Bad Sobernheim

Bad Sobernheim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 49°47′14″N 07°39′10″E / 49.78722°N 7.65278°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| District | Bad Kreuznach |

| Municipal assoc. | Bad Sobernheim |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2019–24) | Michael Greiner[1] (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 54.06 km2 (20.87 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 620 m (2,030 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 141 m (463 ft) |

| Population (2022-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 6,495 |

| • Density | 120/km2 (310/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 55566 |

| Dialling codes | 06751 |

| Vehicle registration | KH |

| Website | www.bad-sobernheim.de |

Bad Sobernheim is a town in the Bad Kreuznach district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the like-named Verbandsgemeinde, and is also its seat. It is a state-recognized spa town, and is well known for two fossil discovery sites and for the naturopath Emanuel Felke. Bad Sobernheim is also a winegrowing town.

Geography

[edit]Location

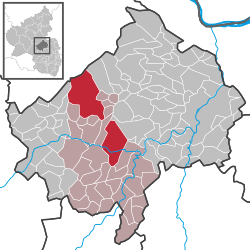

[edit]Bad Sobernheim lies on the middle Nahe about halfway between the district seat of Bad Kreuznach (roughly 20 km southwest of that town) and the gemstone town of Idar-Oberstein. Looming to the north is the Hunsrück, and to the south, the North Palatine Uplands. The municipal area stretches as far as the Soonwald. One notable feature of Bad Sobernheim's municipal area is that it is split geographically into two non-contiguous pieces. The part to the southeast containing the main town holds most of the population, whereas the part to the northwest is only thinly populated, but nevertheless makes up more than half the town's area. This came about as a result of the former Bundeswehr airfield in what is now the northwest part of the town. A great number of the people there chose to move house to Bad Sobernheim to escape the continual noise from aircraft, and the town annexed the land where they had formerly lived, up on the Nahe Heights. Since the residents of Nußbaum did not give their village up, Bad Sobernheim now has a great swathe of land to the northwest of its original municipal area, separated from it by Nußbaum's municipal area.

Neighbouring municipalities

[edit]Clockwise from the north, Bad Sobernheim's neighbours are the municipalities of Waldböckelheim, Oberstreit, Staudernheim, Abtweiler, Lauschied, Meddersheim and Nußbaum. Bad Sobernheim also holds an outlying swathe of territory, not contiguous with the piece containing the actual town – Nußbaum lies between the two areas – and even greater in area, although very thinly populated. Its neighbours, again clockwise from the north, are the municipalities of Sargenroth, Winterbach, Ippenschied, Rehbach, Daubach, Nußbaum, Monzingen, Auen, Langenthal, Seesbach, Weitersborn, Schwarzerden and Mengerschied, the first and last of these both lying in the neighbouring Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis (district).

Constituent communities

[edit]Bad Sobernheim's only outlying Stadtteil is Steinhardt, lying north-northeast of the main centre. Also belonging to Bad Sobernheim, however, are a number of other outlying centres. Some of these lie within the same patch of municipal territory as the main town, namely Dörndich, north-northwest of the main centre, and also Freilichtmuseum, Kurhaus am Maasberg and Neues Leben. Dörndich was once a Bundeswehr facility with barracks that belonged to the Pferdsfeld airfield. Today the area is used by various companies and private citizens. Other centres are also to be found in the municipal exclave lying to the northwest: Eckweiler, Birkenhof, Entenpfuhl mit Martinshof, Forsthaus Alteburg, Forsthaus Ippenschied, Hoxmühle, Kallweiler, Pferdsfeld and Trifthütte.[3] This piece of land was once two former municipalities’ municipal areas. They were the municipalities of Eckweiler and Pferdsfeld.

Climate

[edit]A mild, bracing climate, many sunny days, a long autumn and a mild winter all contribute to the area's being one of Southwest Germany's sunniest regions.[4]

History

[edit]In the New Stone Age (roughly 3000 to 1800 BC) and during the time of the Hunsrück-Eifel Culture (600 to 100 BC), the Bad Sobernheim area was settled, as it likewise was later in Roman times. Beginning about AD 450, the Franks set up a new settlement here. However, only in 1074 was this "villa" (that is, village) of Suberenheim first mentioned in a document, one made out to Ravengiersburg Abbey. The Sobernheim dwellers then were farmers (some of whom were townsmen) and craftsmen, and into modern times they earned their livelihoods mainly at agriculture, forestry and winegrowing. Businesses and trades existed, but they were often linked with farming. Several monastic orders held landholds in the town. Furthermore, several noble families were resident, such as the Counts of Sponheim, the Raugraves and the Knights of Steinkallenfels. Administration was led by an archiepiscopal Schultheiß, who by 1269 at the latest also had three Schöffen (roughly "lay jurists") at his side. They also formed the first town court. In 1259, Sobernheim was split away from Disibodenberg; only the pastoral duties remained in the monks' hands. Sobernheim was from the Early Middle Ages a centre among the estates held by the Archbishopric of Mainz on both the Nahe and the Glan. It was subject to the vice-lord of the Rheingau. The archbishop transferred Saint Matthew's Church (Kirche St. Matthias) to the monks at Disibodenberg. The Romanesque-Early Gothic building was newly built about 1400 and renovated in the 19th century. The town was granted town rights on the Frankfurt model in 1292 by King Adolf of Nassau and again in 1324 by Emperor Louis the Bavarian. It was, however, the town rights on the Bingen model granted by Archbishop Baldwin of Trier in 1330 that became operative and remained so until the French Revolutionary Wars. Until 1259, Sobernheim was administered by Disibodenberg, and thereafter until 1471 by the Burgraves of Böckelheim. In the Nine Years' War (known in Germany as the Pfälzischer Erbfolgekrieg, or War of the Palatine Succession), the fortifications and most of the town's buildings were destroyed by the French. Named in 1403, besides the archiepiscopal Schultheiß, were a mayor and 14 Schöffen drawn from among the townsmen. At that time, there were also Jews living here, who worked at trading. A stone bridge spanned the Nahe beginning sometime between 1423 and 1426, but after a flood shifted the riverbed towards the south in 1627, it sat high and dry in the meadows and was only replaced with the current bridge in 1867–1868. In 1471, Elector Palatine Friedrich I's conquests for Electoral Palatinate included Sobernheim, ending Burgravial rule. Two great fires laid almost the whole town waste in 1567 and 1689. The oldest part of the town hall (Rathaus) was built in 1535, with later expansions being undertaken in 1805, 1837 and 1861–1862. There was already a school sometime after 1530. Despite efforts by the Archbishopric of Mainz, Sobernheim remained with Electoral Palatinate until the French Revolution, then passing to France's Department of Rhin-et-Moselle after the French conquest in the years 1792–1797, which ended the Elector's own rule. Sobernheim became the seat of a mairie ("mayoralty") that included not only the town itself but also the outlying villages of Waldböckelheim, Thalböckelheim, Schloßböckelheim, Steinhardt, Boos, Oberstreit, Bockenau, Burgsponheim and Sponheim as well as a Friedensgericht ("Peace Court"; in 1879 this became an Amtsgericht). After the Napoleonic Wars had ended and the Congress of Vienna had been concluded, the town passed to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1815. The mairie became a Bürgermeisterei (also "mayoralty") under Prussian administration. The year 1817 saw the two Protestant denominations, Lutheran and Reformed, united. In 1857, the King of Prussia once more – for the fourth time in the town's history – granted Sobernheim town rights. In 1858, members of the town's Jewish community built a synagogue. This lasted for 80 years before it was destroyed by Brownshirt thugs on Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938). Industrial development took a long time to make itself felt in Sobernheim, even after the town was linked to the new Rhine-Nahe-Saar Railway in 1859. A cardboard packaging printshop opened for business in 1832, a stocking factory in 1865 and a gelatine factory in 1886/1887. There was also a factory that made sheet-metal articles, and after 1900 there were two brickworks. The Kreuznach district savings bank (Kreissparkasse Kreuznach) was founded in Sobernheim in 1878 and moved to Bad Kreuznach in 1912. A Catholic hospital opened in 1886, as did a location of the Rhenish Deaconry in 1889. In 1888, the Prussian government split the outlying villages from the town, making them a Bürgermeisterei in their own right, called Waldböckelheim. A new development began after 1900 with the introduction of the Felkekur ("Felke cure"). From 1915 until his death in 1926, Pastor Emanuel Felke worked in Bad Sobernheim. He was a representative of naturopathy who developed the treatment so named, which now bears his name. This cure is to this day still applied at Bad Sobernheim's many spa houses. His student Dhonau established a Felke treatment house across the Nahe that began operations in 1907. Further such houses sprang up in 1924 (Stassen), 1926 (Neues Leben) and 1928 (Menschel). The small Amt of Meddersheim was in 1935 brought into joint administration with Sobernheim and, as of 1940, was wholly merged with the town to form the new Amt of Sobernheim. The Second World War brought not only a toll in human lives but also damage from Allied air raids. Reconstruction began with the 1948 currency reform and brought into being a town of some 7,000 inhabitants in which trade, industry, services and public institutions defined economic life. Several central schools, extensive sport facilities and the raising to a Felke spa town are more recent milestones in the town's development. In the course of administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate in 1969 and 1970, the Verbandsgemeinde of Sobernheim was formed. Belonging to this originally were 20 Ortsgemeinden and the town of Sobernheim, but the number of Ortsgemeinden dropped to 18 in 1979 with the dissolution of the Ortsgemeinden of Pferdsfeld and Eckweiler, whose municipal areas made up the swathe of non-contiguous municipal territory lying to the northwest. The German Air Force was stationed at the outlying centre of Pferdsfeld from 1960 with the Leichtes Kampfgeschwader ("Light Combat Squadron") 42 and from 1975 with the Jagdbombergeschwader 35 (Jagdgeschwader 73). On 1 January 1969, a tract of land with 121 inhabitants was transferred from the municipality of Waldböckelheim to Sobernheim. On 10 June 1979, the hitherto self-administering municipalities of Eckweiler and Pferdsfeld were amalgamated with Sobernheim. Since 11 December 1995, the town has borne the designation "Bad" (literally "bath") in recognition of its tradition as a healing centre.[5]

