1937 tour of Germany by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor

Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor, and Wallis, Duchess of Windsor, visited Nazi Germany in October 1937. Edward had abdicated the British throne in December 1936, and his brother Albert had become king. Edward had been given the title Duke of Windsor and married Wallis Simpson in June 1937. He appeared to have been sympathetic to Germany in this period and, that September, announced his intention to travel privately to Germany to tour factories. His interests, officially researching the social and economic conditions of the working classes, were against the backdrop of looming war in Europe. The Duke's supporters saw him as a potential peacemaker between Britain and Germany, but the British government refused to sanction such a role, opposed the tour and suspected that the Nazis would use the Duke's presence for propaganda. Prince Edward was keen for his wife, who had been rejected by the British establishment, to experience a state visit as his consort. He promised the government to keep a low profile, and the tour went ahead between 12 and 23 October 1937.

The Duke and the Duchess, who were officially invited to the country by the German Labour Front, were chaperoned for much of their visit by its leader, Robert Ley. The couple visited factories, many of which were producing materiel for the rearmament effort, and the Duke inspected German troops. The Windsors were greeted by the British national anthem and Nazi salutes. They dined with high-ranking Nazis such as Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, and Albert Speer, and had tea with Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden. The Duke had a long private conversation with Hitler, but it is uncertain what they discussed, as the minutes of their meeting were lost during the war. The Duchess took afternoon tea with Hitler's deputy, Rudolf Hess. Hitler was sympathetic to the Windsors and treated the Duchess like royalty.

The British government was unable to affect the course of events and forbade its diplomatic staff in Germany from having any high-level interaction with the Windsors. British popular opinion of the tour was muted, and most people viewed it as in poor taste and disrupting the first year of George's reign. The tour of Germany was intended to have been followed by one of the United States, but Nazi repression of working-class activists in Germany led to a wave of disapproval for the Windsors in the American labour movement, which led to the U.S. visit being cancelled. Modern historians tend to consider the 1937 tour as a reflection of both the Duke's lack of judgment and his disregard for the advice that he received.

Background

[edit]Edward VIII became king after the death of his father, George V, in early 1936.[1] Almost immediately, he announced his intention to marry Wallis Simpson,[2] a twice-divorced American.[3] On political and moral grounds, she was unacceptable as a royal consort to the British government and royal family.[4] As king, Edward was the titular governor of the Church of England, which forbade the divorced from remarrying during the lifetime of their former spouses, and both of Simpson's previous husbands were still alive.[note 1] The proposed marriage was believed by critics to breach Edward's coronation oath,[note 2] and weakened his position as constitutional monarch.[11] Edward knew that if he forced the issue, Stanley Baldwin's government would almost certainly resign en masse.[12]

Edward realised that his family, the government, the Church, and the people would not support the marriage.[13] Thus, in December 1936, he abdicated.[14] His younger brother, the Duke of York, succeeded him as George VI, and Edward was given the title of Duke of Windsor.[15] Edward and Simpson married in France in June the following year,[14] and having honeymooned in Vienna, they returned to Paris and established their headquarters there.[16] Internationally, journalist Andrew Morton stated that the Duke was viewed as:

Modern, progressive, vigorous, and accessible. Even his mock Cockney accent with a touch of American seemed more down-to-earth and unaffected than the disdainful patrician tones of a man like Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. He remained an intriguing international celebrity, his marital turmoil only enhancing the iconic mystery surrounding the man.[17]

Political context

[edit]

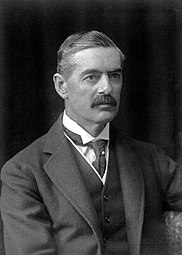

The European political background to the tour was tense. The Spanish Civil War, which had broken out the previous year, upset the balance of power and drew in the Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany.[18][19] Also, Germany was becoming increasingly aggressive and had spent the previous few years rearming. In the United Kingdom, there was a sense of political unease towards the future and an expectation of war[20] although foreign policy remained predicated on appeasement.[21] Baldwin resigned as prime minister in May 1937[22] and was replaced by his deputy, Neville Chamberlain.[23]

Historian Michael Bloch states that although with hindsight, the tour can be viewed as a poor decision, it was not out of place for the time. He notes that "war was still two years away, curiosity about the Nazis was intense, and many respectable people accepted government invitations. It was fashionable to go to Germany and visit Hitler in the mid-thirties just as it was to go to China and visit Mao Tse-tung in the sixties".[24] The former prime minister, David Lloyd George, had visited Germany two years before the Windsors.[25] The leader of the Labour Party, pacifist George Lansbury met with Hitler in April 1937.[26] Also, Lord Halifax, later foreign secretary, visited to do so, at Göring's invitation, the following month.[25] Halifax's trip was "ostensibly ... a social one",[27] but it was also an opportunity for the British government to initiate talks with Hitler, according to modern historian Lois G. Schwoerer.[28] Similarly, Hitler hosted many non-Germans, including Aga Khan III, papal nuncio Cesare Orsenigo, ambassadors, government ministers, and European royals, at his residence in Bavaria, the Berghof.[29]

Royal and governmental view

[edit]George VI is said to have been horrified by his brother's entry into European political affairs at such a delicate time.[note 3] George wrote to Edward's political advisor, Walter Monckton, that the Duke's plan was "a bombshell, and a bad one".[31] George took particular umbrage because on abdication, Edward had said that he intended to avoid public appearances.[32] Royal biographer Sarah Bradford suggests that the visit indicated that Edward had no intention of retiring: rather, he intended to behave independently of the King's and the government's wishes.[33]

Contemporaries were aware of the negative connotations of a trip to Germany at the time. The announcement took everyone by surprise,[34] and those sympathetic to Edward, such as Winston Churchill and Lord Beaverbrook, attempted to dissuade him from going.[16][note 4] The intervention of an old friend of the Duchess, Herman Rogers, against the trip also proved unsuccessful.[35] The government already suspected that Edward had "strong views on his right to intervene in affairs of state", argues historian Keith Middlemas, but its "main fears ... were of indiscretion".[36] The Foreign Office warned the Duke that the Nazis were propaganda experts; the Duke agreed but promised not to speak publicly while he was there.[25] The government, argues historian Deborah Cadbury, was concerned that the Duke would gather a party around him and promote his own personal foreign policy, outside government control.[37]

Edward stated that his intention for the visit as "without any political considerations and merely as an independent observer studying industrial and housing conditions".[38] He said that one could not ignore what was happening in Germany "even though it may not have one's entire approval".[38] The Duke was sympathetic to the cause of improving working conditions.[39]

Historian Frances Donaldson suggests that his views "had caused offence in England because, according to opinion there, such matters were not the concern of the throne".[40] Statements such as that one, scholar Adrian Philips emphasises, were intended to deflect from Edward's public relationship with Simpson.[41]

Political views of the Duke and Duchess

[edit]Edward was an admirer of Germany[42][43] and fluent in its language,[44][45] which the Duke in his memoirs called "the Muttersprache [mother tongue] of many of our relations".[46][note 5] He knew, too, that German blood "flowed strongly in him",[52] and researcher Mark Hichens speculates that Edward's ancestry led him to favour German culture.[53][54][note 6] As Prince of Wales, he had studied at Magdalen College, Oxford, under Hermann Georg Fiedler,[55] and he had toured Germany twice before World War I broke out in 1914.[14] One of his friends, Chips Channon, Conservative MP for Southend West, commented in 1936 that he "is going the dictator way, and is pro-German".[56][57] Simpson was also believed to hold similar views on account of her rejection by the British ruling class,[58] and many within the government suspected her to have spied for Hitler while she lived in Britain[59] though she denied that in her autobiography.[60] The FBI also monitored her throughout the period and concluded that she had Nazi sympathies. It had been rumoured that she and Joachim von Ribbentrop had a sexual relationship during his tenure as German ambassador in London during the mid-1930s.[61][note 7] Albert von Mensdorff-Pouilly-Dietrichstein, a former Austrian ambassador to the UK who was George V's second cousin, believed that both Windsors favoured German fascism as a bulwark against communism in Europe. Edward also, according to the Count, favoured an alliance with Nazi Germany around the time.[65]

Edward himself later contextualised his position in the 1930s as being a reaction to what he termed "the unending scenes of horror"[66] of the First World War. He said that led him to support appeasement with Hitler. The latter is known to have seen the Duke as an ally, believing that as king, Edward would have strengthened Anglo-German relations. Albert Speer later said that Hitler was certain that "through him permanent friendly relations could have been achieved. If he had stayed, everything would have been different."[67][68] The Duke, suggests biographer Anne Sebba, probably wanted to restore the countries' close ties, which had been broken by the First World War.[69] He also wanted to make his new wife the centrepiece of a state visit. Historian Ted Powell suggests that the Duke would have visited any country that would accept his wife on his terms.[70] Edward's equerry, Dudley Forwood, points out that the only possible state visit was to Germany[71] and also suggested that the Duke wished to prove to his wife that he had lost nothing by abdicating.[72]

Overture and organisation

[edit]A tour of Germany had been broached with the Duke before his wedding by French businessman Charles Bedaux, whom Bloch describes as an "enigmatic time and motion tycoon".[16] Edward was agreeable and saw it as a way of raising his profile.[70] By April 1937, Colonel Oscar Solbert had suggested that the Duke take a tour of Germany, which was soon intended to be the first of several planned international tours.[73] Bedaux offered to organise the Duke's side of the arrangements.[74] Solbert had been with Edward on his 1924 tour of the United States and had been impressed by his gravitas and professional demeanour. That led him to suggest to the Duke that he should "head up and consolidate the many and varied peace movements throughout the world".[75] Swedish millionaire Axel Wenner-Gren acted as a go-between for the Duke in the early discussions.[76] Bedaux wrote to Solbert to tell him:[74]

The Duke of Windsor is very much interested in your proposal that he lead a movement so essentially international. We all know that as Prince of Wales and as King, he has always been keenly interested in the lot of the working man and he has not failed to show both his distress and his resolve to alter things whenever he has encountered injustice ... Yet he is not satisfied with the extent of his knowledge. He is determined to continue, with more time at his disposal, his systematic study of this subject and to devote his time to the betterment of the life of the masses ... He believes his is the surest way to peace. For himself he proposes to begin soon with a study of housing and working conditions in many countries ...[74]

— Charles Bedaux to Oscar Solbert, 23 August 1937

The tour of Germany was planned to be a brief visit of 12 days but was to be followed by a longer one of the U.S.[74] The German side of things was organised by Hitler's adjutant,[77] Captain Fritz Wiedemann,[78] with final preparations discussed at the Paris Ritz in late September.[79] The same month, the Duchess wrote to her aunt in Washington that they were planning a trip to observe European working conditions. The Duchess explained that "the Duke is thinking of taking up some sort of work in that direction. The trip is being arranged by Germany's No. 1 gentleman so should be interesting". However she noted that at that stage, it was still only a proposal.[16] Writer Hugo Vickers suggests that Edward believed himself to be able to influence Hitler and avert war in Europe. If that was the case, says Vickers, Edward "severely overestimated his own importance".[58]

Several contacts visited the Windsors at their Paris hotel, Le Meurice, but the nature of their discussions remains unknown, which has encouraged what Cadbury terms colourful theories. One such, for example, by Charles Higham, suggests that on one occasion the Duke received Hitler's deputy, Rudolf Hess, Hess's assistant Martin Bormann, and Hollywood actor Errol Flynn together.[37][note 8] It is more likely, she claims, that the rooftop restaurant meetings involved men such as Wiedemann finalising the itinerary and other minutiae.[37]

Announcement

[edit]

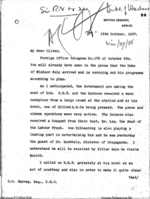

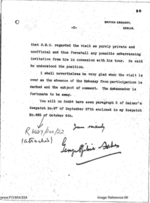

Powell suggests that Edward found the German government's response to be sufficiently sympathetic to proceed without delay.[70] In late September, he received a personal invitation from Dr Robert Ley, the head of the German Labour Front (GLF).[81][note 9] Edward first indicated that he intended to accept in a letter to the British chargé d'affaires in Berlin, George Ogilvie-Forbes, on 20 September.[83] A public announcement followed two weeks later.[84] A telegram to the Foreign Office stated:[16]

In accordance with the Duke of Windsor's message to the world press last June that he would release any information of interest regarding his plans or movements, His Royal Highness makes it known that he and the Duchess of Windsor are visiting Germany and the United States in the near future for the purpose of studying housing and working conditions in these two countries.[16]

Historian Jonathan Petropoulos suggests that the British government knew that it could not prevent what was officially a visit by a private individual.[85] In private, the news angered[84] both Downing Street and Buckingham Palace. The Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, Robert Vansittart, wrote to the King's Private Secretary, Alec Hardinge, to condemn the tour.[84] Hardinge agreed and described it as a "private stunt for publicity purposes".[84] He also reasoned that the premise of the tour was flawed: neither the Duke nor his visit, he said, could "obviously ... bring any benefit to the workers themselves".[84] Ley proposed to hold Nazi rallies at each stop on the Windsors' tour, but the Duke had vetoed it on the grounds that it constituted anti-British propaganda.[86]

11–23 October 1937

[edit]Historian Andrew Roberts suggests that the German government believed that Edward had been forced to abdicate as a result of his pro-German views, which encouraged them to "lay out the red carpet" for him.[31][note 10] On 10 October,[88] the Duke's cousin, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, wrote to him, "dear David![note 11] I hear that you are coming to Germany ... I naturally would be delighted if you could take this opportunity to see me; perhaps I could introduce you to a couple of interesting personalities whom you otherwise wouldn't meet".[89] Hitler and Ribbentrop planned that although the tour was a private rather than state visit, the Windsors, particularly the Duchess,[90] would effectively undertake a royal progress.[91] That was first demonstrated on their arrival,[92] early Monday morning,[93] at Berlin's Friedrichstraße station on 11 October. Scholar Susanna de Vries describes how the Duchess "covered in jewels ... did her best to look suitably royal",[92] dressed in royal blue. They were greeted by Ley, who kissed her hand and called her "Your Highness".[94][note 12] With Ley was a welcoming delegation including Ribbentrop and the deputy to the Gauleiter of Berlin, Artur Görlitzer. Also waiting was the British Embassy's Third Secretary[96] to present a letter informing the Duke that the Embassy would not be available to assist him or his wife formally in the course of their visit.[34] Ogilvie-Forbes later visited the Duke in his hotel to pay the personal respects that he had been unable to pay him in public.[97][note 13]

A welcoming crowd of approximately 2,000 lined the streets outside the station. The German media had set great store by the Windsors' visit from the beginning.[98] As the Windsors were leaving, the crowd surged forward, and a crush ensued. That, noted Cadbury, destroyed the "majestic air" of the reception that Ley had organised.[99] With few of the crowd having seen them, the couple were driven away at high-speed in their Mercedes, to their hotel, the Kaiserhof.[100]

Pathé caught the moment they emerged from the station into a large crowd that had gathered determined to see this unique couple: a king who had thrown away the greatest throne in the world for love, and the woman herself, who must possess some magical quality. Dr Ley, the head of the German delegation, wearing his brown Nazi uniform and for once not drunk, delighted them both by deferring to her as 'Her Royal Highness'.[94]

— Deborah Cadbury

The couple were treated like royalty[101] by the German aristocracy, which "would bow and curtsy towards [the Duchess], and she was treated with all the dignity and status that the Duke always wanted".[101]

On their first night in Berlin, they joined Ribbentrop for dinner at Horcher. The night was attended by Speer with whom they discussed classical music,[35] and Magda and Joseph Goebbels,[102] who were Germany's de facto first lady[103] and Reich Minister of Propaganda respectively.[104] After their meeting, Goebbels wrote in his diary that "the duke is wonderful—a nice, sympathetic fellow who is open and clear and with a healthy understanding of people ... It's a shame he is no longer king. With him we would have entered into an alliance."[102] The Duchess did not reciprocate, describing him as "a tiny, wispy gnome with an enormous skull", but Magda, she continued, was "the prettiest woman I saw in Germany".[45] The Windsors dined with his cousin the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on the 19th.[88] The Duke later recalled that the dinner was attended by over 100 guests, many whom he had "hobnobbed" with at both his father's jubilee and then his funeral.[89][note 14]

Itinerary

[edit]The Berlin correspondent of the British Observer newspaper, reporting the couple's arrival, wrote that they could look forward to a "heavy programme" of events.[93] The couple and their entourage, which included the Duke's cousin Prince Philipp von Hessen,[107] travelled around Germany on Hitler's personal train, the Führersonderzug,[108][109] while their telephones were bugged by Prince Christoph of Hesse on the orders of Reichsstatthalter Hermann Göring to keep the Nazi leadership informed of the Windsors' private opinions.[89] The German government was funding the visit,[89] which modern historian John Vincent suggests allowed them to choreograph it.[83] Hichens, too, notes that the Windsors "saw only what the Nazis wanted them to see, and the Duke saw what he wanted to see turning a blind eye on the horrors of Nazidom".[110] For example, according to Morton, they visited a barracks of apparently-empty concrete buildings that they later realised had been a concentration camp. When the Duke enquired as to their purpose, Ley replied, wrote Forwood later, " 'it is where they store the cold meat.' In a horrible sense that was true."[111]

Although the couple were in Germany at Ley's personal invitation,[112][113] he was a poor host. Bloch describes him as coarse, "addicted to alcohol [and] high-speed driving",[25][note 15] and risqué jokes.[116] Hichens views Ley as "loud-mouthed", brutal and a "particularly odious Nazi thug."[117] On one journey, he was drunk at the wheel of the Windsors' Mercedes while he was driving at speed and crashed them into the gates of the Munich factory that they were visiting.[108][118] One of Ley's aides, Hans Sopple, later described events, saying Ley "drove the car through the locked gates and then raced up and down at full speed between the barracks, scaring hell out of the workers and nearly running over several. The next day Hitler told Göring to take over the Duke's visit before Ley killed him."[113] That was not, comments Morton, "at all what the Duke had in mind when he described the nature of a royal tour to his wife".[119]

Bloch describes the couple's itinerary as an "exhausting" series of visits to industrial and housing areas.[25] A letter from the Duchess confirms that although the tour was interesting, it involved walking "miles a day through factories",[120] including one that produced lightbulbs.[68] Among other sights, they saw a winter relief centre, a Wagnerian opera in a workers' concert hall,[100][68] and inspected a Pomeranian SS squadron with the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, Hitler's personal bodyguard.[121] The Duchess did not accompany her husband everywhere; he visited the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft at Untertürkheim alone, which was intended to showcase German precision engineering to the Duke, and while there he met British racing driver Richard Seaman, who had signed for the Mercedes-Benz team earlier in the year.[68]

On 14 October,[100] the Duke and the Duchess visited Göring at his jagdschloss in Carinhall,[102] where they saw his miniature railway.[122] There, Hitler's deputy gave them high tea, followed by a tour of his large art collection[100] and gymnasium, where, although dressed in full uniform and decorations, he demonstrated his massage machine.[123] The three conversed in Göring's study, where Edward noticed a new, official map of Nazi Germany on the wall. Reflecting the party's Anschluss policy, Austria was shown as annexed to Germany. Cadbury quotes Simpson: "Göring's face wrinkled with amusement ... The Austrians would want to be part of the Reich", he had said. Simpson noted that "the moment passed, the statement left unchallenged" by the Duke.[100][note 16]

They visited an Academy for Youth Leadership, where they observed the training of Hitler Youth members. On an inspection of the Krupp factory in Essen, production of tanks and U-boats had already begun.[100] On each visit, the couple were presented with enthusiastic workers keen to extol their working conditions to the Duke. He, in turn, was at his most charming, says Hichens. On one occasion, he joined a session of rowdy drinking songs in a staff beer garden,[117] where he wore a false moustache and played skittles.[72] The couple were regularly greeted with the Nazi salute, which they sometimes reciprocated[100] (that was not unusual, and most visitors to Germany, including sports teams, then made the salute).[125] The couple were welcomed at each venue by both the German and the British national anthems.[100] The Nazis, researcher Peter Allen finds, knew the Duchess to have a keen interest in china, and as such, they included a trip to the Meissen porcelain works. Allen suggests that this demonstrated a policy of pleasing the Duke through his wife.[126] On a visit to one of Ley's GLF meetings Edward made a speech, telling the assembly:[127]

I have travelled the world and my upbringing has made me familiar with the great achievements of mankind, but that which I have seen in Germany, I had hitherto believed to be impossible. It cannot be grasped, and is a miracle; one can only begin to understand it when one realizes that behind it all is one man and one will.[127]

Simpson, meanwhile, notes Morton, maintained the fiction in her letters to her friends and family that they were merely sightseeing.[128]

Meeting Hitler

[edit]The tour culminated on 22 October, when they met Hitler[102] at the Berghof.[98] It is possible that the meeting was a last-minute addition to their itinerary, as they were supposedly told of it only the previous day, although Allen suggests that this was unlikely, as Hitler had expressed a wish to meet the Duke.[130]

The Duke and the Duchess had to wait before Hitler was ready to see them[25] although, notes Vickers, he was in a genial mood when he did.[131] The two men had an hour-long discussion, with Hitler doing most of the talking.[25][101] The Duke is known to have encouraged Hitler in Germany's desired territorial expansion into Central and Eastern Europe. The minutes of the meeting appear to have been lost, presumably destroyed during the war.[92] The Duchess did not join her husband but instead had tea with Hess.[132] General Ernst Wilhelm Bohle[133] acted as her interpreter. A friend of the Windsors, French millionaire Paul-Louis Weiller, later said that the Duchess had organised the meeting with Hitler and that being excluded from it had angered her.[58] At the end of their visit, the three had tea together.[85] Hitler's partner, Eva Braun, was not present: whenever he entertained guests of high rank, she had to stay in her bedroom until they had left.[134] The Windsors made a good impression on Hitler, suggests Hichens;[117] the Duchess later wrote how she was both "fascinated and repelled" by Hitler.[120] Hitler, comments historian Philip Ziegler, "mildly irritated the Duke by insisting on using an interpreter rather than speaking directly to him in German".[135] Interpreter Paul Schmidt later recalled the meeting:[25]

Hitler was evidently making an effort to be as amicable as possible towards the Duke, whom he regarded as Germany's friend, having especially in mind a speech the Duke had made some years before, extending the hand of friendship to Germany's ex-servicemen's associations. In these conversations, there was, so far as I could see, nothing whatever to indicate whether the Duke of Windsor really sympathised with the ideology and practices of the Third Reich, as Hitler seemed to assume he did. Apart from some appreciative words for the measures taken in Germany in the field of social welfare, the Duke did not discuss political questions.[25]

Forwood disagrees with Schmidt's recollection and says that the Duke raised criticisms of Nazi social policy. Forwood also says that at the same time, Forwood accused Schmidt of mistranslating for Hitler and that Forwood interjected "Falschübersetzt!" or "wrongly translated!"[120] The Duke departed, he believed, under the impression that Hitler was a pacifist.[58] An observer describes how they returned to their car and were escorted by their host:[85]

The Duchess was visibly impressed with the Führer's personality, and he apparently indicated that they had become fast friends by giving her an affectionate farewell. [Hitler] took both their hands in his saying a long goodbye, after which he stiffened to a rigid Nazi salute that the Duke returned.[85]

Historian Volker Ullrich argues that Hitler seems to have been flattered that the Windsors wanted to see him. Weidemann later said that he had rarely seen Hitler "so relaxed and animated as during that visit".[136] The meeting concerned the British government since it appeared to be almost an informal summit.[137] Three days earlier, Hitler had been telephoned by future British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, regarding Germany's expansionist policies. Halifax had pressed the benefits of a mutual understanding between their two countries. The Windsors' visit soon after, says Sebba, probably encouraged Hitler to see Edward as an ally.[138] Edward later said that he had thought Hitler was "a somewhat ridiculous figure, with his theatrical posturings and his bombastic pretensions", and he denied to his wife that he and Hitler had discussed politics at all. The Duke's interpreter, Dudley Forwood, also put down his different recollection of what was said by writing how "my Master said to Hitler the Germans and the British races are one, they should always be one. They are of Hun origin."[139]

The Duke and Duchess spent the last night of their tour back in Munich, where they stayed at the Vier Jahreszeiten Hotel; the Duke received some personal guests. One of them was a Kreisleiter of the Nazi Party, who had previously been Master of Ceremonies for Grand Duke Adolphus Frederick VI of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a personal friend of the Duke's father.[85] The main event was a dinner given by Rudolf and Ilse Hess and attended by high-ranking Nazi officials. Petropoulos comments that although there are no records of what may have been discussed at the dinner, "it is striking that the Duke and Hess, both future advocates of a negotiated peace, had the opportunity to spend the evening together and review the Windsors' tour".[85] Ilse Hess later told how at one point, the Duke and her husband had been gone for over an hour. She found them in an upstairs games room. There, Hess had a large collection of model ships, and he and the Duke were "excitedly" re-enacting a World War I naval battle.[140]

Reactions

[edit]The British government vainly tried to control public relations during the visit.[85] Cadbury notes how a former English king "turning up in ... Berlin was an unexpected bonus" for German diplomacy.[141] German newspaper Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung boasted about the number and the quality of the people who wanted to see the Nazis' social programme first hand, and it wrote that "the Duke of Windsor, too, has come to convince himself personally of the energy with which the new Germany has tackled her social problems".[93] The German government took advantage as soon as the Duke and Duchess departed. Ogilvie-Forbes reported that Ley had already announced that Edward had praised Hitler's leadership.[142] Hitler subsequently asserted that Simpson, in his opinion, would have been a good queen.[143] Hitler believed Edward understood the Führerprinzip,[144] and that he was a man with whom the Nazis could work. The tour may have given rise to later suspicions that in the event of a successful outcome to Operation Sea Lion, a German invasion of Britain, the Duke would have been appointed as a puppet king.[145] In his diary, the Earl of Crawford summed up the British establishment's views on the Duke:[146]

He had put himself hopelessly in the wrong by starting his visit with a preliminary tour in Germany where he was, of course, photographed fraternizing with the Nazi, the Anti-Trade Unionist and the Jewbaiter. Poor little man. He has no sense of his own and no friends with any sense to advise him. I hope this will give him a sharp and salutary lesson.[146]

— The Earl of Crawford

Similarly, diplomat and soldier Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart noted in his diary that he expected Edward to return sooner rather than later as "a social-equalising king, inaugurate an English form of fascism and an alliance with Germany".[72] To the British ruling class, comments Morton, the Windsors' "farrago was greeted with undisguised glee".[146] On the other side of the parliamentary divide, the Labour Party MP Herbert Morrison (leader of the London County Council) wrote that "if the Duke wants to study social problems he had far better quietly read books and get advice in private, rather than put his foot in it in this way".[58] The Times reported how "His Royal Highness acknowledges with smiles and the National Socialist salute the greetings of the crowds gathered at his hotel and elsewhere during the day".[121] The Daily Express, meanwhile, stated that Edward had received "the kind of reception that only the old kings of Bavaria could expect".[147] The reaction in Germany, according to the British attaché in Leipzig, was that the tour had demonstrated the Duke's "strong pro-fascist sympathies". In the Soviet Union, the view was that the British royal family had "warm feelings" for Germany.[148]

Historiography

[edit]The most positive aspect of the visit, comments Powell, "was that it had been well-organised, albeit for the benefits of the hosts".[90] Philips calls the tour "an embarrassment at best, and at worse, glaring proof of his complete lack of judgement".[149] Piers Brendon describes it as "the worst blunder of his career".[150] Roberts calls the tour "fantastically ill-judged",[31] and Bloch notes that the Duke's political contemporaries were all in agreement that starting the tour in Nazi Germany at such a time was nothing short of "disastrous".[151][152] Scholar Julia Boyd, comparing the meeting with Hitler with others that had taken place—the Aga Khan, for example—notes that while attracting a great deal of comment, they "could not compete with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor ... in terms of celebrity and sheer inappropriateness".[93]

Sebba explains Edward's lack of judgement by the fact that while he had been able to call on a wide spectrum of counsel as Prince of Wales, he now had only his wife and acquaintances.[55] Powell, similarly, believes that Edward's reputation "was at the mercy of unscrupulous strangers".[90] Ziegler, conversely, suggests that while the trip may have been "ill-advised and ill-timed ... [it was] not a crime".[138] Vickers, similarly, suggests that while the tour may have helped fuel the theory that the Duke was a Nazi, "he was no such thing. But he was naive, and having been brought up with people to advise him all his life until December 1936 he was hardly competent or equipped to deal with men like Hitler. Nor should he have undertaken this trip independently."[58]

According to Sebba, Edward promised to refrain from making speeches so that his words could not be used against him by critics.[139] Some scholars, such as Bradford, believe the visit to be directly the result of "pro-German and even more pro-Nazi" views.[153] German people who witnessed the Duke on tour, suggests Morton, did not see him "either publicly or privately, as a collaborator, appeaser or traitor to his country. Far from it."[154] Scholar Gerwin Strobl agrees and writes:[155]

When the Nazis were dealing with a useful fool, they could never quite disguise an element of contempt in their language; when they met a rogue, their words betray a shared contempt for others. There is nothing of this in the descriptions of the Duke's conversations in Berlin or the later wartime recollections of his actions and opinions. Instead, there is something one comes across only very rarely in Nazi utterances: genuine respect; the respect felt for an equal."[155]

Aftermath

[edit]The Windsors' German tour made little impact on the British public, and the main criticism seems to have been the failure to keep the low profile that he had promised. Churchill, for example, wrote to the Duke to imply that there had been little notice taken of the Nazi aspect and that he was "glad it all passed off with such distinction and success".[38] The new prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, disagreed with the tour and privately worked against it, but, comments historian of Nazi Germany Karina Urbach, "as a convinced monarchist [he] did everything to keep the institution intact".[105]

In 1966, the Duke described his memories of meeting Hitler, who had, Edward said, "made me realize that Red Russia [sic] was the only enemy and that Great Britain and all of Europe had an interest in encouraging Germany to march against the east and to crush communism once and for all ... I thought that we ourselves would be able to watch as the Nazis and the Reds would fight each other".[156][note 17] His equerry, Forwood, said something similar in his memoirs:[158]

Whereas the Duke, Duchess and I had no idea that the Germans were or would be committing mass murder on the Jews, we were none of us averse to Hitler politically. We felt that the Nazi regime was a more appropriate government than the Weimar Republic, which had been extremely socialist.[158]

Later events

[edit]The Windsors returned to Paris on 24 October, with a fortnight to prepare for the tour of the United States.[38] The week after the Windsors left Munich, the Nazis executed two KPD organisers and labour leaders: Adolf Rembte and Robert Stamm. They were widely admired in the American labour movement for their trade union and anti-Nazi activity; their deaths swung popular opinion against the Duke and the Duchess.[159] Labour unions campaigned against the tour, particularly in the Duchess's hometown of Baltimore, Maryland. Unions said that they would not support the Windsors' visit and called them either "emissaries of a dictatorship or uninformed sentimentalists".[160]

Bedaux, who, Vincent suggests, intended to use the Duke to regain possession of his confiscated German business,[83] was irreparably damaged by the fallout from the Windsors' tour. In 1938, his German businesses were confiscated by the Nazis permanently. His reputation also suffered in America, where his operations were forcibly taken over by a U.S.-based subordinate.[161][note 18] The Duke's public connection to Bedaux, combined with the bad publicity, persuaded Edward to cancel the tour.[163] The New York Times reported on 23 October that in its view, the German tour, "demonstrated adequately that the Abdication did rob Germany of a firm friend, if not indeed a devoted admirer, on the British throne. He has lent himself, perhaps unconsciously, but easily to National Socialist propaganda."[164] Another correspondent wrote that "the poor fellow must have very little discretion and must be very badly advised. His going to Germany and hobnobbing with Hitler and Ley just before visiting America was enough to enrage every liberal organization in the country."[165]

The American trip had been intended to demonstrate the Duke's leadership qualities, and its cancellation was sufficiently traumatic to induce him to retire temporarily from public life.[166] U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote a conciliatory letter to the Windsors that expressed hope that the tour would eventually go ahead.[167] After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, says Bloch, the British government removed the Windsors from Europe for the war's duration. The Duke was appointed governor of the Bahamas. Churchill wrote to Roosevelt in July 1940:[168]

The position of the Duke of Windsor in recent months has been causing His Majesty and His Majesty's Government some embarrassment as though his loyalties are unimpeachable there is always a backwash of Nazi intrigue which seeks to make trouble about him now that the greater part of the continent is in enemy hands. There are personal and family difficulties about his return to this country. In all the circumstances it was felt that an appointment abroad might appeal to him, and the Prime Minister has with His Majesty's cordial approval offered him the Governorship of the Bahamas. His Royal Highness has intimated that he will accept the appointment.[169]

The Duchess called the Bahamas "the St Helena of the 1940s" for them.[169][170][note 19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ She had married Earl Winfield Spencer Jr. in 1916; they divorced in 1927.[5][6] She then married Ernest Simpson the following year; they divorced in May 1937.[7][8] Spencer and Simpson did not die until 1950 and 1958, respectively.[9]

- ^ The legal historian Graeme Watts notes that officially, Edward never took his coronation oath, but he "gave royal assent to Acts throughout his 325-day reign, including the Act which ended it", and that "taking the oath is neither a prerequisite to the accession to the Crown nor to provision of the royal assent".[10]

- ^ Politically, the late 1930s became increasingly tense in Europe, and an ongoing arms race between the major powers reduced their political room to manoeuvre.[30]

- ^ Beaverbrook tried to persuade Windsor to make only the US tour.[34]

