Capitol Hill Occupied Protest

Capitol Hill | |

|---|---|

| Capitol Hill Occupied Protest | |

CHOP on June 9, 2020 | |

| Nickname: CHOP or CHAZ | |

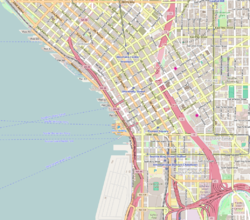

![Area occupied by CHOP[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/26/CapitolHillAutonomousZoneMap10Jun20.jpg/250px-CapitolHillAutonomousZoneMap10Jun20.jpg) Area occupied by CHOP[2] | |

The zone's location, in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood | |

| Coordinates: 47°36′58″N 122°19′08″W / 47.616°N 122.319°W | |

| Designation | Self-declared autonomous zone[1] |

| Established | June 8, 2020[3] |

| Disbanded | July 1, 2020[4] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Consensus decision-making, with daily meeting of protesters[5][6] |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anarchism in the United States |

|---|

|

The Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP),[7][8][9] also known as the Capitol Hill Organized Protest,[10][11][12][13] originally Free Capitol Hill,[14][15] later the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ), was an occupation protest and self-declared autonomous zone[1] in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle, Washington. The zone, originally covering two intersections at the corners of Cal Anderson Park and the roads leading up to them,[16] was established on June 8, 2020, by people protesting the May 2020 killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota.[3] The zone was cleared of occupants by police on July 1, 2020.[4][17]

The formation of the zone was preceded by tense interactions between protesters and police in riot gear which began on June 1, 2020. The situation escalated on June 7 after a man drove his vehicle toward a crowd near 11th Avenue and Pine Street and shot a protester who tried to stop him.[18][19] Tear gas, flash-bangs and pepper spray were used by police in the densely populated residential neighborhood.[20] On June 7, the SPD reported that protesters were throwing rocks, bottles, and fireworks, and were shining green lasers into officers' eyes.[18] The next day, the SPD vacated and boarded up its East Precinct building in an effort to de-escalate the situation.[21] After the SPD had vacated the East Precinct station, protesters moved into the Capitol Hill area. They repositioned street barricades in a one-block radius around the station and declared the area "Free Capitol Hill". The protest area was later renamed the Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP).

The zone was a self-organized space without official leadership.[22] Police were not welcome within the zone. Protesters demanded that Seattle's police budget be decreased by 50%, that funding be shifted to community programs and services in "historically black communities", and that CHOP protesters not be charged with crimes.[22][23][24] Participants created a block-long "Black Lives Matter" mural,[25] provided free film screenings in the street,[26] and performed live music.[27] A "No Cop Co-op" was formed, with food, hand sanitizer and other supplies. Areas were set up for public speakers and to facilitate discourse, and a community vegetable garden was constructed. However the garden was unable to grow any food, so outside food had to be imported. [28]

The CHOP was a focus of national attention during its existence. On June 11, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan stated that the zone had a "block party" atmosphere;[29] later, The New York Times contrasted Durkan's words with local business people's accounts of harassment, vandalism, and looting.[30] The CHOP's size decreased following shootings in or near the zone on June 20, 21, and 23. On June 28, Durkan met with protesters and informed them that the city planned to remove most barricades and limit the area of the zone. In the early morning of June 29, a fourth shooting left a black 16-year-old boy dead and a black 14-year-old boy in critical condition. Calling the situation "dangerous and unacceptable", police chief Carmen Best told reporters: "Enough is enough. We need to be able to get back into the area." On July 1, after Durkan issued an executive order, Seattle police cleared the area of protesters and reclaimed the East Precinct station. Protests continued in Seattle and at the CHOP site over the following days and months.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]

Capitol Hill is a densely populated residential district on a steep hill just east of Seattle's downtown business district, known for its prominent LGBT and counterculture communities and its vibrant nightlife. The Seattle Police Department had been protested against in the past. In 1965, during the civil rights movement after an unarmed black man was shot by an SPD officer, community leaders followed police in "freedom patrols" to observe (and record) their interactions with the Black community.[31][32] Since 2012, the SPD had been under federal oversight after it had been found to use excessive force and biased policing.[33]

Seattle had been the location of other mass protests,[34] such as the 1999 WTO protests[35] and Occupy Seattle.[36] The city is home to several cultural institutions created by occupation protests, including the Northwest African American Museum, the Daybreak Star Cultural Center and El Centro de la Raza.[37][38][39]

Protests over the murder of George Floyd and police brutality began in Seattle on May 29, 2020.[40] Street clashes occurred in greater Seattle for nine days involving protesters, the Seattle Police Department, the Washington State Patrol and the Washington National Guard.[41]

Capitol Hill clashes (June 1–8)

[edit]The zone's formation was preceded by a week of tense interactions in the Capitol Hill neighborhood beginning on June 1, when protesters and police in riot gear began facing off at a police barricade near the SPD's East Precinct building after a child was pepper sprayed and police refused to let paramedics treat the child.[18][42] The SPD used dispersal tactics, including blast balls,[43] flash-bangs and pepper spray.[44] On June 5, Mayor Jenny Durkan and SPD Chief Carmen Best announced a 30-day ban on the use of tear gas.[45][46]

A group of public representatives (including four City Council-members, a King County Council-member, state Senator Joe Nguyen and state Representative Nicole Macri) joined demonstrators on June 6 on the front lines in response to citizen requests, when officers again used flash-bangs and pepper spray to control the crowd.[47]

On June 7, Police installed sturdier barricades around the East Precinct and boarded up its windows.[47][48] The situation intensified after 8 pm, when a demonstrator was shot while trying to slow down a vehicle speeding toward a crowd of 1,000 protesters on 11th Avenue and East Pine Street; the driver left the vehicle with a gun and walked towards the police line, where he was taken into custody without incident.[48] It later became known that the shooter's brother worked at the East Precinct.[19][49] After midnight on June 8, police reported that protesters were throwing bottles, rocks and fireworks. The SPD resumed the use of tear gas (despite the mayor's ban), and used pepper spray and flash-bangs against protesters at 11th and Pine.[18][21] Over 12,000 complaints were filed about police response to the demonstrations, and members of the Seattle City Council questioned how many weapons had been thrown at police.[21]

Police boarded up and vacated the East Precinct during the afternoon of June 8, which Best described as an effort to "de-escalate the situation and rebuild trust".[15][21][3] It remained unclear days later who had decided to retreat from the East Precinct, since Chief Best did not admit responsibility.[50] Durkan later attributed the decision to withdraw to an unnamed SPD on-scene commander.[51] Over a year later, a KUOW report identified Assistant Chief Tom Mahaffey as the one who made the decision, revealing that he had done so without the knowledge of Best or Durkan.[52]

Formation and operation

[edit]On June 8, 2020, after the SPD had vacated the East Precinct station, protesters moved into the Capitol Hill area. They positioned street barricades in a one-block radius around the station, and declared the area "Free Capitol Hill".[15]

Mayor Durkan called the zone an attempt to "de-escalate interactions between protesters and law enforcement",[53] and Best said that her officers would look at approaches to "reduce [their] footprint" in the Capitol Hill neighborhood.[54] City Council member Kshama Sawant spoke to occupants of Cal Anderson Park on June 8[15] and urged protesters to turn the precinct into a community center for restorative justice.[14][55] Police were not welcome within the CHOP.[56][57]

