Assassination of Ninoy Aquino

| Assassination of Ninoy Aquino | |

|---|---|

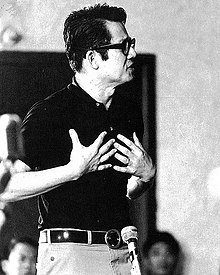

Aquino in 1973 | |

| Location | Manila International Airport, Parañaque, Philippines |

| Date | August 21, 1983 c. 13:00 PST (UTC+08:00) |

| Target | Ninoy Aquino |

Attack type | Shooting |

| Weapons | .45 caliber pistol |

| Deaths | Ninoy Aquino Rolando Galman |

| Assailant | Disputed[1] |

| Accused | Rolando Galman[2] Pablo Martinez[3] Rogelio Moreno |

| Convicted | 16 (including Pablo Martinez and Rogelio Moreno) |

Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr., a former Philippine senator, was assassinated on Sunday, August 21, 1983, on the apron of Manila International Airport (now named Ninoy Aquino International Airport in his honor). A longtime political opponent of President Ferdinand Marcos, Aquino had just landed in his home country after three years of self-imposed exile in the United States when he was shot in the head while being escorted from an aircraft to a vehicle that was waiting to transport him to prison. Also killed was Rolando Galman who was accused of murdering him.

Aquino was elected to the Philippine Senate in 1967 and was critical of Marcos. He was imprisoned on trumped up charges shortly after Marcos's 1972 declaration of martial law. In 1980, he had a heart attack in prison and was allowed to leave the country two months later by Marcos' wife, Imelda. He spent the next three years in exile near Boston before deciding to return to the Philippines.

Aquino's assassination is credited with transforming the opposition to the Marcos regime from a small, isolated movement into a national crusade. It is also credited with thrusting Aquino's widow, Corazon Aquino, into the public spotlight and her running for president in the 1986 snap election. Although Marcos was officially declared the winner of the election, widespread allegations of fraud and illegal tampering on Marcos's behalf are credited with sparking the People Power Revolution, which resulted in Marcos fleeing the country and conceding the presidency to Mrs. Aquino.

Although many, including the Aquino family, maintain that Marcos ordered Aquino's assassination, this was never definitively proven. An official government investigation ordered by Marcos shortly after the assassination led to murder charges against 25 military personnel and one civilian, all of whom were acquitted by the Sandiganbayan (special court). After Marcos was ousted, another government investigation under President Corazon Aquino's administration led to a retrial of 16 military personnel, all of whom were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment by the Sandiganbayan. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision and rejected later motions by the convicted soldiers for a retrial.[1] One of the convicts was subsequently pardoned, three have died in prison, and the remainder had their sentences commuted at various times; the last convicts were released from prison in 2009, the same year Corazon Aquino died.

Background

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Ninoy Aquino began his political career in 1955 first by becoming the mayor of Concepcion, and would go on becoming vice governor of Tarlac in 1959, governor of Tarlac in 1961, and (then the youngest) senator in 1967. During his first years as a senator, Aquino began speaking out against President Ferdinand Marcos. Marcos in turn saw Aquino as the biggest threat to his power.

Aquino was supposed to run for president in the 1973 elections when Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972.[4] On that night, Aquino was imprisoned in Fort Bonifacio, and in 1973, Aquino was falsely charged of murder and subversion.[5] Aquino would first refuse to participate in the military trial citing "injustice", before going on a hunger strike, only for him to go into a coma after 40 days.[6] The trial continued until November 25, 1977, when Aquino was convicted on all charges and was sentenced to death by firing squad.[a][8] However, Aquino and others believed that Marcos would not allow him to be executed as Aquino had gained a great deal of support while imprisoned, and such a fate would surely make him a martyr for his supporters.

In early 1978, Aquino, still in prison, founded a political party named Lakas ng Bayan (or "LABAN")[b] to run for office in the interim Batasang Pambansa elections.[8] During the campaign, Juan Ponce Enrile (then minister of National Defense) accused Ninoy Aquino of having connections with the New People's Army and the CIA, prompting Aquino to appear on a nationally televised interview on March 10, 1978.[9] All LABAN candidates lost to candidates of Marcos' party,[10] amid allegations of election fraud.

On March 19, 1980, Aquino had a heart attack in prison, and in May 1980, he was transported to the Philippine Heart Center where he had a second heart attack. Aquino was diagnosed with angina pectoris and needed triple bypass surgery; however, no surgeon would perform the operation out of fear of controversy, and Aquino refused to undergo the procedure in the Philippines out of fear of sabotage by Marcos, indicating that he would either go to the United States to undergo the procedure or die in his prison cell.[11] First Lady Imelda Marcos arranged for Aquino to undergo surgery at the Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, and he would be released from prison on humanitarian grounds to leave with his family for San Francisco on a Philippine Airlines flight on May 8, 1980.[12] After the surgery, Aquino met with Muslim leaders in Damascus, Syria, before settling with his family in Newton, Massachusetts.

