Ashokan Edicts in Delhi

| Ashokan Edicts | |

|---|---|

Askhokan Pillar in Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Edicts on sandstone pillars and on in-situ rocks |

| Town or city | Delhi |

| Country | India |

| Coordinates | 28°37′N 77°14′E / 28.61°N 77.23°E |

| Construction started | 3rd century BC |

| Completed | 3rd century BC |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Ashoka |

The Ashokan edicts in Delhi are a series of edicts on the teachings of Buddha created by Ashoka, the Mauryan Emperor who ruled in the Indian subcontinent during the 3rd century BC. The Edicts of Ashoka were either carved on in-situ rocks or engraved on pillars erected throughout the empire; examples of both are found in Delhi.

The first in-situ rock edict was discovered in Delhi in 1966, and establishes the city's ancient historical link with the Ashokan era (273–236 BC).[1][2][3] Delhi's stone pillar edicts were transported from their original sites in Meerut and Ambala during the reign of Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1351–1388 AD). They were erected in Feruzabad, the fifth medieval city of Delhi, established by Feroz Shah Tughlaq.[2][4][5]

The inscriptions are written in Prakrit, a colloquial language used in everyday speech. The edicts were intended to teach the people of the morals and ideals of civilised living, to bring peace and harmony to the vast empire. The philosophy bears a striking resemblance to the teachings of the Buddha, which his followers believe lead to enlightenment (the universal law of nature), and the constituent elements of the world as it is experienced (the characteristic of elements).[6][2][7]

History

[edit]Until the 3rd century BC, a large region of the Indian subcontinent was ruled by Chandragupta Maurya (322–298 BC), founder of Mauryan Empire. He was the grandfather of Ashoka. Ashoka's father Bindusara ruled from 297 to 272 BC. Ashoka, known as Ashoka the Great, after he took over reigns of the Mauryan Empire from his father then expanded and consolidated his grandfather's region into a much larger empire with command over large swathes of the Indian subcontinent and with his capital at Pataliputra, the present day Patna in Bihar.[8] Ashoka ruled for three decades. During his reign, he underwent a dramatic change in his life-style after winning the Kalinga War of 261 BC, at the cost of immense loss of life. As one of his edict inscriptions states: "150,000 people were forcibly abducted from their homes, 100,000 were killed in battle, and many more died later on".[9] This event had a profound impact upon him. He was repentant. He then decided to renounce further warfare. He then converted to Buddhist religion, as the ethos of Buddhism (teachings of Buddha, an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth} appealed to him. His 13th edict is a form of self indictment: "Even a hundredth or a thousandth part only of the people who were slain, or killed or abducted in Kalinga is now considered as a grievous loss by Devanmpiya, beloved of the Gods, i.e., Ashoka".[9]

He avowed that his future actions would entirely be on spiritual lines and devoted to the spread of the doctrine of the right conduct.[9] Two years after the Kalinga war, as a primary member of the Buddhist faith, for 265 days, he undertook a nationwide pilgrimage of holy places of Buddhist religion. On his return to Pataliputra, his capital, in 258 BC, after a grand celebration, he launched his missionary campaign throughout his empire and even spread to South India and Sri Lanka. Ashoka's son Mahindra was involved in this mission. In 257 BC, he got the first four of his 14 rock edicts inscribed in different parts of his empire. Out of the fourteen rock edicts, one rock edict has been discovered in Delhi, though not in a complete form.[9]

While edicts inscribed on rocks were found in many parts of the world, erection of carved pillars was unique to Ashokan times, totally independent of any other structures.[10]

Edicts

[edit]

Ashokan edicts are significant for the message they convey on the teachings of Buddhism. They have been found across his empire, written in several languages and scripts, but most of those found in India are written in Prakrit, using the Brahmi script. To spread the message in the north-western of the empire, edicts were written in Kharoshti script. Bilingual and bi-scriptural edicts have also been discovered in Kandahar and Afghanistan, written in Greek and Aramaic. Ashokan edicts written on rocks or pillars are considered unique and permanent as compared to the palm leaf or bark writings (perishable materials) of the past during the Harappan civilization, or even early Mauryan Empire edicts. The Brahmi script was not deciphered until 1837, by James Prinsep, an Indian antiquarian. The edicts of Ashoka deal with codes of conduct in respect of moral and religious views, as his personal messages.[2][11]

The edicts are of two types: the in-situ rock edicts and the pillar edicts, both of which are found in Delhi. The rock edicts are further subdivided into two categories, the "major rock edicts" and the "minor rock edicts", based on their age. Minor rock edits are the earliest, followed by major rock edicts, and then the pillar edicts.[11] Major rock edicts have been discovered across India, with 14 personal declarations by Ashoka. Two have been moved to Delhi from their original locations.[11]

The minor edicts, which predate the major edicts, have been discovered at 17 locations in different regions of the country. Ten of them are categorized as "minor rock edict I" that proclaim Ashoka's religious commitments and urge people to adopt this path. The last seven edicts, include the category of "minor rock edict II" that urges people to be obedient and respectful to parents, elders and teachers. The last seven rock edict include the Delhi edict (found in 1966) that is categorized as minor rock edict I. One particular minor rock edict that is housed in Asiatic Society, Calcutta is a dictum to the Buddhists urging them to read the seven scriptural texts.[11]

The six basic pillar edicts, which are carved on sandstone, deal mainly with the spread of moral values; Ashoka's Dhamma cover topics such as kindness, forbearance, and concern for the welfare of his people. These edicts are fairly uniform in their language and text, unlike the rock edicts, but the Delhi-Topra pillar has a long additional message. It abridges and reaffirms the content of other pillars, and to some degree those of the Major Rock Edicts also.[11]

Rock edict in Delhi

[edit]

The in-situ Bahapur rock edict (28°33′31″N 77°15′24″E / 28.55856°N 77.25662°E) was discovered in Delhi in an engraved form on a small patch of rock exposure in Srinivaspuri, one kilometer north of Kalkaji temple, close to Bahapur village in South Delhi. The edict categorized as a "Minor edict" written in Brahmi script was a first person message of Ashoka, which exhorts people to follow the Buddhist way of life. It is inscribed on a rock surface with irregular lines and letter size with a number of lines not clearly decipherable. The edict translated into English reads:

Beloved of the Gods said thus: (it has been) more than two and a half years since I became a lay devotee.[12] At first no great exertion was made by me but in the last year I have drawn closer to the Buddhist order and exerted myself zealously and drawn in others to mingle with the gods. This goal is not one restricted only to let the people great to exert themselves and to the great but even a humble man who exerts himself can reach heaven. This proclamation is made for the following purpose: to encourage the humble and the great to exert themselves and to let the people who live beyond the borders of the empire know about it. Exertion in the cause must endure forever and it will spread further among the people so that it increases one-and-half fold.[8][13]

The rock edict epigraph was discovered on an inclined rock face by a building contractor operating at the site for building a residential colony. Archaeologists immediately examined it on 26 March 1966 and identified it as representing the Minor Rock Edict I of the Ashokan period in the light of its similarity with edicts in 13 other places in different parts of India, such as Barat in Jaipur division (to which Delhi rock edict has close resemblance) and the two pillars in Delhi. The Delhi edict was recorded as the 14th epigraphic version. The inscription covers an area of size 75 centimetres (30 in) length and 77 centimetres (30 in) height of the rock face. There are ten lines of writing of varying length written in Prakrit language in early Brahmi script and lacks uniformity of the aksharas (letters).[2]

One interpretation for the rock edict at Bahapur in Delhi is that it represents the trans-regional trade route of North India as an ancient trade link between the Gangetic Delta and the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. The second view is that it marks the site of a temple since it has been found at the base of a rock exposure near the present day Kalkaji temple. It is claimed that at Kalkaji, where the new Kalka Mandir (temple) exists now, was the old location of a temple (one of the five temples in Delhi) built by Pandavas, heroes of the epic Mahabharata period.[2][14]

-

Shelter on the surrounding rocky landscape

-

Edict in Delhi surrounded by steel cage

-

Ashoka's Rock Edict (close up)

Pillar edicts in Delhi

[edit]

All of the Ashokan pillar or column edicts were made out of Chunar sandstone quarried from Chunar in the Mirzapur District of Uttar Pradesh. They were chiseled at the quarry and then transported to various places in the country. They were chiseled from massive rock blocks of 1.22 metres (4.0 ft) square and 15.2 metres (50 ft) long, which were extracted from the quarry. They were chiseled as monolith pillars of size between 12.2 metres (40 ft) and 15.2 metres (50 ft) in length with an average diameter of 0.785 metres (2.58 ft).[15] The pillars were cut, dressed, finely polished into circular columns, and carved with edicts, before being transported to various locations in the country. Two were transferred to Delhi in the 14th century by Feroz Shah Tughlaq.[16]

The two pillar edicts are still in Delhi.[17] The one on the Delhi ridge opposite the entrance of Bara Hindu Rao Hospital, close to the Delhi University campus, is popularly known as the Delhi-Meerut Pillar. The other, in the grounds of Feroz Shah Kotla, is known as the Delhi-Topra Pillar.[18][2]