On June 10, about 1,000 protesters marched into Seattle City Hall demanding Durkan's resignation.[58]

Observers described early zone activity on June 11 as a hybrid of other movements, with an atmosphere which was "part protest, part commune";[7] a cross between "a sit-in, a protest and summer festival";[59] or a blend of "Occupy Wall Street and a college cooperative dorm."[26] According to a June 16 Vox article, CHOP had evolved into "a center of peaceful protest, free political speech, co-ops, and community gardens" after protesters recovered from their initial confusion over the police decision to leave the precinct.[11]

On June 11, the SPD announced its desire to reenter the abandoned East Precinct building and said that it still operated in the zone;[60][61] according to Washington governor Jay Inslee, the zone was "un-permitted" but "largely peaceful".[62] The next day, Best said: "Rapes, robberies and all sorts of violent acts have been occurring in the area and we have not been able to get to it."[63] During the early morning of June 12, Isaiah Thomas Willoughby, a former Seattle resident, set a fire at the East Precinct building and walked away; community residents extinguished it before it spread beyond the building's external wall or to nearby tents.[64][65] Later that day, Durkan visited the zone and told a New York Times reporter that she was unaware of any serious crime reported in the area.[66] Most of the people interviewed by Vox had participated in the protests but did not feel safe walking in the area at night, especially in late June. One Capitol Hill resident noted a difference in perspective between outsiders and residents: "I feel a lot of the current 'it's not safe' stuff comes from either people who aren't living in the neighborhood itself or from affluent new arrivals, or from business owners."[32]

Some protesters lived in tents inside the zone.[67] Outside the zone, urban camping was illegal in Seattle[68] but the law was seldom enforced.[69]

On June 13, Black Lives Matter protesters negotiated with local officials about leaving the zone.[70] The CHOP's size decreased four days later (when roadblocks were moved).[71]

On June 15, armed members of the Proud Boys appeared in the zone at a Capitol Hill rally.[10][28] On June 16, an agreement was reached between CHOP representatives and the city to "rezone" the occupied area to allow better street access for businesses and local services.[72] The next day, KING-TV reported that some residents were uneasy with the occupation near their homes: "What you want from a home is a stress-free environment. You want to be able to sleep well, you want to feel comfortable and we just don't feel comfortable right now." The station reported receiving anonymous emails from other residents expressing "real concerns".[73] On June 18, black protesters reportedly expressed unease about the zone and its use of Black Lives Matter slogans. According to NPR, "Black activists say there must be follow-through to make sure their communities remain the priority in a majority-white protest movement whose camp has taken on the feel of a neighborhood block party that's periodically interrupted by chants of 'Black Lives Matter!'"[28]

The CHOP's size continued to shrink after shootings in or near the zone on June 20, 21, and 23.[75][76][77][78] The Star Tribune reported on June 22 that at night, the atmosphere within the zone became charged as demonstrators marched and armed volunteer guards kept watch.[79] On June 22, Durkan and Best said in a press conference that police would reoccupy the East Precinct "peacefully and in the near future";[80][81] no specific timeline was given.[82] CNN quoted "de facto CHOP leader" hip-hop artist Raz Simone two days later as saying that "a lot of people are going to leave; a lot of people already left" the zone.[83] That day, Durkan proposed a police hiring freeze and a $20 million cut to the SPD budget (about a 5% reduction for the rest of 2020) to compensate for a revenue shortfall and unforeseen expenses due to the pandemic. During a public-comment period, community members said that the budget cut should be larger and SPD funds should be redirected to housing and healthcare.[84]

Twelve businesses, residents and property owners filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court against the city, which they said had deprived them of due process by permitting the zone.[85] Saying that they did not want "to undermine CHOP participants' message or present a counter-message", the plaintiffs alleged that their legal rights were "overrun" by the city's "unprecedented decision to abandon and close off an entire city neighborhood" and isolate them from city services.[86] They sought compensation for property damage and lost business and property rights, and restoration of full public access.[85] Community Roots Housing, a public development authority[87] which owns 13 properties near the zone, called for its shutdown on June 30: "These residents have become victims of an occupation better characterized today by its violence, chaos and killings than anything else ... Forcing us to choose between anarchy and police brutality is a false dichotomy. Compassion and law-enforcement should not be mutually exclusive."[88]

On June 28, the mayor met with protesters and informed them that the city planned to remove most barricades and limit the activist area to the East Precinct building and the street in front of it.[89][90][91] That day, CHOP organizers expressed their intention to refocus on the area near the police station and away from the sprawling encampment at Cal Anderson Park after it became a political liability and they struggled to maintain security.[92] In the early morning of June 29, a fourth shooting left a 16-year-old boy dead and a 14-year-old boy in critical condition with gunshot wounds.[93][94][95][96] Calling the situation "dangerous and unacceptable", Best told reporters: "Enough is enough. We need to be able to get back into the area."[97]

Cessation

[edit]At 5:28 a.m. on July 1, Durkan issued an executive order[98] that "gathering in this area [is] an unlawful assembly requiring immediate action from city agencies, including the Police Department."[4] More than one hundred police officers, with help from the FBI, moved into the area and tweeted a warning that anyone remaining or returning would be subject to arrest.[4] Forty-four people were arrested by the end of the day, and another twenty-five were arrested overnight.[4] The SPD posted a YouTube video depicting violent incidents in the Capitol Hill area.[4] Police maintained roadblocks in the area and restricted access to local residents, workers and business owners; some of the latter alleged that the police presence discouraged customers.[99]

Aftermath

[edit]

Street protests continued after the zone was cleared.[101] Protests continued in Seattle and at the CHOP site over the following days and months.[101][102][103] The SPD reported vandalism in the Capitol Hill area during the night of July 19; fireworks were thrown into the East Precinct, starting a small fire which was rapidly extinguished.[104] Donnitta Sinclair Martin, the mother of Lorenzo Anderson, filed a wrongful death claim against the city that the police and fire department had failed to protect or provide medical assistance for her son and city decisions had created a dangerous environment.[105][106]

A group of 150 people returned to the Capitol Hill neighborhood late at night on July 23 and vandalized several businesses, including a shop owned by a relative of a police officer who fatally shot Charleena Lyles, a pregnant black woman, at her home in 2017.[107] On July 25, several thousand protesters gathered in the Capitol Hill neighborhood for demonstrations in solidarity with Portland, Oregon.[108][109] Tensions had escalated in Portland in early July after the Trump administration deployed federal forces against the wishes of local officials, sparking controversy and regenerating the protests.[108][109] The Department of Homeland Security deployed an undisclosed number of federal agents in Seattle on July 23, without notifying local officials, adding to resident unease.[109][110] An initially peaceful march during the early afternoon of July 25 by the Youth Liberation Front was designated a riot by the SPD after several businesses were destroyed, fires were started in five construction trailers near a future juvenile detention center, and the vehicles of several center employees were vandalized.[109][111][112] Forty-seven people were arrested, and twenty-one police officers were injured.[112] According to Crosscut, many protesters had participated in the understanding that the march's central issues (police brutality and federal overreach) were connected.[113]