Aquino spent the next three years in self-exile in the U.S., wherein he worked on manuscripts for two books and delivered several lectures and speeches critical of the Marcos government across the nation. As Aquino was to return in 1983 as stipulated in his conditions for his release,[13] Jovito Salonga, then head of the Liberal Party, said about Aquino:

Ninoy was getting impatient in Boston, he felt isolated by the flow of events in the Philippines. In early 1983, Marcos was seriously ailing, the Philippine economy was just as rapidly declining, and insurgency was becoming a serious problem. Ninoy thought that by coming home he might be able to persuade Marcos to restore democracy and somehow revitalize the Liberal Party.[14]

Prelude

[edit]

During an encounter with Imelda Marcos in 1982, Aquino handed her his expiring passport, unaware that she would keep it under her possession.[15] Aquino attempted to submit travel papers at the Philippine Consulate in New York City in June 1983 (only to be rejected under the pretext of a targeted assassination plot)[16] and would end up with two passports – one a blank passport bearing Aquino's real name (via a consulate official) and the other a passport issued in the Middle East under the alias "Marcial Bonifacio" (via former Lanao del Sur congressman Rashid Lucman).[c][17] In July 1983, Pacifico Castro (then Deputy Foreign Minister) warned international air carriers (including JAL) not to allow Aquino to board its planes.[18] Aquino was to return on August 7, but was warned by Juan Ponce Enrile on August 2 to delay his return trip due to alleged "plots against his life".[19]

On August 13, 1983, Aquino, following a morning worship service, went to Boston International Airport, where he would take a flight to Los Angeles[20] to attend conferences with his fellow Filipino contacts. From there, he flew to Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, before heading to Malaysia,[20] where Aquino would meet with Mahathir Mohamad (then the Prime Minister of Malaysia) as well as Indonesian and Thai officials. Aquino would then move back to Singapore, before going to Hong Kong, where he boarded a China Airlines plane bound for Taipei. Once Aquino arrived in Taipei on August 19, he was met by his brother-in-law Ken Kashiwahara, a journalist for ABC News on vacation at that time.[20] On August 20, Aquino was joined by journalists, including Katsu Ueda (Kyodo News), Arthur Kan (Asiaweek), Toshi Matsumoto, Kiyoshi Wakamiya, and news crews from ABC News and Tokyo Broadcasting System,[21] and would later give an interview from his room at the Grand Hotel in which he indicated that he would be wearing a bulletproof vest. He advised the journalists that would be accompanying him on the flight:[22]

You have to be ready with your hand camera because this action can become very fast. In a matter of three or four minutes, it could be all over, and I may not be able to talk to you again after this.

— Ninoy Aquino

On August 21, 1983, Aquino left the Grand Hotel at 9:30 am for Chiang Kai-shek International Airport.[23] Upon arrival at the airport terminal at 10:10 am, Aquino had to spend 20 minutes being driven in circles during baggage check-in to reduce suspicion.[24] After going through immigration via his Marcial Bonifacio passport, Aquino would be stopped by two Taiwanese airport officials, before he (together with Kashiwahara and other members of the press) boarded China Airlines Flight 811, a Boeing 767-200 (registered as B-1836) bound for Manila, and left Taiwan at 11:15 am.[25] In Manila, at least 20,000 opposition supporters arrive at the Manila International Airport via buses and jeeps decorated with yellow ribbons.[26] Aurora Aquino (mother of Ninoy Aquino) and opposition candidates are also present,[26] while a contingent of over 1,000 armed soldiers and police were assigned by the government to provide security for Aquino's arrival. During the flight, Aquino went to the lavatory to put on his bulletproof vest (also the same suit he wore when he left the Philippines for the heart surgery) and handed over a gold watch to Kashiwahara, telling his brother-in law to fetch a bag containing clothes for Aquino's first few days back in prison.[27] His last few moments in the flight while being interviewed by the journalist Jim Laurie, and just prior to disembarking from the flight at Manila airport, were recorded on camera.[28]

Preparations

[edit]On August 19, 1983, then-Assemblyman Salvador Laurel informed Chief of the Philippine Constabulary Gen. Fidel Ramos the arrival of Aquino, requesting "all necessary security measures be undertaken to protect the Senator in view of reported plots against his life." The letter was referred to Chief of Staff Gen. Fabian Ver, who in turn, issued instructions to Aviation Security Command (AVESECOM) Commander Brig. Gen. Luther A. Custodio "to provide necessary security safeguards to protect Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr. while the latter was at the MIA complex."[29]

Under the plan codenamed Oplan Balikbayan, alternative routes were prepared in bringing Aquino from his plane to the SWAT van which was designated to take the senator to Fort Bonifacio:

- Plan ALPHA – Boarding party will escort [Aquino] to exit thru the tube, to the remote holding room to the SWAT van.

- Plan BRAVO – Boarding party will escort [Aquino] to exit thru the bridge stairs to the SWAT van.

Having four (4) implementing plans, the first, Implan Alalay would compose the boarding party. Implan Salubong would then provide security in designated areas in the Manila International Airport complex, Implan Sawata to provide route security, and Implan Masid would conduct intelligence and covert security operations at the MIA.

The “boarding party” that would fetch Sen. Aquino from the plane and ferry him to Fort Bonifacio was initially composed of the following:

- 2Lt Jesus Castro

- Sgt. Arnulfo de Mesa

- Sgt. Claro Lat

- CIC Mario Lazaga

- CIC Rogelio Moreno

Assassination

[edit] B-1836, the incident aircraft, taxiing at Hong Kong's Kai Tak International Airport on October 31, 1983, two months after the assassination. | |

| Incident | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 21, 1983 |

| Summary | Aquino assassinated after landing |

| Site | Manila International Airport, Parañaque, Philippines |

| Total fatalities | 2 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 767-209 |

| Operator | China Airlines |

| Registration | B-1836 |

| Flight origin | Chiang Kai-shek International Airport |

| Destination | Manila International Airport, Parañaque, Philippines |

| Fatalities | 1 |

| Ground casualties | |

| Ground fatalities | 1 |

China Airlines Flight 811 arrived at Manila International Airport at gate number 8 (now gate 11, Terminal 1) at 1:04 pm.[29] When the plane had properly landed, members of the "boarding party," in addition to members of the covert security operations, were already inside the movable tube of the airbridge. Boarding party members de Mesa, Lat, Lazaga, and Castro boarded the airplane to fetch Aquino, while Moreno waited at the doorway of the plane. [30] A member of the covert security operations, Sgt. Filomeno Miranda, was then invited to go inside by the party, while a T/Sgt. Clemente Casta also went inside for some reason."[29]

At 1:14 pm, Aquino rose from seat 14C, and soldiers escorted him off the airplane; instead of going to the terminal, Aquino would, via the jet bridge's service staircase, be taken straight into the tarmac, where a blue AVSECOM van was waiting.[30][29] Just before shots were fired, one person said "Ako na!"[vague] as Aquino went into the service staircase, while another said "Pusila! Pusila! Op! Pusila! Pusila! Pusila!"[d] The audio was recorded on the news camera, but the actual shooting of Aquino was not caught on camera due to the movement and exposure to bright sunlight.[31][32]

Fifty seconds after Aquino rose from his seat,[33] a shot was fired, followed three seconds later by a volley of four shots lasting half a second, and then a second volley of at least twelve shots.[34] When the firing stopped, Aquino and a man later identified as Rolando Galman lay dead on the apron, both from gunshot wounds. Twenty-six M16 shells (5.56 cal), one .45 shell, and five unused bullets (three of them "lead semi-wad cutters" and two "semi-jacket hollow" points) were dropped at the scene of the crime.[35] Aquino's body was carried into an Aviation Security Command (AVSECOM) van by two AVSECOM SWAT soldiers, while another soldier at the bumper of the van continued to fire shots at Galman. The AVSECOM van sped away, leaving behind the bullet-riddled body of Galman. According to news reports[36] (together with a subsequent Sandiganbayan ruling),[37] Aquino had died before arriving at Fort Bonifacio General Hospital; that claim remains controversial due to contradicting evidence presented in court interviews of General Custodio.

Autopsies of both Aquino and Galman were conducted by medical-legal officers Bienvenido O. Muñoz and Nieto M. Salvador at the Loyola Memorial Chapel Morgue and the Philippine Constabulary Crime Laboratory at 10 pm and 11:20 pm, respectively.[38] The Muñoz autopsy showed that Aquino was fatally hit by a bullet "directed forward, downward, and medially" into the head behind his left ear, leaving behind three metal fragments in his head. Bruises were found on Aquino's eyelids, left temple, upper lip, left arm, and left shoulder, while bleeding was found in the forehead and cheek.[39] The Salvador autopsy showed that Galman had died of "shock secondary to gunshot wounds" with eight wounds in his body; the first wound was found behind and above the left ear, second to fourth wounds in the chest, fifth and sixth wound in the back, the seventh wound with nine perforations from stomach to right thigh, and the eighth wound in the elbow region.[40] Seven bullets – four "deformed jacketed", two "slightly deformed jacketed", and one "deformed copper jacket" - were also inside Galman's body.[41]

