Religion in pre-colonial Philippines

This article possibly contains original research. (June 2019) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Philippines portal |

Religions in pre-colonial Philippines included a variety of faiths, of which the dominant faiths were polytheist indigenous religions practiced by the more than one hundred distinct ethnic groups in the archipelago. Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam were also present in some parts of the islands. Many of the traditions and belief systems from pre-colonial Filipino religions continue to be practiced today through the Indigenous Philippine folk religions, Folk Catholicism, Folk Hinduism, among others.

The original faith of the people of the Philippines were the Indigenous Philippine folk religions. Belief systems within these distinct polytheist-animist religions were later influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. With the arrival of Islam in the 14th century, the older religions slowly became less dominant in some small portions in the southwest. European colonial ambitions tried to influence the people through Christian ideologies via Catholicism in the 16th century. Despite the attacks initiated by Abrahamic faiths against the Philippine indigenous folk religions by way of colonization and its after-effects, many of the indigenous religious traditions survived, while many were also infused into Abrahamic religions in the form of Folk Catholicism and Folk Islam.

The earliest archaeological findings believed to have religious significance are the Angono Petroglyphs, which are mostly symbolic representations and are associated with healing and sympathetic practices from the Indigenous Philippine folk religions,[1] of which the earliest examples are believed to have been used earlier than 2000 BC., during the Philippines' Neolithic age.[2] The earliest written evidence comes from the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, dated to around 900 CE, which uses the Buddhist–Hindu lunar calendar.

Indigenous Philippine folk religions

[edit]

Indigenous Philippine folk religions, which older references classified as animist in orientation, were the primary form of religious belief practiced in the prehistoric and early historic Philippines before the arrival of foreign influences. Today, only a handful of the indigenous tribes continue to practice the old traditions. The term animism encompasses a collection of beliefs and cultural mores anchored more or less in the idea that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities, both good and bad, and that respect must be accorded to them through worship. These nature spirits later became known as "diwatas", despite keeping most of their native meanings and symbols, due to the influence of Hinduism in the region.

Some worship specific deities, such as the Tagalog supreme deity, Bathala, and his children Adlaw, Mayari, and Tala, or the Visayan deity Kan-Laon. These practices coincided with ancestor worship. Tagalogs for example venerated animals like the crocodile (buaya) and often called them "nonong" (from cognate 'nuno' i.e. 'ancestor' or 'elder'). A common ancient curse among the Tagalogs is "makain ka ng buwaya" "may the crocodile eat you!" Animistic practices vary between different ethnic groups. Magic, chants and prayers are often key features. Its practitioners were highly respected (and sometimes feared) in the community, as they were healers (Mananambal), midwives (hilot), shamans, witches and warlocks (mangkukulam), tribal historians and wizened elders that provided the spiritual and traditional life of the community.

In the Visayan regions, shamanistic and animistic beliefs in witchcraft and mythical creatures like aswang (vampires), duwende (dwarves), and bakonawa (a gigantic sea serpent) Similarly to Naga, may exist in some indigenous peoples alongside more mainstream Christian and Islamic faiths.

Anito

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: the usage of terminology here is no longer reflected in the way they are used in current scholarship. (July 2023) |

Anito is a collective name for the pre-Hispanic belief system in the Philippines. It is also used to refer to spirits, including the household deities, deceased ancestors, nature-spirits, nymphs and diwatas (minor gods and demi-gods). Ancient Filipinos kept statues to represent these spirits, ask guidance and protection. Elders, ancestors and the environment were all highly respected. Although Anito survives to the present day, it has for the most part been Christianized and incorporated into Folk Catholicism.

Folk healers

[edit]During the pre-Hispanic period, babaylan were shamans and spiritual leaders and mananambal were medicine men. At the onset of the colonial era, the suppression of the babaylans and the native Filipino religion gave rise to the albularyo. By exchanging the native prayers and spells with Catholic oraciones and Christian prayers, the albularyo was able to syncretize the ancient mode of healing with the new religion.

