Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

Participants Ruled Unconstitutional | |

| Abbreviation | RGGI or ReGGIe |

|---|---|

| Established | 2009 |

| Type | Intergovernmental organization |

| Purpose | Combating global warming |

| Headquarters | New York, NY |

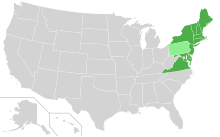

Membership | Participants: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia |

| Website | www |

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI, pronounced "Reggie") is the first mandatory market-based program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by the United States. RGGI is a cooperative effort among the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia to cap and reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the power sector.[1] RGGI compliance obligations apply to fossil-fueled power plants 25 megawatts (MW) and larger within the 11-state region.[2] Pennsylvania's participation in the RGGI cooperative was ruled unconstitutional on November 1, 2023,[3] although that decision has been appealed.[4] North Carolina's entrance into RGGI has been blocked by the enactment of the state's fiscal year 2023–25 budget.[5]

RGGI establishes a regional cap on the amount of CO2 pollution that power plants can emit by issuing a limited number of tradable CO2 allowances. Each allowance represents an authorization for a regulated power plant to emit one short ton of CO2. Individual CO2 budget trading programs in each RGGI state together create a regional market for CO2 allowances.[6]

The RGGI states distribute over 90 percent of allowances through quarterly auctions.[7] These allowance auctions generate proceeds, which participating states are able to invest in strategic energy and consumer benefit programs. Programs funded through RGGI have included energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy, greenhouse gas abatement, and direct bill assistance.

An initial milestone program's development occurred in 2005, when seven states signed a memorandum of understanding announcing an agreement to implement RGGI.[8] The RGGI states then established individual CO2 budget trading programs, based on the RGGI Model Rule.[9] The first pre-compliance RGGI auction took place in September 2008, and the program became effective on January 1, 2009. The RGGI program is currently in its fifth three-year compliance period, which began January 1, 2021.[10]

Track record and benefits

[edit]RGGI states have reduced their carbon emissions while still experiencing economic growth. Power sector carbon emissions in the RGGI states have declined by over 50% since the program began.[11] Media have reported on RGGI's success as a nationally relevant example showing that economic growth can coincide with pollution reductions.[12][13][14] In a report on RGGI, the Congressional Research Service has also said that, "experiences in RGGI may be instructive for policymakers seeking to craft a national program."[15]

While multiple factors contribute to emissions trends, a 2015 peer-reviewed study found that RGGI has contributed significantly to the decline in emissions in the nine-state region.[16] Alternate factors considered by the study included state Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) programs, economic trends, and natural gas prices.

Other independent reports have analyzed RGGI's economic impact. For example, two reports by the Analysis Group studied RGGI's first and second three-year compliance periods. They found that the effects of RGGI's first three years are generating in $1.6 billion in net economic benefit and 16,000 job-years,[17] and RGGI's second three years are generating $1.3 billion in net economic benefit and 14,700 job-years.[18] These figures do not include co-benefits such as public health improvements or avoided climate change impacts.

A Clean Air Task Force (CATF) study investigated public health benefits arising from the RGGI states' shift to cleaner power generation.[19] The study found that the RGGI states transition to cleaner energy is saving hundreds of lives, preventing thousands of asthma attacks and reducing medical impacts and expenses by billions of dollars.

Projected benefits in Pennsylvania

[edit]Environmental

[edit]RGGI has the potential to lower Pennsylvania's emissions of many pollutants dramatically.

- Carbon pollution would be reduced between 97 and 227 million tons[20]

- Nitrogen Oxide would be reduced about 112,000 tons[20]

- Sulfur Dioxide pollution would be reduced 67,000 tons[20]

Health

[edit]The reduction in state air pollution can potentially result in significant health benefits through 2030.

Economic

[edit]The adoption of RGGI also has the potential to provide economic benefits through an increase in jobs, personal income, and $2 billion in gross state product through 2030.[20]

RGGI market

[edit]The highs and lows of the RGGI market can be largely attributed to declining emissions and allowance oversupply, price controls, policy intervention, and the Clean Power Plan of 2015 by the Obama Administration.[21] RGGI has faced its fair share of obstacles, like any other emissions trading program; one of these is an oversupplied market. The oversupplied market related to RGGI can be traced back to the transition from coal to natural gas as well as a weak economy during the time of implementation. Because RGGI has a low price floor, there is no scarcity of allowances. In the world of carbon offset credits, allowances are shared through a cap-and-trade system to limit harmful emissions and catalyze pollution cuts. This cap-and-trade system is proving successful globally as countries are allowed to set more ambitious climate goals and countries across the world are seeing downward trends in emissions.[22]