Initial claims

[edit]Mere hours after the shooting, the government alleged that Rolando Galman was the man who killed Aquino, falsely accusing Galman of being a communist hitman acting on orders from Philippine Communist Party chair Rodolfo Salas.[42][43] During a press conference held at 5:15 pm (four hours after the assassination), Prospero Olivas (then the chief of the Philippine Constabulary Metropolitan Command) claimed that the assailant in "his twenties, dressed in blue pants and white shirt"[e] shot Aquino in the back of the head from behind with a .357 magnum revolver;[36] however, Olivas excluded from his accounts chemistry report C-83-1136, which showed that fragments extracted from Aquino were from a .38 caliber or .45 caliber pistol.[44]

A military reenactment aired on August 27, 1983, featuring many of the AVSECOM officials actually involved in the assassination.[45] The reenactment showed that as Aquino (flanked by three officers) descended down the 19-step stairs of the jetway for 9.5 seconds, the assailant emerged from the back of the stairs and fired at Aquino.[46] Several members of the security detail in turn fired a single volley at Galman, killing him.[47] Olivas later admitted that the reenactment had "some inaccuracies, such as the wrong type of plane and the absence of several people at the scene of the murder," and hinted of a potential "second" and more accurate reenactment.[48] An official report of the Marcos government and Pablo Martinez stated that Galman shot Aquino dead. However, there is no solid evidence to substantiate this claim.[31]

Investigation

[edit]Everyone from the Central Intelligence Agency, to the United Nations, to the Communist Party of the Philippines, to First Lady Imelda Marcos were accused of conspiracy.[better source needed][49] President Marcos was reportedly gravely ill, recovering from a kidney transplant when the incident occurred. Theories arose as to who was in charge and who ordered the execution. Some hypothesized that Marcos had a long-standing order for Aquino's murder upon the latter's return.

Agrava Board

[edit]On August 24, 1983, Marcos created a fact-finding board called the Fernando Commission (after the head of the commission and then-Supreme Court Chief Justice Enrique Fernando) to investigate Aquino's assassination.[50] Four retired Supreme Court justices aged 68 to 80 were also appointed;[50] they resigned after its composition was challenged in court. Arturo M. Tolentino declined his appointment as board chair. However, the commission held only two sittings due to intense public criticism.[29]

On October 14, 1983, President Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 1886,[51] creating an independent board of inquiry, called the "Agrava Commission" or "Agrava Board". The board was composed of former Court of Appeals Justice Corazon Agrava[29] as chair, with lawyer Luciano E. Salazar, entrepreneur Dante G. Santos, labor leader Ernesto F. Herrera, and educator Amado C. Dizon as members.

The Agrava Fact-Finding Board convened on November 3, 1983. Before the Agrava Board could start its work, President Marcos claimed that the decision to eliminate Aquino was made by the general-secretary of the Philippine Communist Party, Rodolfo Salas. He was referring to his earlier claim that Aquino had befriended and subsequently betrayed his communist comrades.

The Agrava Board conducted public hearings and requested testimonies from several persons who might shed light on the crimes, including Imelda Marcos, and General Fabian Ver, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

In the subsequent proceedings, no one actually identified who fired the gun that killed Aquino, but Rebecca Quijano, another passenger, testified that she saw a man behind Aquino (running from the stairs towards Aquino and his escorts) point a gun at the back of his head, after which there was a sound of a gunshot. A post-mortem analysis disclosed that Aquino was shot in the back of the head at close range with the bullet exiting at the chin at a downward angle, which supported Quijano's testimony. More suspicions were aroused when Quijano described the assassin as wearing a military uniform. Some airside employees of the airport on duty during the assassination gave testimonies that support that of Quijano, stating that Galman was having a conversation with one soldier when gunshots rang out.

After a year of thorough investigation – with 20,000 pages of testimony given by 193 witnesses, the Agrava Board submitted two reports to President Marcos – the Majority and Minority Reports. The Minority Report, submitted by Chairman Agrava alone, was submitted on October 23, 1984. It confirmed that the Aquino assassination was a military conspiracy, but it cleared General Ver. Many believed that President Marcos intimidated and pressured the members of the Board to persuade them not to indict Ver, Marcos's first cousin and most trusted general. Excluding Chairman Agrava, the majority of the board submitted a separate report – the Majority Report indicting several members of the Armed Forces including Ver, General Luther Custodio, head of the AVSECOM, and General Prospero Olivas, chief of the Metropolitan Command (METROCOM). The board members unanimously rejected the theory that it was Galman who killed Aquino.[52] The Agrava Board forwarded its findings to the Ombudsman for trial by the Sandiganbayan.[52]

Funeral

[edit]Even though Aquino was embalmed by renowned embalmer Frank Malabed, Aquino's mother Aurora instructed the embalmer not to apply makeup on the body,[53] so that the public may see "what they did to my son."[54] His remains lay in state for eight days. However, Aquino's family decided to display Aquino with the blood-stained safari jacket he wore upon his assassination, and refused any makeup to disguise the visible wounds in his face. Thousands of supporters flocked to Aquino's wake, which took place at his house on Times Street in West Triangle, Quezon City. During this time, his remains was also brought to Santo Domingo Church. Aquino's wife, Corazon, and children Ballsy, Pinky, Viel, Noynoy, and Kris arrived from Boston the day after the assassination. In a later interview, Aquino's eldest daughter, Ballsy (now Aquino-Cruz), recounted that they learnt of the assassination through a phone call from Kyodo News.[55] She was initially shocked upon being asked to confirm if her father had indeed been killed. The report of the assassination was verified to Aquino's family when Shintaro Ishihara, an acquaintance of Ninoy and a member of the Japanese Parliament, called Cory and informed her that Kiyoshi Wakamiya, a journalist who had been with Ninoy in the flight from Taipei to Manila, confirmed the shooting to him.[56]

Aquino's remains were later brought to Tarlac for a funeral in Concepcion and at the Hacienda Luisita Chapel.[57][58] Those were later returned to Santo Domingo Church, where his funeral was held on August 31. Following a Mass at 9 am, with the Cardinal Archbishop of Manila, Jaime Sin officiating, the funeral procession brought his remains to Manila Memorial Park in Parañaque. The flatbed truck that served as his hearse wound through Metro Manila for 12 hours. It passed by Rizal Park, where the Philippine flag had been brought to half-staff. Aquino's casket finally reached the memorial park at around 9 pm. More than two million people lined the streets for the procession. Some stations like the church-run Radio Veritas and DZRH were the only stations to cover the entire ceremony.[59]

National Day of Sorrow massacre

[edit]A month after Aquino's assassination, Cory Aquino organized a "National Day of Sorrow" rally in Manila on September 21, 1983, to both commemorate the declaration of martial law and to continue the mourning of Ninoy Aquino's death. As the rally was about to end, a group of breakaway protesters in the thousands went to the Mendiola Bridge (now the Don Chino Roces Bridge) where marines and firemen were stationed, initiating a standoff that resulted in the deaths of 11 people, seven of whom were protesters.[60][61]

Trials and convictions

[edit]In 1985, 25 military personnel (including several generals and colonels) and one civilian were charged for the murders of Benigno Aquino Jr. and Rolando Galman. President Marcos relieved Ver as AFP Chief and appointed his second cousin, General Fidel V. Ramos, as acting AFP Chief. The accused were tried by the Sandiganbayan (special court). After a brief trial, the Sandiganbayan acquitted all of the accused on December 2, 1985.[62] Immediately after the decision, Marcos reinstated Ver. The 1985 Sandiganbayan ruling and the reinstatement of Ver were denounced as a mockery of justice.

After Marcos was ousted in 1986, another investigation was set up by the new government.[63] The Supreme Court ruled that the previous court proceedings were "a sham" ordered by the "authoritarian president" himself; the Supreme Court ordered a new Sandiganbayan trial.[64][65] Sixteen defendants were found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment by the Sandiganbayan in 1990[66] and ordered to pay damages to the families of Aquino and Galman.[67][68]

The sixteen were Brig. Gen. Luther Custodio, Capt. Romeo Bautista, 2nd Lt. Jesus Castro, Sergeants Claro L. Lat, Arnulfo de Mesa, Filomeno Miranda, Rolando de Guzman, Ernesto Mateo, Rodolfo Desolong, Ruben Aquino, and Arnulfo Artates, Constable Rogelio Moreno (the gunman),[69] M/Sgt. Pablo Martinez (also the alleged gunman), C1C Mario Lazaga, A1C Cordova Estelo, and A1C Felizardo Taran. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision in 1991.[66]

Pablo Martinez, one of the convicted conspirators in the assassination, alleged that his co-conspirators told him that Danding Cojuangco ordered the assassination. Martinez also alleged that only he and Galman knew of the assassination, and that Galman was the actual shooter, a point not corroborated by other evidence in the case.[70] The convicts filed an appeal to have their sentences reduced after 22 years, claiming that the assassination was ordered by Marcos's crony and business partner (and Corazon Aquino's estranged cousin) Danding Cojuangco. The Supreme Court ruled that it did not qualify as newly found evidence. Even though the Supreme Court did not convict Ferdinand Marcos, there are those that still believe that he did, indeed, kill Ninoy Aquino.[71] Through the years, some have been pardoned, others have died in detention, while others have had their terms commuted and then served out. In November 2007, Pablo Martinez was released from the New Bilibid Prison after President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo ordered his release on humanitarian grounds.[72] In March 2009, the last remaining convicts were released from prison.

