Business action on climate change

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Business action on climate change is a topic which since 2000 includes a range of activities relating to climate change, and to influencing political decisions on climate change-related regulation, such as the Kyoto Protocol. Major multinationals have played and to some extent continue to play a significant role in the politics of climate change, especially in the United States, through lobbying of government and funding of climate change deniers. Business also plays a key role in the mitigation of climate change, through decisions to invest in researching and implementing new energy technologies and energy efficiency measures.

Overview

[edit]

Physical risks of climate change top the list of business concerns for US and EU firms.

In 1989 in the US, the petroleum and automotive industries and the National Association of Manufacturers created the Global Climate Coalition (GCC) to oppose mandatory actions to address global warming. In 1997, when the US Senate overwhelmingly passed a resolution against ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, the industry funded a $13 million industry advertising blitz in the run-up to the vote.[4]

In 1998 The New York Times published[5] an American Petroleum Institute (API) memo outlining a strategy aiming to make "recognition of uncertainty ... part of the 'conventional wisdom.'"[6] The memo has been compared to a late 1960s memo by tobacco company Brown and Williamson, which observed: "Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the 'body of fact' that exists in the mind of the general public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy."[7] Those involved in the memo included Jeffrey Salmon, then executive director of the George C. Marshall Institute, Steven Milloy, a prominent denialist commentator, and the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Myron Ebell.[7] In June 2005 a former API lawyer, Philip Cooney, resigned his White House post after accusations of politically motivated tampering with scientific reports.[8]

In 2002, in the wake of both declining membership and President Bush's withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol, the GCC announced that it would "deactivate" itself.[9]

Ex-World Bank economist Herman Daly suggests that neoliberalism and globalisation bring about "a permanent international standard-lowering competition to attract capital".[10] If accurate, this contemporary economic environment therefore also aids businesses who are hostile to action against climate change. They are able to relocate their activities to states which have less climate based regulations.

At the same time, since 1989 many previously denialist petroleum and automobile industry corporations have changed their position as the political and scientific consensus has grown, with the creation of the Kyoto Protocol and the publication of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Second and Third Assessment Reports. These corporations include major petroleum companies like Shell, Texaco and BP, as well as automobile manufacturers like Ford, General Motors and Mercedes-Benz Group. Some of these have joined with the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (formerly the Pew Center on Global Climate Change), a non-profit organization aiming to support efforts to address global climate change.[11]

Since 2000, the Carbon Disclosure Project has been working with major corporations and investors to disclose the emissions of the largest companies. By 2007, the CDP published the emissions data for 2400 of the largest corporations in the world, and represented major institutional investors with $41 trillion combined assets under management.[12] The pressure from these investors had had some success in working with companies to reduce emissions.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development, a CEO-led association of some 200 multinational companies, has called on governments to agree on a global targets, and suggests that it is necessary to cut emissions by 60-80 percent from current levels by 2050.[13]

In 2017, after the election of Donald Trump, backing was shown in the business community for the Paris Agreement, which became effective November 4, 2016.[14]

In 2020 the demand for business action to stop climate change grew steadily. An organisation named "Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures" was created with a specific aim to show which companies are trying to stop climate change and which are not. The Bank of England launched an initiative to identify climate-related financial risks.[15] BP pledged to become carbon neutral by 2050, and the largest finance management company BlackRock said it will not serve those who resist trying to reduce GHG emissions. Investors with a capital of 5 trillion dollars pledged to have 100% fossil free investments by the year 2050.[16]

According to Torsten Lichtenau, leading expert in global carbon transition, there was a peak on business climate action in 2021 - 2022 at the time of COP26, but in 2024 “it’s dropped back to 2019 levels." As for 2024 issues like geopolitics, inflation and artificial intelligence became more important.[17]

Business Coalitions and Initiatives

[edit]Global Climate Coalition

[edit]A central organization in climate denial was the Global Climate Coalition (1989–2002), a group of mainly United States businesses opposing immediate action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The coalition funded deniers with scientific credentials to be public spokespeople, provided industry a voice on climate change and fought the Kyoto Protocol. The New York Times reported that "even as the coalition worked to sway opinion [towards denial], its own scientific and technical experts were advising that the science backing the role of greenhouse gases in global warming could not be refuted."[18]

In the year 2000, the rate of corporate members leaving accelerated when they became the target of a national divestiture campaign run by John Passacantando and Phil Radford with the organization Ozone Action. According to The New York Times, when Ford Motor Company was the first company to leave the coalition, it was "the latest sign of divisions within heavy industry over how to respond to global warming."[19][20] After that, between December 1999 and early March 2000, the GCC was deserted by Daimler-Chrysler, Texaco, the Southern Company and General Motors.[21]

The organization closed in 2002, or in their own words, 'deactivated'.

World Economic Forum

[edit]In the beginning of the 21st century the World Economic Forum began to increasingly deal with environmental issues.[22] In the Davos Manifesto 2020 it is said that a company among other things:

"acts as a steward of the environmental and material universe for future generations. It consciously protects our biosphere and champions a circular, shared and regenerative economy."

"responsibly manages near-term, medium-term and long-term value creation in pursuit of sustainable shareholder returns that do not sacrifice the future for the present."

"is more than an economic unit generating wealth. It fulfils human and societal aspirations as part of the broader social system. Performance must be measured not only on the return to shareholders, but also on how it achieves its environmental, social and good governance objectives."[23][24][25]

The forum launched the Environmental Initiative that covers climate change and water issues. Under the Gleneagles Dialogue on Climate Change, the U.K. government asked the World Economic Forum at the G8 Summit in Gleneagles in 2005 to facilitate a dialogue with the business community to develop recommendations for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This set of recommendations, endorsed by a global group of CEOs, was presented to leaders ahead of the G8 Summit in Toyako and Hokkaido held in July 2008.[26][27]

In January 2017, WEF launched the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE), which is a global public private partnership seeking to scale circular economy innovations.[28][29] PACE is co-chaired by Frans van Houten (CEO of Philips), Naoko Ishii (CEO of the Global Environment Facility, and the head of United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).[30] The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the International Resource Panel, Circle Economy and Accenture serve as knowledge partners.

The Environment and Natural Resource Security Initiative was emphasized for the 2017 meeting to achieve inclusive economic growth and sustainable practices for global industries. With increasing limitations on world trade through national interests and trade barriers, the WEF has moved towards a more sensitive and socially minded approach for global businesses with a focus on the reduction of carbon emissions in China and other large industrial nations.[31][32]

The World Economic Forum is working to eliminate plastic pollution, stating that by the year 2050 it will consume 15% of the global carbon budget and will pass by its weight fishes in the world's oceans. One of the methods is to achieve circular economy.[33][34][35]

The theme of 2020 World Economic Forum annual meeting was "Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World". Climate change and sustainability were central themes of discussion. Many argued that GDP is failed to represent correctly the wellbeing and that fossil fuel subsydies should be stopped. Many of the participants said that a better capitalism is needed. Al Gore summarized the ideas in the conference as: "I don't want to be naive, but I want to acknowledge that the center of the global economy is now saying things that many of us have dreamed they might for a long time," and "The version of capitalism we have today in our world must be reformed".[36][25]

In this meeting the World Economic Forum launched the Trillion Tree Campaign—an initiative aiming to "grow, restore and conserve 1 trillion trees around the world—in a bid to restore biodiversity and help fight climate change". Donald Trump joined the initiative. The forum stated that: "Nature-based solutions—locking-up carbon in the world's forests, grasslands and wetlands—can provide up to one-third of the emissions reductions required by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement targets," adding that the rest should come from the heavy industry, finance and transportation sectors. One of the targets is to unify existing reforestation projects[37][38]

In 2020, the forum published an article in which it claims that the COVID-19 pandemic is linked to the destruction of nature. The number of emerging diseases is rising and this rise is linked to deforestation and species loss. In the article there are multiple examples of the degradation of ecological systems caused by humans. It is also says that half of the global GDP is moderately or largely dependent on nature. The article concludes that the recovery from the pandemic should be linked to nature recovery.[39][40]

In July 2020 the forum published the "Future of Nature and Business Report", saying that "Prioritizing Nature" can give to the global economy 10.1 trillion dollars per year and 395 million jobs by the year 2030.[41]

U.S. Climate Action Partnership

[edit]The U.S. Climate Action Partnership (USCAP) was formed in January 2007 with the primary goal of influencing the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions by the United States. Original members included General Electric, Alcoa, and Natural Resources Defense Council, and they were joined in April 2007 by ConocoPhillips and AIG.

Energy industry

[edit]

Future carbon bombs

[edit]For a 50% probability of limiting global warming by 2050 to 1.5 °C large amounts of fossil fuels would need to be left underground.[42][43] In various nations oil and gas companies such as Qatar Energy, Gazprom and Saudi Aramco are planning new large fossil fuel projects, called "carbon bombs", that would defeat the 1.5 °C climate goal if not "defused" and produce greenhouse gases equivalent to a decade of CO2 emissions from China. Researchers have identified the 425 biggest fossil fuel extraction projects globally, of which 40% as of 2020 are new projects that haven't yet started extraction.[44] As of 2022[update], countries like China and India are planning to boost production of coal and other fossil fuels.[45][46]

ExxonMobil

[edit]ExxonMobil has been a leading figure in the business world's position on climate change, providing substantial funding to a range of global-warming-denialist organizations. Mother Jones counted some 40 ExxonMobil-funded organizations that "either have sought to undermine mainstream scientific findings on global climate change or have maintained affiliations with a small group of 'skeptic' (denialist) scientists who continue to do so." Between 2000 and 2003 these organizations received more than $8m in funding.[7]

It also had a key influence in the Bush administration's energy policy, including on the Kyoto Protocol,[47] supported by both $55 million spent on lobbying since 1999,[7] and direct contacts between the company and leading politicians. It was a leading member of the Global Climate Coalition. It encouraged (and may have been instrumental in) the replacement in 2002 of the head of the IPCC, Robert Watson.[48] It has also invested $100 million into the Global Climate and Energy Project, with Stanford University, and other programs at institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Carnegie Mellon University and the International Energy Agency Greenhouse Gas Research and Development Program.

Some of Exxon's activities on climate change produced strong criticism from environmental groups, including reactions such as a leaflet produced by the Stop Esso campaign, saying 'Don't buy E$$o', and featuring a tiger hand setting fire to the Earth. The company's carbon dioxide emissions are more than 50% higher than those of British rival BP, despite the US firm's oil and gas production being only slightly larger.[49]

According to a 2004 study commissioned by Friends of the Earth, ExxonMobil and its predecessors caused 4.7–5.3% of the world's man-made carbon dioxide emissions between 1882 and 2002. The group suggested that such studies could form the basis for eventual legal action.[50]

ExxonMobil made several modest climate pledges. There are some concerns about the implementation.[51]

In 2021 two and potentially three environmentally-concerned directors were introduced to the board of directors by an activist hedge fund.[52]

BP

[edit]BP left the Global Climate Coalition in 1997 and said that global warming was a problem that had to be dealt with, although it subsequently joined others in lobbying the Australian government not to sign the Kyoto Protocol unless the US did.[53] In March 2002 BP's chief executive, Lord Browne, declared in a speech that global warming was real and that urgent action was needed, saying that "Companies composed of highly skilled and trained people can't live in denial of mounting evidence gathered by hundreds of the most reputable scientists in the world."[54] In 2005 BP was considering testing carbon sequestration in one of its North Sea oil fields, by pumping carbon dioxide into them (and thereby also increasing yields).[55]

BP's American division is a member of the U.S. Climate Action Partnership (USCAP).

BP pledged to become 100% climate neutral by 2050.[16] It also declared that it will increase 10 times the investment in low carbon technology, like Renewable energy by the year 2030, stop searching for oil and gas in new countries, cut its oil and gas production by 40%. After the declaration the share price of the company rose by 7–8%.[56][57]

Shell

[edit]In 2021 Royal Dutch Shell announced that its CO2 emissions peaked in 2018 and its oil production in 2019. The company intends to cut emissions by 6–8% by 2023, 20% by 2030, 45% by 2035 and 100% by 2050.[58]

In 2023 Shell ruled out setting targets to reduce end-user emissions, referred to as Scope 3, which account for about 95 percent of the energy company's greenhouse gas pollution.[59]

Chevron

[edit]In 2021, 61% of Chevron shareholders adopted a resolution calling for reducing its GHG emissions, including for scope 3 emissions, e.g., emissions from suppliers and customers of its products.[52]

Koch Industries

[edit]From 2005 to 2008, Koch Industries donated $5.7 million on political campaigns and $37 million on direct lobbying to support fossil fuel industries. Between 1997 and 2008, Koch Industries donated a total of nearly $48 million to climate opposition groups.[60] According to Greenpeace, Koch Industries is the major source of funds of what Greenpeace calls "climate denial".[61][62] Koch Industries and its subsidiaries spent more than $20 million on lobbying in 2008 and $12.3 million in 2009, according to OpenSecrets, a nonpartisan research group.[63][64]

Others

[edit]American Electric Power, the world's largest private producer of carbon dioxide, said in 2005 that targets for carbon reduction "represent a common-sense approach that can begin the process of lowering emissions along a gradual, cost-effective path." The company complained that "uncertainties over the cost of carbon" made it very difficult to make decisions about capital investment.[65]

DuPont has cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 65% since 1990, saving hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. "Give us a date, tell us how much we need to cut, give us the flexibility to meet the goals, and we'll get it done", Xcel Energy CEO Wayne Brunetti told Business Week in 2004.[66]

Duke Energy, FPL Group, and PG&E Corporation are members of the U.S. Climate Action Partnership (USCAP) (see above).

Total and Royal Dutch Shell pledged to reach zero emission by 2050. Chevron and ExxonMobil made a more modest pledge. There are some concerns about the implementation of the pledges.[51]

The majority of the shareholders of ConocoPhillips and Phillips66 voted for resolutions calling to cut emissions in May 2021.[67]

Transportation

[edit]

A large proportion of carbon dioxide emissions occur because of transportation. Various developments to reduce the energy required or offset the emissions produces have been proposed with some implemented.

Motor vehicles

[edit]Several companies have formed or invested in electric car substitutes for petrol or diesel-powered internal combustion engine automobiles. Starting in 2008, a renaissance in electric vehicle manufacturing occurred due to advances in batteries, and the desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve urban air quality.[69] During the 2010s the electric vehicle industry in China expanded greatly with government support.[70] In the early 2020s tightened European emissions standards squeezed its manufacturers of fossil-fuelled cars.[71]

The Tesla Roadster (2008) is an all-electric sports car, and Tesla also produces the Tesla Model S sedan. Vectrix produces and sells an electric scooter rated for 100 km/h (62 mph).

General Motors announced in the year 2021 that by the year 2035 it will completely stop producing cars powered by diesel and gas and will become carbon neutral by 2040.[72]

Personal rapid transit

[edit]There has also been greatly increased interest in personal rapid transit, which applies system engineering principles to reduce energy use, eliminate traffic jams, and produce an acceptable substitute to replace cars, all at the same time. Most systems fully meet Kyoto Treaty carbon emission goals now, 60 years ahead of schedule. Korean steel maker POSCO and its partner Vectus Ltd. have produced a working safety case, including test track and vehicles, that remains fully functional in Swedish winters. A system was installed Suncheon, South Korea.[73] Advanced Transportation Systems' ULTra passed safety certification by the UK Rail Inspectorate in 2003, and built a project at Heathrow Airport connecting one terminal to a remote car park which opened 2010. ATS Ltd. estimates its ULTra PRT will consume 839 BTU per passenger mile (0.55 MJ per passenger km).[74][75] By comparison, automobiles consume 3,496 BTU, and personal trucks consume 4,329 BTU per passenger mile.[76] 2getthere Inc. sells automated electric freight handling and transit vehicles designed to share existing rights of way with normal traffic.[77] The company installed the personal rapid transit system at Masdar in the United Arab Emirates.[78]

Despite numerous proposals no large scale PRT systems have been implemented.

Passenger aviation

[edit]JetBlue announced a plan to become carbon neutral on domestic flights in the US through use of carbon offsets, with longterm plans including the possibility of alternative fuels and other technologies. However, the International Air Transport Association reports that such alternative fuels are in short supply as of January 2020.[79]

Banks

[edit]In 2021 the BNDES (National Bank for Economic and Social Development) in Brazil declared that it will not support more coal thermal power stations and projects related to them. The bank wants to take actions in a similar direction in other sectors of the economy. The bank is considered as the "least worst" from all the banks of Brazil according to Responsible Banking Guide.[80]

Nonetheless, many other major banks have continued to fund the development of fossil fuels instead of climate change mitigation.[81]

Insurance industry

[edit]In 2004 Swiss Re, the world's second largest reinsurance company, warned that the economic costs of climate-related disasters threatened to reach $150 billion a year within ten years.[82]

In 2006 Lloyd's of London, published a report highlighting the latest science and implications for the insurance industry.[83]

Swiss Re has said that if the shore communities of four Gulf Coast states choose not to implement adaptation strategies, they could see annual climate-change related damages jump 65 percent a year to $23 billion by 2030. "Society needs to reduce its vulnerability to climate risks, and as long as they remain manageable, they remain insurable, which is our interest as well," said Mark D. Way, head of Swiss Re's sustainable development for the Americas.[84][85]

AIG is a member of the U.S. Climate Action Partnership (USCAP) (see above).

Zurich Insurance Group, according to Ben Harper, the head of the sustainability unit in the North American section of the company, has a program for reducing its carbon footprint: make the facilities 100% renewables in a few years, reduce the use of paper by 80%, stop using single-use plastic, invest $4.6 billion in green and social projects. The company already has many green products and services and want to make more. The work on the implementation was not stopped at the time of Coronavirus disease 2019 and the pandemic may result even in higher ecological consciousness, among other it increase demand for ecological products, walking, biking, simple living.[86] The company was the leading insurer of the Trans Mountain pipeline, but stopped supporting it, in July 2020.[87]

Media

[edit]In the UK, some newspapers (Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph) are significantly anti-science, while most others (with varying enthusiasm, The Independent giving it most prominence) support action on global warming. Overall, British newspapers have given the issue three times more coverage than US newspapers.[88] In 2006 (British Sky Broadcasting (Sky) became the world's first media company to go 'climate neutral' by purchasing enough carbon offsets. The CEO of the company James Murdoch (son of Rupert Murdoch and heir apparent for the News International empire) is a strong advocate of action on climate change and is thought to be influential on the issue within the wider group of companies.[citation needed] In June 2006, to much industry interest, Rupert Murdoch invited Al Gore to make his climate change presentation at the annual News Corp (including the Fox Network) gathering at the Pebble Beach golf resort, (USA).[89] In August 2007, Rupert Murdoch announced plans for News Corp. to be carbon neutral by 2010.[90]

Facebook announced in 2021 that it will make efforts to stop disinformation about climate change. The company will use George Mason University, Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the University of Cambridge as sources of information. The company will expand its information hub on climate to 16 countries. Users in others countries will be directed to the site of the United Nations Environment Programme for information.[91]

Finance management

[edit]Black Rock

[edit]In January 2020 BlackRock, the largest finance management company in the world, announced that it would begin divestment from thermal coal and take other measures to make its assets more sustainable. Other companies that made similar statements include "Goldman Sachs, Liberty Mutual,... the Hartford Financial Services Group, Inc., ... and the European Investment Bank—the largest international public bank in the world "[92]

JP Morgan

[edit]The company is the biggest investor in fossil fuels in the world, therefore many try to persuade it to take climate action. In 2017 the company committed to giving 200 billion dollars to clean finance by 2025 and take 100% of its energy from renewables by the end of 2020. It expects to reach both targets. In 2020 the company pledged to give 200 billion to support climate action and reaching Sustainable Development Goals in the year 2020, expand the restriction on investment in coal and stop investment in arctic oil and gas drilling, create a more sustainable investment portfolio, join the climate action 100+ coalition. It did not pledge to stop investments in tar sands, fracking and other fossil fuels.[93][94]

In October 2020 JPMorgan Chase declared that it began to work on achieving carbon neutrality by 2050.[95]

Despite its promises to reduce emissions, JPMorgan Chase still has invested heavily in fossil fuels.[96] In 2021 they invested around US$62 billion in fossil fuels.[97] This brings JPMorgan Chase to a total of nearly US$382 billion invested in fossil fuels since 2016.[97] There has been some green project investments, but they are a third of the revenue the banking firm has made from fossil fuels.[98]

In light of the IPCC 2022 report climate scientists took action and protested fossil fuel investments on a global scale.[99][100] In LA Climate Scientists chose the JP Morgan building due to JPMorgan Case heavy investment in fossil fuels.[99][101] These scientists were met with a swarm of police and later arrested after chaining themselves to the front doors and blocking the entrance.[99][101]

HSBC

[edit]In October 2020, HSBC, the biggest bank in Europe, committed to achieve zero emission by 2050, e.g., by this year it would not only become carbon neutral by itself but also will work only with carbon neutral clients. It also committed to provide 750–1,000 billion dollars to help clients make the transition. It also pledged to achieve carbon neutrality in his own operations by 2030.[102]

Fashion industry

[edit]

The fashion industry is one of the largest polluters, producing around 8-10% of all greenhouse gas emissions.[104] Fast fashion culture and mass production of lower quality, less durable materials have contributed to a greater impact.[104] Some retailers have explored ways to reduce the carbon footprint, water use and energy use of garment production. Examples include integrating recycled materials into garments.[104]

In 2022 Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard gave away the company, with all profits going to a non-profit entity funding climate change activism.[105][106]

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs)

[edit]Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) play a crucial role in addressing climate change, as they represent around 13% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[107] However, SMEs often face unique challenges in implementing climate action strategies, including limited resources and expertise, lack of awareness about climate change impacts, financial constraints for implementing green technologies, and difficulty accessing information on best practices.[108]

Despite these challenges, SMEs also have opportunities to benefit from climate action through increased energy and resource efficiency, reduced operational costs, access to new markets for green products and services, enhanced reputation and competitiveness, and improved resilience to climate-related risks.[109]

Research indicates that effective policy approaches for encouraging SME climate action include targeted financial incentives and grants, provision of technical assistance and capacity building, development of sector-specific guidance and tools, and creation of networks and partnerships to share best practices.[110]

Key strategies

[edit]

Businesses take action on climate change for several reasons. Action improves corporate image and better aligns corporate actions with the environmental interests of owners, employees, suppliers, and customers. Action also occurs to reduce costs, increase return on investments, and to reduce dependency on uncontrollable costs.

Increased energy efficiency

[edit]

For many companies, looking at more efficient energy use can pay off in the medium to long term; unfortunately, shareholders need to be satisfied in the short term, so regulatory intervention is often required, to encourage prudent conservation measures. However, as carbon intensity starts to show up on balance books through organizations such as the Carbon Disclosure Project, voluntary action is starting to take place.

