Montagu Norman, 1st Baron Norman

The Lord Norman | |

|---|---|

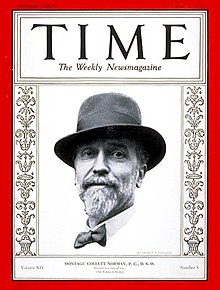

Norman on the cover of Time, 1929 | |

| Governor of the Bank of England | |

| In office 1920–1944 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Brien Cokayne |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Catto |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 1944 – 4 February 1950 Hereditary Peerage | |

| Preceded by | Peerage created |

| Succeeded by | None |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Montagu Collet Norman 6 September 1871 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 4 February 1950 (aged 78) Campden Hill, London, England |

| Spouse | |

| Profession | Banker |

Montagu Collet Norman, 1st Baron Norman DSO PC (6 September 1871 – 4 February 1950) was an English banker, best known for his role as the Governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944.

Norman led the bank during the toughest period in modern British economic history and was noted for his somewhat raffish character and arty appearance. A very influential figure, Norman, according to The Wall Street Journal, was referred to as "the currency dictator of Europe", a fact which he himself admitted to, before the Court of the Bank on 21 March 1930.[1] The economist and Court member John Maynard Keynes said of him: "Montagu Norman, always absolutely charming, always absolutely wrong".[2]

Early life and military service

[edit]Norman was the elder son of Frederick Norman and Lina Susan Penelope Collet, a daughter of Sir Mark Wilks Collet, 1st Baronet, himself a Bank of England Governor. The Norman family was well known in banking. Montagu's brother Ronald Collet Norman and his nephew Mark Norman became leading bankers. Montagu's great-nephew David Norman has also led a successful City career and is a noted benefactor of the arts. Montagu Norman was educated at Eton and spent one year at King's College, Cambridge.[3] He also joined the 4th Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire militia in 1894 and served in the Second Boer War. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1901.[4]

Merchant banking

[edit]After spending time in Europe, he joined Martins Bank in 1892; his father was a partner. In 1894 he joined Brown, Shipley & Co., where his maternal grandfather was a partner and, in 1895, Brown Bros. & Co. of New York. He became a partner at Brown Shipley in 1900 before leaving for South Africa. He retired from the bank in 1915.

Bank of England

[edit]He became a director of the Bank of England in 1907 and during World War I he was a financial advisor to government departments. He was appointed Deputy Governor in 1917 and he became Governor in 1920. He engineered the bank's takeover of the Anglo-Austrian Bank in Vienna and the creation of the Anglo-Czechoslovak Bank in Prague. Under Norman, the bank underwent significant change. He was a supporter of the return to the gold standard, which he called "knaveproof",[5] in 1925, despite the opposition of economist John Maynard Keynes.[6] In 1931, at the height of the Great Depression, Norman commented, "Unless dramatic measures are taken to save it, the capitalist system throughout the civilized world will be wrecked within a year";[7][8] he borrowed $250 million in an attempt to stave off speculative attacks upon the pound.[9] Later that year, however, the United Kingdom was forced to permanently abandon the gold standard after the publication of the May Report on the UK's budget deficit provoked a further financial crisis.[10] Norman was returning from a cruise to Canada at the time, and did not learn the news until he docked in the UK.[11]

Norman was a close friend of the German Central Bank President Hjalmar Schacht, who served in Hitler's government as President of the Reichsbank and Minister of Economics between 1934 and 1937. Norman was also so close to the Schacht family that he was godfather to one of Schacht's grandchildren.[12] Both were members of the Anglo-German Fellowship and the Bank for International Settlements.

While in the past Norman's role in the transferring of Czech gold to the Nazi regime in March 1939 was uncertain, careful investigation by historian David Blaazer into the Bank of England's internal memos has established that Norman knowingly authorized the transfer of Czech gold from Czechoslovakia's No. 2 account with the Bank for International Settlements to the No. 17 account, which Norman was aware was managed by the German Reichsbank. Within ten days the money had been transferred to other accounts. In the fall of 1939, two months after the outbreak of World War II, Norman again supported transfers of Czech gold to Hitler's Germany. On this occasion His Majesty's Government intervened to block Norman's initiative.[13] He retired from the bank in 1944.