Jewish history

[edit]As early as the Middle Ages, there were Jews living in Sobernheim, with the first mention of them coming from 1301. During the persecution in the time of the Plague in 1348 and 1349, Jews were murdered here, too. In 1357, Archbishop Gerlach of Mainz took two Jews into his protection and allowed them to settle in either Bingen or Sobernheim. Jews were mentioned as being in the town once again in 1384. In the earlier half of the 15th century, there were four or five Jewish families. These families earned their livelihoods at moneylending. In 1418, four Jewish families each paid 10 Rhenish guilders, a woman 4 guilders and three poor Jews 4 guilders in yearly tax to the Mainz stewardship or the Empire. In 1429, all the Jews at Sobernheim (named were Hirtz, Gomprecht, Smohel, Mayer, Smohel's mother and others), together with those throughout the Archbishopric of Mainz, were taken prisoner. It is not believed that this resulted in banishment. Nonetheless, there were clearly no Jews living in Sobernheim in the mid 16th century. The founding of the modern Jewish community came sometime in the 16th or 17th century. Then living in the town were up to five families with all together 20 to 30 persons. After the French Revolution, the community grew from 64 persons in 1808 to a peak of 135 persons in 1895. Beginning in the late 19th century, though, the number of Jews in the town shrank as some either moved away or emigrated. Among Sobernheim's Jews in the 19th and 20th centuries were livestock dealers, butchers, textile sellers, farm product sellers, shoemakers, leather dealers, shop owners and stocking manufacturers. Of particular importance in this last field of business was the Marum stocking factory. In the way of institutions, there were a synagogue (see Synagogue below), a Jewish elementary and religious school with a teacher's dwelling at the house at Marumstraße 20 (this house had been donated after the synagogue's consecration in 1859 by Isaac Werner as a school building), a mikveh (while a supposedly mediaeval one was also unearthed at the house at Großstraße 53 in 1996) and a graveyard (see Jewish graveyard below). To provide for the community's religious needs, an elementary schoolteacher (but later only a religion teacher) was hired, who also busied himself as the hazzan and, although this is not known for sure, as the shochet. Preserved is a whole series of job advertisements for such a position in Sobernheim from such publications as the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums. This one appeared in that newspaper on 1 August 1853:

The local Jewish community seeks for 1 September of this year an efficient elementary teacher and cantor. He must be a native, receives 160 Thaler as salary along with free dwelling and heating. Interested parties please announce themselves as soon as possible, and include a copy of their examination and service records. Sobernheim in Rhenish Prussia. School board J. Werner, J. Klein.

The successful applicant for this job was Alexander Cahn, who then worked in Sobernheim for several decades and was the figure who characterized Sobernheim's Jewish community life in the latter half of the 19th century. He also established a successful Jewish boarding school for boys in the town. Beginning in 1890, schoolteacher Simon Berendt was active in the community. With him, the community celebrated the synagogue's reconsecration in 1904. He celebrated his own 25 years of service in Sobernheim in 1915. In the First World War, four men from Sobernheim's Jewish community fell:

- Rudolf Hesse (b. 26 July 1876 in Sobernheim; d. 24 April 1917)

- Gefreiter Richard Feibelmann (b. 26 November 1889 in Meddersheim; d. 21 November 1917)

- Dr. Joseph Rosenberg (b. 4 April 1886 in Sobernheim, d. of war wounds on 4 May 1922)

- Kurt Metzler

Their names appear on the memorial to the fallen at the Jewish graveyard. In the mid 1920s, Sobernheim's Jewish community still had some 80 persons within a total population of roughly 3,850 (2.1%). Also belonging to the town's Jewish community were the Jews living in Meddersheim (in the mid 1920s, this amounted to 16 persons). The synagogue was then headed by Leopold Loeb, Heinrich Kallmann and Gustav Hesse. In the meantime, Julius Katzenstein had been hired as the cantor and religion teacher. He taught religion at the town's public school to 14 Jewish children. In the way of Jewish clubs, there were a Jewish women's club whose task it was to see to the community's welfare, the club Chewroth whose task it was to see to care of the sick and burials and a Liberal Youth Association. The community belonged to the Koblenz Rabbinate Region. In the early 1930s, the community's leaders were Alfred Marum, Heinrich Kallmann and Mr. Haas. For representation, nine members were part of the leadership, under Richard Wolf's and Moses Fried's chairmanship. The cantor by this time was Felix Moses. In 1933, there were still 83 Jewish inhabitants among the town's population. After 1933, the year when Adolf Hitler and the Nazis seized power, though, some of the Jews moved away or even emigrated in the face of the boycotting of their businesses, the progressive stripping of their rights and repression, all brought about by the Nazis. By Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), only 45 were left. In 1942, the town's last 12 Jewish inhabitants were deported. According to the Gedenkbuch – Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945 ("Memorial Book – Victims of the Persecution of the Jews under National Socialist Tyranny") and Yad Vashem, of all Jews who either were born in Sobernheim or lived there for a long time, 40 were victims of Nazi persecution (birthdates in brackets):

- Rosa Bergheim née Schrimmer (1868)

- Frieda Cohen née Gerson (1887)

- Anna (Anni) Feibelmann née Bergheim (1895)

- Emmy Frankfurter née Metzler (1878)

- Bertha Fried née Kahn (1876)

- Moses Fried (1866)

- Elisabeth Gerothwohl née Herz (1889)

- Ignatz Gerothwohl (1881)

- Klementine Haas née Abraham (1877)

- Anna Hartheimer née Siegel (1880)

- Selma Heimbach née Glaser (1885)

- Benno Heymann (1910)

- Therese Kahn (1869)

- Elise Kallmann née Herz (1873)

- Friedel Katzenstein (1920)

- Markus Klein (1868)

- Johanna Mayer (1880)

- Emilie Landau née Gerson (1882)

- Nathan Landau (1878)

- Clara Lehmann née Wolf (1885)

- Johanna Lichtenstein née Herz (1877)

- Heinrich Marum (1848)

- Johanna Mayer (1880)

- Clementine Mendel (1883)

- Ernst Metzler (1895)

- Gertrud(e) Metzler née Kann (1888)

- Judith Metzger (1933)

- Jakob Ostermann (1872)

- Johanna Ostermann née Mayer (1872)

- Dorothea Pappenheim née Klein (1875)

- Rita J. Rothschild née Wolf (1879)

- Paula Salm née Wolf (1886)

- Melanie Schönwald née Haas (1905)

- Martha Sondermann née Wolf (1892)

- Arthur Wolf (1890)

- Bertha Wolff née Oppenheimer (1856)

- Emilie Wolff (1885)

- Friederike Wolff née Fröhlich (1873)

- Hugo Wolf (1881)

- Otto Wolf (1890)[6]

Criminal history

[edit]Like many places in the region, Bad Sobernheim can claim to have had its dealings with the notorious outlaw Schinderhannes (or Johannes Bückler, to use his true name). The "Steinhardter Hof", an estate in the constituent community of Steinhardt, served him and his sidekick Peter Petri, known as "Schwarzer Peter" ("Black Peter"), as a hideout for a while in the late 18th century.

Religion

[edit]The two big church communities are the Evangelical community of St. Matthias Bad Sobernheim and the Catholic community of St. Matthäus Bad Sobernheim, which belongs to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trier. As at 31 October 2013, there are 6,420 full-time residents in Bad Sobernheim, and of those, 3,176 are Evangelical (49.47%), 1,582 are Catholic (24.642%), 8 belong to the Greek Orthodox Church (0.125%), 2 belong to the Russian Orthodox Church (0.031%), 5 are Lutheran (0.078%), 1 belongs to the Alzey Free Religious Community (0.016%), 2 belong to the North Rhine-Westphalia Jewish community (0.031%), 335 (5.218%) belong to other religious groups and 1,309 (20.389%) either have no religion or did not disclose their religious affiliation.[7]

Politics

[edit]Town council

[edit]The council is made up of 22 council members, who were elected by proportional representation at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.[8]

| SPD | CDU | FDP | Greens | FWG | Total | |

| 2009 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 22 seats |

| 2004 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 22 seats |

Mayor

[edit]Bad Sobernheim's mayor is Michael Greiner (SPD), and his deputies are Alois Bruckmeier (FWG) and Ulrich Schug (Greens).[9]

Coat of arms

[edit]The German blazon reads: Auf Schwarz ein goldener Löwe, rot bekront und bewehrt, rote Zunge, ein silbernes Rad haltend. Auf Silber im Schildfuß ein blaues Wellenband. Die dreitürmige Festungsmauer in grau-braun.

The town's arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: On an escutcheon ensigned with a wall with three towers all embattled grey-brown, sable a lion rampant Or armed, langued and crowned gules between his paws a wheel spoked of six argent, in base argent a fess wavy azure.

As suggested by the blazon, the official version of Bad Sobernheim's coat of arms has a wall on top of the escutcheon, not shown in the version in this article.

The two main charges in the escutcheon are references to the town's former allegiance to two electoral states in the Holy Roman Empire, the Wheel of Mainz for the Electorate of Mainz and the Palatine Lion for Electoral Palatinate. The wavy fess in base symbolizes the Nahe. The "wall crown" in the more up-to-date version recalls the granting of town rights. The arms met with the requirements for the granting of such in 1924.

Town partnerships

[edit]Bad Sobernheim fosters partnerships with the following places:

Culture and sightseeing

[edit]Buildings

[edit]The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[12]

Bad Sobernheim (main centre)

[edit]- Evangelical parish church, Igelsbachstraße 7 – Late Gothic hall church, west tower about 1500 by Peter Ruben, Meisenheim, nave 1482–1484, quire about 1400, converted towards 1500, Romanesque tower; in the churchyard tombs from the 19th century

- Evangelical Philip's Church (Philippskirche) and Kaisersaal ("Emperor’s Hall"), Kreuzstraße 7 – Baroque quarrystone building, 1737–1741, 1901 conversion into inn, 1905 addition of Baroque Revival Kaisersaal, architect Friedrich Otto, Kirn; belonging to the area a building with mansard roof no. 9

- Catholic Maltese Chapel (Malteserkapelle), Malteser Straße 9 – Late Gothic chapel of the former Sovereign Military Order of Malta commandry, about 1426 to about 1465, nave reconstructed in 1671

- Saint Matthew's Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Matthäus), Herrenstraße 18 – Late Gothic Revival hall church, 1898–1900, architect Ludwig Becker, Mainz; on the churchyard wall cast-iron hearth heating plates with reliefs and Baroque figure of Saint John of Nepomuk, 18th century

- Town fortifications – built after 1330, destroyed 1689, reconstructed in altered form; preserved parts of the town wall: between Kirchstraße 9 and 13; near Kapellenstraße 5 (former Disibodenbergerkapelle); behind Poststraße 39 and 41; between Großstraße 91 and Ringstraße 3; behind Ringstraße 35 and 37; behind Ringstraße 59 and 61; near Wilhelmstraße 37; behind Bahnhofstraße 24; behind Bahnhofstraße 2 and 4

- Bahnhofstraße – Felke Monument; standing figure, bronze, marked 1935

- Bahnhofstraße 4 – shophouse; Late Classicist plastered building, open-air stairway with porchtop terrace on columns, mid 19th century, addition crowned with gable about 1910

- Bahnhofstraße 21 – former savings bank building; Late Historicist hewn-stone building, marked 1900

- Bahnstraße 1 – railway station; sandstone-block buildings with one- to two-floor reception building, slated hip roofs, latter half of the 19th century

- Dornbachstraße 20 – former town mill; unified group of dwelling and commercial buildings, partly timber-frame, half-hip roofs with off-centre ventilation zones, one marked 1810; millrace, waterwheel

- Eckweiler Straße, at the graveyard – group of tombs: in the shape of an oak stump, 1868; two others of the same type; Gothicized stele, 1855; two Classicist grave columns, mid 19th century; E. Felke tomb, granite block with bronze image, 1926 (?); Families Liegel and Schmitt tomb, façade, Art Nouveau, about 1910; J. Müller tomb, electrotyped angel, wrought-iron fencing, about 1910; Morian tomb, ancient stele, urns, 1898

- Felkestraße 76–96 – former Kleinmühle ("Little Mill"); 19th and early 20th centuries; no. 76/78: three- to four-floor former factory building, no. 86: mill building, Heimatstil, about 1910/1920, next to it a quarrystone building, 19th century; no. 94, 96: originally possibly tenant farmers’ dwelling belonging to complex; hydraulic engineering facilities

- Großstraße 6 – Late Classicist house, partly timber-frame, mid 19th century

- Großstraße 7 – shophouse; Baroque timber-frame building, partly solid, essentially 18th century

- Großstraße 10 – timber-frame house, partly solid, possibly earlier half of the 19th century

- Großstraße 19 – shophouse; timber-frame building, partly solid, essentially possibly 16th/17th century

- Großstraße 35 – shophouse; Late Baroque timber-frame building, partly solid, marked 1754

- At Großstraße 36 – Baroque wooden relief, 18th century

- Großstraße 37 – estate complex; timber-frame house, partly solid, essentially Baroque, marked 1700, remodelled in the early 19th century, gateway arch marked 1772, side building 18th century

- Großstraße 40 – shophouse, essentially 16th/17th century, stairway tower, gateway arch marked 1720, façade remodelled in Classicist form about 1820/1830

- In Großstraße 53 – former mikveh, after 1850

- Großstraße 55/57 – so-called Russischer Hof ("Russian Estate"); three-floor former noble estate, partly timber-frame, stairway tower, marked 1597

- Großstraße 67 – former Gasthaus Deutsches Haus (inn); long Baroque timber-frame building, partly solid, early 18th century

- Großstraße 88 – former house; Late Baroque building with mansard roof, mid 18th century

- Großstraße 2–52,1–57, Marumstraße 26, Marktplatz 2 (monumental zone) – two- to three-floor shophouses, partly timber-frame, mainly from the 16th to 19th centuries

- Gymnasialstraße 9 – former synagogue; Late Classicist building with hip roof, sandstone-block, marked 1859

- Gymnasialstraße 11 – former Realschule; two-wing Baroque Revival building with mansard roof, 1911/1912, architect Friedrich Otto, Kirn

- Gymnasialstraße 13 – former Teutonic Knights commandry; Late Baroque building with hip roof, marked 1750

- Herrenstraße 16 – Catholic rectory; Baroque plastered building, marked 1748

- At Herrenstraße 24 – Renaissance stairway tower, about 1600

- Igelsbachstraße – warriors’ memorial 1914–1918, soldier, bronze, sandstone steles, 1936, sculptor Emil Cauer the Younger

- Igelsbachstraße 8 – Ehemhof, former noble estate; three-floor part with stairway tower, marked 1589, two-floor Baroque part with gateway, 18th century

- Igelsbachstraße 14 – Evangelical rectory; two-part Baroque building, 18th century, expanded in late 19th century; monumental tablet to Wilhelm Oertel

- Kapellenstraße 5 – former Disibodenberg Chapel (Disibodenberger Kapelle); Late Gothic vaulted building, 1401 and years that followed, 1566 conversion to storehouse, vaulted cellar

- Kirchstraße – warriors’ memorial 1870–1871, column with eagle, after 1871

- Kirchstraße 7 – house, architectural part, essentially 16th century, expanded towards the back, remodelled in Late Classicist in mid 19th century; on the north gable a Renaissance window, 16th century

- Kleine Kirchstraße 2 – Baroque building with mansard roof; gateway arch with armorial stone, marked 1722; with Saarstraße 30 the former Malteserhof (estate); barn with gateway arch, 16th century (?)

- At Marktplatz 2 – Madonna, Baroque, 18th century

- Marktplatz 6 – shophouse; three-floor Late Gothic timber-frame building, partly solid, possibly from the 16th century

- Marktplatz 9 – shophouse; Late Baroque building with hipped mansard roof, mid 18th century

- Marktplatz 11 – town hall; representative Late Gothic Revival hewn-stone building, 1861–1863, architect Peters, Bad Kreuznach; belltower and two Late Classicist additions, 1860s

- Meddersheimer Straße 37 – Baroque Revival villa, marked 1893, expanded on the garden side about 1910/1920

- Meddersheimer Straße 42 – villa; two-and-a-half-floor Late Gründerzeit clinker brick building, Renaissance motifs, marked 1890

- Poststraße 5 – villa; Late Gründerzeit two-and-a-half-floor building with hip roof, Renaissance Revival motifs, sandstone and clinker brick, marked 1894

- Poststraße 7 – villa; Late Gründerzeit clinker brick building, Renaissance motifs, about 1890

- Poststraße 11 – two-and-a-half-floor solid building, partly timber-frame, about 1900

- Poststraße 26 – former municipal electricity works; administration building; villalike Late Gründerzeit clinker brick building, about 1900

- Poststraße 30 – villa; one-floor building with mansard roof, Heimatstil, 1914.

- Poststraße 31 – villa; Heimatstil, about 1910

- Priorhofstraße 16/18 – former Priorhof; Renaissance building with stairway tower, marked 1572, oriel window marked 1609, gateway arch 16th or 17th century, addition with cellar arch and Baroque relief

- Ringstraße 36 – former hospital; three-and-a-half-floor villalike Gothic Revival quarrystone building, marked 1893, commercial building

- Saarstraße 17 – timber-frame house, 16th or 17th century

- Saarstraße 30 – former Malteserhof; Baroque building with hipped mansard roof, gateway arch, portal with skylight marked; joined with Kleine Kirchstraße 2 by a gateway arch

- Staudernheimer Straße – signpost/kilometre stone; sandstone obelisk, 19th century

- Staudernheimer Straße 13 – villa; Baroquified building with hip roof, about 1920; town planning focus

- Steinhardter Straße 1/3 – Gründerzeit pair of semi-detached houses; building with hipped mansard roof with Late Classicist elements, about 1870

- Steinhardter Straße 2 – former Villa Zens; Late Classicist plastered building with knee wall, addition with conservatory; in the garden wall the pedestal of a wayside cross, marked 1753

- Wilhelmstraße 3 – Haus „Zum kleinen Erker“; opulent Renaissance building, marked 1614 and 1622; gabled building belonging thereto, essentially 16th century, remodelled in the 19th century in Late Classicist

- Wilhelmstraße 8 – former Steinkallenfelser Hof and “Hohe Burg” inn: building with half-hip roof, essentially 16th century (marked 1532 and 1596); Late Classicist inn, latter half of the 19th century

- Wilhelmstraße 13 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, 18th century, ground floor marked 1840

- Jewish graveyard, “Aufm Judenkirchhof” ("At the Jews’ Churchyard") (monumental zone) – laid out about 1785, area with 140 gravestones beginning from 1829; memorial from 1950 with warriors’ memorial plaque 1914-1918

- Kurhaus Dhonau south of town (monumental zone) – Heimatstil buildings, 1907 until about 1930: Kurhaus ("spa house"), former commercial building, about 1920; Hermannshof with timber framing and covered walkways, before 1920; teahouse not far from the Nahe; Haus Waldeck, villa 1907 (addition in 1958), Haus Helge, about 1930; Arngard group of houses (mud hall and bathhouse); whole complex of buildings

Eckweiler

[edit]- Evangelical church; formerly Holy Cross (Heilig-Kreuz) – Late Gothic aisleless church, about 1500, expanded 1908, ridge turret 1907

Pferdsfeld

[edit]- Alteburgturm, in the Soonwald – four-floor round tower, quarrystone, 1893

- Alteburg forester's house, in the Soonwald – Gründerzeit estate complex along the road, late 19th century

- North of Landesstraße 230 – New Royal Forest Office of Entenpfuhl (nowadays Soonwald Forest Office), one-floor Heimatstil building, about 1900/1910

- South of Landesstraße 230 – Alte Oberförsterei Entenpfuhl ("Old Entenpfuhl Chief Forest Office"), Baroque timber-frame building, partly solid, half-hip roof, earlier half of the 18th century, 1760-1795 residential seat of the Electoral Palatinate hereditary forester Friedrich Wilhelm Utsch. Utsch was thought to be the subject of "Ein Jäger aus Kurpfalz", a popular folk song.

- South of Landesstraße 230, Entenpfuhl – monument to the "Ranger from Electoral Palatinate"; limestone, 1913, sculptor Fritz Cleve, Munich

Steinhardt

[edit]- Bockenauer Straße 19 – estate complex; building with half-hip roof, timber-frame, plastered, marked 1810, timber-frame barn

- Kreuznacher Straße 19 – estate complex; Classicist house, marked 1835

More about buildings and sites

[edit]Saint Matthias Evangelical Parish Church

[edit]Bishop Willigis consecrated Saint Matthias Church (Pfarrkirche St. Matthias) about 1000. The oldest parts (north tower base) are Romanesque, if not Carolingian; the quire is Early Gothic. The main nave was built in the late 15th century, and the tower in 1500, by Peter Ruben from Meisenheim. Besides sumptuous altar baldachin capitals with representations of angels and colouring from the time of building, the organ built by Johann Michael Stumm in 1739, largely preserved in its original state and restored, and the windows by Georg Meistermann are worth viewing.

