Delhi-Topra pillar

| Delhi-Topra pillar | |

|---|---|

The Ashokan Pillar on top of the ruined palace of Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi. It was transferred in the 14th century from Topra Kalan in Yamunanagar district, Haryana to Delhi. | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Edicts on sandstone pillars and on in-situ rocks |

| Town or city | Delhi |

| Country | India |

| Coordinates | 28°38′09″N 77°14′44″E / 28.6358346°N 77.2456407°E |

| Construction started | 3rd century BC |

| Completed | 3rd century BC |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Ashoka |

The Delhi-Topra pillar is one of the pillars of Ashoka, inscribed with the moral edicts promulgated by Ashoka, the Mauryan Emperor who ruled in the Indian subcontinent during the 3rd century BCE. The Edicts of Ashoka were either carved on in-situ rocks or engraved on pillars erected throughout the empire. The pillar, originally erected in Topra Kalan, was transferred to Delhi in the 14th century by Feroz Shah Tughlaq.[1]

Pillar edicts in Delhi

[edit]All of the Ashokan pillar or column edicts were made out of Chunar sandstone quarried from Chunar in the Mirzapur District of Uttar Pradesh. They were chiseled at the quarry and then transported to various places in the country. They were chiseled from massive rock blocks of 1.22 metres (4.0 ft) square and 15.2 metres (50 ft) long, which were extracted from the quarry. They were chiseled as monolith pillars of size between 12.2 metres (40 ft) and 15.2 metres (50 ft) in length with an average diameter of 0.785 metres (2.58 ft).[2] The pillars were cut, dressed, finely polished into circular columns, and carved with edicts, before being transported to various locations in the country.[1]

The two pillar edicts are still in Delhi.[3] The one on the Delhi ridge opposite the entrance of Bara Hindu Rao Hospital, close to the Delhi University campus, is popularly known as the Delhi-Meerut Pillar. The other, in the grounds of Feroz Shah Kotla, is known as the Delhi-Topra Pillar.[4][5]

Feroz Shah Tughlaq, who ruled from Delhi as Sultan during the medieval period between 1351 and 1388, was a keen historian, architect, game hunter, and with deep sense of commitment to build public utilities related to irrigation works and establishing urban towns. Feroz Shah, during one of his campaigns, was enthralled by the two spectacular monoliths – inscribed Ashokan pillars he saw, one at Topra near Ambala and the other near Meerut, till then undeciphered – and decided to shift them to his palatial Feruzabad palace in Delhi as "totemic embellishments". He shifted the pillars from these places and got them erected in Delhi; the former in his new capital and the latter on the ridge, near Pir-Ghaib, his hunting palace. The first pillar was erected in the 1350s, next to the Friday mosque in the new city of Feruzabad.).[6][5][7][8] Near the gate of the building that holds the Ashokan pillar, every Thursday afternoon is a kind of djinns date, as a large number of people visit the place to either mollify or revere the djinns or genies (said to be a pre-Islamic belief) that are believed to prowl there.[9]

The Delhi-Topra Pillar was moved from Topra Kalan in Yamunanagar district of Haryana (original location at 30°07′44″N 77°09′35″E / 30.12889°N 77.15965°E), and was erected above the palace building at Feroz Shah Kotla. It is 13 metres (43 ft) high (with one metre below the platform) and made of sandstone.

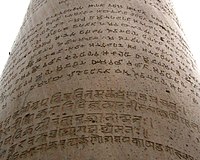

The inscription in Brahmi script, which was deciphered by James Princep, a renowned scholar in Indian antiquarian studies in 1837, conveys the same message as the other Ashokan Pillars erected such as "code of dharma:virtue, social cohesion and piety" but with one difference that on this pillar there is also a reference to issues related to taxation. The building that houses the pillar is a three-storied structure built in rubble masonry. It has a large number of small domed rooms in the first and second floors, with links to the roof. Rooms on each floor have arched entrances, which are now stated to be used for pujas (worship). It is a pyramidal-shaped structure with reducing size at each level with the pillar installed on the terrace of the building. It is conjectured that originally the pillar had a lion capital (similar to the Ashoka Emblem), which is the National Emblem of India. Feroz Shah is said to have embellished the top of the pillar with frescoes in black and white stone topped with a gilded copper cupola. But at present, what is visible is the smooth polished surface of the pillar, and an elephant carving added much later.[10][11][12]