Honours

[edit]Following his retirement, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Norman, of St Clere in the County of Kent, on 13 October 1944.[14] In addition to receiving the Distinguished Service Order, Norman was sworn of the Privy Council in 1923[15] and was created a Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown.[16]

Personal life

[edit]

On 2 November 1933, Norman married Priscilla Cecilia Maria Reyntiens, London councillor and granddaughter of Montagu Bertie, 7th Earl of Abingdon. He gained two stepsons from this marriage; Sir Simon Towneley and Sir Peregrine Worsthorne. Lord Norman & Cecilia had no children and on his death he passed the bulk of his estate to his nephew, Brigadier Hugh Norman.

In 1944, while visiting his brother on his country estate in Hertfordshire, Norman went for a walk and tripped over, causing an injury from which he never recovered. There is an amusing anecdote contained in Bill Bryson's book, that he tripped over a cow, but it is unclear where this anecdote came from as it is not known within his family.[17]

From 1904, Norman's London home was Thorpe Lodge, Airlie Gardens off Campden Hill in Kensington, which had been built c1816. Norman worked with Walter Knight Shirley and Ernest Gimson to modernise the house and redecorate it in the Arts and Crafts style. Lord Norman died at Thorpe Lodge in 1950 following a stroke. The house later became part of Holland Park School.[18]

During his married life, he lived at the Manor of St Clere in Kemsing, Kent, which he acquired from his uncle in 1935.[19]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Quigley, Carroll (1966). Tragedy & Hope. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 62. ISBN 0-945001-10-X.

- ^ Kynaston, David (1999). City of London, volume 3: Illusions of Gold 1914-1945. Chatto and Windus. p. 483.

- ^ "Norman, Montagu Collet (NRMN889MC)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "No. 27359". The London Gazette. 27 September 1901. p. 6326.

- ^ Nicholas Crafts, “Walking wounded: The British economy in the aftermath of World War I” dated 27 August 2014 at voxeu.org

- ^ Skidelsky, Robert (1992). John Maynard Keynes : the economist as saviour 1920-1937 : a biography. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-37138-0.

- ^ Howe, Quincy (1934). World Diary: 1929-34. New York. p. 111.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ahamed, Liaquat (19 March 2020). Lords of finance : 1929, the Great Depression, and the bankers who broke the world. Penguin Random House. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84794-300-2. OCLC 1179294023.

- ^ Ahamed, Liaquat (19 March 2020). Lords of finance : 1929, the Great Depression, and the bankers who broke the world. Penguin Random House. p. 424. ISBN 978-1-84794-300-2. OCLC 1179294023.

- ^ Ahamed, Liaquat (19 March 2020). Lords of finance : 1929, the Great Depression, and the bankers who broke the world. Penguin Random House. pp. 425–430. ISBN 978-1-84794-300-2. OCLC 1179294023.

- ^ Ahamed, Liaquat (19 March 2020). Lords of finance: 1929, the Great Depression, and the bankers who broke the world. Penguin Random House. p. 431. ISBN 978-1-84794-300-2. OCLC 1179294023.

- ^ Forbes, Neil (2000), Doing Business with the Nazis.

- ^ Blaazer, David (2005). "Finance and the End of Appeasement: The Bank of England, the National Government and the Czech Gold". Journal of Contemporary History. 40 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1177/0022009405049264. S2CID 197807556.

- ^ "No. 36746". The London Gazette. 13 October 1944. p. 4698.

- ^ "No. 32840". The London Gazette. 29 June 1923. p. 4605.

- ^ "No. 33260". The London Gazette. 25 March 1927. p. 1960.

- ^ Bryson, Bill (2013). One Summer. London: Transworld Publishers. p. 495. ISBN 9780385608282.

- ^ "The Phillimore estate - British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Cameron, Roderick (1981). Great Comp and its garden. London: Bachman and Turner Publications. pp. 131–144. ISBN 0859741001.

References

[edit]- Williamson, Philip (May 2006). "Norman, Montagu Collet, Baron Norman (1871–1950)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35252. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

[edit]- Ahamed, Liaquat, Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, Penguin Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59420-182-0

- Boyle, Andrew, Montagu Norman. A Biography, Cassell, 1967.

- Hargrave, John, Professor Skinner alias Montagu Norman, Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., [pub. 1939].

External links

[edit]- 1871 births

- 1950 deaths

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment officers

- British Army personnel of the Second Boer War

- British anti-communists

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- Deputy governors of the Bank of England

- English bankers

- English Nazi collaborators

- Governors of the Bank of England

- Grand Officers of the Order of the Crown (Belgium)

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- People educated at Eton College

- People from Kemsing

- People from Kensington

- Barons created by George VI

- Military personnel from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea