African Americans

Proportion of Black Americans in each U.S. county, as of the 2020 U.S. census | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Alone (one race): In combination (mixed race): Alone or in combination: | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Predominantly the Southern United States and American urban centers, including: | |

| 3,552,997[1] | |

| 3,320,513[1] | |

| 3,246,381[1] | |

| 2,986,172[1] | |

| 2,237,044[1] | |

| Languages | |

| American English (incl. African-American English and African-American Vernacular English) | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Christianity (78%)[note 1] Other:[2] Irreligion (18%) Islam (2%) See: Religion of Black Americans | |

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African Americans or Black Americans, formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial or ethnic group consisting of people who self-identity as having origins from Sub-Saharan Africa. They constitute the country's second largest racial group after White Americans.[3] The primary understanding of the term "African American" denotes a community of people descended from enslaved Africans, who were brought over during the colonial era of the United States.[4][5] As such, it typically does not refer to Americans who have partial or full origins in any of the North African ethnic groups, as they are instead broadly understood to be Arab or Middle Eastern, although they were historically classified as White in United States census data.

While African Americans are a distinct group in their own right,[6][7] some post-slavery Black African immigrants or their children may also come to identify with the community, but this is not very common; the majority of first-generation Black African immigrants identify directly with the defined diaspora community of their country of origin.[8][9] Most African Americans have origins in West Africa and coastal Central Africa, with varying amounts of ancestry coming from Western European Americans and Native Americans, owing to the three groups' centuries-long history of contact and interaction.[10]

African-American history began in the 16th century, with West Africans and coastal Central Africans being sold to European slave traders and then transported across the Atlantic Ocean to the Western Hemisphere, where they were sold as slaves to European colonists and put to work on plantations, particularly in the Southern colonies. A few were able to achieve freedom through manumission or by escaping, after which they founded independent communities before and during the American Revolution. When the United States was established as an independent country, most Black people continued to be enslaved, primarily in the American South. It was not until the end of the American Civil War in 1865 that approximately four million enslaved people were liberated, owing to the Thirteenth Amendment.[11] During the subsequent Reconstruction era, they were officially recognized as American citizens via the Fourteenth Amendment, while the Fifteenth Amendment granted adult Black males the right to vote; however, due to the widespread policy and ideology of White American supremacy, Black Americans were largely treated as second-class citizens and soon found themselves disenfranchised in the South. These circumstances gradually changed due to their significant contributions to United States military history, substantial levels of migration out of the South, the elimination of legal racial segregation, and the onset of the civil rights movement. Nevertheless, despite the existence of legal equality in the 21st century, racism against African Americans and racial socio-economic disparity remain among the major communal issues afflicting American society.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, immigration has played an increasingly significant role in the African-American community. As of 2022[update], 10% of Black Americans were immigrants, and 20% were either immigrants or the children of immigrants.[12] In 2009, Barack Obama became the first African-American president of the United States.[13] In 2020, Kamala Harris became the country's first African-American vice president.

The African-American community has had a significant influence on many cultures globally, making numerous contributions to visual arts, literature, the English language (African-American Vernacular English), philosophy, politics, cuisine, sports, and music and dance. The contribution of African Americans to popular music is, in fact, so profound that most American music—including jazz, gospel, blues, rock and roll, funk, disco, house, techno, hip hop, R&B, trap, and soul—has its origins, either partially or entirely, in the community's musical developments.[14][15]

History

Colonial era

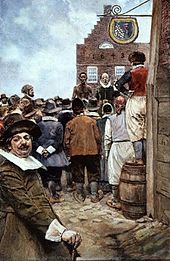

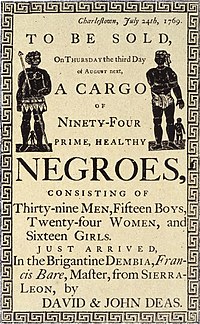

The vast majority of those who were enslaved and transported in the transatlantic slave trade were people from several Central and West Africa ethnic groups. They had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids,[16] or sold by other West Africans, or by half-European "merchant princes"[17] to European slave traders, who brought them to the Americas.[18]

The first African slaves arrived via Santo Domingo in the Caribbean to the San Miguel de Gualdape colony (most likely located in the Winyah Bay area of present-day South Carolina), founded by Spanish explorer Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón in 1526.[19] The ill-fated colony was almost immediately disrupted by a fight over leadership, during which the slaves revolted and fled the colony to seek refuge among local Native Americans. De Ayllón and many of the colonists died shortly afterward, due to an epidemic and the colony was abandoned. The settlers and the slaves who had not escaped returned to the Island of Hispaniola, whence they had come.[19]

The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free Black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a White Segovian conquistador in 1565 in St. Augustine (Spanish Florida), is the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in what is now the continental United States.[20]

The first recorded Africans in English America (including most of the future United States) were "20 and odd negroes" who arrived in Jamestown, Virginia via Cape Comfort in August 1619 as indentured servants.[21] As many Virginian settlers began to die from harsh conditions, more and more Africans were brought to work as laborers.[22]

An indentured servant (who could be White or Black) would work for several years (usually four to seven) without wages. The status of indentured servants in early Virginia and Maryland was similar to slavery. Servants could be bought, sold, or leased, and they could be physically beaten for disobedience or attempting to running away. Unlike slaves, they were freed after their term of service expired or if their freedom was purchased. Their children did not inherit their status, and on their release from contract they received "a year's provision of corn, double apparel, tools necessary", and a small cash payment called "freedom dues".[23] Africans could legally raise crops and cattle to purchase their freedom.[24] They raised families, married other Africans and sometimes intermarried with Native Americans or European settlers.[25]

By the 1640s and 1650s, several African families owned farms around Jamestown, and some became wealthy by colonial standards and purchased indentured servants of their own. In 1640, the Virginia General Court recorded the earliest documentation of lifetime slavery when they sentenced John Punch, a Negro, to lifetime servitude under his master Hugh Gwyn, for running away.[27][28]

In Spanish Florida, some Spanish married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek or African women, both enslaved and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizos and mulattos. The Spanish encouraged slaves from the colony of Georgia to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism. King Charles II issued a royal proclamation freeing all slaves who fled to Spanish Florida and accepted conversion and baptism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine, but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola. St. Augustine had mustered an all-Black militia unit defending Spanish Florida as early as 1683.[29]

One of the Dutch African arrivals, Anthony Johnson, would later own one of the first Black "slaves", John Casor, resulting from the court ruling of a civil case.[30][31]

The popular conception of a race-based slave system did not fully develop until the 18th century. The Dutch West India Company introduced slavery in 1625 with the importation of eleven Black slaves into New Amsterdam (present-day New York City). All the colony's slaves, however, were freed upon its surrender to the English.[32]

Massachusetts was the first English colony to legally recognize slavery in 1641. In 1662, Virginia passed a law that children of enslaved women would take the status of the mother, rather than that of the father, as was the case under common law. This legal principle was called partus sequitur ventrum.[33][34]

By an act of 1699, Virginia ordered the deportation of all free Blacks, effectively defining all people of African descent who remained in the colony as slaves.[35] In 1670, the colonial assembly passed a law prohibiting free and baptized Blacks (and Native Americans) from purchasing Christians (in this act meaning White Europeans) but allowing them to buy people "of their owne nation".[36]

In Spanish Louisiana, although there was no movement toward abolition of the African slave trade, Spanish rule introduced a new law called coartación, which allowed slaves to buy their freedom, and that of others.[39] Although some did not have the money to do so, government measures on slavery enabled the existence of many free Blacks. This caused problems to the Spaniards with the French creoles (French who had settled in New France) who had also populated Spanish Louisiana. The French creoles cited that measure as one of the system's worst elements.[40]

