Chinese Soviet Republic

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Chinese Soviet Republic 中華蘇維埃共和國 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1931–1937 | |||||||||||

| Motto: "Proletariats and oppressed peoples of the world, unite!"[n 1] | |||||||||||

| Anthem: "The Internationale"[n 2] | |||||||||||

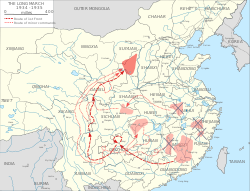

Map of the various soviets comprising the Chinese Soviet Republic and the route of the Long March | |||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||

| Largest city | Ruijin | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary Leninist one-party soviet socialist republic under a provisional government | ||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Executive Committee | |||||||||||

• 1931–1937 | Mao Zedong | ||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Revolutionary Military Committee | |||||||||||

• 1931–1937 | Zhu De | ||||||||||

| Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars | |||||||||||

• 1931–1934 | Mao Zedong | ||||||||||

• 1934–1937 | Zhang Wentian | ||||||||||

| Legislature | National Congress of the Chinese Soviets of Workers', Peasants' and Soldiers' Deputies | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||||

• Independence proclaimed from the Republic of China | 7 November 1931 | ||||||||||

• Start of the Long March | 7 October 1934 | ||||||||||

| 10 November 1934 | |||||||||||

• Arrival at Shaanxi | 22 October 1935 | ||||||||||

• Disintegration of the Soviet Republic | 22 September 1937 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Chinese Soviet yuan | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Chinese Soviet Republic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 中華蘇維埃共和國 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华苏维埃共和国 | ||||||||||

| Postal | Chunghwa Suwei'ai Kunghokuo | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Chinese Communist Revolution |

|---|

|

| Outline of the Chinese Civil War |

|

|

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR)[n 3] was a state within China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of the CSR included 18 provinces and 4 counties under the Communists' control. The CSR's government was located in its largest component territory, the Jiangxi Soviet. Due to the importance of the Jiangxi Soviet in the CSR's early history, the name "Jiangxi Soviet" is sometimes used to refer to the CSR as a whole.[8] Other component territories of the CSR included the Northeastern Jiangxi, Hunan-Jiangxi, Hunan-Hubei-Jiangxi, Hunan-Western Hubei, Hunan-Hubei-Sichuan-Guizhou, Eyuwan, Shaanxi-Gansu, Sichuan-Shanxi, and Haifeng-Lufeng Soviets.

Mao Zedong was both CSR state chairman and prime minister; he led the state and its government. Mao's tenure as head of a "small state within a state" gave him experience in mobile warfare and peasant organization, which helped him lead the Chinese Communists to victory in 1949.[9]

The Encirclement Campaigns launched by the Kuomintang in 1934 forced the CCP to abandon most of the soviets in southern China.[9] The CCP (including the leadership of the CSR) embarked on the Long March from southern China to the Yan'an Soviet, where a rump CSR continued to exist. A complex series of events in 1936 culminated in the Xi'an Incident, in which Chiang Kai-shek was kidnapped and forced to negotiate with the CCP. The CCP offered to abolish the CSR and put the Chinese Red Army under (nominal) Kuomintang command in exchange for autonomy and an alliance against Japan. These negotiations were successful, and eventually led to the creation of the Second United Front. The CSR was officially dissolved on 22 September 1937 and the Yan'an Soviet was officially reconstituted as the Shaan-Gan-Ning and Jin-Cha-Ji Border Regions.[10]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]During the First United Front between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang, the two parties embarked on the Northern Expedition in an effort to unify China under a single government.[11]: 35 In 1927, the KMT broke the United Front with the Shanghai Massacre and violently suppressed the Communists.[11]: 35 The Communists as well as a few army units loyal to them fled urban areas into the countryside, where they founded the Chinese Workers and Peasants' Red Army to wage civil war. A large group in southern China led by Mao Zedong established a base in the remote Jinggang Mountains.[12] A Kuomintang counterinsurgency campaign forced Mao and his group to relocate once again, and they moved into the border region between Jiangxi and Fujian provinces.[11]: 35

