Afrin Canton

| Afrin Canton Kantona Efrînê/مقاطعة عفرين | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One of the two cantons of the Afrin Region | |||||||||

| 2017–2018 | |||||||||

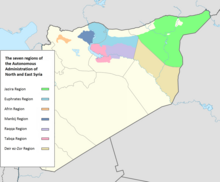

Afrin Canton was part of the Afrin Region (orange) | |||||||||

| Capital | Afrin[1] | ||||||||

| Historical era | Syrian Civil War | ||||||||

• Formation of the Afrin Region (then "Afrin Canton") | 2014 | ||||||||

• Reorganisation of the Administrative divisions of Rojava | 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Afrin Canton (Kurdish: Kantona Efrînê; Arabic: مقاطعة عفرين; Classical Syriac: ܦܠܩܐ ܕܥܦܪܝܢ, romanized: Pelqā dha-ʻAfrin) was one of the cantons of Rojava. Syria's Afrin District fell under the control of the People's Protection Units (YPG) around 2012 and an "Afrin Canton" (now Afrin Region) was declared in 2014. Afrin Canton in its latest form was established in 2017, however, as part of the reorganisation of Rojava's subdivisions. With Afrin as its administrative centre,[2] the canton was part of the larger Afrin Region. As a result of Operation Olive Branch in early 2018, Afrin Canton became part of the Turkish occupation of northern Syria. The government of the Afrin Region now administers only the area around Tell Rifaat.[3][4]

Demographics

[edit]The population of the Afrin Canton area was overwhelmingly ethnic Kurdish, to the degree that the canton had been described as "homogeneously Kurdish".[5] The overall population of Afrin Canton, based on the 2004 Syrian census, was about 200,000.[6]

Cities and towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants according to the 2004 Syrian census are Afrin (36,562) and Jindires (13,661).

Throughout the course of the Syrian Civil War, Afrin Canton served as a safe haven for refugees of all ethnicities, fleeing violence and destruction from civil war factions, in particular the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the diverse more or less Islamist rebel groups of the Syrian opposition.[7][8] According to a June 2016 estimate from the International Middle East Peace Research Center, about 316,000 displaced Syrians of Kurdish, Yazidi, Arab and Turkmen ethnicity lived in Afrin Canton at the time.[9]

History

[edit]According to René Dussaud, the area of Kurd-Dagh and the plain near Antioch were settled by Kurds since antiquity.[10][11] According to Kurdish scholar Ismet Cheriff Vanly, there is reason to believe that Kurdish settlements in the Kurd Mountains go back to the Seleucid Empire, since those regions stood in the path to Antioch; Kurds in the early periods served as mercenaries and mounted archers.[12] In any case, the Kurd Mountains were already Kurdish-inhabited when the Crusades broke out at the end of the 11th century.[13]

The area around Afrin developed as the center of a distinctive Sufi "Kurdish Islam".[14] In modern post-independence Syria, the Kurdish society of the canton was subject to heavy-handed Arabization policies by the Damascus government.[15]

In the course of the Syrian civil war, Damascus government forces pulled back from the canton in spring 2012 to give way to the People's Protection Units (YPG) and autonomous self-government under the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, which was formally declared on 29 January 2014.[16] Until 2018, violence in Afrin was minor, involving artillery shelling by Jabhat al-Nusra[17] as well as by Turkey.[18][16][19]

Afrin Canton was captured by the Turkish Land Forces and Syrian National Army (SNA) as result of the 2018 Afrin offensive. Tens of thousands of Kurdish refugees fled from Afrin City before its capture by the SNA in March 2018,[20][21] and the YPG vowed to retake it. The YPG subsequently announced its intention to start a guerrilla war in Afrin Canton,[22][23] leading to the SDF insurgency in Northern Aleppo.

Economy

[edit]

A diverse agricultural production was at the heart of the Afrin Canton's economy,[24] traditionally olives in particular, and more recently there was a focus on increasing wheat production.[25] A well-known product from the area is Aleppo soap, a hard soap made from olive oil and lye, distinguished by the inclusion of laurel oil. While Afrin Canton has been the source of olive oil for Aleppo soap since antiquity, the destruction caused by the Syrian Civil War to other parts of Aleppo governorate increasingly made the entire production chains locate in Afrin Canton.[26][27] At the height of the fighting for Aleppo, up to 50 percent of the city's industrial production was moved to Afrin Canton.[28] As of early 2016, two million pairs of jeans were produced per month and exported across Syria.[28] In January 2017, 400 textile industry workshops counted 17,000 employees, supplying the whole of Syria.[29]

Afrin Canton was under a blockade imposed by neighbouring Turkey,[30] which placed high burdens on international import and export. For example, transportation of Aleppo soap to international markets, as far as possible at all, had at least four times the transportation cost as compared to pre-war years.[31] In 2015 there were 32 tons of Aleppo soap produced and exported to other parts of Syria, but also to international markets.[28]

