masaccio's paintings.[2] It originated as the title of a contemporary but traditional artistic movement with Richard Lack (1928–2009), who was a pupil of Boston artist R. H. Ives Gammell (1893–1981) during the early 1950s. Ives Gammell had studied with William McGregor Paxton (1869–1941) and Paxton had studied with 19th-century French artist, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904). In 1967 Lack established Atelier Lack, a studio-school of fine art patterned after the ateliers of 19th-century Paris and the teaching of the Boston impressionists. By 1980 he had trained a significant group of young painters. In 1982, they organized a traveling exhibition of their work and that of other artists within the artistic tradition represented by Gammell, Lack and their students. Lack was asked by Vern Swanson, director of the Springville Museum of Art, Springville, Utah, (the exhibition's originating venue), to coin a term that would differentiate the realism of the heirs of the Boston tradition from that of other representational artists. Although he was reluctant to label this work, Lack chose the expression "Classical Realism." It was first used in the title of that exhibition: Classical Realism: The Other Twentieth Century. The term, "Classical Realism", was originally intended to describe work that combined the fine drawing and design of the European academic tradition as exemplified by Gérôme with the observed color values of the American Boston tradition as exemplified by Paxton.

In 1985 Atelier Lack began publishing the Classical Realism Quarterly, featuring articles written by Richard Lack and his students to educate and inform the public about traditional representational painting. In 1988 Lack and several associates founded The American Society of Classical Realism, a society organized to preserve and promote fine representational art. The ASCR functioned until 2005 and published the influential Classical Realism Journal and Classical Realism Newsletter.

In a separate vein, another major contributor to the revival of traditional drawing and painting knowledge is the painter and art instructor Ted Seth Jacobs (born 1927), who taught students at the Art Students League and the New York Academy of Art in New York City.[3] Their lineage is rooted in the Académie Julian, the Golden Age of Illustration in New York, and the School of Paris. In 1987 Ted Seth Jacobs created his own art school, L'Ecole Albert Defois in Les Cerqueux sous Passavant, France (49). Many of Jacobs' students such as Anthony Ryder and Jacob Collins became influential teachers and acquired their own student following.[4]

Style and philosophy

[edit]Classical Realism is characterized by love for the visible world and the great traditions of Western art, including Classicism, Realism and Impressionism. The movement's aesthetic is classical in that it exhibits a preference for order, beauty, harmony and completeness; it is realist because its primary subject matter comes from the representation of nature based on the artist's observation.[5] Artists in this genre strive to draw and paint from the direct observation of nature, and eschew the use of photography or other mechanical aids. In this regard, Classical Realism differs from the art movements of Photorealism and Hyperrealism, as well as from industry methods as used in disciplines such as concept art. Stylistically, classical realists employ methods used by both Impressionist and Academic artists.

Classical Realist painters have attempted to restore curricula of training that develop a sensitive, artistic eye and methods of representing nature that pre-date Modern Art. They seek to create paintings that are personal, expressive, beautiful, and skillful. Their subject matter includes all of the traditional categories within Western Art: figurative, landscape, portraiture, indoor and outdoor genre and still life paintings.

A central idea of Classical Realism is the belief that the Modern Art movements of the 20th century opposed the tenets and production of traditional art and caused a general loss of the skills and methods needed to produce it. Modernism was antagonistic to art as it was conceived by the Greeks, resurrected in the Renaissance, and carried on by the academies of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[6] Classical Realist artists attempt to revive the idea of art production as it was traditionally understood: mastery of a craft in order to make objects that gratify and ennoble those who see them.[7] This craftsmanship is then applied to drawing, painting or sculpting contemporary subjects which the artist observes in the modern world.