Disibodenberg Chapel

[edit]The Late Gothic Disibodenberger Kapelle (chapel) was built to a plan by Heinrich Murer von Beckelnheim for the Cistercians of Disibodenberg Abbey on an estate that lay between the town wall and Großstraße, and which had already been presented to the abbey by Archbishop Willigis of Mainz in 975. The estate, which functioned as a tithe-gathering place for the landholds on the middle Nahe and the Glan, grew into the abbey's most important settlement. The chapel, bearing an imprint of the Frankfurt school, was according to dendrochronological studies, in the area of the quire, roofed about 1455, while the nave got its roof somewhat later, about 1493. Both roof frames, given their age, size, quality and completeness are held to be among the most important witnesses to the carpenter's craft in Rhineland-Palatinate. The means of financing the construction of this 23.25 m-long, 7.65 m-wide building came from an inheritance from Katharina von Homburg, widow of Antilmann von Scharfenstein, called von Grasewege, an Electoral Mainz Amtmann at Schloss Böckelheim, who died on 24 December 1388, and whom Catholics revere as Blessed. After the Reformation was introduced under Wolfgang, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken, the chapel was profaned in 1566 by being converted into a storehouse. A vaulted cellar with a height of about 3.90 m was built in, taking in the space between the base of the foundation and the windowsills and thus leading to the loss of the original ground floor's floor level and pedestal zone. Therefore, the chapel can now no longer be entered through any doorway dating from the time of building. The new "high ground floor" thus created lies at the level of the sills of the Gothic windows. Likewise about 1566, in an attempt to gain more stabling room, a wooden middle floor was built in, which is now important to the building's history for both its age and its shaping in the Renaissance style. Since both the later building jobs – the vaulted cellar and the middle floor – came to be in the course of the chapel's profanation after the Reformation was introduced, they can also be considered witnesses to the local denominational history. The west portal's outer tympanum, which shows, under a mighty ogee, in the style of the Frankfurt School, a calvary with Jesus, Mary Mother of God and John the Apostle as well as two thurible-swinging angels attending, is the only one with carved ornamentation in the Nahe-Glan region that has been preserved from the Middle Ages. The artwork is stylistically akin to the tomb carving in nearby St. Johannisberg (constituent community of Hochstetten-Dhaun) and at the Pfaffen-Schwabenheim collegiate church. The motif of the crockets along the ogee, on the viewer's left turned away and on his right opened towards him, are otherwise only found on the west portal of St. Valentin in Kiedrich in the Rheingau. Brought to light in 1985 during restoration work beneath the tympanum was an atlas in the shape of a male figure, which because of his arm warmers reaching down over his palms is described as the Bauhandwerker – roughly "construction worker". The atlas was, after painstaking analysis, walled up again for conservational reasons. After the chapel had been hidden for 111 years behind a print shop's walls, it came back to public awareness in 2010 with the opening of a retail park on the former print shop's property. The Förderverein Disibodenberger Kapelle Bad Sobernheim e.V. (Förderverein means "promotional association" in German) has since set itself the task of finding a cultural use for the old chapel in keeping with its dignity as a former ecclesiastical building, and of permanently opening it to the broader public. In the spring of 2013, however, plans were put forth to turn the Disibodenberg Chapel into a brewpub.[13]

Maltese Chapel

[edit]The Late Gothic Malteserkapelle arose as a church of a settlement of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta/Knights Hospitaller. The quire was built in 1456 and the nave completed in 1465. The chapel's quire stands taller than the nave. The building's exterior is framed by stepped buttresses and windows with fish-bladder tracery. After the Reformation was introduced, the Knights had to leave Sobernheim. The chapel was used as a commercial building and fell into disrepair. After the reintroduction of the Catholic faith in 1664, the chapel, now renovated from the ground up, served as the Catholic parish church. At the Maltese Commandry in 1821, a Progymnasium was established (the Höhere Stadtschule or "Higher Town School"); the chapel was restored in 1837 and was then used as the school chapel. This school is considered the forerunner to the current Gymnasium. After the new Catholic parish church, Saint Matthew's (St. Matthäus) was built in 1898/1899, directly opposite the chapel, six tombs, the baptismal font made about 1625 and a Sacramental shrine from the 15th century were all transferred to the new parish church. The chapel building was converted into a clubhouse. The last renovation work was undertaken in 1999–2003, and since then the Catholic parish of St. Matthäus has been using the building as its Haus der Begegnung ("Meeting House"). The building is under monumental protection.

Saint Matthew’s Catholic Parish Church

[edit]Saint Matthew's Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Matthäus), a Gothic Revival church built by master church builder Ludwig Becker from 1898 to 1899, was consecrated by Bishop Michael Felix Korum. It is a great, three-naved hall church built out of yellow sandstone. It has a Gothic Revival triptych altar from 1905, a Sacramental shrine from the 15th century and an historic organ from 1901/1902 built by Michael Körfer from Gau-Algesheim. The organ is one of Körfer's few still preserved works. In the sanctuary stands the baptismal font made about 1625 and taken from the Maltese Chapel. The 59 m-tall churchtower looms over the town and can be seen from far beyond. Among the glass windows, those in the sanctuary stand out from those elsewhere in the church with their special images and colouring. The middle window uses mediaeval symbolism to describe the Last Judgment. The left window shows church patron Saint Matthew's calling at the tax office, under which are shown Hildegard of Bingen and Simon Peter. Displayed on the right window is the Maltese Chapel's patron, John the Baptist, and underneath, among others, Saint Disibod. On each side of the chancel are wall surfaces shaped in local forms. To the right, the lower part shows the town with the town hall's façade, the parish churches’ towers (both Catholic and Evangelical) and the town's coat of arms. The populace standing before this is shown in the four ages of life and as representatives of ecclesiastical and secular worlds. The historic Körfer organ was thoroughly restored in 2011–2012. The parish church itself is slated to be renovated inside beginning in January 2014

Marketplace

[edit]Worth seeing, too, is the historic marketplace (Marktplatz) with the town hall (Rathaus) from the 16th century, whence all other historical places, leisure facilities and restaurants in town can be easily reached. The marketplace and the neighbouring streets are also the venue for Bad Sobernheim's yearly traditional Innenstadtfest ("Inner Town Festival"), held on the first weekend in September.

Noble estates

[edit]Bad Sobernheim is home to several former landholds once belonging to noblemen or monasteries in bygone centuries. The Steinhardter Hof temporarily served as a hideout towards the end of the 18th century for the robbers Johann Peter Petri, called "Schwarzer Peter" ("Black Peter") and Johannes Bückler, called "Schinderhannes".[14]

Paul Schneider Monumental Column

[edit]In Pferdsfeld, one of the centres in Bad Sobernheim's northwest exclave, stands the Paul-Schneider-Gedenksäule in memory of the martyr Paul Schneider, who was born here.

Synagogue

[edit]About any mediaeval institutions, nothing is known, but there might have been a prayer room on hand in the earlier half of the 15th century, when there were four or five Jewish families in town. The modern Jewish community, too, began with a prayer room in the 17th or 18th century. Beginning in 1816, this was to be found in a private house (the Werner house at Marumstraße 20). As early as the late 1830s, the building police were threatening to close the roughly 25 m2 room as it had become too small for the swelling Jewish community. First, the community strove to secure a plot on Marumstraße (later the site of the Bottlinger house), but this proved to be too small for a new building. Only in 1858, amid great financial sacrifice, was a synagogue built on what is now called Gymnasialstraße, on a piece of land where once had stood a barn. It was a Late Classicist sandstone-block building with round-arched windows and a pyramid roof. The original building was – in comparison with the one that has been preserved – smaller by one window axis; this area was to be occupied by a schoolhouse. About the synagogue's consecration on 18 June 1858, performed by Chief Rabbi Dr. Auerbach together with the Sobernheim cantor and schoolteacher Alexander Cahn, a newspaper report from the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums survives from 19 June 1858, written by "Master Bricklayer S. Hadra":

Sobernheim, 18 June 1858. On this day, the local Jewish community celebrated the consecration of its newly built House of God. This is, in relation to the not very numerous Jewish population, built very roomily, so that in the case of growth thereof by as many again, there would still not be a lack of room. The building itself is built in a suitable modern style. The community spared no expense furnishing its House of God in the worthiest way. They even enjoyed valuable donations and contributions from non-resident members. The consecration celebrations were conducted with great pomp. Many friends from near and far attended to participate on this festive day. The festive procession moved from the old prayer house to the new synagogue. Forth under the grand baldachin of the Chief Rabbis, Dr. Auerbach from Bonn and the local cantor and schoolteacher, Mr. Cahn, followed by the bearers of the Scroll of Law. Hereupon followed the choir that has been newly instituted here by Sobernheim’s young women and men, the officials who were invited to the festivities and other members of the community. The synagogue at this memorable celebration was adorned with leaves and wreaths of flowers by the teacher. Chief Rabbi Dr. Auerbach gave a deeply gripping sermon characterizing the day’s importance. On Saturday, the Jewish community’s schoolteacher and cantor Mr. Kahn preached on the theme “Build me a House of God and I shall live among you.” S. Hadra, Master Bricklayer.

