Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State

Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State, First Department | |

New York City Landmark No. 0235, 1098

| |

| |

| |

| Location | 35 East 25th Street Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°44′32″N 73°59′12″W / 40.74222°N 73.98667°W |

| Built | 1896–1899[2] |

| Architect | James Brown Lord Rogers & Butler (1952 annex) |

| Architectural style | Late 19th and 20th century revivals, Renaissance Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 82003366[1] |

| NYSRHP No. | 06101.001808 |

| NYCL No. | 0235, 1098 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 26, 1982 |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 11, 1982[3] |

| Designated NYCL | June 7, 1966 (exterior) September 22, 1981 (interior) |

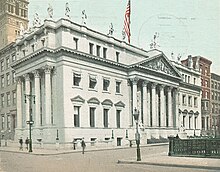

The Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State, First Department, is a courthouse at the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and 25th Street in the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City, United States. The courthouse is used by the First Department of the New York Supreme Court's Appellate Division. The original three-story building on 25th Street and Madison Avenue, designed by James Brown Lord, was finished in 1899. A six-story annex to the north, on Madison Avenue, was designed by Rogers & Butler and completed in 1955.

The facade of both the original building and its annex are made almost entirely out of marble. The courthouse's exterior was originally decorated with 21 sculptures from 16 separate artists; one of the sculptures was removed in 1955. The main entrance is through a double-height colonnade on 25th Street with a decorative pediment; there is also a smaller colonnade on Madison Avenue. The far northern end of the annex's facade contains a Holocaust Memorial by Harriet Feigenbaum. Inside the courthouse, ten artists created murals for the main hall and the courtroom. The interiors are decorated with elements such as marble walls, woodwork, and paneled and coffered ceilings; the courtroom also has stained-glass windows and a stained-glass ceiling dome. The remainder of the building contains various offices, judges' chambers, and other rooms.

The Appellate Division Courthouse was proposed in the late 1890s to accommodate the Appellate Division's First Department, which had been housed in rented quarters since its founding. Construction took place between 1896 and 1899, with a formal opening on January 2, 1900. Following unsuccessful attempts to relocate the court in the 1930s and 1940s, the northern annex was built between 1952 and 1955, and the original courthouse was also renovated. The structure was again renovated in the 1980s and in the 2000s. Throughout the courthouse's existence, its architecture has received largely positive commentary. The Appellate Division Courthouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and its facade and interior are both New York City designated landmarks.

Site

[edit]The Appellate Division Courthouse is in the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City, on the northeast corner of the intersection of Madison Avenue and 25th Street.[4][5] The rectangular land lot covers approximately 14,812 square feet (1,376.1 m2), with a frontage of 98.5 feet (30.0 m) on Madison Avenue to the west and 150 feet (46 m) on 25th Street to the south.[6] The original structure measured 150 feet (46 m) wide along 25th Street, with a depth of 50 feet (15 m) on its western end (facing Madison Avenue) and 100 feet (30 m) on its eastern end.[7]

Madison Square Park is across Madison Avenue, while the New York Merchandise Mart occupies a site directly to the north. Other nearby buildings include the New York Life Building one block north, the Metropolitan Life North Building across 25th Street to the south, and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower one block south.[2][6]

Architecture

[edit]The original three-story Beaux-Arts courthouse, at the corner of Madison Avenue and 25th Street, was built between 1896 and 1899.[4][5] It was designed by James Brown Lord in an Italian Renaissance Revival style with Palladian-inspired details,[8] which include tall columns, a high base, and flat walls.[4] The structure has been likened to an 18th-century English country house because of its Palladian details,[2][9] and it was similar in scale to low-rise residential buildings at the time of its construction.[10] A six-story annex next to the original building on Madison Avenue[11] was designed by Rogers & Butler in 1952.[12]

Sixteen sculptors, led by Daniel Chester French,[13] worked on the courthouse's exterior;[14][15][16] all of the sculptors were members of the then-new National Sculpture Society.[9][13] Lord, with the assistance of the National Society of Mural Painters, commissioned ten artists to execute allegorical murals for the courthouse's interior.[16][17][18] According to the New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services, at the time of the building's construction, it featured decorations by more sculptors than any other edifice in the United States.[19]

Facade

[edit]The facade is made almost entirely of marble. The original marble was quarried from North Adams, Massachusetts, except for small portions quarried from Proctor, Vermont,[20] but this was replaced in 1954 with Alabama marble.[13] A low marble parapet, also installed in 1954, is placed in front of the building at street level.[13] It contains white marble sculptures depicting subjects related to law;[12][5] there were originally 21 sculptures, but one was removed in 1955.[21] The sculptures were treated as a key part of the design, rather than "mere adornment",[22] and they accounted for one-fourth of the total construction cost.[12] While many contemporary buildings in New York City contained niches for statues that were never installed, the statues on the Appellate Division Courthouse were a focal point of the building upon its completion in 1899.[23] The New York Times wrote in 1935 that the courthouse "is said to have more exterior sculpture than any other building in the city".[24]

All of the sculptures were of fictional or dead figures.[25] Although members of the then-prominent Tammany Hall political ring had advocated for the inclusion of sculptures of living people, the artists were against the idea of "a number of pants statues, which at a distance would have looked alike".[12][25] As designed, the building's statues measured 12 feet (3.7 m) tall on average;[26] at the time, such large statues were usually installed on much larger buildings.[23] Many of the statues are installed in pairs and are placed directly above the facade's columns and vertical piers.[27] The freestanding figures were carved out of Lasser marble[14] and cost $20,000 each (equivalent to $732,000 in 2023).[28][29]

25th Street

[edit]The primary elevation of the facade is along 25th Street to the south.[8] At the center of the 25th Street elevation is a portico, which consists of a colonnade of six double-height columns supporting an entablature and a triangular pediment with sculpture. Each of the columns rises above a pedestal and is fluted, with capitals in the Corinthian order.[8][30] The columns measure 24 feet (7.3 m) tall.[31][7] At street level, "two pedestals holding two monumental seated figures"[12] of Wisdom and Force, by Frederick Ruckstull, flank a set of stairs leading to the portico.[32][33][34] Both statues are variously cited as measuring 6 feet 10 inches (2.08 m) tall[14] or 7 feet 6 inches (2.29 m) tall.[35] They each depict a heroically sized male figure; the Force sculpture is of a man wearing armor, while the Wisdom sculpture holds an open book.[35][36]

Recessed behind the columns of the portico are five bays of doorways; the outer two bays are topped by triangular pediments with sculptures, while the center three bays are topped by arched pediments.[8] Maximilian N. Schwartzott designed four sculptures for the triangular pediments,[32][37] which were intended to represent the four periods of the day:[38] The triangular pediment to the left (west) is ornamented with representations of morning and night, while those to the right (east) are ornamented with representations of noon and evening.[8][14][36] The spandrels above these openings are 5 feet (1.5 m) long.[14] There are windows with balustrades on the second story, above the doorways.[8]

On either side of the central portico are four bays of windows with molded frames. Within these bays, the first-story windows have triangular or arched pediments, while the second-story windows are almost square.[8] On the entirety of the 25th Street elevation, the second floor is topped by an entablature and a cornice with modillions and dentils.[39] The third floor is set back slightly and includes rectangular windows, a simple entablature, and a rooftop parapet with sculptures.[40][41] On the pediment is Charles Henry Niehaus's Triumph of Law, a group of five figures.[12][32] The grouping is variously cited as measuring 43 feet (13 m) wide and 9 feet (2.7 m) high,[22] or 32 feet (9.8 m) wide and 14 feet (4.3 m) high.[35] This sculptural group contains icons such as tablets of the law, a crescent moon, a ram, and an owl;[42] the center of the grouping depicts a seated woman flanked by two nude male figures.[35][36]

Madison Avenue

[edit]

The Madison Avenue elevation to the west is narrower than that on 25th Street. The original facade there contains a colonnade of four fluted columns with Corinthian capitals,[30][39] which may have been intended to make that facade look larger.[43] There is a balustrade running between the bottoms of each column. Behind the colonnade, there are arched windows on the first floor and rectangular windows with balustrades on the second floor, similar to the windows in the entrance portico.[39] As on the 25th Street elevation, the second floor is topped by an entablature and a cornice.[39]

The third floor is also set back slightly and is similar in design to that on 25th Street.[40][41] The third-floor windows on Madison Avenue are flanked by four caryatids representing seasons.[40] Thomas Shields Clarke sculpted a group of four female caryatids on the Madison Avenue front, at the third-floor level, representing the seasons.[12][14][37] From left to right are Winter, next to a censer with a flame; Autumn, holding grapes in her hands; Summer, holding a sheaf of wheat and a sickle; and Spring, which is nude to her waist and holding a garland.[44]

The six-story annex north of the original building is made of Alabama marble and was intended to relate to the original courthouse.[12][11] There are plain rectangular windows on each story of the annex except the first story, where the windows are topped with lintels and cornices. In addition, there is a belt course and cornice above the annex's sixth floor.[11]

Roof

[edit]As designed in 1896, the original courthouse's roof is 56 feet (17 m) above ground level.[26][7] On the roof, there are nine freestanding sculptures of figures,[41] depicting historical, religious, and legendary lawgivers.[9][45] These statues are of the same height and proportion, are robed, and appear with various attributes associated with the law, such as book, scroll, tablet, sword, charter, or scepter.[46] Originally, there were ten freestanding sculptures (eight facing 25th Street and two facing Madison Avenue).[45] On Madison Avenue, the northern figure is Philip Martiny's sculpture of the Chinese philosopher Confucius, while the southern figure is William Couper's sculpture of the Hebrew lawman Moses.[44][47] Between Confucius and Moses is Karl Bitter's sculptural group Peace.[40][42][44] This sculptural group consists of a central figure with uplifted arms, flanked by a female and male figure.[35][44][48]

Charles Albert Lopez's Mohammed originally stood on the western end of the 25th Street elevation[36][49] but was removed in 1955 following protests against the image of the prophet from Muslim nations.[40][50] The next sculptures to the east are Edward Clark Potter's Zoroaster, depicting the founder of Zoroastrianism; Jonathan Scott Hartley's Alfred the Great, depicting an Anglo-Saxon king; George Edwin Bissell's Lycurgus, depicting a Spartan legislator; and Herbert Adams's Solon, depicting an Athenian legislator.[36][49] There are three more statues to the east: John Talbott Donoghue's Saint Louis, symbolizing the 13th-century French king; Henry Augustus Lukeman's Manu, symbolizing the author of Manusmriti; and Henry Kirke Bush-Brown's Justinian, symbolizing the 6th-century Byzantine emperor.[51][52] The remaining sculptures on 25th Street were each relocated to the next pedestal to the west after Mohammed was removed,[21][44] and the easternmost pedestal (which originally supported Justinian) was left vacant.[53] The center of the facade contains a sculptural group with three sculptures by Daniel Chester French.[32][34] A female sculpture of Justice is at the center[12][40][49] and is 12 feet (3.7 m) high,[22] while male sculptures of Power and Study stand on either side.[36][40][49][a]

Other sculptures

[edit]The far northern end of the annex's Madison Avenue facade contains a Holocaust Memorial by Harriet Feigenbaum.[54] The memorial was conceived in 1986 by Francis T. Murphy, chief justice of the First Department, who believed that "a symbol of injustice is just as important" to the court as the "symbols of justice" on the original courthouse.[55] Sixty-two artists participated in a design competition for the memorial, with Feigenbaum being selected in 1988.[56] It was dedicated on May 22, 1990.[54][57] The sculpture consists of a map of the Auschwitz concentration camp at its base,[58] as well as a 38-foot-tall (12 m) marble column intended to resemble the smokestack of a Nazi concentration camp.[57]

During 2023, a golden sculpture of a female lawgiver, known as NOW, was temporarily mounted atop the easternmost pedestal on 25th Street.[59][60] Created by Pakistani-American artist Shahzia Sikander, the sculpture was intended to draw attention to gender inequality and gender biases.[61]

Interior

[edit]The first story was built with an 18-foot-high (5.5 m) ceiling, the second story has a 14-foot (4.3 m) ceiling, and the third story has an 11-foot (3.4 m) ceiling. In addition, there are a 10-foot-tall (3.0 m) basement and a sub-cellar.[31][26] Siena marble, onyx, stained glass, and murals are used throughout the courthouse.[10]

The interior has artwork from ten muralists.[17] Henry Siddons Mowbray, Robert Reid, Willard Leroy Metcalf, and Charles Yardley Turner were selected for the murals in the entrance hall, while Edwin Howland Blashfield, Henry Oliver Walker, Edward Simmons, Kenyon Cox, and Joseph Lauber were hired to paint murals in the courtroom.[62][63][64] Alfred Collins had also been hired to design a courtroom mural but was replaced by George W. Maynard at the last minute.[65][66] John La Farge was also hired to review the quality and consistency of the paintings and to adjudicate any artistic disputes that arose.[13][67] The Baltimore Sun wrote that the courthouse was "the only public building in the United States that from the beginning was designed with a view to complete harmony of detail—architectural, mural decoration and sculptural effect".[18] Blashfield later said that he feared the artwork had been overdone because of the massive efforts that went into decorating the building.[67] Specially-designed furniture was made by the Herter Brothers.[5][64][19]

Main hall

[edit]There are three paneled-wood doors leading from the portico on 25th Street to the courthouse's main hall; these doors are topped by tympana, which are also paneled.[68] The main hall measures 50 by 38 feet (15 by 12 m) across[69] and functions as a lobby and waiting area, with leather-and-wood seats designed by the Herter Brothers.[68] The floors were originally made of mosaic tile.[70][38] On the Siena-marble walls are fluted Corinthian piers also made of marble, with lighting sconces attached onto the piers.[68] The north wall of the main hall contains a pair of staircases with openwork railings made of bronze; the stairs lead to the second and third floors.[71] There is also an elevator on the north wall.[68] The hall's ceiling is paneled and coffered, with a bronze-and-glass chandelier and foliate motifs.[13][68] The gold-on-red color of the ceiling was intended to harmonize with the marble used on the walls.[72] During the 20th century, the lobby had busts of lawyers Charles O'Conor and Bernard Botein, but O'Conor's bust was removed in 1982.[73]

Above the marble walls are friezes with murals, which wrap around the room.[40] The north wall contains Mowbray's mural Transmission of the Law, which consists of eight winged figures representing different eras of the history of law, all connected by a scroll.[74][75] Mowbray's figures are painted in green, yellow, and blue[75] and are superimposed on a blue background.[76] Robert Reid's artwork of justice occupies the east wall, as well as the eastern part of the south wall, and depicts various topics, tenets, and types of art.[70][77] Charles Yardley Turner designed two figures, signifying equity and law, above the main entrances on the south wall.[70][77][78] Willard Metcalf's justice artwork occupies the west wall, as well as the western part of the south wall, and depicts personifications of tenets related to justice.[70][77] Reid's and Metcalf's murals are designed in a more modern style and did not rely as much on classical motifs,[76] although the colors used in all three murals harmonized with each other.[79]

Courtroom

[edit]

As designed, the courtroom was placed on the eastern half of the first floor, extending northward to the rear of the building.[80] This may have been motivated by a desire to place the courtroom so it faced away from Madison Square Park.[32] The original design called for the appellate courtroom to measure 46 by 68 feet (14 by 21 m) across.[22][69] The space is decorated with woodwork made by the George C. Flint Company, as well as furniture made by the Herter Brothers.[81] The western wall of the courtroom contains the judges' bench, which is placed on a dais;[79] the bench is curved outward and is elaborately decorated.[70][81] The front portion of the judges' bench contains colonettes and panels. Behind each of the bench's five seats are ornamental panels with scallop-shaped tympana; each panel is separated by engaged columns, and there is an entablature above the columns.[13][81]

There is a wooden balustrade separating the spectators' seats on either side from the court officials' area in the middle.[71] The walls of the courtroom have Siena marble wainscoting interspersed with pilasters of the same material,[70] which in turn are topped by Corinthian capitals.[71] The wainscoting measures 10 feet 9 inches (3.28 m) tall.[34] D. Maitland Armstrong designed several stained-glass windows on the north and south walls; there are marble seating areas beneath each set of stained-glass windows.[81] Above the stained-glass windows on the south wall is a Latin inscription that translates to "Civil Law should be neither influenced by good nature, nor broken down by power, nor debased by money."[82]

At the top of each wall, a frieze runs across the entire room, except on a portion of the eastern wall (directly opposite the bench);[70][34] this frieze measures 4 feet 3 inches (1.30 m) tall.[34] On the eastern wall is a triptych with three panels separated by marble pilasters.[83] From right to left, these panels are Power of the Law by Edwin H. Blashfield; Wisdom of the Law by Henry O. Walker; and Justice of the Law by Edward Simmons.[84][85] All of these panels contain personifications of numerous concepts related to law.[86] George Maynard carved a pair of seals of the city and state governments of New York, with one seal mounted on either side of the triptych.[66][70][84] Both of the seals are supported by figures.[87] The north and south walls are decorated with Judicial Virtues by Joseph Lauber, which consists of eight mural panels depicting virtues on either wall;[88] the leftmost and rightmost panels on either wall depict "four cardinal virtues".[66] Lauber's panels are interspersed with Armstrong's stained-glass windows on these walls.[65][70] On the west wall above the bench, Kenyon Cox designed The Reign of Law, a five-part frieze with figures that signify numerous tenets related to the reign of law,[70][88][89] mostly in a yellow color scheme.[90]

The gilded ceiling is divided into multiple panels and coffers, similar to in the main hall.[79][81] As in the main hall, the gold-on-red color of the ceiling was intended to harmonize with the marble used on the walls.[72] The space is illuminated by a 30-foot-wide (9.1 m) ceiling dome and three large windows,[22] which in turn were designed by Armstrong.[13] The dome bears the names of the Appellate Division's presiding justices.[59] This courtroom's ceiling was protected by a second dome, which extended to a glass dome in the roof.[22] The circumference of the dome contains wrought letters spelling out the names of "past leaders of the American bar" at the time of the building's completion in 1899.[18]

Other spaces

[edit]The lawyers' anteroom is located at the southeastern corner of the building, on 25th Street; most of the room's original decorations are still extant.[71] It is accessed by paneled wooden doors at the southern end of the main hall's east wall. The lawyers' anteroom has elaborate woodwork doorways and window frames, and the plaster ceiling has a frieze and cornice. In addition, there are ornate, paneled coat stalls with decorations such as griffins and finials, and there are stained-glass windows on the north wall (shared with the main courtroom), behind the coat stalls.[81] The anteroom has holes for holding canes and hooks for holding hats, which are illuminated by the stained-glass windows.[67] There is also a lawyers' room next to the waiting room, with similar decorations to the lawyers' anterooms. There are bronze-and-glass lights in both rooms.[71]

Placed on the western half of the ground floor, near Madison Avenue, are the judges' chambers and other rooms,[80] including clerks' and stenographers' offices.[22] A private passage allows judges to access an elevator to the second floor without running into other occupants.[31]

On the second story are the library, judges' quarters, stenographers' room, and bathrooms.[38][70] Each of the judges' quarters has a large antechamber attached to it, and there was also a consultation room.[69] The third floor has one additional judge's quarters due to a lack of space on the second story.[26] There are also janitors' rooms and storage rooms on the third floor.[31][69] The basement, accessed directly from the street, had attendants' rooms,[70] as well as an engine room and a public bathroom.[26] The cellar is used as storage space and a heating plant.[70] To the north of the original courthouse is the six-story annex, which contains additional offices and is connected to the original courthouse by various hallways.[11]

History

[edit]The First Department of the New York Supreme Court's Appellate Division was established in 1894[19][91] and had occupied rented quarters at 111 Fifth Avenue, at the intersection with 19th Street.[12][92] The First Department, the intermediate appellate court serving Manhattan and the Bronx,[19] heard appeals of civil cases. The First Department was the only appellate department in the state with seven judges, as the Appellate Division's other three departments had five judges. Despite this, the First Department was overwhelmed with cases in the late 1890s: it heard over a thousand cases annually, forcing the department to transfer some cases to Brooklyn and consider adding two more justices.[22] Although the department had seven judges, only five would hear cases at any given time;[93] hence, the bench of the current courthouse has five seats.[81]

Development

[edit]Site selection

[edit]

In June 1895, the New York City Sinking Fund Commission approved the Appellate Division's request to rent the third floor of the Constable Building at 111 Fifth Avenue, at the intersection with 19th Street, for two years.[94] The justices wanted to develop a permanent courthouse, and they first looked to the site of the Sixth Avenue streetcar depot between 43rd and 44th streets. The New York City Bar Association was developing its own building on part of the depot site, and the remainder of the lot would have accommodated the court's 50,000-volume library easily.[91]

The justices also considered a site at the intersection of Madison Avenue and 25th Street.[91][94] The latter site was within a 30-minute walk of four of the justices' houses,[91] but the New York City Comptroller thought the site was "rather expensive".[94] At the time, the site at Madison Avenue was occupied by the houses of Henry C. Miner and Edward H. Peaslee.[95][96] A group of commissioners was appointed to assess the 25th Street site before it was acquired through eminent domain. The commissioners determined in April 1896 that Miner's land lot was worth $283,000 and that Peaslee's lot was worth $87,500.[96] The acquisition was approved in spite of the New York City Comptroller's concerns that the valuation of approximately $370,000 was evidence of cronyism.[97] There was a delay in issuing construction contracts due to difficulties in acquiring the site.[98]

Construction

[edit]The justices next received permission from the state government to hire an architect without an architectural design competition.[10] James Brown Lord was hired to design a three-story marble courthouse at a cost of $650,000, with various allegorical statues and porticoes on Madison Avenue and 25th Street.[26][31] Although the justices claimed that they had selected Lord simply because he was the most qualified candidate, Lord's father was a lawyer with the firm of Lord Day & Lord, and his grandfather Daniel Lord had founded that firm.[10] In any case, Lord was paid $3,500 to draw up the initial plans, with the stipulation that he would be retained as supervising architect if his plans were approved.[10] The building plans were jointly approved in June 1896 by the city sinking fund commissioners and the Appellate Division justices.[26][31][15]

Lord organized a committee, which included Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French, to invite select sculptors to design the statuary without a design competition.[67][98] This provoked complaints from some sculptors, including Fernando Miranda y Casellas, who called it an "insulting presumption that only the elect should have a chance to compete".[98] After 16 sculptors had been hired for the project, Lord appointed himself as the chairman of a four-man committee that oversaw the design of the statues.[9] The courthouse's architectural drawings were finally approved in December 1897, at which point the building was expected to cost $700,000.[99] Ten contractors submitted bids for the project later that month.[100][101] Charles T. Wills received the contract for $638,968,[100] less than Lord's estimate of $659,000.[102] Although there were four bids that were lower than Wills's bid, the justices rejected these other bids due to "irregularities".[100]

Lord filed plans for the site with the city's Department of Buildings in March 1898.[80][103] As the site of the courthouse was being excavated, Lord discovered that stone from the site was strong enough to be reused for the courthouse's foundation walls. As a result, he decided not to order brick for the foundations, thereby saving thousands of dollars.[20] On the suggestion of the then-new National Society of Mural Painters, Lord had hired several artists to paint murals in the building by early 1898.[17] The city government authorized the issuance of $897,000 in bonds, including $638,000 for the new courthouse, that June.[104] The next month, the city began looking to sell $10 million worth of bonds, including $390,000 for the courthouse.[105] There was relatively little media coverage of the building during its construction;[37] by March 1899, the courthouse had been completed up to the first floor.[22]

1900s to 1940s

[edit]

Work on the courthouse was nearly complete when, on December 20, 1899, Lord invited a small group of guests, including Appellate Division justices and their friends, to tour the interior.[70][106] The Appellate Division, First Department, had moved the last of its furnishings from its old courthouse on Fifth Avenue by the end of that month.[92] The First Department formally took possession of the new courthouse at 1:00 p.m. on January 2, 1900, with speeches from each of the department's seven justices.[107][108] At the time, only the sculptures on Madison Avenue had been completed.[67] The city's Sinking Fund Commission agreed to pay Wills $1,234 per month until May 1900, when the lighting and the heating plant were supposed to be done.[109] All of the sculptures had been installed by mid-1900, except for the Force and Wisdom statues at the courthouse's main entrance.[25]

The courthouse had cost $633,768, less than the $700,000 that had been budgeted for the project.[102][110] This stood in contrast to other municipal projects like the Manhattan Municipal Building; the Hall of Records; and the Williamsburg, Manhattan, and Queensboro bridges, all of which had gone significantly over budget.[111] The decorations alone cost $211,300, which Lord said was justified by the fact that artwork on public buildings was invaluable to the city.[67] In its early years, the courthouse mainly was used to hear appeals of cases that had been decided by a lower court, such as the New York Supreme Court.[93] The courthouse also hosted bar examinations,[112] as well as other events such as a memorial service for First Department justice Edward Patterson.[113] At the time of the new courthouse's opening, Midtown Manhattan was growing into a business center. Shortly after the Appellate Division Courthouse opened, the lawyer Austen George Fox said that the Appellate Division's relocation had been a "wise move".[114]

Originally, the Appellate Division Courthouse had a 48-foot-tall (15 m) chimney, but this was expanded in 1908 because the construction of a neighboring building blocked the chimney's opening, forcing gas and dirty air back into the courthouse.[115] The courthouse was also used to conduct examinations of the "character and fitness" of prospective lawyers.[116] At the 25th anniversary of the First Department in 1921, the department had heard 30,000 appeals, most in the courthouse.[117][118]

By 1936, there were plans to relocate the Appellate Division's First Department.[119] Mayor Fiorello La Guardia proposed converting the Appellate Division Courthouse into a municipal art center that presented theatrical performances.[119][120] The state acquired a site at 99 Park Avenue (between 39th and 40th Streets)[121] and filed plans for a new appellate courthouse at that site in early 1938,[122] although officials predicted that the new courthouse would not be completed for several years.[123] Plans for the replacement courthouse had been postponed by that October, when funding earmarked for the new courthouse was used instead to finance the construction of the Belt Parkway.[124][125] After the postponement of the replacement courthouse, La Guardia proposed in June 1939 that the Appellate Division Courthouse be converted into a public health museum.[126][127] The city's health commissioner John L. Rice requested $50,000 for the renovation that August.[128][129] The city eventually announced plans in 1949 to sell the site of the replacement courthouse,[130] and the site was acquired by a developer the next year.[131]

1950s expansion

[edit]

In late 1950, the city's public works commissioner Frederick Zurmuhlen approved an $800,000 plan by architecture firm Rogers & Butler to erect a six-story annex to the courthouse. The annex would add 25,200 square feet (2,340 m2) of space, including an enlarged library and six justices' chambers, while the existing building would be retrofitted with two additional justices' chambers. Zurmuhlen also planned to install a steam-and-warm-air heating plant in the existing courthouse, replace the masonry and stone on the facade, add air-conditioning to part of the interior, and repair the roof.[132] Rogers & Butler filed plans for the annex in July 1952, at which point the building was projected to cost $1,184,761;[133] the city borrowed $1.25 million to pay for the project.[134]

The building's sculptures had become rundown by the 1950s, when the New York Herald Tribune reported that some of the sculptures were standing "only by the grace of guy wires".[135] As part of the renovation, Zurmuhlen announced in January 1953 that the sculptures would be taken down.[135][136] A restoration expert had estimated that the cost of replacing the works would be similar to the cost of the building's renovation, which was expected to range from $1.2 million to $1.4 million; restoring the sculptures was planned to cost even more.[136] Instead, Zurmuhlen asked local museums if they wanted the sculptures.[12][28] The Public Works Department received 25 bids for the sculptures from places such as St. Louis and the government of Indonesia.[137] That March, Zurmuhlen announced that the city would spend $8,500 to restore the sculptures.[12][137] Sources disagree on why Zurmuhlen changed his plans for the sculptures; The New York Times cited a survey expressing interest in the sculptures and extensive public opposition to their removal,[12] while the New York Herald Tribune said Zurmuhlen changed his mind after the department conducted a survey of its own.[137]

The governments of three majority-Muslim nations, namely Indonesia, Pakistan, and Egypt, asked the United States Department of State to compel the Appellate Division to remove or destroy the Mohammed sculpture, as some sects of Islam prohibited visual depictions of Mohammed.[29][138] The sculpture's existence was largely unknown before the plans to remove the sculptures were publicly announced.[53] Work on the annex commenced in June 1953 and was completed that September; subsequently, work on the facade began in October 1954 and was completed by 1956.[28] The First Department's justices agreed to permanently remove Mohammed,[21] and the sculptures were all removed and transported to Newark, New Jersey, for restoration.[29] All of the statues were restored and reinstalled, except for Mohammed,[28][29] which ended up in a field in New Jersey.[139] The existing building's offices were completed in June 1955.[28] Workers lowered the ceilings, removed fireplaces and plasterwork, and replaced wood within the original building's offices.[140]

1960s to present

[edit]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) hosted hearings in April 1966 to determine whether the Appellate Division Courthouse should be designated as a city landmark.[141] The building's exterior was designated as a city landmark that June.[4] The city's real-estate commissioner, Ira Duchan, leased 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of the site's unused air rights to the developer of the neighboring New York Merchandise Mart in April 1970; this was the first time that air rights above a city-owned structure had been leased.[142] As part of the agreement, the Merchandise Mart's developer Samuel Rudin agreed to pay out $3.45 million to the New York City government over 75 years.[143] After leasing the air rights, he subleased the courthouse back to the city government.[142] The city also acquired a pair of brownstone residences to the east, intending to expand the courthouse further. The houses were demolished by 1972, with the site being used for parking, but the expansion was canceled in 1979 and the land was sold off three years later.[144]

By the early 1980s, both the facade and interior were deteriorating. Pieces of the sculptures had fallen onto the street, and, in one case, a stained-glass pane fell out of the courtroom's ceiling dome during a trial.[145] The interior of the courthouse was designated a New York City landmark in 1981,[5][4] and the entire building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.[1] The New York City government spent $642,000 during the early 1980s to renovate the sculptures and ceiling dome.[145] A bust of 19th-century lawyer Charles O'Conor was moved from the courthouse's lobby to its basement in 1982 after the First Department's chief justice, Francis T. Murphy, learned that O'Conor had actively opposed freeing black slaves in New York state.[73] Murphy also proposed a Holocaust memorial on the building in 1986;[55] the memorial cost $200,000[58] and was formally dedicated in 1990.[54][57]

Queens–based firm Nab Interiors was hired in 1999 to restore the interior of the courthouse for $1.5 million.[146] Over the next year, architectural firm Platt Byard Dovell White restored the courtroom[2][147] in conjunction with restoration consultant Building Conservation Associates.[147] Once the interior renovations had been completed, Platt Byard Dovell White restored the facade in 2001[147] in collaboration with the Rambusch Decorating Company.[148] The courthouse continues to house the Appellate Division's First Department in the 21st century, although the department had expanded to 16 judges by the 2000s. The department does not hear any jury trials, so only judges, their staff, and lawyers are allowed into the courthouse.[149]