Key trends

[edit]RGGI states have witnessed positive economic activity and a decrease in emissions, electricity prices, and coal generation. According to RGGI's 2018 Electricity Monitoring report, carbon dioxide emissions decreased by 48.3 percent between the 2006 to 2008 period and the 2016 to 2018 period.[23] Electricity generation from coal decreased significantly since the inception of RGGI, while natural gas and renewable generation increased.[24] RGGI also induces a downward pressure on wholesale electricity prices through investments in state-level energy efficiency programs.[25] These programs, along with other associated RGGI measures, have helped provide positive economic impacts in the RGGI region—the RGGI program provided $1.4 billion in net positive economic activity between 2015 and 2017.[25]

RGGI caps

[edit]The RGGI CO2 cap is the regional cap on power sector emissions.[26] The RGGI states included two interim adjustments to the RGGI cap to account for banked CO2 allowances. The cap declined 2.5 percent each year until 2020. Initial reductions were planned as follows:[27]

The RGGI caps and adjusted caps decreased annually from 2014 to 2020, except in 2020 given the addition of New Jersey.[26][28]

| Year | Base Cap (Tons of CO2) | Adjusted cap |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 91,000,000 | 82,792,336 |

| 2015 | 88,725,000 | 66,833,592 |

| 2016 | 86,506,875 | 64,615,467 |

| 2017 | 84,344,203 | 62,452,795 |

| 2018 | 82,235,598 | 60,344,190 |

| 2019 | 80,179,708 | 58,288,301 |

| 2020 | 96,175,215 | 74,283,807 |

In 2017, the participating states agreed to further reductions in the regional cap, specifying a 30 percent reduction from 2020 to 2030.[29] The new caps for 2021–2030 are as follows:[29]

| Year | Base Cap (Tons of CO2) |

|---|---|

| 2021 | 75,147,784 |

| 2022 | 72,872,784 |

| 2023 | 70,597,784 |

| 2024 | 68,322,784 |

| 2025 | 66,047,784 |

| 2026 | 63,772,784 |

| 2027 | 61,497,784 |

| 2028 | 59,222,784 |

| 2029 | 56,947,784 |

| 2030 | 54,672,784 |

The RGGI states also established a Cost Containment Reserve (CCR) of CO2 allowances that creates a fixed additional supply of CO2 allowances that are only available for sale if CO2 allowance prices exceed certain price levels—$13.00 in 2021.[26] In contrast to the CCR, there is an Emissions Containment Reserve (ECR), which serves as the floor and triggers a reduction in allowances if prices drop below the trigger price—$6.00 in 2021.[26] The inclusion of the CCR and ECR ensures emission reduction costs are reasonable.

Compliance

[edit]RGGI compliance obligations apply to fossil-fueled power plants 25MW and larger within the RGGI region. As of 2021, there were 203 such covered sources.[30]

Under RGGI, sources are required to possess CO2 allowances equal to their CO2 emissions over a three-year control period. A CO2 allowance represents a limited authorization to emit one ton of CO2. The first three-year control period took effect on January 1, 2009, and extended through December 31, 2011. The second three-year control period took effect on January 1, 2012, and extended through December 31, 2014. The third three-year control period took effect on January 1, 2015, and extended through December 31, 2017. The fourth three-year control period took effect on January 1, 2018, and extended through December 31, 2020. The fifth three-year control period took effect on January 1, 2021, and extends through December 31, 2023.[10]

As of April 2021, 97.5 percent of regulated power plants had met their compliance obligations for the fourth control period.[30]

Quarterly regional auctions

[edit]

The first pre-compliance auction of RGGI CO2 allowances took place in September 2008. Regional auctions are held on a quarterly basis and are conducted using a sealed-bid, uniform price format.[31] Since 2008, the RGGI states have held 54 auctions generating over $4.7 billion in proceeds. Auction clearing prices have ranged from $1.86 to $13.[32]

Any party can participate in the RGGI CO2 allowance auctions, provided they meet qualification requirements, including provision of financial security. Auction rules limit the number of CO2 allowances that associated entities may purchase in a single auction to 25 percent of the CO2 allowances offered for sale in that auction.[33]

The RGGI auctions are monitored by an independent market monitor, Potomac Economics. Potomac Economics monitors the RGGI allowance market in order to protect and foster competition, as well as to increase the confidence of participants and the public in the allowance market.[34] The independent market monitor has found no evidence of anti-competitive conduct, and no material concerns regarding the auction process, barriers to participation in the auctions, competitiveness of the auction results, or the competitiveness of the secondary market for RGGI CO2 allowances.[35]

Market participants can also obtain CO2 allowances in secondary markets, such as the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), or in over-the-counter transactions.[36] The independent market monitor provides quarterly reports on the secondary market for RGGI allowances.[34]

Investment of auction proceeds

[edit]The RGGI states have discretion over how they invest RGGI auction proceeds. They have reinvested proceeds, generated by RGGI auctions in a wide variety of programs. Programs funded through RGGI investment in energy efficiency, renewable energy, direct bill assistance, and greenhouse gas abatement have benefited more than 3.7 million participating households and 17,800 participating businesses. These investments have saved participants money on their energy bills, created jobs, and reduced pollution. In the period 2008 to 2014, programs funded by RGGI investments avoided the use of 2.4 TWh of electricity, 1.6 TWh (5.3×1012 British thermal units) of fossil fuel, and the release of 1.7×106 short tons (1.5×106 tonnes) of carbon dioxide. Over their lifetime, programs funded by RGGI investments estimate to avoid the use of 20.6 TWh of electricity, 22.3 TWh (76.1×1012 British thermal units) of fossil fuel, and the release of 15.4×106 short tons (1.40×107 tonnes) of carbon dioxide.[37]

Energy efficiency represents a large portion of RGGI investments. Ultimately, all electricity consumers, not only those who make upgrades, benefit from energy efficiency programs. For example, investing in efficiency programs—such as weatherizing houses—reduces the amount of electricity used. The decrease in electricity demand actually reduces the overall price of electricity. That means the costs go down for everyone, not just someone who installed new, efficient windows.[38]

Program review

[edit]The RGGI participating states have committed to comprehensive, periodic program reviews to consider program successes, impacts, and design elements.[39] The RGGI states are currently undergoing a 2021 Program Review, which includes technical analyses and regularly scheduled public stakeholder meetings to solicit input.[39] The 2021 Review is expected to be completed in early 2023.[40]

The 2012 and 2016 RGGI Program Reviews completed in 2013 and 2017 resulted in several updates to the program.[9] The 2012 Review led to a 45 percent reduction in the RGGI cap and the introduction of the CCR.[41] The CCR and the reduced cap took effect in 2014. The 2016 Review established the ECR and an additional 30 percent reduction in the RGGI cap from 2020 to 2030.[29] This review also included modifications to the CCR, offset categories, and the minimum reserve price.[29]

History

[edit]On December 20, 2005, seven governors from Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont signed a memorandum of understanding aimed at developing a cap-and-trade program for power sector CO2 emissions in the northeastern and mid-Atlantic region.[42] The MOU established the initial framework for RGGI.[42]

The following year, in 2006, the same seven states amended the MOU and published the first Model Rule draft to guide individual state-level regulations.[9][43] In 2007, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Rhode Island also signed on to the MOU.[43] On December 31, 2008, the 10 MOU states finalized the first Model Rule, setting individual shares of the regional CO2 cap.[43]

RGGI's first compliance period began on January 1, 2009, and the first Model Rule served as the regulatory framework for each participating state until 2013.[9][43] During this time, New Jersey withdrew from the MOU.[43] Groups such as Acadia Center had reported on lost revenue resulting from New Jersey's departure, and argued for renewed participation.[44] After the election of governor Phil Murphy in 2017, New Jersey began to make preliminary moves to rejoin RGGI.[45] New Jersey reentered the RGGI under an executive order on January 29, 2018.[46] Updated Model Rules were released in 2013 and 2017.[9]

Virginia

[edit]Overview

[edit]After the 2017 election of Governor Ralph Northam in Virginia, the state began to make preliminary moves to join RGGI.[47] However, the move was stopped in 2019 when the Republican-controlled state legislature wrote a provision in the budget bill prohibiting the state from joining RGGI.[48] The move to join RGGI was re-introduced as part of the 2020 General Assembly. With a Democratic majority in both the House of Delegates and the General Assembly, the measure passed and was signed into law.[49] Virginia effectively joined RGGI on January 1, 2021.[50][51]

Withdrawal

[edit]On January 15, 2022, after winning the Virginia 2021 gubernatorial election, on his first day in office Governor Glenn Youngkin signed Executive Order 9 calling for a reevaluation of Virginia's membership in RGGI[52] It has been noted that because Virginia entered the initiative through legislative action, Youngkin may lack the legal authority to withdraw from the initiative without legislative approval.[53] On December 7, 2022, the Virginia Air Pollution Control Board (APCB), voted 4–1 with two abstentions to initiate the repeal of state regulations governing its participation in RGGI.[54] Shortly thereafter, the Joint Commission on Administrative Rules, a legislative oversight commission, voted 5–4 on December 20, 2022, objecting to the APCB's action initiating the withdrawal.[55] The APCB took its final step on June 7, 2023, voting 4–3 to adopt the regulation and sent to the Governor's Office for publication in the Virginia Register.[56][57]

Litigation

[edit]On August 21, 2023, the Southern Environmental Law Center on behalf of the Association of Energy Conservation Professionals, Virginia Interfaith Power and Light, Appalachian Voices, and Faith Alliance for Climate Solutions filed a lawsuit in the Fairfax Circuit Court challenging the APCB's authority to withdraw the state from RGGI.

Governor Youngkin's administration maintains that his office does have the power to remove Virginia from RGGI, and that the regional carbon market program is a "regressive tax" that burdens residents.[58][59] The lawsuit alleges the Commonwealth's constitution was violated by the APCB who "suspended and ignored the execution of law and invaded the General Assembly's legislative power."[58][60] The lawsuit also claims that since joining RGGI carbon dioxide emissions from Virginia power plants in Virginia have decreased by nearly 17%, from about 32.8 million short tons in 2020 to about 27.3 million short tons in 2022.[61] Funds paid by Virginia power plants for their excess emissions, meanwhile, have paid for more than $328 million to help low- and moderate-income Virginians with ways to cut energy use and more than $295 million for flood control, a major issue in low-lying coastal and Chesapeake Bay communities.[61]

Pennsylvania

[edit]Overview

[edit]In October 2019, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf issued Executive Order 2019-17 directing the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to begin working on regulations to bring Pennsylvania into RGGI.

In September 2020, Governor Wolf vetoed a bill (House Bill 2025) that would restrict his administration's ability to take part in RGGI without the input of state lawmakers.[62] Wolf vetoed the bill because he believed that the imminent effects of climate change outweighs other issues. Wolf's decision was also heavily influenced by the economic and environmental benefits seen in other RGGI states.

On July 13, 2021, Pennsylvania's Environmental Quality Board (EQB) voted (15–4) to adopt the rulemaking entitled "CO2 Budget Trading Program", otherwise known as RGGI.[63] The Offices of General Counsel and of the Attorney General approved the rulemaking as to form and legality on July 26, 2021, and November 24, 2021, respectively. Further, the Independent Regulatory Review Commission (IRRC), which evaluates whether proposed rules align with public interest, had approved the rulemaking on September 1, 2021.[64][65]

Pennsylvania formally joined RGGI in April 2022, however, Pennsylvania remains unable to participate in the carbon credit auction due to two "separate but related" lawsuits, regarding the constitutionality of Pennsylvania's involvement in RGGI.[66] Environmental advocates have calculated that Pennsylvania has missed out on a cumulative $1.5 billion in missed revenue.[67] On November 1, 2023, the Commonwealth Court ruled that Pennsylvania's participation in the RGGI cooperative was unconstitutional.[68] On November 21, 2023, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro announced his office would appeal the Commonwealth Court's decision.[69]

Legislation opposing RGGI

[edit]At the start of Pennsylvania's 2021–2022 Legislative Session a number of bills in opposition to RGGI were introduced. Notably, H.B. 637 and its Senate counterpart (S.B. 119) attempted to prohibit DEP from taking actions surrounding carbon pricing programs, including RGGI, without legislative approval.[70][71] Both bills failed to garner enough support and expired at the end of the legislative session.[70][71] A similar bill to the previously vetoed H.B. 2025 was reintroduced in the 2022–2023 Legislative Session and is pending before the House Environmental Resources & Energy Committee.[72]

Following the approval by IRRC on September 1, 2021, under Pennsylvania law, a standing committee of either (or both) the Pennsylvania House of Representatives or Pennsylvania Senate is able to, within 14 days, report for full consideration by the House or Senate a concurrent resolution disapproving the regulation at issue.[73] In this case, the Senate Environmental Resources and Energy Committee reported Senate Concurrent Regulatory Review Resolution 1 (SCRRR1) disapproving the rulemaking on September 14, 2021.[74] Once reported the House of Representatives and the Senate have 10 legislative days or 30 calendar days, whichever is longer, to adopt SCRRR1.[73] The Senate approved SCRRR1 on October 27, 2021, within the 10 legislative day limitation.[75] The House of Representatives, however, did not adopt SCRRR1 until December 15, 2021.[76] Governor Wolf then vetoed the resolution on January 10, 2022.[77] In response, on April 4, 2022, the Senate attempted to override the Governor's veto but failed (32–7),[78] just one vote shy of the constitutional two-thirds requirement.[79][80][81]

Legislation supporting RGGI

[edit]In response to and in tandem with opposing legislation, two companion bills were introduced in the 2021–2022 Legislative Session, detailing the appropriation of RGGI auction proceeds to areas of need. Senate Bill 15 and H.B. 1565 were proposed and had Governor Wolf's support but failed to garner enough support and expired at the end of the session.[82][83][84] No such bills have yet to be introduced in the 2023–2024 Legislative Session.[85]

Litigation

[edit]Ziadeh v. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau

[edit]On February 3, 2022, Patrick J. McDonnell, Secretary of the Department of Environmental Protection and Chairperson of the Environmental Quality Board, filed a lawsuit in the Commonwealth Court against the Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau (LRB), its director, and the director of the Pennsylvania Code and Bulletin.[86] Secretary McDonnell alleged that on November 29, 2021, DEP, acting on behalf of the EQB, submitted to the LRB for final publication in the Pennsylvania Bulletin the "CO2 Budget Trading Program Regulation". The director of the Pennsylvania Code and Bulletin acknowledged the submission of the rulemaking but refused to publish it because the period during which the House of Representatives and Senate had to disapprove the rulemaking had not yet expired. On December 10, 2021, Secretary McDonnell again submitted the rulemaking for publication, however, the Senate and House of Representatives in the intervening time had approved a resolution (SCRRR1) disapproving the rulemaking.

Secretary McDonnell claimed that SCRRR1 was procedurally deficient because LRB's interpretation of the 10 legislative days or 30 calendar days (whichever is longer) in which the House of Representatives and Senate must act to disapprove a regulation is incorrect. McDonnell claimed the timeframe for both chambers to act on a disapproval resolution runs concurrently rather than consecutively. In other words, both the House of Representatives and Senate must act within the 10 legislative days or 30 calendar days (whichever is longer), as opposed to LRB's interpretation that each chamber has 10 legislative days or 30 calendar days to act.

For example, the Senate could vote to approve the resolution on the 25th calendar day and transmit the resolution to the House of Representatives which would then have another 10 legislative days or 30 calendar days (i.e., the clock starts over). Under Secretary McDonnell's interpretation in such a scenario, the House of Representatives would only have 5 days to act on the resolution (the timeframe is concurrent for both chambers).[87]

Injunction granted

[edit]On April 5, 2022, the Commonwealth Court issued an order temporarily blocking publication of the RGGI rulemaking. State legislators, Pennsylvania Senate President Pro Tempore Jake Corman, Senate Majority Leader Kim Ward, Senate Environmental Resources & Energy Committee Chair Gene Yaw, and Senate Appropriations Committee Chair Pat Browne soon after intervened and requested a preliminary injunction barring publication. The stay was deemed dissolved as of April 11, 2022, and the RGGI rulemaking was finally published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin on April 23, 2022.

On July 8, 2022, the Commonwealth Court granted the state Senators' request for a preliminary injunction enjoining DEP from implementing, enforcing, participating, and administrating the RGGI program. The Court found that the Senators had demonstrated irreparable harm per se by raising a substantial legal question as to whether the regulations constituted a tax requiring legislative approval as opposed to a regulatory fee. The Court further found that implementation and enforcement of invalid regulations would cause great harm even if implementation of the regulations would result in "immediate reduction" of carbon dioxide emissions from covered sources. In addition, the Court found that the preliminary injunction would restore the status quo and that the Senators had showed a clear right to relief by raising substantial legal questions about separation of powers issues, as well as whether the allowance auction proceeds were an unconstitutional tax.[88][89][90]

However, the Court found that the Senators did not raise substantial legal questions regarding whether the regulation exceeded authority granted to DEP and EQB to promulgate such a rulemaking, whether the regulations constituted an interstate compact or agreement in violation of the Pennsylvania Constitution, or whether the administrative process through which the regulations were adopted was lawful.[88][91]