- ^ Windsor's great-grandfather Prince Albert was German,[47] and his great-grandmother Queen Victoria was the daughter of a German princess; further, writes Petropoulos, "the Germanness of the British Royals dissipated very slowly".[48] The family's official name was Saxe-Coburg Gotha, which caused acute publicity problems during the First World War.[49] The crisis came to a head in 1916, when London was bombed by a new German bomber called the Gotha;[50] the next year, George V changed the name to the "thoroughly British" Windsor.[51]

- ^ He was less so of its people of whom he said that "the Germans as a race ... are fat, stolid, unsympathetic, intensely military, and all the men have huge cigars sticking out of their faces at all times".[53]

- ^ Those records were released in 2002[62] although Karina Urbach notes that they contain solely-unsubstantiated rumours and some that are very wild.[63] Middlemas stated that on the contrary, she disliked von Ribbentrop.[64]

- ^ Higham states that British Intelligence files back this story, but Cadbury notes that they have not so far surfaced in the archives.[37] Higham's works have been criticised by commentators, with his generally-unauthorised celebrity biographies earning him a description as "the most unreliable writer on Hollywood politics".[80]

- ^ Ley was an acquaintance of Bedaux, and they worked together throughout the 1930s in various enterprises of Bedaux's that had to run under Nazi oversight.[82]

- ^ Hitler had been encouraged in that belief by von Ribbentrop, Tim Bouverie determines, who told him that the abdication "constituted a plot by the British Government to rid itself of a pro-German monarch".[87]

- ^ Windsor's full birth name was Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, and he was commonly addressed by the last of his names by his family circle.[1]

- ^ The letters patent, published in the London Gazette just before the couples' marriage, and known as the Depriving Act of 1937, explicitly stated that the title of Royal Highness, which conveyed precedence, could be used by the Duke but not the Duchess.[95]

- ^ British diplomatic missions in Germany and the United States were "forbidden to put him up in the house, or to give him a dinner, though they may give him a bite of luncheon, or to present him officially to anyone, or to accept invitations from him, except for a bite of luncheon".[84]

- ^ The Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Coburg were members of the NSDAP and had maintained contact with Windsor's brother, the Duke of Kent, who was also a "useful ally" and "equally anti-French", Ludwig of Hesse wrote.[105] Deborah Cadbury suggests that Hitler first learned of Edward's German sympathies in 1936. His cousin, Charles Edward of Saxe-Coburg, was spying for Hitler in London, and learned much from Edward, says Cadbury.[106]

- ^ Ley was a personal practitioner of schrecklichkeit,[97] and, according to the physicist Kurt Mendelssohn, a "habitual drunkard", who had lost jobs on that account before.[114] Peter Allen comments that Ley "spoke with such a naturally slurred speech that it was said to be difficult to tell whether he was drunk or not".[82] The Duchess later described Ley as "a drunkard, a fanatic, quarrelsome, a four-flusher [an empty boaster]".[115]

- ^ The annexation of Austria took place almost six months to the day later, on 12 March 1938.[124]

- ^ In those aspirations, the Duke was in the company of a large swathe of the British ruling class since the same view was taken by Lloyd George and Lord Halifax, aristocrats such as Lord and Lady Astor and the rest of the Cliveden Set, as well as economists like Montagu Norman, the Governor of the Bank of England.[157]

- ^ Bedaux was already unpopular in America for his known close associations with the Nazis, and during the war, an aide to General Eisenhower, Harry C. Butcher, believed him to be a spy.[162]

- ^ The island of St Helena, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, was the site of Napoleon's final exile.[171]

References

[edit]| Note (electronic editions only) |

|---|

| ch. = chapter§ = paragraph |

- ^ a b Adams 1993, p. 35.

- ^ Beaverbrook 1966, pp. 28–33.

- ^ Sebba 2013, ch.7 §12.

- ^ Ziegler 1991, pp. 305–307.

- ^ Sebba 2013, ch.1 §50.

- ^ Bloch 1996, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Bloch 1996, pp. 82, 92.

- ^ Sebba 2013, pp. 62–67.

- ^ Hamilton 1986, p. 51.

- ^ Watt 2017, p. 336.

- ^ Beaverbrook 1966, pp. 39–44, 122.

- ^ Perkins 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Ziegler 1991, p. 236; Howarth 1987, p. 62; Bradford 2013, p. 241; Pope-Hennessy 1959, p. 574.

- ^ a b c Matthew 2004.

- ^ Taylor 1992, pp. 401–403.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloch 1988, p. 112.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §14.

- ^ Taliaferro, Ripsman & Lobell 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Buchanan 2014, p. 55.

- ^ Merriman 1996, p. 1202.

- ^ McDonough 1998, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Laybourn 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Laybourn 2001, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Bloch 1988, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bloch 1988, p. 113.

- ^ Ascher 2012, p. 202.

- ^ Gilbert 1982, p. 210.

- ^ Schwoerer 1970, pp. 354, 374.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 127.

- ^ Kershaw 2015, pp. 321–322.

- ^ a b c Roberts 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Cadbury 2015, p. 51.

- ^ Bradford 2013, p. 427.

- ^ a b c Allen 1984, p. 102.

- ^ a b Morton 2018, p. 252.

- ^ Middlemas 1969, p. 979.

- ^ a b c d Cadbury 2015, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d Bloch 1988, p. 117.

- ^ Middlemas 1969, p. 996.

- ^ Donaldson 1974, p. 353.

- ^ Phillips 2016, ch.8 §7.

- ^ Hichens 2016, ch.1 §8.

- ^ Hichens 2016, ch.5 §8.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 41.

- ^ a b Bryan & Murphy 1979, p. 391.

- ^ Windsor 1951, p. 41.

- ^ Chadwick 1998, p. 4.

- ^ Petropoulos 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Winter & Kochman 1990, p. 173.

- ^ West 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Windsor 1951, p. 98.

- ^ a b Hichens 2016, ch.1 §12.

- ^ Bryan & Murphy 1979, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b Sebba 2013, ch.11 §12.

- ^ Brendon 2016, ch.3 §8.

- ^ Marr 2009, p. 338.

- ^ a b c d e f Vickers 2011, p. 322.

- ^ ODNB 2004.

- ^ Higham 2004, p. 203.

- ^ Evans & Hencke 2002.

- ^ Beschloss 2002, p. 135.

- ^ Urbach 2015, p. 213.

- ^ Middlemas 1969, p. 980.

- ^ Rose 1983, p. 391.

- ^ Windsor 1951, p. 122.

- ^ Speer 1970, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2020, p. 230.

- ^ Sebba 2013, ch.11 §10.

- ^ a b c Powell 2018, p. 227.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §4.

- ^ a b c Boyd 2018, ch.14 §29.

- ^ Bloch 1988, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c d Bloch 1988, p. 110.

- ^ Bloch 1988, p. 109.

- ^ Bloch 1983, p. 155.

- ^ Bloch 1988, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.11 §39.

- ^ Morton 2018, p. 251.