Meanwhile, Communists from other areas of China followed a similar pattern of retreat into the countryside. In order to rebuild the party's strength, the 6th National Congress ordered these rural cadres to organize soviet governments.[13] Beginning in 1929, soviets began to pop up in isolated regions across the country, including rural Guangxi, the Eyuwan border area, and the Xiangegan border area.[14][15] Mao's group founded the Jiangxi Soviet, which became the largest and best administered soviet thanks to the number of Communist cadres from across the country that took refuge there. Although the Central Committee of the Communist Party was still underground in Shanghai during this period, the center of political gravity had begun to shift to Mao in Jiangxi.[16]

Establishment and growth

[edit]In 1931, the Communist Party decided to consolidate these isolated base areas into a single state, the Chinese Soviet Republic.[11]: 1 On 7 November 1931 (the anniversary of the 1917 Russian October Revolution) a National Soviet People's Delegates Conference was held in Ruijin, the capital of the Jiangxi Soviet. The Conference held a formal opening ceremony for the CSR which included a military parade.[citation needed] Notably, communications between the far-flung soviets were so poor (due to their isolation and intense pressure from the Kuomintang) that the second-largest soviet, in Eyuwan, failed to send delegates. Instead, it held its own conference.[17][18]

With Mao Zedong as both head of state (Chinese: 中央執行委員會主席; lit. 'Chairman of the Central Executive Committee') and head of government (Chinese: 人民委員會主席; lit. 'Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars'), the CSR gradually expanded. The CSR reached its peak in 1933.[11]: 1 It governed a population which exceeded 3.4 million in an area of approximately 70,000 square kilometers (although the isolated soviets were never connected into one contiguous piece of territory).[11]: 1

Encirclement campaigns

[edit]The National Revolutionary Army conducted a series of campaigns against the various soviets of the CSR known as the "encirclement campaigns".[19] The Jiangxi Soviet survived the first, second and third encirclement campaigns thanks to the use of flexible guerrilla tactics. However, after the third counter-encirclement campaign Mao was replaced by Wang Ming, a Chinese communist returning from the Soviet Union. The Chinese Red Army was commanded by a three-man committee, which included Wang Ming's associates Otto Braun (a Comintern military advisor), Bo Gu and Zhou Enlai. The CSR then began a rapid decline, due to its extreme left-wing governance and incompetent military command. The new leadership could not rid itself of Mao's influence (which continued during the fourth encirclement campaign), which temporarily protected the communists. However, due to the dominance of the new communist leadership after the fourth counter-encirclement campaign, the Red Army was nearly halved. Most of its equipment was lost during Chiang's fifth encirclement campaign; this began in 1933 and was orchestrated by Chiang's newly-hired Nazi advisors who developed a strategy of building fortified blockhouses to advance the encirclement.[20]

This was effective; in an effort to break the blockade the Red Army besieged the forts many times, suffering heavy casualties and only limited success. As a result, the CSR shrank significantly due to the Chinese Red Army's manpower and material losses.[citation needed]

The Long March

[edit]Since the Jiangxi Soviet could not be held, the Standing Committee appointed Bo (responsible for politics), Braun (responsible for military strategy), and Zhou (responsible for the implementation of military planning) to organize an evacuation. The Communists managed to successfully hide their intentions from the besieging Nationalist forces for long enough to execute a successful breakout.[21] On October 16, 1934, a force of about 130,000 soldiers and civilians under Bo Gu and Otto Braun attacked the line of Kuomintang positions near Yudu. More than 86,000 troops, 11,000 administrative personnel and thousands of civilian porters actually completed the breakout; the remainder, largely wounded or ill soldiers, continued to fight a delaying action after the main force had left, and then dispersed into the countryside.[22] After passing through three of the four blockhouse fortifications needed to escape Chiang's encirclement, the Red Army was finally intercepted by regular Nationalist troops, and suffered heavy casualties. Of the 86,000 Communists who attempted to break out of Jiangxi with the First Red Army, only 36,000 successfully escaped. Due to the low morale within the Red Army at the time, it is not possible to know what proportion of these losses were due to military casualties, and which proportion were due to desertion. The conditions of the Red Army's forced withdrawal demoralized some Communist leaders (particularly Bo Gu and Otto Braun), but Zhou remained calm and retained his command.[23]