Recently[when?] there has been a spate of companies acting to improve their energy efficiency. Possibly the most prominent of these companies is Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart, the largest retailer in the US, has announced specific environmental goals to reduce energy use in its stores and pressure its 60,000 suppliers in its worldwide supply chain to follow its lead. On energy efficiency, Wal-Mart wants to increase the fuel efficiency of its truck fleet by 25% over the next three years and double it within ten years. By 2020, it is expected to save the company $494 million a year.

The company also wants to build a store that is at least 25% more energy efficient within four years.

Use of renewable energies

[edit]In August 2002, the largest gathering of ministers in the history of the world met at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg.[112] The global environmental community discussed the role of renewables and energy efficiency in lowering carbon emissions, mitigating poverty reduction (energy access) and improving energy security. One result from WSSD was the formation of to carry forward the international dialogue on sustainable energy and its role in the energy mix.[113]

Partnerships formed include the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership, the Global Village Energy Partnership, the Johannesburg Renewable Energy Coalition (JREC), and the Global Network on Energy for Sustainable Development.[114][115][116]

Renewable energies and renewable energy technologies have many advantages over their fossil fuel counterparts. These advantages include the absence of local pollution such as particulates, sulfur oxides (SOX's) and nitrous oxides (NOX's). For the business community, the economic advantages are also becoming clearer. Numerous studies have shown that the working environment has a significant effect on workforce morale. Renewable energy solutions are a part of this, wind turbines in particular being seen by many as a potent symbol of a new modernity, where environmental considerations are taken seriously. A workforce seeing a forward-looking and responsible company is more likely to feel good about working for such a company. A happier workforce is a more productive workforce.

More directly, the high petroleum (oil) and gas prices of 2005 have only added to the attraction of renewable energy sources. Although most renewable energies are more expensive at current fuel prices, the difference is narrowing, and uncertainty in oil and gas markets is a factor worth considering for highly energy-intensive businesses.

Another factor affecting the uptake of renewable energies in Europe is the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS or EUTS). Many large businesses are fined for increases in emissions, but can sell any "excess" reductions they make.

Companies with high-profile renewable energy portfolios include an aluminium smelter (Alcan), a cement company (Lafarge), and a microchip manufacturer (Intel). Many examples of corporate leadership in this area can be found on the website of The Climate Group, an independent organization set up for promoting such action by business and government.

Carbon offsets

[edit]The principle of carbon offset is fairly simple: a business decides that it does not want to contribute further to global warming, and it has already made efforts to reduce its carbon (dioxide) emissions, so it decides to pay someone else to further reduce its net emissions by planting trees or by taking up low-carbon technologies. Every unit of carbon that is absorbed by trees—or not emitted due to funding of renewable energy deployment—offsets the emissions from fossil fuel use. In many cases, funding of renewable energy, energy efficiency, or tree planting—particularly in developing nations—can be a relatively cheap way of making an event, project, or business "carbon neutral". Many carbon offset providers—some as inexpensive as $0.10 per ton of carbon dioxide—are referenced in the carbon offset article of this encyclopedia.

Many businesses are now looking to carbon offset all their work. An example of a business going carbon neutral is FIFA: their 2006 World Cup Final will be carbon neutral. FIFA estimate they are offsetting one hundred thousand tons of carbon dioxide created by the event, largely as a result of people travelling there. Other carbon neutral companies include the bank HSBC, the consumer staples manufacturer Annie's Homegrown, world leading society publisher Blackwell Publishing, and the publishing house New Society Publishers. The Guardian also offsets its carbon emissions resulting from international air travel.

Many companies are trying to achieve carbon offsets by nature-based solutions like reforestation, including mangrove forests and soil restoration. Among them Microsoft, Eni. Increasing the forest cover of Earth by 25% will offset the human emissions in the latest 20 years. In any case it will be necessary to pull from the atmosphere the CO2 that already have been emitted. However, it can work only if the companies will stop to pump new emissions to the atmosphere and stop deforestation.[117]

Carbon projects

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

A carbon project refers to a business initiative that receives funding because it will result in a reduction in the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs). To prove that the project will result in real, permanent, verifiable reductions in greenhouse gases, proof must be provided in the form of a project design document and activity reports validated by an approved third party.

Reasons for carbon project development

Carbon projects are developed for reasons of voluntary environmental stewardship, as well as legal compliance under an emissions trading program. Voluntary carbon (GHG) reducers may wish to monetize reductions in their carbon footprint by trading the reductions in exchange for monetary compensation. The transfer of environmental stewardship rights would then allow another entity to make an environmental stewardship claim. There are several developing voluntary reduction standards that projects can use as guides for development.

Kyoto Protocol

Carbon projects have become increasingly important since the advent of emissions trading under Phase I of the Kyoto Protocol in 2005. They may be used if the project has been validated by a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) Designated Operational Entity (DOE) according to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The resulting emissions reductions may become Certified Emissions Reductions (CERs) when a DOE has produced a verification report which has been submitted to the CDM Executive Board (EB).

There may be new project methodology validated by the CDM EB for post phase II Kyoto trading.

United States

In the United States, standards similar to those of the Kyoto Protocol schemes are developing around California's AB-32 and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). Offset projects can be of many types, but only those that have proven additionality are likely to become monetized under a future US Cap & Trade program.

One example of such a project, the Valley Wood Carbon Sequestration Project, receives funding from a partnership that was developed by Verus Carbon Neutral that linked 17 merchants of Atlanta's Virginia-Highland shopping and dining neighborhood retail district, through the Chicago Climate Exchange, to directly fund thousands of acres of forest in rural Georgia. The unique partnership established Virginia-Highland as the first Carbon-Neutral Zone in the United States.[118][119]

Operation

An entity whose greenhouse gas emissions are capped by a regulatory program has three choices for complying if they exceed their cap. First, they could pay an alternative compliance measure or "carbon tax", a default payment set by the regulatory body. This choice is usually the least attractive given the ability to comply by trading.[citation needed]

The second option is to purchase carbon credits[120] within an emissions trading scheme.[121] The trade provides an economic disincentive to the polluter, while providing an incentive to the less polluting organisation. As fossil fuel generation becomes less attractive it will be increasingly unattractive to exceed a carbon cap because the financial disincentive will grow via market forces. The price of a carbon allowance would go up because supply would decline while demand stays constant (assuming a positive growth rate for energy consumption).

The final option is to invest in a carbon project. The carbon project will result in a greenhouse gas emission reduction which can be used to offset the excess emissions generated by the polluter. The financial disincentive to pollute is in the form of the capital expenditure to develop the project or the cost of purchasing the offset from the developer of the project. In this case the financial incentive would go to the owner of the carbon project.

Project selection

The most important part of developing a carbon project is establishing and documenting the additionality of the project—that the carbon project would not have otherwise occurred. It is also essential to document the measurement and the verification methodology applied, as outlined in the project development document.

Developing a carbon project is appropriate for renewable energy projects such as wind power, solar power, low impact-small hydropower, biomass, and biogas. Projects have also been developed for a wide variety of other emissions reductions such as reforestation, fuel switching (i.e. to carbon-neutral fuels and carbon-negative fuels), carbon capture and storage, and energy efficiency.

Barriers to investments

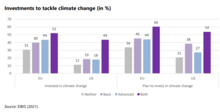

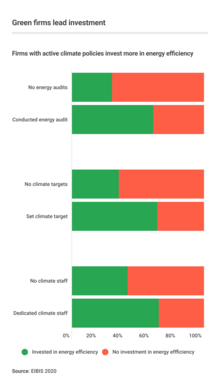

[edit]The European Investment Bank's investment survey 2021 found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change was addressed by 43% of EU enterprises. Despite the pandemic's effect on businesses, the percentage of firms planning climate-related investment rose to 47%. This was a rise from 2020, when the percentage of climate related investment was at 41%.[122][123] In 2021, firms' investments in climate change mitigation were being hampered by uncertainty about the regulatory environment and taxation.[122][124]

See also

[edit]- Business for Innovative Climate and Energy Policy

- Carbon emission trading

- Carbon offset

- Climate change mitigation

- Eco-investing

- Ecological economics

- Economics of global warming

- Ecotax

- Environmental economics

- ExxonMobil climate change controversy

- Fossil fuels lobby

- Individual action on climate change

- Low-carbon economy

- Personal carbon trading

- Politics of climate change

- Sustainable business

- Sustainable finance

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Firms brace for climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (2021). EIB Investment Report 2020/2021: Building a smart and green Europe in the COVID-19 era. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-9286148118.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (2022). EIB Investment Report 2021/2022: Recovery as a springboard for change. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-9286151552.

- ^ "Snowed". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "Industrial Group Plans to Battle Climate Treaty", The New York Times, March 26, 1998. Accessed 26 June 2018.

- ^ "Global Science Communications" (PDF). April 3, 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2007. Also available here and here

- ^ a b c d "Some Like It Hot". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Borger, Julian (2005-06-09). "Ex-oil lobbyist watered down US climate research | Environment". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ May, Bob (January 27, 2005). "Under-informed, over here". The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Pearce, Fred. "Review: How green are the multinationals?". New Scientist. Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- ^ "Business Environmental Leadership Council (BELC) Member Companies". Archived February 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Carbon Disclosure Project: Homepage". Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ WBCSD (2007-09-05). "Climate Change Debate Needs Revolution, Financial Times, 5 September 2007". Wbcsd.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Amy Harder (April 17, 2017). "Corporate America isn't backing Trump on climate". AXIOS.com. AXIOS Media. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Woods, Sam (2020) Open Letter BoE

- ^ a b Shukman, David (27 February 2020). "Climate change: Pressure on big investors to act on environment". BBC News. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Khan, Yusuf (9 September 2024). "Sustainability Is Falling on the CEO To-Do List. Customers Still See It as a Priority". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Revkin, Andrew C. Industry Ignored Its Scientists on Climate, The New York Times. April 23, 2009.

- ^ "Canvassing Works". Canvassing Works. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (7 December 1999). "Ford Announces Its Withdrawal From Global Climate Coalition". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ^ "GCC Suffers Technical Knockout, Industry defections decimate Global Climate Coalition". June 2022.

- ^ "Environment and Natural Resource Security". weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus (2 December 2019). "Davos Manifesto 2020: The Universal Purpose of a Company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution". weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Why we need the "Davos Manifesto" for a better kind of capitalism … The Universal Purpose of a Company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution". Peter Fisk. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b Wu, Tim (23 January 2020). "The Revolution Comes to Davos". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Black, Richard (20 June 2008). "Business Chiefs Urge Carbon Curbs" Archived 23 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine BBC News. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Szabo, Michael (19 June 2008). "Business Chiefs Call for G8 Climate Leadership" Archived 31 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Reuters. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Circular Economy". weforum.org. World Economic Forum.

- ^ "TopLink". toplink.weforum.org.

- ^ "Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy". Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy.

- ^ Shaping the Future of Environment and Natural Resource Security The World Economic Forum Davos 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "System Initiative on Shaping the Future of Environment and Natural Resource Security". InforMEA. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Kristin (24 September 2019). "3 ways we are making an impact on plastic pollution". weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Rooney, Katharine (22 January 2020). "The story of two brothers who travelled through a river of trash and inspired a nation". weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Sean (6 February 2020). "This man ran across the USA to raise awareness of plastic pollution". The European Sting. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ WORLAND, JUSTIN (27 January 2020). "How Davos Became a Climate Change Conference". Times. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Pomeroy, Robin (22 January 2020). "One trillion trees - World Economic Forum launches plan to help nature and the climate". weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Long, Heather (24 January 2020). "Davos elite want to plant 1 trillion trees to help the planet, but many still fight a carbon tax". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Quinney, Marie (14 April 2020). "COVID-19 and nature are linked. So should be the recovery". weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Updates on COVID-19 and the environment". Geneva Environment Network. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ White, Kimberly (20 August 2020). "New WEF Report Says 'Prioritizing Nature' Is A $10 Trillion Opportunity That Would Create 395 Million Jobs". Green Queen. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "How much of the world's oil needs to stay in the ground?". The Guardian. 8 September 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Welsby, Dan; Price, James; Pye, Steve; Ekins, Paul (September 2021). "Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world". Nature. 597 (7875): 230–234. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..230W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03821-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34497394. S2CID 237455006.

- ^ Kühne, Kjell; Bartsch, Nils; Tate, Ryan Driskell; Higson, Julia; Habet, André (1 July 2022). ""Carbon Bombs" – Mapping key fossil fuel projects". Energy Policy. 166: 112950. Bibcode:2022EnPol.16612950K. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112950. ISSN 0301-4215. S2CID 248756651.

- News article: Taylor, Damian Carrington Matthew. "Revealed: the 'carbon bombs' set to trigger catastrophic climate breakdown". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Pandemic, war, politics hamper global push for climate action". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Tate, Ryan Driskell (23 May 2022). Why China's Coal Mine Boom Jeopardizes Short-Term Climate Targets (PDF) (Report). Global Energy Monitor.

- ^ "Revealed: how oil giant influenced Bush | World news". The Guardian. London. 2005-06-08. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "Climate Change – Addressing the Risks of Climate Change: ExxonMobil's Views and Actions". ExxonMobil. Archived from the original on December 18, 2007.

- ^ MacAlister, Terry (2004-10-07). "Exxon admits greenhouse gas increase | Environment". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "Friends of the Earth: Archived press release: ExxonMobil's contribution to global warming revealed". Friends of the Earth (EWNI) foe.co.uk. 2004-01-29. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ a b Kusnetz, Nicholas (16 July 2020). "What Does Net Zero Emissions Mean for Big Oil? Not What You'd Think". Inside Climate News. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ a b Peel, Jacqueline; Neville, Ben; Markey-Towler, Rebekkah (31 May 2021). "Four seismic climate wins show Big Oil, Gas and Coal are running out of places to hide". The Conversation. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Environmentalists and corporate reputation management". Uow.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2009-02-11. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ mindfully.org (2001-02-13). "How Green Is BP? DARCY FREY / The New York Times 8dec02". Mindfully.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ McKie, Robin (2005-04-25). "Seabed supplies a cure for global warming crisis | Science | The Observer". Observer.guardian.co.uk. London. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Davidson, Jordan (5 August 2020). "BP to Cut Oil and Gas Production 40%, Invest 10x More in Green Energy". Ecowatch. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Ziady, Hanna (4 August 2020). "BP will slash oil production by 40% and pour billions into green energy". CNN. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (11 February 2021). "Shell Claims It Reached Peak Oil Production in 2019". Ecowatch. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Bousso, Ron; Nasralla, Shadia (16 March 2023). "Shell rules out more ambitious goal for end-user emissions". Reuters. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Vidal, John (30 March 2010). "US oil company donated millions to climate sceptic groups, says Greenpeace". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Secretly Funding the Climate Denial Machine". Global Warming. Washington: Greenpeace. 2010-03-29. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ DeMelle, Brendan (2010-03-30). "Greenpeace Unmasks Koch Industries' Funding of Climate Denial Industry". Los Angeles: Huffington Post.

- ^ "Client Profile: Summary, 2008". OpenSecrets.

- ^ "Client Profile: Summary, 2009". OpenSecrets.

- ^ "Global Inc. Goes Green". Mother Jones. 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "BW Online | August 16, 2004 | Global Warming". Businessweek.com. 2004-08-16. Archived from the original on August 8, 2004. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "61% of Chevron shareholders support Follow This climate resolution". Follow this. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (2021-05-31). The EIB Climate Survey 2020-2021 - The climate crisis in a COVID-19 world: calls for a green recovery. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5021-0.

- ^ David B. Sandalow, ed. (2009). Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington? (1st. ed.). The Brookings Institution. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-8157-0305-1. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2011.See Introduction

- ^ "DRIVING A GREEN FUTURE: A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CHINA'S ELECTRIC VEHICLE DEVELOPMENT AND OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-17.

- ^ "EU proposes effective ban for new fossil-fuel cars from 2035". Reuters. 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- ^ BALDWIN, ROBERTO (29 January 2021). "GM Announces Goal to Eliminate Gas and Diesel Vehicles by 2035". Car and driver. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "POSCO signs MOU with Suncheon City Government for Asia's first Personal Rapid Transit System". Vectusprt.com. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Lowson, Martin (2004). "A New Approach to Sustainable Transport Systems". Archived from the original (DOC) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ The conversion is: 0.55 MJ = 521.6 BTU; 1.609 km = 1 mi; therefore, 521.6 x 1.609 = 839

- ^ "Transportation Energy Databook, 26th Edition, Ch. 2, Table 2-12". U.S. Dept. of Energy. 2004.

- ^ "2getthere web site" (in Dutch). 2getthere.eu. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Mogge, John, The Technology of Personal Transit, "Figure 6. MASDAR Phase 1A Prototype Passenger PRT." Paper delivered at the World Future Energy Summit, January 20, 2009. Available in WFES online media center.