Feroz Shah Tughlaq, who ruled from Delhi as Sultan during the medieval period between 1351 and 1388, was a keen historian, architect, game hunter, and with deep sense of commitment to build public utilities related to irrigation works and establishing urban towns. Feroz Shah, during one of his campaigns, was enthralled by the two spectacular monoliths – inscribed Ashokan pillars he saw, one at Topra near Ambala and the other near Meerut, till then undeciphered – and decided to shift them to his palatial Feruzabad palace in Delhi as "totemic embellishments". He shifted the pillars from these places and got them erected in Delhi; the former in his new capital and the latter on the ridge, near Pir-Ghaib, his hunting palace. The first pillar was erected in the 1350s, next to the Friday mosque in the new city of Feruzabad.).[6][2][19][20] Near the gate of the building that holds the Ashokan pillar, every Thursday afternoon is a kind of djinns date, as a large number of people visit the place to either mollify or revere the djinns or genies (said to be a pre-Islamic belief) that are believed to prowl there.[21]

Delhi-Meerut pillar

[edit]

The Delhi-Meerut pillar (28°40′26″N 77°12′43″E / 28.673853°N 77.211849°E), was shifted from Meerut, in Uttar Pradesh to Delhi by Feruz Shah and erected at a location in the northern ridge of Delhi, close to his hunting palace, between the Chauburji-Masjid and Hindu Rao Hospital. It was an elaborately planned transportation, from its original location, using a 42-wheeled cart to bring it up to the Yamuna river bank and then further transporting it by the Yamuna river route using barges. As seen now, it is of10 metres (33 ft) height but the pillar was damaged in an explosion during the rule of Farrukshiar (1713–19). The five broken pieces were initially shifted to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta and later brought back in 1866 and re-erected in 1887. In the early 17th century, William Finch, a historian chronicler, observed that the pillar had "a globe and half moon at top and diverse inscription upon it".[22][23]

-

Delhi-Meerut pillar

-

Delhi-Meerut pillar inscription

-

Transcription

Delhi-Topra pillar

[edit]

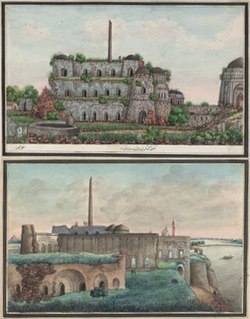

The Topra Ashokan Pillar (28°38′09″N 77°14′43″E / 28.635739°N 77.245398°E), moved from Topra Kalan in Yamunanagar district of Haryana, was erected above the palace building at Feroz Shah Kotla is 13 metres (43 ft) high (with one metre below the platform) and made of sandstone. It is finished very well vis-à-vis the second pillar located in Delhi at the ridge.

The inscription in Brahmi script, which was deciphered by James Prinsep, a renowned scholar in Indian antiquarian studies in 1837, conveys the same message as the other Ashokan Pillars erected such as "code of dharma:virtue, social cohesion and piety" but with one difference that on this pillar there is also a reference to issues related to taxation. The building that houses the pillar is a three-storied structure built in rubble masonry. It has a large number of small domed rooms in the first and second floors, with links to the roof. Rooms on each floor have arched entrances, which are now stated to be used for pujas (worship). It is a pyramidal-shaped structure with reducing size at each level with the pillar installed on the terrace of the building. It is conjectured that originally the pillar had a lion capital (similar to the Ashoka Emblem), which is the National Emblem of India. Feroz Shah is said to have embellished the top of the pillar with frescoes in black and white stone topped with a gilded copper cupola. But at present, what is visible is the smooth polished surface of the pillar, and an elephant carving added much later.[24][25][26] It has also been noted that this pillar, apart from the Ashokan edict, has another set of text inscribed in Sanskrit "below and around Ashokan edict", in nagari script. This inscription records: "the conquests of Visala Deva Vigraharaja IV of the Chauhan dynasty, which was still ruling over Delhi at the time of Ghurid conquests in the 1190s, and his victories over a Mlechha (presumably "Ghaznavid or Gharid"). With this finding, it has been inferred that Visala Deva reused this pillar to record his triumphs in wars.[27]

-

Delhi-Topra Ashoka pillar

-

Inscriptions (Brahmi on top, Devanagari below)

-

Delhi-Topra pillar Ashoka inscriptions (Edicts I to VII)

Transportation techniques

[edit]

The transportation of the massive pillars to Delhi, planned under the direction of Sultan Feruz Shah, was documented by contemporary historian Shams-i-Siraj.[19][28]