This retreat marked the beginning of what would become known as the Long March. During the course of the next two years, Communist forces abandoned almost all of their soviets in southern China that had made up the core of the CSR. The survivors went into hiding or followed Mao to Yan'an, where they took refuge in the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region.[24][25]

Dissolution

[edit]The Chinese Soviet Republic continued to exist formally even after the Long March, since the Communists still controlled some areas such as the Hubei-Henan-Shaanxi Soviet. Bao'an was, for a time, the capital until the Communist government was moved to the Yan'an Soviet. The Chinese Soviet Republic was dissolved on 22 September 1937 when the Chinese Communist Party issued, in the Second United Front, its manifesto on unity with the Kuomintang; the Second Sino-Japanese War was only a few weeks old.[26] The Chinese Communist Party remained in de facto control of Yan'an, which was its stronghold for the remainder of the war with Japan.

Administration

[edit]The CSR had a central government as well as local and regional governments.[11]: 1 It operated institutions including an education system and court system.[11]: 1 The CSR also issued currency.[11]: 1 It enacted the Constitutional Guideline of CSR in 1934.[27]

Land reform

[edit]The most important policy implemented by the soviet governments was land redistribution, which destroyed the landlord-dominated political economy which had existed previously.[11]: 2 The CSR issued the 1931 Land Law, which required:[11]: 37

All lands belonging feudal landlords, local bullies and evil gentry, warlords, bureaucrats, and other large private landlords, irrespective of whether they work the lands themselves or rent them out, shall be confiscated without compensation. The confiscated lands shall be redistributed to the poor and middle peasants through the [CSR]. The former owners of the confiscated lands shall not be entitled to receive any land allotments.

The property of rich peasants was also confiscated, although rich peasants were entitled to receive land of lesser quality if they farmed it themselves.[11]: 37 By 1932, the Communist Party had equalized landholding and eliminated debt within the CSR.[11]: 44 Although the 1931 Land Law remained the official policy in the CSR's territory until the Nationalists' defeat of the CSR in 1934,[11]: 37 after 1932, the Communist Party was more radical in its class analysis, resulting in formerly middle peasants being viewed as rich peasants.[11]: 44–46

The Chinese Red Army had modern communications technology (telephones, telegraph and radio, which the warlords' armies lacked), and transmitted wireless coded messages while breaking nationalist codes. At the time, only Chiang Kai-shek's army could match the communist forces.[citation needed]

The CSR declared itself a government of all Chinese workers, Red Army soldiers, and the masses.[11]: 38 CSR policy was in large part carried out by mass organizations, particularly the Poor Peasants League, which was composed entirely of poor peasants and farm laborers.[11]: 38 Poor peasants composed a majority of the membership of all CSR associations or state bodies.[11]: 38

The CSR issued regulations barring landlords, rich peasants, merchants, religious leaders, and Kuomintang members from participating in its elections.[11]: 38 Landlords and rich peasants were barred from joining the biggest civil organizations in the CSR, the Anti-Imperialist League and the Soviet Protection League.[11]: 38

Finance

[edit]On 1 February 1932, the Chinese Soviet Republic National Bank was established, with Mao Zemin as president. The CSR Central Mint issued three types of currency: a paper bill, a copper coin and a silver dollar.

The CSR was funded primarily by tax income on grain and rice.[11]: 48 It also received voluntary contributions from its core political constituency, the peasantry.[11]: 48 During the period 1931 to 1934, the CSR issued three series of government bonds to further finance its operations.[11]: 47

Banknotes

[edit]

The Central Mint briefly issued both paper bills and copper coins. Neither circulated for long, primarily because the currency could not be used in the rest of China. The paper bill had "Chinese Soviet Republic National Bank" (中華蘇維埃共和國國家銀行) printed on the bill in traditional Chinese characters and a picture of Vladimir Lenin.

Copper coins

[edit]Like the paper bill, copper coins issued by the Central Mint also had "Chinese Soviet Republic" (中華蘇維埃共和國) engraved in traditional Chinese. Since coins last longer than paper bills, these coins were issued (and circulated) in a much greater quantity. However, these coins are rarer than the paper bill; copper was needed for ammunition, and these copper coins were recalled and replaced by silver dollars.

Silver dollars

[edit]The predominant currency produced by the Central Mint was the silver dollar. Unlike the bills and copper coins, the silver dollars had no communist symbols; they were a copy of silver dollars produced by other mints in China (including the popular coin with the head of Yuan Shikai and the eagle silver dollar of the Mexican peso). This, and the fact that the coin was made of silver, enabled them to be circulated in the rest of China; thus, it was the currency of choice.

When the Chinese Red Army's First Front began its Long March in October 1934, the Communist bank was part of the retreating force; fourteen bank employees, over a hundred coolies and a company of soldiers escorted them with the money and mint machinery. An important duty of the bank was, when the Chinese Red Army stayed in a location for longer than a day, to have the local populace exchange Communist paper bills and copper coins for currency used in the nationalist-controlled regions to avoid prosecution by the nationalists after the Communists left. The Zunyi Conference decided that carrying the entire bank on the march was impractical, and on 29 January 1935, at Tucheng (土城) the bank employees burned all Communist paper bills and destroyed the mint machinery. By the end of the Long March in October 1935, only eight of the original fourteen employees were left; the other six had died along the way.

Taxation

[edit]In November 1931, the National Tax Bureau was founded. In 2002, the original building was renovated for the public.

Postage stamps

[edit]The Directorate General of Chinese Soviet Posts was founded in Ruijin on 1 May 1932.[28] The first stamps were designed by Huang Yaguang and printed lithographically by the Printing House of the Ministry of Finance in Ruijin. White paper or newspaper was used. They were imperforate, and denominated in the Chinese Soviet silver-dollar currency. They are fairly rare, and sought after by collectors. There are also many forgeries and bogus issues imitating early stamps from the Communist areas.

Intelligence

[edit]Zhou Enlai had planted more than a dozen moles in Chiang Kai-shek's inner circle, including his general headquarters at Nanchang. One of Zhou's most important agents, Mo Xiong, was not a communist; however, his contributions saved the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Red Army.

With recommendations from Chiang Kai-shek's secretary-general Yang Yongtai (who was unaware of Mo's Communist activities), Mo rose in Chiang Kai-shek's regime and became an important member in his general headquarters during the early 1930s. In January 1934, Chiang Kai-shek appointed him administrator and commander-in-chief of the Fourth Special District in northern Jiangxi. Mo used his position to plant more than a dozen Communist agents in Chiang's general headquarters, including Liu Yafo (劉亞佛) (who introduced the Chinese Communist Party), Xiang Yunian (項與年) (his Communist handler, whom he hired as his secretary) and Lu Zhiying (acting head of the spy ring, under the command of Zhou Enlai).

After successfully besieging the Ruijin area (the CSR capital) and occupying most of the CSR itself, Chiang was confident that he could defeat the Communists in a final decisive strike. In late September 1934 he distributed his top-secret "Iron Bucket Plan" to general headquarters at Lushan (the summer substitute for Nanchang), which detailed the final push to annihilate the Communist forces. Chiang planned 30 blockade lines supported by 30 barbed wire fences (most electrified) in a 150-kilometre (93 mi) radius around Ruijin to starve the Communists. In addition, more than 1,000 trucks were to be mobilized in a rapid-reaction force to prevent a Communist breakout. Realizing the certainty of Communist annihilation, Mo Xiong handed the several-kilogram document to Xiang Yunian (項與年) the same night—risking his life and those of his family.