The New York Times reported on August 7 that weeks after the protests, several blocks remained boarded up and many business owners were afraid to speak out about their experiences.[30] Carmen Best resigned as the chief of police three days later, after the Seattle City Council voted to downsize the department by up to 100 out of its 1,400 officers.[114] On Monday, August 24, following a night of protest against the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin; Alaska resident Desmond David-Pitts helped set a fire against the sally-port door of the East Precinct, while others attempted to bar the door so police could not escape. There was no significant damage, but they soon erected temporary cement barrier walls (which were later replaced by a tall security fence) to prevent further access to the building.[115] Public hearings about the fate of the zone's public art and community garden began in August, and were expected to continue for several months.[116]

On December 16, 2020, an expected third "sweep" of the park was met with resistance by the community. People created makeshift barriers and thwarted SPD's attempts to enter the park.[117] While a federal court considered a temporary restraining order preventing the city from raiding the park, protesters took advantage of the turnout to occupy a private building owned by a real estate developer across the street from the northern end of the park.[118]

Several business owners sued the city in 2020 for damages relating to government conduct during the protests.[119] A federal judge found that the mayor, police chief, and other government officials then illegally deleted tens of thousands of text messages relating to government handling of CHOP. In 2022, the city settled a lawsuit with the Seattle Times for $200,000 over its handling of deleted texts and agreed to improve its record-keeping practices.[120]

Territory

[edit]

The zone was initially centered around the East Precinct building,[121] and barriers were set up on Pine Street for several blocks to stop incoming vehicles.[121] The early territory reportedly encompassed five-and-a-half city blocks, including Cal Anderson Park (already active with demonstrators).[20] It stretched north to East Denny Way, east to 12th Avenue (and part of 13th Avenue), south to East Pike, and west to Broadway.[122] On June 9, one entrance to the zone was marked by a barrier reading "You Are Entering Free Capitol Hill".[15] Other signs read, "You are now leaving the USA" and "Welcome to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone".[16] Signage on the police station was modified as protesters rebranded it the "Seattle People's Department".[123]

On June 16, after city officials agreed with protest organizers about a new footprint,[72] the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) installed concrete barriers wrapped in plywood in several areas along Pine Street and 10th and 12th Avenues[124] (shrinking the area).[71] The revised barrier spacing provided improved access for business deliveries, and the design offered space for decoration by artists affiliated with the protests.[71] The new layout was posted on Durkan's blog: "The City is committed to maintaining space for community to come to together, protest and exercise their first amendment rights. Minor changes to the protest zone will implement safer and sturdier barriers to protect individuals in this area."[72][125]

KIRO-FM reported that on June 17, a large tent encampment was set up on 11th Avenue between Pike and Pine Streets and half of Cal Anderson Park "turned into a huge tent encampment with a massive community garden."[126] The zone's borders were not clearly defined, and shifted daily.[94] Its size was reduced over time, with The Seattle Times reporting that the area had "shrunk considerably" by June 24.[75] Demonstrators redirected their focus to the East Precinct on June 23, when "the Capitol Hill protest zone camp cleared parts of its Cal Anderson Park core."[127]

On June 30, police and other city employees removed a number of concrete barricades and concentrated others closer to the East Precinct.[128] That day, notices were posted announcing a noon closure of Cal Anderson Park for cleaning and repairs; the garden and art created by protesters would be undisturbed.[128] The remaining territory was cleared by Seattle police on July 1,[4][129] and Cal Anderson Park was reportedly closed for repairs.[24]

Culture and amenities

[edit]Services

[edit]

Protesters established the No Cop Co-op on June 9, offering free water, hand sanitizer, kebabs and snacks donated by the community.[14] Stalls offered vegan curry, and others collected donations for the homeless.[59] Organizers pitched tents next to the former precinct to hold the space.[14] Two medical stations were established in the zone to provide basic health care,[123] and the Seattle Department of Transportation provided portable toilets.[14] The city provided waste removal, additional portable toilets and fire and rescue services, and the SPD said that it responded to 911 calls in the zone.[130] The King County public health department provided COVID-19 testing in Cal Anderson Park for a period of time during the protests.[131]

On June 11, The Seattle Times reported that restaurant owners in the area had an uptick in walk-up business and a corresponding reduction in delivery costs.[132] USA Today reported three days later that most businesses in the zone had closed, "although a liquor store, ramen restaurant and taco joint are still doing brisk business."[133] According to The New York Times, "business crashed".[30]

Community gardens

[edit]Vegetable gardens had materialized by June 11 in Cal Anderson Park, where activists attempted to grow a variety of food from seedlings. [134] The gardens were inaugurated with a basil plant introduced by Marcus Henderson, a resident of Seattle's Columbia City neighborhood.[135][134] Activists expanded the gardens, which were segregated by race and self-proclaimed as being "cultivated by and for BIPOC" and included signs heralding black agriculturalists and commemorating victims of police violence.[136] Henderson established his gardening movement as Black Star Farmers, and after the dissipation of the CHOP launched a GoFundMe to continue the work.[137][138] After the park was cleared on July 1, he called supporters of the garden to help him advocate to the city that they allow it to remain as the Black Lives Memorial Garden.[139] The effort succeeded as perhaps the least controversial proposition for how to make use of the public space in Cal Anderson Park after the CHOP's closure. However, in early October 2023, the Seattle Parks & Recreation Department announced their intent to remove the Black Lives Memorial Garden in favor of a "turf renovation" project for the site.[140] The department, backed by SPD, bulldozed the garden at 6am on 27 December 2023.[141][142][143]

Arts and culture

[edit]

The intersection of 12th and Pine was converted into a square for teach-ins (where a microphone was used for organizing) and to encourage those with destructive intentions to leave the area.[14] An area at 11th and Pine was set aside as the "Decolonization Conversation Café", a discussion area with daily topics.[144][145] An outdoor cinema with a sound system and projector was set up on June 9 and screened films, including 13th (a 2016 documentary by Ava DuVernay about racism and mass incarceration) and Paris Is Burning, a 1990 documentary by Jennie Livingston.[14][26]

The Marshall Law Band (a Seattle-based hip-hop fusion group) began performing for protesters during the week of June 1–8 when protesters were confronting police at what was known as "the Western barricade" due to it being one block West of the entrance to the East Precinct.[146] During this week, they played several hour sets with a sign of the protest demands near the stage every single night.[147] The stage was close enough to the barricade that at times when relations between the protesters and cops got violent the band found themselves in the line of fire.[27][147] They kept performing, even when there was tear gas in the air and rubber bullets being fired.[147] The band continued playing regularly once the CHOP was established.[27][6][147] In November 2020, Marshall Law Band released an album called 12th & Pine about their experience as the "House band of the CHOP".[147]

A block-long Black Lives Matter street mural, on East Pine Street between 10th and 11th Avenues, was painted on June 10 and 11.[25] Individual letters of the mural were painted by local artists of color, and supplies were purchased with donations from demonstrators and passersby.[148][37]

Shrines

[edit]Visitors lit candles and left flowers at three shrines with photographs and notes expressing sentiments related to George Floyd and other victims of police brutality.[149][150] Persons for whom shrines, murals, and/or vigils were created:

| Person | Reason for memorializing | Type of memorial | Medium/components | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charleena Lyles | Died from SPD action | Mural | Spray paint and ply wood | [151] |

| George Floyd | Murdered by a Minneapolis police officer | Mural, Shrine | Spray paint and ply wood | [149][150] |

| Lorenzo Anderson | Died in a shooting at the edge of the CHOP | Shrine | Flowers and balloons | [152] |

On June 19, events ranging from a "grief ritual" to a dance party were held to observe Juneteenth.[144][153]