Revitalization attempts

[edit]In search of a national culture and identity, away from those imposed by Spain during the colonial age, Filipino revolutionaries during the Philippine Revolution proposed to revive the indigenous Philippine folk religions and make them the national religion of the entire country. However, due to the war against the Spanish and, later, American colonizers, focus on the revival of the indigenous religions were sidelined to make way for war preparations against occupiers.[3]

Buddhism

[edit]

Although no written record exists about early Buddhism in the Philippines, recent archaeological discoveries and a few scant references in the other nations' historical records can testify that Buddhism was present from the 9th century. These records mention the independent states that comprised the Philippine archipelago, rather one united country as the Philippines are organized today.

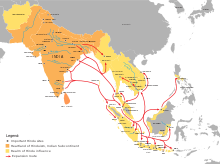

Early Philippine states became tributary states of the powerful Buddhist Srivijaya empire that controlled trade in Maritime Southeast Asia from the 6th to the 13th centuries. The states' trade contacts with the empire either before or during the 9th century served as a conduit to introduce Vajrayana Buddhism to the Philippines.

In 1225, China's Zhao Rugua, a superintendent of maritime trade in Fukien province wrote the book entitled Zhu Fan Zhi (Chinese: 諸番志; lit. 'Account of the Various Barbarians') in which he described trade with a country called Ma-i on the island of Mindoro in Luzon. In it he said:

The country of Mai is to the north of Borneo. The natives live in large villages on the opposite banks of a stream and cover themselves with a cloth like a sheet or hide their bodies with a loin cloth. There are metal images of Buddhas of unknown origin scattered about in the tangled wilds.[5]

In the 12th century, Malay immigrants arrived in Palawan, where most settlements came to be ruled by Malay chieftains. They were followed by the Indonesians of the Majapahit Empire in the 13th century, and they brought with them Buddhism.

Surviving Buddhist images and sculptures are primarily found in and at Tabon Cave.[6] Recent research conducted by Philip Maise has included the discovery of giant sculptures, has also discovered what he believes to be cave paintings within the burial chambers in the caves depicting the Journey to the West.[7]

The Chinese annal Song Shih recorded the first appearance of a tributary mission from Butuan (Li Yui-han 李竾罕 and Jiaminan) at the Chinese Imperial Court on March 17, 1001 AD. It described Butuan as a small maritime Hindu country with a Buddhist monarchy that had regular contact with Champa and intermittent contact with China under the Rajah named Kiling.[8]

The Ancient Batangueños were influenced by India as shown in the origin of most languages from Sanskrit and certain ancient potteries. A Buddhist image was reproduced in mould on a clay medallion in bas-relief from the municipality of Calatagan. According to experts, the image in the pot strongly resembles the iconographic portrayal of Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal. The pot shows Buddha Amithaba in the tribhanga[9] pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars also noted that there is a strong Mahayanic orientation in the image, since the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was also depicted.[10]

Lunar observations

[edit]- Subang – new moon

- Gimat/ungut – full crescent

- Hitaas na an subang – high new moon (3rd day)

- Balining – the 4th or 5th night

- Odto na anbalan – quarter moon

- Dayaw/paghipono/takdul/ugsan – full moon

- Madulumdulum – waning moon

- Banolor – night or 2 later of waning, set on western horizon just before dawn

- Parik – 5th or 6th night of waning

- Katin – 3rd quarter so it crossed the 2nd barrier by the 24th or 25th night

- Malasumbang – 29th night; getting ready for the new moon

Hinduism

[edit]

The archipelagoes of Southeast Asia were under the influence of Hindu Tamil, Gujarati and Indonesian traders through the ports of Malay-Indonesian islands. Indian religions, possibly an syncretic version of Hindu-Buddhism, arrived in the Philippine archipelago in the 1st millennium AD and lasted through the first half of the second millennium AD, through the Indonesian kingdom of Srivijaya followed by Majapahit. Archeological evidence suggesting exchange of ancient spiritual ideas from India to the Philippines includes the 1.79 kilogram, 21 carat golden image of Agusan (sometimes referred to as Golden Tara), found in Mindanao in 1917 after a storm and flood exposed its location.[11] The statue now sits in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and is dated from the period 13th to early 14th centuries.