Appeal to Pennsylvania Supreme Court

[edit]On July 11, 2022, Acting Secretary Ramez Ziadeh (Secretary McDonnell's service with DEP ended July 1, 2022, and Acting Secretary Ziadeh was substituted as the petitioner)[92] appealed the Commonwealth Courts July 8, 2022, preliminary injunction order to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.[93] In response, the Senators shortly thereafter moved to vacate the automatic stay of the Commonwealth Court's July 8, 2022, order that was triggered by DEP's appealed. The Commonwealth Court granted the motion to vacate the automatic stay and the preliminary injunction remained in effect. On August 31, 2022, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court denied DEP's request to reinstate the stay on the Commonwealth Court's injunction on implementing the RGGI rulemaking.[94][95]

Case dismissed as moot

[edit]On January 19, 2023, the Commonwealth Court dismissed DEP's petition seeking to compel LRB to publish the RGGI rulemaking as moot. The Court noted that it was undisputed that the question of law raised by the petition was moot due to the subsequent publication of the rulemaking on April 23, 2022. The Court further found that no exception to the mootness exception applied. The Court said the case raised "remarkable" legal questions of first impression but that any judgement given would be advisory and have no effect. The Court said counterclaims by the Senators who intervened "remain extant" (i.e., the initial question of concurrent or consecutively timeframe remains unresolved).[96][97]

Appeal to Pennsylvania Supreme Court

[edit]On November 21, 2023, the Pennsylvania Governor's Office announced his administration would appeal the Commonwealth Court's ruling, in a statement saying the Commonwealth Court's decision on RGGI were "limited to questions of executive authority, and our Administration must appeal in order to protect that important authority for this Administration and all future governors."[98] The statement urges the Pennsylvania General Assembly to take action, "Should legislative leaders choose to engage in constructive dialogue, the Governor is confident we can agree on a stronger alternative to RGGI," the statement further said, "If they take their ball and go home, they will be making a choice not to advance commonsense energy policy that protects jobs, the environment, and consumers in Pennsylvania."[99] Should Governor Shapiro's administration win the appeal, it is unclear whether the governor will maintain the Commonwealth's membership in RGGI.[100]

See also

[edit]- Climate Stewardship Bill

- The Climate Registry

- Western Climate Initiative

- Midwestern Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord

- Climate Change Action Plan 2001

- List of climate change initiatives

- Regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act

References

[edit]- ^ "Welcome". www.rggi.org. RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "RGGI Fact Sheet" (PDF). RGGI, Inc.

- ^ Huangpu, Kate (2023-11-01). "PA Commonwealth Court strikes down RGGI". Spotlight PA. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ Huangpu, Kate (2023-11-21). "Gov. Josh Shapiro appeals decisions that struck down key climate program to Pa.'s highest court".

- ^ "North Carolina budget blocks RGGI entry | Argus Media". www.argusmedia.com. 2023-09-25. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ "Program Design". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "RGGI Auctions Fact Sheet" (PDF). RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "Program Design". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ a b c d e "Model Rule and MOU Versions | RGGI, Inc". www.rggi.org. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ a b "Compliance". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "RGGI 101 Fact Sheet" (PDF). rggi.org. September 2021.

- ^ Fairfield, Hannah (June 6, 2014). "Best of Both Worlds? Northeast Cut Emissions and Enjoyed Growth". The New York Times.

- ^ "Obama's Power Plant Rules Can Work". The Baltimore Sun. August 3, 2015.

- ^ "Proof That a Price on Carbon Works". The New York Times. January 19, 2016.

- ^ Ramseur, Jonathan L. (April 2016). "The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: Lessons Learned and Issues for Congress" (PDF).

- ^ Murray, Brian C.; Maniloff, Peter T. (August 2015). "Why Have Greenhouse Emissions in RGGI States Declined? An Econometric Attribution to Economic, Energy Market, and Policy Factors" (PDF). Energy Economics. 51: 581–589. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2015.07.013.

- ^ "The Economic Impacts of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative on Ten Northeast and Mid-Atlantic States" (PDF). Analysis Group. November 2011.

- ^ "The Economic Impacts of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative on Nine Northeast and Mid-Atlantic States" (PDF). Analysis Group. July 2015.

- ^ Banks, Jonathan; Marshall, David (July 2015). "Regulation Works: How science, advocacy and good regulations combined to reduce power plant pollution and public health impacts; with a focus on states in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative". Clean Air Task Force.

