2004 Qamishli riots

| 2004 Qamishli riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 12 March 2004[1] | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Clashes between rival football fans | ||

| Resulted in | Massacre by the Syrian Army

| ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 30+ | ||

| Injuries | 100+ | ||

| Arrested | 2,000+ | ||

The 2004 Qamishli riots were an uprising by Syrian Kurds in the northeastern city of Qamishli in March 2004, which culminated in a massacre by the Syrian Arab Armed Forces.

Relations between the Arabs who settled in Qamishli during the Arab Belt programme and Kurdish inhabitants had been tense for decades. In March 2004, clashes broke out between Arab and Kurdish audiences during a chaotic football match. The Ba'ath Party local office was burned down by Kurdish demonstrators, who went on to destroy the statue of Hafez al-Assad in Qamishli city, echoing the toppling of Firdos Square statue in 2003.[4][5]

The Syrian military swiftly responded; deploying troops backed by tanks and helicopters, and launching an extensive crack-down. At least 30 Kurds were killed and 160 wounded as the security forces re-asserted control over the city.[6][7] As a result of the crackdown, thousands of Syrian Kurds fled to Iraqi Kurdistan.

Background

[edit]Qamishli is the largest town in Al-Hasakah Governorate and is located in northeast Syria. It is regarded as the Kurdish and Assyrian community capital. It is also the center of the Syrian Kurdish struggle,[8] especially in the recent years.

The Kurds also felt opposition from the Syrian government in 1962, forty years before, when the government took census and left out of it many Kurds. This left them and their children without citizenship and the right to obtain government jobs or to have property. This disregarded minority now consists of hundreds of thousands of Kurds, who carry identification cards as "foreigner". Another move the government made which has fueled tensions was resettling Arabs from other parts of the country into along the border in Iran, Iraq and Turkey. They did this in order to build a buffer between Kurdish areas, which has furthered the hatred between the Kurds and Arabs.[9] During the 1970s, thousands of Arabs from the city of Raqqa were settled along a 180-mile strip of Kurdish-majority regions, after confiscating lands from the Kurdish inhabitants in the region, as part of the Ba'athist Arab Belt project. Relations between the Arab settlers and Kurds in the region remained tense for decades.[10]

The United States has for a longer period of time recognized Iraqi Kurdistan diplomatically which has led the Americans to invite the current Kurdish leader of Iraqi Kurdistan, Masoud Barzani, to the White House and a meeting in Baghdad when the American president was in town. The visit from United States Vice President, Joe Biden, to the fourth largest city in Iraq, Erbil, also known as the Iraqi Kurdistan capital, helped strengthen their alliance with them.[11] The United States started Operation Provide Comfort and Operation Provide Comfort II in an attempt to defend Kurds fleeing their homes in Northern Iraq as a result of the Iraqi Gulf War. Kurdish representation in Iraqi government has increased since the American invasion in 2003. Jalal Talabani, the first Kurdish president of Iraq, was elected in 2005, and Kurds have held the presidential seat since, although the position is somewhat ornamental.[12][13]

2004 events

[edit]

On 12 March 2004, a football match in Qamishli between a local Kurdish team and an Arab team from Deir ez-Zor in Syria's southeast sparked violent clashes between fans of the opposing sides which spilled into the streets of the city. The fans of the Arab team reportedly rode about town in a bus, insulting the Iraqi Kurdish leaders Masoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani, then leaders of Iraqi Kurdistan's two main parties. In response, Kurdish fans supposedly proclaimed "We will sacrifice our lives for Bush", referring to US President George W. Bush, who invaded Iraq in 2003, deposing Saddam and triggering the Iraq War. Tensions between the groups came to a head, and the Deir ez-Zor Arab fans attacked the Kurdish fans with sticks, stones, and knives. Government security forces brought in to quell the riot, fired into the crowd, killing six people, including three children—all of them were Kurds.[14]

The Ba'ath Party local office was burned down by the demonstrators, leading to the security forces responding and killing more than 15 of the rioters and wounding more than 100.[15] Officials in Qamishli alleged that some Kurdish parties were collaborating with "foreign forces" to supposedly annex some villages in the area to northern Iraq.[16][17][18] Events climaxed when Kurds in Qamishli toppled a statue of Hafez al-Assad. The Syrian army responded quickly, deploying thousands of troops backed by tanks and helicopters. At least 30 Kurds were killed as the security services re-took the city, over 2,000 were arrested at that time or subsequently.[6]

Prosecution of the Kurdish protestors

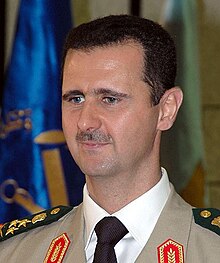

[edit]After the violence, President Bashar al-Assad visited the region aiming to achieve a "national unity" and supposedly pardoned 312 Kurds who were prosecuted of participating in the massacre.[9]

Aftermath

[edit] |

|---|

|

|

Moqebleh (Moquoble) refugee camp

[edit]After the 2004 events in Qamishli, thousands of Kurds fled to the Kurdish Region of Iraq.[19] Local authorities there, the UNHCR and other UN agencies established the Moqebleh camp at a former Army base near Dohuk.

Several years later the KRG moved all refugees, who arrived before 2005, to housing in a second camp, known as Qamishli. The camp consists of a modest housing development with dozens of concrete block houses and a mosque.

