Internet censorship

| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

Internet censorship is the legal control or suppression of what can be accessed, published, or viewed on the Internet. Censorship is most often applied to specific internet domains (such as Wikipedia.org, for example) but exceptionally may extend to all Internet resources located outside the jurisdiction of the censoring state. Internet censorship may also put restrictions on what information can be made internet accessible.[1] Organizations providing internet access – such as schools and libraries – may choose to preclude access to material that they consider undesirable, offensive, age-inappropriate or even illegal, and regard this as ethical behavior rather than censorship. Individuals and organizations may engage in self-censorship of material they publish, for moral, religious, or business reasons, to conform to societal norms, political views, due to intimidation, or out of fear of legal or other consequences.[2][3]

The extent of Internet censorship varies on a country-to-country basis. While some countries have moderate Internet censorship, other countries go as far as to limit the access of information such as news and suppress and silence discussion among citizens.[3] Internet censorship also occurs in response to or in anticipation of events such as elections, protests, and riots. An example is the increased censorship due to the events of the Arab Spring. Other types of censorship include the use of copyrights, defamation, harassment, and various obscene material claims as a way to deliberately suppress content.

Support for and opposition to Internet censorship also varies. In a 2012 Internet Society survey, 71% of respondents agreed that "censorship should exist in some form on the Internet". In the same survey, 83% agreed that "access to the Internet should be considered a basic human right" and 86% agreed that "freedom of expression should be guaranteed on the Internet". Perception of internet censorship in the US is largely based on the First Amendment and the right for expansive free speech and access to content without regard to the consequences.[4] According to GlobalWebIndex, over 400 million people use virtual private networks to circumvent censorship or for increased user privacy.[5]

Overview

[edit]Many of the challenges associated with Internet censorship are similar to those for offline censorship of more traditional media such as newspapers, magazines, books, music, radio, television, and film. One difference is that national borders are more permeable online: residents of a country that bans certain information can find it on websites hosted outside the country. Thus censors must work to prevent access to information even though they lack physical or legal control over the websites themselves. This in turn requires the use of technical censorship methods that are unique to the Internet, such as site blocking and content filtering.[6]

Views about the feasibility and effectiveness of Internet censorship have evolved in parallel with the development of the Internet and censorship technologies:

- A 1993 Time Magazine article quotes computer scientist John Gilmore, one of the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, as saying "The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it."[7]

- In November 2007, "Father of the Internet" Vint Cerf stated that he sees government control of the Internet failing because the Web is almost entirely privately owned.[8]

- A report of research conducted in 2007 and published in 2009 by the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University stated that: "We are confident that the [censorship circumvention] tool developers will for the most part keep ahead of the governments' blocking efforts", but also that "...we believe that less than two percent of all filtered Internet users use circumvention tools."[9]

- In contrast, a 2011 report by researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute published by UNESCO concludes "... the control of information on the Internet and Web is certainly feasible, and technological advances do not therefore guarantee greater freedom of speech."[6]

Blocking and filtering can be based on relatively static blacklists or be determined more dynamically based on a real-time examination of the information being exchanged. Blacklists may be produced manually or automatically and are often not available to non-customers of the blocking software. Blocking or filtering can be done at a centralized national level, at a decentralized sub-national level, or at an institutional level, e.g., in libraries, universities or Internet cafés.[3] Blocking and filtering may also vary within a country across different ISPs.[10] Countries may filter sensitive content on an ongoing basis and/or introduce temporary filtering during key time periods such as elections. In some cases, the censoring authorities may surreptitiously block content to mislead the public into believing that censorship has not been applied. This is achieved by returning a fake "Not Found" error message when an attempt is made to access a blocked website.[11]

Unless the censor has total control over all Internet-connected computers, such as in North Korea (who employs an intranet that only privileged citizens can access), or Cuba, total censorship of information is very difficult or impossible to achieve due to the underlying distributed technology of the Internet. Pseudonymity and data havens (such as Hyphanet) protect free speech using technologies that guarantee material cannot be removed and prevents the identification of authors. Technologically savvy users can often find ways to access blocked content. Nevertheless, blocking remains an effective means of limiting access to sensitive information for most users when censors, such as those in China, are able to devote significant resources to building and maintaining a comprehensive censorship system.[6]

The term "splinternet" is sometimes used to describe the effects of national firewalls. The verb "rivercrab" colloquially refers to censorship of the Internet, particularly in Asia.[12]

Content suppression methods

[edit]Technical censorship

[edit]Various parties are using different technical methods of preventing public access to undesirable resources, with varying levels of effectiveness, costs and side effects.

Blacklist

[edit]Entities mandating and implementing the censorship usually identify them by one of the following items: keywords, domain names and IP addresses. Lists are populated from different sources, ranging from private supplier through courts to specialized government agencies (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China, Islamic Guidance in Iran).[13]

As per Hoffmann, different methods are used to block certain websites or pages including DNS spoofing, blocking access to IPs, analyzing and filtering URLs, inspecting filter packets and resetting connections.[14]

Points of control

[edit]Enforcement of the censor-nominated technologies can be applied at various levels of countries and Internet infrastructure:[13]

- Internet backbone, including Internet exchange points (IXP) with international networks (Autonomous Systems), operators of submarine communications cables, satellite Internet access points, international optical fibre links etc. In addition to facing huge performance challenges due to large bandwidths involved, these do not give censors access to information exchanged within the country.

- Internet Service Providers, which involves installation of voluntary (such as in the UK) or mandatory (such as in Russia) Internet surveillance and blocking equipment.

- Individual institutions, which in most cases implement some form of Internet access controls to enforce their own policies, but, especially in case of public or educational institutions, may be requested or coerced to do this on the request from the government.

- Personal devices, whose manufacturers or vendors may be required by law to install censorship software.

- Application service providers (e.g. social media companies), who may be legally required to remove particular content. Foreign providers with business presence in given country may be also coerced into restricting access to specific contents for visitors from the requesting country.

- Certificate authorities may be required to issue counterfeit X.509 certificates controlled by the government, allowing man-in-the-middle surveillance of TLS encrypted connections.

- Content Delivery Network providers who tend to aggregate large amounts of content (e.g. images) may be also an attractive target for censorship authorities.

Approaches

[edit]Internet content is subject to technical censorship methods, including:[3][6]

- Internet Protocol (IP) address blocking: Access to a certain IP address is denied. If the target Web site is hosted in a shared hosting server, all websites on the same server will be blocked. This affects IP-based protocols such as HTTP, FTP and POP. A typical circumvention method is to find proxies that have access to the target websites, but proxies may be jammed or blocked, and some Web sites, such as Wikipedia (when editing), also block proxies. Some large websites such as Google have allocated additional IP addresses to circumvent the block, but later the block was extended to cover the new addresses[citation needed]. Due to challenges with geopositioning, geo-blocking is normally implemented via IP address blocking.

- Domain name system (DNS) filtering and redirection: Connections to blocked domain names are not resolved, or an incorrect IP address is returned via DNS hijacking or other means. This affects all IP-based protocols such as HTTP, FTP and POP. A typical circumvention method is to find an alternative DNS resolver that resolves domain names correctly, but domain name servers are subject to blockage as well, especially IP address blocking. Another workaround is to bypass DNS if the IP address is obtainable from other sources and is not itself blocked. Examples are modifying the Hosts file or typing the IP address instead of the domain name as part of a URL given to a Web browser.

