Shanghai massacre

| Shanghai massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

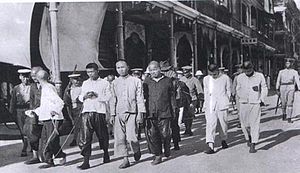

Communists being rounded up during the purges | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Green Gang |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

(NRA commander-in-chief) (NRA commander in Shanghai) Du Yuesheng (Green Gang leader) |

(CCP general secretary) | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Approx. 5,000 soldiers of the 2nd Division of the 26th Army and members of various gangs | Thousands from labor union militias | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minimal | 5,000[1]–10,000[2] killed | ||||||

| Shanghai massacre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 四一二事件 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 四一二清黨 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 四一二清党 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(2) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 東南清黨 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 东南清党 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(3) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 四一二反革命政變 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 四一二反革命政变 | ||

| |||

| Alternative name(4) | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 四一二慘案 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 四一二惨案 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on the |

| Chinese Communist Revolution |

|---|

|

| Outline of the Chinese Civil War |

|

|

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supporting General Chiang Kai-shek and conservative factions in the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party or KMT). Following the incident, conservative KMT elements carried out a full-scale purge of communists in all areas under their control, and violent suppression occurred in Guangzhou and Changsha.[3] The purge led to an open split between left-wing and right-wing factions in the KMT, with Chiang Kai-shek establishing himself as the leader of the right-wing faction based in Nanjing, in opposition to the original left-wing KMT government based in Wuhan, which was led by Wang Jingwei. By 15 July 1927, the Wuhan regime had expelled the Communists in its ranks, effectively ending the First United Front, a working alliance of both the KMT and CCP under the tutelage of Comintern agents. For the rest of 1927, the CCP would fight to regain power, beginning the Autumn Harvest Uprising. With the failure and the crushing of the Guangzhou Uprising at Guangzhou however, the power of the Communists was largely diminished, unable to launch another major urban offensive.[4]

Names

[edit]In KMT historiography, the event is occasionally referred to as the April 12 Purge (simplified Chinese: 四一二清党; traditional Chinese: 四一二清黨; pinyin: Sìyī'èr Qīng Dǎng; Wade–Giles: Ssu4-i1-erh4 Ch'ing1 Tang3), while Communist historiography refers to the event as either the April 12 Counter-revolutionary Coup (simplified Chinese: 四一二反革命政变; traditional Chinese: 四一二反革命政變; pinyin: Sìyī'èr Fǎngémìng Zhèngbiàn; Wade–Giles: Ssu4-i1-erh4 Fan3-ko2-ming4 Cheng4-pien4) or the April 12 Massacre (Chinese: 四一二慘案; pinyin: Sìyī'èr Cǎn'àn; Wade–Giles: Ssu4-i1-erh4 Ts'an3-an4).[5]

Background

[edit]The roots of the April 12 Incident go back to the Kuomintang's alliance with the Soviet Union, formally initiated by the KMT founder Sun Yat-sen after discussions with Soviet diplomat Adolph Joffe in January 1923. The alliance included both financial and military aid and a small but important group of Soviet political and military advisors, headed by Mikhail Borodin.[6] The Soviet Union's conditions for alliance and aid included co-operation with the small Chinese Communist Party. Sun agreed to let the Communists join the KMT as individuals but ruled out an alliance with them or their participation as an organized bloc. In addition, he demanded that the Communists, upon joining the KMT, adhere to KMT ideology and observe party discipline. Following their admission to the KMT, Communist activities, often covert, soon attracted opposition to the alliance among prominent KMT members.[7] Internal conflicts between left- and right-wing leaders of the KMT with regards to the United Front with the CCP continued right up to the launch of the Northern Expedition.

Plans for a Northern Expedition originated with Sun Yat-sen. After his expulsion from the government in Peking, he had by 1920 made a military comeback and gained control of some parts of Guangdong province. His goal was to extend his control over all of China, particularly Peking. After Sun's death from cancer in March 1925, KMT leaders continued to push the plan, and after they had purged Guangzhou's Communists and Soviet advisors during the "Canton Coup" on 20 May 1926, they finally launched the Expedition that June. Initial successes in the first months of the Expedition soon saw the KMT National Revolutionary Army (NRA) in control of Guangdong and large areas in Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi and Fujian.

With the growth of KMT authority and military strength, the struggle for control of the Party's direction and leadership intensified. In January 1927, the NRA, commanded by Chiang Kai-shek captured Wuhan and went on to attack Nanchang, and KMT leader Wang Jingwei and his left-wing allies, along with the Chinese Communists and the Soviet agent Borodin, transferred the seat of the Nationalist Government from Guangzhou to Wuhan. On 1 March, the Nationalist government reorganized the Military Commission and placed Chiang under its jurisdiction while it secretly plotted to arrest him. Chiang found out about the plot, which most likely led to his determination to purge the CCP from the KMT.[8]

In response to the advances of the NRA, Communists in Shanghai began to plan uprisings against the warlord forces controlling the city. On 21–22 March, KMT and CCP union workers, led by Zhou Enlai and Chen Duxiu, launched an armed uprising in Shanghai and defeated the warlord forces of the Zhili clique. The victorious union workers occupied and governed urban Shanghai except for the international settlements prior to the arrival of the NRA's Eastern Route Army, led by Generals Bai Chongxi and Li Zongren. After the Nanking Incident in which foreign concessions in Nanjing were attacked and looted, both the right wing of the Kuomintang and Western powers became alarmed by the growth of the influence of the Communists, who continued to organize daily mass student protests and labor strikes to demand the return of Shanghai international settlements to Chinese control.[9] With Bai's army firmly in control of Shanghai, on 2 April the Central Control Commission of KMT, led by former Chancellor of Peking University Cai Yuanpei, determined that the CCP actions were anti-revolutionary and undermined the national interest of China, and it voted unanimously to purge the Communists from the KMT.[10][better source needed]

Purge

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

On 5 April, Wang Jingwei arrived in Shanghai from overseas and met with the CCP leader Chen Duxiu. After their meeting they issued a joint declaration re-affirming the principle of cooperation between the KMT and the CCP, despite urgent pleas from Chiang and other KMT elders to eliminate Communist influence. When Wang left Shanghai for Wuhan the next day, Chiang asked Green Gang leader Du Yuesheng and other gang leaders in Shanghai to form a rival union to oppose the Shanghai labor union controlled by the Communists, and made final preparations for purging CCP members.

On 9 April, Chiang declared martial law in Shanghai and the Central Control Commission issued the "Party Protection and National Salvation" proclamation (simplified Chinese: 保党救国; traditional Chinese: 保黨救國; pinyin: Bǎo dǎng jiùguó; Wade–Giles: Pao3 tang3 chiu4-kuo2), denouncing the Wuhan Nationalist Government's policy of cooperation with the CCP. On 11 April, Chiang issued a secret order to all provinces under the control of his forces to purge Communists from the KMT.

Before dawn on 12 April, gang members began to attack district offices controlled by the union workers, including Zhabei, Nanshi, and Pudong. Under an emergency decree, Chiang ordered the 26th Army to disarm the workers' militias; that resulted in more than 300 people being killed and wounded. The union workers organized a mass meeting denouncing Chiang Kai-shek on 13 April, and thousands of workers and students went to the headquarters of the 2nd Division of the 26th Army to protest. Soldiers opened fire, killing 100 and wounding many more. Chiang dissolved the provisional government of Shanghai, labor unions and all other organizations under Communist control, and reorganized a network of unions with allegiance to the Kuomintang and under the control of Du Yuesheng. Some sources say that over 1,000 Communists and KMT leftists[11] were arrested, some 300 were executed and more than 5,000 went missing; some state that 5,000 Communists and leftists were killed[1] while others claim up to 10,000 were killed.[2] Western news reports later nicknamed Gen. Bai "The Hewer of Communist Heads".[12] Some National Revolutionary Army commanders with Communist backgrounds who were graduates of Whampoa Military Academy kept their sympathies for the Communists hidden and were not arrested, and many switched their allegiance to the CCP after the start of the Chinese Civil War.[13]

