Allenby Formation

| Allenby Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Ypresian | |

Alternating Princeton Chert and coal sequences | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Princeton Group, Eocene Okanagan Highlands |

| Sub-units | Princeton Chert, Vermillion Bluffs Shale |

| Overlies | Cedar Formation |

| Area | 300 km2 (120 sq mi)[1] |

| Thickness | 1,860–2,100 m (6,100–6,890 ft)[1] |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale, sandstone |

| Other | Coal–breccia, coal–chert |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 49°22.6′N 120°32.8′W / 49.3767°N 120.5467°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 53°06′N 107°30′W / 53.1°N 107.5°W |

| Region | British Columbia |

| Country | |

| Extent | Princeton Basin & Tulameen basin |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Allenby, British Columbia |

| Named by | Shaw |

| Year defined | 1952 |

The Allenby formation is a sedimentary rock formation in British Columbia which was deposited during the Ypresian stage of the Early Eocene. It consists of conglomerates, sandstones with interbedded shales and coal. The shales contain an abundance of insect, fish and plant fossils known from 1877 and onward, while the Princeton Chert was first indented in the 1950s and is known from anatomically preserved plants.

There are several notable fossil producing localities in the Princeton & Tulameen basins. Historical collection sites included Nine Mile Creek, Vermilian Bluffs, and Whipsaw Creek, while modern sites include One Mile Creek, Pleasant Valley, Thomas Ranch, and the Princeton Chert.

Extent and correlation

[edit]The Allenby is estimated to have an overall extent of approximately 300 km2 (120 sq mi), though actual outcroppings of the formation make up less than 1% of the formation, while other exploratory contact is via boreholes and mines. The half-graben which contains the formation is separated into two major depositional basins, the Princeton basin around Princeton, British Columbia and the Tulameen basin centered approximately 17 km (11 mi) west. The grabens extensional faults at the eastern side of the basin place the hanging wall Allenby strata in contact with much older foot wall strata of the Nicola Formation which dates to the Upper Triassic.[1][2][3]

The Allenby Formation is the southern-most of the Eocene Okanagan Highlands lakes in British Columbia, and second most southern site after the Klondike Mountain Formation of Republic, Washington and northern Ferry County. In British Columbia, the formation is coeval to the Tranquille Formation, known from the McAbee Fossil Beds and Falkland site, the Coldwater Beds, known from the Quilchena site, and Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park. The highlands, including the Allenby Formation, have been described as one of the "Great Canadian Lagerstätten"[4] based on the diversity, quality and unique nature of the biotas that are preserved. The highlands temperate biome preserved across a large transect of lakes recorded many of the earliest appearances of modern genera, while also documenting the last stands of ancient lines.[4]

The warm temperate uplands floras of the Allenby Formation and the highlands, associated with downfaulted lacustrine basins and active volcanism are noted to have no exact modern equivalents, due to the more seasonally equitable conditions of the Early Eocene. However, the formation has been compared to the upland ecological islands in the Virunga Mountains within the Albertine Rift of the African rift valley.[5]

The earliest work in the region was on exploratory expeditions in 1877 and 1878, with fossils collected in the areas of Nine-Mile Creek, Vermilian Bluffs on the Similkameen River, and Whipsaw Creek. While reporting on additional plant fossils collected from British Columbia, Penhallow (1906) noted the likely coeval status of the Princeton basins with many of the sites now considered the Okanagan Highlands.[6] Modern collecting has centered on the areas around One Mile Creek, Pleasant Valley, and Thomas Ranch.[2]

Age

[edit]The age estimates for the Allenby Formation have varied a number of times since the first explorations happened in the 1870s. Shaw (1952) dated the formation as Oligocene, an age followed by Arnold (1955).[7][8] Half a decade later, the older age of 48 ± 2 million years old was first suggested, with a younger age being suggested at 46.2 ± 1.9 million years old in 2000 and an older date of 52.08 ± 0.12 million years ago obtained from uranium–lead dating of zircons from Vermilion Bluffs shale in 2005.[1]

Lithology

[edit]The Allenby is composed of cyclical sedimentation events that were deposited along the course of a river-system in conjunction with depositional areas from nearby lakes and wetlands. Coeval volcanic eruptive events are recorded as interbeds of tephras and lavas, while the riverine course is marked with depositional areas of conglomerates and sandstones. The quieter environments are noted for finer layers of shales and coalified layers.[1]

The coal seams throughout the formation are typically sub-bituminous.[1]

Notable in conjunction with the coal seams are sections of chert which formed during silica rich periods. The rapid cyclical changes from coal to chert and back are not noted in any other fossil locality in the world. An estimated 49 coal-chert cycles are known, though the exact conditions for this process are not well understood. Silica rich volcanic episodes in the region during deposition would have been needed for formation of the cherts, while slowly moving waters and gently subsiding terrains would be needed for the peats and fens to accumulate. Rates of organic deposition in swamps have been estimated at 0.5–1 mm (0.020–0.039 in) in modern temperate climates, this suggests the time needed for each 10–20 cm (3.9–7.9 in) chert layer would be at least 100 years or more, with the full sequence of cycles taking place over no more than 15,000 years.[1]