Reception

[edit]At the time of the courthouse's construction, the American Architect and Building News predicted that "the rest of the country will envy New York the possession of this building".[12] The New-York Tribune wrote that the building "will have no peer, it is confidently believed, even among the imposing-looking courts of justice which the Old World is able to present".[22] When the courthouse was nearly finished, The New York Times likened the building to a "handsome modern courthouse" because it had so many murals.[106] The New York World said that the courthouse "gave New York an opportunity to study and admire an example of that new architecture which should fix the type and standard of our public buildings hereafter".[150] The World article likened the courthouse to non-municipal buildings such as the New York Public Library Main Branch and U.S. Custom House, rather than to municipal buildings like the Tweed Courthouse and the City Hall Post Office.[150]

After the courthouse opened, Charles DeKay wrote in The Independent that it "shines like an ivory casket among boxes of ordinary maple".[12][23] DeKay believed that the small size of the Madison Avenue frontage gave the appearance that the building was "part of a larger structure".[89] Richard Ladegast wrote for Outlook that Lord should be "complimented upon his good taste in building, as it were, a frame for some fine pictures and a pedestal for not a few imposing pieces of sculpture".[90] The Scientific American said the courthouse "is the most ambitious attempt yet realized in this country of a highly decorated public building".[45] The same publication described the murals as merit-worthy but too "abstract and philosophical" for an American courthouse.[45] The Municipal Art Society of Baltimore used photographs of the completed courthouse as an inspiration for decorations on Baltimore's then-new Clarence M. Mitchell Jr. Courthouse.[151] One of the courthouse's original justices said the decorators and artists "seem to have conspired with the architect to woo our spirits back from these sombre robes and waft us back to youthful dreams of fairyland".[152]

In 1928, The New Yorker called the building "the rather pleasant little Appellate Court House with its ridiculous adornment of mortuary statuary."[2] The building was featured in a 1977 exhibition, "Temple of Justice", at the clubhouse of the New York City Bar Association.[153] Writing about that show, architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote in The New York Times that the building was "a compendium of classical culture backed up against the featureless glass facade of a recent office tower", the Merchandise Mart.[153] Another New York Times columnist likened the interiors to the "residence of a Middle Western industrialist",[154] while yet another reporter for that paper described the edifice as a "small marble palace".[144] Eric P. Nash wrote in the Times in 1994 that the courthouse's design "details attract the eye and engage the mind", particularly the sculptures and the murals.[155]

Commentary of the building continued in the 21st century. Matthew Postal of the LPC described the building in 2009 as an "outstanding" example of the City Beautiful movement.[5] The historian Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel wrote in 2011 that "the interiors represent a zenith in the synthesis of architecture, decorative arts, and fine arts".[13]

See also

[edit]- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- New York County Courthouse

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ a b "Federal Register: 48 Fed. Reg. 8425 (Mar. 1, 1983)" (PDF). Library of Congress. March 1, 1983. p. 8653 (PDF p. 237). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, p. 369.

- ^ a b c d e f New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79, 332. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b "27 Madison Avenue, 10010". New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Plans for the New Court House". The Sun. July 1, 1896. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 2; National Park Service 1982, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Temple of Justice 1977, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e Tauranac 1985, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 1982, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gray, Christopher (October 24, 1999). "Streetscapes/Appellate Division, 25th Street and Madison Avenue; A Milky White Courthouse With Rooftop Sculptures". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, p. 370.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Adorned With Sculpture: Work of Prominent Artists on the New Appellate Division Court House". New-York Tribune. November 12, 1899. p. C1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574681890. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Temple of Justice 1977, p. 23.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 2; National Park Service 1982, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Temple of Justice 1977, p. 30.

- ^ a b c "Topics in New York: the Dixie With a Crew of Western Farmers Abroad, Fine Mural Decorations, Exhibition of Panels and Friezes in the New Courthouse—Comptroller Coler in Contempt". The Sun. December 22, 1899. p. 5. ProQuest 536148190.

- ^ a b c d "Manhattan Appellate Courthouse". New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Law and Art United: a Magnificent Home for a Dignified Bench". New-York Tribune. December 24, 1899. p. B8, B9, B10. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574687533. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Kifner, John (February 12, 2006). "Images of Muhammad, Gone for Good". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Justice's New Temple: Courthouse of Appellate Division to Be Finished in the Fall". New-York Tribune. March 5, 1899. p. A1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574587041.

- ^ a b c DeKay 1901, p. 1795.

- ^ Harrington, John W. (March 31, 1935). "Statues on the City's Skyline; Effigies Look Down on Throngs in the Streets". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Lawgivers in Marble: Sculptured Decorations of the Appellate Courthouse—remarkable Secrecy as to Their Identity". New-York Tribune. June 3, 1900. p. B9. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570796825.

- ^ a b c d e f g "New Court House Plans: Handsome Structure for Justices of Appellate Division". The New York Times. July 1, 1896. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ DeKay 1901, pp. 1795–1796.

- ^ a b c d e Fernbach, Lyn (February 11, 1956). "11 Court Statues Stay, But Mohammed's Goes". New York Herald Tribune. p. A1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1327599838.

- ^ a b c d Freeman, Ira Henry (April 9, 1955). "Mohammed Quits Pedestal Here On Moslem Plea After 50 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Ladegast 1901, p. 287.

- ^ a b c d e f "A New Courthouse: Headquarters for the Appellate Division to Be at Madison-ave. And Twenty-fifth-st.--plans Approved". New-York Tribune. July 1, 1896. p. 12. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574219231.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e Temple of Justice 1977, p. 25.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.) p. 205

- ^ a b c d e "Court House Decorations". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 21, 1899. p. 5. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Symbolized by Statues: Ideas Expressed by the Sculpture on the New Appellate Courthouse". New-York Tribune. January 7, 1900. p. C6. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570746152.

- ^ a b c d e f Temple of Justice 1977, PDF p. 46.

- ^ a b c "New York's New Court House". Stone. Vol. 20, no. 1. December 1, 1899. p. 80. ProQuest 910625870.

- ^ a b c "New Home of Appellate Court Entirely of Marble". The World. December 21, 1899. p. 8. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, pp. 2–3; National Park Service 1982, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 3; National Park Service 1982, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Temple of Justice 1977, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Ladegast 1901, p. 290.

- ^ Ladegast 1901, p. 286.

- ^ a b c d e Temple of Justice 1977, PDF p. 47.

- ^ a b c d "The Appellate Court-house in New York". Scientific American Building Edition. Vol. 31, no. 4. April 1, 1901. p. 61. ProQuest 88790664.