During the White Terror, local Kuomintang officials specifically targeted short-haired women who had not been subjected to foot binding. These officials presumed that women who rejected foot binding and traditional hair styles were radicals. Kuomintang forces would cut off their breasts and shave their heads, displaying their mutilated corpses to cow the populace.[14]

Aftermath and significance

[edit]

During the White Terror, the Kuomintang killed more than one million people, primarily peasants.[14] More than 10,000 communists were executed in Changsha within 20 days. The Soviet Union officially terminated its cooperation with the KMT while Wang, fearing retribution as a Communist sympathizer, fled to Europe. The Wuhan Nationalist government soon disintegrated, leaving Chiang as the sole legitimate leader of the Kuomintang. In the years after April 1927, 300,000 people were killed in Hunan in three years of warfare against the Communists while many Hakkas and She people's whole families killed in the mountains, including infants, while young women were sold to prostitution.[15][16] About 80,000 people were killed in Hunan's Liling and about 300,000 Hunanese civilians were killed in Hunan's Chaling County, Leiyang, Liuyang and Pingjiang.[17]

For the Kuomintang, 39 members of the Kuomintang Central Committee in Wuhan publicly denounced Chiang Kai-shek as a traitor to Sun Yat-sen, including Sun's widow Soong Ching-ling immediately after the purge. However, Chiang was defiant, forming a brand new Nationalist Government to rival the Communist-tolerant Nationalist Government in Wuhan controlled by Wang Jingwei on 18 April. The purges garnered the Nanjing government the support of much of the NRA, the Chinese merchant class, and foreign businesses, bolstering its economic and military position.[18]

The twin rival KMT governments, known as the Ninghan[a] Split (simplified Chinese: 宁汉分裂; traditional Chinese: 寧漢分裂; pinyin: Nínghàn Fēnliè; Wade–Giles: Ning2-han4 Fen1-lie4), did not last long. In May 1927, Communists and peasant leaders in the Wuhan area were repeatedly attacked by Nationalist generals.[19] On 1 June, Joseph Stalin sent a telegram to the Communists in Wuhan, calling for mobilisation of an army of workers and peasants.[20] This alarmed Wang Jingwei, who decided to break with the Communists and come to terms with Chiang Kai-shek.

On the Communists' side, Chen Duxiu and his Soviet advisers, who had promoted cooperation with the KMT, were discredited and lost their leadership roles in the CCP. Chen was personally blamed, forced to resign and replaced by Qu Qiubai, who did not change Chen's policies in any fundamental way. The CCP planned for worker uprisings and revolutions in the urban areas.[15] The White Terror completely routed the Communists, and only 10,000 party members out of 60,000 survived.[14]

The first battles of the ten-year Chinese Civil War began with armed Communist insurrections in Changsha, Nanchang, and Guangzhou. During the Nanchang Uprising in August, Communist troops under Zhu De were defeated but escaped from Kuomintang forces by withdrawing to the mountains of Jiangxi. In September Mao led a small peasant army in the Autumn Harvest Uprising in Hunan. It was brutally crushed and the survivors retreated to Jiangxi as well, forming the first elements of what would become the People's Liberation Army. By the time the CCP Central Committee was forced to flee Shanghai in 1933, Mao had established peasant-based soviets in Jiangxi and Hunan provinces, turning the Communist's base of support from urban proletariat to the countryside, where the People's War would be fought.

In June 1928, the National Revolutionary Army captured the Beiyang government's capital of Beijing, leading to the nominal unification of China and worldwide recognition of the Republic as the legal government of China.[21]

See also

[edit]- Outline of the Chinese Civil War

- First United Front

- History of the Republic of China

- Republic of China Armed Forces

- List of massacres in China

- Guangzhou Uprising

- Shanghai Commune of 1927

- Shanghai People's Commune

- Man's Fate, a 1933 novel written by André Malraux

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A portmanteau of Nanjing and Wuhan

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Carter, Peter (1976). Mao. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0192731401.

In the next weeks five thousand Communists were butchered by the stammering machine-guns of the Kuomintang and by the knives of the criminal gangs whom Chiang recruited for slaughter.