Palynoflora

[edit]Palynological analysis of samples from the Thomas ranch site by Dillhoff et al. (2013) resulted in the identification of 32 pollen and spore types that were assignable to family or genus level, with a total number of distinct pollen and spore types, including unassignable morphotypes, number over 70. The predominant pollens of the site are conifers, which make up between 85%–97% of the total pollens, while the angiosperm pollens are dominated by members of Betulaceae.[2]

Several pteridophyte families and genera are represented as spore fossils alone, without corresponding megafossil records, including Lycopodiaceae, Osmundaceae, and Schizaeaceae. Similarly, at least three additional conifer genera are only present as pollen fossils and up to 12 angiosperms are present in the pollen record. Sometimes considered a Biostratgraphic index fossil, the angiosperm palynospecies Pistillipollenites macgregorii has been recovered from several sites in the Allenby Formation, while the palynospecies Erdtmanipollis pachysandroides is rare, having only been reported from the formation twice.[2]

| Family | Genus | Species | Pollen/Macrofossil | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A holly palynomorph |

|||

|

Pollen |

A palm palynomorph |

||||

|

Pollen |

A box family palynomorph |

||||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

An alder palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A birch palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A hornbeam palynomorph |

|||

|

unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A hazelnut palynomorph |

|||

|

unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Cunninghamia like palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A redwood palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A Taxodioideae subfamily palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

An elaeagnaceous palynomorph, similar to oleaster |

|||

|

unidentified |

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

An ericaceous palynomorph of uncertain affinity |

||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A chestnut palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[9] |

Pollen |

A fagaceous palynomorph |

|||

|

"Fagus Pollen type 3"[9] |

Pollen |

A beech palynomorph |

|||

|

"Fagus Pollen type 2"[9] |

Pollen |

A beech palynomorph |

|||

|

Pollen |

A fagaceous palynomorph |

||||

|

"Quercus Pollen type 1"[9] |

Pollen |

An oak palynomorph, similar to Quercus Group Lobatae pollen |

|||

|

"Quercus Pollen type 2"[9] |

Pollen |

An oak palynomorph, ancestral type with Quercus Group Ilex morphology |

|||

|

Unidentified[9] |

Pollen |

A fagaceous palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified |

Unidentified[9] |

Pollen |

A Fagoideceous palynomorph |

||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

||||

|

Pollen & macrofossils |

A Gingko palynomorph |

||||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A sweet gum palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A hickory palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A hickory palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A lycopod palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A linden palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

An osmundaceous fern palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A fir palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A pine family palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Picea palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A Pinus palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A pine family palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A Pseudolarix palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Tsuga palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Laricoidae palynomorph, similar to larch |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Laricoidae palynomorph, similar to pseudotsuga |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Platanus palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A Potamogeton palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified |

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

Rose famnily palynomorphs |

||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A willow palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A duck weed palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A maple palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

A horse chestnut palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified |

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A sapotaceous palynomorph |

||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen |

A yew palynomorph |

|||

|

Unidentified[2] |

Pollen & macrofossils |

An elm palynomorph |

|||

|

Pollen |

A palynomorph of uncertain affinity, possibly a Gentianaceae or Euphorbiaceae species |

Compression paleobiota

[edit]A group of six mosses were described from the Allenby Formation by Kuc (1972, 1974) representing the genera Ditrichites, Hypnites and Plagiopodopsis, with two species placed in the morphogenus Muscites.[10][11] Dillhoff et al. (2013) identified twelve distinct gymnosperm taxa spanning the families Cupressaceae, Ginkgoaceae, and Pinaceae. While being the minority component of the Thomas Ranch flora by total fossil numbers, angiosperms have a higher diversity, with 45 distinct morphotypes represented as foliage, reproductive structures, or both. Seventeen of the morphotypes are identifiable to genus or species, with members of the family Betulaceae being most prominent. At least common one leaf type is suggested to possibly represent an extinct plant order, but has not been described.[2] Only two pteridophyte species have been described from the compression flora, Azolla primaeva by Penhallow (1890) and Equisetum similkamense by Dawson (1878).[12][8]

The following fossil conifers, pteridophytes, ginkgophytes and bryophytes have been described from the Allenby Formation:

Bryophytes

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(Kuc) Miller |

An amblystegiaceous moss |

||||

|

(Kuc) Miller |

An amblystegiaceous moss |

||||

|

(Kuc) Miller |

A bartramiaceous moss |

||||

|

Kuc |

|||||

|

incertae sedis |

Kuc |

A moss of uncertain placement |

|||

|

incertae sedis |

Kuc |

A moss of uncertain placement |

Pteridophytes

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

|

A mosquito fern |

|

Gingkophytes

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A ginkgo |

| ||||

|

Mustoe, 2002 |

A ginkgo with highly dissected leaves |

|

Pinophytes

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(Lesquereux) MacGinitie |

|||||

|

First identified as "Sequoia" brevifolia, "S." heeri. "S." langsdorfii (in part), "S." nordenskiöldi, & Taxodium distichum miocenum (in part) |

| ||||

|

Lesquereux |

A redwood |

| |||

|

First identified as "Sequoia" angustifolia, |

|||||

|

Oldest true fir described |

| ||||

|

Undescribed[15] |

A spruce |

||||

| |||||

|

A pinaceous winged seed |

|||||

|

Dawson, 1890 |

|||||

|

(J.Nelson) Rehder |

Originally identified as Pseudolarix americana,[15] then as Pseudolarix arnoldii[18] |