Aftermath

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

Aquino's death transformed the Philippine opposition from a small isolated movement to a massive unified crusade, incorporating people from all walks of life. The middle class got involved, the impoverished majority participated, and business leaders whom Marcos had irked during martial law endorsed the campaign – all with the crucial support of the military and the Catholic Church hierarchy. The assassination showed the increasing incapacity of the Marcos regime – Ferdinand was mortally ill when the crime occurred while his cronies mismanaged the country in his absence. It outraged Aquino's supporters that Marcos, if not masterminding it, allowed the assassination to happen and engineered its cover-up. The mass revolt caused by Aquino's demise attracted worldwide media attention and Marcos's American contacts, as well as the Reagan administration, began distancing themselves. There was a global media spotlight on the Philippine crisis, and exposes on Imelda's extravagant lifestyle (most infamously, her thousands of pairs of shoes) and "mining operations", as well as Ferdinand's excesses, came into focus.

The assassination thrust Aquino's widow, Corazon, into the public eye. She was the presidential candidate of UNIDO opposition party in the 1986 snap election, running against Marcos. The official results showed a Marcos victory, but this was universally dismissed as fraudulent.[73][74] In the subsequent People Power Revolution, Marcos resigned and went into exile, and Corazon Aquino became president.

While no Filipino president has ever been assassinated, Benigno Aquino is one of three presidential spouses who had been murdered. Alicia Syquia-Quirino and three of her children were murdered by Imperial Japanese troops along during the Battle of Manila in 1945, while Doña Aurora Quezon was killed along with her daughter and son-in-law in a Hukbalahap ambush in 1949.

AVSECOM van discovery

[edit]In 2010, the AVSECOM van that bore Aquino's body was found in Villamor Air Base in Pasay in a decrepit state.[75] It had been apparently dumped in a secluded area of the base where it was left to rot until its purchase by Marlon Marasigan, a retired Philippine Air Force colonel in 1997.[76]

The van was brought to the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) complex in 2019 for restoration. The van will be displayed at the Freedom Memorial Museum, located at the University of the Philippines Diliman campus, when the museum is completed. A scale replica of the China Airlines aircraft as well as the original airbridge where Ninoy alighted will also be added to the exhibit. A proposal to display the van at the Presidential Car Museum in Quezon City was deemed inappropriate by NHCP chair Rene Escalante.[77]

Memorials

[edit]

In 1987, Manila International Airport, where the assassination occurred, was renamed "Ninoy Aquino International Airport". The spot on the apron where his body lay sprawled is now marked by a brass plaque.

August 21 was declared Ninoy Aquino Day, a national holiday, through the passage of Republic Act No. 9256.[78] Under then-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the observance of this holiday became moveable – to be celebrated on the "Monday nearest August 21" every year – as part of her controversial 'holiday economics' philosophy as reflected in Republic Act No. 9492.[79] The commemoration has since been reverted to August 21 by orders of former President Benigno Aquino III.

Fate of aircraft

[edit]The Boeing 767 involved in the incident continued its service with China Airlines until 1989 when it was sold to Air New Zealand and re-registered as ZK-NBF upon the Taiwanese carrier's delivery of Boeing 747-400 aircraft. It then went to fly for Air Canada as C-FVNM until its withdrawal in 2008. The plane was then stored in Roswell for twelve more years until its eventual scrapping in 2020.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]- The incident is dramatized at the beginning of the 1988 political thriller film A Dangerous Life, starring Gary Busey. The Agrava Board is also depicted in the film and the depiction of the incident is based on the testimony of one of the few witnesses to the assassination, Rebecca Quijano, as well as airport employees who also witnessed the shooting.

- An archival audio of the incident is heard in the 2002 film, Dekada 70.

- The incident is dramatized in the March 26, 2009, episode of the GMA Network docudrama series, Case Unclosed, named "Sino ang Pumatay kay Ninoy?" ("Who Killed Ninoy?").

- The incident is mentioned in the 2012 Filipino science fiction horror anthology film Shake, Rattle and Roll Fourteen: The Invasion through radio news reports during the ending of the segment "Pamana" ("Inheritance").

- The 2023 film Martyr or Murderer explores the assassination of Ninoy Aquino on August 21, 1983, three years before the events of Maid in Malacañang, and how the Marcoses were accused of being responsible for the assassination.[80]

- The 2013 musical Here Lies Love depicts the assassination in the song "Gate 37" (the title refers to the gate Aquino departed from at Logan International Airport).

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Ministry of Justice would later invalidate Aquino's death sentence as "moot and academic" upon his departure from the Philippines. However, President Marcos would reaffirm such death sentence on July 31, 1983.[7]

- ^ Lakas ng Bayan is a Tagalog term for "people's force", with the backronym laban meaning "fight" in Tagalog.

- ^ The first name Marcial refers to martial law, and the last name Bonifacio alludes to Fort Bonifacio, where Ninoy was imprisoned.

- ^ Pusila is an imperative form of the Cebuano word pusil (based on the Spanish word fusil). In this context, Pusila! is translated as "Shoot (him)!"

- ^ Contrary to Olivas, Galman, the alleged person, was wearing a light blue shirt.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Who masterminded Ninoy's murder?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

Who masterminded Ninoy's murder? After 35 years and after two Aquino presidencies, the answer remains a legal enigma.

- ^ "Who killed Ninoy? (1)". Philippine Daily Inquirer. August 16, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ "Bandila: One of the accused on killing Ninoy dies". ABS-CBN News. YouTube.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 5 and 7.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 8.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, pp. 43 and 61; Hill & Hill 1983, p. 16.

- ^ a b Hill & Hill 1983, p. 10.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 11.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 13.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 15.

- ^ "The Greatest President We Never Had". Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, p. 43; Hill & Hill 1983, p. 16.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, p. 43; Hill & Hill 1983, p. 17.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, p. 61; Aquino 2003, p. A18.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Hill & Hill 1983, p. 25.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 26, 53.

- ^ "Ninoy Aquino: Worth Dying For (the last interview!)". Youtube.com. September 16, 2008. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Kashiwahara 1983, p. 41.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, p. 41; Hill & Hill 1983, p. 26.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, pp. 41–42; Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Hill & Hill 1983, p. 27.

- ^ Kashiwahara 1983, p. 41; Hill & Hill 1983, p. 28.

- ^ Laurie, Jim (June 30, 2010). "The Last moments and assassination of Ninoy Aquino". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Sandiganbayan ruling – Investigation of the assassination of Benigno Aquino (PDF). Maynila: Fact Finding Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Hill & Hill 1983, p. 28.

- ^ a b "Agosto Beinte-Uno". ABS-CBN News. August 29, 2018. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Benigno Aquino Assassinated – 1983 | Today In History | Aug 21, 17". AP Archive. YouTube.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 32 and 35–36.

- ^ a b Hill & Hill 1983, p. 31.

- ^ People of the Philippines v. B/Gen. Luther A. Custodio, et al., 1983, Decision of the Special Division of the Sandiganbayan in Criminal Case No. 10010 and 10011

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 33 and 94–97.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 33–34 and 98.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 34.

- ^ Chronicles of a Revolution: 1995, p. 27

- ^ "G.R. No. 72670 – Saturnina Galman vs. Sandiganbayan". Chan Roble Virtual Law Library. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ del Mundo, Larah Vinda (August 21, 2022). "How Marcos suppressed the truth behind Ninoy Aquino's assassination". Vera Files. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 39.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, pp. 39–40, 43.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 40.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 43.

- ^ "6 People Who Killed Ninoy Aquino, According to Conspiracy Theorist". August 21, 2014. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Hill & Hill 1983, p. 36.

- ^ Presidential Decree No. 1886 (1983), Creating a Fact-Finding Board with Plenary Powers to Investigate the Tragedy Which Occurred on August 21, 1983, retrieved August 30, 2013

- ^ a b del Mundo, Larah Vinda (August 21, 2022). "How Marcos suppressed the truth behind Ninoy Aquino's assassination". Vera Files. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ Hill & Hill 1983, p. 35.

- ^ "Francisco Malabed, mortician to Marcos and Ninoy, dies at 67". ABS-CBN News. September 22, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "The assassination of Benigno Aquino". History Channel. May 6, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ "24 hours that changed Philippine history." Philippine Daily Inquirer, August 21, 2013. Accessed August 28, 2021. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/470559/24-hours-that-changed-philippine-history.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (August 28, 1983). "CROWDS MOB AQUINO HEARSE; CARDINAL REJECTS INQUIRY ROLE". New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Cojuangco, Tingting (August 23, 2009). "Memories from August 1983". The Philippine Star. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Robles, Raissa (August 25, 2014). "Ninoy's funeral was the day Filipinos stopped being afraid of dictators". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Bonabente, Cyril L. (January 22, 2007). "Did you know". Philippine Daily Inquirer. The Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc. p. A22. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Mercado, Monina Allarey; Tatad, Francisco S.; Reuter, James B. (1986). People Power: An Eyewitness History. James B. Reuter, S.J., Foundation. p. 314. ISBN 978-0863161315.