Tourism

[edit]Afrin District also served as a center for domestic tourism due to its beautiful landscapes. Syrians continued to travel to the region for recreational purposes after the formation of Afrin Region, and later Afrin Canton. The tourism was however somewhat constricted due to the YPG's tight control of the borders, and the war; local tourism mostly collapsed during the Turkish invasion of 2018.[32]

Education

[edit]Like in the other Rojava cantons, primary education in the public schools is initially by mother tongue instruction either Kurdish or Arabic, with the aim of bilingualism in Kurdish and Arabic in secondary schooling.[33][34] Curricula are a topic of continuous debate between the canton' Boards of Education and the Syrian central government in Damascus, which partly pays the teachers.[35][36][37]

The federal, regional and local administrations in Rojava put much emphasis on promoting libraries and educational centers, to facilitate learning and social and artistic activities.[38]

Afrin Canton had an institution of higher education, the University of Afrin, founded in 2015. After teaching three programs (Electromechanical Engineering, Kurdish Literature and Economy) in the first academic year, the second academic year with an increased 22 professors and 250 students has three additional programs (Human Medicine, Journalism and Agricultural Engineering).[39] The university was closed after the Turkish invasion; its students were able to follow up on their studies at the Rojava University in Qamishli.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Walid Al Nofal; Tariq Adely (12 March 2018). "Turkish-backed rebels poised to encircle Afrin city after days of swift advances". Syria Direct. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons; Personal Website of Mutlu Civiroglu". civiroglu.net. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "YPG start retreating from Afrin city center after they abandoned and burned their headquarters in the city". syria.liveuamap.com. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Turkey's forces capture Syrian Kurdish town of Afrin". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Rojava's Sustainability and the YPG's Regional Strategy". Washington Institute. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Serious allegations against the Turkish government". Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ "1,150 emigrants enter Afrin canton". Hawar News Agency. 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Will Afrin be the next Kobani?". Al-Monitor. 9 June 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ Dussaud, René (1927). Topographie historique de la Syrie antique et médiévale. Geuthner. pp. 425.

- ^ Chaliand, Gérard (1993). A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan. Zed Books. p. 196. ISBN 9781856491945.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (2005). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-134-90766-3.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (2005). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-134-90766-3.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi; Welle, Jane (2009). Syria's kurds history, politics and society (PDF) (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- ^ "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996.

- ^ a b Thomas Schmidinger (24 February 2016). "Afrin and the Race for the Azaz Corridor". Newsdeeply. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Nusra militants shell Kurdish areas in Syria's Afrin, Kurds respond". ARA News. 30 August 2015. Archived from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Turkish forces shell Afrin countryside, killing and injuring about 16 most of them from the self-defense forces and Asayish". SOHR. 9 July 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Turkey strikes Kurdish city of Afrin northern Syria, civilian casualties reported". ARA News. 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Kurds locked out of Afrin as Ghouta refugees take their place".

- ^ "'Nothing is ours anymore': Kurds forced out of Afrin after Turkish assault". TheGuardian.com. 7 June 2018.

- ^ Al Jazeera (16 March 2018). "Syrian civilians flee embattled Eastern Ghouta and Afrin". Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera Media Network. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "11 killed in bomb blast as Syria's Afrin falls to pro-Turkish forces". Middle East Eye. 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ "Afrin is building its economy on agriculture". Hawar News Agency. 8 August 2016. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ "Agriculture Commission is Looking at the Process of Receiving Wheat from Farmers". Afrin Canton. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "Famous Aleppo soap victim of Syria's conflict". YourMiddleEast. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". Al-Monitor. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ a b c "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". Al-Monitor. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ "Rojava: The Economic Branches in Detail". cooperativeeconomy.info. 14 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Rojava'dan ikazlar". Cumhuriyet.

- ^ "Bio-Seife aus dem Kriegsgebiet". Der Spiegel. 13 February 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Khaled al-Khateb (26 July 2018). "Day trippers flock to Afrin's orchards as Aleppo restores security". al-Monitor. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ "Education in Rojava after the revolution". ANF. 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Hassakeh: Syriac Language to Be Taught in PYD-controlled Schools". The Syrian Observer. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ "Revolutionary Education in Rojava". New Compass. 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Kurds introduce own curriculum at schools of Rojava". Ara News. 2015-10-02. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability". Kurdistan24. 2016-07-07. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ^ "Afrin University is opened today". Hawar News Agency. 9 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ "Afrin University students continuing their studies at Rojava's University - ANHA | HAWARNEWS | English". www.hawarnews.com. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

External links

[edit]- Map of majority ethnicities in Syria by Gulf2000 project of Columbia University