Like the 19th-century academic models from which it derives inspiration, the movement has drawn criticism for the premium placed upon technical performance, a tendency toward contrived and idealized depictions of the figure, and rhetorical overstatement when applied to epic narrative.[6] Maureen Mullarkey of the New York Sun referred to the school as "a contemporary style with retro appeal—like Chrysler's PT Cruiser".[8]

Schools

[edit]The Classical Realist movement is currently sustained through art schools based on the Atelier Method. Many present-day academies and ateliers follow the Charles Bargue drawing course. Richard Lack is generally regarded as the founder of the contemporary atelier movement. His school, Atelier Lack, was founded in 1969 and became a model for similar schools.[9] These modern ateliers are founded with the goal of revitalizing art education by reintroducing rigorous training in traditional drawing and painting techniques, employing teaching methodologies that were used in the École des Beaux-Arts. These schools pass on a method of instruction which melds formal academic art training with the influence of the French Impressionists.

Under the atelier model, art students study in the studio of an established master to learn how to draw and paint with realistic accuracy and an emphasis on rendering form convincingly. The foundation of these programs rests on an intensive study of the human figure, renderings of plaster casts of classical sculpture, and the emulation of their instructors. The goal is to make students adept at observation, theory, and craft while absorbing classical ideals of beauty.[9]

Atelier schools

[edit]Atelier schools founded in this tradition include (in chronological order of founding):

- Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, Krakow, Poland (1818)

- Laguna College of Art and Design, Laguna Beach, California (1961)

- Atelier Lack., Minneapolis, Minnesota, (1969)

- Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts, Old Lyme, Connecticut (1976)

- Charles H. Cecil Studios, Florence, Italy (1983)

- Gage Academy of Art, Seattle, Washington, (1989)

- The Florence Academy of Art, Florence, Italy and Jersey City, New Jersey (1991)

- Academy of Classical Design, Southern Pines, North Carolina, (2000)

- The Grand Central Atelier, Long Island City, New York (2006)

Notable artists

[edit]- William McGregor Paxton (1869-1941), painter

- R. H. Ives Gammell (1893-1981), painter, author

- Pietro Annigoni (1910–1988), painter

- Everett Raymond Kinstler (1926-2019), painter

- Richard F. Lack (1928-2009), painter, author

- Harvey Dinnerstein (1928-2022), painter

- Burton Silverman (born 1928), painter

- Richard Schmid (1934-2021), painter

- Samizu Matsuki (1936–2018), painter

- Nelson Shanks (1937–2015), painter

- Richard Whitney (born 1946), painter, author

- Ned Bittinger (born 1951), painter

- D. Jeffrey Mims (born 1954), painter

- Raymond Persinger (born 1959), sculptor

- Jacob Collins (born 1964), painter

- Igor Babailov (born 1965), painter

- Graydon Parrish (born 1970), painter

- Abbey Ryan (born 1979), painter

- Richard T. Scott (born 1980), painter

References

[edit]- ^ S. Birch, The Educational Times. Vol. 35, No. 249, January 1, 1882, page 294.

- ^ Mahler, Arthur; Blacker; Carlos; Slater, William Albert. Paintings of the Louvre, Italian and Spanish, Doubleday, 1905, page 26.

- ^ Jacobs, Ted Seth. Light for the Artist, Watson-Guptill Pubns (June 1988), ISBN 0-8230-2768-6.

- ^ Ryder, Anthony. The Artist's Complete Guide to Figure Drawing: A Contemporary Perspective on the Classical Tradition, Watson-Guptill; 1st edition (June 1, 1999), ISBN 0-8230-0303-5.

- ^ Gjertson, Stephen. Richard F. Lack: An American Master, American Society of Classical Realism: 2001, ISBN 0-9636180-3-2.

- ^ a b Panero, James (September 2006). "The New Old School". The New Criterion. Vol. 25. p. 104.

- ^ Kimball, Roger: "Why the Art World Is a Disaster", The New Criterion, Volume 25, June 2007, page 4.

- ^ Maureen Mullarkey (October 12, 2006). "Nothing Left To Hide". New York Sun. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Aristedes, Juliette. Classical Drawing Atelier: A Contemporary Guide to Traditional Studio Practice, Watson-Guptill Publications: 2006. ISBN 0-8230-0657-3

External links

[edit]- The Legacy of Richard Lack

- Slow Painting: A Deliberate Renaissance (Oglethorpe University Museum of Art, 2006)