First established in South Carolina in 1704, groups of armed White men—slave patrols—were formed to monitor enslaved Black people.[41] Their function was to police slaves, especially fugitives. Slave owners feared that slaves might organize revolts or slave rebellions, so state militias were formed to provide a military command structure and discipline within the slave patrols. These patrols were used to detect, encounter, and crush any organized slave meetings which might lead to revolts or rebellions.[41]

The earliest African American congregations and churches were organized before 1800 in both northern and southern cities following the Great Awakening. By 1775, Africans made up 20% of the population in the American colonies, which made them the second largest ethnic group after English Americans.[42]

From the American Revolution to the Civil War

During the 1770s, Africans, both enslaved and free, helped rebellious American colonists secure their independence by defeating the British in the American Revolutionary War.[43] Blacks played a role in both sides in the American Revolution. Activists in the Patriot cause included James Armistead, Prince Whipple, and Oliver Cromwell.[44][45] Around 15,000 Black Loyalists left with the British after the war, most of them ending up as free Black people in England[46] or its colonies, such as the Black Nova Scotians and the Sierra Leone Creole people.[47][48]

In the Spanish Louisiana, Governor Bernardo de Gálvez organized Spanish free Black men into two militia companies to defend New Orleans during the American Revolution. They fought in the 1779 battle in which Spain captured Baton Rouge from the British. Gálvez also commanded them in campaigns against the British outposts in Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. He recruited slaves for the militia by pledging to free anyone who was seriously wounded and promised to secure a low price for coartación (buy their freedom and that of others) for those who received lesser wounds. During the 1790s, Governor Francisco Luis Héctor, baron of Carondelet reinforced local fortifications and recruit even more free Black men for the militia. Carondelet doubled the number of free Black men who served, creating two more militia companies—one made up of Black members and the other of pardo (mixed race). Serving in the militia brought free Black men one step closer to equality with Whites, allowing them, for example, the right to carry arms and boosting their earning power. However, actually these privileges distanced free Black men from enslaved Blacks and encouraged them to identify with Whites.[40]

Slavery had been tacitly enshrined in the US Constitution through provisions such as Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, commonly known as the 3/5 compromise. Due to the restrictions of Section 9, Clause 1, Congress was unable to pass an Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves until 1807.[49] Fugitive slave laws (derived from the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution—Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3) were passed by Congress in both 1793 and 1850, guaranteeing the right of a slaveholder to recover an escaped slave anywhere within the US.[38] Slave owners, who viewed enslaved people as property, ensured that it became a federal crime to aid or assist those who had fled slavery or to interfere with their capture.[37] By that time, slavery, which almost exclusively targeted Black people, had become the most critical and contentious political issue in the Antebellum United States, repeatedly sparking crises and conflicts. Among these were the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the infamous Dred Scott decision, and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.

Prior to the Civil War, eight serving presidents had owned slaves, a practice that was legally protected under the US Constitution.[50] By 1860, the number of enslaved Black people in the US had grown to between 3.5 to 4.4 million, largely as a result of the Atlantic slave trade. In addition, 488,000–500,000 Black people lived free (with legislated limits)[51] across the country.[52] With legislated limits imposed upon them in addition to "unconquerable prejudice" from Whites according to Henry Clay.[53] In response to these conditions, some free Black people chose to leave the US and emigrate to Liberia in West Africa.[51] Liberia had been established in 1821 as a settlement by the American Colonization Society (ACS), with many abolitionist members of the ACS believing Black Americans would have greater opportunities for freedom and equality in Africa than they would in the US.[51]

Slaves not only represented a significant financial investment for their owners, but they also played a crucial role in producing the country's most valuable product and export: cotton. Enslaved people were instrumental in the construction of several prominent structures such as, the United States Capitol, the White House and other Washington, D.C.-based buildings.[54]) Similar building projects existed in the slave states.

By 1815, the domestic slave trade had become a significant and major economic activity in the United States, continuing to flourish until the 1860s.[55] Historians estimate that nearly one million individuals were subjected to this forced migration, which was often referred to as a new "Middle Passage". The historian Ira Berlin described this internal forced migration of enslaved people as the "central event" in the life of a slave during the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Berlin emphasized that whether enslaved individuals were directly uprooted or lived in constant fear that they or their families would be involuntarily relocated, "the massive deportation traumatized Black people" throughout the US.[56] As a result of this large-scale forced movement, countless individuals lost their connection to families and clans, and many ethnic Africans lost their knowledge of varying tribal origins in Africa.[55]

The 1863 photograph of Wilson Chinn, a branded slave from Louisiana, along with the famous image of Gordon and his scarred back, served as two of the earliest and most powerful examples of how the newborn medium of photography could be used to visually document and encapsulate the brutality and cruelty of slavery.[57]

Emigration of free Blacks to their continent of origin had been proposed since the Revolutionary war. After Haiti became independent, it tried to recruit African Americans to migrate there after it re-established trade relations with the United States. The Haitian Union was a group formed to promote relations between the countries.[58] After riots against Blacks in Cincinnati, its Black community sponsored founding of the Wilberforce Colony, an initially successful settlement of African American immigrants to Canada. The colony was one of the first such independent political entities. It lasted for a number of decades and provided a destination for about 200 Black families emigrating from a number of locations in the United States.[58]

In 1863, during the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation declared that all slaves in Confederate-held territory were free.[59] Advancing Union troops enforced the proclamation, with Texas being the last state to be emancipated, in 1865.[60]

Slavery in a few border states continued until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865.[61] While the Naturalization Act of 1790 limited US citizenship to Whites only,[62][63] the 14th Amendment (1868) gave Black people citizenship, and the 15th Amendment (1870) gave Black men the right to vote.[64]

Reconstruction era and Jim Crow

African Americans quickly set up congregations for themselves, as well as schools and community/civic associations, to have space away from White control or oversight. While the post-war Reconstruction era was initially a time of progress for African Americans, that period ended in 1876. By the late 1890s, Southern states enacted Jim Crow laws to enforce racial segregation and disenfranchisement.[65] Segregation was now imposed with Jim Crow laws, using signs used to show Blacks where they could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat.[66] For those places that were racially mixed, non-Whites had to wait until all White customers were dealt with.[66] Most African Americans obeyed the Jim Crow laws, to avoid racially motivated violence. To maintain self-esteem and dignity, African Americans such as Anthony Overton and Mary McLeod Bethune continued to build their own schools, churches, banks, social clubs, and other businesses.[67]

In the last decade of the 19th century, racially discriminatory laws and racial violence aimed at African Americans began to mushroom in the United States, a period often referred to as the "nadir of American race relations". These discriminatory acts included racial segregation—upheld by the United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896—which was legally mandated by southern states and nationwide at the local level of government, voter suppression or disenfranchisement in the southern states, denial of economic opportunity or resources nationwide, and private acts of violence and mass racial violence aimed at African Americans unhindered or encouraged by government authorities.[68]

Great migration and civil rights movement

The desperate conditions of African Americans in the South sparked the Great Migration during the first half of the 20th century which led to a growing African American community in Northern and Western United States.[70] The rapid influx of Blacks disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both Blacks and Whites in the two regions.[71] The Red Summer of 1919 was marked by hundreds of deaths and higher casualties across the US as a result of race riots that occurred in more than three dozen cities, such as the Chicago race riot of 1919 and the Omaha race riot of 1919. Overall, Blacks in Northern and Western cities experienced systemic discrimination in a plethora of aspects of life. Within employment, economic opportunities for Blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. At the 1900 Hampton Negro Conference, Reverend Matthew Anderson said: "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South."[72] Within the housing market, stronger discriminatory measures were used in correlation to the influx, resulting in a mix of "targeted violence, restrictive covenants, redlining and racial steering".[73] While many Whites defended their space with violence, intimidation, or legal tactics toward African Americans, many other Whites migrated to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions, a process known as White flight.[74]