- ^ Shivdas, Sanjana (6 January 2020). "JetBlue to become carbon neutral in 2020". Reuters. Bengaluru. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Bye bye, coal: BNDES finally leaves the dirty mineral behind". 350.org. Capital Reset. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "These banks have poured trillions of euros into fossil fuel expansion". euronews. 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "911 in New Orleans". Mother Jones. 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ ""Climate Change - Adapt or Bust"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-07-21. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ US Gulf Coast could face average annual losses of up to US$23 billion by 2030 and cumulative economic damages of $350 billion from climate risks, says Swiss Re research Archived 2018-07-31 at the Wayback Machine; 20 October 2010

- ^ A City Prepares for a Warm Long-Term Forecast in The New York Times May 2011

- ^ Jergler, Don (16 July 2020). "Zurich NA Sustainability Head: Pandemic is a Roadmap for Climate Change Battle". Insurance Journal. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (23 July 2020). "Trans Mountain Pipeline's Lead Insurer Zurich Drops Coverage". Ecowatch. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Ross Gelbspan (May 2005). "Snowed". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ Emiko Terazono (6 October 2006). "Gore and Murdoch join forces in TV deal". Financial Times. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ Marc Gunther (27 August 2007). "Rupert Murdoch's climate crusade". CNN. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ Rodriguez, Salvador (18 February 2021). "Facebook will debunk myths about climate change, stepping further into 'arbiter of truth' role". CNBC. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (16 January 2020). "Citing Climate Change, BlackRock Will Start Moving Away from Fossil Fuels". The New Yorker. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ "JPMorgan Chase Expands Commitment to Low-Carbon Economy and Clean Energy Transition to Advance Sustainable Development Goals". JPMorgan Chase and Co. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Wetli, Patty (29 February 2020). "JP Morgan Chase Pulls Back on Lending to Oil, Gas and Coal Companies — Too Little, Too Late?". WTTW. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "JPMorgan aims to back clients to align with Paris climate pact". Reuters. 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Collins (l_collins), Leigh (2021-05-13). "World's leading fossil-fuel financier JP Morgan vows to boost renewables funding | Recharge". Recharge | Latest renewable energy news. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ a b "Banking on Climate Chaos 2022". Banking on Climate Chaos. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ "Big Banks Haven't Quit Fossil Fuel, With $4 Trillion Since Paris". Bloomberg.com. 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ a b c McFall-Johnsen, Morgan. "NASA scientist arrested after chaining himself to Chase Bank as part of global climate protests". Business Insider. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ "Climate scientists are desperate: we're crying, begging and getting arrested | Peter Kalmus". the Guardian. 2022-04-06. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ a b ""We are heading towards a F*** catastrophe," NASA climate scientist breaks down as he chains self to JPMorgan building's door-WATCH". TimesNow. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ White, Lawrence; Cruise, Sinead; Jessop, Simon (9 October 2020). "CORRECTED-EXCLUSIVE-HSBC targets net zero emissions by 2050, earmarks $1 trln green financing". Reuters. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Yes, Those "Vote the Assholes Out" Patagonia Tags Are Real". GQ. 2020-09-16. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ a b c Ro, Christine. "Can fashion ever be sustainable?". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ^ Gelles, David (2022-09-14). "Billionaire No More: Patagonia Founder Gives Away the Company". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ Aratani, Lauren (2023-03-12). "'We've lost the right to be pessimistic': Patagonia treads fine line tackling climate crisis as for-profit company". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ IEA (2015). "Policy Pathway - Accelerating Energy Efficiency in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises 2015 – Analysis" (PDF). IEA. Paris. Retrieved 2024-10-09.

- ^ Blundel, Richard; Hampton, Sam (6 July 2021). "How Can SMEs Contribute to Net Zero?: An Evidence Review". Enterprise Research Centre. Retrieved 2024-10-09.

- ^ OECD (2021). No net zero without SMEs: Exploring the key issues for greening SMEs and green entrepreneurship (Report). Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/bab63915-en. ISSN 2616-4353.

- ^ ERIA/OECD (2024). "SME Policy Index ASEAN 2024 Enabling Sustainable Growth and Digitalisation". www.eria.org. Retrieved 2024-10-11.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (2022-05-05). Digitalisation in Europe 2021-2022: Evidence from the EIB Investment Survey. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5233-7.

- ^ "WSSD". www.iisd.ca. Archived from the original on 2006-11-13.

- ^ "Partnerships for Sustainable Development". www.un.org.

- ^ "Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP)". Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP). Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ "GVEP". www.gvep.org. Archived from the original on 2006-11-07.

- ^ "Home - Global Network on Energy for Sustainable Development". www.gnesd.org. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Hook, Leslie (28 July 2020). "Business turns to nature to fight climate change". Financial Times. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Jay, Kate (November 14, 2008). "First Carbon Neutral Zone Created in the United States". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 7, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Auchmutey, Jim (January 26, 2009). "Trying on carbon-neutral trend". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ "FAQ about Offsetting & the Voluntary Carbon Market". www.act4.io. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Richardson, Andreas; Xu, Jiahua (2020), Pardalos, Panos; Kotsireas, Ilias; Guo, Yike; Knottenbelt, William (eds.), "Carbon Trading with Blockchain", Mathematical Research for Blockchain Economy, Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 105–124, arXiv:2005.02474, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53356-4_7, ISBN 978-3-030-53355-7, S2CID 218516785, retrieved 2021-01-05

- ^ a b Bank, European Investment (2022). EIB Investment Report 2021/2022: Recovery as a springboard for change. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-9286151552.

- ^ "Latest EIB survey: The state of EU business investment 2021". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ^ "Tax Policy and Climate Change" (PDF). Tax Policy and Climate Change.

External links

[edit]References

[edit]- Ross Gelbspan, Boiling Point: How Politicians, Big Oil and Coal, Journalists and Activists Are Fueling the Climate Crisis—And What We Can Do to Avert Disaster, Basic Books, (August 1, 2004) ISBN 0-465-02761-X

- Lowe, EA and Harris, RJ (1998), "Taking Climate Change Seriously: British Petroleum's business strategy", Corporate Environmental Strategy, Winter 1998