||||

|

Gooch |

|

Angiosperms

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Wolfe & Wehr |

A sumac |

| |||

|

Pigg, Bryan, & DeVore |

An onion relative |

| |||

| |||||

|

(Berry) Wolfe & Wehr |

An Alder |

| |||

|

Wolfe & Wehr |

A birch |

| |||

|

Pigg, Manchester, & Wehr |

A coryloid genus |

||||

|

(Dawson) Wolfe & Wehr |

A katsura |

| |||

|

(Knowlton) Wolfe & Wehr |

A beech |

| |||

|

Undescribed[2] |

A beech species Not described to species | ||||

|

Undescribed[2] |

A gooseberry species |

||||

|

Radtke, Pigg & Wehr |

A winter-hazel species |

| |||

|

Undescribed[23] |

A wingnut |

||||

|

Undescribed[23] |

A laural species |

||||

|

Berry |

A laural species |

| |||

|

Undescribed[24] |

An extinct sterculioid flower |

||||

| |||||

|

Wolfe & Wehr |

A dove-tree relative |

| |||

|

Undescribed[2] |

Manchester |

A sycamore morphospecies |

|||

|

(Lesquereux) Wolfe & Wehr |

A sycamore |

| |||

|

Unidentified[25] |

A service berry |

||||

|

A snow wreath |

|||||

|

A Sorbarieae genus |

|||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

Wolfe & Tanai |

A maple |

||||

|

McClain and Manchester |

A Dipteronia species |

| |||

|

Pigg et al. |

A Tetracentron relative |

| |||

|

Undescribed[2] |

A trochodendraceous species |

||||

|

Denk & Dillhoff |

An elm |

| |||

|

Undescribed[5] |

|||||

|

(Lesquereux) Wang & Manchester |

A sapindalean flower of uncertain affiliations |

|

Mollusks

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

A hydrobiid mud snail |

||||

|

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

A lymnaeine pond snail |

||||

|

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

An aplexine bladder snail |

||||

|

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

A physine bladder snail |

||||

|

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

An ancylinine ramshorn snail |

||||

|

Indeterminate[32] |

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

A possible planorbinine ramshorn snail |

|||

|

Indeterminate[32] |

L.S. Russell, 1957 |

A possible sphaeriine fingernail clam |

Insects

[edit]Coleopterans

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unidentified |

Unidentified[33] |

A soldier beetle |

|||

|

Unidentified |

Unidentified[33] |

A caraboid superfamily beetle |

|||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

(1890 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

(1890 illustration) | ||||

|

Undescribed[34] |

Scudder, 1895 |

A click beetle |

(1890 illustration) | ||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

| ||||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

(1890 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

(1890 illustration) |

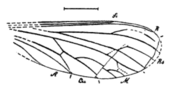

Dipterans

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rice, 1959 |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

Rice, 1959 |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

Rice, 1959 |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A marchfly Penthetria lambei (1910), Penthetria ovalis (1910), & Penthetria separanda (1910) considered junior synonyms (1959) |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Scudder, 1879) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

Rice, 1959 |

A marchfly |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A long-legged fly |

(1910 illustration) | |||

|

Handlirsh, 1909 |

(1910 illustration) | ||||

|

(Handlirsh, 1910) |

A cranefly |

|

Hemipterans

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Handlirsch, 1910 |

(1910 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Undescribed[40] |

Scudder, 1895 |

A spittlebug |

|||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

(1890 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Undescribed[40] |

Scudder, 1895 |

A froghopper |

|||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1895 |

(1895 illustration) | ||||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

(1890 illustration) | ||||

|

Undescribed[40] |

Scudder, 1895 |

A fulgorid plant hopper |

|||

|

(Scudder, 1879) |

A gerrine water strider |

(1890 illustration) | |||

|

Scudder, 1879 |

A hemipteran of uncertain placement |

(1890 illustration) |

Hymenopterans

[edit]Archibald, Mathewes, & Aase (2023) reported a Titanomyrma species ant queen from the Vermillion Bluffs site, and noted the range extension for Formiciinae into the highlands, as the subfamily was previously considered a strictly thermophilic ant group. Due to complications arising from preservational distortion during diagenesis, they were unable to determine the correct size of the queen in life. If the distortion was lateral, then compression to bilateral symmetry yielded an adult length of approximately 3.3 cm (1.3 in), placing it the same range as Formicium berryi and F. brodiei, known only from wings, and sugg4ested as possible males. Conversely stretching the fossil to bilateral symmetry results in a larger 5 cm (2.0 in) length estimate, placing it as comparable to queens of T. lubei and T. simillima.[41]

| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Undescribed[35] |

A braconid wasp |

(1890 illustration) | |||

|

Indeterminate[41] |

A formiciine titan ant |

| |||

|

(Handlirsch, 1910) |

A xoridine ichneumon parasitic wasp |

| |||

|

Rice, 1968 |

|

Mecopterans

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Archibald, 2005 |

|||||

|

Archibald & Rasnitsyn, 2018 |

Neuropterans

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(Scudder, 1895) |

A Polystoechotid-group giant lacewing[46] |

(1895 illustration) |

Odonata

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Indeterminate |

Indeterminate[47] |

A daner dragonfly |

|||

|

Archibald & Cannings, 2022 |

A possible Dysagrionidae odonate. |

|

Raphidiopterans

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authority | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Archibald & Makarkin, 2021 |

Vertebrates

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authors | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Wilson, 1982 |

A bowfin |

| |||

|

Aves incertae sedis |

Unidentified |

Unidentified[50] |

Mayr et al., 2019 |

Indeterminate feathers and a skeleton |

|

|

(Cope, 1893) |

A catostomid sucker |

||||

|

(Marsh, 1874) |

A tillodont species |

||||

|

(Hussakof, 1916) |

A mooneye |

||||

|

Wilson, 1977 |

A percopsiform fish |

||||

|

Wilson, 1977 |

An ancestral salmon |

||||

|

Undescribed[57] |

A soft shelled turtle |

Princeton Chert biota

[edit]The Princeton chert biota is unique in the Allenby formation due to the silicification of the chert, which has resulted in cellular and anatomical preservation of the organisms. As of 2016 over 30 different plant taxa had been described from chert fossils along with a number of fungal species.[58]

Fungi

[edit]| Order | Genus | Species | Authors | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Currah, Stockey, LePage |

An ascomycetan fungus on the host palm Uhlia allenbyensis |

||||

|

Klymiuk |

An ascomycotan fungus |

||||

|

Currah, Stockey, LePage |

An ascomycetan fungus on the host palm Uhlia allenbyensis |

Ferns

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authors | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Karafit et al. |

|||||

|

Stockey, Nishida, & Rothwell |

|||||

|

Smith et al. |

|||||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz, Stockey, & Pigg |

|||||

|

Undescribed[65] |

An osmundaceous fern |

Conifers

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authors | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bassinger |

|||||

|

Stockey |

A 2-needled Pine foliage |

||||

|

Stockey |

A 3-needled Pine foliage |

||||

|

Miller |

A basal Pine |

||||

|

Stockey |

A pinaceous cone |

||||

|

Miller |

A basal Pine |

Angiosperms

[edit]| Family | Genus | Species | Authors | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Erwin & Stockey |

An aquatic or emergent water-plantain |

||||

|

Grímsson, Zetter, & Halbritter |

A Cape-pondweed pollen |

||||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

An arum family member |

||||

|

Erwin & Stockey |

|||||

|

Undescribed[74] |

Cevallos-Ferriz |

A current fruit |

|||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

|||||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A Liriodendron-like wood. |

||||

|

Pigg, Stockey & Maxwell |

A Myrtaceous fruit |

||||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A water lily relative |

||||

|

Stockey, LePage, & Pigg |

A tuplo relative. |

||||

|

Bassinger |

A rose family flower |

||||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A prunoid wood. |

||||

|

"Species 1"[81] |

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A prunoid seed. |

|||

|

"Species 2"[81] |

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A prunoid seed. |

|||

|

"Species 3"[81] |

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A prunoid seed. |

|||

|

Erwin & Stockey |

A possible dodonaecous soapberry family flower |

||||

|

Smith & Stockey |

A lizard's-tail species |

||||

|

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A grape family fruit of uncertain generic placement[85] |

||||

|

incertae sedis |

"Type 1"[84] |

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A grape family fruit of uncertain generic placement |

||

|

incertae sedis |

"Type 2"[84] |

Cevallos-Ferriz & Stockey |

A grape family fruit of uncertain generic placement |

||

|

Zetter & Hesse |

A possible iridaceous pollen morphotype |

||||

|

Robison & Person |

A semi-aquatic dicot of uncertain affinity. |

||||

|

Erwin & Stockey |

A cyperaceous or juncaceous monocot |

||||

|

Stockey |

A possibly aquatic magnoliopsid flower of uncertain affiliation. |

||||

|

Erwin & Stockey |

A lilialean genus of uncertain placement |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Mustoe, G. (2010). "Cyclic sedimentation in the Eocene Allenby Formation of south-central British Columbia and the origin of the Princeton Chert fossil beds". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 48 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1139/e10-085.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj Dillhoff, R.M.; Dillhoff, T.A.; Greenwood, D.R.; DeVore, M.L.; Pigg, K.B. (2013). "The Eocene Thomas Ranch flora, Allenby Formation, Princeton, British Columbia, Canada". Botany. 91 (8): 514–529. doi:10.1139/cjb-2012-0313.

- ^ Greenwood, D.R.; Pigg, K.B.; Basinger, J.F.; DeVore, M.L. (2016). "A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada, and Washington, U.S.A." Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 53 (6): 548–564. Bibcode:2016CaJES..53..548G. doi:10.1139/cjes-2015-0177. hdl:1807/71961.

- ^ a b Archibald, S.; Greenwood, D.; Smith, R.; Mathewes, R.; Basinger, J. (2011). "Great Canadian Lagerstätten 1. Early Eocene Lagerstätten of the Okanagan Highlands (British Columbia and Washington State)". Geoscience Canada. 38 (4): 155–164.

- ^ a b DeVore, M. L.; Nyandwi, A.; Eckardt, W.; Bizuru, E.; Mujawamariya, M.; Pigg, K. B. (2020). "Urticaceae leaves with stinging trichomes were already present in latest early Eocene Okanogan Highlands, British Columbia, Canada". American Journal of Botany. 107 (10): 1449–1456. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1548. PMID 33091153. S2CID 225050834.

- ^ Penhallow, D.P. (1908). "A report on Tertiary plants of British Columbia, collected by Lawrence M. Lambe in 1906 together with a discussion of previously recorded Tertiary floras". Report 1013. Canada Department of Mines, Geological Survey Branch. pp. 1–167.