- ^ 10 things of interest about the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, Aquino, Tricia. (August 20, 2013), Interaksyon.com

- ^ "Challenge to Marcos: The Tumult Since '83; Aquino Assassination in 1983 Created Conditions for Crisis". The New York Times. February 23, 1986. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ Panganiban, Artemio (August 26, 2018). "Who masterminded Ninoy's murder?". Inquirer. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ Yamsuan, Cathy Cañares (August 22, 2021). "Agrava report on Ninoy Aquino slay: Groundbreaking search for truth". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "In the Know: Pablo Martinez among 16 soldiers convicted of killing Aquino". Inquirer. May 9, 2014. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "Philippine Court Convicts 16, Acquits 20 in Slaying of Aquino's Husband". Los Angeles Times. September 28, 1990. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "Cold Trail: 10 Issues and Cases in the Philippines That are Still Unresolved". Spot. January 20, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Gavilan, Jodesz (August 20, 2016). "Look back: The Aquino assassination". RAPPLER. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "Transcript of ABS-CBN Interview with Pablo Martinez, co-accused in the Aquino murder case". Archived from the original on June 28, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Custodio vs Sandiganbayan : 96027-28 : March 8, 2005 : J. Puno : En Banc Resolution". sc.judiciary.gov.ph. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ "Aquino-Galman murder convict freed by Arroyo". GMA News. November 22, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ "Fact Check: Controversial Lawyer Claimed Marcos Sr. Won The 1986 Snap Elections". Rappler. June 13, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Flake, Dennis Edward (February 23, 2021). "Reflections on the 1986 Snap Election and the People Power Revolution". Inquirer USA. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Robles, Raissa. (August 20, 2012). "Ninoy Aquino's death van". Inside Philippine Politics and Beyond.

- ^ Cayabyab, Jason. (August 22, 2019). [1]. Van that carried Ninoy's body up for restoration.

- ^ "Museum is final stop of Avsecom van that bore Ninoy's body". August 22, 2019.

- ^ Republic Act No. 9256 (2004), Act Declaring August 21 of Every Year as Ninoy Aquino Day, a Special Nonworking Holiday, and for Other Purposes, retrieved April 28, 2011

- ^ Republic Act No. 9492 (2007), Act Rationalizing the Celebration of National Holidays Amending for the Purpose Section 26, Chapter 7, Book I of Executive Order No. 292, as amended, otherwise known as the Administrative Code of 1987, retrieved April 28, 2011

- ^ "Darryl Yap reveals main cast of 'Martyr Or Murderer'". Stephanie Bernardino. Manila Bulletin. November 25, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Hill, Gerald N.; Hill, Kathleen Thompson (1983). Aquino Assassination: The True Story and Analysis of the Assassination of Philippine Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. Steve Psinakis. Sonoma, Calif.: Hilltop Pub. Co. ISBN 0-912133-04-X.

News articles

[edit]- Aquino, Corazon C. (August 21, 2003). "The last time I saw Ninoy". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Vol. 18, no. 254. pp. A1 and A18.

- Kashiwahara, Ken (October 16, 1983). "Aquino's Final Journey". The New York Times. Vol. CXXXIII, no. 45833. pp. 41–43, 61–62, 64–66, and 69. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

External links

[edit]- I AM NINOY website* History Channel's feature documentary on Ninoy Aquino's Assassination on YouTube

- "'The last time I saw Ninoy' - Aug. 21, 2003". Archived from the original on May 16, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Time (magazine)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120114150414/http://www.rmaf.org.ph/Awardees/Biography/BiographyAquinoCor.htm

- The good die young: Sen. Benigno Servillano Aquino Jr. (1932-1983). Index to Philippine Periodicals

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120930105738/http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/20080821-155890/Fewer-than-10-people-in-plot-5-core-5-others-in-the-know

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120930105809/http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/20080823-156342/The-Pattugalan-Memos-on-Project-Four-Flowers

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090808024519/http://services.inquirer.net/print/print.php?article_id=154970

- Tambayan ng mga Benignian

- Video on YouTube

- Assassinations in the Philippines

- Deaths by person in the Philippines

- 1983 in the Philippines

- Filmed assassinations

- History of Metro Manila

- People Power Revolution

- Political repression in the Philippines

- Presidency of Ferdinand Marcos

- August 1983 events in Asia

- Conspiracy theories in the Philippines

- 1983 murders in the Philippines

- Death and funerary practices in the Philippines