- ^ a b c d e f "RGGI". Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- ^ "Clean Power Plan for Existing Power Plants: Regulatory Actions". archive.epa.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- ^ "Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative Status Report Part I: Measuring Success". Acadia Center. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ "CO2 Emissions from Electricity Generation and Imports in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: 2018 Monitoring Report" (PDF). The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. March 11, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Yan, Jingchi (2021-08-01). "The impact of climate policy on fossil fuel consumption: Evidence from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)". Energy Economics. 100: 105333. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105333. ISSN 0140-9883. S2CID 229578796.

- ^ a b "The Economic Impacts of The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative on Nine Northeast and Mid-Atlantic States" (PDF). Analysis Group. April 17, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The RGGI CO2 Cap". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "Investment of RGGI Proceeds Through 2013 (Published April 2015)" (PDF). RGGI. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "NJDEP | Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) | Air Quality, Energy and Sustainability (AQES)". www.nj.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ a b c d "RGGI 2016 Program Review: Principles to Accompany Model Rule Amendments" (PDF). The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. December 19, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "RGGI States Release Fourth Control Period Compliance Report" (PDF). rggi.org. RGGI, Inc. April 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "RGGI Auctions Fact Sheet" (PDF). RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "Auction Results". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "RGGI Auctions Fact Sheet" (PDF). RGGI, Inc.

- ^ a b "Market Monitor Reports". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "Release: Annual Report on the Market for RGGI CO2 Allowances, 2014" (PDF). RGGI, Inc. May 5, 2015.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: RGGI CO2 Allowance Auctions" (PDF). RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "Delaware and the regional greenhouse gas initiative (RGGI)" (PDF). Sierra Club. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Page, Samantha. "The Northeast's Electricity Bills Have Dropped $460 Million Since They Started Paying For Carbon". ThinkProgress.

- ^ a b "Program Review | RGGI, Inc". www.rggi.org. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- ^ "Preliminary Timeline for Third Program Review" (PDF). The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. September 13, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ "RGGI States Propose Lowering Regional CO2 Emissions Cap 45%, Implementing a More Flexible Cost-Control Mechanism" (PDF). RGGI, Inc. February 7, 2013.

- ^ a b "Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: Memorandum of Understanding" (PDF). Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. December 20, 2005. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Program Design Archive". RGGI, Inc.

- ^ "New Jersey and RGGI: Potential Benefits of Renewed Participation" (PDF). Acadia Center. March 2015.

- ^ Skahill, Patrick (November 9, 2017). "With Christie Out, New Jersey Poised To Rejoin New England In Climate Pact". WNPR. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Murphy signs executive order to reenter Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative". NJTV. January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Virginia moving forward with cap-and-trade plan soon after Democratic win". Washington Examiner. 2017-11-09.

- ^ Walton, Robert (May 3, 2019). "Virginia entry to regional GHG initiative blocked as governor declines to veto budget language". Utility Dive. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ Vogelsong, Sarah (April 14, 2020). "Virginia lawmakers agreed to join a regional carbon market. Here's what happens next". The Virginia Mercury. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ Manzagol, O. Nilay (March 23, 2021). "CO2 emissions prices in the Northeast states reached record levels in most recent auction". Energy Information Administration. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Virginia Is Part of Successful Climate Alliance. Now Republicans Want to Abandon It". Time. 2023-07-13. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Commonwealth of Virginia, Office of the Governor, Executive Order 9 (2022): Protecting Ratepayers from the Rising Cost of Living Due to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