Internal governance

[edit]

Occupants of the zone favored consensus decision-making in the form of general assembly, with daily meetings and discussion groups an alternative to designated leaders.[22][59][5][155]

Protesters held frequent town hall meetings to decide strategy and make plans.[6] Seattle officials said that they saw no evidence of antifa groups organizing in the zone,[62] but some small-business owners blamed antifa for violence and intimidating their patrons.[30] SPD Chief Carmen Best said on June 15, "There is no cop-free zone in the city of Seattle", indicating that officers would go into the zone if there were threats to public safety. "I think that the picture has been painted in many areas that shows the city is under siege," she added. "That is not the case."[156] On August 7, The New York Times described the zone as police abolition in practice, reporting that police generally did not respond to calls in the zone.[30]

Misinformation about its governance circulated.[26] Conservative journalist Andy Ngo shared a video on June 15 of Seattle-based hip hop artist Raz Simone handing a rifle from the trunk of his car to another protester on June 8 (the day the zone was established) after "rumors developed [within the Zone] that members of the right-wing group Proud Boys were going to move into the protest area to set fires and stir chaos."[157] CNN later called Simone the zone's "de facto leader",[83] which he denied.[26] Unbeknownst to the public at the time, Raz was in contact with Seattle Fire Chief Harold Scoggins during his time in CHOP. Simone left the area around July 15.[158]

Names for the area

[edit]| The Uprising (8:46) | |

|---|---|

| Short film on the development of CHOP The Seattle Times, July 4, 2020 | |

The protest area had several names; the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) was most common at the outset, along with "Free Capitol Hill". By its second week, the area was more often referred to as the Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP).[159]

On June 13, a group of several dozen protest leaders agreed to change the name from CHAZ to CHOP.[159] The name change was the result of a consensus to de-emphasize occupation and improve accuracy.[22][160] According to TechCrunch, participants decided to change the name to "the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest—then, noting the fact that Seattle itself is an 'occupation' of native land, change the O to Organized."[161] During the second week of formation, a number of media outlets reported on the name change including The Seattle Times on June 14;[162] KING-TV,[163] KUOW,[160] The Stranger,[164] and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer[13] on June 15; Vox on June 16;[11] and Crosscut on June 17.[55]

Demands

[edit]The number of demands was debated; some believed that the protests were the beginning of a larger revolution, and others said that police brutality should remain the immediate focus.[165] The protesters settled on three main demands:[24][22][23]

- Reducing city police funding by 50%;

- Redistribute funds to community efforts, such as restorative justice and health care; and

- Ensure that protesters would not be criminally liable.

Other demands by the collective included:[166][167][168]

- Reallocation of SPD funds to community health:

- Socialized health and medicine;

- Free public housing;

- Public education;

- Naturalization services for undocumented immigrants; "no person is illegal"; and

- General community development (parks, etc.).

- The release of prisoners serving time for marijuana-related offenses or resisting arrest, and the expungement of their records;

- Mandatory retrials for people of color imprisoned for violent crimes;

- Educational reform, increasing the focus on Black and Native American history;

- Rent control to reverse gentrification; and

- Free college.

One early list (released June 9 in a Medium post attributed to "The Collective Black Voices at Free Capitol Hill") outlined 30 demands, beginning with the abolition of the Seattle Police Department, the armed forces, and prisons.[166][167][168]

On June 10, about 1,000 protesters marched into Seattle City Hall demanding Durkan's resignation.[58]

Security

[edit]

Protesters accepted open carry of firearms as a provision of safety.[26] Members of the self-described anti-fascist, anti-racist and pro-worker Puget Sound John Brown Gun Club (PSJBGC) were reported on June 9 as carrying rifles in the zone[15][169] in response to rumors of an attack by the right-wing Proud Boys.[157] Although the zone was in the restricted area subject to Durkan's May 30 emergency order prohibiting the use of weapons (including guns),[170][171] her ban did not mandate enforcement.[170] The Washington Post reported on June 12 that PSJBGC was on site with no visible weapons,[172] and USA Today reported that day that "no one appeared armed with a gun".[149] Reporters from a Tacoma-based Fox affiliate were chased out of the zone by occupants on June 9.[130]

Area businesses hired private protection services, including Iconic Global, Homeland Patrol Division and Fortress Security, during the occupation. The services deployed men and women (some in uniform and others in plainclothes, armed with AR-15 style rifles and pepper spray) to patrol the zone on foot and in SUVs.[173] Volunteers in the area formed an informal group to provide security, emphasizing de-escalation and preventing vandalism.[174][175]

Outside threats from the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer

[edit]

Since the protest began, protesters were reportedly aware of the threat posed by the far-right groups Patriot Prayer (active in the Pacific Northwest) and the Proud Boys, a national neo-fascist hate group.[157][37] On June 15, armed members of the Proud Boys appeared in the zone at a Capitol Hill rally.[10][28] The group intended to confront what it called protesters' "authoritarian behavior", and video of the clashes went viral.[176]

Proud Boys affiliate and brawler Tusitala "Tiny" Toese was filmed in the zone punching a man and breaking his cellphone on June 15.[10][22][177] Toese has been known in the Pacific Northwest for fighting as a leader of Patriot Prayer[178] and, after early 2019, as a chauvinist member of the Proud Boys.[10][179] He has been called "the right-wing protester most frequently arrested in Portland."[180] A Washington State resident,[177] Toese is the subject of several reports by Portland's Willamette Week.[180][181] Toese was later arrested for violating probation, due to video evidence of assault in the CHOP.[177][178]

Crime

[edit]Shootings

[edit]Before the zone

[edit]On June 7, the day before the zone's founding, a man drove towards a crowd of protesters. He was intercepted by a protester, who reached into his car, grabbing the wheel and punching the driver in an attempt to stop the vehicle, at which point the driver shot him. The driver then stopped and immediately surrendered to the police.[182][48] The victim, wounded in his upper right arm, was expected to fully recover within a year.[48] The driver claimed self-defense; prosecutors said the driver had provoked the incident, and charged him with felony first-degree assault[48][19] but later reduced the charge to misdemeanor reckless driving, "based solely on evidentiary concerns".[183]

During the zone

[edit]During the early morning of June 20, two people were shot in separate operations at the edge of the protest zone.[184][185][186] It was unclear if the shootings were connected to the protests.[185] According to Carmen Best, police officers had wanted to reach the scene more quickly but were prevented by protesters; however, an analysis by KUOW based on 911 transcripts, video recordings, and eyewitness testimony suggested that miscommunication between the SPD and the Seattle Fire Department slowed the emergency response.[187]

Emergency dispatchers received the first reports of gunshots at 10th Avenue and East Pine Street at 2:19 a.m.[185] Seattle Fire Department medics had staged nearby, but did not have permission to enter before police secured the area, and protesters blocked police from approaching the victim.[188] A 19-year-old black man, Horace Lorenzo Anderson Jr., was transported to Harborview Medical Center by volunteer medics. With multiple gunshot wounds, he was pronounced dead at 2:53 a.m.[184][189][190][12] Anderson was a local rapper known as "Lil Mob" and had graduated from high school the previous day.[184][185][191] Anderson was publicly mourned by his teachers and mother in the days following his death.[184] On July 20, Donnitta Sinclair Martin, Anderson Jr.’s mother, filed a wrongful death claim against the City of Seattle.[106] Another man attending the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, Marcel Long, pled guilty to Anderson's murder in 2023.[192]