With help from Liu Yafo (劉亞佛) and Lu Zhiying, Communist agents copied the intelligence into four dictionaries and Xiang Yunian (項與年) was tasked with bringing it to the CSR. The trip was hazardous, since the nationalist forces arrested and executed anyone attempting to cross the blockade. Xiang Yunian (項與年) hid in the mountains, knocking out four of his teeth with a rock and causing his face to swell. Disguised as a beggar, he tore off the covers of the four dictionaries and covered them with spoiled food at the bottom of his bag. Crossing several blockade lines, he reached Ruijin on 7 October 1934. The intelligence provided by Mo Xiong convinced the Communists in the CSR to abandon their base and retreat before Chiang could reinforce his blockade lines with barbed-wire fences. They mobilized trucks and troops, saving themselves from annihilation.

Historiography

[edit]The official history in the People's Republic of China views the Chinese Soviet Republic positively, although it is recognized that the regime was ultimately a failure. In a speech on the 80th anniversary of the CSR's founding, Xi Jinping focused on the fact that the CSR was attempting to do something novel, stating "The Chinese Soviet Republic was the first national workers' and peasants' regime in Chinese history."[29][30][31] The efforts of the CSR government are seen as having built the reputation of the CCP and strengthened the Chinese Red Army. Commentaries usually tout the CSR as an experiment that paved the way for the success of the later People's Republic.[32] In the Historical Picture Book of the Chinese Soviet Republic, the Ganzhou Municipal Committee of the CCP called the CSR a "great rehearsal for the People's Republic of China."[33]

See also

[edit]- Outline of the Chinese Civil War

- Communist-controlled China (1927–1949)

- Two Chinas

- Chinese Red Army

- National Revolutionary Army

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Politics of the People's Republic of China

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Yang & Chen 2019.

- ^ Smith 1975.

- ^ Cui 2003.

- ^ Communist Party of China (1997–2006). 中國國歌百年演變史話. Communist Party of China News (in Chinese). Communist Party of China. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Founding of the temporary central government of the Chinese Soviet Republic". China Military Online. People's Liberation Army.

- ^ "Announcement of the Interim Government of the China Soviet Republic (No. 1)". National Museum of China. Government of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Address by Foreign Minister George K.C. Yeh/Statement by Dr. C.L. Hsia on Land Reform in Taiwan before the Second Committee of the UN General Assembly, Nov. 12, 1954". Taiwan Today. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). 1 April 1955.

- ^ Waller, Derek J. (1973). The Kiangsi Soviet Republic: Mao and the National Congresses of 1931 and 1934. Center for Chinese Studies, University of California.

- ^ a b "Chinese Soviet Republic". Cultural China. cultural-china.com. 2007–2010. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ "The Yan'an Soviet". 18 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Opper, Marc (2020). People's Wars in China, Malaya, and Vietnam. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.11413902. hdl:20.500.12657/23824. ISBN 978-0-472-90125-8. JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.11413902. S2CID 211359950.

- ^ Carter 1976, p. 64; Schram 1966, pp. 122–125; Feigon 2002, pp. 46–47

- ^ Averill 1987, p. 289.

- ^ Benton 1992, p. 312.

- ^ Goodman 1994, p. 31.

- ^ Benton 1992, p. 311.

- ^ Phillips 1996, p. 109.

- ^ Benton 1992, p. 307.

- ^ Military History Research Department (2000). "Overview of Campaigns and Battles Fought by the People's Liberation Army (中国人民解放军战役战斗总览)". 中国人民解放军全史 [The Complete History of the People's Liberation Army]. Beijing: Military Science Publishing House. ISBN 7801373154.