- ^ Shaw, W. S. (1952). "The Princeton Coalfield, British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada.

- ^ a b c Arnold, C. A. (1955). "A Tertiary Azolla from British Columbia" (PDF). Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. 12 (4): 37–45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grímsson, F.; Grimm, G.; Zetter, R.; Denk, T. (2016). "Cretaceous and Paleogene Fagaceae from North America and Greenland: evidence for a Late Cretaceous split between Fagus and the remaining Fagaceae". Acta Palaeobotanica. 56 (2): 247–305. doi:10.1515/acpa-2016-0016. S2CID 4979967.

- ^ a b Kuc, M. (1972). "Muscites eocenicus sp. nov.—a fossil moss from the Allenby Formation (middle Eocene), British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 9 (5): 600–602. Bibcode:1972CaJES...9..600K. doi:10.1139/e72-049.

- ^ a b c d e f Kuc, M. (1974). "Fossil mosses from the bisaccate zone of the mid-Eocene Allenby Formation, British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 11 (3): 409–421. Bibcode:1974CaJES..11..409K. doi:10.1139/e74-037.

- ^ a b c Dawson, J. W. (1890). On fossil plants from the Similkameen Valley and other places in the southern interior of British Columbia. Royal Society of Canada.

- ^ a b c Miller, N. G. (1980). "Fossil mosses of North America and their significance". The Mosses of North America. pp. 9–36.

- ^ a b Mustoe, G.E. (2002). "Eocene Ginkgo leaf fossils from the Pacific Northwest". Canadian Journal of Botany. 80 (10): 1078–1087. doi:10.1139/b02-097.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnold, C. A. (1955). "Tertiary conifers from the Princeton coal field of British Columbia" (PDF). University of Michigan: Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology. 12: 245–258.

- ^ a b Chaney, R.W. (1951). "A revision of fossil Sequoia and Taxodium in western North America based on the recent discovery of Metasequoia". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 40 (3): 231.

- ^ a b LePage, B. A.; Basinger, J. F. (1995). "Evolutionary history of the genus Pseudolarix Gordon (Pinaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 156 (6): 910–950. doi:10.1086/297313. S2CID 84724593.

- ^ Gooch, N. L. (1992). "Two new species of Pseudolarix Gordon (Pinaceae) from the middle Eocene of the Pacific Northwest". PaleoBios. 14: 13–19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wolfe, J.A.; Wehr, W.C. (1987). Middle Eocene dicotyledonous plants from Republic, northeastern Washington (Report). Bulletin. United States Geological Survey. pp. 1–25. doi:10.3133/b1597. B-1597.

- ^ Pigg, K. B.; Bryan, F. A.; DeVore, M. L. (2018). "Paleoallium billgenseli gen. et sp. nov.: fossil monocot remains from the latest Early Eocene Republic Flora, northeastern Washington State, USA". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 179 (6): 477–486. doi:10.1086/697898. S2CID 91055581.

- ^ Bogner, J.; Johnson, K. R.; Kvacek, Z.; Upchurch, G. R. (2007). "New fossil leaves of Araceae from the Late Cretaceous and Paleogene of western North America" (PDF). Zitteliana. A (47): 133–147. ISSN 1612-412X.

- ^ Pigg, K.B.; Manchester S.R.; Wehr W.C. (2003). "Corylus, Carpinus, and Palaeocarpinus (Betulaceae) from the Middle Eocene Klondike Mountain and Allenby Formations of Northwestern North America". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 164 (5): 807–822. doi:10.1086/376816. S2CID 19802370.

- ^ a b Greenwood, D.R.; Archibald, S.B.; Mathewes, R.W; Moss, P.T. (2005). "Fossil biotas from the Okanagan Highlands, southern British Columbia and northeastern Washington State: climates and ecosystems across an Eocene landscape". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (2): 167–185. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42..167G. doi:10.1139/e04-100.

- ^ Dillhoff, R.M.; Leopold, E.B.; Manchester, S.R. (2005). "The McAbee flora of British Columbia and its relations to the Early-Middle Eocene Okanagan Highlands flora of the Pacific Northwest" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (2): 151–166. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42..151D. doi:10.1139/e04-084.

- ^ DeVore, M. L.; Pigg, K. B. (2007). "A brief review of the fossil history of the family Rosaceae with a focus on the Eocene Okanogan Highlands of eastern Washington State, USA, and British Columbia, Canada". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 266 (1–2): 45–57. Bibcode:2007PSyEv.266...45D. doi:10.1007/s00606-007-0540-3. S2CID 10169419.

- ^ DeVore, M.L.; Moore, S.M.; Pigg, K.B.; Wehr, W.C. (2004). "Fossil Neviusia leaves (Rosaceae: Kerrieae) from the Lower Middle Eocene of Southern British Columbia". Rhodora. 12 (927): 197–209. JSTOR 23314752.

- ^ Wolfe, J.A.; Wehr, W.C. (1988). "Rosaceous Chamaebatiaria-like foliage from the Paleogene of western North America". Aliso. 12 (1): 177–200. doi:10.5642/aliso.19881201.14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wolfe, J.A.; Tanai, T. (1987). "Systematics, Phylogeny, and Distribution of Acer (maples) in the Cenozoic of Western North America". Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University. Series 4, Geology and Mineralogy. 22 (1): 23, 74, 75, 240, & plate 4.