This pillar, apart from the Ashokan edicts, has another set of text inscribed in Sanskrit "below and around Ashokan edict", in nagari script. These are three inscriptions of the 12th century AD, by Visala Deva Vigraharaja IV of the Chauhan dynasty.[13] These inscriptions record the conquests of Visala Deva Vigraharaja IV of the Chauhan dynasty, which was still ruling over Delhi at the time of Ghurid conquests in the 1190s, and his victories over a Mlechha enemy (presumably Ghaznavid or Ghurid).[13] With this finding, it has been inferred that Visala Deva reused this pillar to record his triumphs in wars.[14]

There are also two 16th century inscriptions: a short Sanskrit one by a writer named Ama, and a longer one in a mix of Sanskrit and Persian, mentioning the ruler Ibrahim Lodhi (ruled 1517–1526) of the Lodhi dynasty.[13]

-

Delhi-Topra Ashoka pillar

-

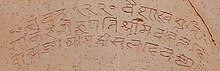

1800 years separate these two inscriptions: Brahmi script of the 3rd century BCE (Edict of Ashoka), and its derivative, 16th century CE Devanagari script (1524 CE, Ibrahim Lodi inscription), on the Delhi-Topra pillar.

-

Delhi-Topra pillar Ashoka inscriptions (Edicts I to VII)

Transportation techniques

[edit]

The transportation of the massive pillars to Delhi, planned under the direction of Sultan Feruz Shah, was documented by contemporary historian Shams-i-Siraj.[7][15]

The truncated pillar now at the ruined palace of Feruz Shah came from Khizrabad, in the upstream reaches of the Yamuna River, about 90 kilometres (56 mi) from Delhi. The transportation of the pillar was highly demanding, requiring soldiers (both cavalry and foot) to pitch in with all tools and tackles to transport it to Delhi. Silk cotton from the Silk cotton tree, the simal, was gathered in large quantities to surround the pillar before it was lowered horizontally to the ground. The covering was then removed, and replaced by reeds and raw hide to protect the pillar. A 42-wheeled cart was used to transport it to the river bank, where it was loaded onto a large boat. The cart required 8,400 men to move it, 200 to each wheel.[7] A purpose-built palatial building was constructed out of stone and lime mortar to house the pillar. The square base stone was placed at the base of the pillar before the task was completed. The building is now in a ruined state, but the pillar still stands as it was erected.[7][15]

See also

[edit]- Topra Ashokan Pillar

- Related topics

- Other similar topics

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Bhandarkar pp. 206–207

- ^ Bhandarkar p.206

- ^ "Delhi's air pollution behind corrosion of Ashoka Pillar?". The Times of India. 5 December 2016.

- ^ "Kotla's Ashoka pillar, over 2,000 years old, suffers heavy damage". The Times of India. 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b Singh, Upinder (2006). Delhi. Berghahn Books. pp. 120–131. ISBN 81-87358-29-7. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Sharma, pp. 1, 10–11

- ^ a b c d Keay, John (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Flood p. 248

- ^ Peck p. 82

- ^ Sharma p.131

- ^ Peck p.85

- ^ Horton, Patrick; Richard Plunkett; Hugh Finlay (2002). Delhi. Lonely Planet. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-86450-297-8. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Singh, Upinder (2006). Delhi: Ancient History. Berghahn Books. p. 208. ISBN 978-81-87358-29-9.

- ^ Flood pp.249–250

- ^ a b Bhandarkar pp. 207–209

References

[edit]- Bhandarkar, R. G; D.R. Bhandarkar (2000). Asoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1333-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Flood, Finbarr B. (2009). Objects of Translation. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12594-7.

- Peck, Lucy (2005). Delhi -A thousand years of Building. New Delhi: Roli Books Pvt Ltd. ISBN 81-7436-354-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sharma, Y.D. (2001). Delhi and its Neighbourhood. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)