- ^ Vozzella, Laura (2021-12-09). "Youngkin says he will take Virginia out of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative to save ratepayers money". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Paullin, Charlie (2022-12-08). "Virginia begins official withdrawal from regional carbon market". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Paullin, Charlie (2022-12-20). "Legislative commission objects to withdrawal from regional carbon market". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Paullin, Charlie (2023-06-07). "Virginia air board approves withdrawal from regional carbon market". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Commonwealth of Virginia, Volume 39: Issue 25, Virginia Register 2813-2838, July 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "Environmental groups sue to block Virginia's RGGI exit". Utility Dive. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Budryk, Zack (2023-08-21). "Conservation groups sue to keep Virginia in Youngkin-opposed climate program". The Hill. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ "Environmental groups sue to keep Virginia in Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative". AP News. 2023-08-21. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ a b Ress, Dave (2023-08-21). "Environmental groups sue over Virginia's withdrawal from greenhouse gas pact". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ "Wolf vetoes bill that would have required lawmakers' input to join regional climate pact". The Center Square. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ "RGGI". Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ "DEP Response to Legislative Reference Bureau Letter Regarding CO2 Budget Trading Program" (PDF). Department of Environmental Protection. December 10, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ "Regulation Search". www.irrc.state.pa.us. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Hall, Peter (2023-05-24). "Pa. Supreme Court hears arguments on order halting greenhouse gas reduction program". Pennsylvania Capital-Star. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Miller, Cassie. "Pa. misses 7th RGGI auction as litigation keeps involvement in limbo". Pennsylvania Capital-Star. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Miller, Cassie (2023-11-01). "Court blocks Pa.'s entrance into multi-state carbon cap-and-trade program". Pennsylvania Capital-Star. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ Sweitzer, Justin (2023-11-21). "Shapiro administration will appeal court decision on RGGI". City & State PA. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ a b "Bill Information - House Bill 637; Regular Session 2021-2022". The official website for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ a b "Bill Information - Senate Bill 119; Regular Session 2021-2022". The official website for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "Bill Information - House Bill 195; Regular Session 2023-2024". The official website for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ a b Act of June 25, 1982, P.L. 633, as amended, 71 P.S. §§745.1-745.14, known as the Regulatory Review Act.

- ^ Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2021-2022 Legislative Session,"Senate Concurrent Regulatory Review Resolution No. 1"

- ^ Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Senate Legislative Journal for October 27, 2021, 205th of the General Assembly, No. 52.

- ^ Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, House Legislative Journal for December 15, 2021, 205th of the General Assembly, No. 65.

- ^ Micek, Kassia (2022-01-11). "Pennsylvania governor vetoes Senate move to block state from joining RGGI". www.spglobal.com. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Senate Legislative Journal for April 4, 2022, 206th of the General Assembly, No. 11.

- ^ "Senate Republican Caucus Response to Gov. Wolf RGGI Veto". Pennsylvania Senate Republicans. 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Parish, Marley. "Attempt to block Pa. from joining multi-state climate initiative fails in Senate". Pennsylvania Capital-Star. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ "Environmental Law Archives". Babst Calland - Attorneys at Law. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ "Bill Information - Senate Bill 15; Regular Session 2021-2022". The official website for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Bill Information - House Bill 1565; Regular Session 2021-2022". The official website for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Gov. Wolf Joins Democrats to Discuss RGGI Benefits for Environment and Economy". Governor Tom Wolf. 2021-06-14. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Bill Text Search Results". The official website for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ Ziadeh v. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, Verified Petition for Review in the Nature of a Compliant for Permanent and Peremptory Mandamus and for Declaratory Judgement, February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Dep't of Envtl. Prot. v. Pa. Legislative Reference Bureau | PAA". paablog.com. 2023-05-22. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ a b Ziadeh v. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, No. 41 M.D. 2022 (Pa. Commw. Ct. July 8, 2022). Request for Preliminary Injunction Granted

- ^ "Judge halts Pa. power plant carbon dioxide rule". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ "RGGI Pennsylvania: Court blocks Pennsylvania's carbon emissions plan". ABC27. 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Miller, Cassie (2022-11-16). "Pa. appeals court hears oral arguments in fight over RGGI". Pennsylvania Capital-Star. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ "Pennsylvania's top environmental regulator to step down". StateImpact Pennsylvania. 2022-05-23. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Ziadeh v. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, No. 41 MD 2022 (Pa. Commw. Ct. July 11, 2022), Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Ziadeh v. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, No. 79 MAP 2022. (Pa. Aug. 31, 2022). Emergency Application to Reinstate the Automatic Supersedeas

- ^ Levy, Marc (2023-05-24). "Pennsylvania high court appears split over plan to force power plants to pay for carbon emissions". 90.5 WESA. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Ziadeh v. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, 41 MD 2022 (Pa. Commw. Ct. Feb 3, 2022).

- ^ McDevitt, Rachel (2023-01-20). "Claim that Pa. climate program was unlawfully delayed is moot, court says". StateImpact Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Huangpu, Kate; Meyer, Katie (2023-11-21). "PA Gov. Shapiro appeals climate program rulings". Spotlight PA. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ McDevitt, Rachel (2023-11-21). "Shapiro to appeal court decision that stopped Pa. from joining climate program". StateImpact Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ Levy, Marc (2023-11-21). "Pennsylvania governor appeals decision blocking plan to make power plants pay for greenhouse gases". AP News. Retrieved 2023-11-22.