The truncated pillar now at the ruined palace of Feruz Shah came from Khizrabad, in the upstream reaches of the Yamuna River, about 90 kilometres (56 mi) from Delhi. The transportation of the pillar was highly demanding, requiring soldiers (both cavalry and foot) to pitch in with all tools and tackles to transport it to Delhi. Silk cotton from the Silk cotton tree, the simal, was gathered in large quantities to surround the pillar before it was lowered horizontally to the ground. The covering was then removed, and replaced by reeds and raw hide to protect the pillar. A 42-wheeled cart was used to transport it to the river bank, where it was loaded onto a large boat. The cart required 8,400 men to move it, 200 to each wheel.[19] A purpose-built palatial building was constructed out of stone and lime mortar to house the pillar. The square base stone was placed at the base of the pillar before the task was completed. The building is now in a ruined state, but the pillar still stands as it was erected.[19][28]

See also

[edit]- Related topics

- Other similar topics

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sharma, pp. 1, 10–11 A glorious chapter to Delhi’s history was added as recently as 1966 with the discovery of an inscription by the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, engraved on a rugged rock, an outcrop of the Arvallis, near Srinivaspuri, west of Kalkaji temple… Direct association of emperor Ashoka (273–236 BC.) of the Maurya Dynasty with Delhi has been brought to light only recently by the discovery of a shorter version of his Minor Rock Edicts carved on a rock near Srinivaspuri. This discovery also indicates that Delhi lay on the trunk route connecting the main cities of ancient India

- ^ a b c d e f g h Singh, Upinder (2006). Delhi. Berghahn Books. pp. 120–131. ISBN 81-87358-29-7. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Peck, p.26. The city is situated where a spur of the Aravalli Hills meets the Yamuna River, and these outcrops were the sites of some early settlements ... Before the 3rd century BC, India was controlled by numerous competing chiefs and kings, and during this time urban centres of some size developed. One of these became the base of powerful Mauryan Empire, created by Chandra Gupta Maurya and consolidated by his grandson Ashoka (reigned 272–232 BC). Ashoka ruled from Pataliputra, modern Patna, but held sway over most of the Indian subcontinent. He aimed at government in a very real sense, controlling the affairs, or at least exhorting a certain way of life, through his famous edicts… However, the most exciting Mauryan discovery, made in 1966 was of an Ashokan Rock Edict found at Kalkaji (East of Kailash), in South Delhi, indicating that there must have been a reasonably important settlement nearby.

- ^ Sharma, pp.1,10–11

- ^ Peck, p.28.The remains of an inscription, on a smooth rock face projecting from the top of a rocky hillock, can be seen under an ugly concrete shelter in a small neighbourhood park in East of Kailash, nor far from the ISKCON temple on the Raja Dhirsain Marg it was discovered in 1966 and is an important part of Delhi’s history and heritage, because it implies that somewhere nearby was a settlement important enough in the 3rd century BC for an edict to have been carved. Among the cluster of religious institutions on the nearby hilltops, the Kalkaji Temple is said to be of great antiquity, and might have had a settlement around it.

- ^ a b Sharma, pp. 1, 10–11

- ^ Peck, p.28

- ^ a b Peck, pp.26–28

- ^ a b c d Kulkae, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (1998). A History of India. CRC Press. pp. 62–65. ISBN 0-203-44345-4. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Bhandarkar pp.205–206">Bhandarkar pp.205–206

- ^ a b c d e Richard Salomon (1998). Indian epigraphy. Oxford University Press US. pp. 135–139. ISBN 0-19-509984-2. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Joshi, M. C.; Pande, B. M. (1967). "A Newly Discovered Inscription of Aśoka at Bahapur, Delhi". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (3/4): 97. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25202984.

- ^ Singh pp.121–122

- ^ Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's tale. by Oxford University Press US. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Bhandarkar p.206

- ^ Bhandarkar pp. 206–207

- ^ "Delhi's air pollution behind corrosion of Ashoka Pillar?". The Times of India. 5 December 2016.

- ^ "Kotla's Ashoka pillar, over 2,000 years old, suffers heavy damage". The Times of India. 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d Keay, John (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Flood p. 248

- ^ Peck p. 82

- ^ Sharma pp.136–137

- ^ Peck p. 91

- ^ Sharma p.131

- ^ Peck p.85

- ^ Horton, Patrick; Richard Plunkett; Hugh Finlay (2002). Delhi. Lonely Planet. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-86450-297-8. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Flood pp.249–250

- ^ a b Bhandarkar pp. 207–209

References

[edit]- Bhandarkar, R. G; D.R. Bhandarkar (2000). Asoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1333-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Flood, Finbarr B. (2009). Objects of Translation. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12594-7.

- Peck, Lucy (2005). Delhi -A thousand years of Building. New Delhi: Roli Books Pvt Ltd. ISBN 81-7436-354-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sharma, Y.D. (2001). Delhi and its Neighbourhood. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)