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Ladegast 1901, pp. 290–291.

- ^ DeKay 1901, pp. 1797–1798.

- ^ a b c d Ladegast 1901, p. 289.

- ^ Plate, S. Brent. Blasphemy: Art That Offends. London: Black Dog, 2006. ISBN 978-1-904772-53-8, p. 108

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, PDF pp. 46–47.

- ^ Ladegast 1901, pp. 289–290.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (January 10, 2015). "A Statue of Muhammad on a New York Courthouse, Taken Down Years Ago". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Appellate Division – First Judicial Department". New York State Unified Court System. September 23, 2020. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Anderson, Susan Heller; Dunlap, David W. (July 31, 1986). "New York Day by Day; Judges Seek Symbol of Injustice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Cummings, Cecilia (July 27, 1988). "A Memorial to Holocaust Is Approved". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Harris, Lyle V. (May 23, 1990). "Dedication of Memorial Brings Calls for Harmony". Daily News. p. 548. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Fox, Margalit; Robinson, George (June 22, 2003). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Bilefsky, Dan (January 25, 2023). "Move Over Moses and Zoroaster: Manhattan Has a New Female Lawgiver". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ Heim, Mark (January 26, 2023). "New York courthouse abortion statue honoring Ruth Bader Ginsberg called 'satanic golden medusa'". Al.com Alabama. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ Culgan, Rossilynne Skena (January 20, 2023). "For the first time, a statue of a woman sits atop this Manhattan courthouse". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division / First-Fourth Departments Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Historical Society of the New York Courts.

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, pp. 30–35.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Temple of Justice 1977, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Ladegast 1901, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d e f Tauranac 1985, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d "Talk on Hindu Folk-lore; Prof. Lanman of Harvard Lectures Before the Comparative Literature Society". The New York Times. March 5, 1899. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "View of New Courthouse: Invited Guests See Interior of Appellate Division's Home". New-York Tribune. December 21, 1899. p. 4. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574689812.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 4; National Park Service 1982, p. 4.

- ^ a b Ladegast 1901, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Sutton, Larry (November 16, 1982). "Court-lobby Hero is Just a Bust". Daily News. p. 166. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Ladegast 1901, p. 291; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 3; Temple of Justice 1977, PDF p. 48.

- ^ a b Ladegast 1901, p. 291.

- ^ a b Temple of Justice 1977, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 3; Temple of Justice 1977, PDF p. 48.

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c DeKay 1901, p. 1798.

- ^ a b c "Of Interest to the Building Trades". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 61, no. 1565. March 12, 1898. p. 458 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 4.

- ^ DeKay 1901, pp. 1800–1802.

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, p. 31.

- ^ a b DeKay 1901, pp. 1798–1799; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 4; Temple of Justice 1977, PDF p. 48.

- ^ Ladegast 1901, pp. 292–295.

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, pp. 31–33.

- ^ DeKay 1901, p. 1799.

- ^ a b Ladegast 1901, p. 292; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1981, p. 4; Temple of Justice 1977, PDF p. 48.

- ^ a b DeKay 1901, p. 1802.

- ^ a b Ladegast 1901, p. 296.

- ^ a b c d Tauranac 1985, p. 50.

- ^ a b "Court to be Held in New Home". The World. December 30, 1899. p. 9. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Howland, Henry E. (October 1901). "The Practice of the Law in New York". Century Illustrated Magazine. Vol. LXII, no. 6. p. 816. ProQuest 125504790.

- ^ a b c "Quarters for Appellate Court; Lease of Rooms in the Constable Building Authorized by the Sinking Fund Commissioners". The New York Times. June 29, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ "New Court Site Not Selected". The New York Times. August 6, 1895. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Gossip of the Week". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 57, no. 1464. April 4, 1896. p. 571 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Tauranac 1985, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b c "Sculptors Ask Competition; They Protest Against Awards of Work Without Bids. The Decoration of the New Appellate Division Court House Likely to Create a Great Deal of Bad Feeling". The New York Times. February 17, 1897. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ "New Courthouse Plans Approved: the White Marble Building to Be Erected for the Appellate Division to Cost $700,000". New-York Tribune. December 7, 1897. p. 3. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 574378195.

- ^ a b c "Public Buildings". The Construction News. December 29, 1897. p. 741. ProQuest 128392124.

- ^ "Canalmen Want Relief; They Charge, the Standard Oil Trust with Discrimination Against New York". The New York Times. December 21, 1897. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Tauranac 1985, pp. 51–52.

- ^ "Article 3 – No Title". The Construction News. Vol. 6, no. 11. March 16, 1898. p. 258. ProQuest 128395332.

- ^ "Rapid Transit Meeting; Rentals on Proposed New Lines of the Manhattan Considered". The New York Times. June 10, 1898. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ "The Bond Sale". The Sun. July 27, 1897. p. 6. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "New Court House Opened; Private View of the Home of the Appellate Division". The New York Times. December 21, 1899. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ "Court's New House Open: Appellate Division Takes Formal Possession of the Building Provided for It". New-York Tribune. January 3, 1900. p. A1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 570798263.

- ^ "The New Appellate Court; Justices Have a Housewarming with Greetings from the Bar". The New York Times. January 3, 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Court to Occupy Its New Home". The New York Times. December 29, 1899. p. 12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Appellate Division – First Judicial Department". www.nycourts.gov. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ "Calls Court House Mad Extravagance; Strong Protest to Board of Estimate from the Real Estate Board". The New York Times. June 14, 1915. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Terribly Burned by Pitch.: Three Men Spattered With the Blazing Liquid in a Brewery". The New York Times. July 13, 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Tribute to Justice: Bar Association Memorial for Edward Patterson". New-York Tribune. March 31, 1910. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 572300908.

- ^ "Move for an Up-town County Court House; Austen G. Fox to Offer a Resolution to the Bar Association. His Reasons for Urging a Removal to Some Point North of Fourteenth Street – Possible Opposition of Realty Interests". The New York Times. March 5, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Attacks Uncle Sam as Soft Coal User; Citizen Hallock Wants to Know Why Post Office Disobeys the Law". The New York Times. July 11, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ See, for example:

- "Names 192 Seeking Admission to Bar; Committee on Character and Fitness Requests Information Regarding Candidates". The New York Times. February 25, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- "Class of 271 Called in Bar Fitness Test; Eleven Women Included Among Applicants Summoned for Examination Oct. 18". The New York Times. October 11, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Appellate Division Has 25th Birthday; Root Defends Plan of Assigning Up-State Justices Here, for Good of the Law". The New York Times. January 5, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Appellate Court's 25-Year Record Is Extolled by Root: Principal Speaker at Anniversary of Founding of Tribunal Says Bar Generally Agrees With Decisions". New-York Tribune. January 5, 1921. p. 19. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 576378374.