The second victim, 33-year-old DeJuan Young, was found by a former nurse who determined with the help of a volunteer medic that he had two gunshot wounds.[185][12][186] Young reported that he tried to leave after hearing the first shooting and was surrounded by a group of men, called a racist epithet, and shot at 11th and Pike.[186] Transported to Harborview by 3:06 a.m., he was in critical condition the following day.[12] KIRO-TV reported that Young was shot by different people one block from the site of Anderson's shooting. Young said "I was shot by, I'm not sure if they're Proud Boys or KKK, but the verbiage that they said was hold this 'N——' and shot me." He expressed concern that his case was not being investigated due to the perception that protesters had "asked for the police not to be there, so don't act like y'all need them now,"[186] but Young was outside the zone when he was shot.[193][186]

Armed police eventually entered the zone in riot gear but were informed by protesters that "the victim left the premises".[194] City Council member Lisa Herbold, chair of the public-safety committee, said that the suggestion that the crowd interfered with access to victims "defies belief".[80] Although the SPD reviewed public-source and body-camera video,[195][196] no suspects were arrested and a motive had not been determined.[182][194] CHOP representatives alleged that the individuals involved had a history which apparently escalated because of "gang affiliations".[197]

Another shooting occurred on June 21, the third in the zone in less than 48 hours. After being transported in a private vehicle to Harborview Medical Center, a 17-year-old male was treated for a gunshot wound to the arm and released; he declined to speak to SPD detectives.[198][199]

On June 22, Durkan said the violence was distracting from the message of thousands of peaceful protesters. "We cannot let acts of violence define this movement for change," she said, adding that the city "will not allow for gun violence to continue in the evenings around Capitol Hill." Durkan announced that officials were working with the community to end the zone.[198] "It's time for people to go home," she said, "to restore order and eliminate the violence on Capitol Hill."[200] At the same press conference, Best described "groups of individuals engaging in shootings, a rape, assault, burglary, arson and property destruction ... I cannot stand by, not another second, and watch another black man, or anyone really, die in our streets while people aggressively thwart the efforts of police and other first responders from rescuing them."[201]

A fourth shooting near the zone, on June 23, left a man in his thirties with wounds which were not life-threatening. Although the SPD was reportedly investigating, the victim refused to provide information about the attack or a description of the shooter.[202]

The fifth shooting near the zone occurred in the early morning of June 29. A 16-year-old black boy, Antonio Mays Jr., was killed, and a 14-year-old boy was in critical condition with gunshot wounds.[4][94] Mays was a resident of San Diego, California and reportedly left home for Seattle a week earlier.[203] A video showed a series of twelve or thirteen gunshots at 2:54 a.m., just before a voice warns of "multiple vehicles", "multiple shooters" and a "stolen white Jeep" as protesters scrambled into position.[203] After a five-minute lull, another eighteen gunshots are heard as the "white Jeep" crashes into a barricade or a portable toilet. Some witnesses said they believed that shots were being fired from the vehicle, but no evidence has emerged to support this.[203]

During its investigation, the SPD discovered that the crime scene had been disturbed.[96] Police made no arrests in any of the shootings since June 20.[204] According to a volunteer medic who witnessed the incident, CHOP security forces shot at the SUV driven by the teenagers after it crashed into a concrete barrier.[205]

Other crimes

[edit]At a June 10 news conference, Assistant Police Chief Deanna Nollette said: "We're trying to get a dialogue going so we can figure out a way to resolve this without unduly impacting the citizens and the businesses that are operating in that area." Nollette said that police had received reports of "armed individuals" passing barricades set up by protesters as checkpoints, "intimidat[ing] community members", and police "heard anecdotally" of residents and businesses being asked to pay a fee to operate in the area: "This is the crime of extortion."[60] The following day, Best said that police had not received "any formal reports" of extortion and the Greater Seattle Business Association said that it "found no evidence of this occurring".[132] The New York Times reported in August that during the zone's existence, some small business owners were intimidated by demonstrators with baseball bats, asked to pledge loyalty to the movement and choose between CHOP and the police, put on a list of "cop callers", harassed, or threatened with death by a mob.[30]

On June 15, KIRO-TV reported a break-in and fire at an auto shop near the zone to which the SPD did not respond;[206] police chief Carmen Best later said that officers observed the building from a distance and saw no sign of a disturbance.[156] On June 16, Seattle's KIRO-TV quoted an eight-year tenant of an apartment near the East Precinct: "We are just sitting ducks all day. Now every criminal in the city knows they can come into this area and they can do anything they want as long as it isn't life-threatening, and the police won't come in to do anything about it."[207] Frustrated by blocked streets, criminal behavior and lawlessness, some residents moved out and others installed security cameras. A man who said he "100 percent" supported the protest told KOMO-TV, "I don't even feel safe anymore."[208]

On June 18, a volunteer medic intervened during a sexual assault in a tent in the occupied park area; the alleged perpetrator was arrested.[209] NPR reported that day, "Nobody inside the protest zone thinks a police return would end peacefully. Small teams of armed anti-fascists are also present, self-proclaimed community defense forces who say they're ready to fight if needed but that de-escalation is preferred."[28]

The SPD police blotter page listed FBI-reported law-enforcement incidents in the area: 37 incidents in 2019, and 65 incidents through June 30, 2020.[210] Crime in the area from June 2 to June 30 rose 525 percent over the same period in 2019. In addition to two homicides and two non-fatal shootings, the increase included narcotics use, violent crimes (such as rape, robbery, and assault) and increased gang activity.[211]

Commentary

[edit]On June 9, U.S. Senator Ted Cruz said that the zone was "endangering people's lives".[130] President Trump demanded the following day that Inslee and Durkan "take back" the zone, saying that if they did not do it, he would do it for them.[212] Inslee condemned Trump's involvement in the situation, telling him to "stay out of Washington state's business".[213] On Twitter, Trump criticized Inslee and Durkan and called the protesters "domestic terrorists",[6] and Durkan told the president to "go back to [his] bunker", referring to his evacuation to the Presidential Emergency Operations Center during protests the previous month.[214] Durkan said on June 11 that Trump wanted to construct a narrative about domestic terrorists with a radical agenda to fit his law-and-order initiatives, and that lawfully exercising the First Amendment right to demand more of society was patriotism, not terrorism.[215]

USA Today called the zone a "protest haven",[149] the World Socialist Web Site described the zone as an "anarchistic commune",[216] and The Nation called it "an anti-capitalist vision of community sovereignty without police."[217] Conservative commentator Guy Benson called the occupation of Capitol Hill "communist cosplay".[218] Rosette Royale, writing for Rolling Stone, called the zone "a peaceful realm where people build nearly everything on the fly, as they strive to create a world where the notion that black lives matter shifts from being a slogan to an ever-present reality."[219] Tobias Hoonhout, writing for National Review, contrasted the mainstream media coverage of the zone, which he deemed sympathetic, to the negative coverage of the 2016 Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupation.[220] Gregory J. Wallance, writing for The Hill, called the zone "a cautionary tale for police defunding".[221]