Despite discrimination, drawing cards for leaving the hopelessness in the South were the growth of African American institutions and communities in Northern cities. Institutions included Black oriented organizations (e.g., Urban League, NAACP), churches, businesses, and newspapers, as well as successes in the development in African American intellectual culture, music, and popular culture (e.g., Harlem Renaissance, Chicago Black Renaissance). The Cotton Club in Harlem was a Whites-only establishment, with Blacks (such as Duke Ellington) allowed to perform, but to a White audience.[75] Black Americans also found a new ground for political power in Northern cities, without the enforced disabilities of Jim Crow.[76][77]

By the 1950s, the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. A 1955 lynching that sparked public outrage about injustice was that of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago. Spending the summer with relatives in Money, Mississippi, Till was killed for allegedly having wolf-whistled at a White woman. Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out, and he was shot in the head. The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the Black community throughout the US.[78] Vann R. Newkirk wrote "the trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of White supremacy".[78] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-White jury.[79] One hundred days after Emmett Till's murder, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus in Alabama—indeed, Parks told Emmett's mother Mamie Till that "the photograph of Emmett's disfigured face in the casket was set in her mind when she refused to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus."[80]

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the conditions which brought it into being are credited with putting pressure on presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson put his support behind passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that banned discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and labor unions, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which expanded federal authority over states to ensure Black political participation through protection of voter registration and elections.[81] By 1966, the emergence of the Black Power movement, which lasted from 1966 to 1975, expanded upon the aims of the civil rights movement to include economic and political self-sufficiency, and freedom from White authority.[82]

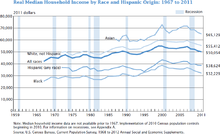

During the post-war period, many African Americans continued to be economically disadvantaged relative to other Americans. Average Black income stood at 54 percent of that of White workers in 1947, and 55 percent in 1962. In 1959, median family income for Whites was $5,600 (equivalent to $58,532 in 2023), compared with $2,900 (equivalent to $30,311 in 2023) for non-White families. In 1965, 43 percent of all Black families fell into the poverty bracket, earning under $3,000 (equivalent to $29,005 in 2023) a year. The 1960s saw improvements in the social and economic conditions of many Black Americans.[83]

From 1965 to 1969, Black family income rose from 54 to 60 percent of White family income. In 1968, 23 percent of Black families earned under $3,000 (equivalent to $26,285 in 2023) a year, compared with 41 percent in 1960. In 1965, 19 percent of Black Americans had incomes equal to the national median, a proportion that rose to 27 percent by 1967. In 1960, the median level of education for Blacks had been 10.8 years, and by the late 1960s, the figure rose to 12.2 years, half a year behind the median for Whites.[83]

Post–civil rights era

Politically and economically, African Americans have made substantial strides during the post–civil rights era. In 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first African American Supreme Court Justice. In 1968, Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to the US Congress. In 1989, Douglas Wilder became the first African American elected governor in US history. Clarence Thomas succeeded Marshall to become the second African American Supreme Court Justice in 1991. In 1992, Carol Moseley-Braun of Illinois became the first African American woman elected to the US Senate. There were 8,936 Black officeholders in the United States in 2000, showing a net increase of 7,467 since 1970. In 2001, there were 484 Black mayors.[84]

In 2005, the number of Africans immigrating to the United States, in a single year, surpassed the peak number who were involuntarily brought to the United States during the Atlantic slave trade.[85] On November 4, 2008, Democratic Senator Barack Obama—the son of a White American mother and a Kenyan father—defeated Republican Senator John McCain to become the first African American to be elected president. At least 95 percent of African American voters voted for Obama.[86][87] He also received overwhelming support from young and educated Whites, a majority of Asians,[88] and Hispanics,[88] picking up a number of new states in the Democratic electoral column.[86][87] Obama lost the overall White vote, although he won a larger proportion of White votes than any previous non-incumbent Democratic presidential candidate since Jimmy Carter.[89] Obama was reelected for a second and final term, by a similar margin on November 6, 2012.[90] In 2021, Kamala Harris, the daughter of a Jamaican father and Indian mother, became the first woman, the first African American, and the first Asian American to serve as Vice President of the United States.[91] In June 2021, Juneteenth, a day which commemorates the end of slavery in the US, became a federal holiday.[92]

Demographics

In 1790, when the first US census was taken, Africans (including slaves and free people) numbered about 760,000—about 19.3% of the population. In 1860, at the start of the Civil War, the African American population had increased to 4.4 million, but the percentage rate dropped to 14% of the overall population of the country. The vast majority were slaves, with only 488,000 counted as "freemen". By 1900, the Black population had doubled and reached 8.8 million.[93]

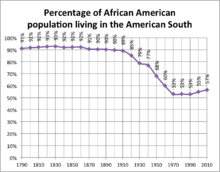

In 1910, about 90% of African Americans lived in the South. Large numbers began migrating north looking for better job opportunities and living conditions, and to escape Jim Crow laws and racial violence. The Great Migration, as it was called, spanned the 1890s to the 1970s. From 1916 through the 1960s, more than 6 million Black people moved north. But in the 1970s and 1980s, that trend reversed, with more African Americans moving south to the Sun Belt than leaving it.[94]

The following table of the African American population in the United States over time shows that the African American population, as a percentage of the total population, declined until 1930 and has been rising since then.

| Year | Number | % of total population |

% Change (10 yr) |

Slaves | % in slavery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 757,208 | 19.3% (highest) | – | 697,681 | 92% |

| 1800 | 1,002,037 | 18.9% | 32.3% | 893,602 | 89% |

| 1810 | 1,377,808 | 19.0% | 37.5% | 1,191,362 | 86% |

| 1820 | 1,771,656 | 18.4% | 28.6% | 1,538,022 | 87% |

| 1830 | 2,328,642 | 18.1% | 31.4% | 2,009,043 | 86% |

| 1840 | 2,873,648 | 16.8% | 23.4% | 2,487,355 | 87% |

| 1850 | 3,638,808 | 15.7% | 26.6% | 3,204,287 | 88% |

| 1860 | 4,441,830 | 14.1% | 22.1% | 3,953,731 | 89% |

| 1870 | 4,880,009 | 12.7% | 9.9% | – | – |

| 1880 | 6,580,793 | 13.1% | 34.9% | – | – |

| 1890 | 7,488,788 | 11.9% | 13.8% | – | – |

| 1900 | 8,833,994 | 11.6% | 18.0% | – | – |

| 1910 | 9,827,763 | 10.7% | 11.2% | – | – |

| 1920 | 10.5 million | 9.9% | 6.8% | – | – |

| 1930 | 11.9 million | 9.7% (lowest) | 13% | – | – |

| 1940 | 12.9 million | 9.8% | 8.4% | – | – |

| 1950 | 15.0 million | 10.0% | 16% | – | – |

| 1960 | 18.9 million | 10.5% | 26% | – | – |

| 1970 | 22.6 million | 11.1% | 20% | – | – |

| 1980 | 26.5 million | 11.7% | 17% | – | – |

| 1990 | 30.0 million | 12.1% | 13% | – | – |

| 2000 | 34.6 million | 12.3% | 15% | – | – |

| 2010 | 38.9 million | 12.6% | 12% | – | – |

| 2020 | 41.1 million | 12.4% | 5.6% | – | – |

By 1990, the African American population reached about 30 million and represented 12% of the US population, roughly the same proportion as in 1900.[96]

| Years | Non-Hispanic Blacks | Black Hispanics | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | ||

| 2020 | 39,940,338 | 12.1% | 1,163,862 | 0.3' % | 41,104,200 |

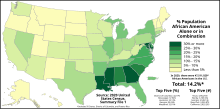

At the time of the 2000 US census, 54.8% of African Americans lived in the South. In that year, 17.6% of African Americans lived in the Northeast and 18.7% in the Midwest, while only 8.9% lived in the Western states. The west does have a sizable Black population in certain areas, however. California, the nation's most populous state, has the fifth largest African American population, only behind New York, Texas, Georgia, and Florida. According to the 2000 census, approximately 2.05% of African Americans identified as Hispanic or Latino in origin,[97] many of whom may be of Brazilian, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Cuban, Haitian, or other Latin American descent. The only self-reported ancestral groups larger than African Americans are the Irish and Germans.[98]