- Uniform Resource Locator (URL) filtering: URL strings are scanned for target keywords regardless of the domain name specified in the URL. This affects the HTTP protocol. Typical circumvention methods are to use escaped characters in the URL, or to use encrypted protocols such as VPN and TLS/SSL.[15]

- Packet filtering: Terminate TCP packet transmissions when a certain number of controversial keywords are detected. This affects all TCP-based protocols such as HTTP, FTP and POP, but Search engine results pages are more likely to be censored. Typical circumvention methods are to use encrypted connections – such as VPN and TLS/SSL – to escape the HTML content, or by reducing the TCP/IP stack's MTU/MSS to reduce the amount of text contained in a given packet.

- Connection reset: If a previous TCP connection is blocked by the filter, future connection attempts from both sides can also be blocked for some variable amount of time. Depending on the location of the block, other users or websites may also be blocked, if the communication is routed through the blocking location. A circumvention method is to ignore the reset packet sent by the firewall.[16]

- Network disconnection: A technically simpler method of Internet censorship is to completely cut off all routers, either by software or by hardware (turning off machines, pulling out cables). A circumvention method could be to use a satellite ISP to access Internet.[17]

- Portal censorship and search result removal: Major portals, including search engines, may exclude web sites that they would ordinarily include. This renders a site invisible to people who do not know where to find it. When a major portal does this, it has a similar effect to censorship. Sometimes this exclusion is done to satisfy a legal or other requirement, other times it is purely at the discretion of the portal. For example, Google.de and Google.fr remove Neo-Nazi and other listings in compliance with German and French law.[18]

- Computer network attacks: Denial-of-service attacks and attacks that deface opposition websites can produce the same result as other blocking techniques, preventing or limiting access to certain websites or other online services, although only for a limited period of time. This technique might be used during the lead up to an election or some other sensitive period. It is more frequently used by non-state actors seeking to disrupt services.[19]

Over and under blocking

[edit]Technical censorship techniques are subject to both over- and under-blocking since it is often impossible to always block exactly the targeted content without blocking other permissible material or allowing some access to targeted material and so providing more or less protection than desired.[6] An example is blocking an IP-address of a server that hosts multiple websites, which prevents access to all of the websites rather than just those that contain content deemed offensive.[20]

Use of commercial filtering software

[edit]

Writing in 2009, Ronald Deibert, professor of political science at the University of Toronto and co-founder and one of the principal investigators of the OpenNet Initiative, and, writing in 2011, Evgeny Morzov, a visiting scholar at Stanford University and an op-ed contributor to The New York Times, explain that companies in the United States, Finland, France, Germany, Britain, Canada, and South Africa are in part responsible for the increasing sophistication of online content filtering worldwide. While the off-the-shelf filtering software sold by Internet security companies are primarily marketed to businesses and individuals seeking to protect themselves and their employees and families, they are also used by governments to block what they consider sensitive content.[21][22]

Among the most popular filtering software programs is SmartFilter by Secure Computing in California, which was bought by McAfee in 2008. SmartFilter has been used by Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, Iran, and Oman, as well as the United States and the UK.[23] Myanmar and Yemen have used filtering software from Websense. The Canadian-made commercial filter Netsweeper[24] is used in Qatar, the UAE, and Yemen.[25] The Canadian organization CitizenLab has reported that Sandvine and Procera products are used in Turkey and Egypt.[26]

On 12 March 2013, in a Special Report on Internet Surveillance, Reporters Without Borders named five "Corporate Enemies of the Internet": Amesys (France), Blue Coat Systems (U.S.), Gamma (UK and Germany), HackingTeam (Italy), and Trovicor (Germany). The companies sell products that are liable to be used by governments to violate human rights and freedom of information. RWB said that the list is not exhaustive and will be expanded in the coming months.[27]

In a U.S. lawsuit filed in May 2011, Cisco is accused of helping the Chinese government build a firewall, known widely as the Golden Shield, to censor the Internet and keep tabs on dissidents.[28] Cisco said it had made nothing special for China. Cisco is also accused of aiding the Chinese government in monitoring and apprehending members of the banned Falun Gong group.[29]

Many filtering programs allow blocking to be configured based on dozens of categories and sub-categories such as these from Websense: "abortion" (pro-life, pro-choice), "adult material" (adult content, lingerie and swimsuit, nudity, sex, sex education), "advocacy groups" (sites that promote change or reform in public policy, public opinion, social practice, economic activities, and relationships), "drugs" (abused drugs, marijuana, prescribed medications, supplements and unregulated compounds), "religion" (non-traditional religions occult and folklore, traditional religions), ....[25] The blocking categories used by the filtering programs may contain errors leading to the unintended blocking of websites.[21] The blocking of Dailymotion in early 2007 by Tunisian authorities was, according to the OpenNet Initiative, due to Secure Computing wrongly categorizing Dailymotion as pornography for its SmartFilter filtering software. It was initially thought that Tunisia had blocked Dailymotion due to satirical videos about human rights violations in Tunisia, but after Secure Computing corrected the mistake access to Dailymotion was gradually restored in Tunisia.[30]

Organizations such as the Global Network Initiative, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Amnesty International, and the American Civil Liberties Union have successfully lobbied some vendors such as Websense to make changes to their software, to refrain from doing business with repressive governments, and to educate schools who have inadvertently reconfigured their filtering software too strictly.[31][32][33] Nevertheless, regulations and accountability related to the use of commercial filters and services are often non-existent, and there is relatively little oversight from civil society or other independent groups. Vendors often consider information about what sites and content is blocked valuable intellectual property that is not made available outside the company, sometimes not even to the organizations purchasing the filters. Thus by relying upon out-of-the-box filtering systems, the detailed task of deciding what is or is not acceptable speech may be outsourced to the commercial vendors.[25]

Non-technical censorship

[edit]

Internet content is also subject to censorship methods similar to those used with more traditional media. For example:[6]

- Laws and regulations may prohibit various types of content and/or require that content be removed or blocked either proactively or in response to requests.

- Publishers, authors, and ISPs may receive formal and informal requests to remove, alter, slant, or block access to specific sites or content.

- Publishers and authors may accept bribes to include, withdraw, or slant the information they present.

- Publishers, authors, and ISPs may be subject to arrest, criminal prosecution, fines, and imprisonment.

- Publishers, authors, and ISPs may be subject to civil lawsuits.

- Equipment may be confiscated and/or destroyed.

- Publishers and ISPs may be closed or required licenses may be withheld or revoked.

- Publishers, authors, and ISPs may be subject to boycotts.

- Publishers, authors, and their families may be subject to threats, attacks, beatings, and even murder.[34]

- Publishers, authors, and their families may be threatened with or actually lose their jobs.

- Individuals may be paid to write articles and comments in support of particular positions or attacking opposition positions, usually without acknowledging the payments to readers and viewers.[35][36]

- Censors may create their own online publications and Web sites to guide online opinion.[35]

- Access to the Internet may be limited due to restrictive licensing policies or high costs.

- Access to the Internet may be limited due to a lack of the necessary infrastructure, deliberate or not.

- Access to search results may be restricted due to government involvement in the censorship of specific search terms, content may be excluded due to terms set with search engines. By allowing search engines to operate in new territory they must agree to abide to censorship standards set by the government in that country.[37]

Censorship of users by web service operators

[edit]Removal of user accounts based on controversial content

[edit]Deplatforming is a form of Internet censorship in which controversial speakers or speech are suspended, banned, or otherwise shut down by social media platforms and other service providers that generally provide a venue for free speech or expression.[38] Banking and financial service providers, among other companies, have also denied services to controversial activists or organizations, a practice known as "financial deplatforming".

Law professor Glenn Reynolds dubbed 2018 the "Year of Deplatforming", in an August 2018 article in The Wall Street Journal.[38] According to Reynolds, in 2018 "the internet giants decided to slam the gates on a number of people and ideas they don't like."[38] On 6 August 2018, for example, several major platforms, including YouTube and Facebook, executed a coordinated, permanent ban on all accounts and media associated with conservative talk show host Alex Jones and his media platform InfoWars, citing "hate speech" and "glorifying violence."[39]

Official statements regarding site and content removal

[edit]Most major web service operators reserve to themselves broad rights to remove or pre-screen content, and to suspend or terminate user accounts, sometimes without giving a specific list or only a vague general list of the reasons allowing the removal. The phrases "at our sole discretion", "without prior notice", and "for other reasons" are common in Terms of service agreements.

- Facebook: Among other things, the Facebook Statement of Rights and Responsibilities says: "You will not post content that: is hateful, threatening, or pornographic; incites violence; or contains nudity or graphic or gratuitous violence", "You will not use Facebook to do anything unlawful, misleading, malicious, or discriminatory", "We can remove any content or information you post on Facebook if we believe that it violates this Statement", and "If you are located in a country embargoed by the United States, or are on the U.S. Treasury Department's list of Specially Designated Nationals you will not engage in commercial activities on Facebook (such as advertising or payments) or operate a Platform application or website".[40]

- Google: Google's general Terms of Service, which were updated on 1 March 2012, state: "We may suspend or stop providing our Services to you if you do not comply with our terms or policies or if we are investigating suspected misconduct", "We may review content to determine whether it is illegal or violates our policies, and we may remove or refuse to display content that we reasonably believe violates our policies or the law", and "We respond to notices of alleged copyright infringement and terminate accounts of repeat infringers according to the process set out in the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act".[41]

- Google Search: Google's Webmaster Tools help includes the following statement: "Google may temporarily or permanently remove sites from its index and search results if it believes it is obligated to do so by law, if the sites do not meet Google's quality guidelines, or for other reasons, such as if the sites detract from users' ability to locate relevant information."[42]

- Twitter: The Twitter Terms of Service state: "We reserve the right at all times (but will not have an obligation) to remove or refuse to distribute any Content on the Services and to terminate users or reclaim usernames" and "We reserve the right to remove Content alleged to be copyright infringing without prior notice and at our sole discretion".[43]

- YouTube: The YouTube Terms of Service include the statements: "YouTube reserves the right to decide whether Content violates these Terms of Service for reasons other than copyright infringement, such as, but not limited to, pornography, obscenity, or excessive length. YouTube may at any time, without prior notice and in its sole discretion, remove such Content and/or terminate a user's account for submitting such material in violation of these Terms of Service", "YouTube will remove all Content if properly notified that such Content infringes on another's intellectual property rights", and "YouTube reserves the right to remove Content without prior notice".[44]

- Wikipedia: The site's content may be modified or deleted by any editor as part of the normal process of editing and updating articles. Wikipedia's deletion policy outlines the circumstances in which entire articles can be deleted. Any editor who believes a page doesn't belong in the encyclopedia can propose its deletion. Such a page can be deleted by any administrator if, after seven days, no one objects to the proposed deletion. Speedy deletion allows for outright deletion of articles that are so clearly in violation of rules of the website that they do not need to undergo a full deletion discussion. All deletion decisions may be reviewed, either informally or formally. An additional means of hiding specific content within Wikipedia articles is revision deletion, or RevDel, by which an administrator can perform sanitization/redaction of specific revisions of an article, thereby hiding certain information from the view of non-administrators.[45][46]: 216

- Yahoo: Yahoo!'s Terms of Service (TOS) state: "You acknowledge that Yahoo! may or may not pre-screen Content, but that Yahoo! and its designees shall have the right (but not the obligation) in their sole discretion to pre-screen, refuse, or remove any Content that is available via the Yahoo! Services. Without limiting the foregoing, Yahoo! and its designees shall have the right to remove any Content that violates the TOS or is otherwise objectionable."[47]

Circumvention

[edit]Internet censorship circumvention is one of the processes used by technologically savvy Internet users to bypass the technical aspects of Internet filtering and gain access to the otherwise censored material. Circumvention is an inherent problem for those wishing to censor the Internet because filtering and blocking do not remove content from the Internet, but instead block access to it. Therefore, as long as there is at least one publicly accessible uncensored system, it will often be possible to gain access to the otherwise censored material. However circumvention may not be possible by non-tech-savvy users, so blocking and filtering remain effective means of censoring the Internet access of large numbers of users.[6]

Different techniques and resources are used to bypass Internet censorship, including proxy websites, virtual private networks, sneakernets, the dark web and circumvention software tools. Solutions have differing ease of use, speed, security, and risks. Most, however, rely on gaining access to an Internet connection that is not subject to filtering, often in a different jurisdiction not subject to the same censorship laws. According to GlobalWebIndex, over 400 million people use virtual private networks to circumvent censorship or for an increased level of privacy.[5] The majority of circumvention techniques are not suitable for day to day use.[48]

There are risks to using circumvention software or other methods to bypass Internet censorship. In some countries, individuals that gain access to otherwise restricted content may be violating the law and if caught can be expelled, fired, jailed, or subject to other punishments and loss of access.[3][49]

In June 2011, The New York Times reported that the U.S. is engaged in a "global effort to deploy 'shadow' Internet and mobile phone systems that dissidents can use to undermine repressive governments that seek to silence them by censoring or shutting down telecommunications networks."[50]

Another way to circumvent Internet censorship is to physically go to an area where the Internet is not censored. In 2017, a so-called "Internet refugee camp" was established by IT workers in the village of Bonako, just outside an area of Cameroon where the Internet is regularly blocked.[51][52]

Increased use of HTTPS

[edit]The use of HTTPS versus what originally was HTTP in web searches created greater accessibility to most sites originally blocked or heavily monitored. Many social media sites including, Facebook, Google, and Twitter have added an automatic redirection to HTTPS as of 2017.[53] With the added adoption of HTTPS use, "censors" are left with limited options of either completely blocking all content or none of it.[54]

The use of HTTPS does not inherently prevent the censorship of an entire domain, as the domain name is left unencrypted in the ClientHello of the TLS handshake. The Encrypted Client Hello TLS extension expands on HTTPS and encrypts the entire ClientHello but this depends on both client and server support.[55][56]

Common targets

[edit]There are several motives or rationales for Internet filtering: politics and power, social norms and morals, and security concerns. Protecting existing economic interests is an additional emergent motive for Internet filtering. In addition, networking tools and applications that allow the sharing of information related to these motives are themselves subjected to filtering and blocking. And while there is considerable variation from country to country, the blocking of web sites in a local language is roughly twice that of web sites available only in English or other international languages.[11]

Politics and power

[edit]Censorship directed at political opposition to the ruling government is common in authoritarian and repressive regimes. Some countries block web sites related to religion and minority groups, often when these movements represent a threat to the ruling regimes.[11]

Examples include:

- Political blogs and websites[57]

- Lèse-majesté sites, sites with content that offends the dignity of or challenges the authority of a reigning sovereign or of a state

- Falun Gong and Tibetan exile group sites in China or Buddhist, Cao Dai faith, and indigenous hill tribes sites in Vietnam

- 50 Cent Party, or "50 Cent Army" that worked to sway negative public opinion on the Chinese Communist Party[58]

- Russian web brigades

- Sites aimed at religious conversion from Islam to Christianity[11]

- Sites criticizing the government or an authority in the country[59]

- Sites that comment on political parties that oppose the current government of a country[59]

- Sites that accuse authorities of corruption[59]

- Sites that comment on minorities or LGBTQ issues[59]

- Communist symbols and imagery in Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, Georgia, Latvia, Moldova, Hungary, and Indonesia

- Neo-Nazi and similar websites, particularly in France and Germany[60]

Social norms

[edit]Social filtering is censorship of topics that are held to be antithetical to accepted societal norms.[11] In particular censorship of child pornography and content deemed inappropriate for children enjoys very widespread public support and such content is subject to censorship and other restrictions in most countries.

Examples include:

- Sites that include hate speech inciting racism, sexism, homophobia, or other forms of bigotry

- Sites seen as promoting illegal drug use (such as Erowid)[61]

- Sex and erotic, fetishism, prostitution, and pornographic sites

- Child pornography and pedophile-related sites (see also CIRCAMP)

- Gambling sites

- Sites encouraging or inciting violence[59]

- Sites promoting criminal activity[59]

- Sites that contain blasphemous content, particularly when directed at a majority or state supported religion[59]

- Sites that contain defamatory, slanderous, or libelous content[59]

- Sites that include political satire[59]

- Sites that contain information on social issues or "online protests, petitions and campaigns"[59]

Security concerns

[edit]Many organizations implement filtering as part of a defense in depth strategy to protect their environments from malware,[62] and to protect their reputations in the event of their networks being used, for example, to carry out sexual harassment.

Internet filtering related to threats to national security that targets the Web sites of insurgents, extremists, and terrorists often enjoys wide public support.[11]

Examples include:

- Blocking of pro–North Korean sites by South Korea[63]

- Blocking of sites of groups that foment domestic conflict in India[11]

- Blocking of sites of the Muslim Brotherhood in some countries in the Middle East

- Blocking of sites such as 4chan thought to be related to the internet hacker group Anonymous[64]

Protection of existing economic interests and copyright

[edit]The protection of existing economic interests is sometimes the motivation for blocking new Internet services such as low-cost telephone services that use Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP). These services can reduce the customer base of telecommunications companies, many of which enjoy entrenched monopoly positions and some of which are government sponsored or controlled.[11]

Anti-copyright activists Christian Engström, Rick Falkvinge and Oscar Swartz have alleged that censorship of child pornography is being used as a pretext by copyright lobby organizations to get politicians to implement similar site blocking legislation against copyright-related piracy.[65]

Examples include:

- File sharing and peer-to-peer (P2P) related websites such as The Pirate Bay

- Skype

- Sites that sell or distribute music, but are not 'approved' by rights holders, such as AllOfMP3

Network tools

[edit]Blocking the intermediate tools and applications of the Internet that can be used to assist users in accessing and sharing sensitive material is common in many countries.[11]

Examples include:

- Media sharing websites (e.g. Flickr and YouTube)[66]

- Social networks (e.g. Facebook and Instagram)

- Translation sites and tools

- E-mail providers

- Web hosting sites

- Blog hosting sites such as Blogspot and Medium

- Microblogging sites such as Twitter and Weibo[67]

- Wikipedia

- Censorship circumvention sites

- Search engines such as Bing[68] and Google[69][70] – particularly in Mainland China and Cuba[71]

Information about individuals

[edit]The right to be forgotten is a concept that has been discussed and put into practice in the European Union. In May 2014, the European Court of Justice ruled against Google in Costeja, a case brought by a Spanish man who requested the removal of a link to a digitized 1998 article in La Vanguardia newspaper about an auction for his foreclosed home, for a debt that he had subsequently paid.[72] He initially attempted to have the article removed by complaining to Spain's data protection agency—Agencia Española de Protección de Datos—which rejected the claim on the grounds that it was lawful and accurate, but accepted a complaint against Google and asked Google to remove the results.[73] Google sued in Spain and the lawsuit was transferred to the European Court of Justice. The court ruled in Costeja that search engines are responsible for the content they point to and thus, Google was required to comply with EU data privacy laws.[74][75] It began compliance on 30 May 2014 during which it received 12,000 requests to have personal details removed from its search engine.[76]

Index on Censorship claimed that "Costeja ruling ... allows individuals to complain to search engines about information they do not like with no legal oversight. This is akin to marching into a library and forcing it to pulp books. Although the ruling is intended for private individuals it opens the door to anyone who wants to whitewash their personal history....The Court's decision is a retrograde move that misunderstands the role and responsibility of search engines and the wider internet. It should send chills down the spine of everyone in the European Union who believes in the crucial importance of free expression and freedom of information."[77]

Resilience

[edit]Various contexts influence whether or not an internet user will be resilient to censorship attempts. Users are more resilient to censorship if they are aware that information is being manipulated. This awareness of censorship leads to users finding ways to circumvent it. Awareness of censorship also allows users to factor this manipulation into their belief systems. Knowledge of censorship also offers some citizens incentive to try to discover information that is being concealed. In contrast, those that lack awareness of censorship cannot easily compensate for information manipulation.[78]

Other important factors for censorship resiliency are the demand for the information being concealed, and the ability to pay the costs to circumvent censorship. Entertainment content is more resilient to online censorship than political content, and users with more education, technology access, and wider, more diverse social networks are more resilient to censorship attempts.[78]

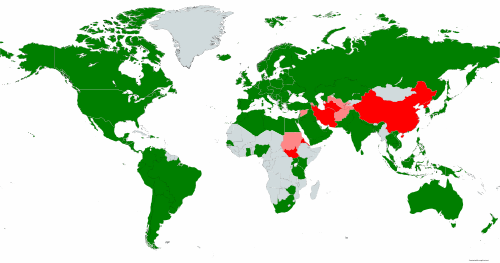

Around the world

[edit]As more people in more places begin using the Internet for important activities, there is an increase in online censorship, using increasingly sophisticated techniques. The motives, scope, and effectiveness of Internet censorship vary widely from country to country. The countries engaged in state-mandated filtering are clustered in three main regions of the world: east Asia, central Asia, and the Middle East/North Africa.

Countries in other regions also practice certain forms of filtering. In the United States, state-mandated Internet filtering occurs on some computers in libraries and K–12 schools. Content related to Nazism or Holocaust denial is blocked in France and Germany. Child pornography and hate speech are blocked in many countries throughout the world.[79] In fact, many countries throughout the world, including some democracies with long traditions of strong support for freedom of expression and freedom of the press, are engaged in some amount of online censorship, often with substantial public support.[80]

Internet censorship in China is among the most stringent in the world. The government blocks Web sites that discuss the Dalai Lama, the 1989 crackdown on Tiananmen Square protesters, the banned spiritual practice Falun Gong, as well as many general Internet sites.[81] The government requires Internet search firms and state media to censor issues deemed officially "sensitive," and blocks access to foreign websites including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.[82] According to a study in 2014,[83] censorship in China is used to muzzle those outside government who attempt to spur the creation of crowds for any reason—in opposition to, in support of, or unrelated to the government.

There are international bodies that oppose internet censorship, for example "Internet censorship is open to challenge at the World Trade Organization (WTO) as it can restrict trade in online services, a forthcoming study argues".[84]

International concerns

[edit]Generally, national laws affecting content within a country only apply to services that operate within that country and do not affect international services, but this has not been established clearly by international case law. There are concerns that due to the vast differences in freedom of speech between countries, that the ability for one country to affect speech across the global Internet could have chilling effects.

For example, Google had won a case at the European Court of Justice in September 2019 that ruled that the EU's right to be forgotten only applied to services within the EU, and not globally.[85] But in a contrary decision in October 2019, the same court ruled that Facebook was required to globally comply with a takedown request made in relationship to defamatory material that was posted to Facebook by an Austrian that was libelous of another, which had been determined to be illegal under Austrian laws. The case created a problematic precedent that the Internet may become subject to regulation under the strictest national defamation laws, and would limit free speech that may be acceptable in other countries.[86]

Internet shutdowns

[edit]Several governments have resorted to shutting down most or all Internet connections in all or part of the country.

This appears to have been the case on 27 and 28 January 2011 during the 2011 Egyptian revolution, in what has been widely described as an "unprecedented" internet block.[87][88] About 3500 Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) routes to Egyptian networks were shut down from about 22:10 to 22:35 UTC 27 January.[87] This full block was implemented without cutting off major intercontinental fibre-optic links, with Renesys stating on 27 January, "Critical European-Asian fiber-optic routes through Egypt appear to be unaffected for now."[87] Full blocks also occurred in Myanmar/Burma in 2007,[89] Libya in 2011,[90] Iran in 2019,[91] and Syria during the Syrian civil war.

Almost all Internet connections in Sudan were disconnected from 3 June to 9 July 2019, in response to a political opposition sit-in seeking civilian rule.[92][93] A near-complete shutdown in Ethiopia lasted for a week after the Amhara Region coup attempt.[94] A week-long shutdown in Mauritania followed disputes over the 2019 Mauritanian presidential election.[95] Other country-wide shutdowns in 2019 include Zimbabwe after a gasoline price protests triggered police violence, Gabon during the 2019 Gabonese coup attempt, and during or after elections in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Benin, Malawi, and Kazakhstan.[96]

Local shutdowns are frequently ordered in India during times of unrest and security concerns.[97][98] Some countries have used localized Internet shutdowns to combat cheating during exams, including Iraq,[99] Ethiopia, India, Algeria, and Uzbekistan.[96]

The Iranian government imposed a total internet shutdown from 16 to 23 November 2019, in response to the fuel protests.[100] Doug Madory, the director of Internet analysis at Oracle, has described the operation as "unusual in its scale" and way more advanced.[101] Beginning Saturday afternoon on 16 November 2019, the government of Iran ordered the disconnection of much of the country's internet connectivity as a response to widespread protests against the government's decision to raise gas prices. While Iran is no stranger to government-directed interference in its citizens’ access to the internet, this outage is notable in how it differs from past events. Unlike previous efforts at censorship and bandwidth throttling, the internet of Iran is presently experiencing a multi-day wholesale disconnection for much of its population – arguably the largest such event ever for Iran.[101][102][103]

Reports, ratings, and trends

[edit]

Detailed country by country information on Internet censorship is provided by the OpenNet Initiative, Reporters Without Borders, Freedom House, V-Dem Institute, Access Now and in the US State Department Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor's Human Rights Reports.[104] The ratings produced by several of these organizations are summarized in the Internet censorship and surveillance by country and the Censorship by country articles.

OpenNet Initiative reports

[edit]Through 2010, the OpenNet Initiative had documented Internet filtering by governments in over forty countries worldwide.[25] The level of filtering in 26 countries in 2007 and in 25 countries in 2009 was classified in the political, social, and security areas. Of the 41 separate countries classified, seven were found to show no evidence of filtering in all three areas (Egypt, France, Germany, India, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and United States), while one was found to engage in pervasive filtering in all three areas (China), 13 were found to engage in pervasive filtering in one or more areas, and 34 were found to engage in some level of filtering in one or more areas. Of the 10 countries classified in both 2007 and 2009, one reduced its level of filtering (Pakistan), five increased their level of filtering (Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, South Korea, and Uzbekistan), and four maintained the same level of filtering (China, Iran, Myanmar, and Tajikistan).[6][105]

Freedom on the Net reports

[edit]The Freedom on the Net reports from Freedom House provide analytical reports and numerical ratings regarding the state of Internet freedom for countries worldwide.[106] The countries surveyed represent a sample with a broad range of geographical diversity and levels of economic development, as well as varying levels of political and media freedom. The surveys ask a set of questions designed to measure each country's level of Internet and digital media freedom, as well as the access and openness of other digital means of transmitting information, particularly mobile phones and text messaging services. Results are presented for three areas: Obstacles to Access, Limits on Content, and Violations of User Rights. The results from the three areas are combined into a total score for a country (from 0 for best to 100 for worst) and countries are rated as "Free" (0 to 30), "Partly Free" (31 to 60), or "Not Free" (61 to 100) based on the totals.

Starting in 2009 Freedom House has produced nine editions of the report.[107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][106] There was no report in 2010. The reports generally cover the period from June through May.

Freedom on the Net Survey Results 2009[107] 2011[108] 2012[109] 2013[110] 2014[111] 2015[112] 2016[113] 2017[114] 2018[106] Countries 15 37 47 60 65 65 65 65 65 Free 4 (27%) 8 (22%) 14 (30%) 17 (29%) 19 (29%) 18 (28%) 17 (26%) 16 (25%) 15 (23%) Partly free 7 (47%) 18 (49%) 20 (43%) 29 (48%) 31 (48%) 28 (43%) 28 (43%) 28 (43%) 30 (46%) Not free 4 (27%) 11 (30%) 13 (28%) 14 (23%) 15 (23%) 19 (29%) 20 (31%) 21 (32%) 20 (31%) Improved n/a 5 (33%) 11 (31%) 12 (26%) 12 (18%) 15 (23%) 34 (52%) 32 (49%) 19 (29%) Declined n/a 9 (60%) 17 (47%) 28 (60%) 36 (55%) 32 (49%) 14 (22%) 13 (20%) 26 (40%) No change n/a 1 (7%) 8 (22%) 7 (15%) 17 (26%) 18 (28%) 17 (26%) 20 (31%) 20 (31%)

The 2014 report assessed 65 countries and reported that 36 countries experienced a negative trajectory in Internet freedom since the previous year, with the most significant declines in Russia, Turkey and Ukraine. According to the report, few countries demonstrated any gains in Internet freedom, and the improvements that were recorded reflected less vigorous application of existing controls rather than new steps taken by governments to actively increase Internet freedom. The year's largest improvement was recorded in India, where restrictions to content and access were relaxed from what had been imposed in 2013 to stifle rioting in the northeastern states. Notable improvement was also recorded in Brazil, where lawmakers approved the bill Marco Civil da Internet, which contains significant provisions governing net neutrality and safeguarding privacy protection.[111]

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

[edit]RWB "Internet enemies" and "countries under surveillance" lists

[edit]In 2006, Reporters without Borders (Reporters sans frontières, RSF), a Paris-based international non-governmental organization that advocates freedom of the press, started publishing a list of "Enemies of the Internet".[115] The organization classifies a country as an enemy of the internet because "all of these countries mark themselves out not just for their capacity to censor news and information online but also for their almost systematic repression of Internet users."[116] In 2007 a second list of countries "Under Surveillance" (originally "Under Watch") was added.[117]

Enemies of the Internet:[118][119]

|

Current Countries Under Surveillance:[118][failed verification]

Past Countries Under Surveillance:

|

When the "Enemies of the Internet" list was introduced in 2006, it listed 13 countries. From 2006 to 2012 the number of countries listed fell to 10 and then rose to 12. The list was not updated in 2013. In 2014 the list grew to 19 with an increased emphasis on surveillance in addition to censorship. The list has not been updated since 2014.