- ^ Meyers 1998, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Cadbury 2015, pp. 48, 54.

- ^ a b Allen 1984, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Vincent 1984, p. 616.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloch 1988, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e f g Petropoulos 2006, p. 209.

- ^ Bryan & Murphy 1979, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Bouverie 2019, p. 118.

- ^ a b Petropoulos 2006, p. 434.

- ^ a b c d Petropoulos 2006, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Powell 2018, p. 228.

- ^ Brendon 2016, ch.5 §5.

- ^ a b c de Vries 2012, ch.9 §62.

- ^ a b c d Boyd 2018, ch.14 §28.

- ^ a b Cadbury 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Martin 1973, p. 326.

- ^ Bryan & Murphy 1979, pp. 389–390.

- ^ a b Bryan & Murphy 1979, p. 390.

- ^ a b Donaldson 1974, pp. 331–332.

- ^ Cadbury 2015, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cadbury 2015, p. 55.

- ^ a b c BBC News 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Petropoulos 2006, p. 208.

- ^ Meissner 1980, ch.1 §3.

- ^ Manvell & Fraenkel 2010, p. 121.

- ^ a b Urbach 2015, p. 192.

- ^ Cadbury 2015, pp. 53, 228.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.10 §64.

- ^ a b Brendon 2016, ch.5 §7.

- ^ Lepage 2017, p. 149.

- ^ Hichens 2016, ch.8 §30.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §23.

- ^ Time-Life 1990, p. 63.

- ^ a b Smelser 1988, p. 114.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1973, p. 221.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §24.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §22.

- ^ a b c Hichens 2016, ch.8 §31.

- ^ Evans 2005, pp. 463–464.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §30.

- ^ a b c Bloch 1988, p. 114.

- ^ a b Allen 1984, p. 104.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §19.

- ^ Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, ch.5 §72.

- ^ Brook-Shepherd 1963, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Simpson 2016, p. 62.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 107.

- ^ a b Allen 1984, p. 106.

- ^ Morton 2018, p. 253.

- ^ TNA 1937.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 108.

- ^ Vickers 2011, p. 616.

- ^ Sebba 2013, ch.11 §19.

- ^ Sereny 2016, p. 242.

- ^ Sigmund 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Ziegler 1991, p. 338.

- ^ Ullrich 2016, ch.18 §64.

- ^ Bradford 2013, p. 426.

- ^ a b Sebba 2013, ch.11 §15.

- ^ a b Sebba 2013, ch.11 §16.

- ^ Wyllie 2019, ch.7 §46.

- ^ Cadbury 2015, p. 53.

- ^ Petropoulos 2006, p. 210.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §31.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 97.

- ^ Doerries 2003, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Morton 2015, ch.8 §55.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 110.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §36.

- ^ Phillips 2016, Afterword §3.

- ^ Brendon 2016, ch.5 §6.

- ^ Bloch 1988, p. 156.

- ^ Bloch 1983, p. 39 n.3.

- ^ Bradford 2013, p. 433.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §15.

- ^ a b Strobl 2000, p. 109.

- ^ Pauwels 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Pauwels 2015, p. 46.

- ^ a b Morton 2015, ch.8 §37.

- ^ Bloch 1988, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 113.

- ^ Bloch 1988, p. 120.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 99.

- ^ Bloch 1988, p. 119.

- ^ Allen 1984, p. 111.

- ^ Mitchell 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Bloch 1983, p. 156.

- ^ Morton 2015, ch.8 §56.

- ^ Bloch 1983, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Bloch 1983, p. 94.

- ^ Powell 2018, p. 232.

- ^ Unwin 2010, p. 62.

Sources

[edit]- Adams, R. J. Q. (1993). British Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Appeasement, 1935–39. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-80472-101-1.

- Allen, P. (1984). The Windsor Secret: New Revelations of the Nazi Connection. New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-81282-975-4.

- Ascher (2012). Was Hitler a Riddle?: Western Democracies and National Socialism. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-80478-459-7.

- BBC News (10 March 2016). "When the Duke of Windsor met Adolf Hitler". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Beaverbrook, M. A. (1966), Taylor, A. J. P. (ed.), The Abdication of King Edward VIII, London: Hamish Hamilton, OCLC 958201195

- Beschloss, M. R. (2002). The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-74324-454-1.

- Bloch, M. (1983). The Duke of Windsor's War (1st American ed.). New York: Coward, McCann. ISBN 978-0-69811-177-6.

- Bloch, M. (1988). The Secret File of the Duke of Windsor. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-34900-108-1.

- Bloch, M. (1996). The Duchess of Windsor. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-29783-590-5.

- Bouverie, T. (2019). Appeasing Hitler: Chamberlain, Churchill and the Road to War. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-47354-775-9.

- Boyd, J. (2018). Travellers in the Third Reich: The Rise of Fascism Through the Eyes of Everyday People. New York: Pegasus. ISBN 978-1-78396-381-2.

- Bradford, S. (2013). George VI: The Dutiful King (electronic ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-24196-823-9.

- Brendon, P. (2016). Edward VIII (Penguin Monarchs): The Uncrowned King (electronic ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-24119-642-7.

- Brook-Shepherd, G. (1963). Anschluss: The Rape of Austria. London: Palgrave Macmillan. OCLC 246148103.

- Bryan, J. M.; Murphy, C. J. V. (1979). The Windsor Story. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-68803-553-2.

- Buchanan, A. (2014). American Grand Strategy in the Mediterranean during World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10704-414-2.

- Cadbury, D. (2015). Princes at War: The British Royal Family's Private Battle in the Second World War (electronic ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-40884-509-7.

- Chadwick, O. (1998). Prince Albert and the University: The Prince Albert Sesquicentennial Lecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52163-756-5.

- de Vries, S. (2012). Royal Mistresses of the House of Hanover-Windsor: Secrets, Scandals and Betrayals (electronic ed.). Melbourne: Pirgos Press. ISBN 978-1-74298-269-4.

- Doerries, R. R., ed. (2003). Hitler's Last Chief of Foreign Intelligence: Allied Interrogations of Walter Schellenberg. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13577-289-5.

- Donaldson, Frances (1974). Edward VIII. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. OCLC 251334013.

- Evans, R. J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power, 1933–1939: How the Nazis Won Over the Hearts and Minds of a Nation (electronic ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-71819-681-3.

- Evans, R. J.; Hencke, D. (29 June 2002). "Wallis Simpson, the Nazi Minister, the Telltale Monk and an FBI Plot". The Guardian. OCLC 819004900. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Gilbert, M. (1982). Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-39531-869-0.

- Hamilton, A. (1986). The Royal Handbook. London: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13783-358-0.

- Higham, C. (2004). Mrs Simpson: Secret Lives of the Duchess of Windsor. London: Pan. ISBN 978-0-33042-678-7.

- Hichens, M. (2016). Abdication: The Rise and Fall of Edward VIII (electronic ed.). Kibworth: Book Guild Publishing. ISBN 978-1-91132-041-8.