According to the 2010 census, nearly 3% of people who self-identified as Black had recent ancestors who immigrated from another country. Self-reported non-Hispanic Black immigrants from the Caribbean, mostly from Jamaica and Haiti, represented 0.9% of the US population, at 2.6 million.[100] Self-reported Black immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa also represented 0.9%, at about 2.8 million.[100] Additionally, self-identified Black Hispanics represented 0.4% of the United States population, at about 1.2 million people, largely found within the Puerto Rican and Dominican communities.[101] Self-reported Black immigrants hailing from other countries in the Americas, such as Brazil and Canada, as well as several European countries, represented less than 0.1% of the population. Mixed-race Hispanic and non-Hispanic Americans who identified as being part Black, represented 0.9% of the population. Of the 12.6% of United States residents who identified as Black, around 10.3% were "native Black American" or ethnic African Americans, who are direct descendants of West/Central Africans brought to the US as slaves. These individuals make up well over 80% of all Blacks in the country. When including people of mixed-race origin, about 13.5% of the US population self-identified as Black or "mixed with Black".[102] However, according to the US Census Bureau, evidence from the 2000 census indicates that many African and Caribbean immigrant ethnic groups do not identify as "Black, African Am., or Negro". Instead, they wrote in their own respective ethnic groups in the "Some Other Race" write-in entry. As a result, the census bureau devised a new, separate "African American" ethnic group category in 2010 for ethnic African Americans.[103] Nigerian Americans and Ethiopian Americans were the most reported sub-Saharan African groups in the United States.[104]

Historically, African Americans have been undercounted in the US census due to a number of factors.[example needed][105][106] In the 2020 census, the African American population was undercounted at an estimated rate of 3.3%, up from 2.1% in 2010.[107]

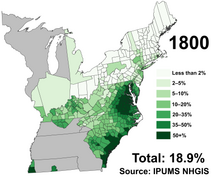

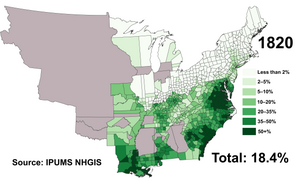

Proportion in each county

- African American (Alone) population distribution over time

-

1790

-

1800

-

1810

-

1820

-

1830

-

1840

-

1850

-

1860

-

1870

-

1880

-

1890

-

1900

-

1910

-

1920

-

1930

-

1940

-

1970

-

1980

-

1990

-

2000

-

2010

-

2020

Texas has the largest African American population by state. Followed by Texas is Florida, with 3.8 million, and Georgia, with 3.6 million.[108]

US cities

After 100 years of African Americans leaving the south in large numbers seeking better opportunities and treatment in the west and north, a movement known as the Great Migration, there is now a reverse trend, called the New Great Migration. As with the earlier Great Migration, the New Great Migration is primarily directed toward cities and large urban areas, such as Charlotte, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Huntsville, Raleigh, Tampa, San Antonio, New Orleans, Memphis, Nashville, Jacksonville, and so forth.[109] A growing percentage of African Americans from the west and north are migrating to the southern region of the US for economic and cultural reasons. The New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles metropolitan areas have the highest decline in African Americans, while Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston have the highest increase respectively.[109] Several smaller metro areas also saw sizable gains, including San Antonio;[110] Raleigh and Greensboro, N.C.; and Orlando.[111] Despite recent declines, as of 2020, the New York City metropolitan area still has the largest African American metropolitan population in the United States and the only to have over 3 million African Americans.[112][113]

Among cities of 100,000 or more, South Fulton, Georgia had the highest percentage of Black residents of any large US city in 2020, with 93%. Other large cities with African American majorities include Jackson, Mississippi (80%), Detroit, Michigan (80%), Birmingham, Alabama (70%), Miami Gardens, Florida (67%), Memphis, Tennessee (63%), Montgomery, Alabama (62%), Baltimore, Maryland (60%), Augusta, Georgia (59%), Shreveport, Louisiana (58%), New Orleans, Louisiana (57%), Macon, Georgia (56%), Baton Rouge, Louisiana (55%), Hampton, Virginia (53%), Newark, New Jersey (53%), Mobile, Alabama (53%), Cleveland, Ohio (52%), Brockton, Massachusetts (51%), and Savannah, Georgia (51%).

The nation's most affluent community with an African American majority resides in View Park–Windsor Hills, California, with an annual median household income of $159,618.[114] Other largely affluent and African American communities include Prince George's County (namely Mitchellville, Woodmore, Upper Marlboro) and Charles County in Maryland,[115] Dekalb County (namely Stonecrest, Lithonia, Smoke Rise) and South Fulton in Georgia, Charles City County in Virginia, Baldwin Hills in California, Hillcrest and Uniondale in New York, and Cedar Hill, DeSoto, and Missouri City in Texas. Additionally, there is a significant affluent Black presence in the southern Chicago suburbs of Cook County, Illinois. A report from the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB) indicated that 5 of the top 10 municipalities nationwide (with at least 500 Black households) registering the highest Black homeownership rates were in this area - including Olympia Fields, South Holland, Flossmoor, Matteson, and Lynwood.[116] Queens County, New York is the only county with a population of 65,000 or more where African Americans have a higher median household income than White Americans.[117]

Seatack, Virginia is currently the oldest African American community in the United States.[118] It survives today with a vibrant and active civic community.[119]

Education

During slavery, anti-literacy laws were enacted in the US that prohibited education for Black people. Slave owners saw literacy as a threat to the institution of slavery. As a North Carolina statute stated, "Teaching slaves to read and write, tends to excite dissatisfaction in their minds, and to produce insurrection and rebellion."[120]

When slavery was finally abolished in 1865, public educational systems were expanding across the country. By 1870, around seventy-four institutions in the south provided a form of advanced education for African American students. By 1900, over a hundred programs at these schools provided training for Black professionals, including teachers. Many of the students at Fisk University, including the young W. E. B. Du Bois, taught school during the summers to support their studies.[121]

African Americans were very concerned to provide quality education for their children, but White supremacy limited their ability to participate in educational policymaking on the political level. State governments soon moved to undermine their citizenship by restricting their right to vote. By the late 1870s, Blacks were disenfranchised and segregated across the American South.[122] White politicians in Mississippi and other states withheld financial resources and supplies from Black schools. Nevertheless, the presence of Black teachers, and their engagement with their communities both inside and outside the classroom, ensured that Black students had access to education despite these external constraints.[123][124]

During World War II, demands for unity and racial tolerance on the home front provided an opening for the first Black history curriculum in the country.[125] For example, during the early 1940s, Madeline Morgan, a Black teacher in the Chicago public schools, created a curriculum for students in grades one through eight highlighting the contributions of Black people to the history of the United States. At the close of the war, Chicago's Board of Education downgraded the curriculum's status from mandatory to optional.[126]

Predominantly Black schools for kindergarten through twelfth grade students were common throughout the US before the 1970s. By 1972, however, desegregation efforts meant that only 25% of Black students were in schools with more than 90% non-White students. However, since then, a trend towards re-segregation affected communities across the country: by 2011, 2.9 million African American students were in such overwhelmingly minority schools, including 53% of Black students in school districts that were formerly under desegregation orders.[127][128]

As late as 1947, about one third of African Americans over 65 were considered to lack the literacy to read and write their own names. By 1969, illiteracy as it had been traditionally defined, had been largely eradicated among younger African Americans.[129]

US census surveys showed that by 1998, 89 percent of African Americans aged 25 to 29 had completed a high-school education, less than Whites or Asians, but more than Hispanics. On many college and university entrance exams or on standardized tests and grades, African Americans have historically lagged behind Whites, but some studies suggest that the achievement gap has been closing. Many policy makers have proposed that this gap can and will be eliminated through policies such as affirmative action, desegregation, and multiculturalism.[130]

Between 1995 and 2009, freshmen college enrollment for African Americans increased by 73 percent and only 15 percent for Whites.[131] Black women are enrolled in college more than any other race and gender group, leading all with 9.7% enrolled according to the 2011 US census.[132][133] The average high school graduation rate of Blacks in the United States has steadily increased to 71% in 2013.[134] Separating this statistic into component parts shows it varies greatly depending upon the state and the school district examined. 38% of Black males graduated in the state of New York but in Maine 97% graduated and exceeded the White male graduation rate by 11 percentage points.[135] In much of the southeastern United States and some parts of the southwestern United States the graduation rate of White males was in fact below 70% such as in Florida where 62% of White males graduated from high school. Examining specific school districts paints an even more complex picture. In the Detroit school district, the graduation rate of Black males was 20% but 7% for White males. In the New York City school district 28% of Black males graduate from high school compared to 57% of White males. In Newark County[where?] 76% of Black males graduated compared to 67% for White males. Further academic improvement has occurred in 2015. Roughly 23% of all Blacks have bachelor's degrees. In 1988, 21% of Whites had obtained a bachelor's degree versus 11% of Blacks. In 2015, 23% of Blacks had obtained a bachelor's degree versus 36% of Whites.[136] Foreign born Blacks, 9% of the Black population, made even greater strides. They exceed native born Blacks by 10 percentage points.[136]

College Board, which runs the official college-level advanced placement (AP) programs in American high schools, have has received criticism in recent years that its curricula have focused too much on Euro-centric history.[137] In 2020, College Board reshaped some curricula among history-based courses to further reflect the African diaspora.[138] In 2021, College Board announced it would be piloting an AP African American Studies course between 2022 and 2024. The course is expected to launch in 2024.[139]

Historically Black colleges and universities

Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), which were founded when segregated institutions of higher learning did not admit African Americans, continue to thrive and educate students of all races today. There are 101 HBCUs representing three percent of the nation's colleges and universities with the majority established in the Southeast.[140][141] HBCUs have been largely responsible for establishing and expanding the African American middle-class by providing more career opportunities for African Americans.[142][143]

Economic status

The economic disparity between the races in the US has marginally improved since the end of slavery. In 1863, two years prior to emancipation, Black people owned 0.5 percent of the national wealth, while in 2019 it is just over 1.5 percent.[144] Racial disparity in poverty rates has narrowed since the civil rights era, with the poverty rate among African Americans decreasing from 24.7% in 2004 to 18.8% in 2020, compared to 10.5% for all Americans.[145][146] Poverty is associated with higher rates of marital stress and dissolution, physical and mental health problems, disability, cognitive deficits, low educational attainment, and crime.[147]

African Americans have a long and diverse history of business ownership. Although the first African American business is unknown, slaves captured from West Africa are believed to have established commercial enterprises as peddlers and skilled craftspeople as far back as the 17th century. Around 1900, Booker T. Washington became the most famous proponent of African American businesses. His critic and rival W. E. B. DuBois also commended business as a vehicle for African American advancement.[148]

African Americans had a combined buying power of over $1.6 trillion as of 2021, a 171% increase of their buying power in 2000 but lagging significantly in growth behind American Latinos and Asians in the same timer period (with 288% and 383%, respectively; for reference, US growth overall was 144% in the same period); however, African American net worth had shrunk 14% in the previous year despite strong growth in property prices and the S&P 500. In 2002, African American-owned businesses accounted for 1.2 million of the US's 23 million businesses.[150] As of 2011[update], African American-owned businesses account for approximately 2 million US businesses.[151] Black-owned businesses experienced the largest growth in number of businesses among minorities from 2002 to 2011.[151]

Twenty-five percent of Blacks had white-collar occupations (management, professional, and related fields) in 2000, compared with 33.6% of Americans overall.[152][153] In 2001, over half of African American households of married couples earned $50,000 or more.[153] Although in the same year African Americans were over-represented among the nation's poor, this was directly related to the disproportionate percentage of African American families headed by single women; such families are collectively poorer, regardless of ethnicity.[153]

In 2006, the median earnings of African American men was more than Black and non-Black American women overall, and in all educational levels.[154][155][156][157][158] At the same time, among American men, income disparities were significant; the median income of African American men was approximately 76 cents for every dollar of their European American counterparts, although the gap narrowed somewhat with a rise in educational level.[154][159]

Overall, the median earnings of African American men were 72 cents for every dollar earned of their Asian American counterparts, and $1.17 for every dollar earned by Hispanic men.[154][157][160] On the other hand, by 2006, among American women with post-secondary education, African American women have made significant advances; the median income of African American women was more than those of their Asian-, European- and Hispanic American counterparts with at least some college education.[155][156][161]

The US public sector is the single most important source of employment for African Americans.[162] During 2008–2010, 21.2% of all Black workers were public employees, compared with 16.3% of non-Black workers.[162] Both before and after the onset of the Great Recession, African Americans were 30% more likely than other workers to be employed in the public sector.[162] The public sector is also a critical source of decent-paying jobs for Black Americans. For both men and women, the median wage earned by Black employees is significantly higher in the public sector than in other industries.[162]

In 1999, the median income of African American families was $33,255 compared to $53,356 of European Americans. In times of economic hardship for the nation, African Americans suffer disproportionately from job loss and underemployment, with the Black underclass being hardest hit. The phrase "last hired and first fired" is reflected in the Bureau of Labor Statistics unemployment figures. Nationwide, the October 2008 unemployment rate for African Americans was 11.1%,[163] while the nationwide rate was 6.5%.[164] In 2007, the average income for African Americans was approximately $34,000, compared to $55,000 for Whites.[165] African Americans experience a higher rate of unemployment than the general population.[166]

The income gap between Black and White families is also significant. In 2005, employed Blacks earned 65% of the wages of Whites, down from 82% in 1975.[145] The New York Times reported in 2006 that in Queens, New York, the median income among African American families exceeded that of White families, which the newspaper attributed to the growth in the number of two-parent Black families. It noted that Queens was the only county with more than 65,000 residents where that was true.[117] In 2011, it was reported that 72% of Black babies were born to unwed mothers.[167] The poverty rate among single-parent Black families was 39.5% in 2005, according to Walter E. Williams, while it was 9.9% among married-couple Black families. Among White families, the respective rates were 26.4% and 6% in poverty.[168]

Collectively, African Americans are more involved in the American political process than other minority groups in the United States, indicated by the highest level of voter registration and participation in elections among these groups in 2004.[169] African Americans also have the highest level of Congressional representation of any minority group in the US.[170]