Fox News's website posted photographs purportedly from the zone on June 12, include a man with a military-style rifle from an earlier Seattle protest and smashed windows from other parts of Seattle. The website posted an article about protests in Seattle whose accompanying photo, of a burning city, had been taken in Saint Paul, Minnesota, the previous month.[222] According to The Washington Post, "Fox's coverage contributed to the appearance of armed unrest". The manipulated and misleading photos were removed, with Fox News saying that it "regret[ted] these errors".[223] Monty Python alumnus John Cleese tweeted on June 15, after a Fox News anchorwoman read a Reddit post on-air indicating purported "signs of rebellion" within the zone, that the post was a joke referring to a scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.[224]

Activists in other cities sought to replicate the autonomous zone in their communities; police stopped protesters in Portland, Oregon, and Asheville, North Carolina.[225][226] Governor of Tennessee Bill Lee condemned attempts to create an autonomous area in Nashville on June 12,[227] warning protesters in the state that "autonomous zones and violence will not be tolerated."[228] In Philadelphia, a group established an encampment which was compared to the Seattle occupation; however, the group's focus was on protesting Philadelphia's anti-homelessness laws.[229][230][231] In what CNN called "an apparent reference to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) in Seattle," protesters spray-painted "BHAZ" (Black House Autonomous Zone) on June 22 on the pillars of St. John's Episcopal Church, across the street from Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C.[232] The next day, Trump tweeted: "There will never be an 'Autonomous Zone' in Washington, D.C., as long as I'm your President. If they try they will be met with serious force!" Twitter cited Trump's tweet for violating the company's policy against abusive behavior: "specifically the presence of a threat of harm against an identifiable group."[233]

Politico reported that CHOP "was a recurring theme throughout" debate by the U.S. House Judiciary Committee of the Democratic-sponsored police reform bill, on June 17. Representative Debbie Lesko proposed an amendment to cut off federal police grants to any municipality which permits an autonomous zone. Pramila Jayapal, whose district includes the CHOP, blamed Fox News and "right-wing media pundits" for spreading misinformation. The bill was passed by a majority-Democratic vote.[234]

On July 1, referring to the expulsion of protesters from the zone that day by police, U.S. Attorney General William Barr praised Best "for her courage and leadership in restoring the rule of law in Seattle."[235] White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany said, "I am pleased to inform everyone that Seattle has been liberated ... Anarchy is anti-American, law and order is essential, peace in our streets will be secured."[4] The next day, Trump said: "I'm glad to see, in Seattle, they took care of the problem, because as they know, we were going in to take. We were ready to go in and they knew that too. And they went in and they did what they had to do."[236]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Nadeau, Barbie Latza (June 20, 2020). "Seattle Police Investigate Shooting Inside CHAZ". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Olson, Tyler (June 11, 2020). "Seattle's 'Autonomous Zone' is latest escalation in city's lurch to the left: What to know". Fox News. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Sun, Deedee (June 9, 2020). "Armed protesters protect East Precinct police building after officers leave area". KIRO. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Seattle police clear CHOP protest zone". The Seattle Times. July 1, 2020. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ a b McNichols, Joshua (June 12, 2020). "CHAZ chews on what to do next". KUOW-FM. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Elfrin, Tim (June 11, 2020). "'This is not a game': Trump threatens to 'take back' Seattle as protesters set up 'autonomous zone'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Silva, Daniella; Moschella, Matteo (June 11, 2020). "Seattle protesters set up 'autonomous zone' after police evacuate precinct". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Simon, Dan; Reeve, Elle; Silverman, Hollie (June 15, 2020). "Protesters have occupied part of Seattle's Capitol Hill for a week. Here's what it's like inside". CNN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ "Seattle-area protests: Live updates on Saturday, June 13". The Seattle Times. June 13, 2020. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Weill, Kelly (June 16, 2020). "The Far Right Is Stirring Up Violence at Seattle's Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Burns, Katelyn (June 16, 2020). "Seattle's newly police-free neighborhood, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "'We need help': Neighbors concerned after deadly shooting in Seattle's CHOP zone". King 5. June 20, 2020. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Savransky, Becca (June 15, 2020). "How CHAZ became CHOP: Seattle's police-free zone explained". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

Known as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) at first, but as larger political organizations tried to take credit and control over the area, it was rebranded in order to seem less radical. CHOP, the new acronym, now stands for the Capitol Hill Organized (or Occupied) Protest.

- ^ a b c d e f g Burns, Chase (June 10, 2020). "The Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone Renames, Expands, and Adds Film Programming". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Burns, Chase; Smith, Rich; Keimig, Jasmyne (June 9, 2020). "The Dawn of 'Free Capitol Hill'". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Dwilson, Stephanie Dube (June 10, 2020). "'You're Now Leaving the USA': Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone Declared in Seattle". Heavy. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Seattle Police clearing CHOP area after Durkan issues executive order". KOMO. July 1, 2020. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Gardner, James Ross (June 9, 2020). "A Seattle Activist's Fight to Keep the Focus on Police Abuse". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Moreno, Joel (June 9, 2020). "Driver claiming self-defense in Capitol Hill protest shooting has ties to police". KOMO. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Hu, Jane C. (June 16, 2020). "What's Really Going On at Seattle's So-Called Autonomous Zone?". Slate. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

On June 1, protesters began demonstrating at SPD's Capitol Hill precinct building nightly, and most nights, police used flash-bangs and chemical irritants like pepper spray and tear gas to disperse the crowd around the barriers it erected in the blocks surrounding the precinct— including June 7, just two days after Mayor Jenny Durkan announced a 30-day moratorium on tear gas. Activists turned police's barriers around and declared that the surrounding area—roughly 5½ city blocks, which includes a public park—would be for the people."

- ^ a b c d Jimenez, Esmy; Raftery, Isolde (June 8, 2020). "'They gave us East Precinct.' Seattle Police backs away from the barricade". KUOW. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Gupta, Arun (July 2, 2020). "Seattle's CHOP Went Out With Both a Bang and a Whimper". The Intercept. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Frohne, Lauren; Chin, Corinne; Dompor, Ramon (July 4, 2020). "'The Uprising': Watch how Seattle's protests have evolved". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c Chappell, Bill (July 1, 2020). "Seattle Police Clear Capitol Hill Protest Zone After Mayor Issues Emergency Order". NPR. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Huge Black Lives Matter mural in progress on Capitol Hill street". KIRO 7 News. June 11, 2020. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Read, Bridget (June 11, 2020). "What's Going On in CHAZ, the Seattle Autonomous Zone?". The Cut. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Rietmulder, Michael (June 17, 2020). "Meet CHOP's original house band: Seattle's Marshall Law Band soundtracks a movement". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Allam, Hannah (June 18, 2020). "'Remember Who We're Fighting For': The Uneasy Existence Of Seattle's Protest Camp". NPR. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ McBride, Jessica (June 12, 2020). "Seattle Autonomous Zone Videos: What It's Like Inside the CHAZ". Heavy.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Bowles, Nellie (August 7, 2020). "Abolish the Police? Those Who Survived the Chaos in Seattle Aren't So Sure". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020.