Before the Spanish colonization of the archipelago, it was estimated that up to a third of Filipinos had Hindu beliefs, or prayed to and worshipped a Hindu god. [12]

A study of this image was made by Dr. F. D. K. Bosch, of Batavia, in 1920, who came to the conclusion that it was made by local workmen in Mindanao, copying a Ngandjuk image of the early Madjapahit period – except that the local artist overlooked the distinguishing attributes held in the hand. It probably had some connection with the Javanese miners who are known to have been mining gold in the Agusan-Surigao area in the middle or late 14th century. The image is apparently that of a Sivaite goddess, and fits in well with the name "Butuan" (signifying "phallus").

— H. Otley Beyer, 1947[13]

Juan Francisco suggests that the golden Agusan statue may be a representation of goddess Sakti of the Siva-Buddha (Bhairava) tradition found in Java, in which the religious aspect of Shiva is integrated with those found in Buddhism of Java and Sumatra.[14]

Folklore, arts and literature

[edit]Most fables and stories in Philippine culture are linked to Indian arts, such as the story of monkey and the turtle, the race between the deer and the snail (similar to the Western story of The Tortoise and the Hare), and the hawk and the hen. Similarly, the major epics and folk literature of the Philippines show common themes, plots, climax and ideas expressed in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.[15]

According to Indologists Juan R. Francisco and Josephine Acosta Pasricha, Hindu influences and folklore was firmly established in Philippines when the surviving inscriptions of about 9th to 10th century AD were discovered.[16] The Maranao version is the Maharadia Lawana (King Rāvaṇa of Hindu Epic Ramayana). Lam-Ang is the Ilocano version and Sarimanok (akin to the Indian Garuda) is the legendary bird of the Maranao people. In addition, many verses from the Hud-Hud of the Ifugao are derived from the Indian Hindu epics Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[17]

Buddhist-Hindu influences

[edit]The Darangen or Singkil epic of the Maranao people hearten back to this era as the most complete local version of the Ramayana. Maguindanao at this time was also strongly Hindu, evidenced by the Ladya Lawana (Rajah Ravana) epic saga that survived to the modern day, as albeit highly Islamized from the 17th century onwards.

Tigmamanukan

[edit]The Tigmamanukan was a blue and black bird (believed to be the Philippine Fairy Bluebird) which served as a messenger of Bathalang Maykapal, in which it was also an omen.[18] If one encountered a Tigmamanukan while traveling, they should take note of the direction of its flight. If the bird flew to the right, the traveler would not encounter any danger during their journey. If it flew to the left, the traveler would never find their way and would be lost forever.

Islam

[edit]

The Muslim Bruneian Empire, under the rule of Sultan Bolkiah (who is an ancestor of the current Sultan of Brunei, Hassanal Bolkiah), subjugated the Kingdom of Tondo in 1500. Afterwards, an alliance was formed between the newly established Kingdom of Maynila (Selurong) and the Sultanate of Brunei and the Muslim Rajah Sulaiman was installed in power. Furthermore, Sultan Bolkiah's victory over Sulu and Seludong (modern day Manila),[19] as well as his marriages to Laila Mecanai, the daughter of Sulu Sultan Amir Ul-Ombra (an uncle of Sharifa Mahandun married to Nakhoda Angging or Maharaja Anddin of Sulu), and to the daughter of Datu Kemin, widened Brunei's influence in the Philippines.[20]

Rajah Suleyman and Rajah Matanda in the south (now the Intramuros district) were installed as Muslim kings and the Buddhist-Hindu settlement was under Raja Lakandula in northern Tundun (now Tondo.)[21] Islamization of Luzon began in the sixteenth century when traders from Brunei settled in the Manila area and married locals while maintaining kinship and trade links with Brunei and thus other Muslim centres in Southeast Asia. There is no evidence that Islam had become a major political or religious force in the region, with Father Diego de Herrera recording that inhabitants in some villages were Muslim in name only.[22]

Historiographic sources

[edit]Early foreign written records

[edit]Most records concerning pre-colonial Philippine religion can be traced back through various written accounts from Chinese, Indian and Spanish sources.

- The Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI)

- Zhu Fan Zhi (Chinese: 諸番志; lit. 'Account of the Various Barbarians')

- Boxer Codex- Spanish written accounts

LCI

[edit]The Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI) is the most significant archaeological discovery in the Philippines because it serves as the first written record of the Philippine nation. The LCI mentions a debt pardon for a person, Namwaran, and his descendants by the Rajah of Tundun (now Tondo, Manila) on the fourth day after Vaisakha, in the Saka year 822, which has been estimated to correspond to April 21, 900 CE. The LCI uses the old Buddhist-Hindu lunar calendar.

Antoon Postma, an anthropologist and an expert in ancient Javanese literature, has deciphered the LCI and he says it records a combination of old Kavi, Old Tagalog, and Sanskrit.[23]

Ancient artifacts

[edit]The Philippines's archaeological finds include many ancient gold artifacts.[24][25] Most of them have been dated to belong to the 9th century.

The artifacts reflect the iconography of the Vajrayana Buddhism and its influences on the Philippines's early states.[26]

Some of the iconography and artifacts are exampled

- Lingling-o The artifacts' distinct features point to their production in the islands. It is probable that they were made locally because archaeologist Peter Bellwood discovered the existence of an ancient goldsmith's shop that made the 20-centuries-old lingling-o, or omega-shaped gold ornaments in Batanes.

- Copper Buddhas of Ma-i (metal relics) – "The gentleness of Tagalog customs that the first Spaniards found, very different from those of other provinces of the same race and in Luzon itself, can very well be the effect of Buddhism. "There are copper Buddha's" images.[27] the people in Ma-i sound like newcomers [to this port] since they don't know where those metal statues in the jungle come from."[5]

- Bronze Lokesvara – This is bronze statue of Lokesvara was found in Isla Puting Bato in Tondo, Manila.[10]

- Buddha Amithaba bass relief The Ancient Batangueños were influenced by India as shown in the origin of most languages from Sanskrit and certain ancient potteries. A Buddhist image was reproduced in mould on a clay medallion in bas-relief from the municipality of Calatagan. According to experts, the image in the pot strongly resembles the iconographic portrayal of Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal. The pot shows Buddha Amithaba in the tribhanga[9] pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars also noted that there is a strong Mahayanic orientation in the image, since the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was also depicted.[28]

- Golden Garuda of Palawan- The other finds are the garuda, the mythical bird that is common to Buddhism and Hinduism, Another gold artifact, from the Tabon Caves in the island of Palawan, is an image of Garuda, the bird who is the mount of Vishnu. The discovery of sophisticated Hindu imagery and gold artifacts in Tabon Caves has been linked to those found from Oc Eo, in the Mekong Delta in Southern Vietnam.

- Bronze Ganesha statues – A crude bronze statue of a Hindu Deity Ganesha has been found by Beyer in 1921 in an ancient site in Puerto Princesa, Palawan and in Mactan. Cebu the crude bronze statue indicates of its local reproduction.[10]

- Mactan Alokitesvara – Excavated in 1921 in Mactan, Cebu by Beyer, the bronze statue may be a siva-buddhist blending rather than "pure Buddhist".[10]

- The Golden Tara was discovered in 1918 in Esperanza, Agusan by Bilay Campos a Manobo tribeswoman.[29] The Golden Tara was eventually brought to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois in 1922. Beyer and other experts have agreed on its identity and have dated it to belong within 900–950 CE. They cannot place, however, its provenance because it has distinct features.[30]

- Golden Kinnari- The golden-vessel kinnari was found in 1981 in Surigao. The kinnari exists in both Buddhist and Hindu mythology. In Buddhism, the kinnari, a half-human and half-bird creature, represents enlightened action. The Buddhist Lotus Sutra mentions the kinnari as the celestial musician in the Himavanta realm. The kinnari takes the form of a centaur, however, in India's epic poem, the Mahabharata, and in the Veda's Purana part.