African American homeownership

Homeownership in the US is the strongest indicator of financial stability and the primary asset most Americans use to generate wealth. African Americans continue to lag behind other racial groups in homeownership.[172] In the first quarter of 2021, 45.1% of African Americans owned their homes, compared to 65.3% of all Americans.[173] The African American homeownership rate has remained relatively flat since the 1970s despite an increase in anti-discrimination housing laws and protections.[174] The African American homeownership rate peaked in 2004 at 49.7%.[175]

The average White high school drop-out still has a slightly better chance of owning a home than the average African American college graduate usually due to unfavorable debt-to-income ratios or credit scores among most African American college graduates.[176][177] Since 2000, fast-growing housing costs in most cities have made it even more difficult for the US African American homeownership rate to significantly grow and reach over 50% for the first time in history. From 2000 to 2022, the median home price in the US grew 160%, outpacing average annual household income growth in that same period, which only grew about 30%.[178][179][180] South Carolina is the state with the most African American homeownership, with about 55% of African Americans owning their own homes.[181][182]

Politics

| Year | Candidate of the plurality |

Political party |

% of Black vote |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Jimmy Carter | Democratic | 83% | Lost |

| 1984 | Walter Mondale | Democratic | 91% | Lost |

| 1988 | Michael Dukakis | Democratic | 89% | Lost |

| 1992 | Bill Clinton | Democratic | 83% | Won |

| 1996 | Bill Clinton | Democratic | 84% | Won |

| 2000 | Al Gore | Democratic | 90% | Lost |

| 2004 | John Kerry | Democratic | 88% | Lost |

| 2008 | Barack Obama | Democratic | 95% | Won |

| 2012 | Barack Obama | Democratic | 93% | Won |

| 2016 | Hillary Clinton | Democratic | 88% | Lost |

| 2020 | Joe Biden | Democratic | 87% | Won |

| 2024 | Kamala Harris | Democratic | 85% | Lost |

Since the mid 20th century, a large majority of African Americans support the Democratic Party. In the 2020 Presidential election, 91% of African American voters supported Democrat Joe Biden, while 8% supported Republican Donald Trump.[183] Although there is an African American lobby in foreign policy, it has not had the impact that African American organizations have had in domestic policy.[184]

Many African Americans were excluded from electoral politics in the decades following the end of Reconstruction. For those that could participate, until the New Deal, African Americans were supporters of the Republican Party because it was Republican President Abraham Lincoln who helped in granting freedom to American slaves; at the time, the Republicans and Democrats represented the sectional interests of the North and South, respectively, rather than any specific ideology, and both conservative and liberal were represented equally in both parties.

The African American trend of voting for Democrats can be traced back to the 1930s during the Great Depression, when Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal program provided economic relief to African Americans. Roosevelt's New Deal coalition turned the Democratic Party into an organization of the working class and their liberal allies, regardless of region. The African American vote became even more solidly Democratic when Democratic presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson pushed for civil rights legislation during the 1960s. In 1960, nearly a third of African Americans voted for Republican Richard Nixon.[185]

Black national anthem

"Lift Every Voice and Sing" is often referred to as the Black national anthem in the United States.[186] In 1919, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had dubbed it the "Negro national anthem" for its power in voicing a cry for liberation and affirmation for African-American people.[187]

Sexuality

According to a Gallup survey, 4.6% of Black or African Americans self-identified as LGBT in 2016,[188] while the total portion of American adults in all ethnic groups identifying as LGBT was 4.1% in 2016.[188] African Americans are more likely to identify themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States.[189]

Health

General health

The life expectancy for Black men in 2008 was 70.8 years.[190] Life expectancy for Black women was 77.5 years in 2008.[190] In 1900, when information on Black life expectancy started being collated, a Black man could expect to live to 32.5 years and a Black woman 33.5 years.[190] In 1900, White men lived an average of 46.3 years and White women lived an average of 48.3 years.[190] African American life expectancy at birth is persistently five to seven years lower than European Americans.[191] Black men have shorter lifespans than any other group in the US besides Native American men.[192]

Black people have higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension than the US average.[190] For adult Black men, the rate of obesity was 31.6% in 2010.[193] For adult Black women, the rate of obesity was 41.2% in 2010.[193] African Americans have higher rates of mortality than any other racial or ethnic group for 8 of the top 10 causes of death.[194] In 2013, among men, Black men had the highest rate of getting cancer, followed by White, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander (A/PI), and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) men. Among women, White women had the highest rate of getting cancer, followed by Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native women.[195] African Americans also have higher prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease compared to the overall average.[196][197]

African-Americans are more likely than White Americans to die due to health-related problems developed by alcoholism. Alcohol abuse is the main contributor to the top 3 causes of death among African Americans.[198]

In December 2020, African Americans were less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19 due to mistrust in the US medical system. From 2021 to 2022, there was an increase in African Americans who became vaccinated.[199][200][201] Still, in 2022, COVID-19 complications became the third leading cause of death for African Americans.[202]

Violence is a major problem within the African American community.[203][204] A report from the US Department of Justice states "In 2005, homicide victimization rates for Blacks were 6 times higher than the rates for whites".[205] The report also found that "94% of Black victims were killed by Blacks."[205] Of the nearly 20,000 recorded US homicides in 2022, African Americans made up the majority of offenders and victims despite making up less than 20% of the population.[206] In 2024, all of the top 5 most dangerous US cities have a significant Black population and disturbing Black-on-Black violent crime rate.[207] Black males age 15–44 are the only race/sex category for which homicide is a top 5 cause of death.[192] Black women are 3 times more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than white women.[208] Black children are 3 times more likely to die due to parental abuse and neglect than white children.[209]

Sexual health

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, African Americans have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) compared to Whites, with 5 times the rates of syphilis and chlamydia, and 7.5 times the rate of gonorrhea.[210]

The disproportionately high incidence of HIV/AIDS among African Americans has been attributed to homophobic influences and lack of proper healthcare.[211] The prevalence of HIV/AIDS among Black men is seven times higher than the prevalence for White men, and Black men are more than nine times as likely to die from HIV/AIDS-related illness than White men.[192]

Mental health

African Americans have several barriers for accessing mental health services. Counseling has been frowned upon and distant in utility and proximity to many people in the African American community. In 2004, a qualitative research study explored the disconnect with African Americans and mental health. The study was conducted as a semi-structured discussion which allowed the focus group to express their opinions and life experiences. The results revealed a couple key variables that create barriers for many African American communities to seek mental health services such as the stigma, lack of four important necessities; trust, affordability, cultural understanding and impersonal services.[212]

Historically, many African American communities did not seek counseling because religion was a part of the family values.[213] African American who have a faith background are more likely to seek prayer as a coping mechanism for mental issues rather than seeking professional mental health services.[212] In 2015 a study concluded, African Americans with high value in religion are less likely to utilize mental health services compared to those who have low value in religion.[214]

In the United States, counseling approaches are based on the experience of White Americans and do not fit within the African American culture. African American families tend to resolve concerns within the family, and it is viewed by the family as a strength. On the other hand, when African Americans seek counseling, they face a social backlash and are criticized. They may be labeled "crazy", viewed as weak, and their pride is diminished.[212] Because of this, many African Americans instead seek mentorship within communities they trust.

Terminology is another barrier in relation to African Americans and mental health. There is more stigma on the term psychotherapy versus counseling. In one study, psychotherapy is associated with mental illness whereas counseling approaches problem-solving, guidance and help.[212] More African Americans seek assistance when it is called counseling and not psychotherapy because it is more welcoming within the cultural and community.[215] Counselors are encouraged to be aware of such barriers for the well-being of African American clients. Without cultural competency training in health care, many African Americans go unheard and misunderstood.[212]

In 2021, African Americans had the third highest suicide rate trailing American Indians/Alaska Natives and White Americans. However, African Americans had the second highest increase of its suicide rate from 2011 to 2021, growing 58%.[216] As of 2024, suicide is the second leading cause of death among African-Americans between the ages of 15 and 24, with Black men being four times more likely to kill themselves than Black women.[217]

Genetics

Genome-wide studies

Recent studies of African Americans using genetic testing have found ancestry to vary by region and sex of ancestors. These studies found that on average, African Americans have 73.2–82.1% Sub-Saharan African, 16.7–24% European, and 0.8–1.2% Native American genetic ancestry, with large variation between individuals.[219][220][221] Commercial testing services have reported similar variation, with ranges from 0.6 to 2 percent Native American, 19 to 29 percent European, and 65 to 80 percent Sub-Saharan African ancestry.[222]

According to a genome-wide study by Bryc et al. (2009), the mixed ancestry of African Americans in varying ratios came about as the result of sexual contact between West/Central Africans (more frequently females) and Europeans (more frequently males). This can be understood as being the result of enslaved African American females being raped by White males.[223] Historians estimate that 58% of enslaved women in the US aged 15–30 years were sexually assaulted by their slave owners and other White men.[224] Consequently, the 365 African Americans in their sample have a genome-wide average of 78.1% West African ancestry and 18.5% European ancestry, with large variation among individuals (ranging from 99% to 1% West African ancestry). The West African ancestral component in African Americans is most similar to that in present-day speakers from the non-Bantu branches of the Niger-Congo family.[219][note 2]

Correspondingly, Montinaro et al. (2014) observed that around 50% of the overall ancestry of African Americans traces comes from a population similar to the Niger-Congo-speaking Yoruba of southern Nigeria and southern Benin, reflecting the centrality of this West African region in the Atlantic slave trade. The next most frequent ancestral component found among African Americans was derived from Great Britain, in keeping with historical records. It constitutes a little over 10% of their overall ancestry and is most similar to the Northwest European ancestral component also carried by Barbadians.[226] Zakharia et al. (2009) found a similar proportion of Yoruba-like ancestry in their African American samples, with a minority also drawn from Mandenka and Bantu populations. Additionally, the researchers observed an average European ancestry of 21.9%, again with significant variation between individuals.[218] Bryc et al. (2009) note that populations from other parts of the continent may also constitute adequate proxies for the ancestors of some African American individuals; namely, ancestral populations from Guinea Bissau, Senegal and Sierra Leone in West Africa and Angola in Southern Africa.[219] An individual African American person can have over fifteen African ethnic groups in their genetic makeup alone due to the slave trade covering such vast areas.[227]

Altogether, genetic studies suggest that African Americans are a genetically diverse people. According to DNA analysis led in 2006 by Penn State geneticist Mark D. Shriver, around 58 percent of African Americans have at least 12.5% European ancestry (equivalent to one European great-grandparent and their forebears), 19.6 percent of African Americans have at least 25% European ancestry (equivalent to one European grandparent and their forebears), and 1 percent of African Americans have at least 50% European ancestry (equivalent to one European parent and their forebears).[10][228] According to Shriver, around 5 percent of African Americans also have at least 12.5% Native American ancestry (equivalent to one Native American great-grandparent and their forebears).[229][230] Research suggests that Native American ancestry among people who identify as African American is a result of relationships that occurred soon after slave ships arrived in the American colonies, and European ancestry is of more recent origin, often from the decades before the Civil War.[231]

Y-DNA

Africans bearing the E-V38 (E1b1a) likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west, approximately 19,000 years ago.[232] E-M2 (E1b1a1) likely originated in West Africa or Central Africa.[233] According to a Y-DNA study by Sims et al. (2007), the majority (≈60%) of African Americans belong to various subclades of the E-M2 (E1b1a1, formerly E3a) paternal haplogroup. This is the most common genetic paternal lineage found today among West/Central African males and is also a signature of the historical Bantu migrations. The next most frequent Y-DNA haplogroup observed among African Americans is the R1b clade, which around 15% of African Americans carry. This lineage is most common today among Northwestern European males. The remaining African Americans mainly belong to the paternal haplogroup I (≈7%), which is also frequent in Northwestern Europe.[234]

mtDNA

According to an mtDNA study by Salas et al. (2005), the maternal lineages of African Americans are most similar to haplogroups that are today especially common in West Africa (>55%), followed closely by West-Central Africa and Southwestern Africa (<41%). The characteristic West African haplogroups L1b, L2b,c,d, and L3b,d and West-Central African haplogroups L1c and L3e in particular occur at high frequencies among African Americans. As with the paternal DNA of African Americans, contributions from other parts of the continent to their maternal gene pool are insignificant.[235]

Racism and social status

Formal political, economic and social discrimination against minorities has been present throughout American history. Leland T. Saito, Associate Professor of Sociology and American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, writes, "Political rights have been circumscribed by race, class and gender since the founding of the United States, when the right to vote was restricted to White men of property. Throughout the history of the United States, race has been used by Whites for legitimizing and creating difference and social, economic and political exclusion."[63]

Although they have gained a greater degree of social equality since the civil rights movement, African Americans have remained stagnant economically, which has hindered their ability to break into the middle class and beyond. As of 2020, the racial wealth gap between Whites and Blacks remains as large as it was in 1968, with the typical net worth of a White household equivalent to that of 11.5 Black households.[236] Despite this, African Americans have increased employment rates and gained representation in the highest levels of American government in the post–civil rights era.[237] However, widespread racism remains an issue that continues to undermine the development of social status.[237][238]

Economically, of all the racially Black ethnic groups on the globe, African Americans are the wealthiest and most successful, with one in every fifty African American families being millionaires.[239] This equates in 2023 to approximately 1.79 million African American millionaires in the United States,[240][241] which is more than the total amount of millionaires in any racially Black country, and many other countries, around the world.

Policing and criminal justice

In the US, which has the largest per-capita prison population in the world, African Americans are overrepresented as the second largest population of prison inmates (38%) in 2023, coming second to Whites who made up 57% of the prison population.[242] According to the National Registry of Exonerations, Blacks are roughly 7.5 times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder in the US than Whites.[243] In 2012, the New York City Police Department detained people more than 500,000 times under the city's stop-and-frisk law. Of the total detained, 55% were African-Americans, while Black people made up 20% of the city's population.[244]

African American males are more likely to be killed by police when compared to other races.[245] This is one of the factors that led to the creation of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013.[246] A historical issue in the US where women have weaponized their White privilege in the country by reporting on Black people, often instigating racial violence,[247][248] difficult White women—who have been given a different name over the centuries by African Americans—calling the police on Black people became widely publicized in 2020.[249][250] According to The Guardian, "The specter of Karen persisted as Black Lives Matter protests and civil unrest spread around the country following Floyd’s murder and reckonings with racism began to roil institutions, toppling careers as well as statues".[251]

Although there is not enough evidence that suggest Black people consume cannabis with greater regularity than Whites do, they have disproportionately higher arrest rates than Whites: in 2010, for example, Blacks were 3.73 times as likely to get arrested for using cannabis than Whites, despite not significantly more frequently being users.[252][253] Even since the legalization of cannabis, there are still more arrests made for Black users than White, wasting taxpayer money, due to many of those cases being abandoned or dropped, with no charges being filed after the trivial, racially-biased arrests.[254][255]