- ^ a b Ryan, Tom (2016). Purnell, Ingrid; Plozza, Shivaun (eds.). China Rising: The Revolutionary Experience. Collingwood: History Teachers' Association of Victoria. p. 77. ISBN 9781875585083.

- ^ Wilbur 1983, p. 114.

- ^ Wilbur 1983, p. 170.

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng (8 September 2004). A Nation-State by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism (1st ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804750011.

- ^ Wilbur 1976, pp. 135–140.

- ^ Wilbur 1976, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Chang, Kuo-t'ao (1972). The rise of the Chinese Communist Party: 1928–1938. University Press of Kansas. p. 581. ISBN 9780700600724.

- ^ J. Perry, Elizabeth (11 April 2003). "Revolution Betrayed? The Fate of Revolutionary Militias in China (and Other Post-revolutionary Societies)". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Archived from the original on 1 June 2004. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ Chen Lifu, "Columbia Interviews", part 1, p. 29.

- ^ "許劍虹觀點:國共是如何分家的?談談95年前蔣中正與馮玉祥的會面-風傳媒" [Xu Jianhong’s point of view: How did the Kuomintang and the Communist Party separate? Talk about the meeting between Chiang Kai-shek and Feng Yuxiang 95 years ago]. storm.mg (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 19 June 2022. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "China: Nationalist Notes". Time. 25 June 1928. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Chang, Jung; Halliday, Jon (2005). Mao, The Unknown Story. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-224-07126-2.

- ^ a b c Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the Twentieth-Century World: A Concise History. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ a b Barnouin, Barbara; Changgen, Yu (2006). Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9789629962807.

- ^ Constable, Nicole (2014). Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295805450.

- ^ Short, Philip (2016). Mao: The Man Who Made China. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781786730152.

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. (2013). China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894–1949. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-1782004073.

- ^ Harrison 1972, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Harrison 1972, p. 111.

- ^ Stranahan, Patricia (July 1994). "The Politics of Persuasion: Communist Rhetoric and the Revolution". Indiana University Bloomington. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chan, F. Gilbert; H. Etzold, Thomas (1976). China in the 1920s: Nationalism and Revolution. New York: New Viewpoints. ISBN 978-0-531-05589-2.

- Chesneaux, Jean (1968). The Chinese Labor Movement 1919–1927. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804706445.

- Harrison, James P. (1972). The Long March to Power – a History of the Chinese Communist Party, 1921–72. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0333141547.

- Isaacs, Harold; Trotsky, Leon (1 May 2010). Issacs, Arnold (ed.). The Tragedy of The Chinese Revolution (reprinted ed.). Chicago: Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-931859-84-4.

- Perry, Elizabeth J. (1995). Shanghai on Strike: The Politics of Chinese Labor. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2491-3.

- Smith, Stephen A. (2000). A Road Is Made: Communism in Shanghai, 1920-1927. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2314-6.

- Stranahan, Patricia (1998). Underground: The Shanghai Communist Party and the Politics of Survival, 1927–1937. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-8476-8723-6.

- Wilbur, C. Martin (1976). Sun Yat-Sen, Frustrated Patriot. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231040365.

- Wilbur, C. Martin (1983). The Nationalist Revolution in China, 1923–1928. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31864-8.

- Wilbur, C. Martin; Lien-ying How, Julie (1989). Missionaries of Revolution: Soviet Advisers and Nationalist China, 1920-1927. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-57652-0.

External links

[edit]- Exploring Chinese History: The Nationalist Movement

- Tales of Old Shanghai: 1927 – the Communist Purge Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Chinese Civil War

- 1927 in China

- Massacres in 1927

- Anti-communism in China

- Anti-communist terrorism

- China–Soviet Union relations

- Conflicts in 1927

- People murdered by organized crime

- Organized crime conflicts

- Triad (organized crime)

- Massacres in China

- Political repression in the Republic of China

- Political and cultural purges

- White Terror

- Chinese Communist Party

- 1927 in Shanghai

- 20th-century mass murder in China

- April 1927 events

- Northern Expedition

- 1927 murders in China

- Massacres committed by China

- Chinese Communist Revolution

- Military history of Shanghai

- Politicides

- Executed communists