In 1904, the synagogue was thoroughly renovated and expanded towards the west. About the completion of this work and the synagogue's reconsecration on 11 and 12 November 1904, a magazine report from Der Israelit survives from 24 November 1904:

Sobernheim. 14 November 1904. The 11th and 12th of November were high festive days for the local community, as on these days, the expanded and beautified synagogue was consecrated. To the festivities, many guests from here and elsewhere were invited and they showed up. The consecration service held on Friday afternoon, at which, among others, the mayor, the town executive, the Royal District School Inspector, the principal of the local Realschule and representatives of the schoolboards took part, was opened with the motet “Gesegnet sei, wer da kommt im Namen des Herrn” (“Blessed be He who Cometh in the Lord’s Name”), presented by the synagogue choir. Hereupon, the community’s schoolteacher, Mr. Berendt, read out, in an upliftingly expressive voice, Psalm 110. After the choir then sang Ma Tovu (מה טבו), leadership member Mr. Michel’s eldest daughter presented a prologue in exemplary fashion and handed the community head, Mr. M. Marum, the key to the holy ark. He then gave a speech thanking, in brief but heartfelt words, all those who had contributed to the completion of the building work. Upon this, Mr. Marum opened the holy ark and bestowed upon it its ceremonial function. While the choir sang Vaychi benisa (ויחי בנסע), leadership member Mr. Löb took out one of the Torah scrolls and handed it to Mr. Berendt, who with a festive voice spoke the following: “And this is the teaching that Moses set before the Children of Israel, and in this teaching is the Word that served Israel as a banner on its long wandering through history, around which it gathered, the Word, which was its guiding star in friendly and dreary days: Hear, O Israel, the Everlasting, our God, the Everlasting, is the only one.” After the choir and the community had repeated the last words in Hebrew, the Torah scroll was put into the holy ark amid song from the choir for that occasion. Deeply moving and seriously thought-out was Mr. Berendt’s celebratory sermon that followed about the Word of the prophet Isaiah: “ביתי בית תפלה יקרא לכל העמים” (“My house shall be a house of prayer and a house for all people”). After the consecration hereafter performed by him and the reading of the general invocation, the aaronitic blessing was then conferred in Hebrew and German and the consecrational song was presented by the choir. The celebratory service obviously left all participants with an impression fully matching the dignity of the celebration. After a short break, קבלת שבת took place (onset of Shabbat), at which our splendid House of God shone as surely as it had at midday in glorious electric light. On Saturday morning, the main service was held, whereupon the religious celebration concluded. At four o’clock in the afternoon, a banquet began in the hall at the “high castle”. This event, too, went off in the loveliest way, making the festival into a harmonic whole, honouring its organizers and giving all participants a lasting memory. To the following goes credit for the embellishment of the House of God: Mrs. Jakob Kaufmann née van Geldern, who by collections among the women made possible a magnificent parochet; Mr. Ferdinand Herz, who endowed a sumptuous shulchan cover (for the lectern); Mrs. Else Jakobi née Marum from Grünstadt and Mr. B. Steinherb from Aachen, who each donated a richly ornamented Torah mantle. The Family Jakob Marum from Karlsruhe gave a rare carpet that decorates the inside of the House of God.

In 1929, the synagogue's roof was renovated. In August 1930, a memorial tablet to the fallen from Sobernheim in the First World War was put up at the synagogue. On Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), the synagogue was demolished and desecrated. The prayer books were burnt. Somebody managed to save the Torah scrolls and the parochet. The memorial tablet to the fallen was broken to bits, but Alfred Marum safely gathered up the bits (he put it back together and on 15 October 1950, set it in the memorial at the graveyard, fractured though it still was; the Jewish worship community of the Bad Kreuznach and Birkenfeld districts replaced it with a replica of the original in January 2005). In 1939, the synagogue was sold to the town, who had in mind to turn the building into an atrium for the Gymnasium. In the Second World War, however, the synagogue was used as a storage room by the Wehrmacht. In 1953, after the war, the building was sold to the owner of the Schmidt department store and thereafter used for furniture storage. Intermediate floors were built inside. In 1971, the building was threatened with being torn down. A broad bypass road was, according to the plans then put forth, to lead right across the plot occupied by the synagogue. Only with great effort could the application to put the building under monumental protection be put through. The town and the owner objected, albeit unsuccessfully. In 1986, the building was once again sold, and then used for drink storage and stockpiling. On 9 November 1989 – the 51st anniversary of Kristallnacht – the Förderverein Synagoge Sobernheim e.V. (Sobernheim Synagogue Promotional Association) was founded. It set itself the goal of conserving the legacy of Jewish culture in Bad Sobernheim. Central to its purpose from the outset were the preservation and renovation of the synagogue. The House of God was to be led to a use that was wise and in line with its dignity. The use to which the building was to be led turned out to be as the new home for the town's public library, which would allow the space formerly used for worship to keep its original shape (the intermediate floors were to be torn out). In 2001, the town of Bad Sobernheim acquired the synagogue. Through a usage and maintenance agreement, the building passed into the promotional association's care. In 2002, the roof and the windows were repaired. The Family Marum's descendants donated a new Star of David for the roof. At once, several memorial events, concerts and even Jewish religious services took place inside, even though at first, it did not look very appealing. In connection with this, close contacts were developed between the promotional association, the Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland (Central Welfare Post of the Jews in Germany, represented locally by Max-Willner-Haus in Bad Sobernheim) and the Jewish worship community in Bad Kreuznach. In 2003, the first Jewish religious service in 65 years took place at the synagogue. Between 2005 and 2010, the restoration of the old synagogue was undertaken, and it was turned into the Kulturhaus Synagoge. This was festively dedicated on 30 May 2010. The address in Bad Sobernheim is Gymnasialstraße 9.[15]