- ^ Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the Twentieth-Century World: a Concise History. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- ^ Barnouin & Yu 2006, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Mao Zedong, On Tactics...: Note 26 retrieved 2007-02-17

- ^ Barnouin & Yu 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Barnouin, Barbara and Yu Changgen. Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2006. ISBN 962-996-280-2. Retrieved March 12, 2011. p.61

- ^ Chang, Jung (2005). Mao: The Unknown Story. Alfred A. Knoff.

- ^ Lyman P. Van Slyke, The Chinese Communist movement: a report of the United States War Department, July 1945, Stanford University Press, 1968, p. 44.

- ^ Fang, Qiang (2024). "Understanding the "Rule of Law" in Xi's China". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.). China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment. Leiden University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9789087284411.

- ^ The Postage Stamp Catalogue of the Chinese People's Revolutionary Period, published by Chinese Postage Stamp Museum.

- ^ "在纪念中央革命根据地创建暨中华苏维埃共和国成立80周年座谈会上的讲话(2011年11月4日)". People's Daily. 5 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "纪念中央革命根据地创建暨中华苏维埃共和国成立80周年座谈会在京举行 习近平出席并讲话". Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "在纪念中央革命根据地创建暨中华苏维埃共和国成立80周年座谈会上的讲话(2011年11月4日)". Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "走向胜利之本——从红都到首都的启示". People's Daily. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "《中华苏维埃共和国历史画册》". Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

The Chinese Soviet Republic is the first of a new type of state in Chinese history, founded under the leadership of the Communist Party of China with a dictatorship of the proletariat. This experimental regime can be said to have been a great rehearsal for the People's Republic of China... The Chinese Soviet Republic was the precursor of today's People's Republic of China, and so was the cradle of the Republic.

Sources

[edit]- Barnouin, Barbara; Yu, Changgen (2006). Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. ISBN 962-996-280-2.

- Averill, Stephen (May 1987). "Party, Society, and Local Elite in the Jiangxi Communist Movement". The Journal of Asian Studies. 46 (2): 279–303. doi:10.2307/2056015. JSTOR 2056015.

- Benton, Gregor (1992). Mountain Fires: The Red Army's Three-year War in South China, 1934-1938. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Cui, Yanxun, ed. (2003). "Chinese". Atlas of Flags in China. Beijing: China Peace Publishing House. pp. 105–106.

- Carter, Peter (1976). Mao. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192731401.

- Feigon, Lee (2002). Mao: A Reinterpretation. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1566634588.

- Schram, Stuart (March 2007). "Mao: The Unknown Story". The China Quarterly (189): 205. doi:10.1017/s030574100600107x. S2CID 154814055.

- Goodman, David (1994). Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-83121-0.

- Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags through the Ages and Across the World. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 110–112. ISBN 9780070590939. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Yang, Pinping; Chen, Tong (9 September 2019). "From the flag of the Chinese Soviet Republic to the five-star red flag Ruijin: The People's Republic came from here". XHBY.net (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Phillips, Richard T. (1996). China Since 1911. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Schram, Stuart (1966). Mao Tse-Tung. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0140208405.

- Yang Stamp Catalogue of The People's Republic of China (Liberated Area) Nai-Chiang Yang, 1998, 7th edition.

External links

[edit]- Preface to Fundamental Laws of the Chinese Soviet Republic

- Coins of the Szechuan-Shensi Soviet

- Coins (archived 28 August 2008)

- 12 stamps (explanatory caption in Simplified Chinese) (archived 26 June 2003)

- Jiangxi

- Chinese Soviet Republic

- 1931 establishments in China

- 1937 disestablishments in China

- Chinese Civil War

- Former socialist republics

- Former countries in Chinese history

- States and territories established in 1931

- Soviet republics

- Former countries of the interwar period

- East China

- States and territories disestablished in 1937