- ^ "The 1965 Freedom Patrols & the Origins of Seattle's Police Accountability Movement - Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project". depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Burns, Katelyn (July 2, 2020). "The violent end of the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ "What the federal consent decree means for Seattle Police Department". king5.com. June 5, 2020. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Banel, Feliks (June 5, 2020). "Long history of racial and economic unrest in Seattle". MyNorthwest. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Burton, Lynsi (November 29, 2014). "WTO riots in Seattle: 15 years ago". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Occupy Seattle protesters clash with police on Capitol Hill". The Seattle Times. November 2, 2011. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c Bush, Evan (June 10, 2020). "Welcome to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, where Seattle protesters gather without police". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Vansynghel, Margo; Kroman, David (June 17, 2020). "The future of Capitol Hill's protest zone may lie in Seattle history". Crosscut. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Martinson, Nicole (July 6, 2020). "CHOP May Not Have Lasted, But These Occupied Spaces Did". Seattle Met. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ "George Floyd protesters take to downtown Seattle streets; 7 arrested". KCPQ. May 29, 2020. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Kamb, Lewis (June 9, 2020). "How ambiguity and a loophole undermined Seattle's ban on tear gas during George Floyd demonstrations". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

Between May 30 and June 4, an average of about 71 WSP troopers assisted Seattle police during demonstrations in the city. … Groups of Washington National Guard soldiers, ranging from 74 soldiers on May 31 to 600 soldiers on June 6 and 7, also have been deployed to Seattle at the request of Seattle's Emergency Operations Center and with the governor's authorization.

- ^ del Pozo, Brandon (June 26, 2020). "Watch This Protest Turn From Peaceful to Violent in 60 Seconds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Jones, Liz; Raftery, Isolde (June 10, 2020). "This 26-year-old 'died three times' after police hit her with a blast ball". KUOW. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Beekman, Daniel; Brownstone, Sydney (June 8, 2020). "Seattle council members vow 'inquest' into police budget; some say mayor should consider resigning". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Kamb, Lewis; Beekman, Daniel (June 5, 2020). "Seattle mayor, police chief agree to ban use of tear gas on protesters amid ongoing demonstrations". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Kroman, David (June 5, 2020). "Seattle issues 30-day ban on tear gas at protests". Crosscut. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Seattle-area protests: Live updates for Sunday, June 7". The Seattle Times. June 7, 2020. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Green, Sara Jean (June 10, 2020). "Prosecutors say man who shot protester on Capitol Hill likely provoked the incident". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Hiruko, Ashley; Brazile, Liz (June 8, 2020). "Gunman at Seattle protest claims he feared for his life. Others paint a different picture". KUOW. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Kroman, David (June 19, 2020). "Confusion, anger in Seattle Police Dept. after East Precinct exit". Crosscut. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Kamb, Lewis (June 24, 2020). "Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan and police Chief Carmen Best: A pairing under stress, put to the test". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Raftery, Isolde (July 9, 2021). "We know who made the call to leave Seattle Police's East Precinct last summer, finally". www.kuow.org. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Mazza, Ed (June 11, 2020). "Politicians Tell Trump To Go Back To The Bunker After His Threat To 'Take Back' Seattle". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Live updates: Protesters establish 'Free Capitol Hill' near East Precinct". MyNorthwest. KIRO-FM. June 9, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Vansynghel, Margo; Kroman, David (June 17, 2020). "The future of Capitol Hill's protest zone may lie in Seattle history". Crosscut. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Kaste, Martin (July 1, 2020). "Seattle Officials Shut Down Police-Free Zone Known As 'CHOP'". NPR.org. Archived from the original on November 15, 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Royale, Rosette (June 19, 2020). "Seattle's Autonomous Zone Is Not What You've Been Told". RollingStone.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Rich; Keimig, Jasmyne (June 10, 2020). "Sawant Marches Through City Hall with Demonstrators Demanding Mayor Durkan's Resignation". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Buncombe, Andrew (June 12, 2020). "Seattle's CHAZ: Inside the occupied vegan paradise – and Trump's 'ugly anarchist' hell". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Andone, Dakin; Rose, Andy (June 11, 2020). "Seattle police want to return to vacated precinct in what protesters call an 'autonomous zone'". CNN. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Clark, Peter A. (June 11, 2020). "Seattle Protestors Are Occupying 6 City Blocks As An 'Autonomous Zone'. Some Fear a Police Crackdown Is Imminent". Time. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Darcy, Oliver (June 11, 2020). "Right-wing media says Antifa militants have seized part of Seattle. Local authorities say otherwise". CNN. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Sabur, Rozina (June 12, 2020). "Trump threatens to retake Seattle from 'domestic terrorists' as police hand district to protesters". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Detectives Need Help Identifying East Precinct Arson Suspect". SPD Blotter. June 12, 2020. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Former Seattle resident pleads guilty to arson at Seattle Police East Precinct". Western District of Washington, The United States Attorney's Office, Department of Justice, United States. June 9, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Live Updates on George Floyd Protests: Judge Is Assigned to Officers' Murder Trial". The New York Times. June 13, 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Read, Richard (June 25, 2020). "Seattle's police-free zone was created in a day. Dismantling it will take much longer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Archived copy (PDF) (Ordinance 106615, Section 13). Seattle City Council. March 21, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (Seattle Municipal Code 18.12.250 Archived May 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine) "It is unlawful to camp in any park except at places set aside and posted for such purposes by the Superintendent." - ^ Greenstone, Scott (September 3, 2018). "Why don't police enforce laws against camping in Seattle parks and streets?". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Carlton, Jim (June 12, 2020). "Seattle Protesters Negotiate Over Leaving 'Autonomous Zone'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Gutman, David (June 16, 2020). "Seattle shrinks CHOP area with street barriers". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Smith, Rich. "City and CHOP Residents Agree on New Footprint". SLOG. The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Sebastian (June 18, 2020). "Frustrated residents near Seattle's 'CHOP' zone want their neighborhood back". KING-TV. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ "CHAZ changes name to CHOP to better reflect the demonstrations' message". KOMO News. July 13, 2020. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Cornwell, Paige (June 24, 2020). "Seattle's CHOP shrinking, but demonstrators remain". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Gutman, David (June 25, 2020). "New Black-led group at CHOP says protesters will decide how long they'll stay". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Del Rosario, Simone (June 25, 2020). "CHOP protesters staying put at Seattle police precinct". KCPQ. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Mutasa, Tammy (June 25, 2020). "Future of 'CHOP' still in the air while neighbors worry about future violence". KOMO-TV. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

The crowds have definitely thinned out in the past 48 hours.

- ^ "Seattle will move to dismantle protest zone, mayor says". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Graham, Nathalie (June 22, 2020). "City of Seattle Exploits Shootings to Crack Down on CHOP". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ Gutman, David; Brodeur, Nicole (June 22, 2020). "Seattle police will return to East Precinct, where CHOP has reigned, Durkan says". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Gutman, David; Brodeur, Nicole (June 22, 2020). "Seattle will phase down CHOP at night, police will return to East Precinct, Durkan says". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Toropin, Konstantin (June 24, 2020). "Leader of Seattle's 'autonomous zone' says many protesters are leaving". CNN. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Savransky, Becca (June 25, 2020). "Durkan proposes 5% budget cut to Seattle police; some protesters, councilmembers say it's not enough". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Johnson, Gene (June 24, 2020). "Businesses sue Seattle over 'occupied' protest zone". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Takahama, Elise (June 24, 2020). "Capitol Hill residents and businesses sue city of Seattle for failing to disband CHOP". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "Our story". Community Roots Housing. 2020. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Clarridge, Christine; Cornwell, Paige (June 30, 2020). "Seattle removes some barriers at CHOP". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Cornwell, Paige; Hellmann, Melissa; Long, Katherine; Clarridge, Christine (June 26, 2020). "Mayor Durkan meets with protesters after city thwarted from removing barricades at CHOP". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Burns, Chase; Smith, Rich (June 26, 2020). "Slog PM: COVID-19 Loves American Ignorance, Seattle School Will Be Named After an LGBTQI+ Hero". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Horne, Deborah (June 28, 2020). "Seattle protest zone remains largely intact". KIRO-TV. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Paul (June 28, 2020). "CHOP organizers try to move protest out of park, focus on precinct". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "1 man killed, another injured in shooting near Seattle's 'CHOP' zone Monday morning". KING-TV. June 29, 2020. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c Brownstone, Sydney; Clarridge, Christine (June 29, 2020). "Shooting at Seattle's CHOP protest site kills one, leaves another in critical condition". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

A 16-year-old boy was killed and a 14-year-old boy was wounded early Monday morning when they were shot at 12th Avenue and Pike Street in the protest area known as CHOP, in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Johnson, Kirk (June 29, 2020). "Another Fatal Shooting in Seattle's 'CHOP' Protest Zone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

Two more people have been shot, one fatally, in the fourth shooting in 10 days within the boundaries of the free-protest zone.