- Howarth, P. (1987). George VI: A New Biography. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09171-000-2.

- Kershaw, I. (2015). To Hell and Back: Europe, 1914–1949. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-24118-715-9.

- Laybourn, K. (2001). British Political Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-043-7.

- Lepage, J-D. G. G. (2017). Military Trains and Railways: An Illustrated History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-47666-760-7.

- Manvell, R.; Fraenkel, H. (2010) [1960]. Doctor Goebbels: His Life and Death. New York: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-61608-029-7.

- Manvell, R.; Fraenkel, H. (2011) [1962]. Goering: The Rise and Fall of the Notorious Nazi Leader. London: Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-600-2.

- Meissner, H. (1980) [1978]. Magda Goebbels: The First Lady of the Third Reich (electronic ed.). New York: The Dial Press. ISBN 978-0-80376-212-1.

- Marr, A. (2009). The Making of Modern Britain. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23074-524-7.

- Martin, R. G. (1973). The Woman He Loved. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-67121-810-2.

- Matthew, H. (2004). "Edward VIII [Afterwards Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor] (1894–1972), King of Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Dominions Beyond the Seas, and Emperor of India". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- McDonough, F. (1998). Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement, and the British Road to War. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71904-832-6.

- Mendelssohn, K. (1973). The World of Walther Nernst: The Rise and Fall of German Science 1864–1941. London: Macmillan. OCLC 716850690.

- Merriman, J. M. (1996). A History of Modern Europe. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-39396-888-0.

- Meyers, J. (1998). Gary Cooper: American Hero. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-6881-549-43.

- Middlemas, K. (1969). Baldwin: A Biography. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. OCLC 905243305.

- Mitchell, A. H. (2007). Hitler's Mountain: The Führer, Obersalzberg and the American Occupation of Berchtesgaden. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78642-458-0.

- Morton, A. (2015). 17 Carnations: The Windsors, the Nazis and the Cover-Up (electronic ed.). New York: Hachette. ISBN 978-1-78243-465-8.

- Morton, A. (2018). Wallis in Love: The Untold True Passion of the Duchess of Windsor (electronic ed.). New York: Hachette. ISBN 978-1-78243-723-9.

- Pauwels, J. R. (2015). The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War, revised edition. Toronto, ON: James Lorimer. ISBN 978-1-45940-872-2.

- Perkins, A. (2006). Baldwin. London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-90495-060-8.

- Petropoulos, J. (2006). Royals and the Reich: The Princes von Hessen in Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19979-607-6.

- Petropoulos, J. (2008). "The Hessens and the British Royals". In Urbach K. (ed.). Royal Kinship. Anglo-German Family Networks 1815–1918. Prinz-Albert-Forschungen/Prince Albert Research Publications. Vol. IV. Munich: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 147–160. ISBN 978-3-59844-123-3.

- Phillips, A. (2016). The King Who Had to Go: Edward VIII, Mrs Simpson and the Hidden Politics of the Abdication Crisis (electronic ed.). London: Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78590-157-7.

- Pope-Hennessy, J. (1959). Queen Mary: 1867–1953. London: G. Allen and Unwin. OCLC 905257338.

- Powell, T. (2018). King Edward VIII: An American Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19251-456-1.

- Roberts, A. (2000). The House of Windsor. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52022-803-0.

- Rose, Kenneth (1983). King George V. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-78245-2.

- Schwoerer, L. G. (1970). "Lord Halifax's Visit To Germany: November 1937". The Historian. 32: 353–375. OCLC 679014508.

- Sebba, A. (2013). That Woman: The Life of Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor (electronic ed.). New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-25002-218-9.

- Sereny, G. (2016). Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth. London: Picador. ISBN 978-0-33047-629-4.

- Sigmund, A. M. (2000). Women of the Third Reich. Richmond Hill, Ontario: NDE. ISBN 978-1-55321-105-1.

- Simpson, K. E. (2016). Soccer under the Swastika: Stories of Survival and Resistance during the Holocaust. London: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-44226-163-1.

- Smelser, R. (1988). Robert Ley: Hitler's Labor Leader. New York: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85496-161-0.

- Speer, A. (1970), Inside the Third Reich, New York: Macmillan, OCLC 869917120

- Strobl, G. (2000). The Germanic Isle: Nazi Perceptions of Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5217-8265-4.

- Taliaferro, J. W.; Ripsman, N. M.; Lobell, S. E. (2012). "Introduction: Grand Strategy Between the World Wars". In Lobell, S. E.; Taliaferro, J. W.; Ripsman, N. M. (eds.). The Challenge of Grand Strategy: The Great Powers and the Broken Balance between the World Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1 36. ISBN 978-1-13953-677-6.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1992). English History 1914–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19280-140-1.

- Time-Life (1990). The Center of the Web. The Third Reich. New York: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-6987-1.

- TNA (13 October 1937). "Windsor, Duke of: From Mr. Ogilvie-Forbes (to Mr. Harvey)". The National Archives. Kew. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Ullrich, V. (2016). Hitler: Ascent, 1889–1939. Vol. I. Translated by Chase, J. London: Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-285-4.

- ODNB (2004). "Windsor [née Warfield; Other Married Names Spencer, Simpson], (Bessie) Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (1896–1986), Wife of Edward, Duke of Windsor". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Unwin, B. (2010). Terrible Exile: The Last Days of Napoleon on St Helena (electronic ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-85771-733-7.

- Urbach, K. (2015). Go-betweens for Hitler. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19870-366-2.

- Vickers, H. (2011). Behind Closed Doors: The Tragic, Untold Story of the Duchess of Windsor. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09193-155-1.

- Vincent, J. (1984). "Appendix: The Duke of Windsor's Attempted Comeback, 1937". In Vincent J. (ed.). The Crawford Papers: The Journals of David Lindsay, Twenty-seventh Earl of Crawford and Tenth Earl of Balcarres (1871-1940), During the Years 1892 to 1940. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 616–621. ISBN 978-0-71900-948-8.

- Watt, G. (2017). "The Coronation Oath". Ecclesiastical Law Journal. 19: 325–341. OCLC 423735429.

- West, E. (2014). A Century of Royalty. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-74781-488-7.

- Williams, R. (2020). A Race with Love and Death: The Story of Richard Seaman. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-47117-936-5.

- Wilson, J. (2013). Hitler's Alpine Headquarters. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78303-004-0.

- Windsor, E. (1951). A King's Story: The Memoirs of H.R.H. the Duke of Windsor K.G. London: Cassell & Co. OCLC 776742761.

- Winter, G.; Kochman, W. (1990). Secrets of the Royals. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-86051-706-1.

- Wyllie, J. (2019). Nazi Wives: The Women at the Top of Hitler's Germany. Cheltenham: History Press. ISBN 978-0-75099-362-3.

- Ziegler, P. (1991). King Edward VIII: The Official Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-39457-730-2.