When the "Countries under surveillance" list was introduced in 2008, it listed 10 countries. Between 2008 and 2012 the number of countries listed grew to 16 and then fell to 11. The number grew to 12 with the addition of Norway in 2020. The list was last updated in 2020.[citation needed]

RWB Special report on Internet Surveillance

[edit]On 12 March 2013, Reporters Without Borders published a Special report on Internet Surveillance.[27] The report includes two new lists:

- a list of "State Enemies of the Internet", countries whose governments are involved in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights; and

- a list of "Corporate Enemies of the Internet", companies that sell products that are liable to be used by governments to violate human rights and freedom of information.

The five "State Enemies of the Internet" named in March 2013 are: Bahrain, China, Iran, Syria, and Vietnam.[27]

The five "Corporate Enemies of the Internet" named in March 2013 are: Amesys (France), Blue Coat Systems (U.S.), Gamma Group (UK and Germany), HackingTeam (Italy), and Trovicor (Germany).[27]

V-Dem Digital Societies Project

[edit]The V-Dem Digital Societies Project measures a range of questions related to internet censorship, misinformation online, and internet shutdowns.[120] This annual report includes 35 indicators assessing five areas: disinformation, digital media freedom, state regulation of digital media, polarization of online media, and online social cleavages.[121] The data set uses V-Dem's methodology of aggregating surveys of experts from around the world.[121] It has been updated each year starting in 2019, with data covering from 2000–2021.[121] These ratings are more similar to other expert analyses like Freedom House than remotely sensed data from Access Now.[122]

Access Now #KeepItOn

[edit]Access Now maintains an annual list of internet shutdowns, throttling, and blockages as part of the #KeepItOn project.[122][123][124] These data track several features of shutdowns including their location, their duration, the particular services impacted, the government's justification for the shutdown, and actual reasons for the shutdown as reported by independent media.[125] Unlike Freedom House or V-Dem, Access Now detects shutdowns using remote sensing and then confirms these instances with reports from civil society, government, in-country volunteers, or ISPs.[125][122] These methods have been found to be less prone to false positives.[122]

BBC World Service global public opinion poll

[edit]A poll of 27,973 adults in 26 countries, including 14,306 Internet users,[126] was conducted for the BBC World Service by the international polling firm GlobeScan using telephone and in-person interviews between 30 November 2009 and 7 February 2010. GlobeScan Chairman Doug Miller felt, overall, that the poll showed that:

- Despite worries about privacy and fraud, people around the world see access to the internet as their fundamental right. They think the web is a force for good, and most don't want governments to regulate it.[127]

Findings from the poll include:[127]

- Nearly four in five (78%) Internet users felt that the Internet had brought them greater freedom.

- Most Internet users (53%) felt that "the internet should never be regulated by any level of government anywhere".

- Opinion was evenly split between Internet users who felt that "the internet is a safe place to express my opinions" (48%) and those who disagreed (49%). Users in Germany and France agreed the least, followed by users in a highly filtered country such as China, while users in Egypt, India and Kenya agreed more strongly.[6]

- The aspects of the Internet that cause the most concern include: fraud (32%), violent and explicit content (27%), threats to privacy (20%), state censorship of content (6%), and the extent of corporate presence (3%).

- Almost four in five Internet users and non-users around the world felt that access to the Internet was a fundamental right (50% strongly agreed, 29% somewhat agreed, 9% somewhat disagreed, 6% strongly disagreed, and 6% gave no opinion).[128] And while there is strong support for this right in all of the countries surveyed, it is surprising that the United States and Canada were among the top five countries where people most strongly disagreed that access to the Internet was a fundamental right of all people (13% in Japan, 11% in the U.S., 11% in Kenya, 11% in Pakistan, and 10% in Canada strongly disagree).[6]

Internet Society's Global Internet User Survey

[edit]In July and August 2012, the Internet Society conducted online interviews of more than 10,000 Internet users in 20 countries. Some of the results relevant to Internet censorship are summarized below.[129]

| Question | No. of Responses | Responses[130] |

|---|---|---|

| Access to the Internet should be considered a basic human right. | 10,789 | 83% somewhat or strongly agree, 14% somewhat or strongly disagree, 3% don't know |

| Freedom of expression should be guaranteed on the Internet. | 10,789 | 86% somewhat or strongly agree, 11% somewhat or strongly disagree, 2% don't know |

| The Internet should be governed in some form to protect the community from harm. | 10,789 | 82% somewhat or strongly agree, 15% somewhat or strongly disagree, 3% don't know / not applicable |

| Censorship should exist in some form on the Internet. | 10,789 | 71% somewhat or strongly agree, 24% somewhat or strongly disagree, 5% don't know / not applicable |

| Each individual country has the right to govern the Internet the way they see fit. | 10,789 | 67% somewhat or strongly agree, 29% somewhat or strongly disagree, 4% don't know / not applicable |

| The Internet does more to help society than it does to hurt it. | 10,789 | 83% somewhat or strongly agree, 13% somewhat or strongly disagree, 4% don't know / not applicable |

| How often do you read the privacy policies of websites or services that you share personal information with? | 10,789 | 16% all the time, 31% most of the time, 41% sometimes, 12% never |

| When you are logged in to a service or application do you use privacy protections? | 10,789 | 27% all the time, 36% most of the time, 29% sometimes, 9% never |

| Do you use "anonymization" services, for example, the "anonymize" feature in your web browser, specialized software like Tor, third - party redirection services like duckduckgo.com? | 10,789 | 16% yes, 38% no, 43% don't know / not aware of these types of services, 3% would like to use them but I am not able to |

| Increased government control of the Internet would put limits on the content I can access. | 9,717 | 77% somewhat or strongly agree, 18% somewhat or strongly disagree, 4% don't know / not applicable |

| Increased government control of the Internet would limit my freedom of expression. | 9,717 | 74% somewhat or strongly agree, 23% somewhat or strongly disagree, 4% don't know / not applicable |

| Increased government control of the Internet would improve the content on the Internet. | 9,717 | 49% somewhat or strongly agree, 44% somewhat or strongly disagree, 7% don't know / not applicable |

| Increased government control of the Internet would make the Internet safe for everyone to use. | 9,717 | 58% somewhat or strongly agree, 35% somewhat or strongly disagree, 7% don't know / not applicable |

| Increased government control of the Internet would have no effect. | 9,717 | 31% somewhat or strongly agree, 56% somewhat or strongly disagree, 14% don't know / not applicable |

| To what degree would you accept increased control or monitoring of the Internet if you gained increased safety? | 10,789 | 61% a lot or somewhat, 23% not very much or not at all |

Transparency of filtering or blocking activities

[edit]Among the countries that filter or block online content, few openly admit to or fully disclose their filtering and blocking activities. States are frequently opaque and/or deceptive about the blocking of access to political information.[10] For example:

- Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are among the few states that publish detailed information about their filtering practices and display a notification to the user when attempting to access a blocked website. The websites that are blocked are mostly pornographic or considered un-Islamic.

- In contrast, countries such as China and Tunisia send users a false error indication. China blocks requests by users for a banned website at the router level and a connection error is returned, effectively preventing the user's IP address from making further HTTP requests for a varying time, which appears to the user as "time-out" error with no explanation. Tunisia has altered the block page functionality of SmartFilter, the commercial filtering software it uses, so that users attempting to access blocked websites receive a fake "File not found" error page.