- ^ a b "Mayor Offers Site for an Art Center; Would Convert the Appellate Courthouse When Tribunal Goes to New Quarters". The New York Times. May 2, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Mayor Reveals Art Center Plan To Clubwomen: Tells Convention He Aims to Utilize Courthouse at Madison Av. and 25th St". New York Herald Tribune. May 2, 1936. p. 11. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1258046166.

- ^ "Henry St. Nurses Buy Loew House; Old Murray Hill Dwelling Will Be Occupied as Executive Offices". The New York Times. March 25, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Plans for Court Filed; New Home of Appellate Division on Park Ave. to Cost $3,000,000". The New York Times. January 20, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "State Chamber Asks Court House Delay; Letter to Mayor and Estimate Board Cites City Finances". The New York Times. May 18, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "City Adopts $28,000,000 Moses Parkway Program After Warning by Mayor". New York Herald Tribune. October 14, 1938. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1259279225.

- ^ "New York; Parks and Dumps The Moses Record Another Dewey? Mr. Geoghan Under Fire Circumferential' Drive". The New York Times. October 16, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Porter, Russell B. (June 18, 1939). "Health Museum Planned in Courthouse at Madison and 25th". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Fair's Museum Of Health Gets Mayor's Praise: Dedicates Building and Proposes Permanent City Exhibit in Old Courthouse". New York Herald Tribune. June 18, 1939. p. 22. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1243017240.

- ^ "Health Bureau Asking $50,000 For a Museum: Rice Proposes Remodeling Old Appellate Building to Hold Exhibits After Fair". New York Herald Tribune. August 16, 1939. p. 8. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1252310378.

- ^ "Welfare and Health Bureaus Ask A Wide Expansion of Services; Hodson in Budget Seeks 15 New Centers to Cost $8,923,000 and Rice Proposes 14 and 22 Substations at $7,450,000". The New York Times. August 16, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Midtown Park Ave. Plot To Be Auctioned by City". New York Herald Tribune. December 16, 1949. p. 42. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1336615448.

- ^ "Big Site Sold at City Auction; Syndicate Pays $1,875,000 for Park Ave. Plot—Plans a 25-Story Building". The New York Times. January 25, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Plan for Addition to Court Approved; Zurmuhlen Orders Final Draft for $800,000 Structure for Appellate Division". The New York Times. November 7, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Building Plans Filed; Appellate Courthouse Addition Estimated at $1,184,761". The New York Times. July 3, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Planning Agency Backs West Side Home Project". New York Herald Tribune. June 26, 1952. p. 23. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1319927733.

- ^ a b Boardman, Robert C. (January 13, 1953). "For Sale: 12 Big Statues Atop Courthouse". New York Herald Tribune. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322291990.

- ^ a b "Statuary Solons May Be Retained; Zurmuhlen Calls for Study of the Cost of Rehabilitation of Figures on Courthouse". The New York Times. January 28, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Statues to Stay On Appellate Court Building: Public Works Dept. Bows to Public Opinion, Limits Renovation to $8,500". New York Herald Tribune. January 13, 1953. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322486020.

- ^ "Statue Removed". South China Sunday Post-Herald. April 10, 1955. p. 7. ProQuest 1769201699.

- ^ Johnston, Laurie; Anderson, Susan Heller (June 7, 1983). "New York Day by Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Temple of Justice 1977, p. 45.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (April 13, 1966). "Seminary in Chelsea Fights Historic Designation; Saying Its Property Would Be Restricted, It Invokes Right to Freedom of Religion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Burks, Eward C. (April 26, 1970). "City Wants Air Rights To Hop, Skip and Jump". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Burks, Edward C. (April 16, 1970). "City Granting Leases on Its Buildings' Air Rights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Oser, Alan S. (May 24, 1985). "New 42-Story Structure Off Madison Square Park". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 24, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (May 23, 1983). "Embellished Courthouse is Regaining Its Splendor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "New York". Engineering News-Record. Vol. 22, no. 23. June 14, 1999. p. 88. ProQuest 235681457.

- ^ a b c Dunlap, David W. (July 15, 2001). "A Future for Madison Square's Past". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ McGinity, Meg (April 10, 2000). "Renovator deconstructs itself to reconstruct after bankruptcy". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 16, no. 15. p. 38. ProQuest 219128349.

- ^ Robbins, Tom (July 25, 2007). "Benchwarmers". The Village Voice. p. 18. ProQuest 232284906.

- ^ a b "The New Architecture in New York". The World. December 22, 1899. p. 18. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Baltimoreans Invited to Dine Here". New-York Tribune. December 30, 1899. p. 9. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ Tauranac 1985, p. 53.

- ^ a b Huxtable, Ada Louise (July 24, 1977). "A Temple Of Justice That Inspires". The New York Times. p. D19. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 123461809.

- ^ Lowe, David (March 15, 1979). "Design Notebook". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Nash, Eric P. (December 4, 1994). "Style; Law and Mortar". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

Sources

- Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of the State of New York, First Department, Interior (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 27, 1981.

- Appellate Division Courthouse (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 18, 1982.

- Architectural League of New York; Association of the Bar of the City of New York (July 22, 1977). "Temple of Justice—the Appellate Division Courthouse" (PDF). nycourts.gov.

- DeKay, Charles (August 1, 1901). "The Appellate Division Court in New York City". The Independent. Vol. 53, no. 2748. pp. 1795–1802. ProQuest 90533646.

- Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee (2011). The Landmarks of New York (5th ed.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 369–370. ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- Ladegast, Richard (February 2, 1901). "A Beautiful Public Building". Outlook. Vol. 67, no. 5. pp. 286–296. ProQuest 136601128.

- Tauranac, John (1985). Elegant New York. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-89659-458-6. OCLC 12314472.

External links

[edit]- New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- Government buildings completed in 1899

- Courthouses on the National Register of Historic Places in New York City

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Flatiron District

- 1899 establishments in New York City

- Sculptures by Daniel Chester French

- New York City interior landmarks

- New York State Register of Historic Places in New York County