- ^ a b Fieldstadt, Elisha (June 29, 2020). "One dead, 14-year-old injured in shooting near Seattle's Capitol Hill Organized Protest zone". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Another shooting in Seattle's protest zone leaves 1 dead". Associated Press. June 29, 2020. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Public Affairs (July 1, 2020). "Mayor Durkan Issues Emergency Order Regarding Capitol Hill Protest Zone". Seattle Police Department. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Janavel, A. J. (July 2, 2020). "Owners say police presence following CHOP sweep is hurting business". Q13 FOX. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Elassar, Paradise Afshar,Alaa (July 7, 2022). "Officers were justified in the fatal shooting of Charleena Lyles, a pregnant mother of 4, jury finds". CNN. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Seattle protests: 10 more arrested; county prosecutors say they don't plan to charge nonviolent protesters". The Seattle Times. July 3, 2020. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Kamb, Lewis (August 7, 2020). "'I absolutely believed I was going to die:' Protester claims she was denied anti-seizure medication in jail". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Groover, Heidi (September 23, 2020). "Protesters march through Seattle in honor of Breonna Taylor; 13 arrested on Capitol Hill". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Carter, Mike (July 19, 2020). "Police say officers injured, buildings vandalized during downtown Seattle protest". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Mother of CHOP shooting victim files wrongful death claim against Seattle". KOMO-TV. July 20, 2020. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Green, Sara Jean (July 20, 2020). "Mother of 19-year-old fatally shot in CHOP zone files wrongful-death claim against city". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Businesses looted, pair of fires started on Capitol Hill, Seattle police say". The Seattle Times. July 23, 2020. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Police and protesters clash at Seattle march". BBC News. July 26, 2020. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Brownstone, Sydney; Groover, Heidi; Malone, Patrick; Baruchman, Michelle (July 25, 2020). "Youth Liberation Front protest in Seattle recalls familiar police standoffs as federal agents stay out of view". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Gutman, David; Bernton, Hal (July 24, 2020). "Durkan pleads for calm as federal agents poised near Seattle". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Franque (July 26, 2020). "Seattle rioters leave a trail of destruction after looting businesses, setting 'explosive' fires". Q13 FOX. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "47 arrested, 21 officers injured in Seattle protests that turned violent". KIRO. July 26, 2020. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Kroman, David. "Seattle protests intensify, even though federal agents are absent". Crosscut. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Read, Richard (August 11, 2020). "Seattle's first Black police chief quits, saying she's unwilling to sacrifice diversity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ "20-month sentence for arson that charred East Precinct, brought SPD's big wall and security fence". Capitol Hill Seattle Blog. May 24, 2021. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Kelmig, Jasmyne (August 6, 2020). "What Will Happen to CHOP's Art and Garden? Time to wade through the Seattle Process and find out". The Stranger. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Brownstone, Sydney and Carter, Mike (December 16, 2020). "Protesters barricade Cal Anderson Park in Seattle to stop homeless encampment's removal by city". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cal Anderson Community Activists Occupy Vacant Building". December 16, 2020. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Judge slaps sanctions on Seattle for deleting thousands of texts between top officials". The Seattle Times. January 20, 2023. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "City settles Seattle Times lawsuit over Jenny Durkan's missing text messages". The Seattle Times. May 6, 2022. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Janavel, AJ (June 9, 2020). Protesters take over streets outside abandoned SPD East Precinct (News report which aired 7:33am local time). KCPQ (Q13). Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Seattle police clear out protester-occupied zone". BBC News. July 2, 2020. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

(Info via a map of zone included in article)

- ^ a b Morse, Ian (June 12, 2020). "In Seattle, a 'project' toward a cop-free world". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "City of Seattle changes barriers in 'CHOP' protest zone". King 5. June 16, 2020. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Durkan, Jenny (June 16, 2020). "City of Seattle Engages with Capitol Hill Organized Protest to make Safety Changes". Office of the Mayor. City Of Seattle. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ Scott, Hanna (June 20, 2020). "Observations from inside Seattle's CHOP". MyNorthwest.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Capitol Hill protest zone shifts out of Cal Anderson Park with remaining core of campers surrounding East Precinct". CHS Capitol Hill Seattle News. June 24, 2020. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Cornwell, Paige; Clarridge, Christine (June 30, 2020). "Seattle removes some barriers at CHOP; protesters erect makeshift replacement barricade". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Rich (July 1, 2020). "Mayor Orders Cops to Sweep CHOP, Protesters Vow to Keep Marching". The Stranger. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Britschgi, Christian (June 10, 2020). "Seattle Protesters Establish 'Autonomous Zone' Outside Evacuated Police Precinct — Is the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone a brave experiment in self-government or just flash-in-the-pan activism?". Reason. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus daily news updates, June 18: What to know today about COVID-19 in the Seattle area, Washington state and the world". The Seattle Times. June 18, 2020. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Long, Katherine K. (June 11, 2020). "Live: Seattle-area protest updates: No police reports filed about use of weapons to extort Capitol Hill businesses, Best says". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Trevor (June 14, 2020). "In Seattle's Capitol Hill autonomous protest zone, some Black leaders express doubt about white allies". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Weinberger, Hannah (June 15, 2020). "In Seattle's CHAZ, a community garden takes root". Crosscut. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Baume, Matt (June 12, 2020). "Meet the Farmer Behind CHAZ's Vegetable Gardens". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Scruggs, Gregory; Kornfield, Meryl (June 20, 2020). "Police enter Seattle cop-free zone after shooting kills a 19-year-old, critically injures a man". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "Values". Black Star Farmers. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Black Collective Voice forms in Seattle to educate and empower the people". MyNorthwest.com. June 25, 2020. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ Friedman, Lena Friedman (August 6, 2020). "In effort to 'memorialize CHOP' and improve Cal Anderson, community talks gardens, art, and lighting". CHS Capitol Hill Seattle News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Call to save the Black Lives Memorial Garden after city announces Cal Anderson 'turf renovation' plan — UPDATE: two weeks notice". Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "City removes Seattle's Black Lives Matter garden at Cal Anderson Park". The Seattle Times. December 27, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ "Black Lives Memorial Garden demolished at Cal Anderson Park in Seattle". king5.com. December 27, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ Schulkin, Rachel (December 27, 2023). "Statement on the removal of the Cal Anderson garden". Parkways. Retrieved December 27, 2023.