- ^ Manchester, S.; Pigg, K. B.; Kvaček, Z; DeVore, M. L.; Dillhoff, R. M. (2018). "Newly recognized diversity in Trochodendraceae from the Eocene of western North America". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 179 (8): 663–676. doi:10.1086/699282. S2CID 92201595.

- ^ Denk, T.; Dillhoff, R.M. (2005). "Ulmus leaves and fruits from the Early-Middle Eocene of northwestern North America: systematics and implications for character evolution within Ulmaceae". Canadian Journal of Botany. 83 (12): 1663–1681. doi:10.1139/b05-122.

- ^ Wang, Y.; Manchester, S. R. (2000). "Chaneya, a new genus of winged fruit from the Tertiary of North America and eastern Asia". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 161 (1): 167–178. doi:10.1086/314227. PMID 10648207. S2CID 45052368.

- ^ a b c d e f g Russell, L. S. (1957). "Mollusca from the Tertiary of Princeton, British Columbia". National Museum of Canada Bulletin. 147: 84–95.

- ^ a b Douglas, S.; Stockey, R. (1996). "Insect fossils in middle Eocene deposits from British Columbia and Washington State: faunal diversity and geological range extensions". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 74 (6): 1140–1157. doi:10.1139/z96-126.

- ^ a b c Scudder, S. H (1895). "Canadian fossil insects, myriapods and arachnids, Vol II. The Coleoptera hitherto found fossil in Canada". Geological Survey of Canada Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology. 2: 5–26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Scudder, S. H (1879). "Appendix A. The fossil insects collected in 1877, by Mr. G.M. Dawson, in the interior of British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada, Report of Progress for. 1877–1878: 175–185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Rice, H. M. A (1959). "Fossil Bibionidae (Diptera) from British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada Bulletin. 55: 1–36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Handlirsch, A. (1910). "Canadian fossil Insects. 5. Insects from the Tertiary lake deposits of the southern interior of British Columbia, collected by Mr. Lawrence M. Lambe". Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology. 2 (3): 93–129.

- ^ a b Evenhuis (1994). Catalogue of the Fossil Flies of the World (Insecta: Diptera). Backhuys Publishers. pp. 1–600.

- ^ Handlirsch, A. (1909). "Zur Phylogenie und Flügelmorphologie der Ptychopteriden (Dipteren)". Annalen des Kaiserlich-Königlichen Naturhistorischen Hofmuseums. 23: 263–272.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Scudder, S. H (1895). "Canadian fossil insects, myriapods and arachnids, 1. The Tertiary Hemiptera of British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology. 2: 5–26.

- ^ a b Archibald, S.; Mathewes, R.; Aase, A. (2023). "Eocene giant ants, Arctic intercontinental dispersal, and hyperthermals revisited: discovery of fossil Titanomyrma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Formiciinae) in the cool uplands of British Columbia, Canada". The Canadian Entomologist. 155 (e6). doi:10.4039/tce.2022.49. S2CID 256598590.

- ^ Rice, H.M.A. (1968). "Two Tertiary sawflies, (Hymenoptera - Tenthredinidae), from British Columbia". Geological Survey of Canada. 67 (59): 1–21.

- ^ Archibald, S.B. (2005). "New Dinopanorpidae (Insecta: Mecoptera) from the Eocene Okanagan Highlands (British Columbia, Canada and Washington State, USA)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (2): 119–136. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42..119A. doi:10.1139/e04-073.

- ^ Archibald, S. B.; Rasnitsyn, A. P. (2018). "Two new species of fossil Eomerope (Mecoptera: Eomeropidae) from the Ypresian Okanagan Highlands, far-western North America, and Eocene Holarctic dispersal of the genus". The Canadian Entomologist. 150 (3): 393–403. doi:10.4039/tce.2018.13. S2CID 90119028.

- ^ Meunier, F. (1897). "Observations sur quelques insectes du Corallien de la Bavière". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia. 3: 18–23.

- ^ Shcherbakov, D. E. (2006). "The earliest find of Tropiduchidae (Homoptera: Auchenorrhyncha), representing a new tribe, from the Eocene of Green River, USA, with notes on the fossil record of higher Fulgoroidea". Russian Entomological Journal. 15: 315–322.

- ^ a b Archibald, S. B.; Cannings, R. A. (2022). "The first Odonata from the early Eocene Allenby Formation of the Okanagan Highlands, British Columbia, Canada (Anisoptera, Aeshnidae and cf. Cephalozygoptera, Dysagrionidae)". The Canadian Entomologist. 154 (1): e29. doi:10.4039/tce.2022.16. S2CID 250035713.

- ^ Archibald, S. B.; Makarkin, V. N. (2021). "Early Eocene snakeflies (Raphidioptera) of western North America from the Okanagan Highlands and Green River Formation". Zootaxa. 4951 (1): 41–79. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4951.1.2. PMID 33903413. S2CID 233411745.

- ^ Wilson, MVH (1982). "A new species of the fish Amia from the Middle Eocene of British Columbia". Palaeontology. 25 (2): 413–424.