Social issues

After over 50 years, marriage rates for all Americans began to decline while divorce rates and out-of-wedlock births have climbed.[256] These changes have been greatest among African Americans. After more than 70 years of racial parity Black marriage rates began to fall behind Whites.[256] Single-parent households have become common, and according to US census figures released in January 2010, only 38 percent of Black children live with both their parents.[257] In 2021, statistics show that over 80 percent marriages in the African American ethnic group marry within their ethnic group.[258]

The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by the Maryland General Assembly in 1691, criminalizing interracial marriage.[259] In a speech in Charleston, Illinois in 1858, Abraham Lincoln stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people".[260] By the late 1800s, 38 US states had anti-miscegenation statutes.[259] By 1924, the ban on interracial marriage was still in force in 29 states.[259] While interracial marriage had been legal in California since 1948, in 1957 actor Sammy Davis Jr. faced a backlash for his involvement with White actress Kim Novak.[261] Harry Cohn, the president of Columbia Pictures, with whom Novak was under contract, gave in to his concerns that a racist backlash against the relationship could hurt the studio.[261] Davis briefly married Black dancer Loray White in 1958 to protect himself from mob violence.[261] Inebriated at the wedding ceremony, Davis despairingly said to his best friend, Arthur Silber Jr., "Why won't they let me live my life?" The couple never lived together, and commenced divorce proceedings in September 1958.[261] In 1958, officers in Virginia entered the home of Mildred and Richard Loving and dragged them out of bed for living together as an interracial couple, on the basis that "any white person intermarry with a colored person"—or vice versa—each party "shall be guilty of a felony" and face prison terms of five years.[259] In 1967 the law was ruled unconstitutional (via the 14th Amendment adopted in 1868) by the US Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia.[259]

In 2008, Democrats overwhelmingly voted 70% against California Proposition 8, African Americans voted 58% in favor of it while 42% voted against Proposition 8.[262] On May 9, 2012, Barack Obama, the first Black president, became the first US president to support same-sex marriage. Since Obama's endorsement there has been a rapid growth in support for same-sex marriage among African Americans. As of 2012, 59% of African Americans support same-sex marriage, which is higher than support among the national average (53%) and White Americans (50%).[263]

Polls in North Carolina,[264] Pennsylvania,[265] Missouri,[266] Maryland,[267] Ohio,[268] Florida,[269] and Nevada[270] have also shown an increase in support for same sex marriage among African Americans. On November 6, 2012, Maryland, Maine, and Washington all voted for approve of same-sex marriage, along with Minnesota rejecting a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage. Exit polls in Maryland show about 50% of African Americans voted for same-sex marriage, showing a vast evolution among African Americans on the issue and was crucial in helping pass same-sex marriage in Maryland.[271]

Black Americans hold far more conservative opinions on abortion, extramarital sex, and raising children out of wedlock than Democrats as a whole.[272] On financial issues, however, African Americans are in line with Democrats, generally supporting a more progressive tax structure to provide more government spending on social services.[273]

Political legacy

African Americans have fought in every war in the history of the United States.[274]

The gains made by African Americans in the civil rights movement and in the Black Power movement not only obtained certain rights for African Americans but changed American society in far-reaching and fundamentally important ways. Prior to the 1950s, Black Americans in the South were subject to de jure discrimination, or Jim Crow laws. They were often the victims of extreme cruelty and violence, sometimes resulting in deaths: by the post World War II era, African Americans became increasingly discontented with their long-standing inequality. In the words of Martin Luther King Jr., African Americans and their supporters challenged the nation to "rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed that all men are created equal ..."[275]

The civil rights movement marked an enormous change in American social, political, economic and civic life. It brought with it boycotts, sit-ins, nonviolent demonstrations and marches, court battles, bombings and other violence; prompted worldwide media coverage and intense public debate; forged enduring civic, economic and religious alliances; and disrupted and realigned the nation's two major political parties.

Over time, it has changed in fundamental ways the manner in which Blacks and Whites interact with and relate to one another. The movement resulted in the removal of codified, de jure racial segregation and discrimination from American life and law, and heavily influenced other groups and movements in struggles for civil rights and social equality within American society, including the Free Speech Movement, the disabled, the women's movement, and migrant workers. It also inspired the Native American rights movement, and in King's 1964 book Why We Can't Wait he wrote the US "was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race."[276][277]

Media and coverage

Some activists and academics contend that American news media coverage of African American news, concerns, or dilemmas is inadequate,[278][279][280] or that the news media present distorted images of African Americans.[281]

To combat this, Robert L. Johnson founded Black Entertainment Television (BET), a network that targets young African Americans and urban audiences in the United States. Over the years, the network has aired such programming as rap and R&B music videos, urban-oriented movies and television series, and some public affairs programs. On Sunday mornings, BET would broadcast Christian programming; the network would also broadcast non-affiliated Christian programs during the early morning hours daily. According to Viacom, BET is now a global network that reaches households in the United States, Caribbean, Canada, and the United Kingdom.[282] The network has gone on to spawn several spin-off channels, including BET Her (originally launched as BET on Jazz).[283]

Another network targeting African Americans is TV One. TV One is owned by Urban One, founded and controlled by Catherine Hughes. Urban One is one of the nation's largest radio broadcasting companies and the largest African American-owned radio broadcasting company in the United States.[284]

In June 2009, NBC News launched a new website named TheGrio.[285] It is the first African American video news site that focuses on underrepresented stories in existing national news.[286]

Black-owned and oriented media outlets

- The Africa Channel – Dedicated to programming about African culture.

- aspireTV – a digital cable and satellite channel owned by businessman and former basketball player Magic Johnson.

- ATTV – an independent public affairs and educational channel.

- BET Media Group – The most prominent multimedia outlet targeting Afro-Americans.

- Bounce TV – a digital multicast network owned by the E. W. Scripps Company.

- Fox Soul – a digital television and streaming network primarily airing original talk shows and syndicated programming

- Oprah Winfrey Network – a cable and satellite network founded by Oprah Winfrey and jointly owned by Warner Bros. Discovery and Harpo Studios. While not exclusively targeting African Americans, much of its original programming is geared towards a similar demographic.

- Revolt – a music channel and media company founded by Sean "Puff Daddy" Combs.

- Soul of the South Network – a regional broadcast network.

- TheGrio – a digital multicast network focused on news and opinion-based programming.

- TV One – a general entertainment network targeting adults.

- Cleo TV – a sister network targeting millennial and Generation X women

- We TV – Owned by AMC Networks, became slanted towards Black women during the 2010s

Culture

From their earliest presence in North America, African Americans have significantly contributed literature, art, agricultural skills, cuisine, clothing styles, music, language, and social and technological innovation to American culture. The cultivation and use of many agricultural products in the United States, such as yams, peanuts, rice, okra, sorghum, grits, watermelon, indigo dyes, and cotton, can be traced to West African and African American influences. Notable examples include George Washington Carver, who created nearly 500 products from peanuts, sweet potatoes, and pecans.[288] Soul food is a variety of cuisine popular among African Americans. It is closely related to the cuisine of the Southern United States. The descriptive terminology may have originated in the mid-1960s, when soul was a common definer used to describe African American culture (for example, soul music). African Americans were the first peoples in the United States to make fried chicken, along with Scottish immigrants to the South. Although the Scottish had been frying chicken before they emigrated, they lacked the spices and flavor that African Americans had used when preparing the meal. The Scottish American settlers therefore adopted the African American method of seasoning chicken.[289] However, fried chicken was generally a rare meal in the African American community and was usually reserved for special events or celebrations.[290]

Language

African-American English is a variety (dialect, ethnolect, and sociolect) of American English, commonly spoken by urban working-class and largely bi-dialectal middle-class African Americans.[291]