Jewish graveyard

[edit]The Jewish graveyard in Bad Sobernheim is believed to have existed since the early 19th century. Its earliest appearance in records was in the original 1825 cadastral survey. Rural cadastral names such as "Auf'm Judenkirchhof" or "In der Judendell", however, may mean that it has existed longer. If the Bad Sobernheim graveyard was only laid out in 1820 or thereabouts, it is unclear where the town's Jewish families would have buried their dead before that, although candidates include the central graveyards in Bad Kreuznach, Gemünden and Meisenheim. Registered as the graveyard's owner in 1826 was the horse dealer Philipp Werner (at the time, the Jewish community could not function as an incorporated body and thus could not own things). The graveyard was still in the Family Werner's ownership in 1860. In 1856, a field beside the Jewish graveyard was named that was in the Jewish community's ownership, which became the new annex to the graveyard (the new Sobernheim and Monzingen section). The oldest preserved gravestone is from 1829, bearing the aforesaid Philipp Werner's name. The last three burials were in the time of the Third Reich, shortly before the deportations began. Those buried were Ida and Hermann Wolf and also Jonas Haas. No further gravestones were ever placed. The graveyard's area is 6 979 m2, making it the second biggest in the Bad Kreuznach district. The graveyard is divided into four parts, the old and new Sobernheim sections, the Waldböckelheim section and the Monzingen section. Standing in the Monzingen section are gravestones from the Monzingen graveyard, which was levelled in 1938. The gravestones were transferred to Bad Sobernheim. In the Waldböckelheim section, members of the Jewish community in Waldböckelheim were buried in the 19th century. There was a relationship between Waldböckelheim and Sobernheim especially in the Family Marum: Anselm Marum the Younger was born in Waldböckelheim, but he later became leader of the Jewish community in Sobernheim. The old Sobernheim section is where the dead from Sobernheim were buried in the 19th century. Beginning in 1902, the new Sobernheim section was used. The first burial there was Sara Marum, who had founded the Marum stocking factory. In the middle, among the sections, stands the 1950 monument where the memorial tablet to the fallen from the First World War is set. This was to be found at the synagogue (see Synagogue above) until 1938, and it was replaced with a replica in 2005. There was another, smaller Jewish graveyard at the northwest edge of the town graveyard "Auf Löhborn", behind the chapel, that was laid out in 1925. This new burying ground was secured through community leader Leopold Loeb's efforts. Buried there were his wife's siblings and in 1930, Loeb himself. In 1937 – in the time of the Third Reich – the dead buried at this graveyard had to be removed and buried once again at the "Domberg" graveyard. Within the municipal graveyard, Jews were now "unwanted". During the time of the Third Reich, the "Domberg" graveyard was heavily defiled and ravaged. The worst destruction happened on Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), wrought by 10 or 15 men, mostly Brownshirt thugs. They threw the gravestones about and shattered stones and inscription tablets. Quite a few pieces of stone were rolled down the hill or thrown over into neighbouring fields. Parts of the graveyard (among them the left side of the Waldböckelheim section) were then or in the time that followed almost utterly removed. After 1945, the stones – wherever possible – were put back up, but this left some of the stones in the older sections no longer standing in their original places. Many bits of rubble could not be identified and therefore could not be placed. On 15 October 1950, the memorial was dedicated, and now remembers not only the local Jews who fell in the First World War but also those Jews from Bad Sobernheim who died. Even after 1945, the graveyard was defiled several times – at least four – the last time in January 1983, when some 40 gravestones were thrown about and heavily damaged. The plaque at the graveyard reads as follows:

Jewish graveyards “Auf dem Domberg” in Sobernheim. In 1343, the first Jewish fellow townsfolk in Sobernheim were mentioned in documents. Their burial places are unknown. Likely their burials took place outside the town wall. In Napoleonic times about 1800, there was a new burial order. Thereafter, no more dead could be buried in residential areas. At about the same time as the graveyard “Auf Löhborn” was laid out, so was the Jewish graveyard “Auf dem Domberg”. The oldest gravestone comes from 1829. The graveyard is made up of three parts. In the oldest part, the dead are buried with their heads towards Jerusalem, thus eastwards. In the middle part of the graveyard, the dead were buried turned towards the synagogue, which can be seen well from the graveyard. Since the former Jewish graveyard at Monzingen was closed at the NSDAP’s instigation, the available stones from Monzingen were “symbolically” set up at the Sobernheim graveyard. Also worthy of mention is the tablet at the graveyard honouring the fallen Jewish soldiers from the First World War 1914-18. Beginning in 1930, Jewish families buried their dead at the town graveyard “Auf Löhborn”. On the NSDAP’s orders in 1933-34, exhumations of the buried Jews were carried out, and they were eventually buried at the Jewish graveyard “Auf dem Domberg”. With regard to the care of graves, Jewish people have different customs to Christians. After setting the gravestone, the rest of the dead should for ever be undisturbed. It is customary to plant ivy or periwinkle on the graves. When visiting a relative’s grave, one lays a stone on the gravestone, or on the anniversary of his death, a grave candle is lit. The graveyard is closed on all Saturdays as well as on all Jewish holidays.

The Jewish graveyard lies on the Domberg (mountain) east of the town centre, not far from the road "Auf dem Kolben".[16]

Museums

[edit]Bad Sobernheim is home to two museums. The Rheinland-Pfälzisches Freilichtmuseum ("Rhineland-Palatinate Open-Air Museum") has translocated buildings, old cattle breeds (Glan Cattle) and old equipment, showing how the people who lived in the countryside in Rhineland-Palatinate, in the Hunsrück and on the Nahe and other rural places lived and worked in bygone centuries. It is of importance well beyond the local region. The local history museum (Heimatmuseum) has pictures, sculptures and notes made by well known Bad Sobernheim artists such as Jakob Melcher, Johann von der Eltz and Rudolf Desch on display. Many magazines, documents and books by the spa founder and pastor Emanuel Felke can be found here. His works are presented on display boards. Also found here is an extensive collection about the region's geological history.

Palaeontology

[edit]Bad Sobernheim is also known as the discovery site for a number of fossils. Named after its main discovery site, a sand quarry in the outlying centre of Steinhardt, are Steinhardter Erbsen, or "Steinhardt Peas", sandstone concretions containing fossils, mostly plants.[17] These ball-shaped sandstones contain plant and animal remnants that are roughly 30,000,000 years old, from the Oligocene. Wrapping the fossils inside one of these "peas" is baryte. The peas presumably formed inside hot springs that apparently were linked with a geological remoulding near Steinhardt and bore barium chloride. When plants and animals decay in an oxidizing environment, hydrogen sulphide forms, which reacts with barium chloride to form baryte. In the process, sand is locked around the fossils. Plant remnants like wood and conifer cones are mostly converted into baryte, and only leaves show up as imprints. In the pit of a former Bad Sobernheim brickworks, superb fossils of plants from Rotliegend times (Permian) some 290,000,000 years ago have been unearthed. The name of one of these species, Sobernheimia, recalls its discovery site. At times, whole phyla of horsetails and sequoias have come to light there. Fossil plants from Sobernheim are presented at the Palaeontological Museum in Nierstein.[18] Moreover, small agate druses are now and then found within the town's limits. Other fossils have been found at a basalt quarry near Langenthal.

Sport and leisure

[edit]

In Bad Sobernheim there are an adventure swimming pool, a 3.5 km-long Barfußpfad ("Barefoot Path") on the riverside flats with adventure stations, among them river crossings, one at a ford and another at a suspension bridge, as well as many cycle paths and hiking trails, tennis, golf and miniature golf facilities. There is also a campground.

Parks

[edit]In the inner town lies the Marumpark, once the family Marum's private garden. This family owned a stocking factory located in Bad Sobernheim from 1865 to 1982, which was later donated to the town. Near the middle stands a memorial stone to Arnold Marum, factory founder Sarah Marum's great-grandson.

Clubs

[edit]The following clubs are active in Bad Sobernheim:[19]

- Freundeskreis Partnerschaft Bad Sobernheim - Louvres — "circle of friends" for Bad Sobernheim-Louvres town partnership

- Förderverein Synagoge e.V. — synagogue promotional association

- Förderverein des katholischen Kindergartens Bad Sobernheim e.V. — kindergarten promotional association

- Förderverein Sowwerummer Rosenmontagszug e.V. — Shrove Monday parade promotional association

- Gemischter Chor "Edelweiß" Steinhardt e.V. — mixed choir

- Kulturforum Bad Sobernheim — culture forum

Economy and infrastructure

[edit]Winegrowing and tourism

[edit]Bad Sobernheim belongs to the Nahe wine region. The winemaking appellation – Großlage – is called Paradiesgarten, while individual Sobernheim wineries – Einzellagen – are Domberg and Marbach.[20] Winegrowing and tourism go hand in hand here. The Weinwanderweg Rhein-Nahe ("Rhine-Nahe Wine Hiking Trail"), the Nahe-Radweg ("Nahe Cycle Way") and the Naheweinstraße ("Nahe Wine Road") all run through the town's municipal area and on through the Verbandsgemeinde. Even today, agriculture still defines part of the region's culture, giving rise to, among other things, a great grape and fruit market in the town each autumn. Many winemakers also have gastronomical enterprises. The traditional grape variety is Riesling.