- ^ Mayr, G.; Archibald, S.B.; Kaiser, G.W.; Mathewes, R.W. (2019). "Early Eocene (Ypresian) birds from the Okanagan Highlands, British Columbia (Canada) and Washington State (USA)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 56 (8): 803–813. Bibcode:2019CaJES..56..803M. doi:10.1139/cjes-2018-0267. S2CID 135271937.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, MVH (1977). "Middle Eocene freshwater fishes from British Columbia". Life Sciences Contributions, Royal Ontario Museum. 113: 1–66.

- ^ Wilson, M. V. (1996). "Fishes from Eocene lakes of the interior". In R. Ludvigsen (ed.). Life in stone: a natural history of British Columbia's fossils. Vancouver, BC: The University of British Columbia Press. pp. 212–224.

- ^ Liu, J. (2021). "Redescription of Amyzon'brevipinne and remarks on North American Eocene catostomids (Cypriniformes: Catostomidae)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (9): 677–689. Bibcode:2021JSPal..19..677L. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1968966. S2CID 238241095.

- ^ Russell, L.S. (1935). "A middle Eocene mammal from British Columbia". American Journal of Science. 29 (169): 54–55. Bibcode:1935AmJS...29...54R. doi:10.2475/ajs.s5-29.169.54.

- ^ Eberle, J.J.; Greenwood, D.R. (2017). "An Eocene brontothere and tillodonts (Mammalia) from British Columbia, and their paleoenvironments". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (9): 981–992. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54..981E. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0061. hdl:1807/77901.

- ^ a b Wilson, M. V. (1978). "Eohiodon woodruffi n. sp.(Teleostei, Hiodontidae), from the Middle Eocene Klondike Mountain Formation near Republic, Washington". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 15 (5): 679–686. Bibcode:1978CaJES..15..679W. doi:10.1139/e78-075.

- ^ LePage, B. A.; Currah, R. S.; Stockey, R. A. (1994). "The fossil fungi of the Princeton chert". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 155 (6): 828–836. doi:10.1086/297221. S2CID 85107282.

- ^ Pigg, K. B.; DeVore, M. L. (2016). "A review of the plants of the Princeton chert (Eocene, British Columbia, Canada)". Botany. 94 (9): 661–681. doi:10.1139/cjb-2016-0079. hdl:1807/73571.

- ^ a b Currah, R.S.; Stockey, R.A.; LePage, B.A. (1998). "An Eocene tar spot on a fossil palm and its fungal hyperparasite". Mycologia. 90 (4): 667–673. doi:10.1080/00275514.1998.12026955.

- ^ Klymiuk, A. A. (2016). "Paleomycology of the Princeton Chert. III. Dictyosporic microfungi, Monodictysporites princetonensis gen. et sp. nov., associated with decayed rhizomes of an Eocene semi-aquatic fern". Mycologia. 108 (5): 882–890. doi:10.3852/15-022. PMID 27302048. S2CID 7871220.

- ^ Karafit, S. J.; Rothwell, G. W.; Stockey, R. A.; Nishida, H. (2006). "Evidence for sympodial vascular architecture in a filicalean fern rhizome: Dickwhitea allenbyensis gen. et sp. nov.(Athyriaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 167 (3): 721–727. doi:10.1086/501036. S2CID 85348245.

- ^ Stockey, R. A.; Nishida, H.; Rothwell, G. W. (1999). "Permineralized ferns from the middle Eocene Princeton chert. I. Makotopteris princetonensis gen. et sp. nov.(Athyriaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 160 (5): 1047–1055. doi:10.1086/314191. PMID 10506480. S2CID 33465214.

- ^ Smith, S. Y.; Stockey, R. A.; Nishida, H.; Rothwell, G. W. (2006). "Trawetsia princetonensis gen. et sp. nov.(Blechnaceae): a permineralized fern from the Middle Eocene Princeton Chert". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 167 (3): 711–719. doi:10.1086/501034. S2CID 85160532.

- ^ Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A.; Pigg, K. B. (1991). "The Princeton chert: evidence for in situ aquatic plants". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 70 (1–2): 173–185. Bibcode:1991RPaPa..70..173C. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(91)90085-H.

- ^ Collinson, M. E. (2001). "Cainozoic ferns and their distribution". Brittonia. 53 (2): 173–235. Bibcode:2001Britt..53..173C. doi:10.1007/BF02812700. S2CID 19984401.

- ^ Basinger, J. F. (1981). "The vegetative body of Metasequoia milleri from the Middle Eocene of southern British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Botany. 59 (12): 2379–2410. doi:10.1139/b81-291.

- ^ a b c Stockey, R. A. (1984). "Middle Eocene Pinus remains from British Columbia". Botanical Gazette. 145 (2): 262–274. doi:10.1086/337455. S2CID 85063424.

- ^ a b Miller Jr, C. N. (1973). "Silicified cones and vegetative remains of Pinus from Eocene of British Columbia". Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. 24: 101–118.

- ^ a b Klymiuk, A. A.; Stockey, R. A.; Rothwell, G. W. (2011). "The first organismal concept for an extinct species of Pinaceae: Pinus arnoldii Miller". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 172 (2): 294–313. doi:10.1086/657649. S2CID 84137991.

- ^ Erwin, D. M.; Stockey, R. A. (1991). "Silicified monocotyledons from the Middle Eocene Princeton chert (Allenby Formation) of British Columbia, Canada". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 70 ((1-2)): 147–162. Bibcode:1991RPaPa..70..147E. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(91)90083-F.