- Padmapani and Nandi images – Padmapani is also known as Avalokitesvara, the wisdom being or Bodhisattva of Compassion. Golden jewelry found so far include rings, some surmounted by images of Nandi – the sacred bull, linked chains, inscribed gold sheets, gold plaques decorated with repoussé images of Hindu deities.[31]

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription In 1989, a laborer working in a sand mine at the mouth of Lumbang River near Laguna de Bay found a copper plate in Barangay Wawa, Lumban. This discovery, is now known as the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by scholars. It is the earliest known written document found in the Philippines, dated to be from the 9th century AD, and was deciphered in 1992 by Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma. The copperplate inscription suggests economic and cultural links between the Tagalog people of Philippines with the Javanese Medang Kingdom, the Srivijaya empire, and the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of India. This is an active area of research as little is known about the scale and depth of Philippine history from the 1st millennium and before.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Angono Petroglyphs". UNESCO. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Jalandoni, Andrea; Taçon, Paul S.C. (2018). "A new recording and interpretation of the rock art of Angono, Rizal, Philippines". Rock Art Research. 35 (1): 47–61.

- ^ Kenno, L. W. V. (1901). The Katipunan of the Philippines. The North American Review.

- ^ Acri, Andrea (December 20, 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Scott 1984, p. 68.

- ^ Camperspoint: History of Palawan Archived January 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed August 27, 2008.

- ^ "'Great Sphinx' Found in Tabon Caves in Palawan". MetroCebu. August 12, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "Timeline of history". Archived from the original on November 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "Tribhanga". Archived from the original on January 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Churchill 1977.

- ^ Golden Tara Government of the Philippines

- ^ "Golden Tara".

- ^ Beyer 1947.

- ^ Francisco 1963b.

- ^ Halili 2010, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Mellie Leandicho Lopez (2008), A Handbook of Philippine Folklore, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-9715425148, pp xxiv–xxv

- ^ Manuel, E. Arsenio (1963), A Survey of Philippine Folk Epics, Asian Folklore Studies, 22, pp 1–76

- ^ Scott 1994.

- ^ Saunders 2013, p. 41.

- ^ "Brunei". CIA World Factbook. 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Teodoro Agoncillo, History of the Filipino People, p 22

- ^ A. Newson, Linda (2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. UP Hawaii. ISBN 9780824832728.

- ^ Antoon Postma, "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription," Philippines Studies, 1992 40: 183–203.

- ^ Jesus T. Peralta, "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments CB Philippines," Arts of Asia, 1981, 4:54–60.

- ^ Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors' in Newsweek.

- ^ Laszlo Legeza, "Tantric Elements in the Philippines PreHispanic Gold Arts," Arts of Asia, 1988, 4:129–136.

- ^ Rizal, Jose (2000). Political and Historical Writings (Vol. 7). Manila: National Historical Institute.

- ^ Francisco 1963.

- ^ Agusan Gold Image only in the Philippines.

- ^ Agusan Image Documents, Agusan-Surigao Historical Archives.

- ^ Bennett 2009.

Sources

[edit]- Bennett, Anna T N (2009). "Gold in early Southeast Asia". ArchéoSciences. 33 (33): 99–107. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.2072.

- Beyer, H Otley (1947). "Outline Review of Philippine Archaeology by Islands and Provinces" (PDF). Philippine Journal of Science. 77 (34). Bureau of Printing: 205–374.

- Churchill, Malcolm H (1977). "Indian Penetration of pre-Spanish Philippines: A new look at the evidence" (PDF). 15. Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman: 21–45.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dang, V T; Vu, Q H (1977). "Excavation at Giong Ca Vo site". Journal of Southeast Asian Archaeology. 17: 30–37.

- Francisco, Juan R (1963). "A Buddhist Image from Karitunan Site, Calatagan, Batangas Province" (PDF). Asian Studies. 1. Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman: 13–22.

- Francisco, Juan (1963b). "A Note on the Golden Image of Agusan". Philippine Studies. 11 (3). Ateneo de Manila University: 390–400.

- Halili, Maria (2010). Philippine History. Rex. ISBN 978-9712356360.

- Saunders, Graham E (2013). History for Brunei. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136874086.

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials: for the study of Philippine History. New Day. ISBN 978-9711002268.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. UP Hawai'i. ISBN 978-9715501354.