The original camp at the former Army citadel now contains about 300 people. Many of the homes are made of cement blocks, covered with plastic tarpaulins. Latrines and showers are in separate buildings down the street. Authorities provide electricity, water trucks and food rations.[20]

Syrian Kurds can leave the camp to work. As supposed refugees they cannot get government jobs, but are able work in the private sector, often as construction workers or drivers. The Syrian Kurds seem likely not to return to Syria until political conditions change.

2005 demonstrations

[edit]In June 2005, thousands of Kurds demonstrated in Qamishli to protest the assassination of Sheikh Khaznawi, a Kurdish cleric in Syria, resulting in the death of one policeman and injury to four Kurds.[21][22] In March 2008, according to Human Rights Watch,[23] Syrian security forces opened fire at Kurds who were celebrating the spring festival of Nowruz. The shooting killed three people.

2008 vigil in memory of the riots

[edit]On 21 March 2008, the Kurdish New Year (Newroz) a school class held a 5 minute vigil in memory of the 2004 Qamishli riots. The participants were investigated for holding the vigil.[24]

2011 protests in Qamishli

[edit]With the eruption of the Syrian Civil War, the city of Qamishli became one of the protest arenas. On 12 March 2011, thousands of Syrian Kurds in Qamishli and al-Hasakah protested on the day of the Kurdish martyr, an annual event since 2004 al-Qamishli protests.[25][26][27]

2012 rebellion

[edit]Armed rebellions were supported by Mashouq al-Khaznawi. In 2012, armed elements among the Kurds launched Syrian Kurdish rebellion in north and north-western Syria, aiming against Syrian government forces.[28][29] In the second half of 2012, the rebellion also resulted in clashes between Kurdish soldiers and the militants of the Free Syrian Army, both striving towards control of the region. The AANES would later gain control over most of northern Syria.

See also

[edit]- Assyrians in Syria

- First Iraqi–Kurdish War

- Human rights in Syria

- Kurdish–Turkish conflict

- Kurds in Syria

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- Serhildan

References

[edit]- ^ "Syria: Prisoners of Conscience in Damascus Central Prison declare hunger strike". marxist.com. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Arab tribal fighters declare war on Kurdish YPG forces, north Syria". 20 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "March 12th Uprising is a historical turn towards freedom | ANHA". en.hawarnews.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ James Brandon (15 February 2007). "The PKK and Syria's Kurds". Terrorism Monitor. Vol. 5, no. 3. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008.

- ^ Ahmed, Akbar (2013). "4: Musharraf's Dilemma". The Thistle and the Drone. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8157-2378-3.

- ^ a b James Brandon (15 February 2007). "The PKK and Syria's Kurds". Terrorism Monitor. Vol. 5, no. 3. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008.

- ^ Ahmed, Akbar (2013). "4: Musharraf's Dilemma". The Thistle and the Drone. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8157-2378-3.

- ^ Qantara.de - The Kurds of Syria - An Insecure Stone in the Syrian Mosaic

- ^ a b Fattah, Hassan M. (2 July 2005). "Kurds, Emboldened by Lebanon, Rise Up in Tense Syria (Published 2005)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Ahmed, Akbar (2013). "4: Musharraf's Dilemma". The Thistle and the Drone. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8157-2378-3.

- ^ Osman, Hiwa. "US Relations With Iraqi Kurdistan". Rudaw. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ Unknown. "Jalal Talabani". Kurish Aspect. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ "Iraq Report: December 8, 2000". Radio Free Europe. 8 December 2000.

- ^ Tejel, p. 115

- ^ "Football fans' fight causes a three-day riot in Syria". Independent.co.uk. 17 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022.

- ^ Aji, Albert; (Associated Press) (16 March 2004). "Tension unabated after riots in Syria". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Turning Points 2014". Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Syria: Address Grievances Underlying Kurdish Unrest, HRW, 19 March 2004.

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Reese Erlich, "Syrian Kurds have long memories," Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, 21 October 2011. http://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/syria-kurds-moqebleh-refugee-camp-oppose-assad-regime Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blanford, Nicholas (15 June 2005). "A murder stirs Kurds in Syria". USA Today.

- ^ Fattah, Hassan M. (2 July 2005). "Kurds, Emboldened by Lebanon, Rise Up in Tense Syria". The New York Times.

- ^ "Syria: Investigate Killing of Kurds". 24 March 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ "Group Denial". Human Rights Watch. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Youtube. "مظاهرة في الجزيرة السورية 12 اذار 2011". Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Youtube. "حفلة تأبين شهداء إنتفاضة قامشلو". Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ soparo.com. "الكورد السوريون يحييون ذكرى انتفاضتهم السابعة بايقاد الشموع اجلالاً و اكراماُ لارواح الشهداء". Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "Kurdish Syria: From cultural to armed revolution". 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Hedging their Syrian bets". The Economist. 4 August 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Tejel, Jordi (2009). "The Qamishli revolt, 2004: the marker of a new era for Kurds in Syria". Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London: Routledge. pp. 108–132. ISBN 9780415424400.

- Qamishli

- Riots and civil disorder in Syria

- History of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

- Massacres in 2004

- 2004 riots

- Association football hooliganism

- Persecution of Kurds in Syria

- Kurdish rebellions in Syria

- Kurdish protests

- March 2004 events in Asia

- Democratic Union Party (Syria)

- 2004 crimes in Syria

- Massacres of Kurds

- 21st-century mass murder in Syria

- Massacres of protesters in Asia

- Massacres committed by Syria

- Arson in Syria

- 2004 fires in Asia

- Arson in 2004

- 2004 protests

- Reactions to the Iraq War

- Crime in al-Hasakah Governorate