- In Uzbekistan, users are frequently sent block pages stating that the website is blocked because of pornography, even when the page contains no pornography. Uzbeki ISPs may also redirect users' request for blocked websites to unrelated websites, or sites similar to the banned websites, but with different information.[131]

Arab Spring

[edit]During the Arab Spring of 2011, media jihad (media struggle) was extensive. Internet and mobile technologies, particularly social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, played and are playing important new and unique roles in organizing and spreading the protests and making them visible to the rest of the world. An activist in Egypt tweeted, "we use Facebook to schedule the protests, Twitter to coordinate, and YouTube to tell the world".[132]

This successful use of digital media in turn led to increased censorship including the complete loss of Internet access for periods of time in Egypt[87][88][133] and Libya in 2011.[90][134] In Syria, the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA), an organization that operates with at least tacit support of the government, claims responsibility for defacing or otherwise compromising scores of websites that it contends spread news hostile to the Syrian government. SEA disseminates denial of service (DoS) software designed to target media websites including those of Al Jazeera, BBC News, Syrian satellite broadcaster Orient TV, and Dubai-based Al Arabiya TV.[135]

In response to the greater freedom of expression brought about by the Arab Spring revolutions in countries that were previously subject to very strict censorship, in March 2011, Reporters Without Borders moved Tunisia and Egypt from its "Internet enemies" list to its list of countries "under surveillance"[136] and in 2012 dropped Libya from the list entirely.[118] At the same time, there were warnings that Internet censorship might increase in other countries following the events of the Arab Spring.[137][138] However, in 2013, Libyan communication company LTT blocked the pornographic websites.[139] It even blocked the family-filtered videos of ordinary websites like Dailymotion.[140]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]During the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia was reported to have blocked the internet websites Twitter and Facebook. Facebook was noted as being suspended due to an objection to its policy of reviewing news stories for authenticity where they were produced by Russian state-backed media before allowing them to be published on its platform. It was subject to a total ban whereas Twitter was suspended regionally. Reports have identified that VPN use has enabled people to circumvent the restrictions by installing software.[141]

It been reported that the European Union would seek to censor Russian media outlets regarded as producing propaganda.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]|

Organizations and projects

|

Topics

|

References

[edit]- ^ "What is Internet Censorship?". www.iplocation.net. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ The Editorial Board (15 October 2018). "There May Soon Be Three Internets. America's Won't Necessarily Be the Best. - A breakup of the web grants privacy, security and freedom to some, and not so much to others". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Schmidt, Eric E.; Cohen, Jared (11 March 2014). "The Future of Internet Freedom". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Goldberg, Erica (2016). "Free Speech Consequentialism". Columbia Law Review. 116 (3): 687–694. JSTOR 43783393.

- ^ a b Marcello Mari. How Facebook's Tor service could encourage a more open web Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Friday 5 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Freedom of connection, freedom of expression: the changing legal and regulatory ecology shaping the Internet Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Dutton, March 2003

- ^ "First Nation in Cyberspace", Philip Elmer-Dewitt, Time, 6 December 1993, No.49

- ^ "Cerf sees government control of Internet failing" Archived 3 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Pedro Fonseca, Reuters, 15 November 2006

- ^ 2007 Circumvention Landscape Report: Methods, Uses, and Tools Archived 11 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Hal Roberts, Ethan Zuckerman, and John Palfrey, Beckman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, March 2009

- ^ a b Chadwick, Andrew (2009). Routledge handbook of Internet politics. Routledge international handbooks. Taylor and Francis. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-415-42914-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Measuring Global Internet Filtering" Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Faris and Nart Villeneuve, in Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Ronald Deibert, John Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski, and Jonathan Zittrain, eds., MIT Press (Cambridge), 2008

- ^ Lao Wai (21 October 2007). "I've Been Rivercrabbed!". An American in Beijing. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ a b Jones, Ben; Feamster, Nick; Hall, Joseph; Adams, Stan; Aaron, Michael (23 August 2019). "A Survey of Worldwide Censorship Techniques". IETF. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Hoffman, Chris (22 September 2016). "How the "Great Firewall of China" Works to Censor China's Internet". www.howtogeek.com. How to geek. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ For an example, see Wikipedia:Advice to users using Tor to bypass the Great Firewall

- ^ Tom Espiner (4 July 2006). "Academics break the Great Firewall of China". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy. "The Ingenious Way Iranians Are Using Satellite TV to Beam in Banned Internet". WIRED. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Google excluding controversial sites Archived 23 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Declan McCullagh, CNET News, 23 October 2002, 8:55 pm PDT. Retrieved 22 April 2007 00:40 UTC

- ^ "The Emergence of Open and Organized Pro-Government Cyber Attacks in the Middle East: The Case of the Syrian Electronic Army" Archived 14 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Helmi Noman, OpenNet Initiative, May 2011

- ^ "India blocks Yahoo! Groups" Archived 17 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Andrew Orlowski, The Register, 24 September 2003

- ^ a b Chadwick, Andrew (2009). Routledge handbook of Internet politics. Routledge international handbooks. Taylor and Francis. pp. 330–331. ISBN 978-0-415-42914-6.

- ^ "Political Repression 2.0" Archived 12 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Evgeny Morzov, Op-Ed Contributor to the New York Times, 1 September 2011

- ^ Glanville, Jo (17 November 2008). "The big business of net censorship". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Internet content filtering" Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Netsweeper, Inc. web site. Retrieved 1 September 2011

- ^ a b c d "West Censoring East: The Use of Western Technologies by Middle East Censors, 2010–2011" Archived 18 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Helmi Noman and Jillian C. York, OpenNet Initiative, March 2011

- ^ "BAD TRAFFIC: Sandvine's PacketLogic Devices Used to Deploy Government Spyware in Turkey and Redirect Egyptian Users to Affiliate Ads?". The Citizen Lab. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d The Enemies of the Internet Special Edition : Surveillance Archived 31 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders, 12 March 2013

- ^ "The Great Firewall of China". National Council for the Social Studies. 27 May 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Somini Sengupta (2 September 2011). "Group Says It Has New Evidence of Cisco's Misdeeds in China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020.

- ^ Chadwick, Andrew (2009). Routledge handbook of Internet politics. Routledge international handbooks. Taylor and Francis. pp. 323–324. ISBN 978-0-415-42914-6.

- ^ "R.I. ACLU releases report on "troubling" internet censorship in public libraries" (Press release). ACLU. 18 April 2005. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. The Rhode Island affiliate, American Civil Liberties Union (April 2005). Reader's block: Internet censorship in Rhode Island public libraries (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2005.

- ^ Sutton, Maira; Timm, Trevor (7 November 2011). "This Week in Internet Censorship Egypt Imprisons Alaa, Other Pro-democracy Bloggers". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ China: Controls tighten as Internet activism grows Archived 25 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine "Cisco Systems, Microsoft, Nortel Networks, Websense and Sun Microsystems", citing Amnesty International: People's Republic of China: State Control of the Internet in China, ASA, 17/007/2002, November 2002.

- ^ "In Mexico, Social Media Become a Battleground in the Drug War" Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, J. David Goodman, The Lede, The New York Times, 15 September 2011

- ^ a b Provision of information in this fashion is in keeping with principles of freedom of expression, as long as it is done transparently and does not overwhelm alternative sources of information.

- ^ "China's growing army of paid internet commentators" Archived 13 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Sarah Cook and Maggie Shum, Freedom House, 11 October 2011

- ^ Farrell, Michael B (22 March 2010). "Google Ends Internet Censorship, Dares China to Make Next Move". link.galegroup.com. The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Glenn Harlan (18 August 2018). "When Digital Platforms Become Censors". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019.