Established businesses

[edit]Among the more important enterprises in Bad Sobernheim are the following:

- Hay, a manufacturer of automotive technology with roughly 1,300 employees at two plants, in Sobernheim and Bockenau;

- Polymer-Chemie, an independent family business with roughly 300 employees, which serves as a link between resource-based manufacturers and the plastic-processing industry, compounding, refining and modifying polymers;

- Ewald, an enterprise founded in 1886 by Carl Ewald in Sobernheim, which has specialized in making sheet and powder gelatine and gelatine hydrolyzates;

- BAZ Spezialantennen, a manufacturer in antenna technology with focus on ferrite antennae for receiving low frequency, very low frequency, sferics, geophysical sferics and Schumann resonances; the firm was founded in 1994 in Bad Bergzabern with the head office moving to Bad Sobernheim in 2012.

Retailers

[edit]Bad Sobernheim's Innenstadtzentrum ("Inner Town Centre") stands on land once occupied by the Melsbach cardboard packaging factory, and is a big shopping centre with branches of Rewe, NKD and Netto as well as a café and two bakeries. On the town's outskirts are found the companies Real, Lidl and Aldi Süd.

Financial services

[edit]The Sparkasse Rhein-Nahe (savings bank) and the Volksbank Rhein-Nahe-Hunsrück both have branches in the town.

Healthcare and spa facilities

[edit]The therapeutic facilities founded by the Bad Sobernheim citizens Felke and Schroth are an important economic factor for the town. Listed here are some of the town's healthcare facilities:

- Asklepios Katharina-Schroth-Klinik Bad Sobernheim – orthopaedic rehabilitation centre for scoliosis and other spinal deformities and for intensive scoliosis rehabilitation using Katharina Schroth's methods[21]

- Romantikhotel Bollant’s im Park & Felke Therme Kurhaus Dhonau

- Hotel Maasberg Therme

- Menschel Vitalresort (near Meddersheim)

- Seniors’ residences: Seniorenresidenz Felkebad

- Pharmacies: Kur-Apotheke at the marketplace and Felke-Apotheke at Saarplatz

Education

[edit]Bad Sobernheim has a state G8 Gymnasium, the Emanuel-Felke-Gymnasium. Moreover, there is a big school centre (Münchwiesen) that houses a primary school and a coöperative Realschule plus. Both schools at the school centre and the Gymnasium have all-day school. The folk high school rounds out the educational offerings for adults. Bad Sobernheim also has two Evangelical kindergartens, Albert-Schweitzer-Haus and Leinenborn. There are also one municipal kindergarten and a Catholic one belonging to the Catholic parish of St. Matthäus.

Libraries

[edit]At the renovated former synagogue, there has been since April 2010 the public municipal library, the Kulturhaus Synagoge. The two former libraries, the Evangelical parish library and the old municipal library, were then brought together at the old synagogue to form a new municipal library.

Media

[edit]- Amtsblatt – public journal

- Allgemeine Zeitung (AZ) – newspaper

- Öffentlicher Anzeiger – flyer

- Wochenspiegel – "Weekly Mirror"

Transport

[edit]Running by Bad Sobernheim is Bundesstraße 41. Serving the town is a railway station on the Nahe Valley Railway (Bingen–Saarbrücken). The bus route BusRegioLinie 260 Bad Sobernheim – Meisenheim – Lauterecken with a connection on to Altenglan runs hourly (every two hours in the evening and on weekends). The town lies within the area of the Rhein-Nahe-Nahverkehrsverbund (RNN; Rhine-Nahe Local Transport Association). Frankfurt-Hahn Airport lies some 30 km away from Bad Sobernheim as the crow flies.

Famous people

[edit]Sons and daughters of the town

[edit]- August Wiltberger (1850–1928), composer and seminary professor of Post-romanticism, honorary citizen of the town

- Bruno Ernst Buchrucker (1878–1966), officer

- Paul Robert Schneider (1897–1939), clergyman, member of the Confessing Church and victim of National Socialism, died at Buchenwald

- Wilhelm Breuning (b. 1920), theologian and dogmatist

- Wolfgang K. Giloi (1930–2009), computer scientist

- Gerhard Engbarth (b. 1950), German storyteller, cabaret artist and musician, lives in Bad Sobernheim

- Harro Bode (b. 1951), sailor

- Elke Kiltz (b. 1952), politician

- Heinz-Peter Schmiedebach (b. 1952), medical historian

- Michael Klostermann (b. 1962), musician

- Michaela Christ (b. 1966), singer

- Guido Henn (b. 1970), musician

- Udo Schneberger (b. 1964), pianist, organist and today music professor in Japan

Famous people associated with the town

[edit]- Friedrich Wilhelm Utsch (1732–1795), hereditary forester to the Elector of Mainz, lived for a long time in Bad Sobernheim

- Philipp Friedrich Wilhelm Oertel (1798–1867), writer, from 1835 Evangelical pastor and superintendent in Bad Sobernheim

- Leopold Erdmann Emanuel Felke (1856–1926), pastor, representative of naturopathy (developed the Felke cure), active in Bad Sobernheim from 1915 to 1925 and also buried here, honorary citizen of the town

- Katharina Schroth (1894–1985), physiotherapist; found in Bad Sobernheim is the Asklepios Katharina-Schroth-Klinik founded by her in 1961

- Rudolf Desch (1911–1997), composer and professor, lived in Bad Sobernheim

- Karl-Heinz Gottmann (1919-2007), medic and superior in a Buddhist order, lived and worked in Bad Sobernheim

- Werner Vogt (1924–2006), "local scientist" and historian, lived in Bad Sobernheim

- Wolfgang Stribrny (1935–2011), German historian, lived from 1997 until his death in Bad Sobernheim, received the town's "Golden Heart"

- Mary Roos (b. 1949) (hit singer, actress) and Tina York (b. 1954) (hit singer), the sisters lived as children for a while in Bad Sobernheim

- Giovanni Zarrella (b. 1978) (musician, moderator) and Jana Ina (b. 1976) (moderator, model), married on 3 September 2005 at Saint Matthew's Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Matthäus)

- Miriam Dräger (b. 1980), football referee, lives in Bad Sobernheim

Further reading

[edit]- Werner Vogt: Bad Sobernheim. Schnell und Steiner, Regensburg 1999, ISBN 3-7954-6191-X

References

[edit]- ^ Direktwahlen 2019, Landkreis Bad Kreuznach, Landeswahlleiter Rheinland-Pfalz, accessed 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerungsstand 2022, Kreise, Gemeinden, Verbandsgemeinden" (PDF) (in German). Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz. 2023.

- ^ Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz – Amtliches Verzeichnis der Gemeinden und Gemeindeteile Archived 2015-11-25 at the Wayback Machine, Seite 17 (PDF)

- ^ Climate

- ^ Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz – Amtliches Gemeindeverzeichnis 2006 Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Seite 170, 205 (PDF; 2,6 MB)

- ^ Jewish history

- ^ Religion

- ^ Der Landeswahlleiter Rheinland-Pfalz: Kommunalwahl 2009, Stadt- und Gemeinderatswahlen

- ^ Bad Sobernheim’s council

- ^ "Louvres". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Edelény Archived 2013-10-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Bad Kreuznach district

- ^ Disibodenberg Chapel brewpub plans

- ^ Peter Bayerlein: Schinderhannes-Ortslexikon, S. 232

- ^ Synagogue

- ^ Jewish graveyard

- ^ Mineralienatlas - Steinhardt (Zugriff Juni 2014)

- ^ Palaeontology

- ^ Clubs

- ^ Weinlagen bei vino.la Archived 2014-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Asklepios Katharina-Schroth-Klinik, Bad Sobernheim

External links

[edit]- Town’s official webpage (in German)

- Verbandsgemeinde’s official webpage (in German)

- "Rhineland-Palatinate Open-Air Museum" (Sobernheim) (in German)

- Information about Sobernheim’s Jewish history – history and photographs of the former synagogue (in German)

- Barfußpfad Bad Sobernheim ("Barefoot Path") (in German)

- Local historical collection of pictures, postcards etc. from Bad Sobernheim