- ^ Grímsson, F.; Zetter, R.; Halbritter, H.; Grimm, G. W. (2014). "Aponogeton pollen from the Cretaceous and Paleogene of North America and West Greenland: Implications for the origin and palaeobiogeography of the genus". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 200 (100): 161–187. Bibcode:2014RPaPa.200..161G. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2013.09.005. PMC 4047627. PMID 24926107.

- ^ Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1988). "Permineralized fruits and seeds from the Princeton chert (Middle Eocene) of British Columbia: Araceae". American Journal of Botany. 75 (8): 1099–1113. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1988.tb08822.x.

- ^ Erwin, D.M.; Stockey, R.A. (1994). "Permineralized monocotyledons from the middle Eocene Princeton chert (Allenby Formation) of British Columbia: Arecaceae". Palaeontographica Abteilung B. 234: 19–40.

- ^ Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R. S. (1995). "Fruits of Ribes from the Princeton chert, British Columbia, Canada". American Journal of Botany. 82 (6).

- ^ Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1988). "Permineralized fruits and seeds from the Princeton chert (Middle Eocene) of British Columbia: Lythraceae". Canadian Journal of Botany. 66 (2): 303–312. doi:10.1139/b88-050.

- ^ Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1990). "Vegetative remains of the Magnoliaceae from the Princeton chert (middle Eocene) of British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Botany. 68 (6): 1327–1339. doi:10.1139/b90-169.

- ^ Pigg, K. B.; Stockey, R. A.; Maxwell, S. L. (1993). ""Paleomyrtinaea", a new genus of permineralized myrtaceous fruits and seeds from the Eocene of British Columbia and Paleocene of North Dakota". Canadian Journal of Botany. 71 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1139/b93-001.

- ^ Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1989). "Permineralized fruits and seeds from the Princeton chert (Middle Eocene) of British Columbia: Nymphaeaceae". Botanical Gazette. 150 (2): 207–217. doi:10.1086/337765. S2CID 86651676.

- ^ Stockey, R. A.; LePage, B. A.; Pigg, K. B. (1998). "Permineralized fruits of Diplopanax (Cornaceae, Mastixioideae) from the middle Eocene Princeton chert of British Columbia". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 103 (3–4): 223–234. Bibcode:1998RPaPa.103..223S. doi:10.1016/S0034-6667(98)00038-4.

- ^ Basinger, JF (1976). "Paleorosa similkameenensis, gen. et sp. nov., permineralized flowers (Rosaceae) from the Eocene of British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Botany. 54 (20): 2293–2305. doi:10.1139/b76-246.

- ^ a b c d Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1990). "Vegetative remains of the Rosaceae from the Princeton chert (Middle Eocene) of British Columbia". IAWA Journal. 11 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1163/22941932-90001183. S2CID 85023353.

- ^ Erwin, D. M.; Stockey, R. A. (1990). "Sapindaceous flowers from the Middle Eocene Princeton chert (Allenby Formation) of British Columbia, Canada". Canadian Journal of Botany. 68 (9): 2025–2034. doi:10.1139/b90-265.

- ^ Smith, S. Y.; Stockey, R. A. (2007). "Establishing a fossil record for the perianthless Piperales: Saururus tuckerae sp. nov.(Saururaceae) from the Middle Eocene Princeton Chert". American Journal of Botany. 94 (10): 1642–1657. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.10.1642. PMID 21636361.

- ^ a b c Cevallos-Ferriz, S. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1990). "Permineralized fruits and seeds from the Princeton chert (Middle Eocene) of British Columbia: Vitaceae". Canadian Journal of Botany. 68 (2): 288–295. doi:10.1139/b90-039.

- ^ a b Chen, I.; Manchester, S. R. (2007). "Seed morphology of modern and fossil Ampelocissus (Vitaceae) and implications for phytogeography". American Journal of Botany. 94 (9): 1534–1553. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.9.1534. PMID 21636520.

- ^ Hesse, M.; Zetter, R. (2005). "Ultrastructure and diversity of recent and fossil zona-aperturate pollen grains". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 255 (3): 145–176. Bibcode:2005PSyEv.255..145H. doi:10.1007/s00606-005-0358-9. S2CID 1964359.

- ^ Robison, C. R.; Person, C. P. (1973). "A silicified semiaquatic dicotyledon from the Eocene Allenby Formation of British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Botany. 51 (7): 1373–1377. doi:10.1139/b73-172.

- ^ Erwin, D. M.; Stockey, R. A. (1992). "Vegetative body of a permineralized monocotyledon from the Middle Eocene Princeton chert of British Columbia". Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 147: 309–327.

- ^ Stockey, R. A. (1987). "A permineralized flower from the Middle Eocene of British Columbia". American Journal of Botany. 74 (12): 1878–1887. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1987.tb08790.x.

- ^ Stockey, R. A.; Pigg, K. B. (1991). "Flowers and fruits of Princetonia allenbyensis (Magnoliopsida; family indet.) from the Middle Eocene Princeton chert of British Columbia". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 70 (1–2): 163–172. Bibcode:1991RPaPa..70..163S. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(91)90084-G.

- ^ Erwin, D. M.; Stockey, R. A. (1991). "Soleredera rhizomorpha gen. et sp. nov., a permineralized monocotyledon from the Middle Eocene Princeton chert of British Columbia, Canada". Botanical Gazette. 152 (2): 231–247. doi:10.1086/337885. S2CID 85180086.