- ^ Chappell, Bill; Tsioulcas, Anastasia (6 August 2018). "YouTube, Apple and Facebook Ban Infowars, Which Decries 'Mega Purge'". NPR. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "Statement of Rights and Responsibilities" Archived 26 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Facebook, 26 April 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011

- ^ "Google Terms of Service" Archived 15 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Policies & Principles, Google, Inc.. Retrieved 1 April 2012

- ^ "Why does Google remove sites from the Google index?" Archived 6 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Google Webmaster Tools Help. Retrieved 22 April 2007 00:43 UTC

- ^ "Terms of Service" Archived 15 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Twitter, 1 June 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011

- ^ "Terms of Service" Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, YouTube, 9 June 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2011

- ^ West, Andrew Granville; Lee, Insup (October 2011). "What Wikipedia deletes: Characterizing dangerous collaborative content". Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Wikis and Open Collaboration. pp. 25–28. doi:10.1145/2038558.2038563. ISBN 978-1-4503-0909-7. S2CID 10396423.

- ^ Jemielniak, Dariusz (2014). Common Knowledge?: An Ethnography of Wikipedia. Stanford University Press.

- ^ "Yahoo! Terms of Service" Archived 18 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Yahoo!, 24 November 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2011

- ^ Roberts, H., Zuckerman, E., & Palfrey, J. (2009, March). 2007 Circumvention Landscape Report: Methods, Uses, and Tools (Rep.). Retrieved 18 March 2016, from The Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

- ^ "Risks" Archived 8 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Internet censorship wiki. Retrieved 2 September 2011

- ^ "U.S. Underwrites Internet Detour Around Censors" Archived 11 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, James Glanz and John Markoff, The New York Times, 12 June 2011

- ^ Dahir, Abdi Latif (28 March 2017). "Reeling from an internet shutdown, startups in Cameroon have created an "internet refugee camp"". Quartz Africa. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Ritzen, Yarno (26 January 2018). "Cameroon internet shutdowns cost Anglophones millions". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Connolly, Amanda (27 January 2016). "Medium stands by journalists as Malaysia blocks the site". The Next Web. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Zittrain, Jonathan; Faris, Robert; Noman, Helmi; Clark, Justin; Tilton, Casey; Morrison-Westphal, Ryan (June 2017). "The Shifting Landscape of Global Internet Censorship" (PDF). Dash.Harvard.Edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Encrypting SNI: Fixing One of the Core Internet Bugs". The Cloudflare Blog. 24 September 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Oku, Kazuho; Wood, Christopher; Rescorla, Eric; Sullivan, Nick (June 2020). "Encrypted Server Name Indication for TLS 1.3". IETF. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Blog censorship gains support". CNET. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Far Eastern Economic Review | China's Guerrilla War for the Web". 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Which Countries Censor the Internet?". Time Magazine. 23 November 2015. p. 36. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Latest Stories From News.Com.Au". Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ Russia Bans the Wikipedia of Drugs Archived 11 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine The Fix 2013-02-28

- ^ "Why Malware Filtering Is Necessary in the Web Gateway". Gartner. 26 August 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Collateral Blocking: Filtering by South Korean Government of Pro-North Korean Websites" Archived 9 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, OpenNet Initiative: Bulletin 009, 31 January 2005

- ^ "Federal authorities take on Anonymous hackers" Archived 9 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press in the Washington Post, 12 September 2011

- ^ Rick Falkvinge (9 July 2011). "The Copyright Lobby Absolutely Loves Child Pornography". TorrentFreak. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "YouTube Blocked in...Thailand". Mashable. 11 March 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "China struggles to tame microblogging masses" Archived 4 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Agence France-Presse (AFP) in The Independent, 8 September 2011

- ^ "Sex, Social Mores, and Keyword Filtering: Microsoft Bing in the "Arabian Countries Archived 13 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine", Helmi Noman, OpenNet Initiative, March 2010

- ^ "Google Search & Cache Filtering Behind China's Great Firewall" Archived 8 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, OpenNet Initiative: Bulletin 006, 3 September 2004

- ^ "Empirical Analysis of Google SafeSearch" Archived 4 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Benjamin Edelman, Berkman Center for Internet & Society, Harvard Law School, 13 April 2003

- ^ "China blocking Google". BBC News. 2 September 2002. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Julia Powles (15 May 2014). "What we can salvage from 'right to be forgotten' ruling". Wired.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Solon, Olivia (13 May 2014). "People have the right to be forgotten, rules EU court". Wired.co.uk. Conde Nast Digital. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "EU court backs 'right to be forgotten' in Google case". BBC News. 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "EU court rules Google must tweak search results in test of "right to be forgotten"". CBS News. 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Removal of Google personal information could become work intensive". Europe News.Net. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ "Index blasts EU court ruling on "right to be forgotten"". indexoncensorship.org. 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b Roberts, Margaret E. (2020). "Resilience to Online Censorship". Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 401–419. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-032837.

- ^ "Introduction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2011., Jonathan Zittrain and John Palfrey, in Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Ronald Deibert, John Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski, and Jonathan Zittrain, eds., MIT Press (Cambridge), 2008

- ^ "Internet Filtering: The Politics and Mechanisms of Control" Archived 19 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Jonathan Zittrain and John Palfrey, in Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Ronald Deibert, John Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski, and Jonathan Zittrain, eds., MIT Press (Cambridge), 2008

- ^ "Internet Censorship in China". The New York Times. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (22 January 2012). World Report 2012: China. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ G. King; et al. (22 August 2014). "Reverse-engineering censorship in China: Randomized experimentation and participant observation". Science. 345 (6199): 891. doi:10.1126/science.1251722. PMID 25146296. S2CID 5398090. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "WTO could challenge Internet censorship". Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom. 59 (1). Chicago: American Library Association: 6. January 2010. ProQuest 217137198.

- ^ Kelion, Leo (24 September 2019). "Google wins landmark right to be forgotten case". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Satariano, Adam (3 October 2019). "Facebook Can Be Forced to Delete Content, E.U.'s Top Court Rules". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Cowie, James. "Egypt Leaves the Internet". Renesys. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ a b Kirk, Jeremy (28 January 2011). "With Wired Internet Locked, Egypt Looks to the Sky". IDG News/PC World. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ "Pulling the Plug: A Technical Review of the Internet Shutdown in Burma". opennet.net. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Journalists confined to their hotels, Internet disconnected". Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Skinner, Helena (22 November 2019). "How did Iran's government pull the plug on the Internet?". euronews. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Sudan's Internet Outage". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Sudan internet shows signs of recovery after month-long shutdown". 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Ethiopia partially restores internet access days after blackout following reported Amhara coup attempt". 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Post-election internet shutdown in Mauritania following widespread mobile disruptions". 25 June 2019. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Government that have shut down the Internet in 2019". 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Internet Shutdowns in India". internetshutdowns.in. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ Krishna Mohan, Vaishnavi (30 January 2021). "Internet Shutdowns in India: From Kashmir to Haryana". Global Views 360. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Iraq shuts down internet to prevent cheating in national science exams". 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Internet being restored in Iran after week-long shutdown". NetBlocks. 23 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ a b Ivana Kottasová and Sara Mazloumsaki (19 November 2019). "What makes Iran's internet blackout different". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Iran shuts down country's internet in the wake of fuel protests". TechCrunch. 17 November 2019. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.